By Valerie Vogel and Joanna Grama

We often think of information security as a technology discipline with technological solutions implemented by technical experts. This first line of technical defense is backed up by policies and processes telling end users what should, or more often shouldn’t, be done to help protect the organization. Logically, this makes sense because cybersecurity is generally broken down into three essential components: people, processes, and technology. However, an organization’s information security program is not just about firewalls, phishing users, and acceptable use policies. Over the past several years there has been a shift in how we approach information security more strategically by focusing on the people and human risks.

Farewell FUD and the Weakest Link

This change has been a long time in the making. Information security is fundamentally about stopping bad things from happening or reducing their impact when those bad things do happen. As a result, information security professionals have often been accused of relying on fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD) to implement information security controls and safeguards and to advance the missions of information security. Using FUD to make a business case for information security relies on a psychological response, even in an organization, to avoid the fear-triggering event. It’s a pessimistic tactic that is more likely to be denounced as the profession continues to mature.

The profession has also used a similarly pejorative tactic when referring to end-users as the weakest links in protecting an organization’s information security posture. The term refers to a person in a situation who is less knowledgeable or skillful than others. Information security professionals would identify end-users as the weakest link to support implementing technical controls and safeguards to manage end-user behavior, rather than taking a constructive approach to educating users and helping them improve their understanding of information security risks and best practices.

The 2020–2021 global coronavirus pandemic has propelled information security educators, training personnel, and communicators to drastically reconsider how we educate users about information security practices. The quick move to remote work has heightened the need to make sure that users are informed about and empowered to implement information security practices in their remote working environments because technical controls can’t always work in an environment not managed by a central IT organization.

It hasn’t been easy. Everyday challenges exacerbated by the pandemic include:

- Users are overloaded with information. We live in a society where 24/7 news channels label every story as “breaking news,” and email, chat, and social media feeds are full of “information you need to know today!” The glut of communication, most of which is digitally delivered and not personally conveyed, makes it easy to ignore the deluge or to tune out communications that seem repetitive. With multitasking as the norm, attention is fleeting.

- Users are feeling burnt out. The early days of quarantine enthusiasm and pandemic bread baking are over. We have settled into a new routine of quarantine monotony and many people are mentally exhausted or fatigued from ongoing stay-at-home orders and the attendant responsibilities. Anyone facing personal challenges at home may not view work-related priorities with the same sense of urgency or importance amid a pandemic.

- Users are working from everywhere and logging more hours online. People are working from everywhere with a combination of business-owned and personal devices. This mix makes it more challenging for organizations and information security practitioners to secure and protect organizational devices, and more importantly, data. In addition, recent research shows the remote workday is lengthening, meaning that organizations need to be mindful of the need for around-the-clock monitoring and review to keep information and systems safe.

So how can we break through the noise and get creative in educating an audience that is key to protecting organizational data, information systems, and devices? Across industries, we are seeing new gamified awareness and education approaches to engage and motivate users, including virtual escape rooms, digital scavenger hunts, online games and puzzles, public service announcements (PSAs), six-word projects, and even haikus. These meaningful and fun educational approaches can be cultivated to encourage and empower people to reach out for assistance when confronted with a new information security threat. No longer the weakest link, users are now the first and last lines of defense and a critical part of the early warning system for organizational information security programs. As the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the National Cyber Security Alliance (NCSA), and countless other organizations have stated, “Cybersecurity is everyone’s job.”

Thinking Strategically About Information Security Education

Incorporating information security awareness and training into a broader information security program is nothing new. Awareness and training activities are recognized as a key component of most information security best practices frameworks. For instance, the Awareness and Training Control Family in the popular NIST information security framework requires the development of an awareness and training policy and responsible authority. It also requires training activities on specific topics such as insider threat, as well as additional training based on a user’s role in an organization. The control family also outlines requirements for maintaining training records and gathering feedback. Unfortunately, the control family does not outline how to provide this training as a strategic component of an organization’s information security program, nor does it outline how to provide effective and successful training.

Thinking strategically about technical communication is not new, but it is something that the information security profession has struggled with, likely because of the lack of technical communicators in the information security profession. For instance, recent reports from the SANS Institute, a prominent source for information security research, suggest that almost 80 percent of information security awareness professionals come from a technical background, while less than 20 percent have a non-technical background like communications and marketing professionals. While technical experts will have a strong grasp of the information security subject matter, they may not be as well-versed in training methodologies or the best ways to construct educational messaging. Strategic planning brings those perspectives together to create a comprehensive approach to information security education.

