Abstract

Purpose: This article asks what can be learned about knowledge flows in the field of technical communication from the networking activities that independent entrepreneurs use to learn relevant information, influence practice, and build professional conversations.

Method: The article uses qualitative methods informed by theories of social network analysis to examine interview data collected from eight successful technical communication entrepreneurs.

Results: Technical communication entrepreneurs actively publish and read publications to learn relevant information about the field, influence practice, and build professional conversations. Academic publications are often outside these entrepreneurs’ scope of interest because of differing timescales, venues, and key terms; however, they often read publications of and publish toward the professional networks generated as they connect with others for business interests.

Conclusion: The field must continue to find ways to bridge academic and practitioner divides by seeking common venues, shared timelines, and collaborating on emerging topics of interest. However, these divides are more complex than simply among academics and practitioners, as knowledge flows in the field have become multidirectional rather than two-sided.

Keywords: networking, entrepreneurship, publication, research, social networks

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Technical communication entrepreneurs network to learn relevant information, influence practice, and build professional conversations.

- Professional social networks are central to how knowledge is shared and circulated in the field.

- The field of technical communication includes a variety of influencers who work across multiple timescales, communicate in different venues, and engage with divergent key terms as they build knowledge about practice.

- There are a number of ways academics and practitioners can find common ground to learn from each other’s research, such as connecting on social media, attending conferences and meet-ups, and collaborating on relevant, mutually beneficial projects.

Introduction

For quite a while now, the field of technical communication (TC) has questioned whether its academic research is accessible to practitioner audiences. Yet, this essential question tends to overlook that TC’s knowledge flows are not unidirectional. That is, both academics and practitioners produce discourse that actively shapes what technical communicators know and do, but this discourse can seem unfortunately relegated to separate silos. Anecdotally, academics and practitioners express resentment over this divide, though both groups likely pay inadequate attention to the other’s growing and emerging knowledge base. This divide, too often, results in a lack of collaboration and cooperation on research efforts, even though working together would likely yield a great deal of value.

The concern about an unproductive divide between TC academics and practitioners has been well documented in several areas of the field’s research, particularly in how academics approach instructional techniques in the classroom. Meanwhile, discussions related to how the field establishes theory appear to be relatively lopsided in favor of academic conversations. Rebekka Andersen (2014) describes this problem in her recent discussion of the development of content management (CM) knowledge in TC, in which she notes that researchers “have not done a good job directly engaging in the robust and extensive CM conversations taking place outside of the academy” (p. 117). By directly attending to these industry conversations in her article, Andersen positions industry “thought leaders” as crucial knowledge-makers with valuable ideas, resources, and technologies that academics must take seriously (p. 116). But, where do industry leaders’ conversations exist? How and where can academic and industry discourses come into dialogue?

In this article, we address the divide between academics and practitioners by describing how TC entrepreneurs access, learn, and disseminate relevant information. To do so, we report on a portion of a recent qualitative research project analyzing the professional social networking practices of TC entrepreneurs. In the project, we interviewed eight technical communicators who own independent or small businesses. The results indicate in what ways participants felt the knowledge flows in TC were fractured, with little practitioner knowledge and research represented in academic work. However, results reported in this article also address the special issue theme by providing rich examples of the multidirectional flows of information that TC entrepreneurs access and influence. We believe that understanding these professional networks and the infrastructures that support them can provide opportunities for more engagement across the field’s traditional silos.

Below, we review literature on the academic-practitioner divide and the state of current publishing practices. Next, we describe how the study used qualitative interviews and a grounding in social network theory to better understand the social ties and practices that support independent TC work. Based on this theoretical context, we identify networking practices that TC entrepreneurs use to create and disseminate useful knowledge before reporting on the conferences and venues where this work happens and its relationship to academic and industry spheres. Building from these findings, we argue for the important role that TC entrepreneurs can play in bridging academic and industry domains and offer preliminary ideas for increasing interaction among TC’s various knowledge networks. Specifically, we suggest that the field reconsider the importance of its multiple influencers, multiple timescales, and multiple venues or communication infrastructures. In order to become more connected, academics and practitioners can build on shared venues, times, and terms, but doing so will entail confronting challenges similar to those that have historically separated academics from practitioners.

Literature Review

As a result of organizational and individual work to develop a rigorous disciplinary TC research agenda, the field now has a well developed understanding of constraints that have limited academic research in TC. Academic research has been historically shaped by faculty members’ individual academic tenure requirements, their struggles to legitimize TC research methods and approaches within English departments, and the challenge of finding adequate research support given the field’s diverse methods and lack of training for developing researchers (Rude, 2014; Lam, 2014; Blakeslee, 2009). In particular, Barbara Mirel and Rachel Spilka’s 2002 collection examined academic-practitioner divides and helped the field understand how and why collaborating with industry professionals is not always valued given the constraints many TC faculty face. Mirel and Spilka argued that these constraints not only hindered the ability for academics and practitioners to effectively collaborate but also reinforced fragmentation that affected the field’s potential influence. Thus, the field needs “strategic planning and decision making” to extend technical communicators’ voices “beyond publication departments” (Mirel & Spilka, 2002, p. 4).

Various industry-academia collaborations were posited as the most practical way out of the divide, including activities such as internships, usability studies, short-term research, and curricular advisory boards. However, contributors also maintained compelling arguments for why academic-practitioner divides are culturally systemic (Dicks, 2002) and may even be necessary to retain the traditional goals of public education (Bernhardt, 2002). Generally, however, contributors in the collection argued for a move away from understanding knowledge flows as deriving either from academia toward industry or from industry toward academia, seeing instead the possibilities for a “two-way reality” (Rehling, 2004, pg. 92) that would build on the best of what each domain had to offer. In order to embrace this multi-directional knowledge base, for example, Shriver (2002) advocated for academic researchers to alter their dissemination practices to create writing that can not only reach practitioner audiences but also position itself for uptake by stakeholders in the public sphere.

