By Eric Holscher

Treating documentation as code is becoming a major theme in the software industry. This is coming from both developers, who are starting to treat documentation as a priority alongside tests and code, and writers, who are seeing a lot of value in integrating more into the development process. This marriage of cultures isn’t simple, but having the proper tools for the job makes both sides happy with process and results.

A lot of developer tools don’t work well for writers. Sphinx and Read the Docs are unique in this ecosystem in that they have powerful features that both writers and developers want in one convenient package.

Overview of the Ecosystem

Read the Docs is the largest open source documentation hosting site in the world. Open source in this context means that the code is open source and the documentation hosted is for open source software. It is a developer-focused platform, but it has most of the features that technical writers have come to expect in a tool as well. This blending of worlds makes it the best-suited platform for teams that want both writers and developers contributing to product and API documentation.

Read the Docs is best thought of as a continuous documentation platform for Sphinx. Continuous documentation is analogous to continuous integration of code, which runs the tests on each commit. In practice, this means that your documentation is built, tested, and updated on every commit.

Sphinx provides a documentation generator that is best-in-class for software docs. Sphinx documents are written in the reStructuredText markup language. reStructuredText is similar to Markdown, but much more powerful, as you’ll see in this article. Read the Docs provides a hosting platform for Sphinx, running a build on each commit of your repository.

As a writer who uses Sphinx, you write reStructuredText in plain text files. You then build your documentation by running Sphinx on the command line. Generally it’s easiest to output HTML for local writing and testing, and then you can let Read the Docs generate PDFs and other formats.

This article provides an overview of the features of Sphinx and Read the Docs, and enables you to evaluate them for use in your organization.

Introduction to Sphinx

Sphinx (www.sphinx-doc.org) is the documentation tool of choice for the Python language community, and increasingly also for other programming languages and tools. It was originally created in 2008 to document the Python language itself.

Over the past eight years, it has turned into a robust and mature solution for software documentation. It includes a number of features that writers expect, such as:

Single Source Publishing

- Output to HTML, PDF, ePub, and more

- Content reuse through includes

- Conditional includes based on content type and tags

- Multiple mature HTML themes that provide great user experience on mobile and desktop

- Referencing across pages, documents, and projects

- Index and Glossary support

- Internationalization support

It also has practical and powerful tools for documenting software specifically, including:

- Semantic referencing of software concepts, including classes, functions, programs, variables, etc.

- Including code comments in documentation output for many programming languages

- Tools for documenting HTTP APIs

- Extensions with the Python language

- A vast array of third-party extensions providing powerful new roles and directives

This article isn’t enough to cover all of the power packed into this tool. But I hope to pique reader interest so that you can try these tools out and research their capacity for yourself.

Using Sphinx

reStructuredText is a powerful language primarily because the syntax can be extended. reStructuredText supports two types of extension:

- Paragraph level (with Directives)

- Inline level (with Interpreted Text Roles, or roles for short)

Paragraph Level Markup

Let’s see a basic example of a Directive in reStructuredText:

.. warning:: Here be dragons! This topic covers a number of options that might alter your database.

Proceed with caution!

.. figure:: screenshot-control-panel.jpg

:width: 50%

An overview of the admin control panel.

Here warning acts as the name of the directive, and is the part you can extend for custom directives. In the figure, screenshot-control-panel.jpg is an argument, :width: is an option, and the rest is the content. They enable customization of directives, and show the full power of reStructuredText. You’ll notice that Sphinx uses whitespace to denote where a directive ends. The “Proceed with caution!” is still part of the warning, and everything that continues to be indented will be part of that warning.

Sphinx ships with a number of powerful directives for documenting code. You can also write your own if you have someone on your team that knows Python.

Inline Markup

For extensibility inside of a paragraph, Sphinx uses roles. Here is an example:

You can learn more about this in 1984. It is implemented in our code at System.Security

Here you can see rfc and class act as the name of the role, and then you can pass in a single argument. For the rfc role, it generates a link to the online reference for RFC 1984 with a text of RFC 1984.

The class role is where things get interesting. This acts as a reference to the class System.Security that is documented in your project, which is a hyperlink in the HTML output, but also a working link in PDF and other outputs.

You can implement your own roles with Python. This enables you to create powerful semantic constructs inside the actual markup you’re using to write documentation. If you worked building software at a toy factory, you could create a custom semantic sytnax for our own software:

Check out :jira:`199` for information on the :toy:`jump-rope`.

There is a fix in our :unit-test:`assert-jump-rope-length`.

These custom roles work in your .rst files, but also in any kind content that is pulled out of a comment in your source code, too.

