Abstract

Purpose: This article presents translation as a user-localized activity. Using Sun's (2012) distinction between user and practitioner localization, the researchers present a preliminary illustration of how translation is enacted by multilingual participants aiming to translate words from their heritage languages into English.

Method: As part of this pilot study, ten, ten-minute interviews were conducted, video-recorded, and coded to better understand how multilingual users adapt information from their heritage languages into English.

Results: Results suggest that users employ several strategies when translating in context: acting, comparing/contrasting, deconstructing, gesturing, intonation, negotiating, sketching, and storytelling. These strategies involve the use of both words and other semiotic resources (for example, gestures, intonation) to convey meaning across languages.

Conclusion: Technical communication researchers and practitioners could develop more effective translation and localization frameworks by learning from the user-localized translation practices of multilinguals. Analyzing the translation practices of multilinguals who are not professional translators or interpreters could provide a framework for technical communicators to better recognize the complexities of writing in English for international audiences.

Key words: translation, localization, user-experience

Practitioner's Takeaway

- An introduction to the concept of culturally localized translation and how it, as a process, operates

- An overview of alternative methods of working with translators to produce materials for audiences from various cultures

- An overview of alternative approaches to more conventional methods of replacement and substitution when translating materials.

Introduction

Increasingly, technical communication researchers and practitioners are acknowledging the need to create culturally sensitive, global ready content (Agboka, 2013; Sun, 2012). As Maylath et al. (2013) explain, “diversity, interdependence, ambiguity, and flux epitomize the conditions under which international professional communicators work today” (p. 68). To produce and disseminate “culture-specific information models” that address the needs and skills of global users, “best practices are needed…that stem from collaborative research on culture, translation and localization, global audience analysis, and content strategy” (Batova & Clark, 2015, pg. 5). As others have noted, the importance of cross-cultural, multilingual communication has become increasingly integral to technical communication research and practice.

Numerous researchers in technical communication are developing contemporary models for understanding the importance of culturally localizing content (Batova & Clark, 2015; Maylath et al., 2014; St. Amant, 2002; Sun, 2006; 2012). Drawing on several case studies conducted to examine the function of mobile text-messaging in China, Sun (2012) highlights the role that local users' adaptations of a technology (that is, text-messaging) can be useful in improving developer localization. User localization, Sun (2012) argues, differs from developer localization, or “the localization work occurring at the developer's site that we commonly refer to when thinking of localization” (p. 40). User-localization focuses on the specific activities and strategies users employ when communicating to meet their culturally-situated needs. Understanding user-localization, in turn, can help developers design and adapt technologies to meet the needs of users in localized contexts.

In this entry, we examine how translation and localization are enacted through what Sun (2012) calls “user localization.” By tracing the process of translation and localization as activities enacted by users in context, we aim to better understand translation and localization as culturalized activities (that is, activities that draw on users' cultural backgrounds and lived experiences). By better understanding what translation looks like when enacted by multilingual speakers (who are experts in multiple languages but not professional translators or interpreters), we believe that we can devise strategies and models for translation that are useful for technical communicators working across languages and cultures. Our goals are to

- Present a research-driven picture of what translation looks like

- Help technical communication researchers and practitioners identify places where we can learn from the rhetorical strategies of multilinguals to more effectively adapt information in international contexts.

Through approaching translation in this way, technical communicators can gain both an enhanced understanding of the expectations of audiences from various cultures and re-think how they might work with translators in the future.

Defining Translation and Localization

(Re)Defining Translation

Recently, many scholars have drawn a distinction and emphasized the connections between translation and localization (Batova & Clark, 2015; Sun, 2012). Translation, as Batova and Clark (2015) explain, often involves the replacement of one word in one language with a similar word in another language, an “attempt to duplicate meaning interlingually” (p.223). Many early uses of translation functioned under the assumption that simply replacing one word in one language with a word in another language would adapt content to meet the needs of international users (Bokor, 2011). However, as Jarvis & Bokor (2011) point out, language alone does not always produce a clear representation of a single thought or idea. Rather, it often conveys how we think about different kinds of experiences. Therefore, the simple one-to-one replacement of words from one language to another language may not account for cultural distinctions negotiated as ideas shift and move between people (p. 222).

From Translation to Localization

The perception of translation as a word-for-word replacement process has been countered by technical communicators for some time (Batova & Clark, 2015; Sun 2006, 2012; Walton, Zraly, & Mugengana, 2015). Batova and Clark (2015), for example, describe localization – the process of adapting content for a specific culture – as an alternative to the one-to-one translation process. Localization aims to address linguistic and cultural expectations of specific cultures in specific contexts (Batova & Clark, 2015). Hence, localization accounts for not only the replacement of words, but also adapting materials to convey overall meaning from one culture to another. For example, conventional perceptions of translation might involve revising the text of a website to convey the same ideas in a different language. Localization, by contrast, would involve not only the translation of a website's text, but also the potential re-design of the sight to best address the expectations and usage patterns of individuals from another culture.

For the purposes of this paper, we will be using the term “translation” to refer to how individuals who speak more than one language convey the meaning of specific words across languages. That is, while we are using “translation” to mean the attempt to replicate the meaning of a word from one language to another language, we are also accounting for the ways users contextualize words from their heritage languages into English. This process of language contextualization is common in the practices of trained translators. However, we also found that when individuals who speak English as a second or third language attempt to convey concepts from their heritage language in English, they do more than replace one word for another.

