By Michele Mosco

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Students enroll in college to gain expertise for the workplace. Students are trained in academia to avoid plagiarism by citing sources and refraining from copying others’ written works. However, in workplace writing and technical communication, common workplace practices reuse, repurpose, and remix content of works authored by others. Unfortunately, this causes a significant disconnect between what students learn and how this learning applies in the workplace. The following questions guided the study:

- How do the latest editions of widely used technical communication textbooks in the United States teach students about plagiarism, collaboration/authorship, copyright, and ethics?

- How do the approaches used in textbooks align with workplace practices?

Method: In the first phase of the analysis, each textbook was searched to locate any depictions of plagiarism, collaboration/authorship, copyright, and ethics as they relate to the workplace. Then a qualitative content analysis was conducted using a rating scale developed incorporating suggestions researchers made on how to best teach plagiarism and copyright infringement avoidance.

Results: Each of the eight texts was rated on each criterion with a possible total of 30 points. Most texts scored 10 or less, one scored 12, and two of the texts scored 15 or above. The extent to which introductory textbooks address each of the criteria was generally abysmal. The texts largely did not address common types of workplace writing and how copyright and plagiarism apply in those situations.

Conclusion: The majority of widely used introductory technical communication textbooks do not thoroughly and clearly explain plagiarism, collaboration/authorship, copyright, and ethics in workplace writing. Additionally, these textbooks do not present context-specific scenarios to which students can apply this information. However, several of the texts do provide examples of workplace activities that contradict academic views of authorship.

Keywords: Plagiarism, workplace writing, technical communication, authorship, and copyright

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Most technical communication textbooks continue to emphasize avoiding plagiarism and “copying.” However, this emphasis is problematic because workplace writing often incorporates work written by others. Specific examples include the use of boilerplates/templates, single-sourcing, content reuse, collaboration, and ghostwriting.

- Whether or not the students’ understanding of these topics increases after completing more advanced writing courses is unknown.

- New graduates will likely need mentoring when they enter the workplace to develop their understanding of the nuances of copyright and plagiarism applied to their work.

INTRODUCTION

As early as kindergarten, children are taught not to copy others’ work. In third grade, for example, the term plagiarism is introduced as using another person’s works or ideas without proper credit, and plagiarism is “bad” (Common Sense, 2018). According to the Common Core State Standards (2019a & 2019b), which guide instruction in 41 states, fourth-grade students must provide a list of sources for their written work. The emphasis on avoiding plagiarism and copying continues through high school, where the consequences of plagiarism are more serious. When students enter college, they must adhere to a code of conduct or an academic integrity agreement. Enumerated are the ways in which a student can violate this code, leading to a series of increasingly grave penalties (which may not actually occur, but that is the subject of another study). Researchers have noted that students are often confused about the differences between plagiarism and copyright as well as the specific actions that are allowable (Auman, 2014; Marshall, & Garry, 2005; Rife, 2010, 2013).

Because plagiarizing or infringing on copyright can have dire consequences for someone in the workplace, it is important for students to understand how to avoid these in their writing. Not only are there legal consequences for infringing, damaging the reputation and integrity of both the writer and his/her employer can have serious financial effects. Therefore, an understanding of how to avoid plagiarism and copyright infringement is important.

In “Rethinking Plagiarism for Technical Communication,” Reyman (2008) was one of the first researchers to argue that the emphasis on citing sources and refraining from copying others’ written works is problematic in the field of technical communication by the very nature of the types of writing technical writers produce. Later researchers agreed (Louch, 2016; Zemliansky & Zimmerman, 2014). Students enroll in college to gain expertise for the workplace. Unfortunately, in many instances, there is a significant disconnect between what students learn and how this learning applies in the workplace.

But this problem affects more than just those employed as technical writers or technical communicators. Instead, as Kimball (2017) argues, “much of the rest of the world’s population is actually engaging in the act of technical communication every day” (p. 340). Indeed, the Society for Technical Communication (STC, 2018a) defines technical communication as “any form of communication that exhibits one or more of the following characteristics: Communicating about technical or specialized topics. . .Communicating by using technology. . .Providing instructions about how to do something. . .” This means universities need to consider that although students may not be destined for employment as “technical writers,” it is highly likely they will develop technical communication in their future workplace.

Non-technical communication majors may find themselves in an introductory technical communication class or a service course, which are “the introductory courses for non-majors delivered primarily as a service to other departments or programs on campus” (Meloncon & England, 2011, p. 398). For some students, then, the introductory course may be their only exposure into specific technical communication content and their last writing course before leaving the university.

While it is true that specific practices and procedures vary from company to company, it is safe to say that typical workplace activities in technical communication rarely include the “single-authored, original works” that students produce in academia (Reyman, 2008, p. 61). Instead, they commonly engage in writing activities that include using boilerplates and templates, single sourcing, and repurposing content (Reyman, 2008). Louch (2016) agrees that in technical writing, writers “reuse, remix, and remarket” content, creating based on already-existing works (p. 27). More recently, Lanier’s (2018) research on workplace issues for technical communicators corroborated the common workplace activities enumerated by both Reyman and Louch. The collaborative nature of workplace communication contradicts academia’s requirement that every student needs to do their own work.

Common workplace tasks, such as reusing content, do not abide by what students’ academic careers have taught them about avoiding plagiarism and copyright infringement. The concepts of authorship and textual ownership are vastly different in the workplace and academia (Reyman, 2011; Stillman-Webb, 2017). The repurposing of content is in “direct contradiction of [the students’] academic training” (Louch, 2016). Zemliansky and Zimmerman (2014) acknowledge the disconnect and argue that the academic practices of text ownership need to be reconciled with professional practices to prepare students for “the complex realities of working in a globalized world” (p. 163). Rife (2010) suggests that “educational institutions may want to work harder to help students understand the ways in which paradigms of authorship differ between workplace and educational cultures, or in international contexts” (p. 63).

Even the ethical principles statement for the Society for Technical Communication states, “Before using another person’s work, we obtain permission” (STC, 2018b). However, obtaining permission and attributing authorship is not always required in the workplace, depending upon the circumstances. But what are these settings? Do the textbooks teach which situations do not require permission?