In the years since Mirel and Spilka’s collection, constraints on academic research have no doubt continued to influence research design, exigence, and credibility in academic discourse. However, it is now possible to see diversity across TC’s peer-reviewed journals that include a push for more research that is both rigorous and applied (Carliner et al., 2011). Importantly, the years since Mirel and Spilka’s collection have also brought changes to models of scholarly TC publication. For instance, academician Clay Spinuzzi (2013) and industry professional Richard Sheffield (2009) both self-published well-respected books aimed at academic and industry audiences. Recently, the MIT Media Lab launched the Journal of Design and Science (http://jods.mitpress.mit.edu), which is “hosted on an open-access, open-review, rapid publication platform” (About, para. 3) as a means to rethink ways of peer reviewing and collaborating across diverse fields, including, perhaps, counterparts in industry. These shifting dynamics are evidence of slowly changing cultural attitudes toward publication, offering new options for exploring dissemination in ways that Shriver (2002) suggested were necessary. As well, some historically prevailing expectations about publication within the humanities have shifted with the increasing importance of digital humanities and computers and writing venues, where digitally born texts are being published at academic venues such as Enculturation, Present Tense, and Kairos. Meanwhile, social networking sites like LinkedIn and Twitter enable practitioners to share links to a range of publications with varying ease (e.g., links to professional blog posts, newsletters, and articles). Additional open-access examples in digital circulation seem to appeal to both academic and industry professionals in TC, such as TC World and User Experience Magazine.

From the practitioner side of the “two-way reality,” practicing technical communicators are increasingly likely to work outside of publication departments in a range of positions with different names and expectations. They are also likely to spend part of their careers working independently as contractors, consultants, or in some form of self employment. While traditional technical writing positions in corporations still exist, of course, many practitioners chart a different kind of career course through work with multiple firms that may lead to different cultural dynamics and expectations than those that Dicks (2002) described as forming the attitudes that shape practitioners’ likelihood to work with academics. In terms of publication and writing, technical communicators are also likely to extend beyond traditional internal publication formats. Many are using blogs, social media, and other social networking sites to connect with current and future clients and employees (Ferro & Zachry, 2014). For example, Blythe, Lauer, and Curran (2014) use survey research to suggest that the forms of writing that graduates of professional and TC programs value most in their lives include not only instructions, manuals, and presentations but also emails, websites, and blogs (p. 273).

These emerging communication infrastructures provide intriguing platforms for academics and practitioners to interact and discuss research. It seems as if these platforms are, in some circles, already being actively used. Whether those circles enable interactions that cross the academic-practitioner divide remains unclear, however. In the research project we further outline below, we illustrate how entrepreneurs in TC engage with research, learn, and disseminate information to others. The next section of this document addresses our study’s research methods and preliminary results.

Studying the Networks and Networking Practices Supporting TC Entrepreneurship

This article expands on a portion of results from a larger research project (see Lauren & Pigg, in press) that studied how entrepreneurs in TC engage with personal and professional social networks to build and sustain their careers. Central findings of the research describe how participants used networking for activities that have been described as central to independent work, such as learning to run a business (Poe, 2002), marketing to attract clients (Broach et al., 2006; Killoran, 2010), or obtaining legal advice (Glick-Smith & Stephenson, 1998). To further clarify, in this article, we more closely examine the activities participants engaged when producing, finding, and circulating useful and relevant professional information for the broad field of TC (e.g., from content strategy to product documentation). With this focus in mind, we revisited our existing data with newly refined research questions:

- What networking practices enable TC entrepreneurs to access and share relevant professional knowledge?

- Which network ties are most relevant to TC entrepreneurs’ practices of accessing and sharing professional knowledge?

- What opportunities and challenges do these networking practices and ties create for research collaborations and exchanges among TC academics and practitioners?

Using these research questions as a guide, we focused our analysis on the specific portion of the data that helps to describe how TC entrepreneurs’ professional social networking activities influence how information, such as research, is accessed and shared.

Research approach and theoretical framework

Despite strong anecdotal evidence suggesting ongoing growth in independent labor (i.e., contracting, consulting, and business ownership), research on practices of TC entrepreneurship has been surprisingly limited. As evidence of independent work, industry support structures were long ago created, such as the independent consulting and contracting special interest group of the Society for Technical Communication (STC). In addition, a special issue in Technical Communication has addressed the topic (Barker & Poe, 2002) and the STC has gathered and shared data on the phenomenon (STC, 2004; STC, 2005). Given the limited research on TC entrepreneurs, we developed qualitative interview research to provide descriptions of entrepreneurs’ social networks and networking practices and to serve as a starting point for additional inquiry. While limited in terms of generalizability, interview studies and in-depth qualitative research are useful in such cases for evoking themes and details that can be further explored in later, larger-scale studies.

Our qualitative data collection and analysis procedures in this study were informed by concepts that emerge from interdisciplinary theories of social network analysis (SNA). Broadly, SNA directs researchers’ focus to the importance of social relationships that shape potential social action, attending in particular to how relationships between individual actors create structures through which resources and forms of capital are shared and circulated (Scott, 2013; Wasserman & Faust, 1994). With its focus on how relationships are created and sustained, it is no surprise that SNA has a strong tradition in the scholarship of entrepreneurship studies, where business success depends upon social connections and embeddedness (Greve, 2003; Dubini & Aldrich, 1991). While much SNA research in entrepreneurial studies has consisted of quantitative tracing to determine how entrepreneurs monetize networks toward venture success, recent scholarship has called for qualitative analysis to analyze the quality, cultural relevance, and value of entrepreneurial networks (Slotte-Kock & Coviello, 2010; Jack, Drakopoulou Dodd, & Anderson, 2004). We position our research in this vein: We have conducted qualitative case research conceptually grounded in network theory, building on its key ideas to generate relevant qualitative details.

