By José Miguel Santos-Espino, María Dolores Afonso-Suárez, Cayetano Guerra-Artal

Abstract

Purpose: This paper offers an account of the current usage of communication styles and features in MOOC instructional videos. The aim of the study is to provide a better understanding of instructional video patterns and typologies and to find associations between video style usage and course attributes such as the MOOC platform and course subjects.

Method: Five global, generalist MOOC platforms were selected for this study, which was conducted in two phases: First, a qualitative survey was made to identify frequently used video styles and build a classification scheme. Second, a sample of 115 courses in the selected MOOC platforms was used to account for video features and style frequencies. Various statistical tests were performed to discover associations between course characteristics and video style usage.

Results: Seven video styles were identified as the most frequent in MOOC courses. They fully describe the video stock of 85% of the sampled courses. A typical course uses two different styles. The study reveals two broad competing approaches to display instructional contents in MOOC videos: speaker-centric (a visible person speaks the contents) and board-centric (a large rectangular surface displays the contents). The actual usage of each approach is significantly related to the course subject area: Arts and humanities courses exhibit a preference for speaker-centric styles, while engineering and hard science courses favor board-centric videos. Social sciences and health courses are more neutral.

Conclusion: Current MOOCs are focused on few representational styles, with speakers and boards as the two main models. The observed usage is consistent with a strong attachment to the lecture as an instructional technique.

Keywords: instructional video, MOOC, audiovisual communication, multimedia learning, instructional design

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Popular MOOCs rely on very few and basic communication techniques for building instructional videos.

- The speaker-centric versus board-centric classification characterizes two prevalent representational approaches in MOOC videos.

- Course subject influences the instructional video representational style.

- Current demographic data on MOOC video usage is provided that may be useful for researchers of multimedia learning and for MOOC course designers.

Introduction

xMOOCs and learning with video

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have arisen in recent years as a new model of large-scale online learning in the context of higher education. At present, there are several MOOC platforms that provide thousands of online courses in a wide range of disciplines (see Karsenti, 2013, for a critical review of the MOOC history and characteristics). As of 2015, the media coverage on MOOCs has cooled down compared to the initial hype in 2012, but that does not mean there has been a business decline: The MOOC market keeps growing at a fast pace in course offerings, enrollment, and revenues (Shah, 2015).

MOOCs raised early attention in the scientific community (Liyanagunawardena, Adams, & Williams, 2013), including the research in video-based learning (Giannakos, Jaccheri, & Krogstie, 2014). MOOC providers, teachers, and scholars have a growing interest in the research of instructional video production techniques and how they relate to factors such as production cost, learning efficiency, and student engagement.

It is important to point out that there are two pedagogical models of MOOCs: the cooperative cMOOCs and the more conventional xMOOCs (Rodriguez, 2012). A cMOOC emphasizes collaboration between learners and is a platform that facilitates knowledge sharing and construction, whereas a xMOOC relies on a more traditional pedagogy, based on the delivery of learning content from instructors to learners. xMOOCs have an instructional design heavily based on audiovisuals, most of them short video units provided by the course instructors. Many xMOOC videos have the format of recorded lectures or talks, or screencasts or Powerpoint-like slideshows, all of them presenting descriptive content about the course topic (Karsenti, 2013). cMOOCs follow a connectivist pedagogy, while xMOOCs adhere to a cognitive-behaviorist model (Anderson & Dron, 2011).

xMOOC platforms appeared later than cMOOCs and were usually associated with commercial ventures. Most large and well-known MOOC platforms, like Coursera, edX, Khan Academy, and Udacity are all xMOOCs. This study will focus exclusively on this dominant xMOOC course model and how videos are used to provide learning content. In this article, we will use the term MOOC as a synonym of xMOOC, a common custom in press and research works.

Objectives of this research

In this study, we want to explore the usage of instructional videos in current xMOOC platforms. Our purpose is to obtain a reliable account of the actual usage of communication styles in MOOC videos and how these styles are associated with MOOC characteristics, such as the platform, language, and subject.

The study also proposes a categorization of MOOC video styles, based on their relative frequency and communicative approach. In addition, this article includes a final discussion on the possible causes of the observed usage of video styles.

We believe that this work will contribute to a better understanding of instructional videos in MOOCs and will help researchers in the characterization of video features, production techniques, and communication patterns.

