Abstract

Purpose: Increasingly, technical communicators need to develop materials that meet the usability expectations of audiences in different nations and from different cultures. This article presents a research approach technical communicators can use to better understand and design materials for the different contexts in which individual in other nations use a given technology or communication product.

Method: I review how an understanding of the context in which individuals use an item (i.e., context of use) affects what constitutes usability in a setting. I then review how script theory (from cognitive psychology) and prototype theory (from linguistics) can be combined to create an effective method for identifying the variables affecting use in different cultural contexts.

Results: A focused application of script theory can provide technical communicators with a framework for identifying the variables affecting usability in different cultural contexts. Such identification can be enhanced by a targeted application of prototype theory, and technical communicators can use a combination of script theory and prototype theory to develop communication products more attuned to different cultural contexts of use.

Conclusion: When combined in a focused way, a script-prototype theory approach to researching the context of use in other cultures can help technical communicators better understand such contexts and design materials that better meet the expectations of users in other cultures.

Keywords: usability, user experience design, culture, international communication, localization

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Presents an approach for engaging in context-based user experience design

- Overviews a method for doing effective research on the usability expectations of other cultures

- Provides a mechanism for studying context-based and cultural design expectations associated with usability

Introduction

Today, the interconnected global economy means many businesses regularly engage in some form of international interaction. Success in such contexts is often a matter of usability: Do consumers in different markets find a particular product easy to use—and thus worth purchasing? For this reason, organizations need to begin thinking of usability in terms of different cultural perspectives of use. Specifically, the better an organization understands the expectations of other cultural audiences, the more effectively it can design products and services to meet them.

Culture, however, is nuanced and complex. Knowing what factors to consider when engaging in international user experience design (I-UXD) is thus no small undertaking. Technical communicators, information designers, and user experience (UX) professionals can therefore benefit from applications that help identify aspects affecting usability and design in different cultural contexts. A modified version of script theory (from cognitive psychology), combined with a targeted application of prototype theory (from linguistics), can provide a mechanism for understanding the settings in which cultures use communication products.

This entry explains how the combination of these two theories can help address this situation. The entry begins with an overview of how contextual factors affect expectations of use and how such factors can vary across cultures. Next, I summarize the fundamentals of script theory and prototype theory to reveal how they can help communication professionals identify the variables affecting use/usability in different international contexts. The entry then concludes with a discussion of how this combined script-prototype theory approach can facilitate effective design in international UXD (I-UXD) projects. Through this approach, I reveal how theoretical concepts from other fields can assist with I-UXD processes.

Culture, Context, and Use (Ability)

No technology is culture-free. Rather, items designed by humans generally reflect the cultures that created them (Pacey, 1996; Gautam & Blessing, 2009; Norman, 2012; Sun, 2012; Otto & Smith, 2013). Such factors might be connected to the physical environment/context in which a culture exists (e.g., designing a plow to till the soil found in an area). Technologies can also reflect the beliefs and attitudes the members of a culture associate with tasks performed in a context (e.g., designing a plow to reflect cultural attitudes toward farming according to custom or religious belief). As such, products designed for use in the context of one culture can be ill-equipped to operate as effectively in the context of another (Pacey, 1996; Yunker, 2003; Sun, 2012).

Such factors are central to localization: The idea is that items designed for one culture need to be revised to meet the preferences and expectations of another (Yunker, 2003; Esselink, 2000). Financially, there is the temptation to restrict such “cultural re-tooling” to a limited surface level. In such cases, a product is initially designed to meet the expectations of one culture (the culture that created it), and individuals then revise that original item to address the expectations of other cultures. The changes needed to address cultural expectations effectively, however, are often deeper than the relatively “superficial” revisions some associate with localization practices (e.g., changing images to meet cultural preferences) (Sun, 2012). In truth, a re-design of the product is often essential to meeting the needs of users in global contexts.

In certain instances, an organization might decide it is not enough to revise an existing product for international audiences. Rather, the organization needs to develop a new version of the product for audiences in other cultures. (Ideally, organizations would create a culture-specific version for each of the cultures with which these materials are shared.) The idea is that each of these culture-specific, parallel products better meets the preferences and needs of different cultural groups. In such processes, a product is not initially designed for one culture and then revised to meet the expectations of others. Rather, multiple versions of the same product are created with each version designed to meet the contextual expectations a given culture associates with the use of that item. This process is sometimes referred to as transcreation or glocalization, for one is redesigning an overall product across cultural lines (Bauman, 1998; Thompson & Arsel, 2004; Sun, 2012; Merino, 2006; Pedersen, 2014; Munday, 2016). These processes generally involve developing new content to convey a common theme or achieve a common objective across different cultures vs. re-working existing content for international audiences. As such, transcreation and glocalization can also entail using different methods and modes for conveying the same idea to different cultural groups (Welocalize, 2016; Lionbridge, 2016; casestudyinc, 2014).