Multilinguals also provide descriptions of how these words are used in context across cultures. For example, if a person who speaks English as a second language wants to describe a practice or idea from his or her heritage language in English, she or he might tell stories about how that word is used in context. In so doing, that person might use gestures and voice intonation to describe how this practice or idea can be understood in English. In this way, analyzing the translation practices of multilinguals who are not trained translators or interpreters can provide technical communicators with additional knowledge about the connections between translation and localization. While technical communicators largely understand the importance of translation and localization (Agboka, 2013; Sun, 2006, 2012; Walton, Zraly, & Mugengana, 2015), recent work has also acknowledged the continued need to develop best practices and strategies for effective translation across linguistic and cultural contexts (Bokor, 2011, p. 210).

Toward User-Localized Translation

To better understand how technical communicators can continue developing successful models for translating and localizing content across languages and cultures, we designed a pilot study to examine how multilinguals engage in translation through user-localization. Because multilinguals are fluent speakers of more than one language, they are often accustomed to translating and localizing knowledge across languages and cultures (Agboka, 2013; Sun, 2012). Multilinguals in the U.S., even without professional translation training, are in the practice of making sense across languages as they translate information from English into their heritage languages (and vice versa) in their daily interactions. For this reason, we believe multilinguals hold expertise that can inform how technical communicators think about and approach translation and localization practices.

In our pilot study, we sought to answer the following research question:

What rhetorical strategies do multilinguals use to adapt information from one language to another?

We chose to conduct a pilot study to address this question because we wanted to quickly assess the validity of our assumptions of what translation looks like as it is enacted by multilinguals. A pilot study approach was also useful because we wanted to build a sample set of data by which we could develop preliminary analytical and conceptual tools that could be used (by ourselves and others) in future research. Finally, by beginning to understand how experts in multilingual, cross-cultural communication adapt information across languages, we hoped to identify strategies technical communicators could use to interact more effectively with translators and localizers to generate materials for audiences from various cultures.

Method

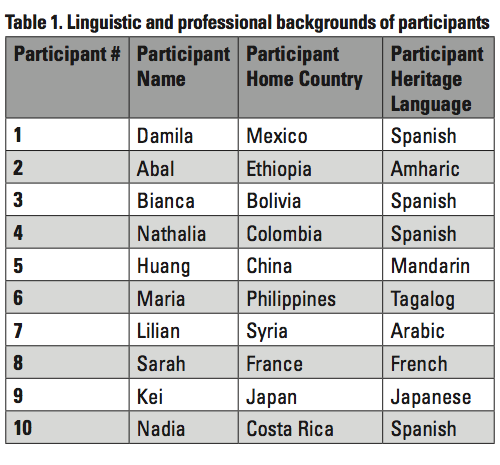

To help us understand how translation and localization are enacted by multilinguals in practice, we conducted IRB-approved, video-recorded interviews (lasting approximately ten minutes each) with ten multilingual students at a Michigan State University (MSU). While the multilingual participants were all students during the time of the interviews, they came from various professional and cultural backgrounds, as shown in Table 1.

Participant Recruitment and Population Sampling

Participants were contacted through the international studies listserv at their university campus. All members of the listserv were contacted via e-mail and invited to participate in interviews associated with this research project. Many of the participants who agreed to be interviewed for this project attended college and worked in their home countries before returning to the U.S. for graduate school. All participants spoke English with enough fluency to complete college-level coursework and were self-reported fluent speakers of English. Additionally, these participants represented eight different home countries (for example, Bolivia, Colombia, Syria, Ethiopia, Japan, China, Mexico, Costa Rica, France, and the Philippines) and eight different heritage languages (for example, Spanish, French, Arabic, Mandarin, Japanese, Amharic, and Tagalog). All participants spoke English as a second or third language, and three of them spoke an additional language aside from English and their heritage language.

Interview Protocol and Sample Questions

Each participant agreed to participate in a ten-minute interview in which the interviewee was asked to identify what they would consider as their first or heritage language. Next, interviewees were presented with a series of open-ended questions about their heritage language and translation practices (see a copy of all interview questions in Appendix A). Specifically, participants were asked “Can you describe a word in your heritage language that is difficult to translate into English? What is the word and what does it mean?” To collect data from these interviews, each session was video recorded and the related recording was later analyzed to look for patterns in individuals' translation practices.

The overarching objective of this pilot study was to better understand how participants re-create meaning from their heritage languages when they translate concepts into English. (These words came from Sanders' (2014) discussion of “11 Untranslatable Words from Other Cultures.”) We asked interviewees to describe a word that they felt did not have an easy one-to-one replacement into English (that is, no one word in English was a direct match to the meaning of a corresponding word in the participant's heritage language). Because none of the words participants selected had an easy one-to-one translation available in English, we were interested in how participants used stories and/or made comparisons to describe terms from their heritage languages in English.

Although participants were aware they would be asked to translate “untranslatable” words in the interview, they were not given a list of words for translation or a detailed script of how the process would take place beforehand. This was because the goal of our research was to capture translation moments as they naturally unfolded, so we wanted to prevent participants from giving rehearsed definitions. As participants attempted to describe the meaning of the words they selected in their heritage languages, they employed several strategies captured on video recordings. These recordings were then analyzed to identify the strategies multilinguals used when translating and localizing information (that is, specific words) from their heritage languages into English.