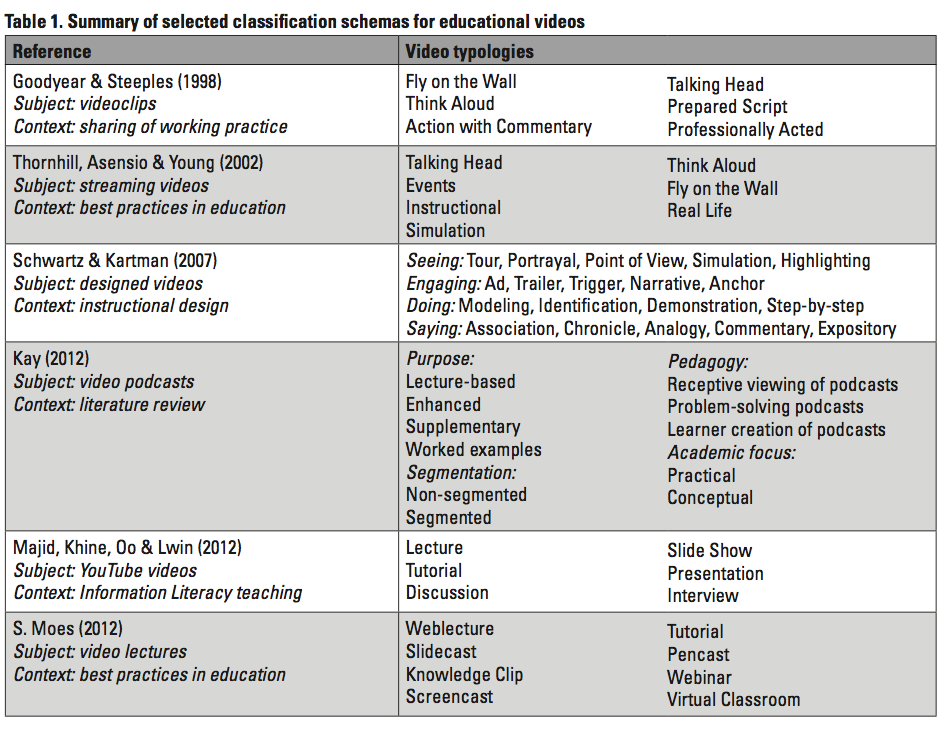

Typologies of online educational videos

To accomplish the aforementioned objectives, it is necessary to define a conceptual framework for categorizing MOOC videos. Extensive research effort has been taken to build general classifications of online educational videos, resulting in several proposals. Table 1 shows a summary of some selected classification schemas, described below.

An early work by Goodyear & Steeples (1998) identified six main communication styles used in video clips shared within communities of practice. The JISC organization (Thornhill, Asensio, & Young, 2002) adapted the Goodyear & Steeples’ classification to the then-emerging field of streaming video in education, suggesting seven frequent usage patterns: talking head, events, instructional, simulation, think aloud, fly on the wall, and real life.

Schwartz and Hartman (2007) developed a conceptual model that classifies educational video around four classes of learner outcomes: seeing, engaging, doing and saying. For each outcome, the authors established four or five video genres, as shown in Table 1.

Kay’s (2012) literature review of research on video podcasts includes a classification that uses four dimensions: purpose, segmentation, pedagogy, and academic focus. Among the video types, Kay identifies lecture-based, enhanced (slides with added voiceover), supplementary (administrative support, real-world demonstrations, summaries), and worked examples video podcasts.

Majid, Khine, Oo, & Lwin (2012) analyzed several features of YouTube educational videos in the field of information literacy. They used six communication styles for categorizing videos: lecture, tutorial, discussion, slide show, presentation, and interview. The EU-funded REC:all project defined a model for lecture capture technologies (Moes, 2012), framed in Bloom’s Taxonomy. Their model involves six types of lectures, such as the knowledge clip, a genre that REC:all project investigated in depth.

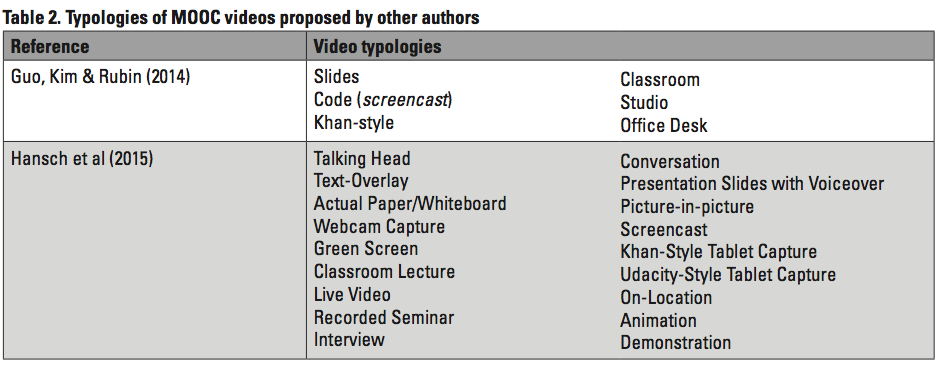

Classifying MOOC video styles

Researchers have tried to characterize and classify the video styles that are prominent in MOOCs. There are two recent works that provide remarkable results on the classification of MOOC videos. In the first study, Hansch et al. (2015) assessed current MOOCs and identified a set of 18 video style typologies (see Table 2) based on their qualitative reviews and interviews with MOOC designers and instructors.

Second, the study by Guo, Kim, and Rubin (2014) measured the influence of video production style over student engagement in MOOCs. The authors labeled videos using six production styles: slides, code (screencast), Khan-style, classroom, studio and, office desk. The study was limited to a small set of courses of scientific and technology disciplines in the edX platform.

Discussion of classification schemas

At present, there is no standardized taxonomy of educational video styles. In addition, the terminology is still maturing as new video techniques emerge and neologisms are coined. We have noticed that older classifications tend to be organized around features, such as teaching purposes or communication patterns, while newer classifications tend to be more aware of genres, a trend that is revealed by the increasing appearance of terms such as screencast, webinar, and the like.

The two MOOC classification schemas share a concern of researchers on the video setting or background, which drives the building of the typologies. Half of the Guo, Kim, and Rubin’s categories are actually scenario settings (classroom, studio, office desk).

Related work

Several systematic characterizations have been devised to classify other video features. Koumi (2006) distilled decades of expertise in The Open University into a multifactorial framework that describes video qualities such as affordances, functions, and usage patterns with a practitioner’s focus. Ploetzner and Lowe (2012) built a characterization of expository animations based on a systematic literature search and analysis. Santos Espino et al. (2013) outlined a multi-layered taxonomy model to classify online instructional video features.

Yousef, Chatti, Schroeder, and Wosnitza (2014) used structured questionnaires to assess teacher and learner preferences on various MOOC course aspects, including video content, user interface, and video layout, but little emphasis was made on video styles. Features that were assessed included the use of slides and teacher image, text size, and text location.

Finally, YouTube is a platform where researchers have made several quantitative studies on instructional video styles and features. Swarts (2012) explored how-to tutorial videos in YouTube to discover links between narrative patterns and popularity. More recently, ten Hove & van der Meij (2015) conducted a survey of a class of instructional videos in YouTube and found significant associations between certain production features and video popularity.

