By Elena Kalodner-Martin

As a technical and professional communication (TPC) graduate student, practitioner, and instructor, I spend a lot of time thinking about what it means to “do” socially just technical communication work, which seeks to “amplify the agency of oppressed people — those who are materially, socially, politically, and/or economically under-resourced” in “collaborative and respectful” ways.1 I am particularly interested in considering social justice technical communication in the classroom, where I (and many other instructors) are constantly navigating our commitments to social justice, with the ever-present pressure to do what teachers are supposed to do in humanities departments: help students get jobs.

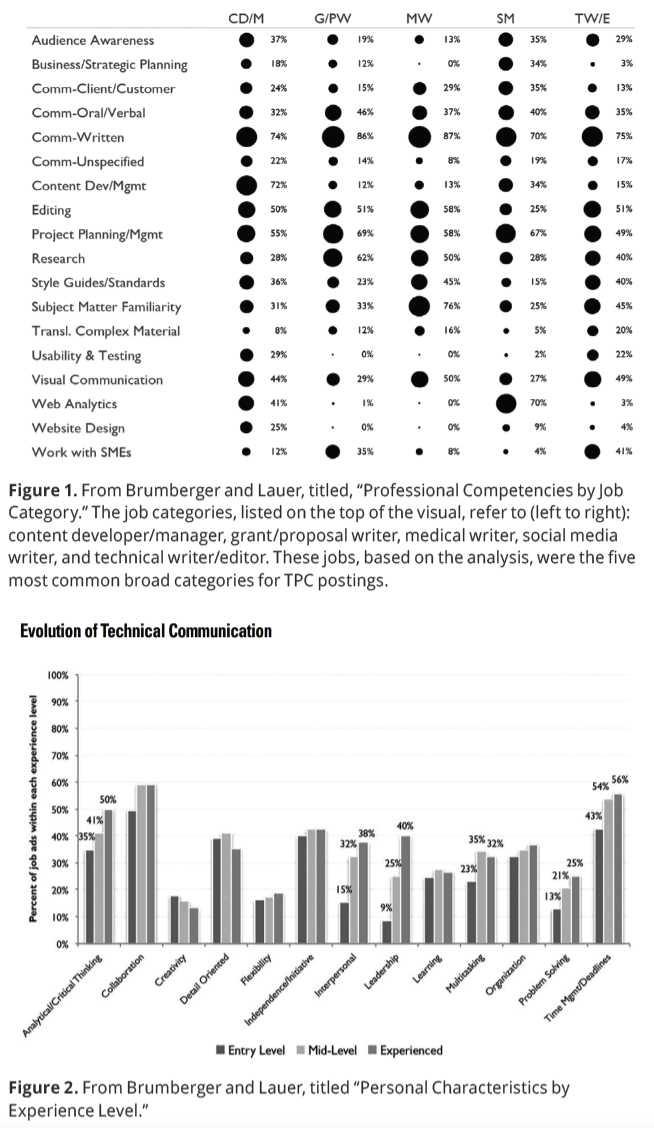

These tensions are threaded throughout TPC scholarship. Based on an analysis of TPC job postings, a 2015 report2 identified the desirable professional competencies (Figure 1) and personal characteristics (Figure 2) for applicants, ranging from subject matter familiarity and strong written communication skills to the ability to multitask, think creatively, and work collaboratively. More recently, a 2021 study3 examined how curricular efforts in TPC programs have been shaped by the increasing commitments to social justice, with references to how this might be strategically developed in classroom settings. What would it look like to bring these conversations together? Put differently: how can we view social justice as a goal not just of our classroom curricula, but also as an integral part of our workplace preparation efforts?