To explain, we next define key concepts that ground SNA studies and compare our approach to other research in TC. Key concepts within SNA include actors, or individual social units; links, or the relationships that connect actors; and structures (also called networks, fields, or environments), which are the relational units that result from multiple connections among individual actors (Scott, 2013; Wasserman & Faust, 1994). In addition, because our participants choose to work independently and our larger project focuses on how they build and sustain careers, we build on the SNA concept of egonets, or social networks that form around individuals (Rainie & Wellman, 2012; Wellman, 1993).

We drew on these concepts in our interview protocol by first positioning each interviewee as a central actor—the focal point of the egonet—and then designing questions to elicit their descriptions of the most relevant social actors (i.e., people and organizations) influencing their careers. By mapping these relationships, we were able to better understand the social fields that individuals perceived around their work, as well as to understand the communication and technology infrastructures (i.e., platforms, professional social groups, personal social groups) that supported their development. By relying on self-reported personal network data in a form that invites thick qualitative detail rather than precise quantitative tracing, our approach is related to but differs from similar prominent work in TC that uses SNA approaches. For example, Read and Swarts (2015) examine textual artifacts that mark a prior work trajectory to reconstruct links among relevant actors in particularly generative moments of knowledge work, and TC scholarship has also employed quantitative structural network tracing to map the effects of communication links on knowledge work (Burton et al., 2012). To contrast, our research uses SNA concepts to draw out details and descriptions, because our goal is to generate themes that can ground further research.

Participants, data collection, and analysis

Between November 2015 and January 2016, we conducted interviews with eight individuals who affiliate with the field of TC and who own small businesses or intentionally work as independent contractors. In recruiting participants, we recognized that significant differences exist between the experiences of consultants and contractors (Ames, 2002) and that not all contractors or consultants purposely choose to work independently. However, we chose to study independent work with well-established entrepreneurs to understand how they achieved success. During the interview period, participants represented geographical regions across the United States, Canada, and Central Europe. Participants were also evenly distributed across male and female genders. Though most participants in the study did not use the term technical communication in their company names or job descriptions, all perceived themselves to be conducting work that could be considered within the domain of the field. Their self-identified job titles were as follows:

- Participant 1: User experience consultant

- Participant 2: President, principal/owner, and only consultant of company

- Participant 3: President and owner of content strategy company

- Participant 4: Consultant and contracted technical publications manager

- Participant 5: Content strategy consultant

- Participant 6: President, principal/owner, and only consultant of company

- Participant 7: President and only consultant of company

- Participant 8: President/executive in small business (former CEO)

Interview questions positioned participants as central social actors and gathered participants’ career narratives while prompting them to name other relevant social actors that shaped their careers at various points in time (i.e., during their education, during different moments of their employment history). Interviews were conducted via Skype and ranged from around 100 minutes to around 200 minutes, with most lasting around 120 minutes. After completing interviews, we transcribed and segmented them by conversational turns (i.e., by speaker). We began data analysis by coding interviews to identify networking ties, networking practices, and networking technologies that were named, as well as for factors shaping decisions to work as an entrepreneur. Next, we conducted a second coding pass to categorize and characterize networking ties, practices, and technologies, and to create data visualizations of participants’ egonets (i.e., personal networks) as derived from interview data. Through collaborative memoing, we developed narrative interpretations of findings.

Results

Our findings explain the various ways participants actively create, find, and circulate information to advance professional knowledge in TC. While most of these activities would not be considered research by the standards of university institutional review boards, they provide insight into the communicative and technological infrastructures that support the development of practitioner knowledge over time. Through activities such as maintaining a social media presence, reading and publishing in venues affiliated with professional organizations, and presenting at conferences, our participants gain access to knowledge and help develop it. Dicks (2002) suggested that academics and practitioners are divided by disparate perceptions about information, where academics tend toward sharing information to advance knowledge and industry professionals protect it for company profit. However, our participants blur these information sharing boundaries because they often work outside the culture of a single organization and are invested in building individual social capital to sustain business into the future. As a result of this shift in objectives, information-sharing practices become a central activity in their work. We discuss these practices through a focus on three motivations for reading and publishing: learning, influencing, and building.

How TC entrepreneurs network to learn

Participants reported being invested in looking outside corporate environments for information that can help solve day-to-day problems or gain expertise needed to take on new projects. This finding aligns with Thomas Barker and Kathryn Poe’s (2002) description of independent TC workers as lifelong learners who need to continually “extend their expertise or education” (p. 152). For instance, all participants described attending professional meetings and joining professional organizations as avenues for gaining access to relevant information. Participant 1 described his selection of professional organizations in this way: “I usually take a couple hundred bucks each year and I pick a semi-random professional organization and I give them my money for a year, right? And then that gets me their newsletter, their journals.” Professional organizations were of central importance to determining the kinds of publications participants read and regularly accessed. Many were unlikely to go out in search of published research except when they needed to learn something specific for a project but were very likely to read things that were “pushed” to their inboxes by a professional organization when they determined over time that the organization had meaningful information to offer. In this way, social media not only provided access to people but also enabled mechanisms for filtering information so that participants received information that was immediately relevant to them. Participant 2 suggested, “I have [LinkedIn] set to pull all of the relevant stuff from a couple of discussion groups and they push that to my inbox. I don’t go out and look for it.” Ease and convenience of accessing information was therefore an important factor for how our participants engage in learning activities.

Participating in professional meetings was also an avenue for meeting people who became important ongoing, durable information resources. At conferences, often through professional organizations, participants connected with individuals to find relevant information. Then, social media would be used to help strengthen and maintain those connections. For example, Participant 1 explained “conferences [are] a form of semi-formal education” and discussed how social media became a way to extend conversations begun in more traditional venues:

I [use Facebook] to stalk them a little bit and say oh they’ve joined a new company now. I didn’t know that, right? I thought they were in New York City and now they’re in LA. Well, that’s my excuse to learn a little bit more about them.