Study Design

Research questions

This research will classify videos according to their communication style: how the instructional contents are expressed in the video by arranging visual items and sounds in space and time. It is important to remark that communication style deals with the representational features of videos and not with the video production technique. Therefore, we will categorize the product outcome, not the way it has been produced.

With this definition given, this study has two main research questions to investigate:

- What are the communication styles and features used in instructional videos in current MOOCs?

- Are there significant differences between MOOC platforms or course subjects, regarding the usage of representational styles in their instructional videos?

Method overview

Five MOOC platforms were chosen for this study: Coursera and edX from the United States, FutureLearn from the UK, MiriadaX from Spain, and FUN from France. These all are generalist MOOCs serving worldwide communities: a global audience for Coursera and edX, English-speaking people for FutureLearn, Spain and Latin America for MiriadaX, and the Francophone community for FUN. We chose not to study popular MOOC sites like Khan Academy and Udacity because they cover very narrow fields of knowledge, like mathematics or computer programming.

The study was developed in two stages. In the first phase, a qualitative survey was made to investigate what types of video communication styles are most frequently used in the selected MOOC platforms. This study resulted in the identification of seven video styles and the emergence of a broad categorization of board-centric and speaker-centric styles, as we will discuss below. The second phase consisted of a quantitative survey of video style usage in a sample of 116 MOOCs. With these data, a statistical analysis (descriptive and inferential) was made to answer the research questions and to extract more general conclusions.

Method for phase 1

The main goal of the first stage was to set up a useful classification schema for the video communication styles. A small sample of courses from the evaluated MOOC platforms was examined by the authors and was contrasted with preceding classification proposals in order to build a taxonomy of styles whose elements should exhibit a good balance of these criteria: (a) meaningful for non-scholars, (b) non-ambiguous, and (c) non-overlapping.

Method for phase 2

Sampling period All the selected platforms offer courses in time windows, so the course population varies over time. In order to reduce sampling biases related to season, five sampling periods were defined in a time window covering the first semester of 2015: February 11–14, March 24–31, April 20–May 11, May 20–June 8, June 18–July 8.

Course selection For FUN, FutureLearn, and MiriadaX platforms, we enrolled in all the courses that were available in each sampling window. Coursera and edX have a large amount of available courses (more than 300 courses during the sampling window), so we enrolled in a subset of courses, following the same sequence shown by the platform’s course search page. Some courses had not published the full course material when the sample was made; those courses having available less than one third of the full syllabus were discarded from the sample.

Video selection For each course, we examined the full stock of instructional videos they contain. Some courses included links to external videos as part of reference material; this kind of video was not considered for the study. Other videos that have been discarded are course presentation videos, welcomes, promotional clips, and descriptions on how to use the course material. Finally, we have not considered recorded hangouts and other additional videos that sometimes can be found in course discussion forums.

Video styles and features For each course, a number of data was collected: subject area (see below), video styles used and other video features, freehand writing or marking, background (plain, office, outdoors), in-video quizzes, use of cartoons, and use of actors instead of instructors. The video styles were coded using the definitions set in Phase 1 by a team of three evaluators. Each course was evaluated independently by two persons. When a discrepancy in the coding occurred, the evaluator pair had to reach consensus on a unanimous decision. Some videos are composed of segments that may use different styles; if this was the case, all styles were accounted for. If a video could not be clearly assigned to any of the seven styles, the evaluator would assign it to the “others” category as well as write an explanation.

Subject areas Every course was assigned to one of these seven subject areas: arts and humanities, business and management, social sciences, natural sciences and mathematics, health and medicine, engineering and computing, and everyday life. This last category has been conceived to assign non-academic, practical courses about common life matters such as training for finding a job.

Phase 1: Identifying Video Styles in MOOCs

Among all the reviewed classification schemas, we have considered the catalog by Hansch et al. (2015) as a good starting point. However, we consider that this typology intermingles different dimensions in a single list, making it unnecessarily long and concealing the existence of some category groupings. For example, the “Talking Head,” “Webcam Capture,” and “Green Screen” types share much more in common than they do with other types; in fact, these three only differ in the scene setting or background. That led us to simplify Hansch et al.’s scheme as well as add the “Documentary” style that we observed in a significant amount of Phase 1 sample courses. We decided to suppress the “Animation” and “Demonstration” types because of the lack of relative frequency in the courses we previewed.

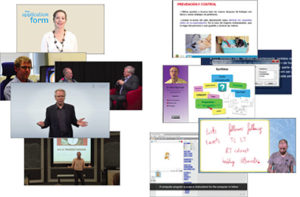

The resulting seven styles are named “Talking Head,” “Live Lecture,” “Interview,” “Slides,” “Screencast,” “Virtual Whiteboard,” and “Documentary.” Some of these terms have well established meanings while others need a precise definition for the context of this research, which we will provide below. Sometimes a MOOC video uses a combination of these basic styles, but usually a single style is the dominant one.

Table 3 sketches the mapping between our seven styles and the list by Hansch et al. (2015). It can be seen that our taxonomy works roughly as a grouping of Hansch et al.’s typologies in higher-level classes.

Style definitions

This section contains definitions for the seven main video styles as they will be considered along this paper. Figure 1 shows screenshots of all these styles. We made an effort to construct definitions that ease the following phase of style coding in the course sample, therefore avoiding ambiguity.

Talking head It is a video podcast whose most frequent shot is a talking human speaker who covers a large frame area (+30%) and is not surrounded by slides or other text-rich elements. The speaker addresses the audience: she or he looks at the camera most of the time in a pretended eye-to-eye contact (the learner is treated as second person). Sometimes overprint text is shown to enforce key ideas of the narration or the scene switches to show another kind of material (still images, short video clips, etc.). Those insertions represent a relatively small amount of video time.

Live lecture It is the live recording of a classroom lecture or conference talk. An in-classroom audience is visible or implied. The learner’s role is third person. The video should show some degree of edition (i.e. switching shots and cameras) but always keeps the overall perception of being recorded in a single take.