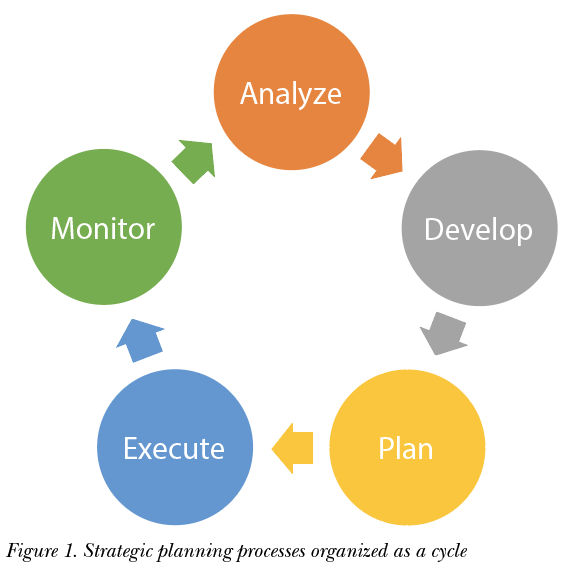

Most strategic planning processes are organized as a cycle that helps an organization understand where it’s been and where it wants to go. This type of planning can easily be applied to information security educational activities.

During the analyze stage, an organization reviews its business strategy, historical performance, and the threats that it faces to understand its current context. From an information security education perspective, the organization will review past awareness and training activities, the perspectives of its audiences, and the threats to a successful awareness program.

During the analyze stage, an organization reviews its business strategy, historical performance, and the threats that it faces to understand its current context. From an information security education perspective, the organization will review past awareness and training activities, the perspectives of its audiences, and the threats to a successful awareness program.

Following this analysis, the organization will develop a mission and vision for its information security education program. During this phase, the organization outlines the goals for the education program at both an organizational and stakeholder level. When considering stakeholder needs, the organization should consider the needs of different organizational audiences (e.g., leadership, management, individual contributors) and how information security messaging must be tailored to the role of each group.

During the plan stage, the organization conducts a gap analysis to understand how it will move from the current educational state to the future planned state. Often the gap analysis activity leads to the creation of a roadmap, which helps to outline what the organization wants to achieve and how it will accomplish the proposed goals during certain timeframes.

The execute stage is where the previous review and planning activities pay off. During this stage, the organization starts the work of executing its roadmap. From organizing events to creating awareness materials, this stage is characterized by project plans, budgets, and leading and coordinating the work of multidisciplinary teams.

No higher-level strategic planning process is complete without a phase that monitors performance and progress. As projects are completed and the organization moves forward on its information security education roadmap, measuring performance and ensuring alignment with the previously outlined mission and vision are crucial. As strategic planning is a process, not a project, the results from the monitor phase feed into the analyze stage for cyclic revisions to the plan.

Measuring the Impact of an Information Security Awareness Program

Assessing and measuring the impact of an organization’s security awareness and training program can provide insights into the effectiveness of the educational activities offered to end-users. Relevant metrics can help illustrate how program goals are being met and offer concrete data that can be shared with senior leadership.

Some sample metrics frequently used to measure security awareness program activities include the following. Note that many of these are compliance-based and may not demonstrate the true impact or reach of a more mature program:

- How many people participated in the security awareness workshop, presentation, online quiz, virtual escape room?

- How many people completed the mandatory (annual) online security awareness training module?

- What is the percentage of students, faculty, and/or staff who have received information security training (measured over time)? Has there also been a reduction of information security incidents (also measured over time)?

- For organizations running phishing campaigns via email or SMS, what were the open rates (i.e., how many recipients opened the test email/text), click rates (i.e., how many recipients clicked on the phishing link or downloaded an attachment in the test email/text), and report rates (i.e., how many recipients reported the test email/text to the help desk or IT team)?

Broader organizational metrics for an information security awareness program might include:

- What is the percentage of organizational IT budget spent on the information security awareness, training, and education program (measured over time)?

- How many people are managing the organization’s security awareness and education program (total number of FTEs)?

- What is the percentage of organizational IT staff who receive additional training on how to incorporate information security best practices into their daily job function (measured over time)?

Besides the metrics mentioned above, consider including some “outside the box” key performance indicators (KPIs). While these suggested KPIs might not provide measurable values for an organization, they can be used to demonstrate some of the important work being done through an information security program to raise awareness and build community.

- Are people reaching out to the infosec team, IT staff, or the help desk with questions about security? A good security awareness and training program should create and encourage opportunities for dialogue with users across the organization. Consider tracking the number of emails, phone calls, or Slack messages from employees about security-related issues, which may signal that users trust the infosec or IT team and see value in the team’s expertise.

- Are partnerships being built across the organization with other departments like marketing, finance, or operations? Developing and nurturing relationships can help people understand and appreciate the role of a security awareness professional and why training is so important.