If the purpose of a technical communication education is to prepare students for the reality of the workplace, students need to be exposed to the intricacies of copyright and plagiarism and how both apply to typical workplace activities and practices such as those enumerated by Lanier (2018), Louch (2016), Reyman (2008), and Stillman-Webb (2017). Therefore, textbooks for introductory technical communication courses should adequately describe copyright and plagiarism and general expectations in terms of the workplace as well as the classroom.

One of the undergraduate/graduate-level courses I currently teach in the technical writing and communication department is a course that focuses solely on intellectual property and copyright in technical and professional communication. Obviously, this level of detail cannot be included in introductory textbooks; however, there should be some instruction on plagiarism, authorship, copyright, and textual ownership as they are incorporated in both academia and as standard industry practices. This instruction will better prepare students for the workplace, ensuring that what they produce is both ethical and legal. Students majoring in communication, technical communication, or writing would naturally develop a more complex understanding of the field of intellectual property in advanced courses.

CHANGING COMMUNICATION IN WORKPLACE ACTIVITIES

From my previous experience with introductory technical communication textbooks, instruction includes little more than plagiarism avoidance (cite your sources) as well as copyright infringement avoidance (do not copy others’ work). Except for perhaps a cursory paragraph on work for hire and ethics in the profession (Reyman & Lay Schuster, 2010), the nuanced legal intricacies of authorship, collaboration, and content reuse as they exist in the workplace have not been incorporated. However, new editions of technical communication textbooks should, in theory, include discussions of copying and plagiarism in the context of common workplace activities. But do they? This research then seeks to answer these questions:

- How do the latest editions of widely used technical communication textbooks in the United States teach students about plagiarism, collaboration/authorship, copyright, and ethics?

- How do the approaches used in textbooks align with workplace practices?

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Textbooks and Their Role in Education in Technical Communication

Harwood (2017) noted, in many courses, “The [text]book functions as a de facto syllabus” (p. 264). This means the content in the textbook often dictates what will be addressed throughout the course (Matveeva, 2007; Wolfe, 2009). A textbook analysis, however, “can provide only a partial picture of classroom reality,” and faculty could indeed supplement textbook content with their professional knowledge and other materials (Matsuda & Matsuda, 2011, p. 173–174).

Many faculty, especially adjunct and other contingent faculty, because of the strain of high teaching loads, lack of support, and lack of preparation time (AAUP, 2010, 2018), rely on the textbook for the course structure. In interviews with program administrators, Zarlengo (2019) concluded that faculty “rely heavily on textbooks to shape their service courses” (p. 126).

Contingent faculty (non-tenure track, adjuncts, graduate assistants) teach the majority of classes in higher education (AAUP, 2010, 2018) and are assigned primarily to introductory courses (Morreale, Myers, Backlund, & Simonds, 2016; Reichard, 2003) or service courses (Kimball, 2017; Zarlengo, 2019). Overall, contingent faculty teach most of the technical communication courses (Read & Michaud, 2018), including 83 percent of the service classes in technical communication (Meloncon & England, 2011). Thus, it is probable that contingent faculty, especially adjunct faculty, rely on the textbook to guide course content. Therefore, the content of the textbook should include an adequate explanation of copyright and plagiarism both in academia and in the workplace.

How Avoidance of Plagiarism and Copyright Infringement is Currently Taught in Technical Communication

The emphasis on plagiarism and copyright infringement in academia is generally on exposing plagiarists (Reyman, 2013). While there is often a chapter/section in technical communication textbooks on ethics, the emphasis is often on product liability and safety; a cursory mention of copyright and perhaps a sentence or two about plagiarism may also be included. Textbooks send the message that copying any text from a source created by someone else is strongly discouraged even when/if fair use guidelines are applicable. Additionally, both plagiarism and copyright are presented in an American context only with no consideration of how it connects to the global workplace and economy.

This approach is justifiable when students are writing academic papers in the university. Indeed, appropriately citing sources is expected in academia. Students are required to incorporate others’ work into their own under specific fair use conditions.

However, in the workplace, there are many more contextual details that must be considered when determining the legality and ethics of copying. Universities prepare students to enter the workplace, and the course textbook should support this role.

Workplace Practices that Run Counter to Current Teaching Practices

“Single-authored, original works” are rarely produced in a technical communication workplace (Reyman, 2008, p. 61), and most works are authored by many (Lanier, 2018; Louch, 2016; Zemliansky & Zimmerman, 2014). Indeed “new delivery mechanisms and development tools have changed what [technical communicators] do and how [technical communicators] work” (Stevens, 2018). In 2001, Burnett pointed out that 75–85 percent of writing in the workplace is collaborative, and more recently Bremner (2018) stated that collaborative writing is “highly pervasive” (p. 57). Single authored works are becoming a rarity in the workplace.

As an example, more than a decade ago, researchers noted that single sourcing was important for technical communicators to know (Eble, 2003; Williams, 2003). Evans (2013) explains that single sourcing affects how information is developed in the workplace. The content (what is being communicated) and the format (how it is being communicated) are separated. Content is not conceived of as an entire document, but rather, parts of the document that may be written by different people at different times in different hemispheres. These contents reside in a component content management system (CCM) that provides the structure for individual modules of information to be quickly accessed when needed. Costs are reduced when content is reused instead of being rewritten. The writer assembles components written by other writers, perhaps adds some of his/her own textual content, and then provides the communication in the format required. This internal process does not require the original writer’s approval to use the previously authored content because the owner of the copyright for that work was the employing corporation. Obviously, content authored outside of the organization requires permissions in the form of a copyright release if fair use (discussed later) cannot be substantiated.

Increasing globalization means that the workplace, and thus the products developed by writers as well as the writing incorporated within, are often destined for an international audience. Therefore, technical communication textbooks need to show students how notions of “copying” and ownership are culturally dependent (Reyman, 2008) and that “culture-based norms of collaboration” affect ownership of text (Zemliansky & Zimmerman, 2014). And though there has been significant harmonization among intellectual property rights in countries worldwide, there are still substantial differences in law that affect workplace processes such as reuse. Writers in multinational corporations should understand that the law may be different in different countries. Textbooks should acknowledge this so that students are prepared for the workplace.

