By Eric Sentell

Abstract

Purpose: This paper presents results from a primary study investigating the qualities of memorable documents and extrapolates principles for making documents more memorable, and thus more effective, for audiences.

Method: I asked twenty subjects to walk down a high school hallway decorated with flyers and posters. I interviewed them immediately afterward and one week later to determine which information “stuck” over time as well as the subjects’ self-reported reasons for recalling information. I then analyzed the most-often remembered documents to correlate the subjects’ responses to the documents’ content, design, style, etc.

Results: Contrast, color, and imagery are inherently attention-catching and memorable. However, engaging the audience’s collective self-schema, or identity, impacts memory even more powerfully by prompting readers to ascribe relevance to information and thus strive to remember it. Accordingly, I propose the following heuristic for creating more effective, mnemonic documents: (a) convey practical value; (b) use contrast, color, and imagery; (c) tap the familiar; (d) introduce unexpected elements; (e) build social currency; and (f) arouse emotion.

Conclusion: Technical communicators can enhance their documents’ effectiveness by using the proposed heuristic to make information more memorable for their readers.

Keywords: attention, memory, schema, audience, design

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Documents influence readers’ memories through their design and content.

- Contrast, color, and imagery are inherently attention-catching; thus, they can make information more memorable.

- Engaging the audience’s collective self-schema, or identity, prompts the audience to ascribe relevance to information and thus strive to encode it into long-term memory.

- The following strategies can catch attention and engage readers’ self-schema: (a) convey practical value; (b) use contrast, color, and imagery; (c) tap the familiar; (d) introduce unexpected elements; (e) build social currency; and (f) arouse emotion.

Introduction

In technical communication, discussions of memory usually explore managing one’s composing, research, or reading processes (van Ittersum, 2007, 2009; Whittemore, 2008, 2015). However, memory can also be viewed as a trait of documents. Numerous eye-tracking studies have observed a positive relationship between attention and recall (Lee & Ahn, 2012), because a person must pay attention to information to encode it into long-term memory for later retrieval (Nairne, 2011). It follows that writers can impact readers’ memories by presenting information in ways that facilitate effective encoding. As Richard Lanham (1993) puts it, rhetoric “allocates emphasis and attention” (p. 61).

Lanham (2007) also points out that human attention is the primary commodity and scarcity in a knowledge-based economy, and thus it “should not surprise us that the dominant discipline . . . is [now] design” (p. 17). Information can be present in a document yet likely excluded from the reader’s recollection due to poor or unethical design (Allen, 1996; Kostelnick, 1996). Since design manipulates attention and attention enables memory, document design is essential to memorable communication. And memorableness is increasingly essential in our information-saturated world; readers must recall information to be able to use it. Standing out does little good if the audience merely notices and does not encode or remember.

To learn how to improve a document’s memorableness, I investigated the following research questions:

- What design elements cause a reader to attend to information in such a way that he or she will remember that information?

- How do these design elements enhance a document’s memorableness?

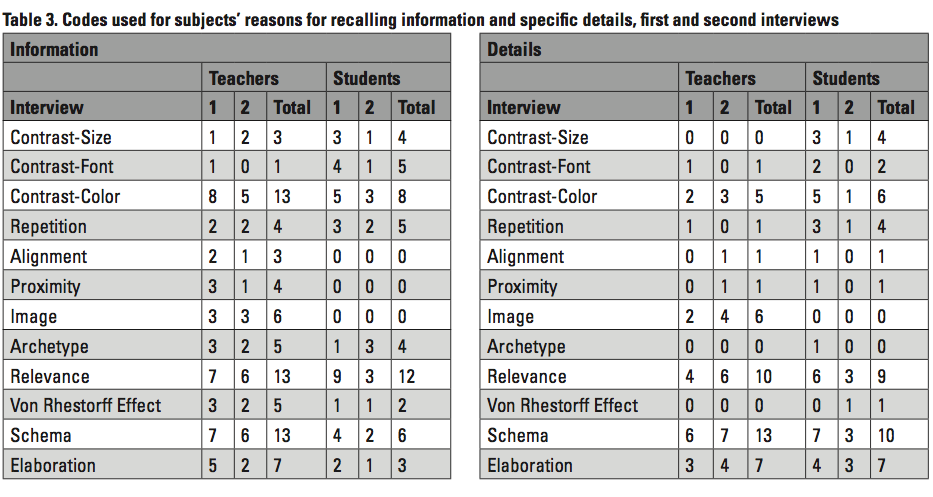

I interviewed twenty subjects about their recollections from various posters and flyers, their reasons for remembering this information, and the likelihood that they might apply it. One week later, I conducted a follow-up interview to determine which information “stuck” and why. I coded the subjects’ interview responses with common design and psychological terms.

The subjects’ memories were consistent from the first to the second interview, indicating that documents influence long-term memory. Certain posters and flyers were remembered much more often than others, demonstrating that rhetorical and design strategies affect documents’ memorableness. When asked why they recalled certain documents, the subjects often cited contrast, color, and/or imagery. Contrast, color, and imagery are inherently distinctive and attention-catching, thus increasing the chances of information conveyed through them being remembered.

While design influenced subjects’ attention and memories, the subjects’ self-schema were even more influential. Self-schema, or conceptual frameworks about oneself, affect a person’s judgment of relevance (Markus, 1977). That is, people tend to view information as personally relevant if it fits their sense of self or identity. Certain groups have similar self-schema as a result of belonging to the same discourse community (Porter, 1986). My subjects often referred to the (ir)relevance of documents, and they seemed to judge (ir)relevance based on their self-schema. Thus, writers and designers should engage readers’ collective self-schema so that readers ascribe relevance to information and endeavor to encode it. The following heuristic lists the design and rhetorical strategies that seem to effectively engage audiences’ self-schema: (a) convey practical value; (b) use contrast, color, and imagery; (c) tap the familiar; (d) introduce unexpected elements; (e) build social currency; and (f) arouse emotion.

Traditional heuristics for communication include criteria such as accuracy, brevity, clarity, and achieving the reader’s goals (Dragga & Voss, 2001). These qualities are rightfully valued as markers of a text’s efficiency and effectiveness. But I argue that communication is more effective and powerful if the reader can easily remember it, and thus technical communicators can benefit from a heuristic for composing and designing more memorable documents. A reader can often refer back to a text, of course, but then the document’s usability becomes an issue (Manning & Amare, 2006). Moreover, long-term memory contains the experiences that form our identities and attitudes, that make us who we are, and therefore it is a more influential rhetorical site and medium than short-term memory (i.e., relying on referencing a text). The research and heuristic described in this paper will help technical communicators work within the site and medium of memory, enhancing their effectiveness as communicators.

Literature Review

Memory in technical communication

Usability studies often address memory, or “memorability,” but these studies tend to focus on users’ memory practices rather than texts’ memorableness (see Nielsen, 1999). Similarly, the most developed technical communication scholarship on memory describes how writers manage their research and writing processes to “off-load” or “embody” both cognition and memory, but this scholarship does not address the qualities of documents that make information memorable. Other scholarship discusses memorable visual rhetoric, yet it does not fully explore how to engage readers’ memories through visual and written means.

