By Rhonda Stanton, Missouri State University

Abstract

Purpose: This small-scale study investigates the skills and experiences most sought-after by recruiters and hiring managers in entry-level technical writers in the work place. The purpose is to learn whether academic programs offer the course work and opportunities students need. Additionally, I discuss job-ad requirements for entry-level technical writers in the workplace and compare technical/professional academic program offerings with those job-ad requirements.

Method: Recruiters and hiring managers were surveyed to learn their top priorities for skills and experiences. Data from job ads of three job boards was gathered and analyzed, and this data was compared to academic program requirements across the United States.

Results: While technical and professional writing programs are ever-changing and substantially different, there are similarities, and the programs seem to be preparing students well for the workplace.

Conclusion: Most programs require core courses that are similar in name and description and require additional study in an area of expertise or a minor. These core curricula align well to the requirements in entry-level job ads in the industry. More research is needed to learn the best ways students learn in university courses. Additionally, we need to investigate the consistency of internship requirements among programs and encourage industries to consider internship experience as legitimate industry experience.

Keywords: Program Curricula, Job Ad Requirements, Entry-Level Technical Writers, Technical Writing Skills

Practitioners’ Takeaway

- A practitioner looking for a job should recognize that not all job boards are the same.

- Many technical writing programs offer course work and workplace experiences (through internships) that can prepare new graduates well for their first job.

- Employers should recognize that not all internships have the same hour or task requirements but, in many cases, can be accepted as authentic workplace experience.

Introduction

Understanding what skills and experiences managers want in new technical writing employees is important to faculty and program directors of technical/professional writing programs. This should also be a consideration in curriculum design and development. It is equally important that program directors and faculty continually assess the effectiveness of their technical/professional writing (TPW) program requirements. One way to do this is to compare how the requirements of the program translate to the job market for new technical writing employees. While in college, students are able to gain a breadth of knowledge from a foundational and well-formatted general education program, and they can gain a depth of knowledge and special job-specific skills from the major or emphasis in technical/professional writing. While preparing students to be valuable and prepared employees is only one purpose of their educational experience, giving them a strong advantage as they transition into the workplace is an important consideration to administrators.

Program directors and faculty have been asking some of the same questions for years: Should we be teaching specific software tools or just providing a brief overview of some of the functionality with a few? Do we teach specific methodologies for project management or software development? Or do we give an overview of what several are? Should we require literature courses as part of the academic requirements for a degree in technical writing? Should we have an entire class over ethics, or should we intersperse ethics into every class we teach? Program directors must keep these and other questions at the forefront of their minds as they make sure they offer opportunities for students to become well prepared to enter the workplace.

In this article, I report the findings from a survey I conducted and analyzed where I asked recruiters and hiring managers what top three skills they looked for in an entry-level technical writer. I also conducted a small-scale study where I investigated how program requirements translate into job skills. I looked at job requirements in job ads posted on three job boards that may be used by recruiters in the workplace and by students who are ready to graduate and are looking for their first job. I also examined course offerings and degree requirements of technical communication programs in the United States. My two related research questions are the following: What skills, exactly, should new technical communication graduates possess in order to land their first job? Does the world of academia in technical communication prepare students to be valuable and effective technical communicators in the workplace?

Research Methods

The research for this study was three-pronged:

- I collected and analyzed survey responses from recruiters and hiring managers who post job openings, interview candidates, and hire entry-level technical writers to learn their opinions about what skills and experiences are essential for potential candidates who have applied for a job.

- I expanded the literature in Lanier’s (2009) article where he analyzed the skills called for in recruitment postings for technical writers on the job board Monster.com. To expand his research, I compared job ads on three other job boards I used most often when I was a recruiter in the corporate world. As a recruiter, I did not use the job board Monster.com because of its limitations; therefore, I did not use it for this study. Instead, and for the sake of an equitable comparison, I used the same categories and subcategories Lanier (2009) specified in his research to investigate the three job boards I did use as a recruiter.

- I summarized research on academic requirements in technical/professional writing programs done by Meloncon and Henschel in 2013 and compared their findings to my findings about job-ad requirements. Meloncon and Henschel reported on 65 undergraduate programs in technical and professional writing across the United States and learned that there are specific, identifiable courses that serve as core requirements for most.

Understanding what skills and experiences recruiters and hiring managers are searching for in new employees can help guide academia as program directors make decisions about their curriculum. Additionally, comparing technical/professional writing program requirements directly to job board postings can add support for decisions made by program directors and faculty as they try provide a robust program that offers breadth and depth of knowledge to students and prepares them for the workforce as seamlessly as possible. Knowing what industry requires has many implications for technical/professional writing programs and the research we do as we think about curriculum requirements and program assessment. Because my professional career has allowed me to be a teacher of technical writing at the university, to then move to the corporate world and hold titles of technical writer, recruiter and manager of technical writers, and then to go back to being a teacher at the university, I have a special view of what technical/professional writing students need to know and how we can best teach those skills in our programs. Likewise, I have an appreciation for technical/professional writing programs and the need for these programs to be continually assessing their effectiveness in preparing students to be the most valuable new employees they can be.

Surveys from Hiring Managers and Recruiters

To learn what hiring managers and recruiters were looking for when hiring entry-level technical writers, I conducted a survey with five professionals who regularly hire technical writers. I solicited them via email, and they completed and returned the surveys through email. Items on the survey included demographic information about which industries and in which cities and states these participants hired technical writers, and the survey began with an open-ended question, “What are the top 3-5 skills you seek in any candidate?” Respondents were told the skills could be technical skills, software skills, or soft skills. Other questions asked what kind of items candidates should include in their portfolios, whether it mattered if candidates majored in a particular discipline in college, and which soft skills were the most important. They were also asked if there was something in a job application that made them reject a candidate. The entire survey can be found in Appendix A.