Interview One or more persons answer questions about or discuss a topic. An interviewer may or may not be present. There are two main approaches for the interviews: the dialogic (several people are involved in a conversation) and the declarative (each speaker answers a tacit question, but there is no explicit conversation). The key feature that differentiates an “Interview” from a “Talking Head” video is that in the first case, speakers don’t address the audience and don’t show direct eye contact (learner is third person).

Slides In its most basic form, it is an animated sequence of Powerpoint-like slides with a voiceover talk (slideshow or slidecast). Most frequent versions of this style display the speaker as a small “talking head” placed in a marginal area of the frame (most commonly at the right bottom). Sometimes this substyle has been referred to as “picture-in-picture” (Hansch et al., 2015; Kizilcec, Papadopoulos, & Sritanyaratana, 2014), but we prefer to call it a more specific term—“Head and Slides”—to avoid confusion with other picture-in-picture layouts.

Screencast This is the visual recording of a computer session screen output, as defined by Udell (2005). It will usually include a voice narration with a description of the actions being taken.

Virtual whiteboard This style has been popularized by Khan Academy videos. A virtual whiteboard is shown where an instructor draws content (e.g., mathematical formulas, diagrams, or short text). The whiteboard is often blank at the video start. The instructor’s face is usually not displayed, though some variants of this style show human hands and/or a pen doing the drawings.

Documentary This is the standard cinematographic genre whose typical structure consists of a narration and filmed segments of stock material about a topic. The narrator may or may not be displayed; in this latter case, their presence represents a minimal fraction of the video length.

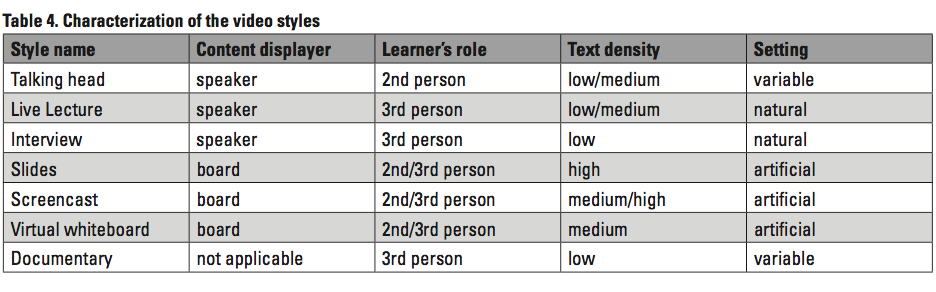

Characterization of styles

Every style can be characterized by a set of features:

The content displayer is the main representational item that provides instructional information within the video frame. All styles but one use a human speaker or a rectangular board for this purpose. We will discuss this in a following section.

The learner’s role is the position of the viewer in the video narrative: second person or third person (O’Donoghue, 2013).

The text density is the average amount of written text that is displayed in the video frame. Some styles use substantially more text than others.

The setting or scenario may be natural (a classroom, an office, etc.) or artificial (chroma display, computer screenshot, etc.).

The characterization for all the styles is shown in Table 4.

Speaker-centric versus Board-centric videos

During our qualitative study, we noticed that most MOOC videos take a single structural item as its main provider of instructional content. Depending on what type of item plays that role, we find two classes of videos: board-centric and speaker-centric.

Board-centric videos use a rectangle-shaped surface (a board) where instructional contents are presented. This board fills a large frame area or the full frame.

Speaker-centric videos use a visible human speaker as the main vehicle to provide content. The speaker is visible most of the time. Sometimes more than one speaker may be present.

Figure 2 shows examples of both style families. Board-centric styles include virtual whiteboard (Khan-style tablet drawings), slides (including Head and Slides), and screencasts. Speaker-centric styles include Talking Head videos, Live Lecture recordings, and Interviews.

Speaker-centric videos tend to provide oral information, while in board-centric videos, the visual information (text or figures) is principal. Visual content items like charts and pictures may be also present in speaker-centric videos, but in that context they often work as a complement to the primary spoken contents. On the other hand, board-centric videos may display a speaker (as a small picture-in-picture or occasional interleaved full shots), but this representation often works as a stylistic complement whose main role is not to provide content by itself but to help in other purposes such as enhancing attention or engagement, as suggested by Kizilcec, Papadopoulos, and Sritanyaratana (2014). Engagement and attraction originated in speaker presence may also be related to the development of an intimate tutorial relationship observed by Adams, Yin, Vargas Madriz, and Mullen (2014) in their exploration of the learning experience of MOOC students.

The board- and speaker-centric divide has links with video production techniques. Board-centric videos tend to be rooted on screen capturing procedures, while typical speaker-centric videos are based on real-life video recordings.

Finally, we have to note that this classification works actually as a spectrum. One can find “pure” board-centric styles, such as a screencast or a slideshow, and “pure” speaker-centric videos like an unedited lecture capture; in the middle, there are styles with a combination of degrees of board and speaker centricity. This occurs with the Head and Slides substyle, which is still board-centric but shows some degree of speaker presence.

Phase 2: Quantitative Survey

Course demographics

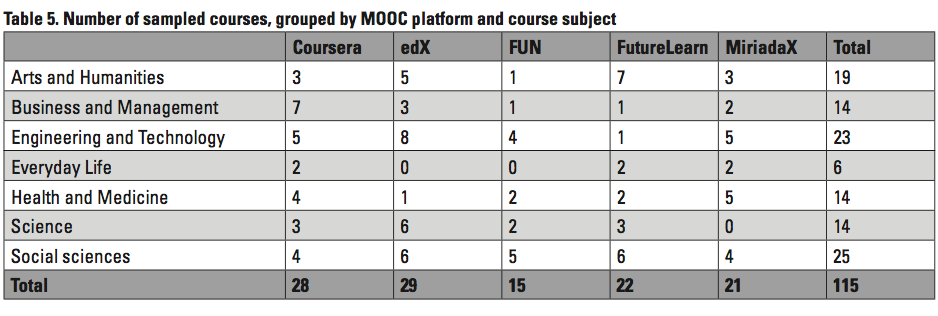

A total of 116 courses were evaluated. One of them didn’t use videos at all, thus it was removed from the study, leaving a total of 115 courses. Table 5 shows the distribution of courses by MOOC platform and course subject area.

