By Sean Scheibe

I was recently assigned a class project to edit a manual for a “Beavertail” hitch-pull trailer, named for the sloped extension on its rear trailer frame. As an editor of information technology (IT) documents, which concern software instructions, I was bewildered how to approach editing this type of mechanical content. I had no inkling at the time that this assignment would be a serendipitous event in my career development as an editor.

This subject matter involved mechanical — i.e., moving — components used for transporting various payloads on an interstate, as opposed to computers, whose data “payloads” are directed virtually over an information superhighway! However, after taking a metacognitive step back and pondering these documents through a lens of genre, I realized this deck of trailer manuals followed the same conventions and fulfilled the same purpose as IT documents do. I had stumbled upon the problem-solving power of genre.

This subject matter involved mechanical — i.e., moving — components used for transporting various payloads on an interstate, as opposed to computers, whose data “payloads” are directed virtually over an information superhighway! However, after taking a metacognitive step back and pondering these documents through a lens of genre, I realized this deck of trailer manuals followed the same conventions and fulfilled the same purpose as IT documents do. I had stumbled upon the problem-solving power of genre.

Genre Can Shorten the Learning Curve on a New Project

Regardless of the subject matter, I had found that, “genre provides a place to start, topically and structurally.”1 A genre is defined by its style, content, context, rhetorical purpose, and form, which is recognizable in reports, proposals, and in this case manuals. Recognizing that audiences have clear expectations for a genre’s content and format provided me with a clear path forward. Understanding the grammatical, formatting, and formulaic conventions that define the “manual” genre would save me time in the appraisal of this document and focus my efforts at editing more effectively by recognizing what key elements define a manual’s explanatory contents.

Hitch-pull trailer maintenance and operation presented me with a largely foreign subject matter; however, I realized the trailer manual content on a deeper level, as a genre, employed present tense, explanatory text in a nearly identical manner to IT documents, which use a present-tense imperative sentence construction. Procedures and checklists would be governed by the same conventions. The audiences of IT field service technicians and trailer vehicle mechanics/operators are different, but the rhetorical purposes of a deck of documents for them are the same — clear instructions to perform equipment maintenance. Facing an unknown subject and rhetorical context, I could still, “depend upon some of the conventions and expectations that the [manual] genre already provides.”1

Hitch-pull trailer maintenance and operation presented me with a largely foreign subject matter; however, I realized the trailer manual content on a deeper level, as a genre, employed present tense, explanatory text in a nearly identical manner to IT documents, which use a present-tense imperative sentence construction. Procedures and checklists would be governed by the same conventions. The audiences of IT field service technicians and trailer vehicle mechanics/operators are different, but the rhetorical purposes of a deck of documents for them are the same — clear instructions to perform equipment maintenance. Facing an unknown subject and rhetorical context, I could still, “depend upon some of the conventions and expectations that the [manual] genre already provides.”1

I became aware of this truism as the trailer company’s lead engineer provided me with details on both the manual content and its intended audience and rhetorical focus. Using genre to appraise the mechanical subject matter of these trailer manuals was instrumental in creating an effective editing plan, which would enable me to adapt familiar conventions to the new subject matter. Audiences, terms, and the content all had different names, but were governed by the same conventions.

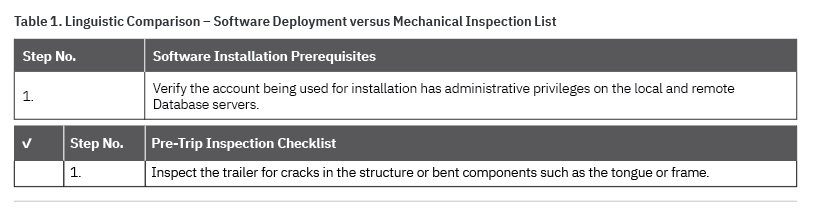

Sentence construction, table, and procedural formats shared by these rhetorical communities is exemplified in Table 1, which provides an example of the adaptation of IT table structures to the context of trailer vehicle maintenance. The Microsoft Style Guide suggests that writers dealing with this type of content use an imperative mood, which uses an active voice. Table 1 illustrates how the imperative mood works interchangeably between virtual and physical subjects.