Other workplace practices common in technical communication also affect the authorship and copyright ownership of communication products. Configuration of development tools and changes in organizational structures challenge the notion of single-authored products (Stevens, 2018). Documentation as code (docs to code), Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), and Darwin Information Typing Architecture (DITA) have changed workflows and the types of communication consumed and created in the workplace. Customer-specific configurations may reuse or duplicate documentation used for other customers (Parson, 2019). Video is also becoming more common as an end-product. Certainly, the open-source movement affects the ownership of works created using open-source software. And finally, technical communication includes social documentation, the practice of incorporating user-developed content into documentation for a specific technological program (Gentle, 2012). Textbooks should adequately explain how these practices affect copyright ownership and how to avoid infringement and plagiarism.

Although it is not practical for an introductory textbook to elaborate on all these practices, the textbook should provide students with a general understanding that workplace activities will incorporate work written by others in a manner very different than academia.

Proposed Approaches to Avoiding Plagiarism and Copyright Infringement for Technical Communication

To properly educate students who will soon become workplace writers, textbook content must include an overview of plagiarism, collaboration/authorship, copyright law (including fair use), and the ethics of these. However, because these concepts are often context-sensitive, they need to be studied within the context of typical workplace scenarios, and these scenarios should consider the probable differences when multinational corporations are involved.

The textbooks need to explain how “. . . authorship functions differently. . . in the workplace” (Stillman-Webb, 2017, p. 293). This instruction should include an explanation of copyright in work for hire, corporate authorship, and fair use, providing a “more nuanced view of textual ownership” (Reyman, 2008, p. 64).

Moore (2007) believes that discussion should center around the contextual nuances of case studies. Similarly, Stillman-Webb (2017) stresses that “workplace laws, policies, debates, and case studies” must be emphasized in conjunction with academic discussions of copyright and plagiarism avoidance (p. 299).

Students enter college without a strong foundational knowledge of plagiarism and copyright infringement as they relate to academia (Murray, Henslee, & Ludlow, 2016; Myers, 2017; Rodriguez, Greer, & Shipman, 2014). In fact, Henschel (2010) found that students were “surprised and a little fearful” that content reuse in any form was sanctioned by the faculty (p. 243). And according to Rife (2010), this confusion seems to continue into the workplace as professional writers “do not feel they have been properly educated in their writing programs. . .with respect to legal implications for. . .organizational/corporate authorship, and collaborative or joint authorship” (p. 62).

So, what do students currently learn in textbooks for introductory technical communication classes?

METHODOLOGY

Sample Selection

A search for “technical communication” on Amazon.com yielded hundreds of books. Selection criteria were used to narrow the sample to textbooks frequently used in introductory technical communication courses. Selection criteria specified the words “technical communication” or “technical writing” had to be in the book title. However, titles that specified an industry (i.e., engineering, medical, etc.), specified a narrow focus (i.e., Readings in. . .), or were not published in the United States were eliminated because this study focuses only on broad surveys of the field of technical communication.

The first 100 books from the Amazon.com search were considered for the survey and down-selected to the eight used in the study. Identifying the texts most often used in academia revealed many were outdated with a copyright/publication date older than 2017. Because this research seeks to influence current instruction on intellectual property in the field, textbooks selected had to have a copyright date of 2017 or newer. Before these older texts were eliminated from the sample, a search of the publisher’s website was conducted to determine if an updated edition was available. Additionally, because best-selling textbooks are generally those that have been used in academia for a length of time, only books with a third edition or higher were included in the sample. As suggested by Matsuda and Matsuda (2011), handbooks, brief textbooks, and reference books were eliminated from consideration.

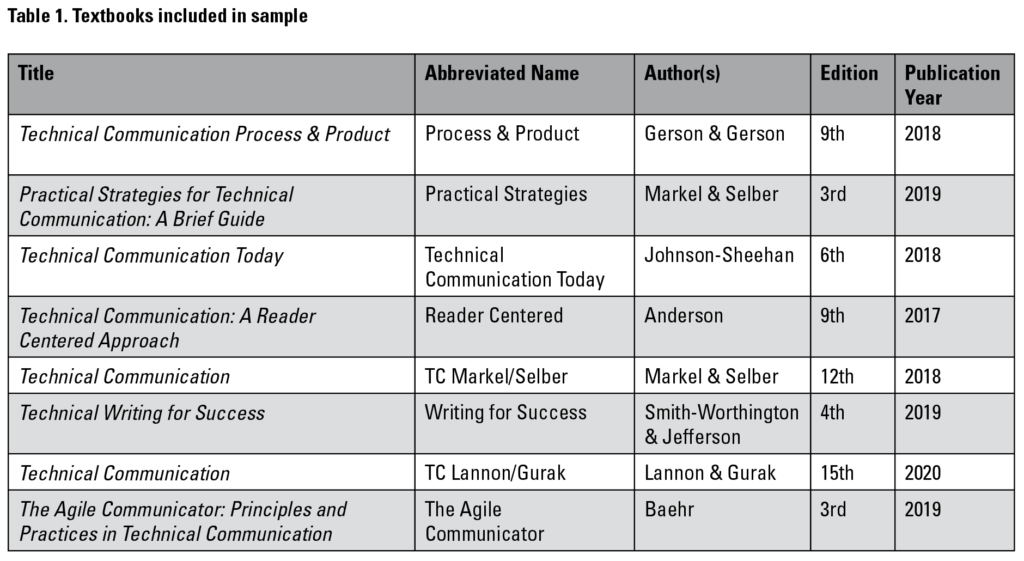

Many textbooks, however, are not available through Amazon.com. So, websites for the major textbook publishers in the field—Cengage, Pearson, Macmillan, Routledge—were searched using the stated criteria. As a result, several additional texts were added to the sample. Open-source books were not considered for this study. See Table 1 for a list of textbooks included in the sample. Note that the books were reviewed in print format except for The Agile Communicator. None of the ancillary materials for the texts were examined as contingent faculty often do not know they should request them or do not have the time as the course start date is imminent.

Data Collection and Analysis – Phase 1

This content analysis studies textbook depictions of plagiarism, collaboration-authorship, copyright, and ethics in technical communication.