These approaches are all connected to a central concept: One needs to know the contexts in which individuals use an item to design materials that meet the dynamics of that context (Petroski, 1992; Otto & Smith, 2013). This factor means the design of objects does not inherently fit with a context of use. Rather, designers need to develop materials to conform to the conditions (i.e., makes them usable) of a given context of use (Spinuzzi, 2000; Potts & Bartocci, 2009; Nielson Norman Group, 2014; Mara & Mara, 2015). As such, the old design adage “form follows function” no longer applies. Form must instead address the context in which individuals perform a function. Thus, the approach needs to be “creation conforms to context.” Unfortunately, this perspective brings new challenges for communication professionals.

The Complexities of the Context of Use

The connection between context and usability is not new. In truth, it is a cornerstone of user experience design (UXD) (Garrett, 2010; Hassenzahl & Tractinsky, 2006; Buchenau & Suri, 2000). After all, technical communicators need to understand the experiences of the individual user in order to determine how to design an item to best meet the parameters of this context of use (Getto & St.Amant, 2014). Yet, this approach complicates the design process, for it means individuals can no longer rely exclusively on laboratory-style testing to identify variables that affect how individuals use items. Rather, the designer needs to understand the actual setting/context in which an item is used.

To this end, communication professionals can employ different approaches to understand contexts of use. In some cases, they might rely on ethnographic observations to determine how individuals use an item in greater society (Spinuzzi, 2000; Mara & Mara, 2015). In others, the designer might turn to surveys or focus groups to answer specific questions on the contexts in which persons make use of an item (e.g., When do you use X? What factors affect that use? etc.) (Grey, 2014). And in still other instances, data collected via different methods can be merged to create an architype, or persona, that reflects the contextual dynamics in which certain individuals use an item (Getto & St.Amant, 2014). Such personas can then serve as a guide for addressing the expectations of different kinds of users (Getto & St.Amant, 2014).

Central to these approaches is understanding contexts of use—the environments in which individuals employ an item. Doing so is not easy, for a number of variables can affect how individuals use materials in a particular setting (Petroski, 1992; Norman, 2012; Rau, Plocher, & Choong, 2013; Berry, Poortinga, Segall, & Dasen, 2002). Moreover, these variables of use are often interconnected: That is, each has the power to affect/change the other variables in that context (Petroski, 1992). For example, how one uses a tool in a given context is often a matter of what objective one wishes to achieve in that setting and what other tools are present in that environment (e.g., using an axe as a wedge or a hammer depending on if a hammer or a wedge is present in and needed in that context) (Petroski, 1992). Within such a complex framework, the question becomes: How does one identify the variables of use at work in a particular context of use?

Pinpointing such variables in one’s native culture can be challenging. Doing so involves a solid understanding of that context in order to:

- Know what objective one wishes to achieve in a given context of use

- Identify the items present in a given context of use

- Determine which items are affecting use (or affecting other variables of use) in that context

- Establish how a variable of use affects the ways individuals employ an item in that context

To effectively address such factors and create usable materials, individuals need to know:

- What variables to look for

- What such variables should look like

- How such variables might affect use

- How to design to address such factors effectively

Thus, understanding the context of use in one’s native culture is a complex process. When attempting to understand the context of use of another culture, this process is further complicated by a range of other factors.

Culture and the Context of Use

The context in which individuals use an item can vary from culture to culture, and such differences have important implications for design. Consider desktop computers and the context of use of an office setting. For individuals in industrialized nations, the mention of this context brings to mind a particular environment that is climate controlled (to some degree) and relatively clean/free of dust and debris. Desktop computers created in these cultures are thus often designed to be usable according to the variables in this context (van Reijswoud & de Jager, 2011). The problem is this same context (the office) can involve different variables and conditions in other nations and regions. Such factors, in turn, affect the usability of the design of an object in these other contexts.

As van Reijswoud and de Jager (2011) note, one major problem with hardware (e.g., desktop computers) developed in industrialized nations is the design of the technology often makes it difficult to use in other settings. In many emerging economies, for example, offices might not be climate controlled. As a result, the prospects of computing equipment overheating and not being operational (i.e., usable) in such contexts constitute real problems. To address this variable of temperature in these settings, individuals must often adapt the design of the technology to make the item usable in that environment (e.g., removing the casing enclosing the hard drive to allow for more air flow around the computer’s circuit boards, CPU, etc.). Add the variable of high levels of sand particulates in the air (e.g., in a desert context), and individuals again need to adapt the design for the technology to keep it operational and usable in this cultural context of use. (Dusty environments often result in the clogging of cooling fans and other mechanical parts found on many desktops designed for use in industrialized nations.)

The idea that different factors affect the context of use in other cultures is not new. In fact, parallel contexts often have different variables across cultures. For these reasons, scholars such as Getto and St.Amant (2014), Breuch (2015), and Verhulsdonck (2015) have noted that conventional UX and UXD approaches to understating contexts of use (e.g., the use of personas) must be modified to address a range of cultural, geographic, and other variables. Additionally, one problem inherent to understanding other cultural contexts is individuals are often trained to look for items/variables that exist in their own culture and in terms of what that item looks like in that culture (St.Amant, 2015 & 2016; Kostelnick, 1995, 2011). As a result, it might be difficult for a technical communicator from one culture to identify or understand the variables of use at work in the context of use in a different culture. The result is an incomplete understanding of a given context of use related to international settings.