Five of our eight interviewees noted the importance of just chatting with other professionals as a central way to learn and gain access to new information, whether through local face-to-face meetups or social media use. Participant 5 illustrates “chatting” online in this way: “I know people all over the world because of all these conferences, and so on, and we all follow each other, and we all exchange comments, barbs, information, useful tips, etc. And sometimes we debate.” A great deal of information sharing and learning seems to take place at conferences specific to practitioner audiences, and these conversations continue online through social media.

How TC entrepreneurs network to influence

While participants were invested in learning from others, they also actively sought to influence the field by contributing to existing conversations and seeking to begin new ones. All eight participants described speaking in public—particularly at professional conferences—as a key way to influence others. Participants considered these activities to be influential because they enabled them to change how others conducted their work. Participant 2 explained,

I speak at a lot of conferences. There are people that I’ve affected that I have no idea who they are, because they were 1 of 50 people sitting in a room. They may never say anything to me but they’ve changed. Something I said changed how they looked at their work.

Many of the participants were also prolific authors of influential books and articles. For example, seven of the eight participants discussed how important producing professional publications had been for advancing their careers. The goal of publishing was rarely to theorize TC; instead, publications were to help others get work done. Participant 6 explained how this method of influencing functioned as a way to sustain business but also as a way to influence how the field works. For instance, Participant 6 said,

A lot of companies bought my book and had it in their library. And so for example [software company] solicited me to come there and give them a lecture to their user interface group and tech comm and online help and media and game development people. And that was based on just having my book.

Publishing helped created avenues of influence that had not previously existed but also led to building and maintaining relationships with other professionals.

Building relationships locally—both in geographical regions and across professional subgroups—was also important to how participants sought to influence knowledge in TC. At times, relationships were built as a means for bridging subgroups in industry that did not often engage with each other. These participants acted as ambassadors for the field, working to create less stratification and bridge divides that exist across industry divisions as well as between industry and academia. To illustrate, Participant 6 argued,

Many people in design don’t know the people in writing, and the people in writing don’t know the people in design. And so there’s a suspicion there and practitioners don’t necessarily know the researchers and the researchers don’t necessarily know the practitioner side. I tried in my own small way to contribute to helping people see each other’s perspectives.

Other participants also focused on using influence to increase the status of their work in their geographical regions. Participant 1, for example, worked diligently to bring user experience concerns to the Midwest, whereas Participant 2 purposefully networked with e-learning and instructional design professionals in the Mountain West to increase dialogue among TC and these fields. These relationships also provided instances for sharing information across TC subfields.

Participants additionally sought to influence professional knowledge by circulating and curating ideas using less formal platforms. While many participants reported keeping professional websites and portfolios in line with those discussed in recent scholarship (Killoran, 2011, 2012), six of eight of the sample discussed writing blog contributions to disseminate relevant information. Some participants kept personal/professional blogs, whereas others used public aggregation and circulation technologies such as Longform or Medium. In a discussion about diversity, for instance, Participant 8 noted, “I plan on writing some very serious, intense essays on diversity in the technology sphere using Medium.” In addition to blogging, participants influenced others by curating and contributing discourse to Twitter and LinkedIn. Participant 2 explained, “I’ll have a reading day or something and I’ll read 6 or 7 articles and I’ll tweet about all of them.” These activities also seemed to support building the kinds of infrastructures many of the participants sought to construct both to further their careers, but also to advance knowledge in the field.

How TC entrepreneurs network to build conversations

TC entrepreneurs were not simply learning and influencing; they were also building new conversations across platforms, organizations, and relationships that actively expanded the reach of TC as a field. In many ways, Participants were working to identify best practices and/or create spaces for the profession where it had not previously existed. For example, Participant 1 discussed a recent alliance with a local art museum that enabled him to share his information architecture expertise but that also required him to learn more about visual literacy. Participant 1 explained, “The most educational parts for me are when I’m organizing something, so like organizing a workshop, right?” Many participants had been (and still are) leaders in professional organizations and working groups, and, in that leadership capacity, sought to build networks and frameworks for independent TC, information design, interaction design, information architecture, user experience, Web standards, international writing studies, and plain language—just to name a few. In short, to influence, participants built formidable careers.

As such, several participants identified as “thought leaders” and used their influence to maximize positions in professional organizations and educational groups. Participation in these organizations and groups also helped them build new conversations while sustaining business interests. For example, Participant 8 described it this way:

[Part of my job is being a] thought leader and so I spend an incredible amount of time on the road speaking, right? That’s why I . . .I’m on the road speaking giving talks all the time, which is also lead generation and a variety of other things. We give master classes 2 or 3 times a year in different parts of the world.

Notably, Participant 8 described being a thought leader as connected to educating others. In other words, being a thought-leader is about what she knows and does rather than simply working to attain more business. As Participant 8 described, “I don’t like selling, so the funny thing is that I end up selling through education, right? People go and listen to me talk. So I am selling, but I am selling by being a thought-leader.” The recursive nature between the role of thought-leader and entrepreneur is important to how spheres of influence are built and information is communicated.

Industry thought-leaders share a complex relationship with the financial demands of industry and the constraints of conducting and communicating what academics consider systematic, rigorous research. Participant 6 provides an interesting case that demonstrates this relationship in practice. Participant 6 is a prolific researcher and frequent research reviewer and believes that industry wants research results rather than to fund research. Participant 6 explained,

Many of the kinds of things that people want me to do don’t necessarily involve research. What they want is for me to bring the research to them, and to help them use the research on the spot, at the exact moment I walk in.

As a result, Participant 6 works to

use my money that I get from consulting to fund my own research because [when] I used to try to frame up the research for clients and see if they would pay for it, that was met with mixed results because they usually didn’t want to pay for any research. They just wanted it, and wanted it for free.