Let’s see how to take these sets of reStructuredText files and turn them into a document set.

Table of Contents (TOC) Tree

Sphinx lets you combine multiple pages into a cohesive hierarchy. The toctree directive is a fundamental part of this structure.

.. toctree::

:maxdepth: 2

install

support

The above example outputs a Table of Contents in the page where it occurs. The maxdepth argument tells Sphinx to include two levels of headers. This also tells Sphinx that the other pages are subpages of the current page, creating a “tree” structure of the pages:

index

├── install

├── support

The TOC Tree is also used for generating the global navigation inside of Sphinx. The index at the top of your project acts as the root of the navigation. The toctree is quite important and one of the most powerful concepts in Sphinx. More info on the toctree can be found online http://www.sphinx-doc.org/en/stable/markup/toctree.html.

Working with Code

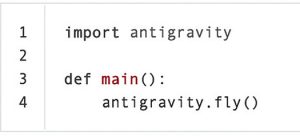

Showing code examples is a common task in all documentation. Sphinx is quite well prepared for this task. Let’s see how we can show a basic code example:

.. code-block:: python

:linenos:

import antigravity

def main():

antigravity.fly()

This markup displays the Python snippet with syntax highlighting and line numbers. The python in the above example is an argument to the code-block directive. The :linesnos: is an option that says to display line numbers for the code block. In the HTML output, it would look like this:

Sphinx doesn’t stop there though. It allows you to store your code examples in external files and be included in your documentation for easier maintenance. This uses the literalinclude directive:

.. literalinclude:: example.rb

:language: ruby

:emphasize-lines: 12,15-18

The neat addition here is the :emphasize-lines:. This shows the lines highlighted in your output. This is quite useful for showing sets of code examples where a subset of the code changes. You can also specify just a subset of lines to show with the :lines: option, so you don’t have to manage multiple snippets.

There’s far more power to Sphinx directives than this article can show. You can see the full documentation for them on the Sphinx website, http://www.sphinx-doc.org/en/stable/markup/code.html.

Working with References

A powerful reference system is a large part of the power of Sphinx. You are able to reference arbitrary headings and paragraphs in your content, but also semantically reference a large number of programming concepts as well. On top of that, Sphinx includes intersphinx which allows referencing across Sphinx projects. This means that if you have multiple projects inside your company, you can still use semantic referencing across them!

A simple reference is defined like this:

.. _reference-target-name::

This is a bit of content.

This is how you point to the above reference, :ref:`reference-target-name`

Sphinx also includes a number of other semantic reference types. Examples of other semantic reference types that Sphinx provides:

- :doc: for referencing documents

- :cls: for referencing programming classes

- :term: for referencing glossary terms

All references support intersphinx, which allows you to prefix your references with a specific project name. So if your user guide needs to reference your API documentation, you could write, Check out the :cls:`api-ref:api.request` which would know to look in your api-ref project for the class. The name api-ref is arbitrary, and is defined in your project configuration’s intersphinx_mapping.

You can see the complete set of references in the Sphinx documentation:

- Cross Referencing Syntax—www.sphinx-doc.org/en/stable/markup/inline.html#cross-referencing-syntax

- Intersphinx—www.sphinx-doc.org/en/stable/ext/intersphinx.html

Including Comments from Source Code

Integration with code is one of the largest benefits of Sphinx. You can easily embed software comments from multiple languages, including Python, Java, and .NET.

Here is an example of embedding Python documentation for a class in your project:

Make a request

--------------

You can make requests using the :func:`api.request` module.

It makes HTTP requests against our website.

Here is the basic function signature:

.. autofunction:: api.request

As you can see, you can include generated content in the file that you’re writing by hand. This allows for building a narrative around generated code comments, instead of giving your users a separate User Guide and API Reference, which is often times just a alphabetical listing of code.

Documentation is best written by humans. Pulling comments from source code is valuable, but it should be a small part of a proper set of documentation. You can read more about including code comments in the following documentation pages:

- Domains, where the references are defined—www.sphinx-doc.org/en/stable/domains.html#what-is-a-domain

- Autodoc, which generates docs from Python code—www.sphinx-doc.org/en/stable/ext/autodoc.html

- Breathe, which bridges doxygen and Sphinx—https://breathe.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

- AutoAPI, which bridges .NET and Sphinx—https://sphinx-autoapi.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

Tables

Working with tables can be the bane of anyone who uses plaintext markup languages. Most other languages require that you write them in the file with some arcane syntax. However with reStructuredText, you can use directives to make this much easier.

You can use either of two powerful list directives, csv-table and list-table. Here is an example of csv-table:

.. csv-table:: Frozen Delights!