The challenge for technical communicators becomes finding methods, frameworks, or approaches that can help identify the variables of use at work in the contexts of use in other cultures. Such models, moreover, need to help the technical communicator know what variables to look for and what such variables should look like in order to understand such contexts. Fortunately, a modified version of script theory, in combination with a targeted application of prototype theory, can provide a mechanism for addressing such factors.

Script Theory: Identifying Variables in the Contexts of Use

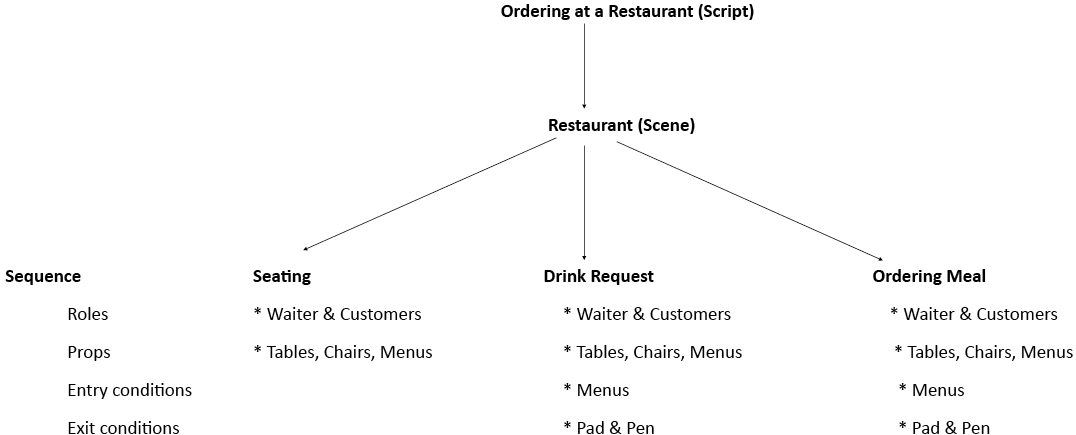

First proposed by Silvan Tomkins in the 1950s, script theory examines patterns of action in particular contexts (Tomkins, 1978, 1987; Norman, 2002). The idea is to identify the variables affecting behavior in an environment so one can understand the assumptions individuals have about what will take place in that setting. To do so, Tomkins borrowed from the language of the theater and viewed discrete units of action in terms of scenes. Each scene was a specific kind of event with a recognizable beginning and ending point (e.g., the process of ordering a meal at a restaurant). Each scene also contained items (variables) that affected the course of actions in a scene (e.g., needing menus to know what to order and a waiter to take the order). Individuals then planned their behavior in a context based upon what they expected to take place in that scene/context. Accordingly, the more technical communicators understand scene-related experiences, the better they can design materials to meet the user’s expectations of what will take place in that context. (Knowing, for example, one needs a menu to order in a restaurant allows one to account for the design of other items to facilitate the ordering process.)

To better understand this context for action, Schank and Abelson (1977) extended Tomkins’ ideas and identified other script-based variables that affected expectations and behaviors in a scene. These items included:

- Scene: The process of performing a particular standard activity/action (e.g., ordering at a restaurant)

- Setting: The location/context in which the action (scene) takes place (e.g., the restaurant)

- Roles: The individuals one expects to encounter in and play a specific role in a given setting (e.g., waiter and customers)

- Props: The items one expects to encounter and to use—or that others will have and use—in a scene to achieve the objective of the overall scene (e.g., tables, chairs, menus)

- Entry Conditions: The criteria something must meet to enter a scene/how items get into a scene (e.g., menus carried to a table by a waiter when customers are seated)

- Exit Conditions: The criteria something must meet to exit a scene/how items leave the scene (e.g., menus carried away by a waiter after customers have ordered) (Schank & Abelson, 1977)

As well as:

- Sequence: The order in which events/individual actions happen in a scene (e.g., customers enter the restaurant, customers are seated by hostess/host, waiter takes customers’ orders) (Schank, 1973; Abelson, 1973)

Each factor represents something individuals look for when performing an activity in a particular context. As such, the presence or absence of script-based items influences a person’s expectations of usability in a setting (Norman, 2002). If, for example, the expected items are there, then one can use them to perform a task as desired and expected in that context. If not, one cannot. In this way, these script-based items provide technical communicators with a framework for tracking the factors, or variables, individuals associate with usability in specific settings.

These expectations, moreover, are based on experience over time (Shiraev & Levy, 2004). That is, by repeatedly performing an activity in a given context (e.g., ordering at a restaurant), the individual develops a script for what should take place in that context. This factor means the script-related expectations of one individual do not inherently map onto those of another. The greater the differences among the experiences of individuals, the more divergent the scripts. For this reason, technical communicators cannot simply use the scripts of their native culture to guide design in international environments. Rather, they need to understand the script-based expectations of other cultures to develop materials international audiences will view as usable in a particular setting.

To apply script theory to I-UXD, individuals should first ask (and address) the following questions:

- What is the overall objective the user wishes to accomplish (scene)?