Analysis

Video recordings of each interview were analyzed using Nvivo. Nvivo is a software program that allows researchers to code video data under various categories. During the analysis phase of the research, we watched and coded all the videos individually, using each sentence uttered by participants as an initial unit of analysis. During this coding process, we first listened to and watched each sentence uttered by participants during their interviews, and then noted a description of the types of strategies (for example, gesturing, storytelling) participants were using to describe words – specifically, words that did not have a one-word-to-one-word correspondent in English – from their heritage languages in English. While we did not start by looking for any specific translation strategies, we paused the video after every sentence to write descriptions of the strategies we saw participants using to translate in that unit. For example, if a participant used her hands during a sentence, we would write “gesture” as an initial code for that unit. If she began to tell a story in a sentence, wrote “storytelling” starting with that unit, until the story concluded. Each of us initially completed this process for all ten videos used in this study.

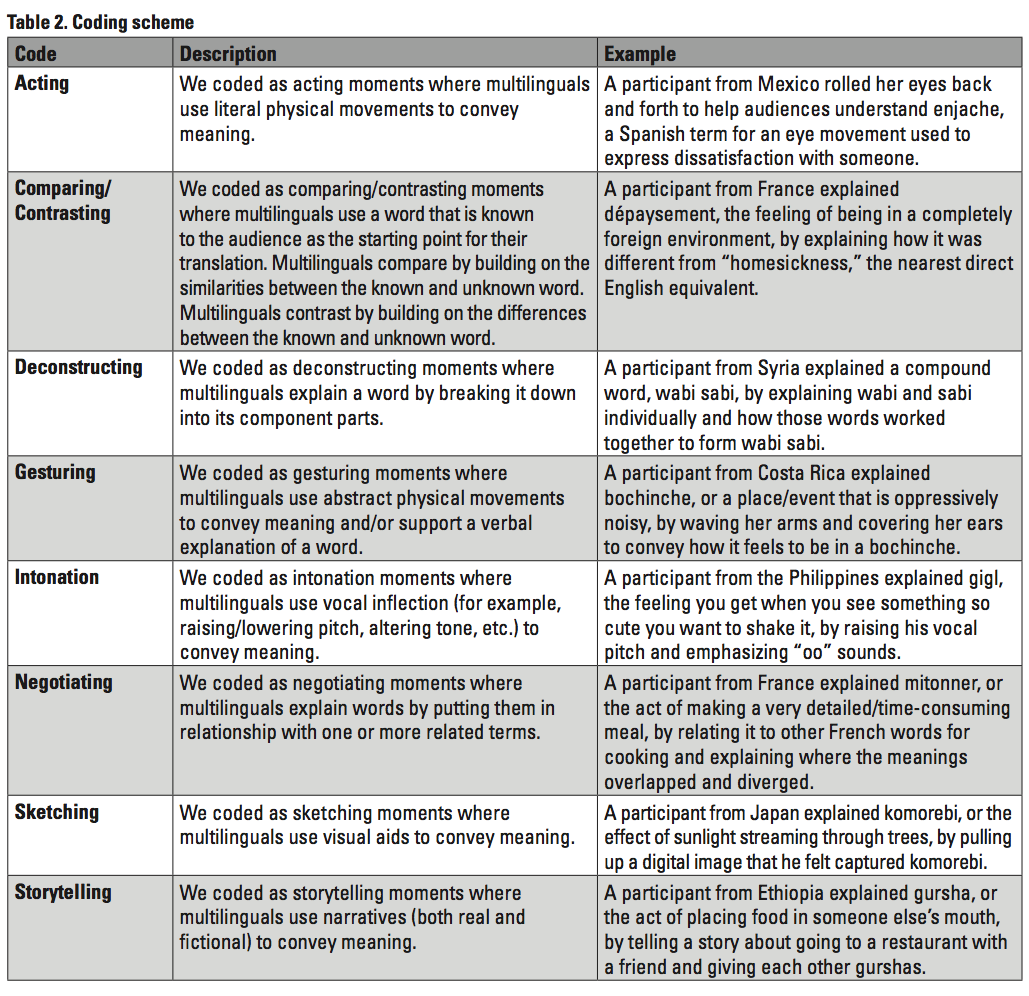

After coding individually, we compared our initial descriptions (for example, “hand gestures”) and developed new coding categories together to represent the triangulated coding scheme. For example, we replaced our initial description of “hand gestures” to the coding category “gesturing,” which we describe in Table 2 as “moments where multilinguals use abstract physical movements to convey meaning and/or support a verbal explanation of a word.” We created all coding categories together, drawing only from what we saw and heard as we coded the video interviews individually.

After developing the revised coding categories illustrated in Table 2, we re-coded the videos together. During this process, we watched each video together on one computer, pausing after each sentence the participants uttered to note the coding categories from Table 2 that applied during that unit of analysis. We then tabulated all code frequencies as illustrated in Table 2.

As illustrated in Table 2, the translation patterns we identified coding participants' video-recorded interviews account for much more than individual word-to-word translation. Instead, our codes account for the ways users localize information as they try to convey meaning from one language to another. Such processes, we found, involve more than just words. Rather, they are undertakings in which the individual uses body language, intonation, and other non-verbal resources to try to convey meaning. In this way, we analyzed how participants “organize, dramatize, reflect upon, and understand” language through their non-verbal communication as well as their verbal utterances (Sauer, 2003, p. 257).