:header: “Treat”, “Quantity”, “Description”

:widths: 15, 10, 30

“Albatross”, 2.99, “On a stick!”

“Popcorn”, 1.99, “Straight from the oven”

This shows the inline markup, however the CSV can also be managed in an external file. This allows you to manage your complex tables in a third-party tool and have your documentation consume them from a CSV, which is a much nicer workflow.

Internationalization

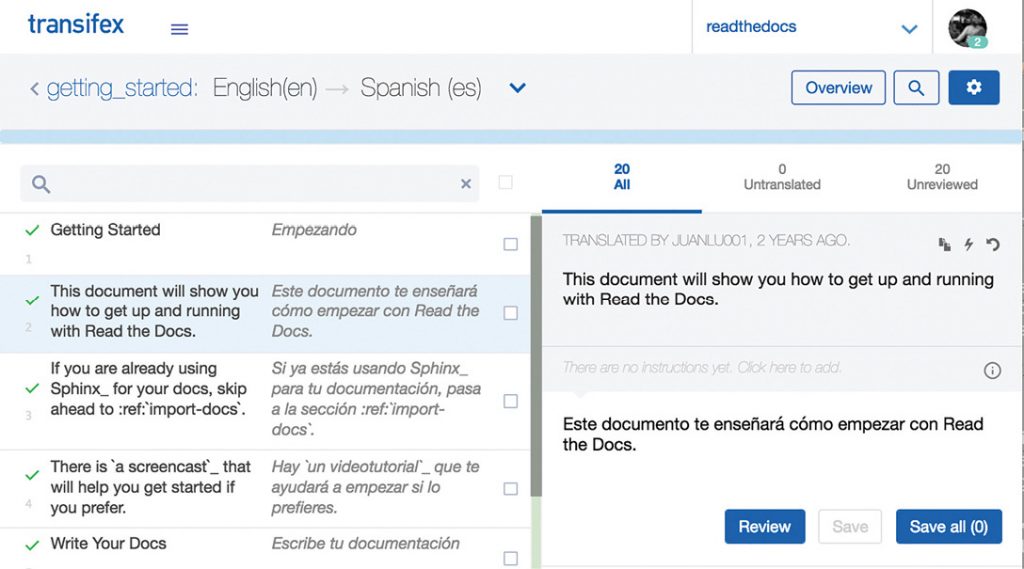

Sphinx includes support for translating documentation into multiple languages. Since Sphinx knows the structure of your documents, it is able to generate translatable strings split by each paragraph, heading, or figure.

Sphinx internationalization works using the gettext system. It ships with a builder that allows you to generate a catalog:

make gettext

You can then use that catalog as the base translation, using any tool that supports gettext. I recommend using Transifex, which gives you a Web-based system for translating the documentation (see Figure 1).

You can then tell Sphinx what language to generate for its documentation when you build it by setting the language setting. Read the Docs also supports internationalization, allowing you to host multiple languages of your project documentation.

More information on Sphinx internationalization can be found online at www.sphinx-doc.org/en/stable/intl.html and http://docs.readthedocs.io/en/latest/localization.html.

My Blog

Sphinx is quite versatile, which means you can use it for a lot of different use cases. I use a package called ablog for hosting of my blog over at http://ericholscher.com.

The most basic usage allows you to specify that a document is a blog post with the post directive:

.. post:: 2016-03-15 09:00

:tags: writing, stc, sphinx

The post directive adds the document to the set of posts. You can show a post listing by using the postlist directive:

.. postlist::

:tags: stc

This shows some of the magical things you can do with Sphinx’s extensibility. If you’re curious, this article was written in reStructuredText and then exported to Word for publishing. You can see the full source online at https://github.com/ericholscher/ericholscher.com/blob/master/site/blog/2016/jul/1/sphinx-and-rtd-for-writers.rst.

Custom Builders

Sphinx supports custom builders to perform tasks beyond providing basic output formats. Some examples that ship with Sphinx:

- A linkcheck builder that tells you about broken URLs

- A builder that outputs all the changes in the latest version of your code for a changelog

- An XML builder that outputs a representation of your documents in XML

- A Man page builder that builds man pages from your documentation

- JSON builder that outputs your pages as HTML inside of JSON, with some metadata, for embedding dynamically

You can get as creative as you like with custom builders, which is another place to extend Sphinx outside of the markup.

Tradeoffs with Sphinx

Every tool has its issues and limitations. I’d like to address some of the issues with Sphinx, so that you can go into it with eyes wide open.