- Are security ambassador programs being leveraged to help boost information security awareness efforts across departments? For organizations that do not have a dedicated security awareness professional, an IT team can identify volunteers to help share security awareness communications and educational resources. Track the number of ambassadors (also referred to as champions or advocates), the number of employees each ambassador reaches, and the number of communications shared by the ambassadors.

Seizing Opportunities to Change Security Awareness and Education

Winston Churchill stated, “A pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity; an optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.” Security awareness professionals and technical communication professionals who are tasked with information security educational roles are constantly finding new opportunities to take an optimistic approach. Rather than allowing current challenges like limited attention spans to become obstacles, we’ve observed people trying more creative approaches to develop useful (and witty) content to reach diverse audiences. We weren’t expecting sea shanties to become popular in the 21st century, but why not embrace this entertaining trend? There is already one security-themed sea shanty written by a well-known social engineer and hacker, Rachel Tobac, which might provide inspiration.

Sea shanties are just one example of modern, engaging content that can be leveraged for end-user awareness. Another approach for our growing work-from-anywhere culture might be to host regular virtual office hours or “Ask Me Anything” (AMA) sessions. Offering informal chances for users to bring their security questions or concerns to an expert can demonstrate how approachable the team truly is and might offer a welcome break (and some levity) in people’s workday. These slightly unconventional approaches to education can encourage curiosity and create opportunities for ongoing dialogue between educators and users. The content is fun, doesn’t present information in an overwhelming way, and shouldn’t cause people to overthink security or feel intimidated. Other creative examples can be found on social media, in publications, and online forums, or simply by talking with our peers. If we want to continue seizing these moments to proactively educate people about cybersecurity in more organic and meaningful ways, we should continue sharing ideas within the community.

People, processes, and technology will continue to be the primary pillars of cybersecurity. But perhaps by intentionally shifting our focus to people, empathy, and authentic engagement, we can help make information security more inclusive and accessible to users.

JOANNA GRAMA (joanna.grama@vantagetcg.com) is an Associate Vice President at Vantage Technology Consulting Group. She has more than 20 years of professional expertise in law, higher education, information security and risk, and data privacy. Joanna’s passion is helping organizations successfully evolve their information security, privacy and risk programs.

VALERIE VOGEL (Valerie.Vogel@VantageTCG.com) is a Strategic Consultant at Vantage Technology Consulting Group. She has more than 20 years of experience in higher education information security, focusing on program management, awareness and education program development, and community building activities. Before joining Vantage, she was Senior Manager of the EDUCAUSE Cybersecurity Program.

References

Learn more about information security awareness professionals and information security education programs with these resources.

Barker, Jessica. 2019. “The Human Nature of Cybersecurity.” EDUCAUSE Review. Accessed 25 February 2021. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2019/5/the-human-nature-of-cybersecurity.

EDUCAUSE podcast. 2020. “Privacy and Security: The Six Words Project.” Accessed 25 February 2021. https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2020/9/privacy-and-security-the-six-words-project.

Grama, Joanna. 2017. “Metrics Mania! Review.” EDUCAUSE Review. Accessed 25 February 2021. https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2017/9/metrics-mania-review.

Harvard University. 2021. “Cybersecurity Awareness Month Digital Scavenger Hunt.” Accessed 25 February 2021. https://security.harvard.edu/ncsam-2020-digital-scavenger-hunt.

Mancini, Steve. 2019. “Cyber Security Training Haikus: No Heads in the Sand.” BlackBerry ThreatVector Blog. Accessed 25 February 2021.

https://blogs.blackberry.com/en/2019/05/cyber-security-training-haikus-no-heads-in-the-sand.

Renner, Rebecca. 2021. “Everyone’s Singing Sea Shanties (or Are They Whaling Songs?).” The New York Times. Accessed 25 February 2021.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/13/style/sea-shanty-tiktok-wellerman.html.

SANS. 2019. “2019 SANS Security Awareness Report.” Accessed 25 February 2021. https://www.sans.org/security-awareness-training/reports/2019-security-awareness-report.

Spitzner, Lance. n.d. “Security Awareness Metrics.” Accessed 25 February 2021. https://www.sans.org/security-awareness-training/blog/security-awareness-metrics.

Temple University. 2020.“Student Cybersecurity Awareness Month Public Service Announcements.” Accessed 25 February 2021.

https://sites.temple.edu/care/multidisciplinary-learning/mel-activities/.

Tobac, Rachel. 2021. Sea shanty post. Twitter. Accessed 25 February 2021. https://twitter.com/racheltobac/status/1352409636792492035.

University of Virginia. 2020. “Virtual Escape Room.” Accessed 25 February 2021. https://security.virginia.edu/Cybersecurity-Awareness.

Woelk, Ben. 2019. “Wind, Trees, and Security Awareness.” EDUCAUSE Review. Accessed 25 February 2021. https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2019/9/wind-trees-and-security-awareness.