Job Postings and Job Boards

In addition to the surveys, I wanted to learn what skills and experiences were required for entry-level technical writing positions. I collected job ads from three different job boards, Indeed.com, CareerBuilder.com, and DICE.com, from August 31, 2015 to October 28, 2015. I used these particular job boards because they were ones with which I was most familiar; however, the reviews and focus of the jobs posted on these sites support their value for entry-level technical writers.

In his article, Lanier (2009) questioned the accuracy of job ads and said they may be more of a wish list that managers had rather than true “requirements”; however, this was not the case in my experience as a recruiter. I worked as a recruiter at a small start-up computer software company that was purchased by one of the world’s largest consulting firms, where I also did recruiting, and even if I had to use the company’s job descriptions to create job postings, I still made time to have a meeting with the hiring manager to ensure the skills the manager needed were stated in the job posting. Many times managers wanted too many requirements as well as “preferred” requirements listed in the job ad, but the goal was to include only four to eight “must haves” as requirements. Because I vetted the job requirements with the hiring manager, the job postings I submitted were authentic and not just a wish list. I understand that not all recruiters at all companies are able to implement this process when posting a job. Some recruiters may not have access to the hiring manager and must use only the job description in the company’s database, but the posting would still likely be based on documentation created by the company and not just a list the manager creates.

One limitation in Lanier’s study (2009) was that he used only Monster.com as his job posting source because “most employment posting search engines perform the same functions” (p. 53). All job boards are not the same, however, and recruiters have many options when choosing where to post job openings for the company. When I was recruiting, I most often used CareerBuilder.com, Indeed.com, and DICE.com. I stopped using Monster.com in about 2005 because it got the lowest return on investment for my recruiting efforts.

According to the article “Undercover Recruiter” (n.d.), which informs job seekers which job boards are most useful to them specifically, the authors note that CareerBuilder.com is the job board that has more candidates that have college degrees (para 3). Another article states that CareerBuilder is more focused than Monster.com (Dada, 2013, para 4).

In a comparison between Monster.com and InDeed.com, one author claimed that Indeed is simpler to use than Monster.com (Montana, 2015, para 3). At the time I was recruiting, Indeed.com, which was started in 2004, was new and not filled with a large number of inactive candidates, so more active candidates were applying for positions (Bergen, 2012).

In addition to technical writing positions, I posted computer programmer and database programmer positions on DICE.com. This job board is advertised as a good option when filling positions for technical writers because this job board is particularly geared toward more technical positions, “like . . . tech writers” (“Undercover Recruiter,” n.d., para 7).

It was always important for me to choose the best job board for the position being recruited in order to meet budgets and quotas for numbers of interviews and hires. Based on the focus and population of users of the three job boards to which I posted jobs when I was recruiting, it is Career Builder, Indeed, and DICE that are most relevant for a study investigating job ads for newly graduated technical writing students looking for positions where they will use the degree they just received.

Because I was expanding Lanier’s (2009) article to include other job boards besides just Monster.com, and because I wanted the data to be as equal as possible for the purpose of comparisons, I collected and analyzed data using the same categories and subcategories he did. The categories and subcategories are named in the data in the Findings-Job Posting section in Figures 3 through 7 below. As mentioned, I also used the same query as Lanier, searching for only the term “technical writer.” My goal was to conduct a fair and accurate comparison to Lanier’s findings and to learn if there were differences in other job board postings. I recognize that there are many titles a person working as a technical writer can hold and that describe a technical writer. In fact, Brumberger and Lauer (2015) conducted a study looking at more titles, which also involved a more “extensive range of competencies, products, technologies, and traits” (para 17); however, because the jobs represented by these titles would likely go beyond the skills of a new graduate looking for an entry-level position, I did not include other titles in my searches. For this study, I wanted to investigate job boards that would be a better representation and more useful to new college graduates, in order to learn whether the job requirements were similar across job boards, and whether they correlated well to the academic technical/professional program requirements.

Findings – Surveys from Hiring Managers and Recruiters

The responses to surveys came from five professionals who hire technical writers. Respondents #1 and #2 were corporate recruiters at one of the world’s largest consulting firms, and they recruit for different industries across the company. Respondent #1 described her recruiting assignments in the following way: “I have hired tech writers for Network and Software-based positions for both End-user documentation/training and technical systems documentation.”

Both Respondents #3 and #5 work on a documentation team for a software company and have assisted with interviewing and hiring technical writers. Respondent #4 is the manager of a team of technical writers and has interviewed and hired technical writers. In addition to conducting or assisting with conducting interviews during the hiring process, Respondents #3, #4, and #5 have also been involved in specifying requirements for technical writers and helping with wording for the job ad.

After collecting basic demographic information about which industries and in what cities and states these participants hired technical writers, I asked the open-ended question, “What are the top 3-5 skills you seek in any candidate?” (Respondents were told the skills could be technical skills, software skills, or soft skills.) All answers given by the respondents are recorded here.