Results

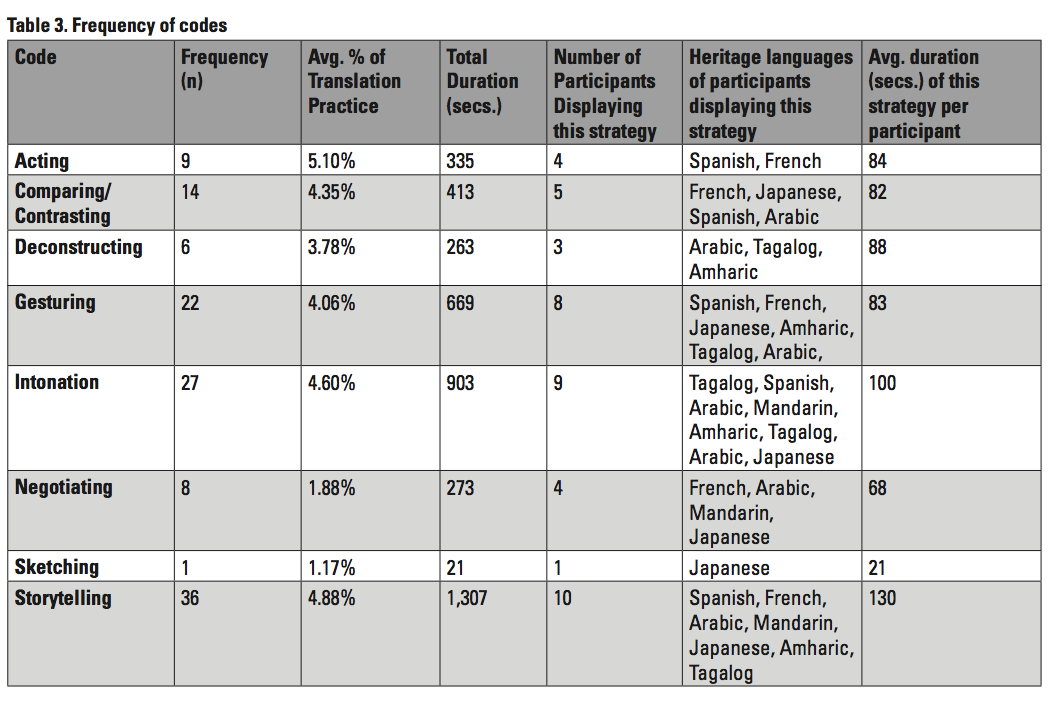

The video interviews resulted in a total of 140:11 minutes of coded video footage (roughly 14 minutes per interviewee). Results illustrate that participants spent a total of 69:43 minutes (roughly 7 minutes per interviewee) in what we describe as “translation moments,” or instances when participants were translating and localizing language using the strategies coded in Table 2.

As Table 3 illustrates, the strategy yielding the longest duration within translation moments was storytelling (that is, where multilinguals use narratives — both real and fictional — to convey meaning). Storytelling was a behavior displayed by all participants at some point during their interview, and it happened a total of 36 times and occupied of 21:46 minutes of video footage across all participants.

While the translation strategies we describe in Table 2 were employed to some degree by multiple participants (with only one strategy — sketching– only employed by one participant), our analysis suggests individual participants combined and further localized these strategies to meet their individual translation goals during their interviews.

As Table 3 demonstrates, all participants used more than one strategy to describe words from their heritage languages into English, with the frequency of each code ranging from 1 to 36 occurrences for all participants. Each strategy listed in Table 3 also lasted from a range of 21-130 seconds on average for each participant.

In the following sections, we outline three individual participants' “translation moments” in an effort to further contextualize how translation is a user-localized practice. Through these examples, we aim to illustrate how participants layer translation strategies to convey meaning across languages.

Case Study 1 Sarah: Telling Stories to Contextualize Meaning

“Sarah's” first language is a Parisian dialect of French. During her interview (which lasted approximately 30 minutes), Sarah translated four words from French into English. During these translation moments, Sarah relied primarily on storytelling— in combination with other strategies such as intonation and gesturing— to convey meaning to her audience. Moreover, storytelling accounted for 5:50 minutes of Sarah's translation practices and occurred 9 distinct times throughout her interview. Sarah used storytelling to translate all four of the “difficult to translate” words from French into English.

The first time Sarah used storytelling was to describe affriolant, a French adjective that is used to describe a person who is a classy form of sexy (as opposed to non-classy or raunchy forms of sexy). After offering a preliminary definition of affriolant, Sarah moved into describing the type of person who would be characterized as affriolant. Sarah was not asked to further describe the term she was translating; however, she offered the following description of affriolant on her own:

She is a woman who is noticeable, she is very feminine— maybe almost a bit too much, she attracts the eyes.

Throughout her story, Sarah incorporated gesturing and intonation strategies to impersonate an affriolant woman.

