By Katherine (Kit) Brown-Hoekstra | STC Fellow

Find the optimal tool for your needs by asking the right questions.

We have all been there. Some executive hears about a shiny new tool that is marketed to solve all our problems, and we find ourselves in the midst of a major technology overhaul, often without adequate discovery, analysis, and planning. This approach all but guarantees that the initiative will fail to meet expectations because no amount of technology will solve your people and process issues, especially if you don’t understand the business problem you are trying to solve.

So, what can we do to ensure our technology initiatives are successful?

Discovery

Depending on the complexity of the project and the information available, discovery can be relatively quick or can take weeks or months, and includes the following tasks:

- Understand the scope of the challenge and what business problem you need to solve.

- Understand how the project fits with corporate objectives, and ensure that the team knows and is aligned on the priorities.

- Ensure that the budget, as well as technical and human resources, are available.

- Identify key stakeholders.

- Evaluate the current states of the technology, people, and processes.

- Identify assumptions and constraints, as well as strengths and opportunities.

- Develop the vision statement for the project.

- Begin change management (the human kind).

If you aren’t clear about your objectives, assumptions, and constraints, the discovery process can devolve into a rabbit hole. Formulating and asking the right questions can help prevent this.

Asking Good Questions

As David Cooperrider, founder of Appreciative Inquiry, says, “Words create worlds.” The questions we ask lead us down certain avenues of investigation. If the questions focus only on the problem or are worded negatively, we can derail our objectives before we even begin. Instead, we want to create generative questions that lead us to build on our strengths and tap into the collective knowledge hidden in our teams. To do this, the XCHANGE community (http://www.xchangeapproach.com) recommends some simple rules:

- Make the questions generative and expansive by focusing on the vision, not the problem. For example, ask, “How might we create an outstanding customer experience?” NOT, “How do we fix our customer turnover rate?”

- Frame the questions positively. Use positive, solution-oriented language that leads to creativity, not to the complaining and kvetching that leads to more reactivity. For example, say, “What if we…” NOT, “Why can’t we…?”

- Use active voice, present tense.Action verbs and present tense get our brains into the mental space of taking positive steps toward our goals.

- Make the questions open-ended. In discovery, we want to gather as much relevant information as we can as efficiently as possible. Close-ended questions that have binary answers shut down the conversation. Ask, “What kinds of process documentation do you have available?” instead of, “Do you have…?”

- Ask follow-up questions. Follow-up questions help the stakeholders dive deeper into the topic at hand and help them excavate pertinent data and information that they didn’t know they knew. When asking questions in a workshop or interview, a key part of the follow-up questions is to pause and give stakeholders space to think before responding. Get comfortable with silence. Sometimes, the follow-up can be as simple as, “Please tell me more.” Or, “Your comment about X is interesting. How does it impact Y?”

Warren Berger’s book and blog, A More Beautiful Question, provide additional examples and recommendations for wording effective questions.

Conducting Workshops

Discovery workshops allow you to crowdsource the business requirements and, when done well, can be an efficient way to work with larger groups of stakeholders. They also help you begin change management by helping to: 1) make the stakeholders part of the solutions: and 2) set/clarify expectations. In these workshops, you do lots of listening and very little talking. The exact structure of the workshop varies depending on your specific objectives, but generally follows this format:

- Introductions

- Expectations and Objectives

- Stage Setting for the Exercise

- Small Group Exercise (groups of three to five)

- Discussion of Exercise

- Next Exercise.

While you can use this in a small team, this format works best with 10+ participants so that you can break them into at least three groups. Having three or more small groups enlivens the discussion after the exercise and helps to ensure that multiple perspectives and approaches are considered. Other considerations include:

- Have someone take notes and help with technical support (especially if you are online).

- For online workshops, use Miro, Mural, or other whiteboarding tools and set up the workspace ahead of time. Miro has some great templates for exercises. Gamestorming by Dave Gray, et al. has many exercises that make the work fun and engaging.