Respondent #1 (Recruiter)

- Technical acumen specific to the type of project, leadership/project management (ability to drive a project forward, communication with technical team, accountability to leadership)

- Attention to detail

- General writing skills

Respondent #2 (Recruiter)

- Previous technical writing experience, backed up by portfolio

- Bachelor’s degree in applicable major (technical/professional writing or English)

- Good written and verbal communication skills

Respondent #3 (Employee on team who helps hire)

- Technical writing background

- Editing

- Experience with creating online content

- Basic HTML

Respondent #4 (Manager of team)

- Demonstrable writing skills

- A passion to help others succeed

- Strong interviewing skills

- Ability to work well in both group and independent settings

- Strong interpersonal/communication skills

Respondent #5 (Employee on team who helps hire)

- Exceptional writing skills

- Technical knowledge

- Knowledge of programming languages

- Familiarity with HTML

- Soft skills – The candidate needs to be a team player who can adapt to various personalities and situations. I look for someone who will fit well with the company and the Technical Communications team.

- Organization, self-motivation, and problem-solving skills are also desired.

When asked if they would interview an applicant who had all the skills required for a position except the software skills called for, only one (Respondent #3, an employee who helps with hiring) said she would not conduct the interview. All other respondents would give the applicant a chance and would conduct an interview.

All respondents noted that soft skills are an important consideration when interviewing candidates. The following soft skills mentioned specifically as the most important were

- Motivation to help others

- Strong interviewing skills

- Independence

- Strong interpersonal/communication skills

- Adaptability

- Problem-solving skills

- Teamwork

Additionally, all the respondents said that if a college degree were a requirement for the position, the major area of study did matter, and it should be English or Technical/professional communication. One respondent also mentioned that some technical coursework would be beneficial but did not specify what that should include.

Four respondents said that having a master’s degree would not put a candidate ahead of others applying for the same job. Respondent #4, a Hiring Manager, said that when he vetted candidates, the master’s degree could put a candidate above others, but only in the sense that it served as evidence that the candidate is “willing to spend two more years getting further educated, [and] … is passionate about [his/her] craft and is motivated to do the job well” (Respondent #4, survey data).

All respondents stated they would require a portfolio and would be looking for the following artifacts and evidence:

- Writing for a variety of audiences, writing that shows being able to adapt to different project needs (e.g., instructional piece, a design piece [like a brochure], a research essay, and something created for the web)

- Items that showed a consistent writing style

- Samples of editing

- Samples of work that was created using different applications (e.g., Illustrator, Dreamweaver, Visio)

The similarities in the answers given by hiring managers and recruiters are noteworthy. In addition to the findings of the survey, I investigated requirements included in entry-level job ads in three different job boards.

Job Ad Requirements

Lanier (2009) conducted a study using 327 job ads for technical writers and used only the query “technical writer” on the job board with a goal to make the study “more significant” to the field of technical communication (p. 53). In a more recent article, Brumberger and Lauer (2015) state that when they looked at 1000 job ads on Monster.com, they used different queries for their study because “practitioners and academics take the position that technical writers are not—and have not been for some time—just writers” (para 3). While this is true, the five different categories of jobs identified by Brumberger and Lauer (2015), “technical writer/editor, content developer/manager, social media writer, grant/proposal writer, and medical writer” (para 31), would potentially have different specialized requirements that an entry-level “technical writer” would not yet possess. Because my study was looking for requirements for a job candidate who had recently graduated from college with a degree in technical/professional writing, I queried as Lanier did, using only “technical writer.” Also, because I wanted to be able to compare Lanier’s findings with my own, I did not include jobs that required a “specialized, technical degree (such as chemistry or engineering),” which is also how Lanier coded his findings (p. 53). Lanier’s study revealed nine skills or tools called for most often in the job ads. I have summarized the results of his study in Table 1 below.

Data Collection from Job Boards

Using just the query “technical writer,” I collected data from job postings on the three job boards mentioned. This is a substantive difference from Lanier’s (2009) study: he used a job board that many recruiters no longer use and that includes position postings that do not usually require four-year college degrees. The three job boards I investigated all focus more on positions requiring a college degree and include more positions that would list similar requirements to that of an entry-level technical writer. Next, I conducted a content analysis of each job posting, noting the experience, skills, software tools, project-management skills, and soft skills listed for each job. If specific tools were mentioned, such as specialized graphics, publishing, or online help software, these were coded and documented separately. Similar to how Lanier (2009) coded his data, I coded specific experiences as technical communication experience, subject-matter expertise, and technical knowledge and experience. If a job posting called for the Microsoft® Office Suite, I coded that in the category of General Software Knowledge.

Table 1. Summary of findings about job ads from Lanier’s (2009) article

|

Skills or Tools called for in the job ad |

Percentage of Ads |

Explanation of Skills or Tools sought |

|---|---|---|

|

General software tools |

64% |

MS Office or mention of computer knowledge |

|

Excellent communication skills or a firm grasp of the English language |

39% |

Oral and written communication skills |

|

Technical writing experience |

38% |

Previous (general) technical writing experience |

|

Subject matter experience |

33% |

Experience actually writing about the subject matter in the job |

|

Specific subject matter experience |

34% |

Experience in the subject matter |

|

Specialized desktop publishing |

34% |

Examples: FrameMaker or InDesign |

|

Specialized genre familiarity |

24% |

Particular types of documents such as standard operating procedures |

|

Markup Languages |

17% |

HTML, SGML and XML |

|

Computer Languages |

7% |

C++, Java, and C# |

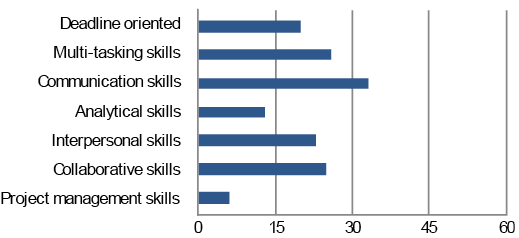

Lanier (2009) categorized project-management skills as collaborative, interpersonal, analytical, communication, multi-tasking, and deadline-oriented skills. In their study, Brumberger and Lauer (2015) labeled these similar requirements as personality characteristics. While I included these skills in the same category as Lanier did, I changed this category slightly and coded these requirements as soft skills. I was surprised that many times, there were more requirements for soft skills included in a job ad than technical skills. Because they appeared so many times in the job postings I saw, I added two skills that were not included in Lanier’s (2009) categories: namely, organizational skills, which I coded as project-management skills, and English/grammar skills, which I coded as communication skills.