In Rhetorical memory: A study of technical communication and information management, Stewart Whittemore (2015) uses a case study approach to analyze six technical communicators’ information management practices. He argues that developing writing expertise involves a process of cultivating social and embodied habit, defined as a memory stocked with shared, collective knowledge that can be drawn upon when needed. This book is a significant step in the study of memory in technical communication, but it focuses on writers’ memory practices rather than documents’ memorableness.

Whittemore and Derek van Ittersum have each published journal articles dealing with memory. Whittemore (2008) critiques the interfaces of content-management systems (CMSs) for not enabling sufficient tracking of metadata, thus overloading technical communicators’ memories. He argues that CMSs should visualize content and context (through print preview, highlighting, or annotating functions) to reduce writers’ cognitive loads. Derek van Ittersum (2007, 2009) explains how graduate students use digital writing tools such as Endnote or OneNote to create organized, searchable memory systems. Their positive and negative experiences illustrate the complexity of developing digital composing and memory practices. These authors ground their research in classical memoria, particularly the architectural mnemonic in which orators mentally visualized information as distinctive symbols placed in familiar settings (Carruthers, 2008; Yates, 1966). They also focus on how writers manage their composing and research rather than the characteristics of memorable documents.

The remaining technical communication articles on memory focus on visual rhetoric. A.S.C. Ehrenberg (2000) describes memorable graphs as simple, minimalist, and clear, with depictions and captions that reinforce each other’s content. John McNair (1996) describes how to design more memorable computer icons by setting vivid symbolic images against contrasting backgrounds. Brian Regan (1998) found that asymmetrical or irregular layouts may be more memorable due to a natural distinctiveness that facilitates encoding. Lastly, Michelle Borkin et al. (2013) showed subjects a stream of visuals (graphs, pictures, etc.) and asked them to indicate when they noticed repeated images. The memorable visuals used more color, contrast, uniqueness, and natural-looking characteristics, but this study measured only recognition, not comprehension or retention. Taken together, these publications suggest the power of contrast for engaging memory. However, they do not explore the rhetorical possibilities and pitfalls afforded by the nature of human memory.

Reconstructive memory, schema, and self-schema

Most scientific fields view memory as reconstructive and mutable, in contrast to previous conceptions of memory as data storage (Francoz, 1999; Braun-LaTour, Braun-LaTour, Pickrell, & Loftus, 2004). Rather than merely a record-keeping and data-storing function memory is a dynamic, socially situated process of reconstructing previous events and stimuli. Our reconstructions can morph over time and can be influenced by new information without our conscious awareness. Therefore, reconstructive memory is both a site and a medium of discourse, persuasion, and power.

In his seminal Remembering, Sir Frederic Bartlett (1932) first described memory as reconstructive. He recounts several experiments in which he asked subjects to recreate a story, picture, or other stimulus from memory. Invariably, the subjects reconstructed the stimuli rather than reproducing it, excluding, modifying, fixating on, or even fabricating various details. Reconstructive memory resembles imagination, but Bartlett distinguishes between pure imagination and “imaginative reconstruction” based on the scope and emphasis of one’s cognition (p. 214). According to Bartlett, reconstructive memory focuses on specific events or details while pure imagination ranges freely among settings and interests (p. 313). Furthermore, his subjects reinterpreted various details without realizing it; usually, they insisted their version was exactly what they had originally perceived.

After Bartlett, Elizabeth Loftus is the preeminent psychological researcher on memory. One of her experiments (Loftus & Palmer, 1974) observed a significant difference in subjects’ speed-estimates of cars involved in an accident when the interviewer used the word “smashed” instead of “hit.” Another experiment (Braun-LaTour, Braun-LaTour, Pickrell, & Loftus, 2004) used misinformation to induce false memories of an impossible meeting with the Warner Bros. character Bugs Bunny on a childhood trip to Disneyland. These misinformation studies show that our perceptions of events sometimes merge with information learned afterward, leading to a reconstructed memory so unified we cannot distinguish which information came from which source (Loftus & Palmer, 1974; Loftus, 1997, 2005). Reconstructive memory can both facilitate and impede communication.

When we reconstruct memories, we usually recall the relevant schema, or conceptual frameworks, that help structure our perceptions and recollections. If we alter our schema to incorporate new information, then we encode that information into long-term memory. Socio-cultural background can affect this process; Bartlett’s (1932) subjects embellished, added, or deleted details based on their socio-cultural subjectivities (p. 87). For example, American subjects did not have to significantly alter existing schema for Disneyland to incorporate Bugs Bunny (Braun-LaTour, Braun-LaTour, Pickrell, & Loftus, 2004), but they might have had more difficulty incorporating dissimilar or unfamiliar misinformation. Since schema function like adaptable heuristics for organizing new information in relation to prior knowledge, it follows that writers need awareness of readers’ potential schema (looking to the readers’ socio-cultural background for clues) and should attempt to induce readers to incorporate new information into their existing schema.

Psychologists widely recognize that a person’s various identities (e.g., husband, father, teacher) combine to form a “social self-schemata,” or a unique memory structure, that influences behavior and cognition (Forehand, Deshpande, & Reed, 2002, p. 1086). In other words, self-schema are conceptual frameworks about oneself. In a seminal article, Hazel Markus (1977) found that self-schema “function as selective mechanisms which determine whether information is attended to, how it is structured, how much importance is attached to it, and what happens to it” (p. 64). While schema organize known and incoming information, self-schema act like filters for one’s attention by screening irrelevant stimuli and highlighting relevant information. This process seems to be mostly unconscious; we may be aware that certain stimuli interest us more than others, but we do not consciously decide whether stimuli match our self-schema.

Document design

Design is important to memorable communication because it can direct readers’ attention and emphasize or underplay ideas (Kostelnick, 1996). Emphasizing certain information over other material can affect readers’ interpretations (Kostelnick & Roberts, 2011), which may then affect their reconstructions. Thus, design is essential to producing memorable documents, since it can substantially influence what we attend to, how we attend to it, and how we recall it later. Common design principles can be used as starting points for both assessing documents’ memorableness and creating memorable documents.

The design principles most commonly taught and practiced include contrast, repetition, alignment, proximity, similarity, order, enclosure, and balance (Johnson-Sheehan, 2012; Williams, 2008). These principles are most effective when used in tandem, creating a “visual hierarchy” that “preprocesses” the document’s content so it can be understood quickly and easily (Krug, 2006, p. 31). If these elements are used together effectively, they create clear, user-friendly layouts for information. It then stands to reason that easily understood documents should be easier to encode and recall. The principle of contrast is especially important to memory since it attracts and directs attention by exploiting the tendency to notice distinctive elements (Baker, 2006; Jones, 1997; Williams, 2008).

Font and color can also affect memory. Readers perceive fonts as having distinct personalities, making type an important design and rhetorical consideration (Holst-Larkin, 2006; Vance, 1996; Brumberger, 2003a, 2003b). Type influences perceptions of a document’s ethos, and varying fonts can create attention-catching contrast and reveal clues about a document’s structure and purpose, clarifying its layout (Johnson-Sheehan, 2012; Brumberger, 2003a, 2003b). Well-used color makes information more eye-catching and appealing (Jones, 1997) and can add contrast, create moods, and symbolize familiar cultural meanings (Johnson-Sheehan, 2012). Americans, for instance, view red, white, and blue as patriotic colors, but Chinese citizens do not (Baker, 2006). Since font and color influence emotions, they can also enhance a document’s memorableness by making information more stimulating (Berger, 2013). The more arousing information is, the more likely it will be encoded into long-term memory.

