By Tony Self

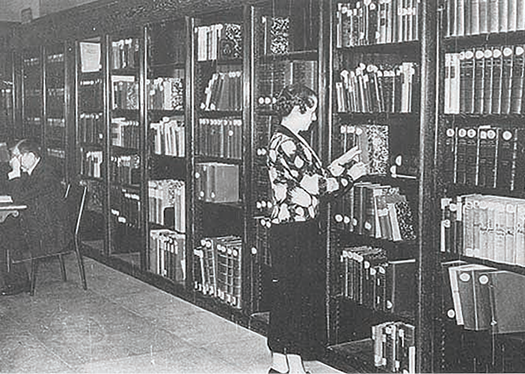

She was a very influential figure in the field of documentation, yet most of today’s information and content professionals have never heard of her. She strongly and successfully argued for specialized education for documentation professionals, and earned the nickname “Madame Documentation.” This illusive figure in the history of documentation has been “hiding in plain sight” for over half a century. Her name was Suzanne Briet.

Why haven’t we heard of her? Or, more precisely, why isn’t the name Briet familiar to today’s technical communicators and “documentalists” in the English-speaking world? Most likely for two reasons: she was French, and she lived from 1894 to 1989.

Suzanne Briet’s most famous contribution to information science was the efficient slim book, Qu’est-ce que la documentation? (What Is Documentation?), published in 1951. In the 48 pages of the book, she set about defining and re-defining the nature of documents and documentation. The record of events and opinions and discoveries, and life, were no longer books and albums, but snapshots and pages and sounds and images. To catalogue and organize and understand and manage this information, the specialization of documentation was needed, building upon and extending the skills of librarians and bibliographers. “What words fail to communicate, image and sound try to deliver to all. Documentation, thus understood, is a powerful means for the collectivization of knowledge and ideas,” she wrote. She predicted in the 1950s that libraries would be replaced by “documentation centers,” and that such centers in business organizations would produce documents on demand, spontaneously delivered, and personalized.

Mme Briet passed away at the impressive age of 95 in 1989 and is not available to interview. However, we can perhaps imagine what an interview with her might have been by drawing on her own words from “What Is Documentation?”

Tony: Good evening, Mme Briet. Can we start by asking about the term “documentalist” which you coined. What is a documentalist?

Mme Briet: The documentalist is a person who performs the craft of documentation. He must possess the techniques, methods, and tools of documentation.

Tony: What skills does a documentalist need?

Mme Briet:

- a specialist of the matter concerned, that is to say, that he possesses a cultural specialization related to that of the institution where he is employed;

- understands the techniques of the form of documents and their treatment (choice, conservation, selection, reproduction);

- respects the documents in their physical and intellectual integrity;

- is capable of proceeding to a valuable interpretation and selection of the documents which he is responsible for, in view of their distribution or documentary synthesis.

Tony: And what is documentation?

Mme Briet: What words fail to communicate, image and sound try to deliver to all. Documentation, thus understood, is a powerful means for the collectivization of knowledge and ideas.

Tony: You use the discovery of an antelope as a way of defining documents, and that very much broke away from the previous idea of documentation being something that had to be contained in a book or folder. Can you explain “Briet’s Antelope” for us?

Mme Briet: An antelope of a new kind has been encountered in Africa by an explorer who has succeeded in capturing an individual that is then brought back to Europe for our Botanical Garden. A press release makes the event known by newspaper, by radio, and by newsreels. The discovery becomes the topic of an announcement at the Academy of Sciences. A professor of the Museum discusses it in his courses. The living animal is placed in a cage and cataloged. Once it is dead, it will be stuffed and preserved (in the Museum). It is loaned to an Exposition. It is played on a soundtrack at the cinema. Its voice is recorded on a disk. The first monograph serves to establish part of a treatise with plates, then a special encyclopedia (zoological), then a general encyclopedia. The works are cataloged in a library, after having been announced at publication. The documents are recopied (drawings, watercolors, paintings, statues, photos, films, microfilms), then selected, analyzed, described, translated (documentary productions). The documents that relate to this event are the object of a scientific classifying (fauna) and of an ideological classification. Their ultimate conservation and utilization are determined by some general techniques and by methods that apply to all documents. The cataloged antelope is an initial document and the other documents are secondary or derived.

Tony: In your time “technology” looked a lot different, but would you say that a documentalist required a lot of technical knowledge?

Mme Briet: The documentalist is a specialized technician, whose professional knowledge will be increasingly technical in the future. The documentalist will be more and more dependent upon tools whose technicality increases with great rapidity.

Tony: You have said that one of the problems of documentation is the book-centric mindset. We people of the 21st century think this is a new phenomenon, brought about by online documents, topic-based Web sites, social media, and search engines. Why was this book-centered approach a problem in your century?

Mme Briet: For the past few centuries, the book has remained the bibliographic entity. Autographs were grouped within books. Engravings were preserved within albums. Periodicals were bound in volumes. Today, books have a tendency to become scattered in loose leaves. The book accompanies the scholar’s notepad. The publishing business reconsiders its methods for best responding to the demand of the century. For some decades, the fact, information, the periodical text, the illustration have been isolated from their contexts: pulled from the book, the daily paper, the periodical, the official newspaper, and given a place in binders. By an inverse evolution of the card catalog, which schematizes and brings together descriptions of documents, the construction of such binders tends to present the documents themselves, assembling them for ease of consultation. This happens in the majority of cases with graphic documents. It is nevertheless possible to find in binders an example, a specimen, of a given matter.