- In what context will the user perform the actions needed to achieve this objective (setting)?

- What are the various, individual steps the user must take—and in what order—to achieve this objective in this context (sequence)?

- What individuals will the user expect to rely on to perform these tasks in this context (roles)?

- What items does the user expect to employ (or for others to use) to perform the essential tasks in this process (props)?

- How can the user access or obtain materials and information at different points in the process (entry conditions)?

- How can the user remove items from or send/transmit information during the process (exit conditions)?

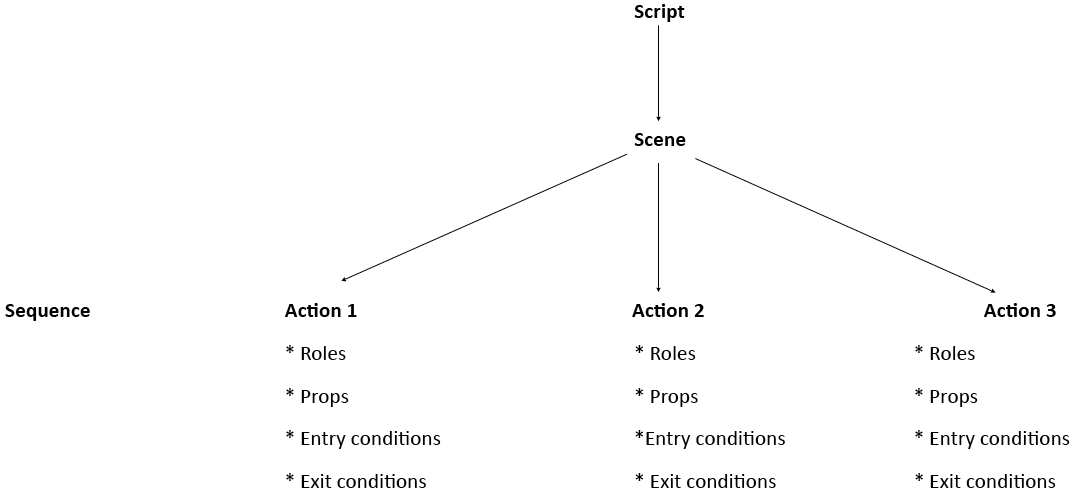

The resulting answers can help technical communicators identify what constitutes usability for individuals from other cultures. Researchers can next map these answers into frameworks or models akin to the examples in Figure 1a and 1b. Technical communicators could then use this map to guide their design activities according to the script expectations of users from other cultures.

Technical communicators could also employ a variety of methods to identify the script-based expectations other cultures associate with a particular context of use. These approaches include:

- User Interviews: Interview users from the other culture and ask them to identify the script-related variables noted here. (For the process of calling an online help system, ask individuals “What do you expect to encounter during this process?” Also ask about the sequence of actions: “What is the sequence of events during this process?” and “Who is present/participates in the process to help you?”)

- Focus Groups: Meet with groups of individuals from the intended audience and request participants to explain the process of completing a particular task in a given context. In so doing, the technical communicator could ask group members to respond to specific script-based questions as they move through the process (e.g., “For the process of accessing customer support online, what is the first thing you do? What do you expect to see on that screen? How are you obtaining the information needed to perform this particular task?”)

Once a technical communicator has developed a draft script from this initial research, she or he should have members of the related culture review and comment on that script to note if:

- Any essential script-related element is mis-identified or missing from this context of use

- Something the observer identified as a variable of use actually does affect behavior in that context

While script theory can help identify variables influencing usability in a context, one problem remains: identification. That is, what a variable should look like in a given context can vary from culture to culture and in unexpected ways. This factor means it might be difficult for technical communicators from one culture to identify script-based variables of use in another.

The Representation Problem: The Appearance of Variables in the Context of Use

What a particular item/variable of use (e.g., a prop or a role) should look like in a given context can vary from culture to culture (Kostelnick, 2011; Kostelnick & Roberts, 1998). In some cases, these differences affect recognition: The individual is unable to recognize the item she or he is looking for because the design of that item is so different in another culture (St.Amant, 2005; Kostelnick & Roberts, 1998). Lack of recognition thus results in lack of use. In other cases, such cultural variations don’t inhibit recognition, but they do affect acceptability. In these cases, the design of the item might make the object recognizable, but the way in which the item is depicted is considered unacceptable (or offensive) (St.Amant, 2005; Aitchinson, 1994). As such, the unacceptable item is not used.

These factors have important implications for I-UXD. Consider the use of a gesturing hand to point users to a particular menu option. The finger(s) one should use for legitimate pointing motions vs. making an obscene gesture are set by cultural expectations (Horton, 1994). Such expectations, moreover, can vary from culture to culture. (Certain representations of the US hand gesture of “V for victory” are an obscene gesture in the UK; others are not.) In such situations, script-based analysis of context might identify a hand with a pointing finger as a prop individuals in a culture associated with the effective design of an interface. If, however the designer is not careful, she or he might produce an interface that contains an obscene gesture (vs. an expected prop) that affects the use of that item. Thus, technical communicators need to be aware of cultural expectations of recognizability and acceptability when developing materials for different contexts of use.