Using consulting money to fund independent research is important because it shows another example of the recursive relationship between being a thought-leader and an entrepreneur. In terms of process, Participant 6 uses the following strategy:

I like to use my practical projects as a kind of an intellectual engine to get my juices going to think about problems people are really having and ask the question how does what they’re interested fit into what I’m interested in and could I write something that would be interesting to both academics and people who are practicing in the field.

This broad appeal also suggests Participant 6 bridges the gap between industry and academia in productive ways, building new conversations while also sustaining personal financial interests.

Networking ties relevant to accessing and sharing information

Participants’ networking ties—the individuals and organizations with whom participants connected—can help clarify who participants understood as most relevant to sharing and gaining professional knowledge. To what extent are academics and industry thought leaders in dialogue in the conferences, blogs, Twitter, and LinkedIn conversations that TC entrepreneurs referenced? Which professional organizations and conferences did TC entrepreneurs find most meaningful? To understand participants’ relationships to academic domains, it is useful to understand that their positions blurred boundaries between industry and academia. Most participants held an academic role as a part-time or visiting faculty member or industry liaison. These positions, in some cases, led them to question whether, in Participant 6’s words, “maybe we’ve made too strong of a distinction between [academic and industry] and that people think that you are either this or that.” Yet, all participants detected and described a persistent gulf between TC academic and practitioner interests, even referencing the scholarly conversations as moments of lost opportunity for advancing the field. For example, Participant 6 argued, “it seems as though the gulf between the academic world and the practitioner world has increased even though Rachel Spilka and Barb Mirel did their book 10 or 15 years ago.” Other participants expressed concerns that academics who have “been in the system too long” lose touch with how the business world works and struggle, when given the opportunity, to effectively lead professional organizations in TC (Participant 4).

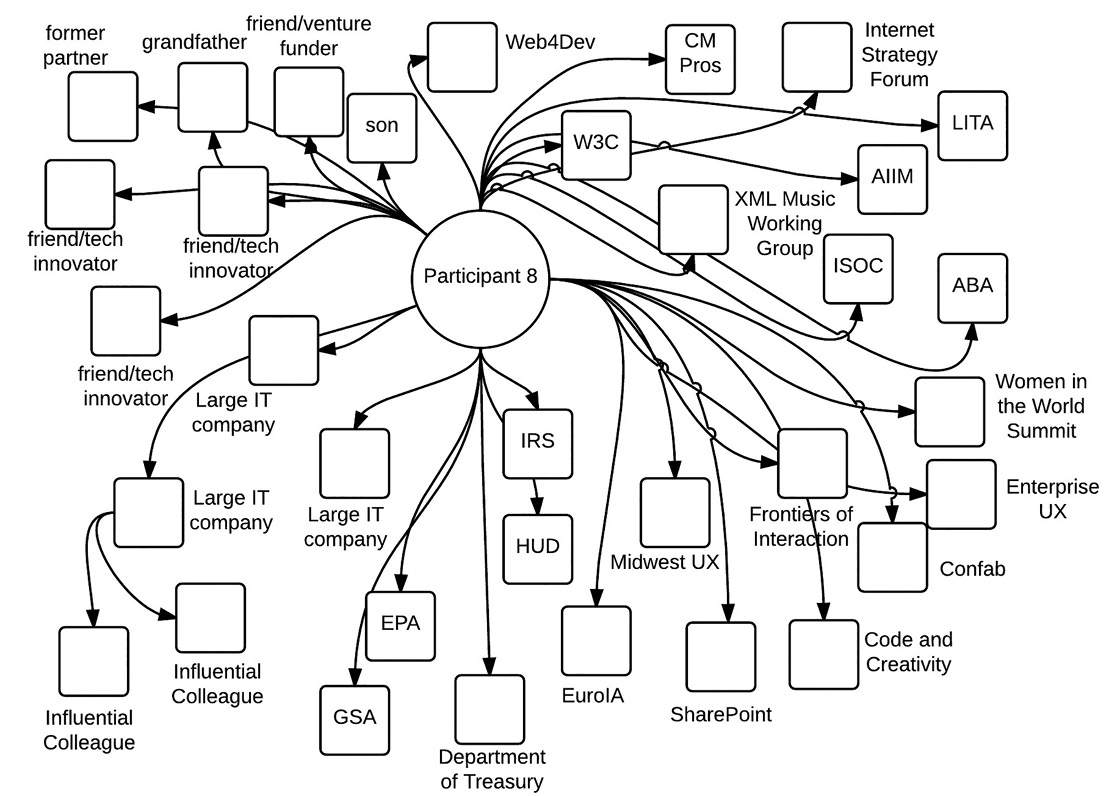

A closer look at the social ties participants understood as most relevant to learning, influencing, and building reveals potential tensions between TC’s academic research dissemination and its entrepreneurs’ needs and practices. To provide one example of these disconnections, we detail in the following section an egonet analysis of Participant 8. Participant 8’s case reflects the larger sample because of the importance she places on professional organizations (and many of them). It furthermore challenges academics and practitioners to consider the scope of relevant venues where TC knowledge is exchanged. Participant 8’s case also suggests alternative routes through which professional affiliations with the field can evolve.

Case example: Participant 8

Participant 8 attended two post-secondary institutions and credits her mentors in those institutions as helping her find a passion for semantic logic, critical thinking, and problem solving. Participant 8 believes these interests ultimately positioned her well for working with the development of the Internet and World Wide Web. After her undergraduate degree, Participant 8 entered graduate school at a prestigious private US institution with the goal of becoming a college professor but left the program on the advice from a mentor who suggested she move to Silicon Valley for a part-time job coding HTML at a prominent IT company. She later left this coding job to work full-time in a different prominent IT company. Eventually, she left this job as well to begin a small consultancy because of a combination of personal and professional factors. A mentor in the last IT company where she worked suggested that she was well suited for management around the same time that she realized industry work hours were limiting her ability to parent in the way she desired.