Tony: What qualifications and skills do you think documentalists should have?

Mme Briet:

- Higher education and cultural or professional specialization

- Technique of document use and production

- Technique of document handling

Tony: Translation and localization is a big part of the documentation business. Some say this is brought about by globalization, better and cheaper trade, and multinational corporations. As a Francophone, and someone living in 1950s post-war Europe, what are your views on translation and localization?

Mme Briet: The principal obstacle to unification lies in the multiplicity of languages, in the babelism that stands in opposition to both understanding and cooperation. One almost no longer seeks to substitute an artificial language for natural ones. Esperanto isn’t progressing. On the contrary, the major languages, that is to say, English, French, and Spanish, tend to spread so as to become the indispensable interpreters of civilized people. German has retreated. Russian is not yet in the forefront. The Orientals always speak their language and another language. The world divides itself into linguistic areas. The organization of documentary work must, take account of this reality. In regard to the creation of cataloging rules, book selection, translations, and analyses, the distribution of documents on the planet will adapt to this necessity. The recording of linguistic phenomena is not of any less importance than the recording of illiteracy statistics

We must distinguish two tendencies at play today. On the one hand, knowledge of foreign languages allows a much larger diffusion of written works than previously, and gives to worldwide readership an audience that can only increase. One thinks of the innumerable translations of the Bible, Victor Hugo, Marx, and Duhamel. On the other hand, the scientific work of documentation tends to content itself with a few base languages for reasons of economy. The scientific translation ought to be organized with as much care as the literary translation. While individually, one seeks direct contact with, or multiple translations of, literary monuments of every country and of all times, collectively, the technique of document distribution will be content with three or four languages, maximum.

Tony: Social media is making inroads into the modern documentation profession, and ideas such as collaborative authoring and peer-generated content are being used. Is technological progression in documentation a new thing?

Mme Briet: The time is past—it was 1931—when an English librarian said at an international conference that if he would mention documentation in his country he would be asked what this new disease might be. The words, doctrines, techniques, and tools have forged a path. Theory and practice have kept pace. The new profession has become more and more technical: learned on the one hand, manual on the other. “What a manual century!” Rimbaud said, speaking of his own, nineteenth, century. While culture was being democratized, technology was making gigantic progress. The means of expression multiplied while expanding their range in space and time. Expositions and congresses thwarted the tendency of all specializations, just as all frontiers, to withdraw within themselves. The appreciation of human unity has been growing on cultural, political, social, and religious fronts. Documentation-technique, the documentation-profession, and the documentation-institution are not enough to address all the needs of the growing society. They are, nonetheless, essential mechanisms that must, henceforth, be reckoned with.

Tony: Thank you for your time and your contributions to the profession.

Renée-Marie-Hélène-Suzanne Briet retired from the profession in 1954, not long after Qu’est-ce que la documentation? was published. She spent her retirement writing essays and books about a number of subjects, including the history of her birthplace (the Ardennes region of France), and its other famous citizen, the Symbolist poet Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud. She died in Paris in 1989 with over 100 books, essays, and other publications to her name.

Renée-Marie-Hélène-Suzanne Briet retired from the profession in 1954, not long after Qu’est-ce que la documentation? was published. She spent her retirement writing essays and books about a number of subjects, including the history of her birthplace (the Ardennes region of France), and its other famous citizen, the Symbolist poet Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud. She died in Paris in 1989 with over 100 books, essays, and other publications to her name.

All the “imagined interview” answers are directly from Madame Briet’s book What is Documentation?: English Translation of the Classic French Text by Suzanne Briet, translated by Ronald E. Day, Laurent Martinet, and Hermina G. B. Anghelescu.

Required Reading

Briet, Suzanne. 2006. What is Documentation? English Translation of the Classic French Text (Lanham, Maryland: ScarecrowPress), translated by Ronald E. Day, Laurent Martinet, and Hermina G. B. Anghelescu.

Maack, Mary Niles. “The Lady and the Antelope: Suzanne Briet’s Contribution to the French documentation Movement, Accessed 24 Aug 2016 from https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/maack/BrietPrePress.htm.

TONY SELF has worked as a technical communicator in Australia and New Zealand for over 30 years, specializing in online help systems, computer-based training, and hypertext documents. In 1993, Tony founded HyperWrite, which offers consultancy services in online and Internet strategy, innovative solutions and specialized training. In addition to his consulting work, Tony is an Adjunct Teaching Fellow at Swinburne University of Technology. He is a Fellow of the Institute of Scientific and Technical Communication and holds a PhD in semantic mark-up languages, a Graduate Diploma in Technical Communication, and a Graduate Certificate in Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. He is the author of “The DITA Style Guide.”

TONY SELF has worked as a technical communicator in Australia and New Zealand for over 30 years, specializing in online help systems, computer-based training, and hypertext documents. In 1993, Tony founded HyperWrite, which offers consultancy services in online and Internet strategy, innovative solutions and specialized training. In addition to his consulting work, Tony is an Adjunct Teaching Fellow at Swinburne University of Technology. He is a Fellow of the Institute of Scientific and Technical Communication and holds a PhD in semantic mark-up languages, a Graduate Diploma in Technical Communication, and a Graduate Certificate in Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. He is the author of “The DITA Style Guide.”

This method which Tony Self used to create this imagined conversation is clever. I enjoyed reading it. Given that All the “imagined interview” answers were taken directly from Madame Briet’s book What is Documentation?, it is a compelling construction.