By Tiffany Price

The Western educational system is growing in terms of international student representation, and as the world globalizes in this respect, there is an expected continuous progression of internationals integrating into the Western classroom. As the Western classroom shifts in international representation, instructors are called to adjust with this change. One measure of transitioning that is deemed necessary in an intercultural classroom requires pedagogical adjustments in order to meet the educational needs of all students in the classroom.

Through the investigation of an assimilationist approach, the instructor of a university-level intercultural classroom will discover how not to proceed when it comes to creating a welcoming learning environment for international students. The assimilationist approach, which this article will spend time dissecting and debunking, is counterproductive to the positive temperature of the Western classroom as it grows in international representation. With an assimilationist approach firmly positioned in the instructor’s pedagogy, the international student is expected to adopt responsibility instead of leaving the responsibility for class involvement in the instructor’s hands. Also, an assimilationist approach to an intercultural classroom leaves little to no room for pedagogical adjustments necessary for creating a warm and welcoming environment for all students, domestic and international.

Assimilationist Approach

An assimilationist approach to an intercultural classroom suggests that students with an international background must assume the burden necessary to learn in a culturally unfamiliar environment (Macdonald & Sundararajan). However, international students integrating into a Western educational system will not come prepared with the knowledge of cultural norms and behaviors that will allow for simple adaption. In fact, Ulijn and St.Amant make a strong claim for the cultural differences that vary from country to country, and that any student introduced to the Western educational system would struggle to simply adapt without assistance from the instructor.

The history of an assimilationist approach, derived from an immigration movement, dates back to the early 19th century. The concept of assimilation, examined by Brown and Bean, explains that “In general, classic assimilation theory sees immigrant/ethnic and majority groups following a ‘straight-line’ convergence, becoming more similar over time in norms, values, behaviors, and characteristics.” The history of immigration, where the assimilationist approach is encouraged, assumes that those immigrants are permanently transitioning to the Western culture and intend to remain in or assimilate to that culture. The international student would likely be staying in the Western culture for the duration of their educational endeavors. Therefore, to expect an international student to adopt an assimilationist approach in an intercultural classroom without assistance from the university instructor would be counterproductive to what both the instructor and the student should strive for in terms of achieving student success in the classroom.

The counterproductive assumption that international students will be prepared to assimilate into the Western educational system without assistance proves that the assimilationist approach applied to an intercultural classroom will create disharmony between students and instructors. Furthermore, the repercussions of applying an assimilationist approach to the intercultural classroom could entail that the international student representation in the Western educational system would decline due to the uncomfortable assumption of international student assimilation adopted by the instructor (Macdonald & Sundararajan).

Instructor Responsibility

An assimilationist approach to an intercultural classroom also entails that the students will be responsible for their complete understanding of all classroom material and activities, which takes the responsibility out of the instructor’s hands. Getto was introduced to a culturally diverse classroom where he adopted the idea for participatory design as a means of encouraging student participation in classroom activities/lessons. This drive to encourage student participation led Getto to pursue personal interaction with all students in the classroom with the intention to improve his instructional methods and achieve student success in the classroom. Getto used questionnaires and interviews in his study, which led to concrete evidence supporting the fact that instructors are required to be proactive in order to get all students, international and domestic, interacting with the classroom material, discussions, and activities.

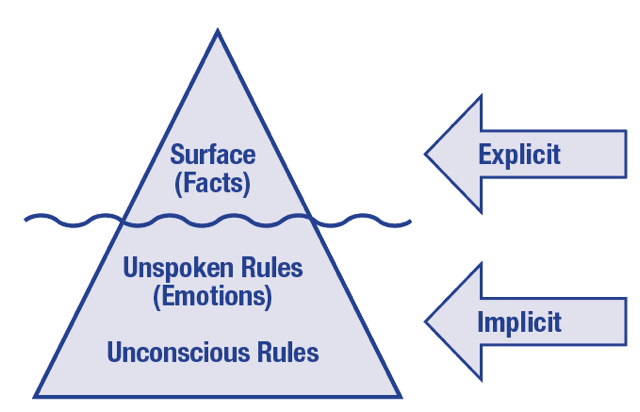

The need to break the mold of an assimilationist approach is evidenced through the discovery of different cultural norms that vary from country to country. Figure 1 provides the “iceberg model” used in Ulijn and St.Amant’s study as a means of depicting cultural differences and providing an analogy for human consciousness. When attempting to comprehend how culture effects communication, there are levels of explicit and implicit complexities within each culture that should be examined.