Figure 1 illustrates the individuals and organizations Participant 8 referenced in response to questions about relevant social resources supporting independent work. Academic ties did not extend beyond her graduate school education, and she was not influenced by TC’s academic research culture nor by the professional organizations known for bringing together TC academics and practitioners. While Participant 8 does attend academic conferences, she seeks out affiliations with the legal community and library and information sciences (e.g., the American Bar Association and the Library and Information Technology Association) because of their implications for online information management. By contrast, as Figure 1 additionally illustrates, Participant 8 has been very active in a range of working groups driven by government, industry, and professional practitioners (e.g., the Internet Strategy Forum, Internet Society, Web4Dev, Confab). These groups and conferences span the research and practice of information literacy and management, user experience, content strategy, information architecture, Internet strategy, and standards and governance. She also networks with Internet developers, women entrepreneurs, and many others. Participant 8’s connections to TC developed through relationships fostered in the user experience and information architecture and management communities.

Discussion

Building from Participant 8’s career trajectory and interconnectedness with various professional organizations and venues as a case example, we now broaden our conversation once more to discuss what’s challenging about the communication of research among academics and practitioners by focusing on challenges of venues, timescales, and terms.

The challenge of venues

From Participant 8, we can see a number of challenges for the possibility of academic-practitioner interaction: They often share information in separate formal venues. Many of the conferences and working groups that Participant 8 frequents might be considered out of TC’s knowledge boundaries and infrastructures while also being cost prohibitive for academics. This was a concern across the sample. For example, Participant 7 explained that “academics don’t have the budget for the work that I’m doing” and he’s therefore unlikely to seek out conferences they attend. Practitioners and independent workers may also prefer oral venues (i.e., just chatting) for exchanging ideas because of the legal complexities of publicly sharing work affiliated with major corporations, even when independents retain authorship (Killoran, 2011).

The challenge of timescales

While this was less a concern for Participant 8, many participants echoed a resonant theme from earlier literature on the academic-practitioner divide: that TC academics and practitioner exigencies do not work on the same expectations about time. For example, Participant 2, who holds a master’s degree in TC, described joining the IEEE Professional Communication Society to fulfill the requirements of a position but did not continue her involvement because

with the academic organizations I felt like I was doing a lot of contributing and not getting a lot of information back from them. And part of that is because I operate—[my] business operates—on a completely different timescale from academia.

Where academia is “slow moving” and includes “a lot of deep dives into things,” Participant 2 said she chose against an academic career precisely because she doesn’t “want to be down there in the trenches doing the research.” Instead, she suggested, she wants to “benefit from the results of it” in a way that is responsive to the reality that “I move at a different speed.” Participant 4 says, “the stuff in the journal can be important but for the most part I don’t care because it doesn’t have any direct effect on me.” These cultural expectations echo Dicks’ (2002) explanation of why industry/academic collaborations often fail, because “academics believe in investing in the future” through slowly developing research and “become disappointed or discouraged” by the more short-term needs of practitioners (p. 17).

The challenge of terms and identities

The final challenge that Participant 8’s discussion raises for the productive exchange among academics and practitioners is one of terminology and identity. Participant 8 understood her work to be within the TC umbrella but was much more likely to use terms such as information management, content strategy, and user experience to discuss her work and, as a result, participated most in venues that foregrounded these terms. The data indicated this was overwhelmingly the case with TC entrepreneurs, even with participants who were more connected to the Society for Technical Communication. For example, Participant 4, a long time STC member and independent contractor, suggested,

One of the STC’s problems is that we call ourselves the STC and the problem is that nobody thinks of themselves as technical communicators. They think that that’s something that their parents did. But they are content specialists or information architects or you know any of another dozen titles, all of which really say technical communicator but they don’t understand it and the differences. And you know you stack all of these titles up and . . . 99 out of 100 it’s a distinction without a difference, but you can’t tell them that.

Issues related to terms and identities seem to indicate the field has grown more amorphous and complex as it has developed over time. The broad TC umbrella as a term or identity for those engaged in emerging work, however, appears to remain problematic.

Conclusion: Opportunities for New Connections

Rather than illustrating a “two-way reality” between academics and practitioners, the knowledge flows of TC are becoming more multidirectional. Practitioners do not belong to a simple homogenous category, and, of course, academics do not either. TC consultants, contractors, and small business owners often occupy space between industry and academia as they contract work, publish as influencers or thought leaders, and in some cases conduct and review systematic research as well (such is the case for Participant 6). The participants in this study also affiliated with practitioner and industry professional organizations not always accessible for many academics. If TC, ten years ago, was focused on trying to assemble two sides of a coin, it now faces the challenge of bringing together multiple knowledge networks shaping theory and practice. A fully interconnected field may not be possible or even desirable under these circumstances. However, improved strategies for bringing the field’s many discourses into conversation might start with first recognizing the multiple kinds of influencers in the field. Furthermore, we can learn from the field’s independent workers, who already think and act across boundaries of knowledge and practice. To further discuss what opportunities might be possible across the multi-directional knowledge flows of TC, we return to the challenges of venues, timescales, and terms/identities to conclude our discussion.

Shared venues online

Professional organizations and meetings still provide an opportunity for the exchange of discourse among academics and practitioners. However, seeking out more informal venues may provide a viable option for exchanges across traditional divides. Participant 6 suggested that academics must find middle ground between academia and industry, through “ways to promote [ideas] to a mass audience, whether that would be on a venue like LinkedIn or on Twitter or through technical reports or newspaper articles or magazine articles or popular journal articles.” Participants often modeled these contributions by participating (reading, commenting, and referencing) in informal online exchanges.