Another time Sarah used storytelling occurred when she described ballot, a word that has two connotative (that is, socially based) meanings. To explain the differences between these two meanings, Sarah tells two stories back-to-back. The first was used to explain what ballot means when referring to a situation. A ballot situation, roughly translated, is an event that was going well until one disastrous moment.. Sarah explained a ballot situation via this following story:

You and all your friends are so excited, you're going to go to this party and everybody is ready and you're about to get in the car and you go to start the car and there's no gas. And then you'll be like, ‘Ohh, [French words] ballot. This sucks.

When Sarah reached the point of her story where she talks about running out of gas, she used a shrugging gesture to emphasize the future futility of the situation and the “Oh, well” feeling a ballot situation creates.

However, the meaning of ballot changes when it refers to a person. Thus, immediately following her story about a ballot situation, Sarah tells a story to describe a ballot person. Sarah's story carries on the party metaphor and talks about how a ballot person is good-natured, but always makes clumsy mistakes that ruin the party. Again, Sarah's story is combined with intonation and facial gestures to convey the feeling a person may have toward a ballot individual.

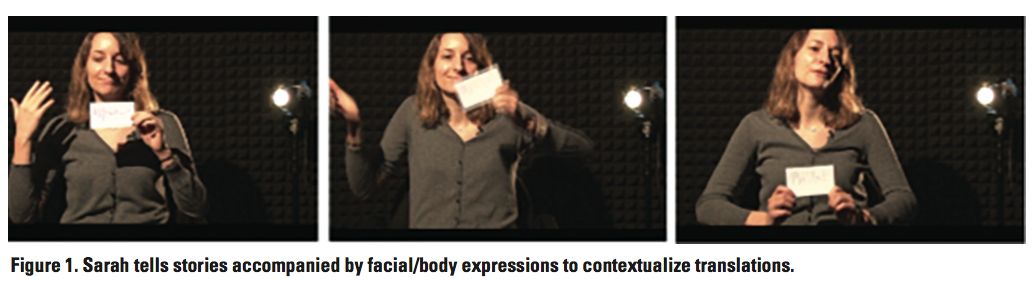

Figure 1 demonstrates Sarah's facial expressions and gestures during storytelling for translation. The first image captures the gestures Sarah used when telling the story of an affriolant woman, the second captures her gestures for describing a ballot situation, and the third captures her facial expressions during her story of a ballot person.

What Sarah's use of a storytelling strategy shows is that translation— as it is localized by multilinguals — is about more than word replacement. For every word Sarah translated, she accompanied her descriptions of the word with stories. This process illustrates how Sarah sees meaning as embodied in specific contexts of use. In essence, Sarah draws from her experiences as a dual member of French-American society more than her knowledge of vocabulary to provide definitions as word pictures. Sarah's focus in these translation moments is more centered on conveying the emotional experience of affriolant and ballot than on providing adequate one-to-one replacement words in English. In so doing, Sarah is localizing the ideas of affriolant and ballot to her English-speaking audience through the narration of contextual experiences.

Case Study 2 Damila: Combining Strategies to Localize Translation

“Damila” is from Mexico, and her heritage language is Spanish. During her interview, Damila was asked to translate the Spanish phrase sobre mesa, which translates to English as “above the table.” When describing sobre mesa, Damila first provided a literal translation of the phrase sobre mesa by explaining that the phrase means “above the table.” However, without being prompted, Damila further explained that this literal translation of the phrase in her heritage language is not accurate. Instead, Damila localized sobre mesa by employing several coding strategies simultaneously: comparing, gesturing, and intonation-inflection. During her 10-minute interview, Damila spent 8:32 minutes translating sobre mesa by combining strategies.

Damila started to elaborate on the literal translation of sobre mesa by comparing the phrase to common dining practices in the United States. She explained,

We have a word to use after you finish eating lunch or dinner. If you stay at the table after having the meal we call it sobre mesa. Probably we use it because, for example here you eat lunch and that's it. In Mexico is like ok the dessert, the coffee, and we added a word for that which is sobre mesa.

Damila compared the phrase sobre mesa to common dining practices in the United States by saying, “for example here you eat lunch and that's it…” As she spoke, Damila began to make circular gestures with her hands to indicate the extended dining process that takes place in Mexico as people have “the dessert, the coffee” and so on.

As Figure 2 illustrates, Damila combined her comparison of dining practices with her use of gestures, illustrating just how extended the practice of sobre mesa is for her family in Mexico. Her gestures suggest the dining experience in Mexico can often “go on and on,” which is how the phrase sobre mesa emerged.

In addition to defining the phrase sobre mesa through a combination of gestures and comparisons, Damila further localized the phrase by explaining that the term is only used in certain parts of Mexico. When the interviewer asked, “So there are particular phrases only used in certain parts of Mexico?” Damila elaborated by explaining that the language practices in Mexico are very closely tied to geographic regions. She explained

In Mexico, if you go to the north, center, or south, we can very easily notice where you're from since we sing sometimes when we're talking.

Damila went on to explain the different ways the phrase sobre mesa could be said in various parts of Mexico. She used tone inflections to signify how speakers from different regions of Mexico would utter the same phrase. At the same time, Damila also used her hands to visually indicate the differences between these phrasings, explaining that some speakers may cut their words short while others may elongate their vowels. Figure 3 illustrates the gestures Damila used in combination with her tone inflections to describe how speakers from various parts of Mexico may use and pronounce the phrase sobre mesa.