These recognition and acceptability factors have pronounced implications for researching contexts of use. To track variables of use in a given context, technical communicators must be able to identify those variables and determine their appropriateness. Technical communicators therefore need to know what these variables look like in that context. Cultural differences, however, might mean technical communicators are unable to identify certain variables in the context of use of another culture (St.Amant, 2016).

But the identification of variables is not the only problem. Once identified, the technical communicator must replicate these variables when designing materials other cultures consider usable. To address this situation, technical communicators need a mechanism that can augment script theory and identify the variables of use in various cultural contexts. Such a mechanism must also account for expectations of recognizability and acceptability based on cultural norms. Prototype theory can serve as such a mechanism.

Prototype Theory: Identifying Variables of Use in Different Cultural Contexts

Proposed by Eleanor Rosch in the 1970s and more recently used in technical communication, prototype theory examines the connections between words and visuals (Rosch, 1978; St.Amant, 2005). The idea works as follows: For most words in a language, individuals have a visual representation of what that item should look like. So, when an individual hears a word like hammer, a particular image of a hammer springs to mind. This visual represents the ideal of the prototype for what something should look like for the individual to identify it as a hammer (Rosch, 1978; Aitchison, 1994). When the individual encounters a new object, she or he compares that new object to all of the ideals (visual representations) in his or her mental database. If the new object looks very much like the individual’s ideal for a given item, then the individual will identify it as such. If not, the individual will move on to compare the new object to other ideals until a more exact match is found (Aitchison, 1994; St.Amant, 2005).

This comparative identification process is not based on the overall depiction of an item but on the different characteristics (i.e., parts) that collectively comprise an ideal. When one compares a new object to a particular ideal, that individual does not look at that ideal as a single, self-contained unit. Rather, the individual views that ideal as a collection of design features. She or he then attempts to determine how many of those individual features—or characteristics—the new item has in common with the ideal to which it is being compared (Aitchison, 1994; St.Amant, 2005). The more characteristics the new item has in common with an ideal, the more likely that new item is to be identified as such. (For example, the more characteristics a new item has in common with one’s ideal for hammer, the more likely the individual is to identify that object as a hammer.)

Where do these ideals and their related visual characteristics come from? Like scripts, individuals learn these prototype expectations based on exposure over time. That is, the more an individual experiences a particular visual used in association with a given concept (e.g., always sees the same object when persons around them use the word hammer), the stronger the association becomes between the appearance of that item and what the ideal for the related object should look like (Aitchison, 1994). It is through such repeated exposure over time that individuals form their prototype-ideal expectations. As cultures often expose individuals to different items in relation to the same term or concept, the idea an individual uses to recognize items in one culture might differ from another (Kostelnick, 1995; St.Amant, 2005).

Similarly, one’s native culture also teaches him or her what an acceptable (vs. just a recognizable) depiction of a given item should look like (e.g., what constitutes a recognizable vs. an acceptable depiction of a teacher based on how the individual is dressed) (St.Amant, 2015). These factors mean technical communicators cannot assume what something looks like is universal in terms of recognizability and acceptability (St.Amant, 2015). Rather, the individual needs to know:

- What the ideal for the related item is in a given culture

- What features/characteristics members of that culture associate with recognizable and acceptable depictions of an item

This information is key to identifying items in the contexts of use of other cultures.

How, then, can technical communicators effectively identify the prototypes (and related characteristics) that individuals from other cultures associate with variables of use in a given context? By doing the following things:

- Conduct interviews in which individuals from a culture are asked to describe what items (props) or individuals (roles) should look like/what features they should have to be recognizable and acceptable in a particular setting (e.g., What does a doctor look like in the setting of an emergency room?).

- Ask interviewees to draw an example of what a given item or individual should look like in a given context of use (e.g., What does an ATM look like in your culture?). As they do so, ask the interviewees to identify the key features/characteristics they are including to make the image recognizable and acceptable to other members of their culture (e.g., Which features are particularly important for you to identify this object as a file storage unit?).

- Ask interviewees to comment on different depictions of an item or individual in terms of how recognizable and acceptable that depiction is (e.g., Is this image an effective representation of a workstation?). Also ask what the interviewee would do (what features she or he would add, modify, or remove) to make that depiction more recognizable and acceptable to members of his or her native culture (e.g., How would you improve this image of a workstation?).

Technical communicators can obtain such information via individual interviews or discussions with small groups/focus groups comprised of individuals from the related culture. Technical communicators could also combine these approaches (e.g., use interviews to gain initial information, then create draft images that are critiqued by members of a focus group). The core idea is for individuals from the related culture to provide design/prototype information on the context of use in that culture. Technical communicators can use this information to identify variables in a context of use and to design materials for that context.

Putting It All Together: The Overall Script-Prototype Approach to I-UXD

Script theory and prototype theory each offer a mechanism for understanding the expectations of different cultural audiences. When combined, this script-prototype approach can be a powerful tool for researching the contexts of use in different cultures. The key to success involves merging these two frameworks into a process technical communicators can employ when researching the variables affecting use in different cultural contexts.