I looked at sixty job ads, twenty from each of the job boards to see if there was enough of a difference between the job ads on Monster.com and the job ads found in CareerBuilder.com, Indeed.com, and DICE.com to warrant a call for more research and investigation in the different job postings. When I used the query “technical writer,” other job titles that appeared in the results were Proposal writer, Report writer/Data analyst, Marketing proposal writer, Service writer, Documentation analyst, Integration technical writer, Policy & procedure writer, and Instructional designer/writer. As I have mentioned already, I did not include data from these job titles because I was looking for job requirements for just the title “technical writer.” I also did not include data for jobs that were listed as temporary positions or that were positions for a short-term contractor. It could be that requirements are different for those positions. For this limited study, I focused on full-time positions.

While it is unlikely that a recruiter would post the same job in different job boards because of costs and because each job board usually focuses on a different area and targets a different audience, to avoid replication of the same job postings, I recorded the date of my search, the job board, industry, and company name for each posting, as well as the requirements of the job ad. This helped ensure that I was not duplicating the same position posted in different job boards. If any discrepancies or duplications were discovered, they were easily detected and eliminated.

After collecting data from job ad postings on job boards, I was able to compare those findings to the data from the survey that corporate recruiters and hiring managers completed, which included answers to questions about their processes. This is valuable information to have because it is the recruiters and hiring managers who ultimately decide which candidates to interview and eventually hire. In addition to these comparisons, and to answer my research questions about whether programs prepare students well for the workforce, I also compared the job ad requirements to the curricula in technical/professional writing programs to see if the programs are teaching students what it is that industry is looking for as they hire entry-level technical writers.

Findings – Job Ads

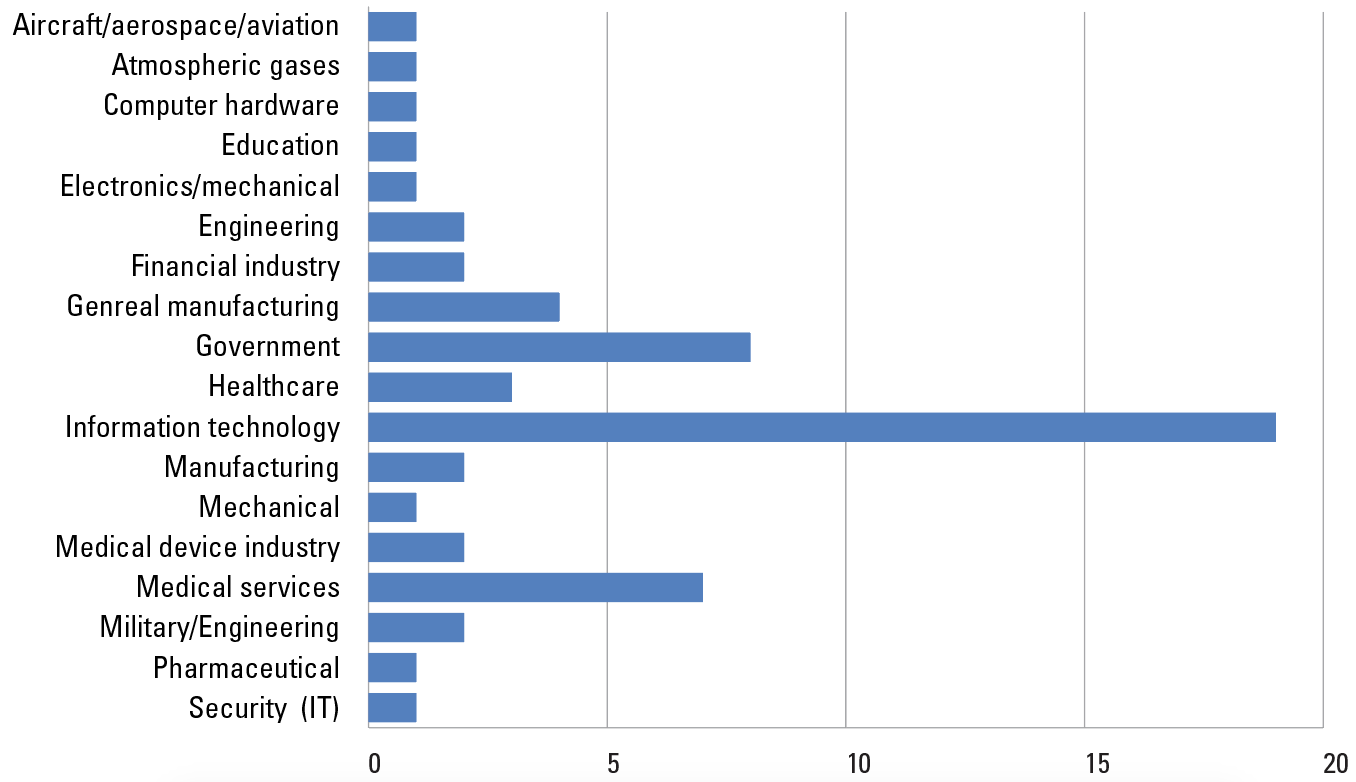

Out of the job postings analyzed, the industries represented were varied and did not necessarily correlate to Lanier’s (2009) findings. Figure 1 shows the distribution of industries represented in the job ads in this study:

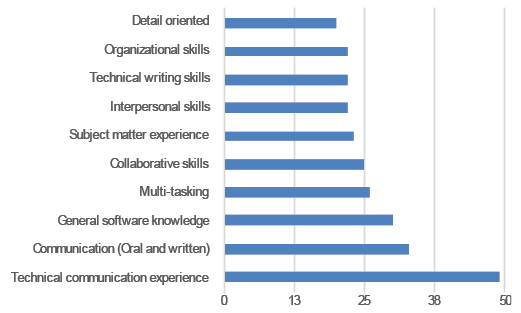

In the sixty job ads I collected and analyzed, the most sought-after experiences or skills are shown in this list and in Figure 2 below.

- Experience in technical communication, 82% of the postings.

- Communication, 55% of the postings. The term “communication” was not well defined in the job ads. Sometimes the job ad listed “oral” and “written” communication. I also labeled a “good grasp of the English language” in this category.

- General Software knowledge, 50% of postings. I placed anything that called for Microsoft Office tools or a mention of computer skills or general computer skills (without further specifics) in this category.

- Multitasking, 43% of the job ads.

- Collaboration skills, 42% of the job ads.

- Subject matter experience, 38% of the job ads. Subject matter experience was defined by Lanier (2009) as “experience with the subject for which, or about which the candidate will be writing” (p. 56).

- Interpersonal skills appeared as many times as did the call for subject matter expert (38%).

- Technical writing skills, 37%

- Detail oriented, 33% of the ads

- Organizational skills, 7%.

These experiences and skills are displayed in Figure 2.

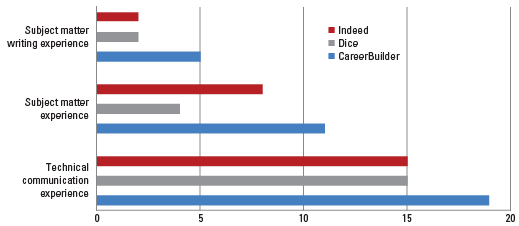

I also looked at the main categories coded in the data and then separated that data by job board to see if one job board favored different skill sets over the others. The category “experience” had the subcategories of subject-matter experience, subject-matter writing experience, and technical- communication experience; the breakdown of the different job boards is shown in Figure 3.

The categories were represented across the job boards almost equally except for the sub-category of subject-matter experience. It showed up fewer times in the DICE.com job ads than in the other two job board ads.

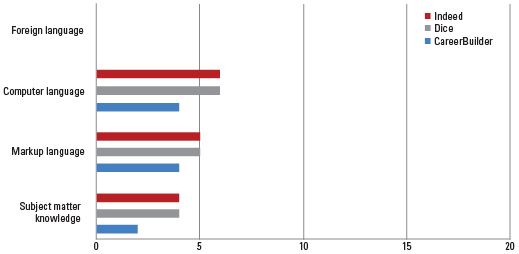

The next category was technical knowledge/experience. Subcategories included computer language knowledge/experience, markup language knowledge/experience, subject-matter knowledge, and foreign-language knowledge. Lanier (2009) noted that foreign language was required in five of the ads he collected. While Barbara Giammona has said that a minor in a foreign language would give a student an advantage over other candidates vying for the same position (as cited in Rainey, Turner, & Dayton, 2005), none of the job ads I analyzed listed fluency in a foreign language as a qualification or preference. Figure 4 shows the summary of the technical knowledge/experience category.

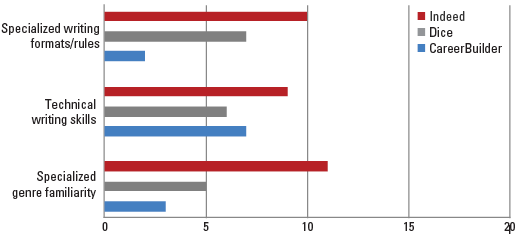

The category of technical writing-specific knowledge refers to specialized writing formats and rules, or specific knowledge about genres. Lanier (2009) defined these as “Knowledge of specified, specialized writing formats or rules, such as ISO 9,000 standards, MIL-SPEC, or Aircraft Industry Standards” or “Familiarity or proficiency with unique or particular genres, such as SOP’s, grant proposals, or software documentation” (p. 56). The summary of the technical writing-specific knowledge is shown in Figure 5.

The sub-categories of specialized genre familiarity and specialized writing formats/rules were listed fewer times in the CareerBuilder job ads than in the other job board ads; however, technical writing skills showed up approximately the same number of times across all job board ads.

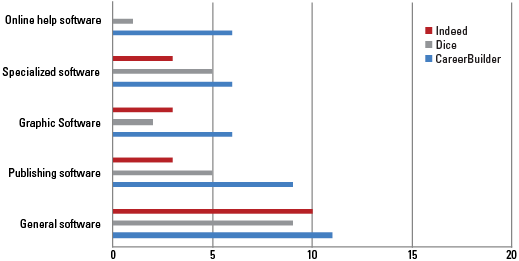

The category of technology or tool knowledge includes the sub-categories of technical-writing skills, specialized publishing software, specialized graphics software, online help software, general software knowledge, and specialized software knowledge. CareerBuilder job ads mentioned these tools and knowledge/skills most often. The summary of the tool knowledge/skills is represented in Figure 6.

