Leveraging unstructured feedback and user-generated content can improve the user’s experience

The rise of Web 3.0 and its emphasis on technologies that enable personalization, as well as peer-to-peer (or customer-to-customer) interactions, provides new opportunities for users to generate content. Social media entertainment platforms, such as Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube, as well as databases that crowdsource information about health-related issues (e.g., Stuff That Works), increasingly allow users to contribute information. For instance, users of these technologies might write a review about a product or service, post a comment intended to help another user troubleshoot a software or hardware issue, or provide other kinds of feedback, such as health-related advice.

Creators or developers of these technologies then might use this information to make changes to their product or service. Such information is commonly referred to as user-generated content (UGC). UGC can take the form of text, images, videos, or audio, and it has proliferated exponentially over the past few years. For instance, have you ever reviewed or read about a product you bought through Amazon? Posted, liked, or shared a comment in an online discussion forum, such as Reddit? If so, you’ve created or interacted with UGC. As several scholars working in advertising and media studies defined the concept, UGC is “content created or produced by the general public rather than by paid professionals and primarily distributed on the Internet.”1

UGC is widely available, and it’s also highly valuable. UGC can be sponsored, staged, or unfiltered. It can also be created spontaneously for content creators’ or users’ followers. For example, UGC might take the form of a comment about an app posted on Google Play or the App Store; a review for a local restaurant on Yelp or TripAdvisor; or even information for a mobile health (mHealth) app, such as the fitness tracker Fitbit, which records exercise, movement, and sleeping habits; or Glucose Buddy, which helps users manage diabetes. Indeed, many people find the comments and opinions of other users/customers more credible than information from companies and organizations. And they use UGC to make decisions about what products, services, or technologies to buy. Scholars in technical and professional communication, too, have recognized the importance of UGC, arguing that this information can be used to better understand users’ needs in particular contexts, such as improving the usability of technology products. When unfiltered, UGC can offer a unique and rich source of valuable feedback and untapped data to better understand how users use products, software, or other items.

In this article, we focus on how technical communicators can apply UGC to improve the usability of smartphone apps by briefly addressing two interrelated questions:

- How might UGC be leveraged to improve the usability of apps?

- How can users be prompted to provide valuable UGC feedback?

Leveraging UGC to Improve App Usability

Usability research on apps often tends to focus on functional usability — that is, whether the app actually works and if users can use it effectively to perform the tasks it was designed for. To illustrate, let’s say you want to use a fitness tracker to record your daily walk or run. After your activity, you open the app on your smartphone linked to the tracker. When you do, you expect to be able to use the app to determine how far you went and how long it took you to go that distance. Depending on how sophisticated the tracker and the app are, you might also expect to access other information that the device collected, such as your heart rate at different points during your activity or a map of the route you took. If you have trouble performing these kinds of tasks, most likely you are experiencing a functional usability problem.

Usability testing with users is usually designed to resolve these kinds of issues. To be sure, ensuring that apps (and their associated technologies) function as they should and are easy to use is crucial, as usability researcher Barbara Mirel explains.2 However, focusing on usability only from this perspective can emphasize the interests and needs of app developers and creators (or those who commission their work) rather than users. As scholars in technical and professional communication found, users often have their own goals and objectives when they use digital technologies, which may be different from what designers and creators of those technologies envisioned.3

UGC related to apps often takes the form of review comments, wherein users may write about their specific experience using the app and/or what they liked or disliked about using it. Such information is often unstructured because in product and technology reviews, users discuss what they want to discuss. In considering how this form of UGC might be leveraged to improve the usability of an app, there are both pros and cons. On the one hand, review comments can lend important and specific insight into what users (rather than app developers or creators) care about, which can be used to make improvements to better meet users’ needs. On the other hand, not all comments will be helpful. Indeed, many users might provide comments — as we found in our study4 on technical communication, UGC, and the mHealth apps created by PulsePoint — that aren’t actionable, such as simply stating they do or don’t like the app without explaining why. In the next section, we address this challenge by providing strategies that technical communicators who work in app development and usability can use to elicit more valuable UGC from smartphone app users.