Matsuda and Matsuda’s (2011) first phase analysis method was modified slightly for use in examining the textbooks. The table of contents and index as well as the actual text from chapter content were examined for any representations of plagiarism, collaboration/authorship, copyright, and ethics. These depictions were classified by their location in the text: chapter, section, box, or graphic. As the data collection began, it became obvious that the terms “teams,” “teaming,” and “teamwork” were often used to describe collaboration, so these terms were used interchangeably with “collaboration” in this data collection.

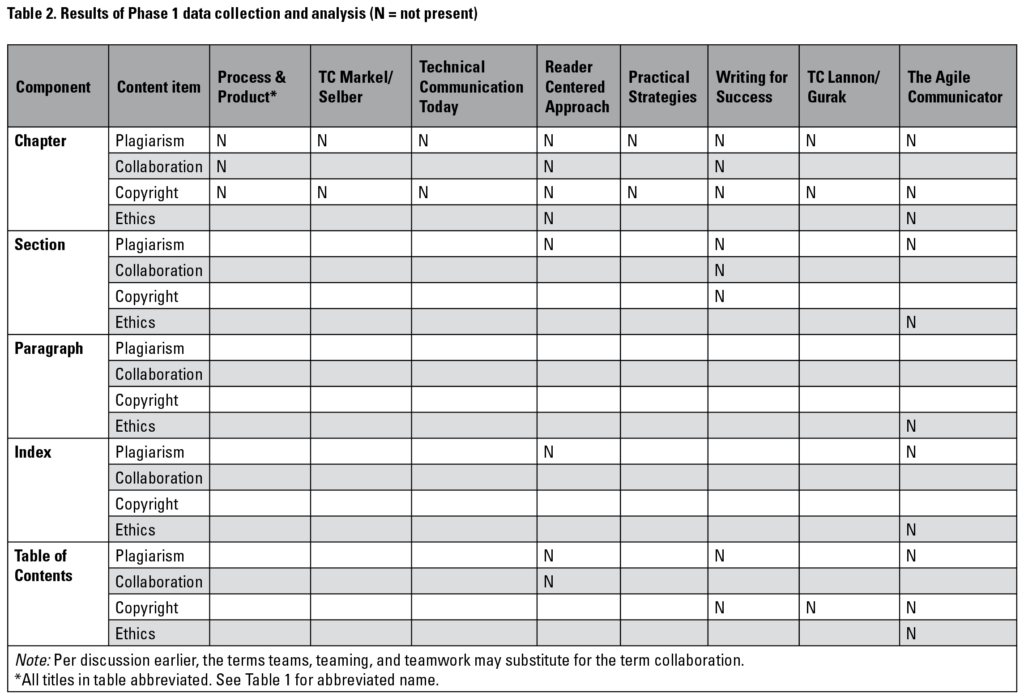

Table 2 illustrates the distribution of the plagiarism/ collaboration-authorship/copyright/ethics features in the sample textbooks.

As expected, the majority (75 percent) of the texts included a chapter on ethics, although the contents of the chapters varied as discussed later. Five (62.5 percent) of the texts focused on collaboration (teams/teaming/teamwork) as a separate chapter. None of the texts included an entire chapter on plagiarism or copyright.

Each text’s chapters were further subdivided into sections. A heading of some type began each “section,” and there was a two-paragraph minimum to be considered a section (rather than a paragraph). Further, it was assumed that textbooks would have a section on a topic if an entire chapter was devoted to the topic. Three of the texts did not include even a full section on plagiarism, and one did not provide a section on copyright or collaboration.

Within each section, each paragraph was scrutinized to determine if the topics of plagiarism, collaboration, copyright, and ethics were included. Not surprisingly, all but one of the textbooks included at least a cursory look at the topics under study (except for The Agile Communicator, which did not include any paragraphs about ethics).

Within each section, each paragraph was scrutinized to determine if the topics of plagiarism, collaboration, copyright, and ethics were included. Not surprisingly, all but one of the textbooks included at least a cursory look at the topics under study (except for The Agile Communicator, which did not include any paragraphs about ethics).

The table of contents and the index were the two sections that contained the smallest unit of measurement for a topic to be considered “present.” Accordingly, these two sections were searched for the following keywords: plagiarism, collaboration, copyright, and ethics. The indices of all the texts contained the keywords in some manner except for Reader-Centered Approach (the keyword “plagiarism”) and The Agile Communicator (the keywords “plagiarism” and “ethics”). Not all the texts include the same level of detail in the table of contents. The Agile Communicator only lists broad topics, Technical Writing for Success adds subtopics, and the rest provide a detailed level of granularity on each chapter’s contents.

Data Collection and Analysis – Phase 2

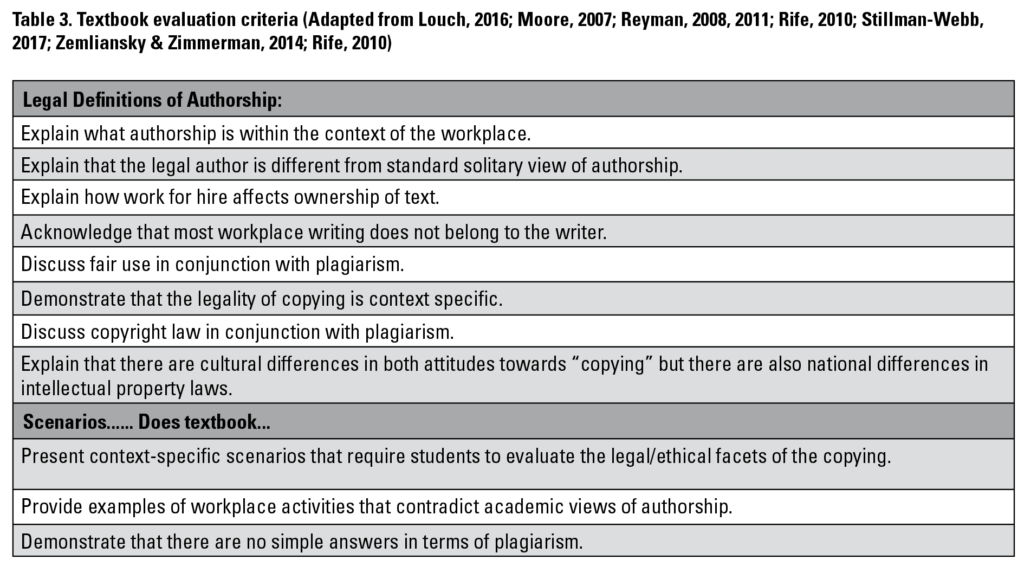

A qualitative content analysis was then conducted. A rating scale was developed using researchers’ recommendations for teaching plagiarism and copyright infringement in technical communication (see Table 3; Louch, 2016; Moore, 2007; Reyman, 2008, 2011, 2013; Rife, 2010; Stillman-Webb, 2017).