Academics can take a lesson from these online conversations. While many academics have financial and publication constraints that prevent them from attending industry conferences, they can exchange research more actively via blogs, Twitter, and LinkedIn. Our participants stressed that both they and “captive” industry practitioners want to benefit from the results of research. However, Participant 1 mentioned that “academics aren’t that engaged in LinkedIn,” which is a venue that many participants saw as central to organizing and maintaining their professional contacts (i.e., Participant 8 called it a “rolodex”). If academics aren’t present in these spaces, they have no entry in that digital Rolodex. Notably, academics who were mentioned as relevant network ties often already had this kind of online presence. For example, Participant 3 mentioned one specific case:

I pay a good bit of attention to Carlos Evia at Virginia Tech, who’s one of the few people that’s doing more techie stuff on the academic side. So that’s one. All [the relevant field influencers I follow] are all on blogs and have a social media presence and that kind of thing, and certainly they produce valuable information.

Curating digital venues for academic work appears to be one way to participate in conversations accessed by practitioners.

On the other hand, organizers of practitioner-focused conferences might consider some of the financial constraints and realities many academics face. One particular suggestion is to consider tiered pricing for practitioner conferences. For example, in 2016, registering for the STC Summit costs $1,395 (STCb). There is a student price and tiered pricing for members but not for academic colleagues. In fact, the nonmember price is listed at $1,695. The rates for the conference seem to target corporations willing to pay a high cost to send employees to represent a company or to learn. However, the cost for the registration of the STC Summit alone eclipses most annual academic travel budgets. Creating a more cost effective registration rate as a metaphorical olive branch may increase academic engagement in practitioner conferences.

Shared timescales

Several participants mentioned that they did not have time to seek information unless it was to produce a presentation or to help them answer a question that was necessary for completing a contracted project. Participants also stressed a need to have information pushed to them in timely and relevant formats in order to access relevant research. Academics can take a lesson from this need as well by ensuring research is written in clearly accessible language and pushed into channels where it can become findable when it is needed. Research needs to be present not only in the field-shaping pace of books and academic articles but also the “just in time” pace represented by the social media outlets that often support practitioners’ in-the-field or in-the-moment learning exigencies. We believe that publishing academic ideas in accessible and findable spaces can allow for a great deal of creativity in delivery and format. Opportunities certainly exist for writing trade magazine articles based on ideas discovered through research. In addition, publishing study abstracts and article drafts (when granted permission) online and sharing information on platforms such as ResearchGate can help create access to research when it is needed. In some cases, podcasts can be produced and published for practitioner audiences, as well as slideshows and screencasts.

Once again emphasizing the constraints of academic work, practitioners can recognize that the push to make research results available in informal channels comes at an interesting time in the development of academic evaluation procedures. Even with continued perception of academia as “slow-moving,” many academic researchers feel pressure to publish more quickly in response to academic timetables. For example, Blakeslee (2009) suggests that many untenured academic researchers sacrifice projects that they see as interesting or meaningful in order to publish quickly. As one assistant professor in her study put it, “I’ve tended in the past year or two to find more efficient ways of getting research published—rhetorical, textual analyses or quickly accomplished empirical research” (p. 137). Understanding publication pressures surrounding tenure can help create avenues for potential collaboration. Academics are often looking to conduct research in ways that are both high-quality and efficient. Also, academics do research to make a difference. Do not misunderstand, we aren’t suggesting it is the practitioner’s job to collaborate with academics or vice versa. Rather, it is possible that academic and practitioner timescales for doing research could be more aligned than previously thought.

Shared terms and identities

Lastly, TC researchers must carefully consider how to connect to the naming conventions emerging from multiple practitioner subfields (e.g., user experience or information architecture). Of course, conversations about the tensions among field diversity and internal coherence are not new in the field. Academic TC has good reason for developing consistent terms from within its own traditions and discourses; however, academics must illustrate how those terms are related to and intersect with the language emerging from practitioner communities. It appears one reason the apparent divide grows is that academics and practitioners often talk about the field and the work it is doing as separate groups using different terminology.

A lesson both academics and practitioners can take from the participants in this study is to find spaces online to engage with and influence others. In practical terms, this engagement can conjure previously unforeseen connections and ways of thinking, doing, and acting. As well, both academics and practitioners can seek to build spaces to make collaborating on research a practical endeavor that is mutually beneficial. For example, academic research projects that involve practitioner participants can add value through making the research a reflective activity that improves practice. Essentially, the goal for collaborating could be to purposefully bridge existing gaps, much like the participants in this study do to build their reputation as thought-leaders in the field.

In the end, the motivations and activities of most participants in this study were guided by sustaining business goals and financial needs, but their approach to this work offers insight into the accessibility of research across the multidirectional flows of information across TC as a field. Challenges working together on accessing information flows will certainly remain, as academics work to retain rigorous and systematic analyses to test the discourse emerging from practice, and practitioners seek accessible information that helps them get work done, professionalize, and progress in their careers. However, there are some indications that new ways of orienting to TC knowledge are developing, and that the profession’s independent industry leaders are driving these developments. We have long known that a divide between academics and practitioners exists. In fact, we have described how and why the divide functions and exists as it does. What is left is to start doing something about it.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Liza Potts and Bill Hart-Davidson for the conversations we had about practitioner-academic divides, which proved helpful in formulating our ideas. We would also like to thank our participants for supporting the project.

References

Ames, A. L. (2002). Contracting versus consulting: Making an informed, conscious decision. Technical Communication, 49, 154–161.

Andersen, R. (2014). Rhetorical work in the age of content management: Implications for the field of technical communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 28, 115–157.

Barker, T., and Poe, K. (2002). The changing world of the independent: A broader perspective. Technical Communication, 49, 151–153.