As Damila's discussion of sobre mesa suggests, when users localize translation practices to meet their needs, they often employ several translation strategies simultaneously. For Damila, simply translating sobre mesa to “above the table” would not encapsulate the cultural implications embedded in the phrase as it is used in Mexico. Furthermore, as Damila illustrated, conveying meaning across languages often requires attention to semiotic resources like tone and body language.

Case Study 3 Kei: Sequencing Translation Strategies Based on Audience Response

“Kei” who identified his heritage language as Japanese, attempted to translate the term komorebi, a Japanese word that (roughly) means the interplay between light and leaves when sunlight streams through trees. Kei's translation time for this word had a duration of two minutes and 24 seconds. He translated a total of 3 words during his 12-minute interview, and in doing so, he used sequenced translation strategies (gestures, sketching, and deconstructing) for his translation events. Additionally, Kei used gestures and sketching (that is, physical movements and drawings) for all three translation events, but he only used deconstructing (that is, breaking down a word into all its components and parts) to translate komorebi.

During Kei's translation event, he employed three unique strategies in sequence to provide alternative, more nuanced explanations of komorebi. What is interesting about Kei's translation strategies is that instead of using layered strategies (that is, using multiple strategies at once), Kei used sequenced strategies. That is, Kei would rely on one strategy at a time to translate komorebi to an English-speaking audience.

First, Kei used gestures when trying to translate the term. He noted, “Komorebi means sunlight streaming through trees” while using his right hand to imitate sunlight (for example, spreads his fingers apart with palm downward and arm over his shoulder) and how the light disperses through trees (for example, moving his hand back and forth at shoulder level while still making the sun gesture). Kei then moved from gesturing to sketching. Using a tablet computer he had brought with him, Kei pulled up a picture that he felt illustrated komorebi and then turned the tablet toward his audience while saying “This, this sunbeam is komorebi” and pointing at a beam of light shining through trees with his right index finger.

After the interviewer voiced some confusion about her understanding of komorebi, Kei adopted a third strategy— deconstructing —to translate komorebi. Kei split the word into its three component parts— tree, leaking, and sunlight — and then explained the definition again using these component words. During deconstruction, Kei also used gestures to number off the component parts (that is, holding up one finger for the first component part, two fingers for the second, and three for the third). Based on positive feedback from the interviewer (“That makes perfect sense!”), Kei ended his translation moment. Figure 4 shows screen captures of Kei's three translation strategies. The first two illustrate his gesturing moves, the third his sketching moves, and the fourth his deconstruction moves.

What's interesting about Kei's translation practices is not only the various strategies he leveraged to communicate with his audience, but also the way he sequenced physical, visual, and logical descriptions of komorebi based on explicit and perceived feedback from his audience. Kei began with a physical description, enacting komorebi through gestures. While he was completing these gestures, he made eye contact with the interviewer, trying to determine via her facial reactions if the meaning of komorebi was clear. Feeling dissatisfied with her response, Kei switched to a visual description and used an image on his tablet computer to enhance his description. Although the interviewer reacted positively to Kei's visual description, a question she asked reflected a less-than-complete understanding of komorebi. Therefore, Kei moved into his logical description of komorebi. Kei's translation event only ended after the interviewer gave explicit feedback that she understood Kei's explanation.

It's interesting to note that while Kei used gesturing and sketching to define all three terms he translated during his interview, the interviewer's confusion led him to employ a third strategy (deconstructing) to describe komorebi. In fact, as evidenced in Table 3, deconstructing is the only strategy exclusively used by a single participant. This factor perhaps suggests that multilinguals resort to new and different translation strategies based on feedback from their audience.

Because the interviewer did not experience confusion during other interviews, perhaps it was this confusion that led to the use of a new and unique translation strategy (deconstructing). While this argument would certainly need further analysis, it was interesting to see how the translation strategy of deconstructing emerged from the interviewer's confusion during a translation moment. Kei's adaptation and implementation of deconstruction is a purposeful rhetorical strategy used to further localize a word from Japanese into English.

Kei's interplay with the interviewer and his adjustment of translation strategies based on audience feedback classifies his translation work as rhetorical practice. Whereas contemporary discussions of translation typically position translation communication as non-rhetorical, Kei's production of iterative translation strategies based on audience awareness is a rhetorical act of invention (which we define as the discovery of arguments). Kei's invention is happening on-the-fly as he processes verbal and nonverbal cues of (mis)understanding from his interviewer. This demonstrates the intellectual labor of translation work and the way a single translation can be conveyed rhetorically via different strategies for different purposes.

Discussion

Our analysis of users' localized translation practices suggests there are several elements to translation that are not always accounted for when technical communicators think about translating materials to convey information to audiences from various cultures.

First, our research demonstrates user localization of translation practices are accomplished via multiple, layered, and sequenced strategies. While some of these strategies— like storytelling and gesturing — are not necessarily new, the purposeful, rhetorical use and layering of these strategies (as illustrated through our case studies) exemplify the complex negotiation of history, culture, and language that takes place as users translate words and phrases into English. This intellectual complexity and rhetorical implication is often not recognized in current discussions of translation in technical communication, where the tendency is to think in terms of word-to-word replacement. In this model, all of the credited intellectual labor is done by the individual(s) writing the original language version and the translators of the content are positioned as mere processing agents (which, in the case of machine translation, is quite literal). Our research suggests that technical communicators need to re-consider how they conceptualize translation work and, by extension, the people who do that work.