In Universal principles of design, Lidwell, Holden, and Butler (2010) frequently connect effective design to attention and memory. Most notably, they suggest making information distinctive to encourage “elaborative rehearsal” or “deep processing” (p. 72) and using pictures and text together to facilitate better recall (p. 184). The more distinctive a stimulus, the more people need to process it. The more they process it, the more they encode it into memory. Imagery can add distinctiveness as well as reinforce messages. Similarly, Kostelnick and Roberts (2011) describe how “emphasis strategies” can make information more distinctive and thus “draw the reader’s attention to key elements in a visual field” (p. 175). Through manipulating attention, effective design can help readers encode information into long-term memory.

Audience and memory

The proposed heuristic hinges on understanding an audience’s collective self-schema, or collective memory and identity. As philosopher Charles Scott (1999) explains, “people cannot think similar thoughts without sharing similar cultural, institutional memories” (p. 247). For example, the phrase, “It’s the economy, stupid,” has a clear meaning and reference point for those whose shared cultural memory includes Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign. Seeing the phrase could prompt this group to focus on some core problem or essential information the author wishes to emphasize. But for other readers, the phrase will lack meaning without additional explanation; they will neither recognize the phrase nor think what the author intends for them to think upon reading it. Technical jargon offers countless more examples of shared memory’s importance to communication as well as memorableness.

In one sense, my research situates Kenneth Burke’s theories of identification and consubstantiality in the context of document design (in addition to writing and rhetoric). In A rhetoric of motives, Burke (1969b) explains, “insofar as their interests are joined, A is identified [emphasis in original] with B. . . . In being identified with B, A is ‘substantially one’ with a person other than himself . . . at once a distinct substance [or individual] and consubstantial with another” (pp. 20–21). In his earlier work, A grammar of motives, Burke (1969a) states that a group’s consubstantiality most often comes from a shared cultural or historical background, or what Scott (1999) calls “similar cultural, institutional memories” (p. 247). Burke says the group’s individual members form their identities, or self-schema, in terms of the collective’s commonplaces or discourse community (Porter, 1986). Collective self-schema influence the audience’s judgement of information’s relevance, which in turn influences the effort to remember that information.

Lynda Walsh, Derek Ross, and Kendall Phillips each allude to the potential for engaging an audience’s (self-)schema and influencing its memory. In her survey of STEM topoi, Walsh (2010) writes that topoi link “people, texts, and experiences” (p. 122), and discussion sections in STEM articles relate novel findings to familiar patterns (p. 142). Though she does not explicitly address memory, one can view the linkages of topoi as engaging collective memory and the connecting of novel and familiar knowledge as reshaping readers’ schema. Ross (2013) adds, “commonplaces . . . actuate an audience’s existing understanding of a situation” (p. 91). In other words, commonplaces frame a topic in terms of the audience’s existing schema. As Ross explains, a given commonplace activates “a system of associations … that allows complex concepts to be rapidly processed against previously established knowledge [or schema]” (p. 96). Using the word “proof,” for example, invokes scientific ethos without actually giving scientific facts and figures (p. 96). Lastly, Phillips (2010) argues that enthymemes involve memory since the audience must supply an unstated premise cued by the writer. The author’s cue might fail if the audience does not share the memory of that premise. Taken together, Walsh, Ross, and Phillips show that writers must consider their audience’s collective memories and self-schema when developing content.

Methods

Populations, benefits, and risks

This research was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of Old Dominion University. The subjects, or audience, for this study consisted of ten high school and middle school teachers in the Clearwater School District in Piedmont, Missouri, (eight female, two male) and ten students enrolled in an evening community college course taught in Clearwater High School (five female, five male). These populations were a fairly authentic audience for the hallway’s documents. In educational research, the word authentic generally refers to tasks, simulations, or problem-solving similar to real-life experiences and situations (Nicaise, Gibney, & Crane, 2000; Perkins & Blythe, 1994). Many posters and flyers contained information relevant to the teachers, and the rest were aimed at roughly the same demographic as the college students. The documents were also authentic in terms of my study’s purpose, for they were competing to attract attention. A hallway decorated with posters and flyers can be characterized as an embodiment of Lanham’s attention economy, in which attention is a commodity. While technical communicators work in manifold genres, their work occurs within the attention economy, and thus they can benefit from knowing what qualities make documents both arresting and memorable.

All subjects were selected based solely on their willingness to participate in the study; I did not offer any incentive, and there were no negative consequences for nonparticipation. Both populations were readily accessible and eighteen years or older during the study. Participation may have benefited subjects by increasing their awareness of effective design strategies, but it did not pose any risks. To exercise extra caution, I replaced subjects’ names with alphanumeric codes to preserve their anonymity and minimize any unforeseen risks of their participation.

Procedures

The following procedures could be adapted to various workplace contexts and rhetorical situations. I described the study’s purpose and read the Notification Form to each subject (Appendix A). Next, I asked each subject to walk, individually, down the main hallway of Clearwater High School, and to allow his or her attention to naturally wander. I conducted the study after school hours, and the hallway was empty, silent, and free of distractions. It was already decorated with a variety of bulletin boards, posters, and flyers by the school’s administrators, teachers, and students. Some of these documents, such as anti-drunk driving messages, had been posted for a number of years. Others were posted more recently to advertise a school club or an upcoming event.

Following each subject’s walk, I conducted an oral interview to avoid the mnemonic effects of a written survey. I asked the subjects for some demographic and contextual information as well as their recollections (Appendix B). Collecting this information inserted some time between viewing the hallway’s documents and recalling them, ensuring that I measured long-term memory rather than short-term or working memory. It also enabled potential correlations of subjects’ teaching areas or (intended) majors/minors, grade levels, and attentional contexts with their responses and the documents. I did not ask for more detailed demographics (such as race, sex, or age) because I identified this information while conducting the interviews.

Additionally, I asked the subjects if they recalled seeing any of the hallway’s posters or flyers before participating in the study. Asking subjects about their prior exposure to the documents allowed me to assess the impact of repetition on a poster or flyer’s memorableness. Repetition, of course, is a common and effective encoding strategy, and it is also part of the rhetorical situation for posters and flyers (i.e., they are meant to be seen repeatedly over a given timeframe). Some might view previous or repetitious exposure to the documents as a confounding variable. However, the study’s results indicate that prior or repeated exposure, or lack thereof, did not significantly affect the subjects’ recollections. While repetition cannot be ignored since it is inherent to a poster’s or flyer’s rhetorical situation, repetition is not the decisive characteristic of memorable documents.

