By Beth J. Shirley

ABSTRACT

Purpose: This article presents a new rhetorical model for science and technical communication—specifically climate change communication—which the author is calling dissociative framing, in which climate change can be dissociated from the behaviors necessary to mitigate the human contribution to climate change, while positive associations are formed with those behaviors. This model serves as an alternative to the knowledge deficit model still in use in much science communication and is applicable both for students and practitioners of technical communication.

Method: The model was developed by examining Matthew Nisbet’s work on framing in conjunction with Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s work on dissociation. I conducted a coded rhetorical analysis of two fact sheets produced by the Utah State University Extension Office with information on how their audience can change personal behaviors to mitigate their personal impact on climate change. I suggest how a dissociative frame would present the information more effectively.

Results: A dissociative framing model can provide practitioners in technical and professional communication (TPC) a way to work around science skepticism and motivate action, especially when working with short, community-based genres, and can provide teachers of technical communication with a heuristic for instructing students on how to best engage a skeptical audience.

Conclusion: While rural communities in the United States are especially prone to climate skepticism, it is important that they be informed and empowered to make the necessary behavioral changes to mitigate the human impact on climate change. Fact sheets published by extension services provide an excellent opportunity to inform and empower. A dissociative framing model provides a clear way to empower these communities with knowledge of how to mitigate their impact on climate change without diving into the political issues embroiled in climate science.

Keywords: Environmental science communication, rural engagement, framing, dissociation

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Technical communicators can employ a rhetorical model called dissociative framing in which the communicator dissociates an intended action from a notion, political or ideological, that is perceived to be incompatible for that specific audience.

- For example, when communicating about how and why to make certain behavior changes with regard to climate change, such as reducing energy consumption or planting trees, the communicator may choose to avoid discussing climate science altogether. In this way, the communicator can dissociate these behaviors from the perceived-to-be controversial topic and to re-associate the behaviors with values the audience is more likely to view as compatible, such as saving money or building resilient communities.

INTRODUCTION

While the scientific community maintains consensus on climate change as a human-driven, social justice issue (IPCC, 2018), many Americans seem confused or unconvinced by the data that has been presented in nearly every way imaginable (Howe, Mildenberger, Marlon, & Leiserowitz, 2015). This lack of consensus among the public and politicization of the issue has led to a lack of action by governments, corporations, and individuals. Rhetoric of science and technical communication scholars have worked to understand what our role is in this wicked problem (Blythe, Grabill, & Riley, 2008; Cagle & Tillery, 2015; Ceccarelli, 2011; Coppola & Karis, 2000; Druschke, 2014; Druschke & McGreavy, 2016; Herndl, 2014; Herndl & Cutlip, 2013; McGreavy et al., 2016; Palmer & Killingsworth, 1992). When the data is out there, do we need to keep pumping it out in new and more engaging ways, or can there be a more methodical approach? How do we make the science any clearer? How do we work with communities and groups whose identities may be wrapped tightly around issues pitted against environmentalism (e.g., coal mining, timber extraction)? And what can we do to motivate individuals to act on climate change?

With the recent trend of doubt in science and mistrust of science-producing institutions among the general population of the United States (PEW, 2017), the question of how we motivate action on climate change may need to be reexamined or reframed: How important is it to first make the science clear? In an era referred to colloquially as the “Post-Fact” or “Post-Truth” era, when misinformation is almost more readily available than truth, and when there is little time left to act (about ten years as of this writing, according to the latest IPCC reports), we need to convince people to act quickly, not just to accept the science.

Increasing scientific literacy is, of course, important for the long haul. Yet despite the wealth of readily available information already translated for the

public in the forms of daily news articles, websites, government-issued climate reports, and blockbuster documentaries, only 17% of Americans say they are “alarmed” about global warming and say it is a top voting priority, while 10% say they are “dismissive” and tend to oppose all climate action (Roser-Renouf et al., 2016). Many of these methods of environmental communication rely on what is known as the knowledge deficit model, in which the author assumes there is a gap in the audience’s knowledge that must simply be filled before the audience will be willing to take action. But problems with accepting and acting on climate science, and science in general, run deeper than a simple lack of publicly available information, as scientific information becomes embroiled in political debates and tied to specific ideologies.

Even more troubling than the extensive doubt and denial of climate science, however, is the discovery that even those who are concerned about climate change are not likely to alter their behaviors (Hornsey et al., 2016; Kellstedt, Zahran, & Vedlitz, 2008; Lazo, Kinnell, & Fisher, 2000; Rabinovich, Morton, Postmes, & Verplanken, 2012) or even political action (Roser-Renouf et al., 2016). Meanwhile, emboldened by the perceived apathy or dismissal from the public, political entities in the United States continue to roll back regulations designed to mitigate climate change and cut incentives designed to encourage the development of sustainable energy resources (Davenport, 2019; Fears, 2019; Stetch Ferek & Puko, 2019). The problem is not just that the science lacks clarity; the problem is that the threat posed by climate change is conveniently denied or ignored in favor of maintaining our current lifestyles. I contend that 1) technical communicators working in climate change communication can shift their more immediate communication strategies from trying to move people from denial to acceptance toward new methods that motivate people to direct action, and 2) that teachers of technical communication can encourage students to think beyond the knowledge deficit model.