Bernhardt, S. A. (2002). Active-practice: Creating productive tension between academia and industry. In B. Mirel & R. Spilka (Eds.), Reshaping technical communication: New directions and challenges for the 21st century (pp. 81–90). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Blakeslee, A. (2009). The technical communication research landscape. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 23, 129–173.

Blythe, S., Lauer, C., and Curran, P. (2014). Professional and technical communication in a web 2.0 world. Technical Communication Quarterly, 23, 265–287.

Broach, W., Gallagher, L. G., & Lockwood, D. (2006). Marketing and advertising for independents. Intercom, 53(3), 12–15.

Burton, P., Wu, Y., Prybutok, V.R., & Harden, G. (2012). Differential effects of the volume and diversity of communication network ties on knowledge workers’ performance. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 55, 239–253.

Carliner, S., Coppola, N., Grady, H., and Hayhoe. G. (2011). What does the transactions publish? What do transactions’ readers want to read? IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 54, 341–359.

Dicks, S. (2002). Cultural impediments to understanding: Are they surmountable? In B. Mirel & R. Spilka (Eds.), Reshaping technical communication: New directions and challenges for the 21st century (pp. 13–25). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Dubini, P., and Aldrich, H. (1991). Personal and extended networks are central to the entrepreneurship process. Journal of Business Venturing, 6, 305–313.

Ferro, T., and Zachry, M. (2014). Technical communication unbound: Knowledge work, social media, and emerging communicative practices. Technical Communication Quarterly, 23, 6–21.

Glick-Smith, J., and Stephenson, C. (1998). Getting professional help: Why contractors and independent consultants need lawyers. Technical Communication, 45, 89–94.

Greve, A., and Salaff, J.W. (2003). Social networks and entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(1), 1–22.

Jack, S., Drakopoulou Dodd, S., & Anderson, A. (2004). Social structure and entrepreneurial networks: The strength of strong ties. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 5(2), 107–120.

Killoran, J.B. (2010). Promoting the business web sites of technical communication companies, consultants, and independent contractors. Technical Communication, 57, 137–160.

Killoran, J.B. (2011). The web portfolios of technical communicators. . .and the documents of their clients. Technical Communication, 58, 217–237.

Killoran, J.B. (2012). Is it “about us”? Self-representation of technical communication consultants, independent contractors, and companies on the web. Technical Communication, 59, 267–285.

Lam, Chris. (2014). Where did we come from and where are we going? Examining authorship characteristics in technical communication research. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 57, 266–285.

Lauren, B., and Pigg, S. (in press). Networking in a field of introverts: The egonets, networking practices, and networking technologies of technical communication entrepreneurs. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59(4). doi: 10.1109/TPC.2016.2614744.

Mirel, B., and Spilka, R. (2002). Introduction. In B. Mirel & R. Spilka (Eds.), Reshaping technical communication: New directions and challenges for the 21st century (pp. 81–90). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Poe, S. D. (2002). Technical communication consulting as a business. Technical Communication, 49, 171–180.

Rainie, L. and Wellman, B. (2012). Networked: The new social operating system. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Read, S., & Swarts, J. (2015). Visualizing and tracing: Research methodologies for the study of networked, sociotechnical activity, otherwise known as knowledge work. Technical Communication Quarterly, 24, 14–44.

Rehling, L. (2004). Reconfiguring the professor-practitioner relationship. In T. Kynell-Hunt and G. Savage, Power and Legitimacy in Tech. Communication, vol. 2. (pp. 87–100). Amityville, NY: Baywood.

Rude, C.D. (2009). Mapping the research questions in technical communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 23, 174–215.

Shriver, K. (2002). Taking our stakeholders seriously: Re-imagining the dissemination of research in information design. In B. Mirel & R. Spilka (Eds.), Reshaping technical communication: New directions and challenges for the 21st century (pp. 111–134). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Scott, J. (2013). Social Network Analysis. Los Angeles, CA and London: Sage.

Sheffield, R. (2009). The web content strategist’s bible: The complete guide to a new and lucrative career for writers of all kinds. Createspace.

Slotte-Kock, S. & Coviello, N (2010). Entrepreneurship research on network processes: A review and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(1), 31–57.

Spinuzzi, C. 2013. Topsight: A guide to studying, diagnosing, and fixing information flow in organizations. Createspace.

STCa. (2004). STC’s U.S. independent contractor/temp agency employee survey. Intercom, 51(3), 14–22.

STCb. (2016). STC Summit Registration Rates. Retrieved from http://summit.stc.org/conference/registration-rates/

STC Consulting and Independent Contracting SIG. (2005). STC Consulting and Independent Contracting SIG survey results. Retrieved from http://www.stcsig.org/cic/pdfs/CICSIGSurveyReport11-05.pdf

Wasserman, S., and Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wellman, B. (1993). An egocentric network tale: Comment on Bien et al. Social Networks, 15, 423–436.

About the Authors

Benjamin Lauren is Assistant Professor of experience architecture (XA) in the Writing, Rhetoric, and American Cultures Department at Michigan State University, where he teaches professional writing, experience architecture, and rhetoric and writing. He is also a Writing, Information, and Digital Experience (WIDE) Researcher and the Book Editor at Communication Design Quarterly (CDQ). Ben also produces a podcast series for CDQ. His research focuses on how people manage creative and collaborative activities in professional contexts. Recent projects have addressed mobile application development, refactoring and systems theory, and project management. He can be reached at blauren@msu.edu.

Stacey Pigg is an Assistant Professor of scientific and technical communication and the Associate Director of Professional Writing at North Carolina State University, where she is a core faculty member in the CRDM Ph.D. Program. Her research has been published in journals such as College Composition and Communication, Rhetoric Society Quarterly, Technical Communication Quarterly, and Written Communication. She teaches courses in rhetorical theory, online information design, and professional communication. She can be reached at slpigg@ncsu.edu.

Manuscript received 1 May 2016; revised 13 June 2016; accepted 14 June 2016.