One week after each subject’s first interview, I conducted a follow-up interview to test the documents’ impact on memory over time by determining what, if any, information had stuck and why (Appendix C). In a 1991 study, Conway et al. replicated Ebbinghaus’ “forgetting curve” with college psychology students (Wood, Wood, & Boyd, 2008, p. 217), confirming that forgetting occurs in a regular, measurable pattern. For this study’s purposes, the forgetting curve indicated a reasonable time interval at which subjects could be expected to recall some information. At the second interview, my subjects did not view the documents or walk the hallway again. Instead, they recalled information and details to the best of their abilities, and I added these responses to my notes. Finally, I photographed the bulletin boards, posters, and flyers for later analysis.

Data analysis and coding

Like the study’s procedures, the following methods of data analysis could be adapted to various contexts within technical communication. To analyze the interview data, I counted and coded both the information and specific details that the subjects reported. Then I further separated the data based on the subjects’ previous exposure to the documents and demographic information. Lastly, I compared the survey responses to the actual documents, observing connections among the subjects’ perceptions and the documents’ actual designs, content, styles, etc. These methods enabled a more detailed understanding of the interaction(s) among the texts and the subjects’ attention and memories.

Counting the remembered units of information and details required qualitative interpretations. I counted any response that indicated a coherent memory as a single unit of information. For example, the Constitution, Bill of Rights, and Declaration of Independence were three different posters, but I counted them as one “unit” of information since subjects invariably reported them together. Then I distinguished between information and specific details based on scope. If a subject recalled the Constitution, for instance, then I coded that as recalling information. If a subject recalled the font of the Constitution then I coded that as recalling a detail. To most accurately depict the responses, I sometimes double-counted recollections as both information and detail. If subjects remembered “the FBLA poster,” for instance, then they remembered the poster as a unit of information as well as the specific detail of its title or most prominent text (FBLA stands for Future Business Leaders of America).

Coding the subjects’ responses about why they recalled certain information and details also required subjective analysis. My codes for these responses consisted of common design and psychological concepts from Universal principles of design (Lidwell, Holden, & Butler, 2010), Dynamics in document design (Schriver, 1997), Made to stick (Heath & Heath, 2007), Contagious (Berger, 2013), and psychological research on memory and attention (Appendix D). The subjects’ responses did not always neatly fit under a particular design or psychological concept. I found it necessary to use multiple codes for some reported reasons for recalling information; for example, “schema” and “relevance” were often intertwined. Since certain responses could not be described in exclusive terms, I believed that using multiple codes was more accurate and appropriate.

Additionally, I coded the types of specific details the subjects recalled. These details were always either an image or some text. I used the following subcategories to code the types of images recalled: archetype, iconic representation, person, scene, object, and aesthetic. “Archetype” refers to images invoking a concept, and “iconic representations” use images to symbolize something. The other categories are self-explanatory. For text, I used these sub-categories: name, title, date, slogan, and action. The term “title” means the most prominent text on the poster or flyer, whether it is clearly intended to be a title or simply became a title in the subjects’ responses. “Slogan” refers to emphasized statements (“Don’t Drive Drunk”), and “action” refers to promoting a desired action (e.g., paying club dues). “Name” and “date” are self-explanatory. Next, I used Schriver’s five text-image relationships (redundant, supplementary, complementary, juxtapositional, and stage-setting) to describe the subjects’ responses that invoked the relationships between text and imagery. Finally, I also included “color” since this term most accurately described several recollections of specific detail.

Results

The study’s results clearly answer its research questions:

- What design elements cause a reader to attend to information in such a way that he or she will remember that information?

- How do these design elements enhance a document’s memorableness?

Color, contrast, and imagery can attract an audience’s attention and facilitate encoding information and details into long-term memory. Color, contrast, and imagery are naturally attention-catching, especially if used together (e.g., color can create contrast). But these elements do not automatically enhance memorableness. In this study, the most memorable documents appealed to readers’ existing self-schema, or identities, leading them to ascribe relevance or importance to the information that made it worth remembering.

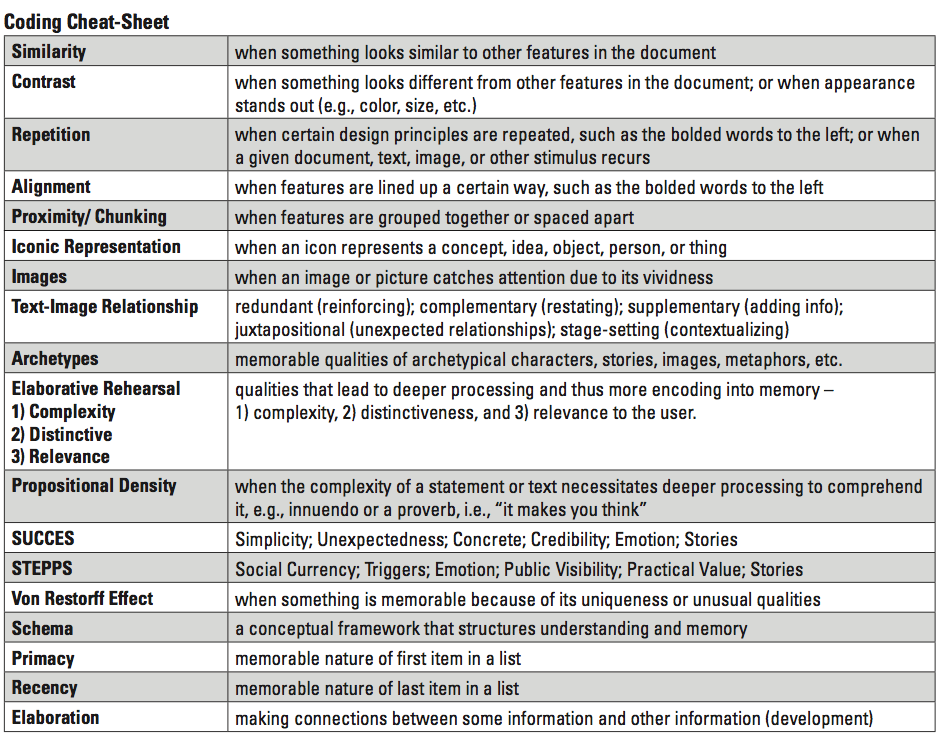

Table 1 displays the amount of information and specific details each subject recalled during each interview as well as whether they reported previously seeing the documents in the CHS hallway. As explained above, I distinguished between “information” and “specific details” based on scope, and sometimes I double-coded a response as both. The subjects’ recollections were very consistent from one interview to the next, indicating that documents can—and do—influence long-term memory.