Surveyed courses were made by 84 institutions from 15 countries worldwide: the United States (44 courses), Spain (20), the United Kingdom (19), France (15), Latin America (7), Eastern Asia (4), Australia (3), and other European countries (3).

English is by large the most used language (74 courses), followed by Spanish (25), French (15), and Portuguese (1). All courses made in French language were provided by FUN, while Spanish-speaking courses came from MiriadaX (20), Coursera (4), and edX (1). The course in Portuguese was hosted in MiriadaX.

Video styles

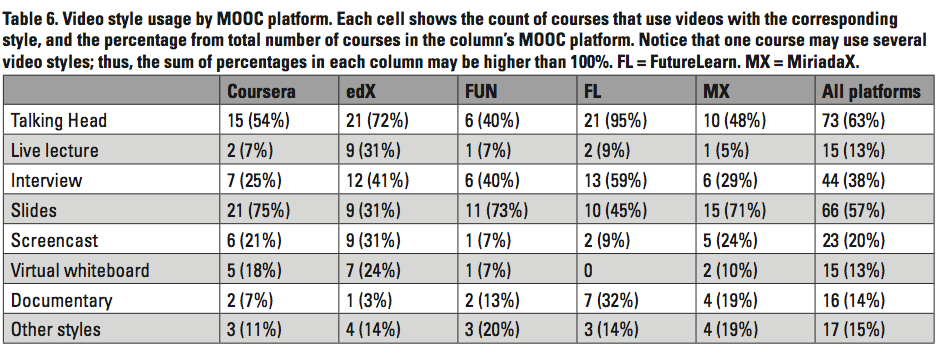

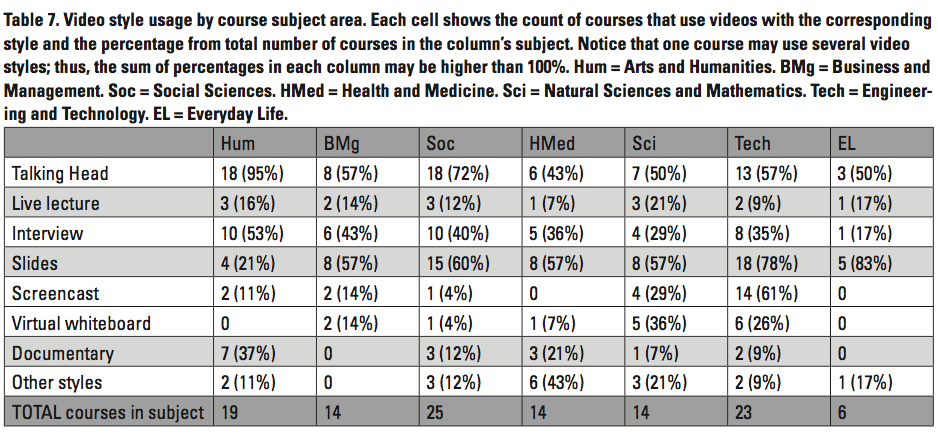

Tables 6 and 7 show the usage of video styles across MOOC platforms and course subjects, respectively. Talking Head and Slides were the most used styles in general, but there were some differences across platforms: Slides was the most used style in Coursera and MiriadaX while Talking Head was the most frequent in edX and FutureLearn.

Slides

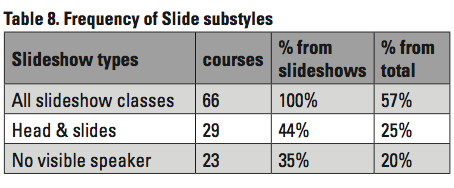

Slide-based videos were the second most frequent style, nearly tied with the Talking Head style. There were several variants of the slideshow whose usage is shown in Table 8. The most frequent format was the Head & Slides, found in 44% of courses with slide-based videos (25% of all courses). It is remarkable that 23 courses (20% of total) used slideshows with no visible speaker.

Freehand writing and marking

Only nine courses contain videos that can be considered pure Virtual Whiteboard (Khan style or similar). This scarcity contrasts with the high reputation that this style holds. We have also accounted for the use of handwriting in any form: occasional writing, marking text areas on screen, etc. A total of 30 courses (26%) exhibit some form of handwriting in their videos. This feature happens mostly over slides (13 courses) and during screencasts (8 courses).

Background and setting

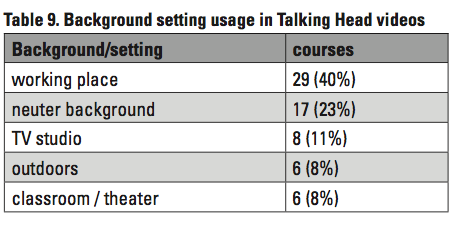

Guo, Kim, and Rubin (2014) speculate about the influence of the background and setting where the speaker is placed. They suggest using natural and simple settings such as an office. This hypothesis applies mostly to our Talking Head style, since the other ones are bound to a natural or artificial setting. We have explored the kind of background that is used in the Talking Head videos. Rows in Table 9 show how many courses use Talking Head videos with a given scenario: a working place or office. a neutral background (i.e. chroma), a TV studio, outdoors, a classroom, a conference room, or a theater.

Other features

Other minor features were also annotated:

- 12 courses made use of actors instead of instructors, mostly in documentary fragments, demonstrations and storytelling.

- 8 courses made use of cartoons and animated movies.