Prompting Users

If you own a smartphone or tablet, chances are you’ve downloaded an app before. And if you used it, you may have seen a pop-up screen a few weeks later asking you to rank it: “Enjoying [app name]? Tap a star to rate it.” Asking users to provide this kind of rating assessment is quick and easy, and it can increase an app’s popularity. Conversely, inviting users to provide a more detailed assessment in a review is more time consuming. Yet with prompting, we suggest, reviews can provide specific, actionable information that can then be used to improve the user’s experience. To do so, we provide the following suggestions and examples based on findings in Welhausen and Bivens:4

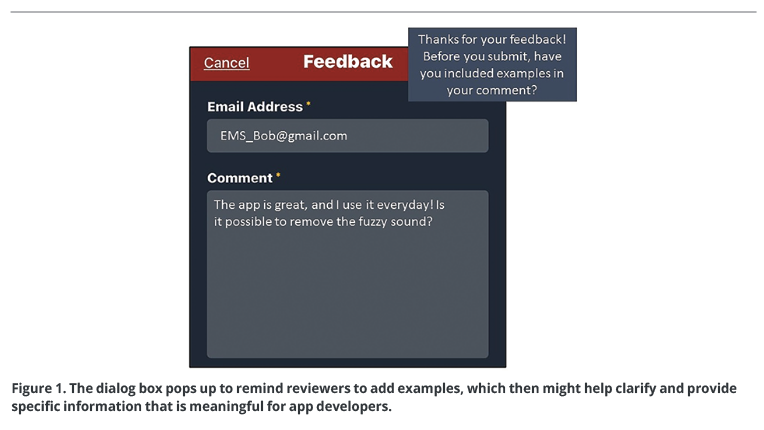

- Include a dialog box that appears after users click the “Submit” button that asks them to add examples to their review (Figure 1).

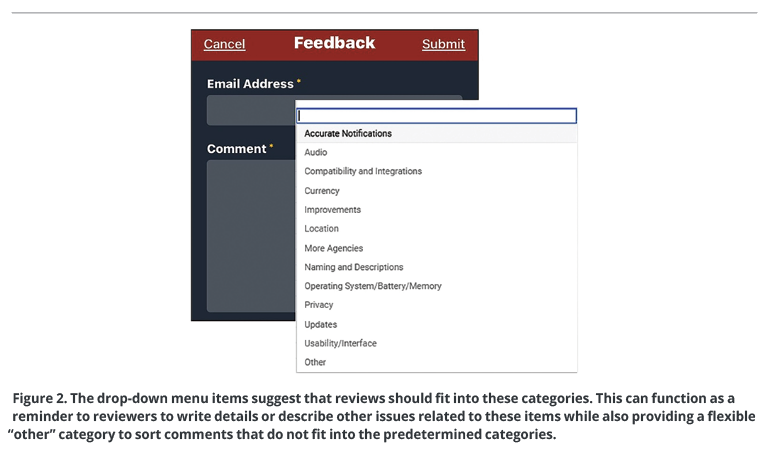

- Help users meaningfully sort their reviews by including a drop-down menu on the review screen with predetermined categories. Users can then select the category that their review best represents (Figure 2).

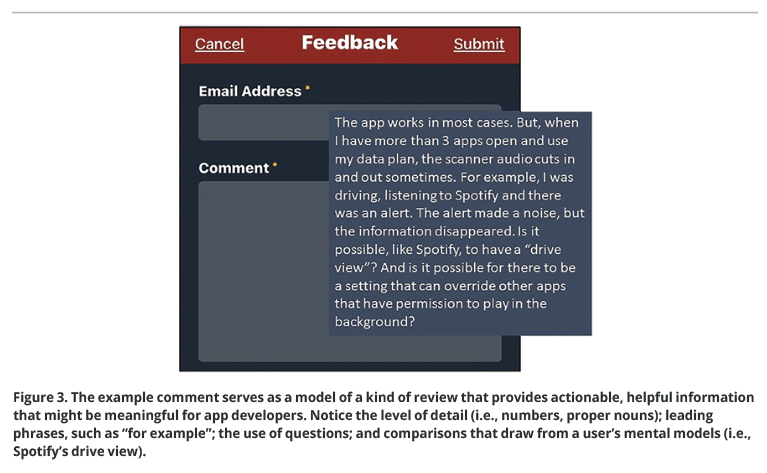

- Provide an example of an actionable kind of review that users can model in their review — that is, statements that ideally demonstrate a claim and provide support (Figure 3).