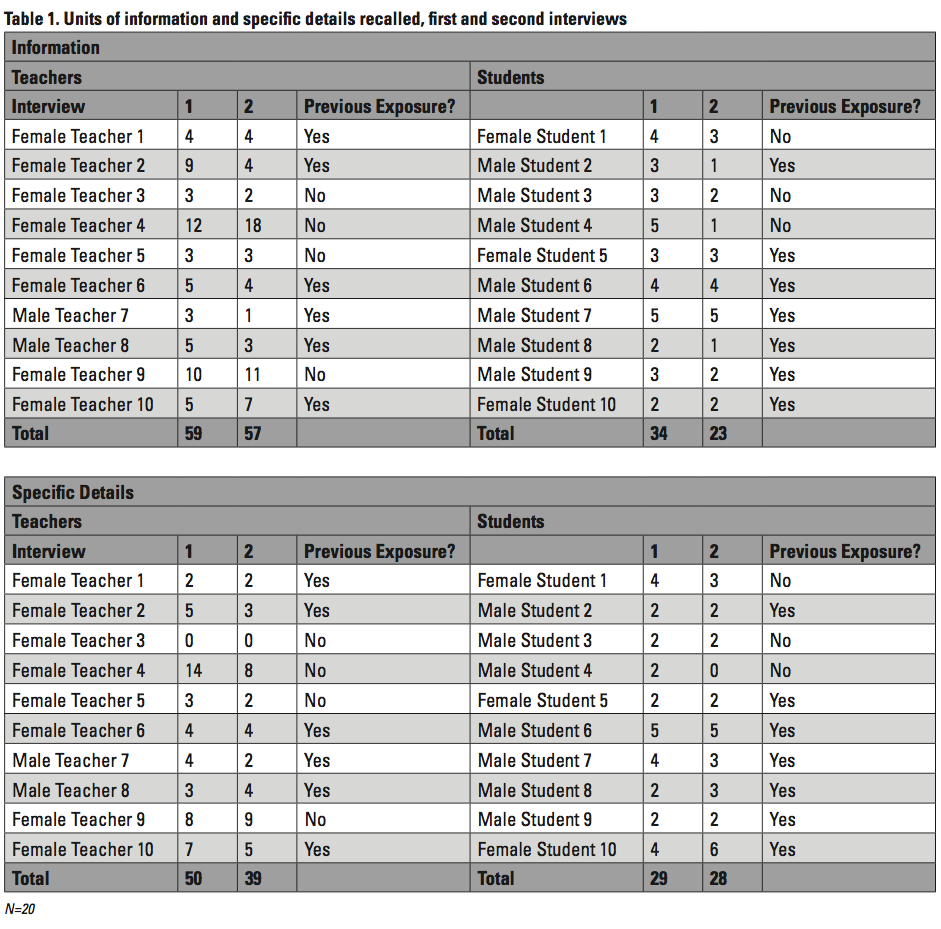

Table 2 displays the number of each type of specific detail recalled by the subjects in both interviews. As explained earlier, I coded the remembered details as subcategories of imagery, text, or the relationship between imagery and text. The table shows that text-title, text-slogan, text-action, and image-archetype were by far the most common codes, suggesting that easily encoded details may be more memorable.

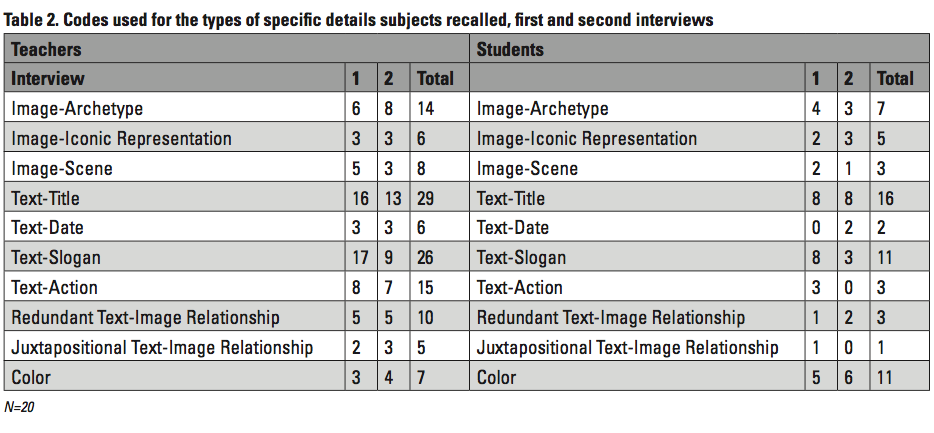

Table 3 lists the reasons subjects gave for recalling information and specific details. (Some of the codes in Appendix D are not listed since they did not describe or apply to any of the subjects’ responses.) Contrast-color, relevance, and schema were the most-used codes for the subjects’ responses when asked why they recalled information. Relevance and schema were the most common codes for subjects’ reasons for recalling specific details. It appears that relevance, memory, and schema are intertwined. That is, schema seem to influence judgments of relevance, which in turn influence attention and encoding.

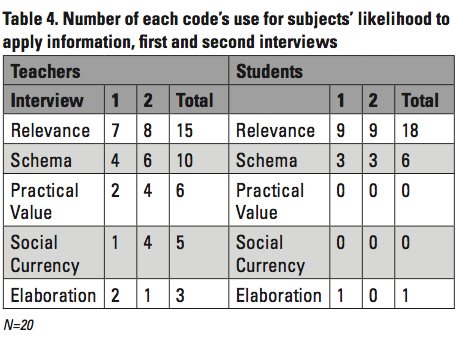

At the end of each interview, I asked subjects how likely they would be to apply any of the information or details they recalled. Table 4 shows that relevance and schema were the most-frequent codes. Typically, relevance refers to responses dismissing the documents’ possible relevance. Most of the teachers indicated that the information was not relevant; some said it was relevant because they were either teachers or parents of the children to whom the information was directed. Similarly, most of the students viewed the information and details as irrelevant; they were in college and the documents were directed at high school students. The subjects’ self-schema, or identities, as teachers and college students influenced them to perceive the documents as irrelevant. This judgment occurred even for the alcohol and drug abuse posters, whose messages, arguably, should have nearly universal relevance.

Qualitative examples and analysis

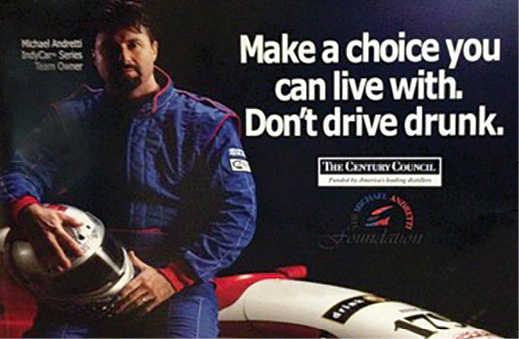

Thanks to their clever use of color, contrast, and familiarity, the most-remembered documents were the Future Business Leaders of America (FBLA) poster (Figure 1) and the racing-themed drunk driving poster (Figure 2). The FBLA poster’s high-contrast design captured attention, and the information being delivered was familiar to the subjects; the subjects already possessed a schemata, or conceptual framework, for the FBLA club. The drunk driving poster used contrast through the colors of the racecar, racing suit, text, and background. The text “Don’t drive drunk” taps into the widely shared schema of anti-drunk driving messages. The text/slogan is supported by the redundant, reinforcing racing imagery, which invokes a familiar archetype or schemata. Subjects consistently recalled the “racecar driver,” but not Michael Andretti who is shown and named in the poster (see Figure 2). Most likely, the racecar driver schemata already existed for them while schemata for Andretti did not. Both posters were consistently recalled among the subjects, showing that certain strategies can make documents memorable.