Each textbook was rated on the extent to which it fulfills each of the 10 criteria using a 0–3 Likert scale, with 0 indicating the text does not fulfill the criteria at all and 3 indicating the text fulfills the criteria.

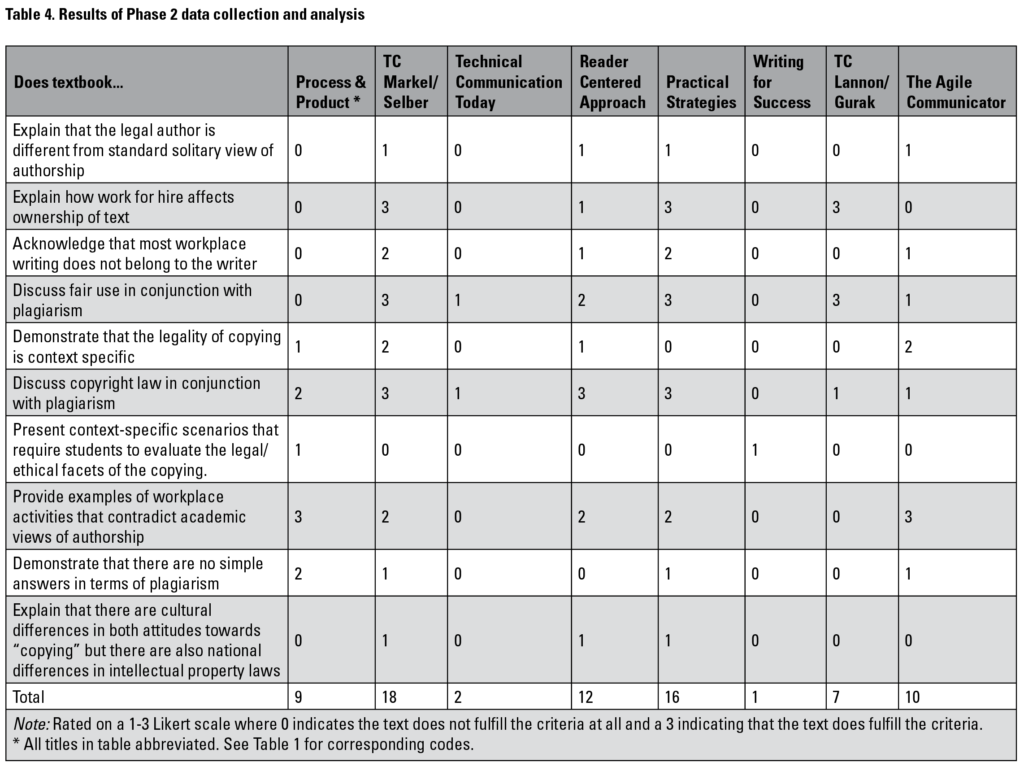

The sum of each title’s scores was computed. Only three of the texts scored more than 10 (on a scale of 30). These were both texts authored by Markel and Selber (2019, 2018), Practical Strategies for Technical Communication and Technical Communication as well as Anderson’s (2017) Technical Communication: A Reader-Centered Approach. Each criterion is discussed in detail in the Results section with a close examination of the highest-scoring texts (see Table 4).

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

The rating scale presented in Table 3 was developed from researchers’ suggestions on how avoidance of plagiarism and copyright infringement should be taught. These were enumerated in the “Proposed Approaches” section. The textbook samples were scrutinized to determine how each presented the content suggested or included the scenarios proposed.

Legal Definitions of Authorship, Work for Hire, and Ownership

An explanation of legal authorship should begin by explaining the traditional view of an author, namely that the person who creates something is the copyright owner. It should then differentiate between creating work and owning the copyright to the work. The text should clearly explain how authorship differs from ownership and how collaboration among writers affects copyright ownership.

Markel and Selber (2018, 2019) specifically ask the reader why the creator of a work would not be the owner of the copyright before explaining the reasoning: “The answer lies in a legal concept known as work for hire. Anything written or revised by an employee on the job is the company’s property, not the employee’s” (2018, p. 24; 2019, p. 22). However, only Lannon and Gurak (2020) provide further explanation of work for hire and copyright ownership by addressing non-employees who create content: “Contract employees may be asked to sign over the copyright to materials they produce on the job” (p. 143). Both of the Markel and Selber texts (2018, 2019) indicate that employees would generally not own the rights to the work they create; however, they do not go a step further and state that most of the works an employee creates are owned by the employer.

Cultural attitudes and national differences in law

Although most of the texts tackled the topics of intercultural communication and attitude differences, few explained that intellectual property laws as well as a culture’s attitudes towards “copying” were important considerations in workplace writing. Anderson (2017) states only that “ethical standards for citing sources differ from culture to culture. . .” and the ones that are listed in the text only “apply in the United States, Canada, and Europe” (p. 84). However, there are variations in copyright law even between neighboring countries, and this is not explicitly stated by Anderson, although both texts by Markel and Selber (2019, 2020) write that “exporting goods to countries with different laws is a. . .complex topic” (p. 28, 37). While it is not expected that the texts would go into any detailed explanations of the differences between countries, students would benefit from a general warning that there are differences and a specific example. This is unfortunate given the global reach of major corporations, many of which have a physical presence on several continents.

Copyright law vs. plagiarism

Since copyright and plagiarism are often confusing to students, a solid explanation of how the two are connected is in order. Copyright governs the right to copy something that is another’s intellectual property. If a person copies a movie without getting permission from the copyright owner, it constitutes copyright infringement similar to software piracy and is a criminal law offense. If a person copies quotes from a text to support their assertions and does not attribute the source, this is plagiarism. However, a copyright owner’s rights are not absolute, and small portions of text may be reproduced under the fair use exemption (explained later).