- 4 videos made explicit use of humor to communicate ideas.

- 8 courses used in-video quizzes, 7 of them in Coursera and the other one in edX.

- 4 courses made use of voiceless videos: 3 in MiriadaX and 1 in FutureLearn.

Statistical Analysis

Style diversity

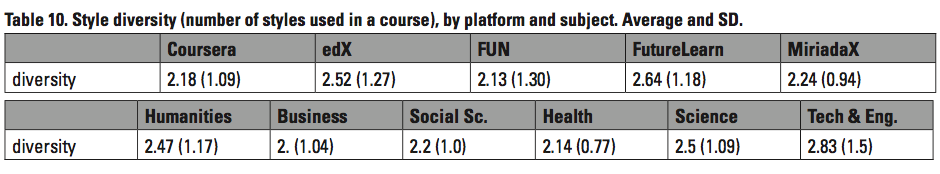

A typical course uses two different video styles (mean=2.36, SD=1.16, mode=2). Individual diversity measures for each platform and course subject are shown in Table 10. FutureLearn and edX hosted slightly more diversity than the other platforms. On the side of subjects, we found a group of lower diversity areas (business & management, social science, and health) and one with higher diversity (arts & humanities, science and technology).

Sixty-three courses (55%) can be entirely described with just three styles: Slides, Talking Head, and Interview. Only 17 courses (15%) used videos that cannot be labeled with the seven styles identified in this study. These additional styles included roleplays, storytelling, cartoons, how-tos, and others. These data reveal a low diversity of styles in MOOC courses.

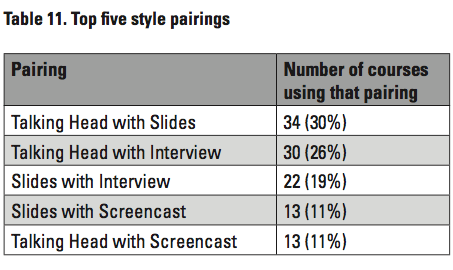

Style co-occurrence

Given that a typical course uses two video styles, we analyzed the co-occurrences of styles within a single course. The most common style pairings are listed in Table 11.

The most frequent pairing (Talking Head with Slides) had a lower frequency than was expected if styles were chosen at random. To obtain deeper conclusions, we performed chi-square tests of independence for all the 21 style pairings (N=115 for all tests). A statistically significant relation (p<0.05) was found in five pairs. For those cases, the Yules’ Q statistic has been calculated to state the sign of the association (positive or negative).

These are the three positive associations:

- Virtual Whiteboard with Screencast (p=0.04, Q=+0.53)

- Virtual Whiteboard with Lecture (p=0.01, Q=+0.64)

- Interview with Documentary (p=0.03, Q=+0.53)

And these are the two negative associations:

- Slides with Lecture (p=0.01, Q=-0.63)

- Slides with Talking Head (p=0.003, Q=-0.54)

Furthermore, we have performed a similar test for independence for Slides against all other styles and against the speaker-centric family as a whole. The results are: (a) the usage of slides and all other styles were independent (χ2=0.236, p=0.627), and (b) a significant negative association was found between slides and speaker-centric videos in general (χ2=8.67, p=0.003, Yule’s Q = -0.64).

This set of associations suggests a trend in course design to avoid combinations of slide-based videos with speaker-centric modalities. The data also suggest that when a speaker-centric course needs to benefit from board-centric instructional material, there is a slight preference for Screencast and Virtual Whiteboard video instead of Slides.

Associations between style and course attributes

We performed chi-squared tests of independence to find statistically significant relations between the style usage in courses and other variables: platform, language and style. An alpha level of 0.05 has been used for all tests. A Fisher’s Exact Test was made when data were not adequate for chi-squared tests. When considering subjects, we have excluded “Everyday Life” courses, since this subject category involves only 6 courses.

Given those considerations, the only significant relation found was between style usage and MOOC platform: χ2(24, N=115) = 43.41, p<0.01.

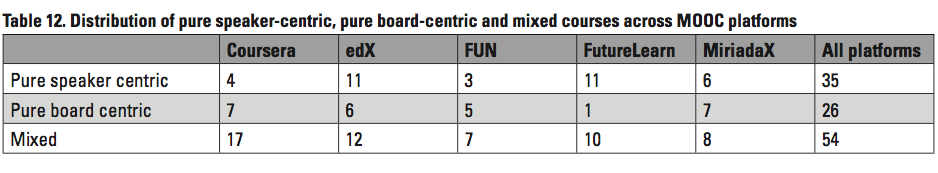

Board-centric versus speaker-centric styles

All reviewed courses make use of board- or speaker-centric videos. Only 30 courses (26%) harness styles outside the board-speaker-centric spectrum. We have searched for associations between board-speaker centricity and two aspects: the MOOC platform and the course subject area. For that purpose, every course has been labeled as serving speaker-centric videos, board-centric videos, or both.

Table 12 shows the distribution of the three course classes across MOOC platforms. Tests for independence reject significant differences between platforms, chi-squared: χ2 (8, N=115) = 13.07, p=0.109, and Fisher’s Exact test: p=0.088.

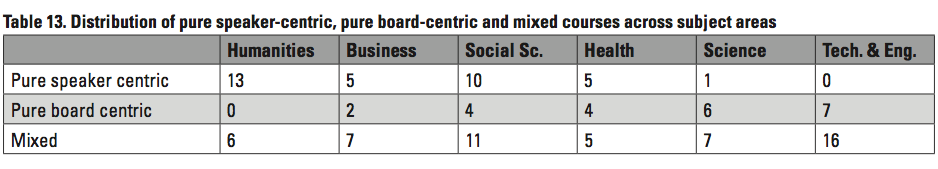

Table 13 shows how the three course classes are represented in each course subject area. The category Everyday Life was omitted, since it provides too few courses (6) and it has no representation in all platforms. A statistically significant association was found between course style approach and course subject area by using Fisher’s Exact Test: p<.0001.