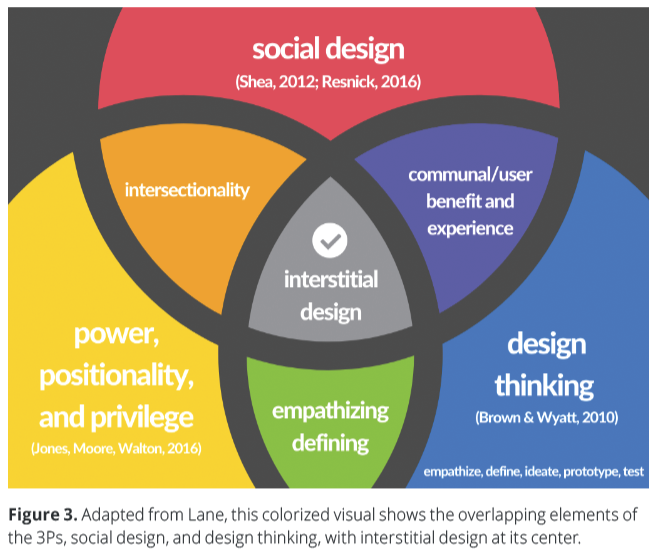

As part of my contribution to this work, I draw from interstitial design, an iterative and interdisciplinary approach to “solv[ing] complex problems in a socially engaged world.”4 Interstitial design (Figure 3) draws from the concept of interstitiality, or “in-betweenness,” to account for the overlap between social design, design thinking,5 and power, positionality, and privilege (3Ps). The 3Ps are “macro-level concepts that ground the enactment of socially just technical communication”6 and guide discussions of social justice both inside and outside classroom settings. As such, interstitial design does not just provide concrete and tangible skills for technical communicators or promote the identification of social issues, but also offers a flexible framework for interrogating who designs solutions, for whom, and under what circumstances. Interstitial design also opens up possibilities; by expanding discussions of what TC “is” and “does” past a particular author, genre, or site, interstitial design allows TC competencies and skills to flourish in personal, professional, and pedagogical settings.

As part of my contribution to this work, I draw from interstitial design, an iterative and interdisciplinary approach to “solv[ing] complex problems in a socially engaged world.”4 Interstitial design (Figure 3) draws from the concept of interstitiality, or “in-betweenness,” to account for the overlap between social design, design thinking,5 and power, positionality, and privilege (3Ps). The 3Ps are “macro-level concepts that ground the enactment of socially just technical communication”6 and guide discussions of social justice both inside and outside classroom settings. As such, interstitial design does not just provide concrete and tangible skills for technical communicators or promote the identification of social issues, but also offers a flexible framework for interrogating who designs solutions, for whom, and under what circumstances. Interstitial design also opens up possibilities; by expanding discussions of what TC “is” and “does” past a particular author, genre, or site, interstitial design allows TC competencies and skills to flourish in personal, professional, and pedagogical settings.

In what follows, I provide brief overviews of several students’ grant proposals from one of the TPC classes that I teach as a graduate Teaching Associate. Introduction to Professional Writing, the gateway course for students entering the undergraduate Professional Writing and Technical Communication (PWTC) certificate program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, is an upper-level class that familiarizes students with common genres in TPC workplaces, such as job documents, memos, and professional presentations. However, grant proposals, addressed to a funding agency on behalf of a nonprofit, are the central focus for this class. Students spend much of the semester following an interstitial design-informed protocol that asks them to consider their own values, identify a pressing social concern, conduct background research, identify partners, compose a document that asks for funding or resources in support of their intervention, gather feedback, and finally, revise accordingly. Throughout this process, students and I navigated the following questions:

- How can we ground our discussion of the “problem” and our proposed solution in our target audience’s lived experiences and local needs?

- How does our positionality, and the subsequent privilege and power that we gain from this, shape our understanding of the issue and proposed intervention?

- How can technical communicators use grant proposals to advocate for underserved communities?