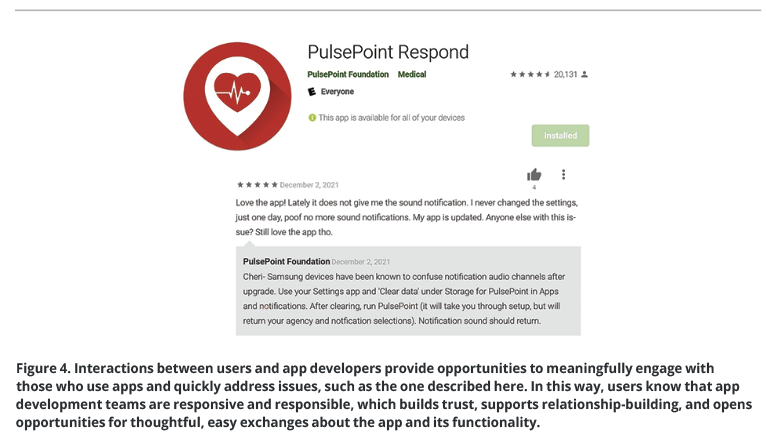

- Be sure to respond to reviews and interact with comments (Figure 4).

Concluding Thoughts

UGC does not replace traditional usability testing or other methods, such as observations, that technical communicators can use to learn about audiences and usability. Rather, it offers a complementary view, as well as arguably a more user-centered perspective, by focusing on unstructured user feedback. As technology continues to advance and machine learning systems become more sophisticated, it may also be possible for app developers to construct artificial intelligence algorithms or augmented intelligence tools that provide more nuanced prompts for users when they complete reviews. For instance, future interfaces may be able to determine which app features the user is describing and provide specific prompts to help guide their feedback.

UGC does not replace traditional usability testing or other methods, such as observations, that technical communicators can use to learn about audiences and usability. Rather, it offers a complementary view, as well as arguably a more user-centered perspective, by focusing on unstructured user feedback. As technology continues to advance and machine learning systems become more sophisticated, it may also be possible for app developers to construct artificial intelligence algorithms or augmented intelligence tools that provide more nuanced prompts for users when they complete reviews. For instance, future interfaces may be able to determine which app features the user is describing and provide specific prompts to help guide their feedback.

Ultimately, UGC will continue to proliferate, and we are still in the process of identifying all the ways it might be used to learn more specific information about users. As such, UGC will continue to offer novel opportunities for practitioners to mine this valuable, rapidly expanding source of user-driven information, thereby improving quality and satisfaction with smartphone apps.

References

1.Daugherty, Terry, Matthew S. Eastin, and Laura Bright. 2008. “Exploring Consumer Motivations for Creating User-Generated Content.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 8(2): 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2008.10722139.

2.Mirel, Barbara. 2004. Interaction Design for Complex Problem Solving: Developing Useful and Usable Software. Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann.

3.Simmons, W. Michele, and Meredith W. Zoetewey. 2012. “Productive Usability: Fostering Civic Engagement and Creating More Useful Online Spaces for Public Deliberation.” Technical Communication Quarterly 21(3): 251–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2012.673953.

4.Welhausen, Candice A., and Kristin Marie Bivens. 2021. “mHealth Apps and Usability: Using User-Generated Content to Explore Users’ Experiences with a Civilian First Responder App.” Technical Communication 68(3): 97–112.

KRISTIN MARIE BIVENS (kristin.bivens@ispm.unibe.ch) is the scientific editor at the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine at the University of Bern in Switzerland. She is also an associate professor of English at Harold Washington College, one of the City Colleges of Chicago. She is on leave during the 2020–2022 academic years. Her research examines the circulation of information from expert to nonexpert audiences in critical care contexts (e.g., intensive care units, sudden cardiac arrest, and opioid overdose) and how rhetoric and technical communication can ameliorate these situations.

CANDICE A. WELHAUSEN (caw0103@auburn.edu) is an assistant professor of English at Auburn University with expertise in technical and professional communication. Before becoming an academic, she was a technical writer/editor at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in the department formerly known as Epidemiology and Cancer Control. Her scholarship is situated at the intersection of technical communication, visual communication and information design, and the rhetoric of health and medicine.