Interestingly, soft skills were called for more often than other skills. Lanier (2009) identified subcategories for these to include collaborative skills, interpersonal skills, analytical skills, communication skills, multi-tasking skills, and deadline–oriented skills. Because I discovered several instances of organizational skills and a call for a strong grasp of English and grammar skills, I included these terms in my coding schema. Figure 7 summarizes the soft skills category and sub-categories.

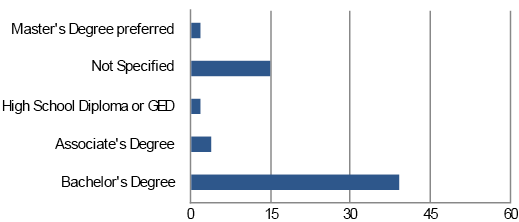

Education was specified in three quarters of the sixty job postings. A bachelor’s degree was specified in 39 of the job ads. One ad indicated a bachelor’s or master’s degree was required, and two of the ads stated that a master’s degree was preferred. Figure 8 shows the education required in the job postings.

It is also noteworthy that the job ads were representative of different cities and states across the entire United States. States specified in the job ads were Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington, and Washington, DC.

As a summary of the skills sought in job ads, and also how students would be able to acquire those skills within their academic experience, I have provided the following table as a comparison.

It is important to realize that for each of the requirements in the job ad, there is a class or experience in the technical/professional writing program that provides an opportunity for students to learn and/or have experience with the requirements.

Table 2. Comparison – Job ad skills versus skills taught in TPW programs

|

Skills sought in job ads |

Courses and experiences that would include this skill |

|---|---|

|

Experience in technical communication |

Internship, field experience, completing assignments in several classes |

|

Communication skills (good grasp of the English language) |

Basic, Introductory, Capstone, Internship, Web |

|

General software knowledge |

Web, Document design, Internship |

|

Multitasking |

Capstone, Internship |

|

Collaboration skills |

Internship, Many classes that would include group projects/assignments |

|

Subject matter experience |

Genre, Internship, Web, Document design |

|

Interpersonal skills |

Internship, Any class that requires group work |

|

Technical writing skills |

Basic, Introductory, Genre, Editing, Document design |

|

Organizational skills |

Basic, Introductory |

|

Detail oriented |

Editing |

Program Requirements Across the United States

If the goal of an academic program is to produce students who have a breadth and depth of knowledge in their field of study, with the goal of transferring as seamlessly as possible into the world of work, it would make sense that the world of work would have a voice in what the students were taught. This relationship between industry and academia is crucial yet difficult to establish and nurture. And while some in academia may want input from industry, there must be a balance between getting input from industry and still having the freedom to be creative and develop a program that is exactly what students need, as decided by the program director. Harner and Rich (2005) said it well: There is not a typical curriculum for a technical/professional writing program (p. 209). Johnson-Eilola (1996) notes that the technical communication program is often “called upon to fulfill wish-lists of skills” for industry, a role that those in academia may find too restrictive and demanding (p. 247). One way we might be able to receive input from industry while maintaining autonomy as a program would be to invite people from industry to serve on advisory boards.

Some academic programs embrace input from an advisory board, which can be helpful and can infuse energy into the program, but others steer clear of them. Meeder and Pawlowski (2012) tell about a business advisory board that provided a transformation for their program; they felt the board added a benefit in helping program directors know better what students needed in order to be well equipped to go into the workplace. Other program directors do not want to be supervised by non-academic or extracurricular entities.

While there is no typical technical/professional writing program curriculum, research has been conducted on many programs across the United States. Program directors can learn about already-established programs to help them make informed curriculum decisions. The first study was conducted in 2005 by Harner and Rich and included 80 programs. A set of core courses was identified, and the authors discussed the locations of the programs, requirements for internships, and the development and inclusion of portfolios. Later, this research was updated by Meloncon and Henschel (2013), who studied 65 programs across the U.S. and provided an update, comparison, and summary of program information that Harner and Rich had compiled previously. Meloncon and Henschel (2013) contend that their research “provides the field its first opportunity to compare curricula over time and to highlight trends and changes” (p. 55). Both of these studies employed a research methodology in which the researchers accessed the universities’ web sites and course catalogs and collected information about programs and courses there. Harner and Rich (2005) identify an obvious weakness in this methodology: that is, “the accuracy of the information retrieved is in direct proportion to the accuracy of the information on the Web sites” (p. 210).

In the 65 programs in Meloncon and Henschel’s (2013) study of technical/professional writing undergraduate degree programs across the U.S., they found eight main courses that were required by 40% of the programs; they labeled these as the core requirements taught in the technical/professional writing discipline. Beyond those eight courses, the study found multiple elective options. In addition, the study found 58% of these programs also require a minor, subject-matter focus, or professional experience. Most of the minors required 15-18 additional credit hours beyond the major requirements (p. 54).

Meloncon and Henschel (2013) reported the eight main courses required were Basic, Capstone, Editing, Internship, Introduction, Web, Document design, and Genre (p. 51). To better understand what universities include in the curriculum of each of these courses, Meloncon and Henschel provided the skills from each university’s catalog as a summary of the curricula taught in the courses. These skills are listed in Table 3 below.