The biggest issue is that it is originally a programmer tool. This means that a lot of the designs assume knowledge of code, especially for installation and extending the tools. Knowledge of the command line is definitely required.

The markup language, reStructuredText, is also a bit finicky. It depends on whitespace for separation of content, which is a natural concept for Python programmers, but not for most writers.

In general, though, a lot of the complexity in the language comes from the extensibility and power. When compared to something like Markdown, reStructuredText can do so much more that it’s worth the complexity and somewhat steep learning curve.

Introduction to Read the Docs

Read the Docs is a hosting platform for Sphinx-generated documentation. It takes the power of Sphinx and adds version control, full-text search, and other useful features. It pulls down code and doc files from Git, Mercurial, or Subversion, then builds and hosts your documentation. We’ll use GitHub in this example as it’s the most commonly used system for accessing code.

To get started, you create a Read the Docs account, and link your GitHub account. Then you select the GitHub repository you’d like to build documentation for, at which point the magic happens.

Read the Docs will:

- Clone your repository

- Build HTML, PDF, and ePub versions of your documentation from your master branch.

- Index your documentation to allow full text search

- Create version objects from each tag and branch in your repository, allowing you to optionally host those as well

- Activate a webhook on your repository, so when you push code to any branch, your documentation is rebuilt

Whenever you commit new code or documentation to your repository, your documentation is kept up to date. This works with your master branch, as well as any other branches or tags you might have activated documentation for.

Read the Docs has two special versions:

- latest which maps to the most up-to-date development version of your software

- stable which maps to the latest tagged release of your software

These are version aliases that help maintain stable URLs for the most up-to-date commits or for the most stable released version of your software.

We built Read the Docs to be “set it and forget it.” Once you set your project up and activate the versions you want hosted, we sit downstream of your version control system and just keep your documentation up to date. It feels pretty magical once it’s set up, and it takes the thankless task of deploying documentation out of your day.

Recommended Versioning System

Read the Docs only works with version control. This means that however you version your software, your documentation follows suit. This is great for integrating with your development team, but it also means you need to think about the proper strategy for versioning.

After working with a lot of open source projects, we generally recommend this workflow for projects:

- A master branch that the next release of your software is developed on

- Git branches for ongoing maintenance of each version of your software that is maintained

- Git tags for specific released versions that users might be using

We recommend release branches because it allows you to update them over time. Git tags are static, so they are appropriate for specific versions that a user might have installed. An example:

- master is your 2.2 release that isn’t out yet

- 2.1.X is your release branch for the 2.1 version

- 2.1.1 is a similar tag of your 2.1 branch, with the latest release

- 2.1.0 is the first tag of your 2.1 branch

Additional Read the Docs Features

Read the Docs also provides the following features:

- GitHub, Bitbucket, and Gitlab webhooks

- Custom domain hosting

- Full-text search for all your projects’ versions

- Status badges to show your docs are up to date

- Hosting of multiple languages for a specific project

- Hosting of multiple projects on a single domain with “subprojects”

Feel free to email me or find me at a conference if you want to talk more about these concepts, or if you have ideas for other neat features.

Real Life Examples

Read the Docs has a large number of users across many different programming languages. This is in part because Sphinx is such a powerful and dynamic tool, and Read the Docs makes it easy and free to host docs for your open source project.

Here are some examples that show the wide range of projects using Sphinx and Read the Docs:

- ASP.NET—Microsoft’s Web framework, https://docs.asp.net

- Julia—A language for scientific computing, http://docs.julialang.org

- Jupyter—An interactive programming environment, http://jupyter.readthedocs.io

- PHPMyAdmin—A Web-based database editor, https://docs.phpmyadmin.net

- Write the Docs—The community site for Write the Docs, www.writethedocs.org

As you can see, a wide range of projects are using the tools for many different uses. It’s a powerful tool for writing prose as well as documenting source code.

Going Forward

Sphinx is an incredibly powerful tool. Read the Docs builds on top to provide hosting for Sphinx documentation that keeps your docs up to date across versions. Together, they are a wonderful set of tools that developers and technical writers both enjoy using.

I firmly believe that the more integrated with the product development process technical writers get, the better our products get. Tools that integrate documentation and development workflows make it much easier for writers to become part of the larger development process. Sphinx and Read the Docs have been battle tested by hundreds of thousands of open source developers for years, and are a great choice for your software documentation project.

ERIC HOLSCHER (eric.holscher@gmail.com)is the co-founder of Read the Docs and a co-organizer of the Write the Docs conference. Along with community organizing and open source work, he does consulting around software documentation and speaks at a number of industry events each year. When he isn’t expressing his views on software docs, he’s getting views from the top of mountains.