Markel and Selber (2018, 2019) provide this clarification by building on what students know, the concept of plagiarism. They explain that plagiarizing is an ethical issue, one that could get a person fired from a job or expelled from school, but the person would not be “fined or sent to prison” (2018, p. 24; 2019, p. 21). They continue by explaining that copyright, however, is a legal issue that could result in fines or imprisonment (Markel & Selber, 2018, 2019).

While Gerson and Gerson (2018) also discuss plagiarism in conjunction with copyright infringement, their explanation leads a student to believe that avoiding copyright infringement is as easy as citing your sources. In a section headed “Copyright Laws,” the authors explain that “Taking words and ideas without attributing your source through a footnote or parenthetical citation is wrong. You should respect copyright laws” (Gerson & Gerson, 2018, p. 128). This statement seems to imply that a person can avoid copyright infringement merely by attributing the source, which is not true—a clearer explanation of when and how attribution matters is needed.

Fair use and plagiarism

Texts should include an elaboration of §107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. This includes the uses that favor fair use (i.e., teaching, research, criticism, etc.) as well as listing the four fair use factors and describing how they are applied. These factors are:

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The discussion of these factors and their applications should help students avoid plagiarism and copyright infringement. However, none of the texts discuss all these applications.

In “Chapter 4 Weighing the Ethical Issues,” Lannon and Gurak (2020) present information about legal issues and plagiarism, indicating that readers should “Know the limitations of legal guidelines and avoid plagiarism” (p. 69). Then three chapters later, in the section “Frequently Asked Questions about Copyright,” they list the four fair use factors contained in the United States Code. Lannon and Gurak go on to say that “Courts differ on when and how to apply the four fair use questions, especially in cases related to digital media and material used from the internet” but provide no examples (p. 142).

Baehr (2019) provides no explanation of the meaning of fair use within the text; however, one of the end-of-chapter assignments is to research fair use and how it is implemented in both academic and workplace writing. If students are not assigned that question, though, they would not understand how fair use applies to their work. Additionally, the text incorrectly states that “Fair use laws generally permit the use of 250 words from a single-source, with citation” (p. 67). However, the government’s information about fair use acknowledges that there is no set number of words that are allowable (United States Copyright Office, 2019).

Markel and Selber (2018, 2019), as well as Lannon and Gurak (2020), correctly explain that in determining fair use, the amount copied must always be considered in terms of its substantiality to the whole. Johnson-Sheehan (2018) indicates that “especially if you are a student,” copying with attribution may be considered fair use (p. 92). Johnson-Sheehan (2018) explains that uses for the purposes of “criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching…scholarship, or research” (Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U. S. C. § 107) are more favorable to fair use and states that “if your use of materials falls under these guidelines, you may have a limited right to use the materials without asking permission” (Johnson-Sheehan, 2018, p. 92) but does not explain the limitations on fair use nor list the four fair use factors.

Summary of texts’ handling of ownership issues

None of the texts completely address the criteria in Table 3 (although both texts by Markel and Selber [2018, 2019] provide limited coverage of these criteria). Most of the texts, however, are deficient in presenting how legal ownership of content differs from traditional authorship. Of the non-Markel/Selber texts, only the Lannon and Gurak (2020) text presents a clear and complete explanation of work for hire and its relationship to the work of a technical communicator. Likewise, most of the texts do not provide a clear discussion of the distinctions between copyright infringement and plagiarism. All but two of the texts include some presentation of “fair use” and the factors associated with it.

Context-Specific Scenarios

Moore (2007), Reyman (2008), and Stillman-Webb (2017) all proposed using specific scenarios so that students can apply the information they learned about authorship, fair use, and copyright. Reyman (2008) explains that scenarios demonstrate to students that a determination of plagiarism or copyright infringement cannot be determined by a “black-and-white approach” (p. 66). Reyman (2008) suggests that scenarios characterize plagiarism as more complex and context-sensitive than the all-too-present “do not steal” mandate (p. 66).

Most of the texts included a few scenarios for students to practice applying the law and ethics to a specific situation. These cases did not focus on copying, copyright, or plagiarism, except for two texts (Smith-Worthington and Jefferson and Gerson and Gerson) that included simple scenarios requiring students to evaluate the legal/ethical facets of copying material created by others. These scenarios, however, were simplistic and could easily be answered through a Google search and a routine application of copyright law. It is important to note that the ancillary materials, teachers’ guides, supplements, etc., for each of the texts (if available) may indeed include in-depth scenarios for students to evaluate, but for this research, only the student textbooks were reviewed.

None of the texts includes an in-depth case involving copyright or plagiarism similar to two of the nine role-playing scenarios included in Ethics in Technical Communication: Shades of Gray (Allen & Voss, 1997). Even cases, such as the two paragraph-long scenarios Reyman (2011) suggests as examples of the “perplexing circumstances” that the workplace presents (p. 349), were not included in the texts. A goal is for students to wrestle with the complexities of authorship, legal doctrine, and ethics, and not necessarily “solve” the cases (Reyman, 2011, p. 364). It is through this struggle that students understand that copyright in the workplace is highly nuanced.

Workplace activities that contradict academic views of authorship

Five of the texts included information about reuse, single sourcing, templates, or boilerplate (standardized text) materials as common workplace activities. Anderson (2017) indicates that in the workplace, a writer often builds his or her work on the work of other employees within their company, and this is perfectly acceptable—which, of course, runs counter to the traditional academic view of reuse. Markel and Selber (in both texts) explain that in business, “the reuse of information is routine because it helps ensure that the information a company distributes is both consistent and accurate” (2018, p. 24; 2019, p. 21). Two pages later, that they provide examples of acceptable reuses of information.

The Agile Communicator includes a range of workplace activities involving content reuse. In Chapter 3, Baehr (2019) discusses legacy documents, explaining that they are “existing content sources [that may be]. . . external (sources outside of an organization) or internal (sources within an organization)” (p. 56). Baehr (2019) points out considerations that need to be made when using such material but refers the reader to a section four pages later, rather than addressing these considerations in the immediate context. Baehr also discusses single-sourcing and how the content an organization “owns” can be freely used or adapted to develop other company content while emphasizing that reuse of content external to the organization requires citation as a minimum and perhaps a copyright release.