But surprisingly often, documents were either noticed or ignored due to the subjects’ differing self-schema. Only a few parents whose children were planning to take the ACT noticed a flyer about an upcoming ACT test enough to encode and recall it. A paper cross was hanging from one teacher’s door for all to see, but only a religious studies student noticed it. Only one subject noticed a flyer for a gun raffle, and she described herself as a hunter. These are only a few notable examples of how one’s existing identity, or self-schema, seems to determine what one notices, encodes, and remembers. Logically, the audience’s demographics should exert some influence on its self-schema, although my small sample size did not yield consistent trends based on specific demographic factors.

Limitations

Some subjects reported seeing the posters and flyers in the hallway prior to participating in the study. One might view previous or repetitious exposure to the documents as confusing whether the subjects recalled documents due to their memorable characteristics or due to repeatedly seeing and encoding them. Moreover, the subjects’ performance in the follow-up interviews may have been improved thanks to seeing the documents between interviews, this time with greater cognizance. But as Table 1 shows, repetition did not give any subjects an advantage, and in fact, some subjects without any previous exposure to the documents performed better than subjects with it. It is also possible that repetition actually inhibited some subjects’ recall, since repeatedly seeing a stimulus can inoculate one to its presence. But given the similar number and type of memories among all subjects, I believe repetition was an insignificant limitation on subjects’ performance whether it may have benefited or inoculated them.

Reporting memories may have helped further encode them into the subjects’ long-term memories, an unavoidable limitation in all but the most tightly controlled research designs. I avoided such designs due to my fear of creating an inauthentic context, circumscribing the study’s scope, and preventing the subjects from contributing any surprising or unexpected responses. Also unavoidable in this design, the subjects may have made a special effort to encode the posters and flyers they reported during the first interview so that they could “pass the test” of the second interview by recalling the same documents. This tendency could be especially true of the students, who must often prove their knowledge. Yet even a more tightly controlled, inauthentic study would likely suffer from the possibility of subjects striving to perform well.

Other possible limitations include the distance between the subjects and the intended audience of the documents as well as the possibility of personal interest in certain documents. The subjects may not have remembered information and details as well as they could have because of difficulty relating to documents intended for a younger audience with different concerns. Conversely, some subjects may have remembered certain documents due to a personal interest in their content. In either case, the study’s purpose was to determine what qualities make documents memorable, not to evaluate the subjects’ recall. Perhaps the subjects’ recall suffered due to the study’s design, but the study still yields insight into memorableness. While possibly confounding the study’s raw data, the effect of personal interest also supports the argument that collective self-schema affect readers’ recall.

Suggestions for future research

Future researchers could repeat this study and correct for its limitations. A researcher might use different documents that more closely fit the subjects or different subjects that more closely fit the documents. Different genres, such as essays or reports, could be used instead of flyers and posters. Various audiences could replace teachers and students. Researchers could also design a more tightly controlled experiment that avoided overtly asking the subjects for their recollections, minimizing the mnemonic effects of reporting their memories and/or preparing for a follow-up interview. Additionally, material space and context could be foregrounded in future research. Different spaces position us to do or not do certain things (e.g., a hallway vs. a waiting room), which may affect our formation of memories.

Discussion

This study complicates existing perspectives on document design and suggests alternative practices for technical communicators. Current design practices focus on arranging information in clear, easy-to-follow layouts with aesthetic appeal and directing the audience’s attention through said layouts. In this study, however, contrast, color, and redundant text-image relationships exerted the strongest influence on the subjects’ attention and memories, whereas other design principles and visual rhetoric had little to no impact. The results emphasize the importance of these elements’ use and also suggest the benefits of reframing other design principles as ways to achieve them. For instance, principles like alignment and proximity can be used to add contrast to titles, headings, or other information. At minimum, technical communicators would be well-advised to focus more on using contrast, color, and imagery, especially when conveying essential information that ought to be indelible. Effort at efficiency, aesthetics, and other design principles has its own value and reward, but strong contrast can have a much more memorable impact.

More importantly, this study suggests that design attracts attention but does not necessarily improve memorableness. Both practitioners and textbooks expend tremendous energy on document design, yet design by itself does not guarantee effectiveness in communicating, much less impacting readers’ long-term memories, beliefs, and attitudes. To communicate memorably to a given audience, a writer or designer must tap into that audience’s existing collective self-schema so the readers will ascribe relevance to the document and its information, which in turn will motivate their encoding of that information into long-term memory. A person’s self-schema shapes the perspective by which he or she processes information, filters the relevant and the irrelevant, and focuses and allocates attention (Markus, 1977). By filtering information, self-schema determine what can be encoded and recalled. The more a document engages self-schema, the more memorable, impactful, and effective it will be.

Whenever the audience is larger than one person, we must think about the audience’s self-schema as a collective. Kenneth Burke explains that individuals form and define their identities in terms of the collective, making themselves simultaneously one and not one with it. This process of identification establishes a common interest among otherwise divided people, leading to a feeling of unity or oneness that Burke calls consubstantiality. Consubstantiality most often derives from a shared cultural or historical background (Burke, 1969a, 1969b). This shared knowledge-base—or public memory or collective schema—enables distinct individuals to think similar thoughts (Scott, 1999; Phillips, 2004; Walsh, 2010; Ross, 2013).

Technical communicators may identify an audience’s collective self-schema any number of ways, augmenting their usual audience analysis practices. Members of a given organization usually learn about its history, values, structure, purpose, policies, procedures, and so forth in some kind of orientation and then continue learning about the organization while working for it. Thus, technical communicators can safely assume the presence of schema for the organization’s history, values, etc., in an organizational audience’s collective memory. While not influential in this study, demographics may also provide key clues to an audience’s collective memory and schema. Certain age groups, races, or ethnicities may include certain events or narratives in their collective memory that others do not. This collective memory contributes to a shared identity, or a collective self-schema, which then filters information.

Of course, certain departments within the same organization as well as certain groups within the same citizenry might have very distinct experiences and perceptions. If possible, then, one should narrow the intended audience and focus the analysis as much as possible. This may be difficult or impossible, however, when technical communicators have multiple audiences with different expectations and agendas for the same document (Reiff, 1996). However, any given audience belongs to a common discourse community whether it is as general as “America” or as specific as “corporate tax attorneys” (Porter, 1986). Obviously, more general discourse communities like America or Boeing will encompass multiple audiences. In any case, a given discourse community’s common paradigm, concepts, and language can be viewed as a collective memory or schema.

Whether focusing on common experience, demographic, or discourse, it is clear that communication depends on shared knowledge and schema and that memorableness relies on engaging the attentional filter of self-schema. A document’s color, contrast, and imagery draws our attention, and then we process its information through our self-schema, determine its relevance, and either encode or forget it. If technical communicators focus too much on design, even contrast and imagery, they may fail to push information through readers’ filtering self-schema and thus fail to communicate. Conversely, engaging self-schema can be a powerful rhetorical strategy. Readers may be aware that their assessment of relevance involves their identities as teachers, students, parents, etc., but they do not consciously recognize their self-schema’s influence. Being unconscious, the influence can be potent.

Heuristic for engaging collective schema

Once an audience’s collective self-schema has been identified, analyzed, and understood, several strategies can engage the self-schema so that the audience ascribes relevance to information and thus endeavors to encode the information into long-term memory:

- Convey practical value.

- Use contrast, color, and imagery.

- Tap the familiar.

- Use unexpected elements.