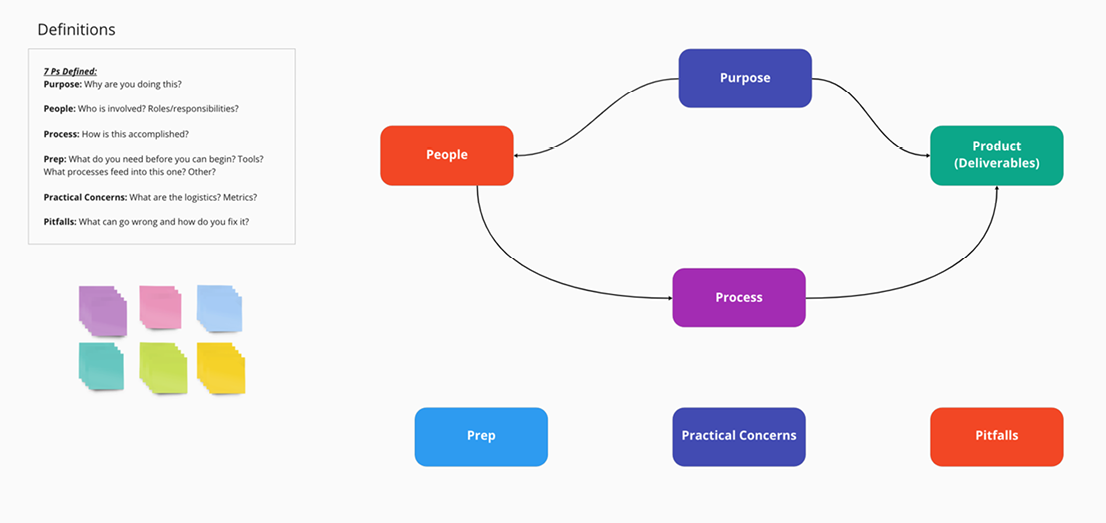

- Prepare the questions and exercises in advance, and know what you want to get out of the exercise. Connect the dots for the participants between the exercises and the larger goals. For example, if you need to know business requirements, an exercise like the 7Ps (see Figure 1) can help you identify areas of your content processes that could be automated and where issues might arise when implementing a new technology.

- Work with the project sponsor or lead to ensure that the small groups have a good mix of skills, job functions, and teams. Interesting information arises out of discussions among colleagues who don’t usually work with each other.

- Be clear about break times and lengths, expectations about being fully present. If online, don’t go for longer than two hours without a break. Split the workshop into multiple days, if it will be longer than four hours. Online workshops are more exhausting for participants than in-person ones because they are not moving around as much.

- Give explicit instructions for the exercises and, if an exercise is longer than 10 minutes, check in with the groups as they work.

When the workshops and interviews are complete, you will have loads of data to analyze and develop business requirements from.

Analysis

After Discovery, you should have a clear picture of the current state. As you begin analyzing the data, additional questions might arise, so make sure you have access to key stakeholders who can quickly answer those follow-up questions. The three levels of analysis are gap analysis, needs analysis, and business requirements or selection criteria.

Gap Analysis

Gap analysis helps you envision the roadmap between where you are now and where you want to be. Understanding the current state and the vision of successful project completion is critical to this analysis. If you aren’t clear about where you are going, any road will get you there. The analysis deliverable is a high-level roadmap that identifies the major milestones and estimated timeline between where you are and where you want to end up.

Ask these questions:

- Is the vision reasonable and achievable, or do we need to modify our expectations?

- What are the milestones for each phase of the project?

- What is a reasonable timeline?

- Who needs to be involved at each stage?

- How will we know when we have succeeded?

- Do the milestones accurately reflect the path we need to follow? Do they build on each other?

Needs Analysis

The needs analysis identifies what resources are needed at each step on the roadmap. After you have the roadmap outlined, it’s time to dive into the details of what you need in place to achieve each milestone.

Ask these questions:

- What budget is available for each stage?

- Who will manage the project? Who will be on the team?

- What resources are needed to be successful?

- How will we measure success? What is our baseline? Are our current metrics effective and sufficient? If not, what do we need to have/put? in place?

- Do the team members have the skills they need to succeed? What training needs do we anticipate? Do we need to hire anyone?

- What dependencies exist to move from one task to the next?

- What system integrations, migrations, automations, or upgrades do we need at each stage? (Technology initiatives often expose dated systems and over-customized solutions.)

- What processes need to be developed, reviewed, modified, or documented to accommodate new technology?

- What change management (both human and technical) do we need to have in place?

- How will we communicate with the team?

- What are the risks, and how will we mitigate them?

Business Requirements and Selection Criteria

The business requirements and selection criteria identify the constraints and rules for the tools, processes, and people. Business requirements often include use cases, priorities, regulatory needs, and cost/benefit analysis, and are typically higher level than selection criteria.

For example, the business requirement might state, “Authors must submit content for at least one review with the subject matter expert before publishing.” The CMS selection criterion might then state, “CMS must support a review process that tracks status and notifies reviewers when content is ready.” Note that requirements typically focus on the WHAT, not the HOW.