Gerson and Gerson (2018) discuss both boilerplate information and single-sourcing, although the consequences of single-sourcing on copyright and plagiarism are not discussed.

Boilerplate content is also mentioned by Markel and Selber (in both texts), who warn students not to include excessive amounts of another person’s writing unless “it is your company’s own boilerplate” (2018, p. 26; 2019, p. 23). Unfortunately, they do not explain what boilerplate is, there is no glossary in the back of the book, and the index does not include the word. Not until readers arrive at the next section, the “Ethics Note,” do they learn that boilerplate is a text that is repurposed within a company (e.g., a company profile or product description) so that it does not have to be rewritten every time it is used, saving costs in document production.

No simple answers

Due to the brevity of each textbook’s treatment of the topics, the complexity of plagiarism and copyright laws was not fully apparent. However, Gerson and Gerson (2018) did specifically state, “avoiding intellectual property theft and plagiarism in the workplace is not always clear cut” (p. 129). Had these texts included scenarios that required students to reason the ethics and legalities of the situation, the complications of plagiarism and copyright would, no doubt, be amply illustrated by the specifics of each situation.

CONCLUSION

I initially included the terms “collaboration,” “teams,” and “teaming” for the first-phase data collection and analysis because I anticipated that workplace activities such as single sourcing and content reuse would be discussed within the context of collaboration. That was largely not the case. Most textbooks that discussed single sourcing, reuse, or boilerplate text included it within the context of intellectual property or plagiarism (e.g., Gerson and Gerson, 2018, and Markel and Selber, 2018, 2019). However, some instances of treatment of these topics occurred in unexpected contexts, such as The Agile Communicator’s discussion of boilerplate materials in the context of conducting research (Baehr, 2019).

The textbooks did, however, include some discussion of collaborative writing, such as Gerson and Gerson’s (2018) excellent coverage of the use of wikis and Google Docs as team writing tools. However, when discussing principles of collaboration, all but one of the texts were more likely to situate the collaboration into a generic setting without explaining single-sourcing and content reuse. Baehr (2019) did, however, frequently discuss collaborative authoring and reuse as they are practiced in the workplace.

Students enroll in college courses and programs to gain expertise for the workplace. Unfortunately, in many instances, there is a significant disconnect between what students learn and how this learning applies in the workplace. Traditional views of authorship and academia’s emphasis on “not copying” to avoid plagiarism run counter to industry practices in the workplace. Textbooks should prepare students to understand the important differences of copyright, plagiarism, and ownership as they pertain to both academia and the workplace. This content analysis found that the extent to which currently used textbooks accomplish these goals is generally grossly deficient.

Reyman (2008) believes it is important for students to understand the inherent complexity of applying copyright law and plagiarism to workplace practices, asserting that this can best be achieved by using realistic teaching scenarios. Not only were most of the texts deficient in the instruction in key concepts, such as fair use and work for hire, but the texts also did not force the reader to grapple with the messiness of workplace scenarios.

Additionally, because of the varying structural organization of the textbooks, information on topics such as plagiarism, ownership, authorship, and copyright was often fragmented (split among several sections in different chapters). Further, the texts did not explore the nuances of copyright and plagiarism in the workplace.

Teaching plagiarism and copyright infringement avoidance by comparing the two in academia (which is the realm with which students are familiar) and then in technical communication has not been incorporated into introductory technical communication textbooks. This is unfortunate given the increasing intricacies of copyright and plagiarism introduced by workplace practices. Students entering the workplace need the skills to deal with these complexities. However, of the texts reviewed, only the texts by Markel and Selber provide instruction that partially fulfills the criteria proposed by researchers (Table 3 and 4). Likewise, integration of plagiarism and copyright scenarios focused on workplace issues is absent from all but one of the texts. Workplace activities such as single sourcing, legacy documentation, document ecologies, and content reuse are briefly mentioned in a few of them, with only Baehr frequently providing an explanation of these processes in the context of the workplace.

More than a decade ago, Reyman (2008) proposed dialogue between workplace practitioners and academia as vital to fully prepare students for the workplace. What workplace activities involve issues of copyright and plagiarism? How are these issues resolved? Further research is needed to survey practitioners in the workplace to find these answers and incorporate the information into future textbooks.

REFERENCES

Allen, L., & Voss, D. (1997). Ethics in technical communication: Shades of gray. New York, NY: Wiley & Sons.

American Association of University Professors (AAUP). (2010). Teaching and teaching-intensive appointments. Retrieved from http://www.aaup.org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/AAUP/comm/rep/teachertenure.htm?PF=1

American Association for University Professors. (2018, October). Data snapshot: Contingent faculty in US higher ed. AAUP Updates. Retrieved from https://www.aaup.org/news/data-snapshot-contingent-faculty-us-higher-ed#.W8VOm2hKhPZ

Auman, H. S. (2014). How well do technical communication students understand copyright explanations in common technical communication textbooks? (Master’s thesis, Missouri State University).

Bremner, S. (2018). Workplace writing: Beyond the text. New York, NY: Routledge.

Burnett, R. (2001). Technical communication. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace.

Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSSI). (2019a). English language arts standards-Writing-grade 4. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/W/4/8/

Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSSI). (2019b). Standards in your state. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/standards-in-your-state/

Common Sense. (2018). Whose is it, anyway? (3-5). Retrieved from https://www.commonsense.org/education/lesson/whose-is-it-anyway-3-5

Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U. S. C. § 107

Eble, M. F. (2003). Content vs. product: The effects of single sourcing on the teaching of technical communication. Journal of the Society for Technical Communication, 50(3), 344–349.

Evans, R. (2013). Teaching single sourcing to bridge the gap between classrooms and industry. TechCom Manager, September.

Gentle, A. (2012). Conversation and community: The social web for documentation. Laguna Hills, CA: XML Press.

Harwoood, N. (2017). What can we learn from mainstream education textbook research? RELC Journal, 48(2), 264–277.

Henschel, S. M. (2010). Authoring content for reuse: A study of methods and strategies, past and present, and current implementation in the technical communication curriculum (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Texas Tech University http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.875.5148&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Kimball, M. A. (2017). The golden age of technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 47(3), 330-358. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0047281616641927

Lanier, C. R. (2018). Toward understanding important workplace issues for technical communicators. Technical Communication, 65(1), 66–84.