Second, our research demonstrates user localized translation is a sequenced, scaffolded response to audiences. For the participants we interviewed, the translation and localization strategies employed largely relied on the reaction participants were receiving from their audience (that is, the interviewer). If the interviewer confirmed a definition provided by the participant, the participant might elaborate through a new story or example to further develop meaning. If the interviewer incorrectly described the term being translated by the participant, however, that participant would choose to layer, sketch, or act out the term further. In this way, multilinguals exhibited a nuanced rhetorical dexterity as they adjusted their translation strategies to meet the needs of their audience at a specific time. Popular discussions of translation in technical communication sometimes present translation as a “one-and-done” event (that is, a quick replacement of words), one that often occurs at the end of a writing/design project. Our research challenges this perception and argues that culturally-sensitive, global-ready translated content needs to be iterative, sequenced, and responsive to effectively localize meaning across languages.

Additionally, our research positions translation as an experience-centric event. Participants in our study drew upon their own experiences and cultural knowledge to localize translations in context. Sarah, Damila, and Kei called upon a wide array of experiences to transform the meaning of words from their first languages into English. By explaining words in their contexts of use, participants revealed the benefits of cultural knowledge to the translation process and the usefulness of story to illuminate meaning. This finding stands in contrast to one-to-one input/output models of translation that are focused on pragmatic goals of efficiency and accuracy. Thus, our analysis argues for an experiential— instead of merely utilitarian — perspective on translation.

As technical communicators and practitioners working toward creating user-centered global content, it's important that we consider not only the words we are transforming through localization, but also the experiences, stories, and histories we are referencing and recreating as we move information across languages. Technical communicators creating content in English for international audiences could consider further researching and implementing contextualized uses of language (such as stories) in international content.

Applications of Research

Drawing from our analysis of translation as a user-localization practice, we offer the following suggestions and implications for technical communicators working in increasingly global contexts:

- Individuals who translate content work as builders and contributors of knowledge, not as simple replacement agents. Our preliminary study suggests translation is difficult intellectual work that requires significant adaptation and recontextualization of culturalized knowledge. As Walton, Zraly, and Mugengana (2015) also explain, “translators always shape data in cross-language research,” and must be acknowledged as active participants in technical communication research and practice. We also make an argument for the value of multilinguals who are not professional translators or interpreters in cross-cultural research, as these individuals have learned translation strategies in practice that can be useful to researchers, designers, developers, and technical communicators.

- When planning a project, technical communication researchers and practitioners should plan for iterative and responsive translation versioning instead of a “one-and-done” translation. As illustrated through Kei's responsive translation based on feedback from the interviewer, accurate translation often requires the implementation of inventive, responsive translation strategies developed in the moment of translation. For this reason, translation should be a practice situated within the development stages of any product or document intended for multilingual audiences, thus allowing for audience response and feedback.

- Technical communicators and information architects could benefit from conducting usability tests with translated, as well as first language, versions of a product/site. All of our participants demonstrated intricate, multi-layered understandings of words in their heritage languages. Often, simple literal translations did not adequately account for the ways language is culturalized and used by multilingual participants (see, for example, Damila's discussion of sobre mesa). For this reason, it's important to conduct usability tests during and after the translation process for any system or document to both account for and value the culturalized linguistic knowledge and needs of international users.

- Multilingual participants can teach us how to translate rhetorically. As evidenced in the layered, rhetorical translation strategies exhibited by our participants, multilinguals have expertise in adapting knowledge and information across languages and cultures. Often, individuals who speak English as a second or third language are positioned as inferior in U.S. academic and professional settings. Our findings suggest that these individuals, rather than taking deficit positions in these contexts, could be consulted as rhetorical experts who can transform knowledge to meet the needs of culturally diverse audiences, even if these individuals do not have professional training in translation. Multilingual users reflect the increasingly diverse audiences of technical documents and technologies, and should therefore be acknowledged as expert participants in the development process.

Limitations

We strategically employed a pilot approach for this study to

- Validate deeper research assumptions

- Build preliminary research frameworks (for example, a coding tool) that can be used by us and other technical communication scholars for future inquiry

Due to the small number of participants represented in this study, the findings we present are preliminary and non-generalizable. However, while the number of participants represented is small, we attempted to include a broad range of languages in our sample, allowing us to see how translation is enacted by speakers from different cultures with different heritage languages.

While our preliminary findings are useful, more extensive studies could expand upon and test our initial findings with a larger group of individuals or with large sample groups in specific cultures and languages. For example, we noted some similarities in the translation strategies used by four Spanish-speaking participants, with all four participants using gesturing and storytelling to translate. However, since these four Spanish-speaking participants came from different countries and spoke different dialects of Spanish, we cannot make generalizations about the patterns exhibited in the translation practices of Spanish speakers. Future studies could more intricately trace if and how participants' heritage languages lead to any consistent patterns in translation strategies.

Future research in this area would also be useful in terms of identifying additional translation strategies that may not have been visible in this study and in tracing how those translation strategies evolve and interact over time. Specifically, we are already using the early analytical tools developed in this study to examine how a group of multilingual writers work to translate content over a period of time. In so doing, we hope to see how strategies are used by multilinguals situationally and how group dynamics impact translation practice.