- Build social currency.

- Arouse emotion.

This is likely only a partial list of strategies; future research may reveal many more, but these strategies seem promising based on my secondary research and my study’s results.

If information has practical value, people will strive to remember it for later use (Berger, 2013). Memorable communication, therefore, should convey information’s practical value for the audience. In many cases, the value may be obvious to a reader due to his or her context. As one subject said, the date of the upcoming ACT exam was relevant and useful because his daughter wanted to take it. A software programmer will likely see practical value in a technical description of the client’s needs and desires for the program. In other cases, information’s value may need to be conveyed. An end-user might ignore a section of an instruction manual with unclear practical value, but an attention-catching statement of the section’s value and/or necessity could prompt the end-user to read it after all. Of course, information’s value will vary according to the audience’s needs, necessitating understanding one’s audience and its collective self-schema.

Even the most practical message must receive some attention before it can be perceived and encoded. Contrast and color create a natural distinctiveness, especially if used together, that arrests attention, indicates importance, and prompts encoding. Imagery engages interest and attention, symbolizes the text’s message, builds repetition into the document, and provides another method for tapping into the audience’s collective self-schema. The racecar driver was not needed for the message, “Make a choice you can live with. Don’t drive drunk” to make sense. But that image added visual interest, engaged attention, subtly reinforced the theme and content, and, most importantly, tapped into a collective schema for racecar drivers. The image helped make this poster one of the most memorable documents in the study. Technical communicators can similarly use contrast, color, and imagery to both direct attention and tap into readers’ schema; the right color and image, for example, could symbolize the textual message, such as when one uses bright red font and a hazard symbol to reinforce a warning.

Familiarity influenced my subjects’ recollections because the information was already present in their schema and thus easier to re-encode and/or retrieve. Many things may be familiar to a given audience based on its socio-cultural and institutional memory, but well-known titles, slogans, and archetypes stand out in this study. Teachers and students alike included the familiar title “FBLA” in their self-schema, which facilitated their encoding of the poster even though most did not find its information personally relevant. In some cases, my subjects even transformed less-familiar information, illustrating familiarity’s mnemonic power. The decades-old slogan “Don’t drink and drive” was already present in their schema and was thus more-often reported (i.e., more memorable) than the more concise phrase they actually saw and read, “Don’t drive drunk.” Similarly, the archetype of a “racecar driver” was more familiar to the subjects than Michael Andretti, so they encoded his image as this generic archetype and ignored his name on the poster. Therefore, technical communicators should identify the titles, slogans, and archetypes already present in the audience’s collective schema, and then they should use this collective familiar to make their documents easier to encode and recall. A company’s marketing slogan, mission statement, or logo might seem extraneous to internal audiences, but such additions could facilitate encoding of the document and its information.

Of course, writers must sometimes convey the unfamiliar. If familiarity influences memory so strongly, then it may be disproportionately difficult to make the unfamiliar memorable. One strategy might be to identify some subtle or hidden familiarity, such as an applicable image or saying that one would not normally associate with the unfamiliar information. Juxtaposing the familiar and unfamiliar could not only attract attention through surprise but also help alter an existing schema or create a new one. Another option could be parodying something familiar, creating new entries within existing schemata. Changing a well-known catchphrase to include an unfamiliar term or detail, for instance, creates a bridge between the familiar and unfamiliar. But it could also be possible to embrace the unfamiliar. According to Heath and Heath (2007), unexpected elements can break schema by alerting people to errors or inconsistencies. People form schema because they facilitate cognition and memory. If they are incorrect, people want to correct them. Unexpected elements arouse curiosity and prompt the revision of schema. The unfamiliar, therefore, can be a mnemonic aid if presented as a knowledge gap that needs to be filled or corrected. To accomplish this, technical communicators can inform readers what they do not know and why they need to know it before launching into the information itself. Although some concision or efficiency may be lost, the information will become more memorable and impactful.

By nature, people try harder to encode ideas or experiences that they wish to share later, and Berger (2013) explains that both social currency and arousing emotions tend to motivate sharing. An idea has social currency if it garners a person social approval by making him or her seem remarkable in some way. Gaining social approval is a fundamental human motivation, making information with social currency worth remembering. Technical communicators, then, can emphasize the practical, helpful, humorous, shocking, or otherwise remarkable nature of the information they present, prompting readers to view their documents as worth remembering and sharing. Berger has also found that people are less likely to share information that causes less-stimulating emotions like contentment or sadness. But arousing emotions like excitement, awe, anxiety, or anger make people want to take action, including sharing whatever produced these stimulating emotions. Thus, even in technical documents, one may try to evoke or create rousing emotional connections to information rather than only emphasizing its importance or practicality.

When used together, these strategies should prompt audiences to view information as relevant and worth-remembering so they will incorporate it into their existing self-schema and/or their schema for the topic at hand. Effective design organizes information and directs readers’ attention, but design alone does not make information impactful or memorable. Contrast, color, and imagery draw attention to the information to be encoded. Then, familiarity can facilitate encoding, unfamiliar knowledge-gaps can arouse curiosity, and both familiar and unfamiliar ideas can be imbued with practical value, social currency, and arousing emotion. Readers are more likely to encode information with these qualities into long-term memory, where that information can have a lasting impact on their knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and actions. Thus, the proposed heuristic can help technical communicators produce more memorable, effective documents.

References

Allen, N. (1996). Ethics and visual rhetoric: Seeing’s not believing anymore. Technical Communication Quarterly, 5(1), 87–105.

Baker, W. H. (2006, December). Visual communication: Integrating visual communication into business communication courses. Business Communication Quarterly, 69(4), 403–407.

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Berger, J. (2013). Contagious: Why things catch on. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Borkin, M., Vo, A., Bylinkii, Z., Isola, P., Sunkavalli, S., Olivia, A., & Pfister, H. (2013). What makes a visualization memorable? IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 19(12), 2306–2315.

Braun-LaTour, K., Braun-LaTour, M., Pickrell, J., & Loftus, E. F. (2004). How and when advertising can influence memory for consumer experience. Journal of Advertising, 33(4), 7–25.

Brumberger, E. (2003a, May). The rhetoric of typography: The awareness and impact of typeface appropriateness. Technical Communication, 50(3), 224–231.

Brumberger, E. (2003b, May). The rhetoric of typography: The persona of typeface and text. Technical Communication, 50(3), 206–223.

Burke, K. (1969a). A grammar of motives. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Burke, K. (1969b). A rhetoric of motives. Berkely, CA: University of California Press.

Carruthers, M. (2008). The book of memory: A study of memory in medieval culture (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge UK.

Dragga, S., & Voss, D. (2001, August). Cruel pies: The inhumanity of technical illustrations. Technical Communication, 48(3), 265–275.

Ehrenberg, A. (2000). How presentation graphs communicate. IEEE International Conference on Information Visualization (pp. 206–212). London: IEEE.

Forehand, M. R., Deshpande, R., & Reed, A. (2002). Identity salience and the influence of differential activation of the social self-schema on advertising response. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(6), 1086–1099.

Francoz, M. J. (1999, September). Habit as memory incarnate. College English, 62(1), 11–29.

Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2007). Made to stick: Why some ideas survive and others die. New York: Random House.

Holst-Larkin, J. (2006). Personality and type (but not a psychological theory!). Business Communication Quarterly, 69(4), 417–421.

Johnson-Sheehan, R. (2012). Technical Communication Today (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Jones, S. L. (1997, June). A guide to using color effectively in business communication. Business Communication Quarterly, 60(2), 76–88.

Kimball, M., & Hawkins, A. (2008). Document design: A guide for technical communicators. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Kostelnick, C. (1996). Supra-textual design: The visual rhetoric of whole documents. Technical Communication Quarterly, 5(1), 9–33.

Kostelnick, C., & Roberts, D. (2011). Designing visual language: Strategies for professional communicators (2nd ed.). Boston: Longman.

Krug, S. (2006). Don’t make me think! A common sense approach to web usability (2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: New Riders Publishing.

Lanham, R. (1993). The electronic word: Democracy, technology, and the arts. Chicago: Univerity of Chicago Press.

Lanham, R. (2007). The economics of attention: Style and substance in the age of information. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lee, J., & Ahn, J.-H. (2012). Attention to banner ads and their effectiveness: An eye-tracking approach. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 17(1), 119–136.

Lidwell, W., Holden, K., & Butler, J. (2010). Universal principles of design: 125 ways to enhance usability, influence perception, increase appeal, make better design decisions, and teach through design. Beverly, MA: Rockport.

Loftus, E. (1997). Creating false memories. Scientific American, 277, 71–75.

Loftus, E. (2005). Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation into the malleability of memory. Learning and Memory, 12, 361–366.

Loftus, E., & Palmer, J. (1974). Reconstruction of autmobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 13, 585–589.

Manning, A., & Amare, N. (2006, May). Visual-rhetoric ethics: Beyond accuracy and injury. Technical Communication, 53(2), 195–208.

Markus, H. (1977). Self-schemata and processing information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(2), 63–78.

McNair, J. (1996). Computer icons and the art of memory. Technical Communication Quarterly, 5(1), 77–86.

Nairne, J. (2011). Psychology (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Nicaise, M., Gibney, T., & Crane, M. (2000). Toward an understanding of authentic learning: Students perceptions of an authentic classroom. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 9(1), 79–94.

Nielson, J. (1999). Designing web usability: The practice of simplicity. Indianapolis, IN: New Riders Publishing.

Perkins, D., & Blythe, T. (1994). Putting understanding up front. Educational Leadership, 51(5), 4–7.

Phillips, K. R. (2004). Framing public memory. (K. R. Phillips, Ed.) Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

Phillips, K. R. (2010, March–April). The failure of memory: Reflections on rhetoric and public discourse. Western Journal of Communication, 74(2), 208–223.

Porter, J. (1986). Intertextuality and the discourse community. Rhetoric Review, 5(1), 34–47.

Regan, B. (1998). Validating a 3D layout for memorable graphs. Australasian Computer Human Interaction Conference. Adelaide, SA: IEEE.

Reiff, M. J. (1996). Rereading ‘invoked’ and ‘addressed’ readers through a social lens: Toward a recognition of multiple audiences. JAC: A Journal of Composition Theory, 16(3), 407–424.

Ross, D. G. (2013). Common topics and commonplaces of environmental rhetoric. Written Communication, 30(1), 91–131.

Schriver, K. (1997). Dynamics in document design: Creating texts for readers. New York: Wiley.

Scott, C. E. (1999). The time of memory. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

van Ittersum, D. (2007). Data palace: Modern memory work in digital environments. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 11(3). Retrieved Aug. 7, 2014, from http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/11.3/binder.html?topoi/prior-et-al/about/abstract_vanittersum.html

van Ittersum, D. (2009). Distributing memory: Rhetorical work in digital environments. Technical Communication Quarterly, 18(3), 259–280.

Vance, V. J. (1996, December). Typography 101. Business Communication Quarterly, 59(4), 132–134.

Walsh, L. (2010). The common topoi of STEM discourse: An apologia and methodological proposal, with pilot survey. Written Communication, 27(1), 120–156.

Whittemore, S. (2008). Metadata and memory: Lessons from the canon of memoria for the design of content management systems. Technical Communication Quarterly, 17(1), 88–109.

Whittemore, S. (2015). Rhetorical memory: A study of technical communication and information management. Chicago: University of Chicago UP.

Williams, R. (2008). The non-designer’s design book (3rd ed.). Berkeley, CA: Peachpit Press.

Wood, S., Wood, E., & Boyd, D. (2008). The world of psychology (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Yates, F. A. (1966). The art of memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

About the Author

Eric Sentell teaches technical communication, composition, and visual rhetoric at Southeast Missouri State University. He holds a Ph.D. in writing, rhetoric, and discourse studies from Old Dominion University and an M.A. in composition and rhetoric from Missouri State University. He has previously published articles in Relevant Rhetoric and the Writing Lab Newsletter. His research interests include memory, design, audience, and visual rhetoric. He is available at jsentell@semo.edu.

Manuscript received 30 September 2015, revised 14 January 2016; accepted 14 February 2016.

APPENDIX A

Notification Form

Title of Project: Creating Memories

Investigator: Author

Department: English

Phone number: xxx-xxx-xxxx

The purpose of this project is to investigate readers’ self-reported reasons for remembering information from a given document.

I understand that, as part of this project, I will view documents and then report what I recall from them and why I recall this particular information. I will provide this information once at the beginning of my participation and again one week later.

I understand that there are no risks associated with this procedure or with my participation in this project.

I understand that my participation is voluntary; I may refuse to participate and/or discontinue my participation at any time without penalty or prejudice. I understand that my participation or lack thereof will in no way affect my standing at Southeast Missouri State University or Clearwater High School.

I understand that all information collected in this project will be held confidential; I understand that my survey responses will be anonymous and no identifying information about my participation or responses will be collected during the study.

I understand that by agreeing to participate in this project and signing this form, I have not waived any of my legal rights.

I understand that any questions or concerns I have will be addressed by the above named investigator. If I have further questions, I may contact the Responsible Project Investigator, Dr. Julia Romberger, or Author at xxx-xxx-xxxx or Author’s University Email.

APPENDIX B

Interview Questions (First Round)

1) Name?

2) Grade/Year (if applicable)?

3) (Intended) Major (if applicable)?

4) (Intended) Minor (if applicable)?

5) In general, describe the typical context in which you notice flyers or posters. Where are you? What are you doing?

6) After walking down the hall just now, which flyers or posters do you remember?

7) Why do you remember these flyers or posters?

8) Do you remember any specific information from the flyers or posters?

9) What, if any, specifics do you remember from the flyers or posters?

10) Why do you remember this information?

11) How likely would you be to use or apply this information in the future, and why?

12) Do you recall previously seeing the flyers?

APPENDIX C

Interview Questions (Second Round)

1) Which flyers or posters from last week do you remember?

2) Why do you remember these flyers or posters?

3) Do you remember any specific information from these flyers or posters?

4) What, if any, specific information do you remember from the flyers or posters?

5) Why do you remember this information?

6) How likely would you be to use or apply this information in the future, and why?

APPENDIX D

Coding Cheat-Sheet