Table 3. Summary of Meloncon & Henschel (2013) Program Requirements

|

Course |

Skills |

|---|---|

|

Basic |

Audience analysis, Composing technical discourse |

|

Capstone |

Cumulative experience, Portfolios |

|

Editing |

Levels of editing, Process of editing through publication |

|

Internship |

Field experience |

|

Introduction |

History, Theories, and definitions in TPW, Page design, Research tools, Genres & conventions |

|

Web |

Tools and technologies of content production, New and multi-media, Page layout, Design principles |

|

Document design |

Write and design documents using electronic publishing technologies |

|

Genre |

Proposals/grants, Instructions, Reports, Public Relations, Marketing, Government or industrial, Medical and/or environmental |

These eight courses provide instruction in skills necessary for the scope of academic offerings, beginning with foundational courses and moving to the more expert-level skills and experiences for the technical/professional writing student.

It should be noted that while a set of core skills has been identified, vast differences in programs remain. One example is the Internship course. Meloncon and Henschel (2013) noted the difficulty in “manag[ing] and sustain[ing]” (p. 60) internships. Also, faculty advisors and program directors must maintain connections with established employers who provide their students internship opportunities. In addition to these responsibilities, faculty advisors and program directors also must assess student performance within the internship experience. Another issue with the internship requirement is described by Savage and Seible (2010). In their study, they investigated 63 TPW programs: of the programs that required an internship, the required number of hours in the workplace varied significantly. Some required as few as 1–40 hours, while others required as many as 1001–1040 hours. The majority of the internships (54%) required 81-160 workplace hours to fulfill the requirement of the internship (p. 63). The kind of work required varied as well. Savage and Seible (2010) suggested that an intern who works for 100 hours completing primarily copyediting work should not earn the same credit hours as a student who is working on complex documents that require more advanced competencies, such as design and interpersonal skills (p. 61). This would be an area for further study. Directors of internships should scrutinize the tasks assigned to an intern, and potential employers should be aware that not all required internships are the same.

Variation in TPW programs is also evident on the position of software and hardware in the curriculum. Program directors and faculty still cannot agree on whether to teach specific tools and technologies. Some argue that students must learn specific tools; others recommend that it is more important that students have a familiarity with several tools but are skilled at learning new tools. Rainey et al. (2005) echo the attitude of many of the hiring managers with whom I used to work: “The ability to adapt to new situations and to learn new software quickly is far more important than knowledge of specific software packages” (p. 333). In their study, one respondent noted, “Basically, if I can find a superb writer who understands technology and works well with others, I am willing to provide training for all the other skills I need the person to have” (p. 333). This same sentiment was expressed by respondents in my study when they said they would interview candidates lacking technical experience and give them a chance.

Rainey et al. (2005) reported that in addition to the main requirements, most programs encourage students to focus on an area of technology or science for the required electives or for a minor. Even when a set of classes can be described as “core,” there are still many differences in program requirements. Having a good understanding of what employers want in a recently-graduated employee can help inform the required curricula within these programs.

Discussion

After looking at

- the requirements listed by recruiters and hiring managers who actually hire technical writers,

- the requirements posted in entry-level technical writing job ads, and

- the Meloncon and Henschel (2013) report of requirements within the curricula of TPW programs across the United States,

I conclude that many TPW programs in the United States are addressing the needs that employers have by offering courses that meet those needs. While there are differences in the details, it appears the major objectives in technical/professional writing programs seem to be more consistent than not. Foundational courses offer students a broad base of the different genres technical writers use, including technical reports, proposals, and instructions. Document design and web design courses often include usability and user-experience tasks as part of the curriculum. It could be argued as well that because of the access most college students have to technology, the majority of college students in the U.S. have more than just a general knowledge of software options.

Whether programs should teach specific tools or teach students how to learn tools continues to be a debated topic; regardless, some tools are being taught as part of the curricula in most TPW programs, and faculty and program directors will have to make decisions about how to balance this most effectively for their students. As a former recruiter, I concur with Rainey et al. (2005), who advocate that students should be required to learn and to use different software tools to complete projects. If, in an interview, a student’s portfolio includes a well-done, final product that was created after using a new application for only a few weeks (especially with little formal instruction), this is valuable. Students who can learn on their own will require fewer hours of direct training. Students who can prove they are self-motivated learners will have an advantage because managers and other employees are often too busy to train new employees, even when they are behind with projects and need new team members.

Interestingly, Rainey et al. (2005) suggest that “relevant tools should include language – and especially foreign language” (p. 323), but in my findings, no job board, manager, or recruiter mentioned the need for a potential employee to know a language other than English. This is surprising because in today’s economy, many companies have offices worldwide.

Communication skills and technical writing skills will be taught in academic courses as well, and several courses will have a collaborative component to give students collaboration skills, organizational skills, and interpersonal skills. Being able to multi-task and pay attention to detail may be personality traits, but these can be improved on with practice. Subject-matter experience may be gained when students complete the required 15-18 credit hours with a minor, subject matter focus, or professional experience that is required in the 58% of the 65 programs studied by Meloncon and Henschel (2013).

It is important to remember that when hiring managers are considering a potential candidate for a new position, they and recruiters should look at the whole package the candidate brings to the table and not just the course work in the program where the specific degree was acquired. In addition to their course work, many students also hold down jobs and participate in extracurricular activities. Some of them do all of this and maintain a better-than-satisfactory grade-point average (GPA). These extra responsibilities are important to think about and can help students acquire many of the skills the employer seeks.

While this is a valuable study, it is a small-scale study with a low but expedient number of participants and job boards. Additionally, the program data collected by Harner and Rich (2005) and later updated by Meloncon and Henschel (2013) is only as good as the universities’ web sites from where they accessed the data. And it is likely that not all technical/professional programs are included in the data; there may be important data missing that could add to these results.