The starting focus: Identifying the context/scene

The first step in this process involves identifying the context of use one wishes to study. Once the context is known, the technical communicator can map the related script and identify the variables of use at work in this context. (See Figure 1a and 1b for an example of such mapping.) The central question to ask here is, “In what context do individuals from this culture engage in process X?” (e.g., “In what context to university students in Japan use mobile phones to access online help systems?”). The answer is important, because individuals from different cultures can engage in the same process in a variety of contexts. Many Anglo-Americans, for example, check work email all the time from any location they can obtain online access. Many Danes, by contrast, only check work email from the workplace/office during work hours. Each of these contexts of use involves different variables the technical communicator needs to identify to map an effective script of use for the related cultural audience. Each of these contexts of use also represents a foundational script for context of use in that culture.

Answers to this initial question can come from short interviews or brief questionnaires that ask individuals from a particular cultural audience, “Where and when do you do X?” (e.g., “Where and when do you check you work email?”). The related responses identify the setting/scene the technical communicator will need to map to identify the variables of use at work in a given environment.

The sequence of actions: Tracing the process of events in the scene

Once the overall scene is known, the next step becomes identifying:

- The actions one needs to perform to achieve the overall objective of this scene

- The sequence in which such actions must occur to achieve that objective

Mapping these factors can involve interviews or focus groups in which individuals are asked, “Talk through/explain the different steps or actions you will take to perform this overall task in this setting.” At this point, compiling the results obtained from multiple sources is important, because individuals might use different actions to achieve the overall objective in a context of use. The key is for technical communicators to identify an overall, general sequence of events based on the frequency in which an action is performed in the context of use in a given culture.

To map such settings, the technical communicator could use initial interviews with members of the related culture and record the sequence of events related by each interviewee. The technical communicator could then compare these results and create a map of an initial sequence of tasks/activities for that context of use in that culture. The technical communicator could next share this initial map with a focus group comprised of members from that culture. Participants in this group could provide the information and insights needed to modify that draft map of tasks/activities into one that better reflects the general expectations many members of the related culture associate with that context of use.

Mapping the variables of use: Applying prototypes to scripts

Once the scene is identified and the sequence of events is mapped, the next step becomes cataloging the variables of use in that context. Doing so involves two parts: Collecting focused responses and performing participant observations.

Collecting focused responses involves obtaining information directly from the members of a culture. Ideally, technical communicators can do this through interviews in which they employ a series of questions to identify the variables members of a culture associate with the actions/tasks that occur in a particular context of use (e.g., using one’s mobile phone to access an online help system). Such a process would start with an open-ended directive like, “Tell me how you would do X.” As the interviewee talks through the process, the technical communicator could ask more focused questions to determine what variables were involved with different parts of this process. Such questions might be:

- What items are in the area around you? (to identify potential props)

- Do you use any of them for this process? (to identify actual props)

- Would anyone be available to help with this process? (to identify roles)

- How would you contact/speak with that person and when? (to identify entry conditions)

- How would you know you had the correct person? (to identify roles)

- What do you expect that person to do or say? (to identify roles)

Through such guided questioning, the technical communicator can obtain data on the variables of use expected in the related context.

During this process, the technical communicator also needs to obtain prototype data on what the variables in the overall scene should look like. Technical communicators should therefore ask interviewees to identify and describe the variables in a given scene. In such a process, the technical communicator should first ask the interviewee to identify the variables present (e.g., What are you using to do task X?). Once the variable is identified, the technical communicator should ask the interviewee to describe the appearance of that variable (e.g., Can you describe X to me? What does it look like?). Such a process might work as follows:

- For props: “Can you tell me what objects are in the environment around you? Which objects would you use to perform task X of a process? Can you describe those objects to me? What do they look like so you know what they are? How will you use them?”

- For roles/actors: “Who else is in this environment? How do you know who they are/what features identify who they are? How will they assist you with different tasks in this process? What will they do or say to help with this task?”

Such guided, open questioning helps technical communicators identify:

- The different variables at work in the script for a given context of use

- The prototypes (and characteristics) associated with identifying those variables in that context

Technical communicators can use this information to map different contexts of use and create materials that meet related user expectations for that environment.

Observational research: Testing one’s findings

Once technical communicators have identified the different script factors/variables and their related prototypes, they need to test such factors. This is because interview data is not necessarily representative of reality. In truth, individuals can mis-remember or embellish certain details (Zimmerman & Muraski, 1995). Technical communicators therefore need to review the sequence of events and the variables of use identified in a given context to determine if:

- Events in a sequence are present and occur as described (sequence)

- Variables of use identified by research are actually present (props and roles)

- Variables of use actually look like the items described by interviewees (prototypes)

- Individuals (and roles) employ these variables of use as described by interviewees

Confirming such factors involves a different kind of research: ethnographic observation.

For this part of the process, the technical communicator would situate her- or himself in a given context of use of another culture and either ask the participant to undertake a given process or watch as members of that culture engage in that process (Spinuzzi, 2000; Otto & Smith, 2013). During this observational period, the technical communicator would look for certain script-related items:

- Is the process/sequence of actions taking place as identified?