Louch, M. O. (2016). Single sourcing, boilerplates, and re-purposing: Plagiarism and technical writing. Information Systems Education Journal, 14(2) 27–33.

Marshall, S., & Garry, M. (2005). How well do students really understand plagiarism. In Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education, 2005 https://ascilite.org/conferences/brisbane05/blogs/proceedings/52_Marshall.pdf

Matsuda, A., & Matsuda, P. K. (2011). Globalizing writing studies: the case of U.S. technical communication textbooks. Written Communication, 28(2), 172-192.

Matveeva, N. (2007). The intercultural component in textbooks for teaching a service technical writing course. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 37(2), 151-166.

Meloncon, L., & England, P. (2011). The current status of contingent faculty in technical and professional communication. College English, 73(4), 396-408.

Moore, M. R. (2007). Copyright law and a fair use pedagogy: Teaching and learning strategies for technical communication courses). In C. L. Selfe (Ed.), Resources in technical communication: Outcomes and approaches (pp. 95-110). New York, NY: Routledge.

Morreale, S. P., Myers, S. A., Backlund, P. M., & Simonds, C. J. (2016). Study IX of the basic communication course at two- and four-year U.S. Colleges and universities: A re-examination of our discipline’s “front porch”. Communication Education, 65, 338–355. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2015.1073339

Murray, S. L., Henslee, A. M., & Ludlow, D. (2016). Evaluating engineering students’ understanding of plagiarism. Quality Approaches in Higher Education, 7(1), 5–11.

Myers, C. S. (2017). Plagiarism and copyright: best practices for classroom education. College and Undergraduate Libraries, 25(1), 91–99.

Parson, U. (2019). The challenges of digitalization in technical communication. Retrieved from https://www.parson-europe.com/en/knowledge-base/563-digitization-technical-communication.html

Read, S., & Michaud, M. (2018). Who teaches technical and professional communication service courses?: Survey results and case studies from a national study of instructors from all Carnegie institutional types. Programmatic Perspectives, 10(1), 77–109.

Reichard, G. W. (2003). The choices before us: An administrator’s perspective on faculty staffing and student learning in general education courses. New Directions in Higher Education, 123, 61–69.

Reyman, J. (2008). Rethinking plagiarism for technical communication. Technical Communication, 55(1), 61–67.

Reyman, J. (2011). The role of authorship in the practice and teaching of technical communication. In M. C. Rife, S. Slattery, and D. N. DeVoss (Eds.), Copy(write) Intellectual property in the writing classroom (pp. 347–367). Anderson, SC: Parlor Press.

Reyman, J. (2013). Plagiarism vs. copyright law: Is all copying theft. In M. Donnelly, R. Ingalls, T. A. Morse, J. Castner Post, & A. M. Stockdell-Giesler (Eds), Critical conversations about plagiarism (pp. 22-35). Anderson, SC: Parlor Press.

Reyman, J., & Lay Shuster, M. (2010). Guest editors’ introduction: Technical communication and the law. Technical Communication Quarterly, 20(1), 1-4.

Rife, M. C. (2010). Copyright law as mediational means: Report on a mixed methods study of U.S. professional writers. Technical Communication, 57(1), 44-67.

Rife, M. C. (2013). Invention, copyright, and digital writing. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University.

Rodriguez, J. E., Greer, K., & Shipman, B. (2014). Copyright and you: Copyright instruction for college students in the digital age. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(2014), 486-491.

Society for Technical Communication (STC (2018a). Defining technical communication. Retrieved from https://www.stc.org/about-stc/defining-technical-communication/

Society for Technical Communication (STC). (2018b). Ethical principles. Retrieved from https://www.stc.org/about-stc/ethical-principles/

Stevens, D. (2018). You are here: Mapping technical communication trends against best practices. Intercom. Retrieved from https://www.stc.org/intercom/2018/04/you-are-here-mapping-technical-communication-trends-against-best-practices/

Stillman-Webb, N. (2017). “Keeping it “real”: Contextualizing intellectual property and privacy in the online technical communication course. In. K. C. Cook, & K. Grant-Davie, Online education 2.0: Evolving, adapting, and reinventing online technical communication (pp. 289–302.

United States Copyright Office. (2019). More information on fair use. Retrieved from https://www.copyright.gov/fair-use/more-info.html

Williams, J. D. (2003). The implications of single sourcing for technical communicators. Technical Communication, 50(3), 321–327.

Wolfe, J. (2009). How technical communication textbooks fail engineering students. Technical Communication Quarterly, 18(4), 351–375. http://dx.doi.org/10.10.1080/10572250903149662\

Zarlengo, T. P. (2019). No one wants to read what you write: A contextualized analysis of service course assignment (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Proquest Dissertations and Theses. (13904425)

Zemliansky, P. & Zimmerman, T. A. (2014). Workplace realities versus romantic views of authorship: Intellectual property issues, globalization, and technical communication. In K. St.Amant, & M. C. Rife (Eds.), Legal issues in global contexts: Perspectives on technical communication in an international age. New York, NY: Baywood Publishing Company.

APPENDIX: Complete Bibliographic Information for Textbooks in Sample

Anderson, P. V. (2017). Technical communication: A reader centered approach (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage.

Baehr, C. (2019). The agile communicator: Principles and practices in technical communication (3rd ed.). Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing.

Gerson, S. J., & Gerson, S. M. (2018). Technical communication process & product (9th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson.

Johnson-Sheehan, R. (2018). Technical communication today (6th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson.

Lannon, J. M., & Gurak, L. J. (2020). Technical communication (15th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson.

Markel, M., & Selber, S. A. (2018). Technical communication (12th ed.). New York, NY: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Markel, M., & Selber, S. A. (2019). Practical strategies for technical communication: A brief guide (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Smith-Worthington, D., & Jefferson, S. (2019). Technical writing for success (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michele Mosco is an instructor in Technical Writing and Communication at Arizona State University. In addition to copyright and intellectual property, her research interests include data visualization, open educational resources, underrepresentation of women in computer science and information technology, and comics in technical communication. Before joining the university faculty, she worked as an academic librarian. She can be reached at michele.mosco@asu.edu.

Manuscript received 23 September 2019, revised 15 February 2020; accepted 5 June 2020.