Many students’ proposals in the class were geared towards addressing a pressing problem within the immediate community. For example, Isaiah’s grant proposal was grounded in the increasing prevalence of homelessness and housing instability across the nation and the simultaneous lack of educational resources for students on campus. He sought funds for seminars about homelessness education and intervention. His three workshops, outlined alongside the expertise of a state agency for homelessness prevention, were designed to be inclusive of a general audience’s knowledge while providing concrete resources for future activist efforts both on and off campus.

Another student, Emma, approached thinking about campus’ affordances differently. Her proposal requested financial assistance for a bra and menstrual product drive, with plans for the collected items to be distributed to low-income people and families across the state with the help of a local nonprofit partner. She reasoned that, with so many students wanting to get rid of things as they move out of campus housing at the end of the semester, it is likely that these highly-needed (and often inaccessible) materials would be easy to collect and would reduce unnecessary waste.

However, a couple of students also composed proposals that could address issues of inequity across the nation. Jeremy, informed by his passion for writing, designed a creative writing workshop for underserved youth at a community center in Washington State. His grant proposal interrogated the many barriers to extracurricular activities and challenged the ways that institutional writing “progress” is often measured by metrics that reinforce patterns of marginalization along raced and classed lines.

Another student, Zane, also considered structural barriers within formal education and proposed community-oriented alternatives. He focused on issues of diversity and inclusion in predominantly white state of Vermont, and he deftly wove his research into economic, social, and cultural influences for institutional racism into his proposed intervention for racial justice education seminars.

As students and I explore, there’s a lot of technical work in grant proposals: complicated information to relay about existing problems and potential solutions, complex data to draw from, and a wide range of professional experts and stakeholders to consider. They researched, outlined, wrote, analyzed, discussed, presented, and revised these documents, all while confronting weighty issues of injustice and inequality.

Interstitial design supported the class throughout this process, and these brief examples do not do justice (pun intended) to the depth and complexity of these proposals. This case reveals that grant proposal assignments, guided by interstitial design, can support students in honing professional skills, developing genre knowledge, and furthering their technical capabilities while simultaneously centering the complexities of social justice work.

This case is just one example of the many ways that teachers can (and undoubtedly already do) prepare students for professional careers while still practicing a social justice pedagogy. However, there is still more work to be done. By bringing together ideas of what it means to demonstrate workplace competencies alongside commitments to inclusivity, equity, and access, I suggest that all of us — technical communication educators, program administrators, scholars, practitioners, and more — can continue to shape a more justice-oriented field, both within our classrooms and beyond.

References

- Jones, Natasha N., and Rebecca Walton. 2018. “Using Narratives to Foster Critical Thinking about Diversity and Social Justice.” In Key Theoretical Frameworks for Teaching Technical Communication in the 21st Centtury, edited by Michelle Eble and Angela Haas, 241–267. Utah State University Press.

- Brumberger, Eva, and Claire Lauer. 2015. “The Evolution of Technical Communication: An Analysis of Job Postings.” Technical Communication 62 (4): 224–243.

- Agboka, Godwin Y. and Isidore K. Dorpenyo. 2021. “Curricular Efforts in Technical Communication After the Social Justice Turn.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication 36 (1): 38–70.

- Lane, Liz. 2021. “Plotting an Interstitial Design Process: Design Thinking and Social Justice Processes as Framework for Addressing Social Justice Issues in TPC Classrooms.” In Equipping Technical Communicator for Social Justice Work: Theories, Methodologies, and Pedagogies, edited by Rebecca Walton and Godwin Agboka, 214–230. University Press of Colorado.

- Ibid, 217.

- 6.Walton, Rebecca, Kristen R. Moore, and Natasha N. Jones. 2019. Technical Communication After the Social Justice Turn: Building Coalitions for Action. Routledge.

Elena Kalodner-Martin is a PhD candidate in composition and rhetoric at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Her research interests are at the intersections of technical communication, the rhetoric of health and medicine, and intersectional feminist studies. She is also a research writer at Untold Content, an innovation storytelling firm.