Conclusion

Analyzing user-localized translation as an activity has helped us understand translation as a purposeful, intellectual process. Individuals who move across languages to communicate their ideas draw on a wide arrange of semiotic resources, and they layer and sequence these resources rhetorically to meet the needs of their audiences.

The main argument of this article is that translation work, much like early technical communication, is an under-theorized and under-rated intellectual practice within the field of technical communication — one that deserves more careful scrutiny by the technical communication community. To this end, we provide thick descriptions (that is, layered and culturally-situated illustrations) of translation in context to highlight the complexity of translation as intellectual work. We offer these descriptions to re-cast translation as a complex, intellectual activity.

This new framework for theorizing and enacting translation can prompt conversations about the role of human translators in technical communication work and/or how the design of machine translation tools can be improved by understanding what user localized translation looks like in context. Analyzing the translation practices of individuals who have heritage languages other than English helped us understand how technical communicators creating content in English for international audiences could expand their conceptions of translation to account for cultural context. Additionally, analyzing the translation practices of our participants helped us understand how translation work extends beyond the written and verbal; technical communicators creating content for international audiences could in turn continue making use of visuals and other semiotic resources to transform content across languages.

Finally, we suggest that further research is necessary to better understand how multilinguals can inform technical communication research, teaching, and practice. In this way, we can continue to develop “more research and teaching approaches that historicize technical communication's roles in hegemonic power relations” by pushing for methodologies that break from expert/non-expert dichotomies in multilingual content development and design (Scott, Longo, & Wills, 2006, p.1).

References

Agboka, G. Y. (2013). Participatory localization: A social justice approach to navigating unenfranchised/disenfranchised cultural sites. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22(1), 28-49.

Batova, T., & Clark, D. (2015). The complexities of globalized content management. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 29(2), 221-235.

Bolarsky, C. (1995). The relationship between cultural and rhetorical conventions: Engaging in international communication. Technical Communication, 4(3), 245-259.

Jarvis, M., & Bokor, K. (2011). Connecting with the “Other” in technical communication: World Englishes and ethos transformation of U.S. native English-speaking students. Technical Communication Quarterly, 20(2), 208-237.

Maylath, B., Vandepitte, S., Minacori, P., Isohella, S., Mousten, B., & Humbley, J. (2013). Managing complexity: A technical communication translation case study in multilateral international collaboration. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22(1), 67-84.

Amant, K. S. (2002). When cultures and computers collide: Rethinking computer-mediated communication according to international and intercultural communication expectations. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 16(2), 196-214.

Sanders, E. F. (2014). 11 untranslatable words from other cultures. DISQUS, Retrieved from http://blog.maptia.com/posts/untranslatable-words-from-other-cultures

Sun, H. (2006). The triumph of users: Achieving cultural usability goals with user localization. Technical Communication Quarterly, 15(4), 457–481.

Sun, H. (2012). Cross-cultural technology design: Creating culture-sensitive technology for local users. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Torrez, J. (2013). Somos mexicanos y hablamos mexicano aqui: Rural farmworker families' struggles to maintain cultural and linguistic identity in Michigan. Journal of Language, Identity and Education, 12(4), 277‐294.

Walton, R., Zraly, M., & Mugengana, J. P. (2015). Values and validity: Navigating messiness in a community-based research project in Rwanda. Technical Communication Quarterly, 24(1), 45-69.

Sauer, B. (2003). The rhetoric of risk: Technical documentation in hazardous environments. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Scott, J. B., Longo, B., & Wills, K. V. (2006). Critical power tools: Technical communication and cultural studies. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

About the Authors

Laura Gonzales is a PhD candidate and Distinguished University Fellow at Michigan State University, where she studies and teaches digital rhetoric and professional writing. Her research focuses on highlighting the affordances of linguistic diversity in professional and academic spaces. Her work has recently appeared in Composition Forum and the Journal of Usability Studies. She has been recognized as a Scholar for the Dream by the Conference on College Composition and Communication, received the inaugural Hawisher and Selfe Caring for the Future Award sponsored by the Computers and Writing Conference, and the 2014 Diversity Award sponsored by the Council of Programs in Technical and Scientific Communication. She is available at gonzlaur@gmail.com.

Rebecca Zantjer is a User Experience Researcher at Owens Corning. She recently completed her MA in Digital Rhetoric and Professional Writing and User Experience Internship at Michigan State University. Her work looks at the ways technology can be made accessible and usable to inclusive populations, with a special focus on building technologies to support writing pedagogy. She is available at rzantjer@gmail.com

Manuscript received: 20 April 2015; revised: 19 September 2015; accepted: 20 September 2015.

Appendix A: Interview Questions

- Can you tell us what you identify as your first or heritage language? What is the first language you learned to speak?

- We asked you to join us today to talk about words in your heritage language that you think might be difficult to translate into English. Can you think of any words in your heritage language that can't be easily translated into English?

- Can you choose one of the words you described in your answer to the previous question and try to translate this word into English? What is the word and what does it mean?

- Why do you think this word is difficult to translate into English?

- Can you choose another word from your answer to question 2 and attempt to translate it into English? What is the word and what does it mean?

- Are there other words in your heritage language that you think might be difficult to translate into English? How would you attempt to translate these words?

Footnote: Drawing from the work of Torrez (2013), we use the term “heritage” language instead of “native” or “first” language to reference the language our participants identified as most significant in their linguistic development. The term heritage language aims to credit the cultural context of linguistic development.