Conclusion

Ensuring the employability of students is a goal of the university experience; therefore, TPW program directors need to stay current on technologies and methodologies used in the workplace and provide the foundation and the opportunities for students to learn these in order to be employable. In addition to teaching technologies and methodologies, instructors must keep up with what kinds of assignments most effectively teach students these necessary skills.

It is also important to understand that students cannot learn all the skills and experiences they need from a class. For example, multitasking is not likely to be the title of a course, but students have the opportunity to learn soft skills with every class meeting and class project within their course work. Considering the response about how important soft skills are to recruiters and hiring managers, we need to emphasize soft skills more in the curriculum. Additionally, many of the TPW programs included in this study require an internship, which can offer valuable experiences for students; however, more study needs to be done so we can learn about internship requirements, how we can align these better from program to program, and how we can encourage employers to accept internship hours as legitimate workplace experience. Employers also need to understand that there may be vast differences in internship requirements from one program to another. Still, it is satisfying to realize most programs are offering technical/professional writing students with the skills and experiences they need to be considered as valuable entry-level employees in the work force.

References

Bergen, J. (2012, June 15). “Q&A: Indeed’s co-founder gives job search tips.” PC Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2405749,00.asp

Brumberger, E., & Lauer, C. (2015). The evolution of technical communication: An analysis of industry job postings. Technical Communication, 62(4), 224-243.

Dada, U. (2013, January 11). “Jobs available: Two popular employment sites go head-to-head.” Direct Marketing. Retrieved from http://www.dmnews.com/features/jobs-available-two-popular-employment-sites-go-head-to-head/article/275745/

Harner, S., & Rich, A. (2005). Trends in undergraduate curriculum in scientific and technical communication programs. Technical Communication, 52(2), 200–220.

Johnson-Eilola, J. (1996). Relocating the value of work: Technical communication in a post-industrial age. Technical Communication Quarterly, 5(3), 245–270.

Lanier, C. (2009). Analysis of the skills called for by technical communication employers in recruitment postings. Technical Communication, 56(1), 51–61.

Meeder, H., & Pawlowski, B. (2012, February). Advisory boards: Gateway to business engagement. Techniques, 28-31. Retrieved from http://bluetoad.com/publication/?i=97021&p=28

Meloncon, L., & Henschel S. (2013). Current state of U.S. degree programs in technical and professional communication. Technical Communication, 60(1), 45–64.

Montana, S. (2015). “LinkedIn vs. Monster.com vs. Indeed: For employers, which job postings work best?” Knoji Consumer Knowledge. Retrieved from https://jobsearch.knoji.com/linkedin-vs-monstercom-vs-indeed-for-employers-which-job-posting-works-best/

Rainey, K., Turner, R., & Dayton, D. (2005). Do curricula correspond to managerial expectations? Core competencies for technical communicators. Technical Communication, 52(3), 323–352.

Savage, G., & Seible, M. (2010). Technical communication internship requirements in the academic economy: How we compare ourselves and across other applied fields. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 40(1), 51–75.

Undercover Recruiter. (n.d). “Which job boards are most useful for applicants?” Retrieved from http://theundercoverrecruiter.com/job-boards-useful-jobseekers/

About the Author

Rhonda Stanton is an assistant professor and the director of the technical and professional writing program at Missouri State University, where she also sponsors a student chapter of STC. Her experiences in the corporate world include technical writing, facilitating performance management initiatives, training new employees and clients, and recruiting. Her research interests focus on recruiting and managing multigenerational groups and pedagogy in technical writing, including service learning. She received her PhD from Texas Tech University. She is available at RhondaStanton@MissouriState.edu.

Manuscript received 28 January 2016, revised 15 June 2016; accepted 19 October 2016.

Appendix A

Survey Sent to Recruiters and Hiring Managers

Thank you for answering these questions. They should take you only about five to ten minutes. Your participation is not required, and there is no risk for you to participate. You may stop answering the questions any time (or leave any blank that you don’t wish to answer).

- For what industry (or industries) do you recruit/hire technical writers?

- What city/state would the technical writer work in? (Or has worked in, if you hired one)

Skills

- What are the top 3-5 skills you seek in any candidate? (This could be technical skills, software skills, or soft skills.)

- Do you typically look for software skills in an applicant?

- Would you be interested in interviewing someone who had all the skills except software skill/experience you might require?

Soft Skills

- How would you define soft skills?

- Do you look for soft skills in a candidate?

- If yes, which one(s) particularly?

College Degrees

- If the job requires a Bachelor’s Degree – does it have to be with a specific major or minor?

- If yes, what is that major?

- Does is matter if a candidate has a Master’s Degree?

- If yes, how does it differ?

- Would an applicant with a Master’s Degree have an advantage over one that has only a Bachelor’s Degree?

- Do you value Master’s Degrees more than Bachelor’s Degrees?

- What differences do you observe in the workplace in a worker with a Master’s Degree as opposed to a worker with a Bachelor’s Degree?

Portfolios

- Do you require a portfolio of applicants. Yes/No.

- If no why not?

- If yes, does HR look at it? Or the hiring manager? Or maybe both?

- If you collect a portfolio, do you prefer hard copy or online?

- What are 3-5 items you expect to see in a portfolio of a TW applicant?

Social Media

- When considering a candidate for a TC job, do you look at his/her social media sites?

- Do you believe what you see in social media gives you an idea of what kind of employee someone will be?

- If yes, can you give a little more explanation?

For the Manager

- Do you have a Bachelor’s degree?

- If yes, what was your major (and minor)?

- What degrees do most of your workers have and what majors?

Last Questions

- What is something that makes you reject a candidate?

- Is there anything you would like to add about hiring technical writers?