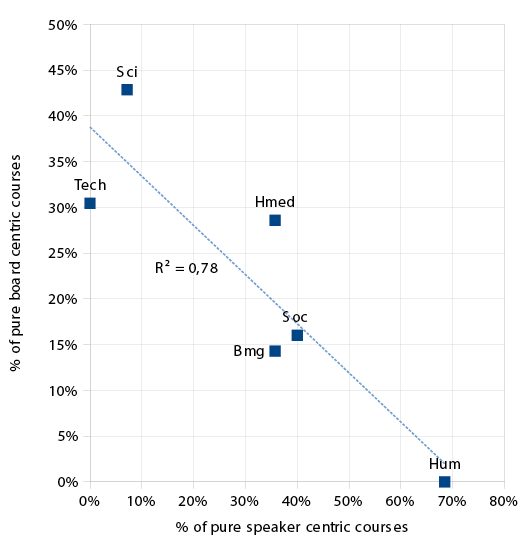

Figure 3 plots the ratio between speaker-centric and board-centric style preferences for each subject area, excluding Everyday Life. Each point (x,y) represents the x proportion of courses having exclusively speaker-centric videos and the y proportion of courses having exclusively board-centric videos. When a linear regression is applied, this speaker/centric ratio shows a high correlation (R2 = 0.78). Figure 3 also reveals a certain art-to-science cline that starts from art & humanities, passes through soft science, and ends in hard science. In this subject spectrum, humanities clearly favor speakers, hard science and technology prefer boards, and soft sciences keep an intermediate position.

Figure 3. Proportions between pure speaker centric and pure board centric courses for each subject area. The linear regression function is plotted as a dashed blue line. Hum = Arts and Humanities. Bmg = Business and Management. Soc = Social Sciences. Hmed = Health and Medicine. Sci = Natural Sciences and Mathematics. Tech = Engineering and Technology.

Discussion on Survey Results

This survey evidences a low diversity of communication styles in MOOC videos, both internal (a typical course employs two styles) and as a population. Seven styles describe the majority of courses and three of them (Talking Head, Slides, and Interview) can label more than a half of the whole sample. Some well known communication styles such as storytellings, live demonstrations, and cartoons have a testimonial presence in the examined MOOCs. Much variation of MOOC video styles can be explained with the speaker-centric to board-centric spectrum.

There are observable differences between humanistic and technological disciplines in the frequency of use of board-centric or speaker-centric videos. This relationship between speaker/board centricity and course subject may be linked to cultural factors or there may be some relation to intrinsic properties of the contents: for example, teaching about mathematical formulas or complex engineering structures may be hard without displaying equations or diagrams. That would explain part of the science and technology preference for board-centric videos. The actual source of these differences in communication styles is something to be explored in further research. Whatever the case, the advice is not to immediately generalize a research finding on the learning efficiency of instructional video styles when the research has been limited to one particular subject area.

Interpretation of MOOC Video Style Diversity

We want to finish this paper with a reflection on the systemic causes of the observed MOOC focus on Speakers and Boards videos and the observed lack of style diversity.

Many MOOCs found in generalist platforms are built from existing face-to-face courses. Usually the original course is adapted to the MOOC format, changing the interfaces and course materials but keeping the same instructional design. Most redesign effort is pushed into course assignments and discussion forums management due to the course attendance change of scale (Kellogg, 2013; Fredette, 2013).

The results from our survey are consistent with the observation that the underlying didactic technique in most MOOCs is the classic instructional lecture (Karsenti, 2013). Lectures are often adapted from the classroom to the MOOC platform with no fundamental changes, except for the audience decoupling. There are two simple approaches to accomplish this direct adaptation: one is to record your lecture talk (and edit it) and the other one is to print out your lecture notes. These two approaches lead, respectively, to the Talking Head and Slides communication styles. These kinds of videos not only are cheaper to record than other modalities but easier to design out of current conventional course material. Other communication styles and techniques; like Khan-style tutorials, storytellings, or animated demonstrations; would require more elaboration and therefore will tend to be relatively scarce in the current MOOC ecosystem. This reasoning may partially explain the distribution of video communication styles that this study reveals.

The attachment of current MOOCs to the video lecture has received criticism, as it has been acidly quoted by Ian Bogost (cited by Adams et al., 2014, p. 203): “MOOCs . . . still rely on the lecture as their principal building block. . . . The lecture is alive and well, it’s just been turned into a sitcom.” Despite the critics, the fact is that MOOCs have been successful, at least in terms of course volume and attendance. Indeed, their pedagogical conservative strategy may be one of the factors behind that success: It may have facilitated a fast transfer of educational content to the new online platforms. More disruptive or innovative approaches would have increased course production costs and, consequently, would have slowed the MOOC ecosystem growth. The production costs of MOOCs have been considerable: Hollands & Tirthali (2014) estimated a production cost ranging from USD 38,980 to USD 325,330 per MOOC. Being too innovative should lead to poor sustainability. Moreover, some tools have been created to significantly reduce productions costs. For example, Head and Slices short-length videos can be recorded and edited with the Polimedia framework (Turro et al., 2010) in almost real time with a very affordable investment.

All things considered, the conservative scenario depicted by this study may be just a sign of the early stages of a MOOC ecosystem that has been focused on the growth of course offerings, thus favoring pre-existing course reuse. It is feasible that in the near future, MOOCs will add more diversity and more innovation in their audiovisual styles as more courses will be developed free from the ties of legacy contents. Today, some may consider it ironic that one of Coursera’s courses on digital storytelling production (Coursera, 2015) is made up of slideshow videos and talking head lectures. Instead, we can view it as a natural step in MOOC evolution, in which the current system leverages its modest resources to help teachers learn new communication styles so they can build more innovative, next-generation MOOCs.