- Are the variables identified through the initial research used as described by interviewees and focus group participants?

- Are those variables being employed in the same way as identified in the initial research?

The technical communicator also needs to scrutinize the script-related elements in that environment to confirm prototype-related findings (i.e., if variables have the characteristics the interviewees claim they should). Technical communicators can use the results of such observational research to modify the initial script-prototype framework for usability in this context and to test it again to see how closely this modified script (and related prototypes) conforms to follow-up observations.

While essential, this observational confirmation needs to come at the end (vs. the start) of this research process. The reason is recognition: Until individuals know what items to look for in the context of use of another culture, the results of observational research could be inaccurate or skewed. This problem is due to the fact that individuals tend to look for what their native culture tells them should be in a given context of use (St.Amant, 2016). Moreover, even if the observer can identify variables not found in her/his native culture, she or he might try to understand those variables according to the parameters of her/his native culture (i.e., just because I can see X does not mean I know why X is there or what it does in that context) (St.Amant, 2016). For this reason, such observational research should occur after individuals know what to look for and why.

Prospective next steps in the process

The results of this script-prototype research process allow technical communicators to do a number of things. First, they can create personas of kinds of users from other cultures and use these personas to guide the design process (Getto & St.Amant, 2014). Second, they can use this information to create and test initial designs of a product with a given cultural audience and modify that design based on feedback. Third, they can engage in field research to study how individuals in a culture attempt to achieve certain objectives in a particular context. Finally, they can use such results to revise existing materials or decide to develop completely new ones based on the contextual expectations of users from other cultures. In these ways, the script-prototype approach to I-UXD can provide technical communicators with a mechanism for exploring a range of usability-related aspects in different international settings.

Conclusion

As the economies of the world become increasingly intertwined, technical communicators will need to know how to design materials for a range of international audiences. Success will be a matter of usability—creating products and services that are easy to use in a range of cultural environments. Achieving this objective will require technical communicators to approach user experience design according to the contexts of use found in different cultures. To do so, technical communicators need to employ methods that can help them identify, understand, and address the variables affecting use in such contexts. The combined script-prototype approach described here can serve as an important mechanism for achieving this objective.

Viewing usability from a script theory perspective helps technical communicators know what variables to look for in a given context of use. The combined use of prototype theory with script theory can further help technical communicators identify those variables. The key is to employ this approach in a way that gleans effective, initial data on users from other cultures and then to develop and test designs based on these findings. By comparing the results of script-prototype research on context of use in other cultures, academic researchers and industry practitioners alike can gain a better, more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics affecting usability in other cultures.

References

Abelson, R. P. (1973). The structure of belief systems. In R.C. Schank & K.M. Colby (Eds.), Computer models of thought and language (pp. 287–339). San Francisco, CA: Freeman.

Aitchison, J. (1994). Bad birds and better birds: Prototype theory. In V. P. Clark, P. A. Eschholz, & A. F. Rosa (Eds.), Language: Introductory Readings 4th ed. (pp. 445–459). New York: St.Martins.

Bauman, Z. (1998). On glocalization: Or globalization for some, localization for others. Thesis Eleven, 54(1), 37–49.

Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Segall, M. H., & Dasen, P. R. (2002). Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge UP.

Breuch, L. A. K. (2015). Glocalization in website writing: The case of MNsure and imagined/actual audiences. Computers and Composition, 38, 113–125.

Buchenau, M. & Suri, J. F. (2000). Experience prototyping. DIS ’00 Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques (424–433). New York: ACM. casestuidyinc.com. (2014). Glocalization examples—Think globally and act locally. Retrieved from http://www.casestudyinc.com/glocalization-examples-think-globally-and-act-locally

Esselink, B. (2000). A practical guide to localization. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Garrett, J. J. (2010). The elements of user experience: User-centered design for the web and beyond 2nd ed. Indianapolis, IN: New Riders.

Gautam, V. & Blessing, L. (2009). Cultural influences on the design process: An empirical study. Proceedings of the ICED 09, 17th International Conference on Engineering Design, Vol. 9 (pp. 115–122). Palo Alto, CA: Human Behavior in Design.

Getto, G. & St.Amant, K. (2014). Designing globally, working locally: Using personas to develop online communication products for international users. Communication Design Quarterly, 3(1), 24–46.

Grey, C. (2014). Better user research through surveys. UX Mastery. Retrieved from http://uxmastery.com/better-user-research-through-surveys/

Hassenzahl, M. & Tractinsky, N. (2006). User experience—A research agenda. Behaviour & Information Technology, 25(2), 91–97.

Horton, W. (1994). The icon book: Visual symbols for computer systems and documentation. New York: Wiley.

Kostelnick, C. (2011). Seeing difference: Teaching intercultural communication through visual rhetoric. In B. Thatcher & K. St.Amant (Eds.), Teaching intercultural rhetoric and technical communication (pp. 31–48). Amityville, NY: Baywood Publishing Company.