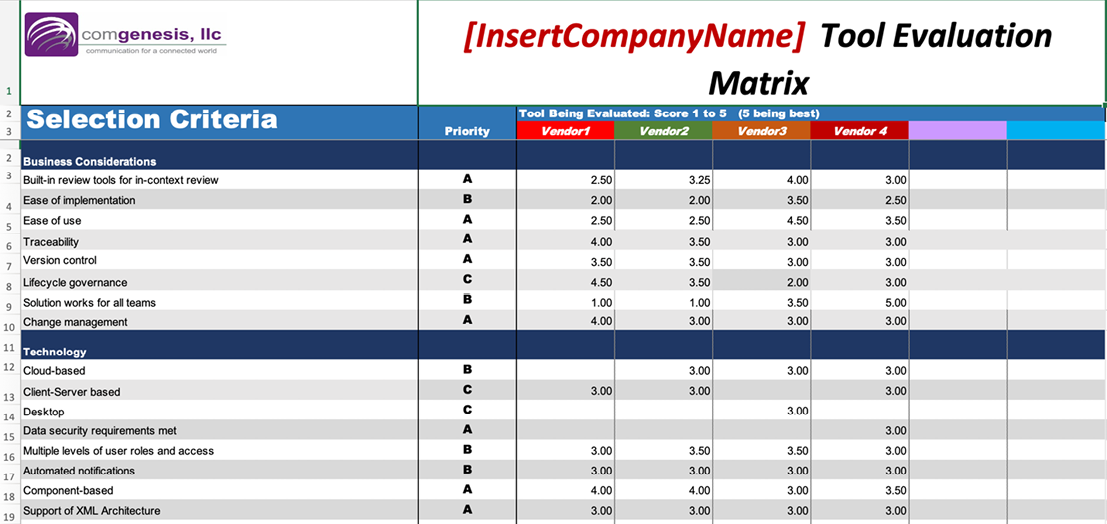

With mature technology, most systems of a particular type have similar features. What differs is how well each vendor implements these features. Depending on your priorities, you might weight criteria differently. Figure 2 shows an example spreadsheet, where the priorities are weighted A = 1.5, B = 1.25, and C = 1.0.

Defining the business requirements and selection criteria can be time-consuming and challenging if a large team is involved in the process. However, these discussions are useful for getting the team aligned and ensuring that everyone has ownership (which facilitates change management). While you want all functional areas involved to have a say, as you get closer to refining the requirements, you might need to narrow the review team to just team leads for each functional area, so that you don’t get into analysis paralysis.

As you start reviewing tools, you might discover additional criteria. Be sure to evaluate all the vendors against the updated criteria to ensure that you are doing a fair comparison.

Planning

The project manager uses the roadmap, needs assessment, schedule, and requirements to create the project plan, Gantt charts, budget requirements, team assignments, and so on. With complex technology implementations, it’s a good idea to do a proof-of-concept project with the system you are considering. Most vendors of enterprise systems expect this and have a team to assist with running the project.

Consider these characteristics for the proof of concept:

- Representative content that includes the major types and complexity of the total content ecosystem.

- Team that has the flexibility, skill, and attitude to experiment effectively (no Eeyores allowed).

- Project type that is not on a critical path and has a duration that fits the proof-of-concept timeline.

- Budget and time constraints are accommodated.

Conclusion

Discovery helps you ensure that teams are aligned on a common vision, asking good questions, and agreeing on the business requirements, as well as providing an opportunity for change management. Analysis helps you identify knowledge and data gaps, understand what metrics you need, and develop the roadmap. During analysis, you can also determine what teams, content, and outputs will best support a proof of concept. Having a clear vision and asking generative questions help ensure that your roadmap, needs assessment, and requirements are properly aligned and reasonable, and that your plans are achievable.

Kit Brown-Hoekstra is an STC Fellow and former Society President, and award-winning consultant. As Principal of Comgenesis, LLC, Kit provides consulting and training to her clients on content strategy, content operations, localization strategy, and appreciative inquiry. She speaks at conferences worldwide and publishes regularly in industry magazines.

Kit Brown-Hoekstra is an STC Fellow and former Society President, and award-winning consultant. As Principal of Comgenesis, LLC, Kit provides consulting and training to her clients on content strategy, content operations, localization strategy, and appreciative inquiry. She speaks at conferences worldwide and publishes regularly in industry magazines.