References

Adams, C., Yin. Y., Vargas Madriz, L. F., & Mullen, C. S. (2014). A phenomenology of learning large: The tutorial sphere of xMOOC video lectures. Distance Education, 35(2), 202–216.

Anderson, T. & Dron, J. (2011). Three generations of distance education pedagogy. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(3), 80–97.

Coursera. (2015). Powerful tools for teaching and learning: Digital storytelling. University of Houston System. Retrieved from https://www.coursera.org/course/digitalstorytelling.

Fredette, M. (2013). How to convert a classroom course into a MOOC. Campus Technology. Retrieved from https://campustechnology.com/Articles/2013/08/28/How-to-Convert-a-Classroom-Course-Into-a-MOOC.aspx

Giannakos, M., Jaccheri, L., & Krogstie, J. (2014). Looking at MOOCs rapid growth through the lens of video-based learning research. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 9(1), 35–38. doi: 10.3991/ijetv9il.3349

Goodyear, P. M., & Steeples, C. (1998). Creating shareable representations of practice.

Research in Learning Technology, 6(3), 16–23.

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos. Proceedings of the First ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale Conference (L@S’14), 41–50.

Hansch, A., Hillers, L., McConachie, K., Newman, C., Schildhauer, T., & Schmidt, P. (2015). Video and online learning: Critical reflections and findings from the field. HIIG Discussion Paper Series No. 2015-02. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2577882

Hollands, F., & Tirthali, D. (2014). Resource requirements and costs of developing and delivering MOOCs. The International Review Of Research In Open And Distributed Learning, 15(5), 113–133.

Karsenti, T. (2013). The MOOC. What the research says. International Journal of Technologies in Higher Education, 10(2), 23–37.

Kay, R. H. (2012). Exploring the use of video podcasts in education: A comprehensive review of the literature. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(3), 820–831.

Kellogg, S. (2013). How to make a MOOC. Nature2, 499, 369–371. doi: 10.1126/science.7939709

Kizilcec, R. F., Papadopoulos, K., & Sritanyaratana, L. (2014). Showing face in video instruction: Effects on information retention, visual attention, and affect. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’14), 2095–2012.

Koumi, J. (2006). Designing video and multimedia for open and flexible learning. New York: Routledge.

Liyanagunawardena, T. R., Adams, A. A., & Williams, S. A. (2013). MOOCs: A systematic study of the published literature 2008-2012. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning,14(3), 202–227.

Moes, S. (2012). REC:all Framework. Retrieved from http://www.recall.info/profiles/blogs/definitions-of-various-formats-of-captured-lectures-inrelation

O’Donoghue, M. (2013). Educational video: A literature based educational thinking tool for student and teacher production. EdMedia: World Conference on Educational Media and Technology, 2013(1), 902–909.

Majid, S., Khine, W.K.K., Oo, M.Z.C., & Lwin, Z.M. (2012). An analysis of YouTube videos for teaching information literacy skills. In Thaung, K.S. (Ed.), Advanced Information Technology in Education (Vol. 126), 143–151. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Ploetzner, R., & Lowe, R. (2012). A systematic characterization of expository animations. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(3), 781–794.

Rodriguez, C. O. (2012). MOOCs and the AI-Stanford like courses: Two successful and distinct course formats for massive open online courses. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 2.

Santos Espino, J. M., Afonso Suárez, M. D., Guerra Artal, C., & García-Sánchez, S. (2013). Measuring the quality of instructional videos for higher education. 6th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (ICERI2013).

Schwartz, D. L., & Hartman, K. (2007). It is not television anymore: Designing digital video for learning and assessment. In R. Goldman, R. D. Pea, & S. J. Derry (Eds.), Video research in the learning sciences (pp. 335–348). New York, NY: Routledge.

Shah, D. (2015). By the numbers: MOOCs in 2015. Class Central. Retrieved 6 January, 2016 from http://www.class-central.com/report/moocs-2015-stats/

Swarts, J. (2012). New modes of help: Best practices for instructional video. Technical Communication, 59(3), 195–206.

ten Hove, P., & van der Meij, H. (2015). Like it or not. What characterizes Youtube’s more popular instructional videos? Technical Communication, 62(1), 48–62.

Thornhill, S., Asensio, M., & Young, C. (2002). Video streaming: A guide for educational development. The JISC Click and Go Video Project, ISD, UMIST.

Turro, C., Cañero, A., & Busquets, J. (2010). Video learning objects creation with Polimedia. Proceedings – 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia, ISM 2010, 371–376. http://doi.org/10.1109/ISM.2010.69

Udell, J. (2005). What is screencasting. Retrieved from http://archive.oreilly.com/pub/a/oreilly/digitalmedia/2005/11/16/what-isscreencasting.html

Yousef, A.M.F., Chatti, M.A., Schroeder, U., & Wosnitza, M. (2014). What drives a successful MOOC? An empirical examination of criteria to assure design quality of MOOCs. 2014 IEEE 14th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT).

About the Authors

José Miguel Santos-Espino is an associate professor at the Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Spain). He teaches courses on computer science and software engineering. His current research interest is the learning effectiveness of educational videos. Contact: josemiguel.santos@ulpgc.es

María Dolores Afonso-Suárez is a licensed fellow researcher of the Instituto de Sistemas Inteligentes y Aplicaciones Numéricas en la Ingeniería (SIANI) at the Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. Her research interests include the engineering of multimedia learning objects. Contact: marilola.afonso@gmail.com

Cayetano Guerra-Artal is an associate professor of Computer Science at the Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria since 1999. He has been involved in a number of information technology-based educational projects. His main topics of interest include multimedia and video production for education and design of software tools for education. Contact: cayetano.guerra@ulpgc.es

Manuscript received 28 October 2015, revised 3 February 2016; accepted 15 February 2016.