The explicit and implicit complexities would dismantle the assimilationist approach as we see how people from opposing cultures behave and respond to communication opportunities on and below the surface. Figure 1 describes explicit complexities to cultural norm as those facts visible on a surface level. In an educational environment, this would entail that the international students are stretching their educational experience by pursuing a Western venue rather than enrolling in a university that adheres to their comfort level and cultural norms.

Furthermore, Figure 1 also reveals implicit complexities to cultural norms. This implicit information exists below the surface; what we cannot attest to on a visual level. So, this implicit section would involve behaviors, rules, emotions, norms, and traditions specific to any country or culture (Ulijn & St.Amant). Examining Figure 1 debunks the myth that adopting an assimilationist approach in an intercultural classroom is an appropriate response on the instructor’s behalf when looking to achieve student success in an intercultural classroom.

Instructor Pedagogy Adjustment

In an intercultural classroom, international and domestic students have specific needs that vary from culture to culture; needs that, if met by the university instructor, would allow for student success. The instructor is responsible for examining the various needs of the classroom in order to create a warm and welcoming environment for all students to achieve success—and the means of doing so lie directly in pedagogy adjustment. Macdonald and Sundararajan claim that students from an international background will likely have difficulty being active in classroom discussion. This is commonly due to the fact that “international students’ efforts to participate in the classroom are thwarted by the pace of the discussion and the speed of domestic students’ speech” (51). This means that instructors are required to examine their pedagogical approach to an intercultural classroom and determine important measures of inclusion that divorce themselves from an assimilationist approach. Class discussion is just one of many examples that require pedagogical adjustments in an intercultural classroom where domestic and international student success is the goal.

Conclusion

The negative connotations that follow the description of an assimilationist approach in an intercultural classroom will disrupt the temperatures of warmth and inclusion necessary for student achievement in a Western university context. An assimilation approach assumes that students will adopt the norms of Western culture as a way of integrating into the educational system, and this approach takes the responsibility for inclusion strategy out of the instructors’ hands (Macdonald & Sundararajan). Such counterproductive assumptions do not calculate that the opposing cultural norms will make international student assimilation very difficult on the international student, potentially ruining their experience in a Western educational system.

Therefore, the need for adjusted instructor pedagogies when dealing with an intercultural classroom to ensure that all students are engaging with classroom material, discussions, and activities is essential if an instructor wants to create a welcoming environment that will allow for student success. Overall, instructors of an intercultural classroom need to drop all adopted theories surrounding an assimilationist approach to education. Instead, university instructors of an intercultural classroom need to adjust pedagogies in ways that will achieve international and domestic student success in the classroom.

References

Brown, S. K., and F. D. Bean. Assimilation Models, Old and New: Explaining a Longterm Process. The Online Journal of the Migration Policy Institute. 2006. Retrieved from www.migrationpolicy.org/article/assimilation-models-old-and-new-explaining-long-term-process.

Getto, G. 2014. Design for Engagement: Intercultural Communication and/as Participatory Design. Rhetoric, Professional Communication and Globalization 5.1 (2014): 44–66.

Macdonald, L. R., and B. Sundararajan. Understanding International and Domestic Student Expectations of Peers, Faculty, and University: Implications for Professional Communication. Rhetoric, Professional Communication and Globalization 8.1 (2015): 40–56.

Ulijn, J. M., and K. St.Amant. Mutual Intercultural Perception: How Does It Affect Technical Communication?—Some Data from China, the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Italy. Technical Communication 47.2 (May 2000): 220–237.

TIFFANY PRICE is celebrating her fourth term of teaching English Composition 1 through University of the People, a strictly online university that has recently partnered with UC Berkeley. Tiffany is able to apply her focus on the intercultural classroom, developed through her graduate studies in Technical and Professional Communications at East Carolina University, as she teaches students in an online environment that extends to over 200 different countries. In unison with attaining a certificate in Professional Communication through East Carolina University, Tiffany also achieved a certificate in Multicultural and Transnational Literatures. Tiffany and her husband have just recently settled in Ann Arbor, Michigan after a two-year residency in Manchester, England.