Kostelnick, C. & Roberts, D. D. (1998). Designing visual language: Strategies for professional communicators. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Kostelnick, C. (1995). Cultural adaptation and information design: Two contrasting views. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 38, 182–196.

Lionbridge. (2016). Transcreation services: Take your creative marketing content global. Retrieved from http://www.lionbridge.com/solutions/transcreation/

Mara, A. & Mara, M. (2015). Capturing social value in UX projects. SIGDOC ’15: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual International Conference on the Design of Communication. New York: ACM.

Merino, M. B. (2006). On the translation of video games. The Journal of Specialized Translation. Retrieved from http://www.jostrans.org/issue06/art_bernal.php

Munday, J. (2016). Introducing translation studies: Theories and applications 4th ed. New York: Routledge.

Nielsen Norman Group. (2014). Context-specific design in the cross-channel user experience. Retrieved from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/context-specific-cross-channel/

Norman, D. (2012). Does culture matter for product design? Core 77. Retrieved from http://www.core77.com/posts/21455/Does-Culture-Matter-for-Product-Design

Norman, D. (2002). The design of everyday things. New York: Basic Books.

Otto, T. & Smith, R. C. (2013). Design anthropology: A distinct style of knowing. In W. Gunn, T. Otto, & R. C. Smith (Eds.), Design anthropology: Theory and practice (pp. 1–29). New York: Bloomsbury.

Pacey, A. (1996). The culture of technology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Pedersen, J. (2014). Exploring the concept of transcreation: Transcreation as ‘more than translation’? Cultus: The Journal of Intercultural Mediation and Communication, 7, 57–70.

Petroski H. (1992). The evolution of useful things: How everyday artifacts—from forks and pins to paper clips and zippers—came to be as they are. New York: Knopff.

Potts, L. & Bartocci, <Method>Experience Design </Methods>. Proceedings of the 27th ACM International conference on Design of Communication (17–22). New York: ACM.

Rau, P. L. P., Plotcher, T, & Choong, Y. Y. (2013). Cross-cultural design for IT products and services. New York: CRC Press.

Rosch, E. (1978). Principles of categorization. In E. Rosch & B. B. Lloyd (Eds.), Cognition and Categorization (pp. 27–48). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

St.Amant, K. (2016, February). The five principles of research in culture, communication, and design. Intercom, 63(2),17–20.

St.Amant, K. (2015). Culture and the contextualization of care: A prototype-based approach to developing health and medical visuals for international audiences. Communication Design Quarterly, 3(2), 38–47.

Schank, R. C., & Abelson, R. P. (1977). Scripts, plans, goals, and understanding. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schank, R. (1973). Causality and reasoning. Technical Report #1. Istituto per g l i studi Semantic1 e Cognitivi. Castagnola, Switzerland.

Shiraev, E. & Levy, D. (2004). Cross-cultural psychology: Critical thinking and contemporary applications 2nd ed. Boston: Pearson.

Spinuzzi, C. (2000). Investigating the technology-work relationship: A critical comparison of three qualitative field methods, in Proceedings of the IEEE Professional Communication society Professional Communication Conference and Proceedings and Proceedings of the 18th Annual ACM International Conference Computer Documentation: Technology & Teamwork, 24–27, Cambridge, MA.

Sun, H. (2012). Cross-cultural technology design: Creating culture-sensitive technology for local users. New York: Oxford UP.

Thompson, C. & Arsel, Z. (2004). The Starbucks brandscape and consumers’ (anticorporate) experiences of glocalization. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(3), 631–642.

Tomkins, S. S. (1987). Script theory. In J. Arnoff, A. I. Rabin, & R.A. Zucker (Eds.), The emergence of personality (pp. 147-216). New York: Springer.

Tomkins, S. S. (1978). Script theory: Differential magnification of affects. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 26, 201–236.

van Reijswoud, V. & de Jager, A. (2011). The role of appropriate ICT in bridging the digital divide: Theoretical considerations and illustrating cases. In K. St.Amant & B. A. Olaniran (Eds.), Globalization and the digital divide (pp. 59–88). Amherst, NY: Cambria Press.

Verhulsdonck, G. (2015). From cultural markers to global mobile: Using interaction design for composing mobile designs in global contexts. Computers and Composition, 38, 140–150

Welocalize.com. (2016). Three differences between transcreation and translation. Retrieved from https://www.welocalize.com/three-differences-between-transcreation-and-translation/

Yunker, J. (2003). Beyond borders: Web globalization strategies. Indianapolis, IN: New Riders.

Zimmerman, D. E. & Muraski, M. L. (1995). The elements of information gathering: A guide for technical communicators, scientists, and engineers. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press.

About the Author

Kirk St.Amant is a Professor and the Eunice C. Williamson Endowed Chair of Technical Communication at Louisiana Tech University (USA). He is also an Adjunct Professor of International Health and Medical Communication with the University of Limerick (Ireland). His research focuses on international and intercultural aspects of health and medical communication and of online media—particularly international virtual workplaces, international outsourcing/offshoring, and the effects of globalization on online education. He can be reached at kirk.stamant@gmail.com.

Manuscript received 15 September 2016, revised 15 November 2016; accepted 23 November 2016.