Understanding the Limitations of Programmatic Editing

Academic awareness of the power of genre provided me with an effective tool to employ in my workplace and to understand the limitations of programmatic editing. Editing that is solely guided by the program — or house style guide, grammar, etc. — is an efficient way to edit. However, this approach overlooks fruitful areas of rhetorical awareness and development that an editor can cultivate outside the constraints of prescriptive rules. According to Mary Fran Buehler, “The best example of a programmatic approach in technical communication is the application of ‘correct’ grammar, spelling, and punctuation, without concern for all the varied elements of the [rhetorical] situation itself.”2 Instead of programmatic editing, a focus on genre and its related rhetorical situation(s), audience, and so forth allows an editor to collaborate in the creation of knowledge as an authentic outgrowth of participation in a community and its linguistic traditions.

When I started as an editor for the Navy Marine Corps Intranet (NMCI), I learned that one of my primary roles was to ensure the uniformity of documents to our house style guide. This was an efficient way to view our roles as editors and was reflected in one of our team’s goals, which is “to apply editing expertise that ensures documentation is produced in accordance with consistent and approved formats and document standards.”

This is a solid foundation upon which to edit, but it omitted answers to questions such as, “Should we define a term based on how it is used colloquially in our rhetorical community, or use the term in our documents as it is defined in our glossary?” Based solely on our glossary, one particular term would be defined as Alternate Logon Token (ALT), which is a network access device. However, within the network support teams the term is spoken as “ALT token” — not ALT — or “Alternate Logon Token.” Our editorial team has the discretion to treat the term in our IT documents as it’s spoken, not as it’s defined in our glossary. This is the difference between understanding a term as grammatically versus rhetorically correct and follows Carol Miller’s axiom, “To write, to engage in any communication, is to participate in a community; to write well is to understand the conditions of one’s own participation — the concepts, values, traditions, and style which permit identification with that [rhetorical] community…”3 Our NMCI documentation accurately reflects that community’s colloquial style and linguistic traditions.

Applying Tools to Make the Best Choices

Tempering the dictates of a house style guide with an awareness and understanding of genre is the difference between editing programmatically or editing by the rhetorical situation and genre. Using style guides and grammar as tools rather than as editorial manacles ensures the editor can ascertain the best choice for the rhetorical situation, not merely the correct choice.

Until this class assignment came along, I hadn’t had the opportunity to use the editorial principles and skills I had learned to appraise documents with different types of subject matter. Using genre and rhetorical analysis to appraise trailer vehicle manuals provided me with the capability to bridge my understanding and skills to an entirely new subject matter — and at the same time gain confidence as an editor.

Editing Strategies to Consider

- Use genre expectations to efficiently appraise and edit even the most unfamiliar documentation.

- Assess genre, purpose, audience, context — rhetorical situation — to uncover the audience expectations and conventions. This is instrumental in appraising the document as an editing plan is composed.

- Determine the expectations and needs of the reader to accurately match the genre of the document.

- Align conventions of the text — such as verb tense, usage, and prevailing sentence patterns — with audience needs.

- Anticipate and respond effectively to various rhetorical situations that might be different, but are unified by the social purpose and genre of the text.

SEAN SCHEIBE (seanscheibe@u.boisestate.edu) worked for Peraton as a Technical Editor in support of the Navy Marine Corps Intranet (NMCI). Last year, he enrolled in the Boise State University technical communication program and hopes to complete his Certificate in Technical Communication in Spring 2022. One of his recent accomplishments was being added to the quality check (QC) rotation within a senior group of editors, where they edit each other’s documents prior to finalization.

References

- Henze, Brent. 2013. “What Do Technical Communicators Need to Know about Genre?” In Solving Problems in Technical Communication, eds. Johndan Johnson-Eilola and Stuart A. Selber Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press: 337-361

- Buehler, Mary Fran. 2003. “Situational Editing: A Rhetorical Approach for the Technical Editor.” Technical Communication, Vol. 50, No. 4 (November): 458-464

- Miller, Carolyn R. 1979. “A Humanistic Rationale for Technical Writing.” College English, Vol. 40, no. 6 (February): 610-617