In this article, I present dissociative framing: an approach to technical communication in which the writer distances critical takeaways from contextual information that may be perceived as objectionable or controversial and re-associates the takeaways with acceptable information or outcomes. For example, if an author knows that a given audience is deeply embedded in the coal mining industry, they can more effectively motivate behavioral change regarding the environment by leaving coal mining out of it altogether. We also know that coal mining has been pitted against climate activism in general, and therefore, a dissociated frame that seeks to inform and empower a rural, coal mining community toward energy-reducing behavior would avoid the issue of climate change altogether and would instead work to associate these behaviors with things understood to be of strong value to that specific audience, such as saving money.

Dissociative framing makes a case for people to adopt new behaviors toward mitigating anthropocentric climate change by focusing on reasons other than mitigating climate change for those behaviors and practices. Especially in shorter communication genres, such as the extension fact sheets I discuss in this article, it may be necessary that the audience’s associations with the issue of climate change (or any politicized issue) be assessed and possibly dissociated from the behaviors the author is writing about, while building new associations with ideas and values the audience holds to be positive.

Apparent Contradictions

The term fact sheet may lead to an assumption that these documents are purely informative and therefore should not also be considered persuasive documents. Yet scholarship in the field of technical communication has called for a move away from this binary that may be perceived between informative or persuasive and to instead emphasize that all technical writing is rhetorical and should be considered persuasive, both in practice and in teaching. For example, Joswiak and Duncan (2020) examined best-selling textbooks in the field and found this delineation between informative and persuasive to be a common theme that “contradicts practitioners’ roles as persuasive communicators” (p. 29). Despite this delineation in textbooks, the authors cite scholars going back 30 years agreeing that all communication, even communication that is presented as “informative only,” is persuasive and should be considered as such by the communicator (Bazerman, 1988; Gross, 1996; Keith, 1997; Knoblauch & Brannon, 1984; Kynell, 1994; Ornatowski, 1992; Toulmin, 2003; Tebeaux & Dragga, 2018). Joswiak and Duncan (2020) contend “therefore, it is important to recognize that all writing operates persuasively in either implicit or explicit ways,” and must be treated as such by practitioners and taught as such by instructors (p. 38). This is especially true in a political climate when the facts, themselves, have strong ties to distinct ideologies.

To address this complication with science communication, I present a new rhetorical model: dissociative framing, based on Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s (1969) work on the concept of rhetorical dissociation and Nisbet’s (2009; 2010) work on framing. Framing, Nisbet argues, is often done unconsciously by communicators but is always part of communication as it involves how the writer chooses to arrange and focus information. When done mindfully, framing can be effective at jumping party lines and deeply embedded tribalisms. Dissociation is the splitting of ties between a concept that is undesirable or even hated by a given audience from the concept the author is trying to persuade that audience to accept, forming new associations to replace the old. For example, an advocate for Planned Parenthood may talk to someone who is anti-abortion by framing the conversation around the services the organization provides aside from abortion, such as preventative women’s health care, omitting or downplaying discussion of abortion. While the organization is already closely associated with the practice of abortion, it may still be beneficial to form this new association with women’s health.

Dissociated framing requires a close examination of the audience to first understand what important factors are at play, what sort of industries are important, what values does this community hold, and what frames might be effective at motivating action. Such an examination may reveal useful anomalies. For this article, I will look specifically at rural communities in Central Utah as an example site for examination. Rural here refers to an incorporated area with fewer than 2,500 people (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). These areas tend to have less access to the internet and therefore information (Hale et al., 2010; Salemink et al., 2017; Whitacre & Mills, 2007). In a phenomenon described as the “digital divide,” citizens in these areas often rely on print media made available in the mail or at events, either due to lack of access or resistance to adapting to digital technologies. Rural communities are also often overlooked in research due to “urban bias” (Chambers, 1983), and many researchers are apprehensive or unwilling to work with them because of perceived or real sharp political differences (Walsh, 2013), which compounds the marginalization of these communities. Thus, it is especially important for universities to reach out to serve rural areas. This mission is often directly met through land-grant university extension programs and their engagement events and publications, including what are known as fact sheets, brief, informational documents that provide valuable information on agricultural developments and other technical material, including research done at the university. These fact sheets may often be written using the deficit model, but they are a perfect opportunity for practitioners of technical writing to utilize dissociative framing.

Fact Sheets

If we are to mitigate the human impact on climate change, it is going to involve major changes to human behavior. While this must include wide-sweeping policy changes, in a capitalistic democracy, that also means communicating the science and the necessary solutions clearly to the public, both so that small-scale changes can be made and so that the belief in the need for larger changes can influence policy makers (Dietz et al., 2009). While there may be lower trust in science coming from universities (PEW, 2017), extension programs within those universities may still be a trusted resource as they have served as a reliable mediator between the universities and rural communities. Fact sheets published in partnership with these extension agencies, then, provide an opportunity to engage with these communities quickly in a familiar genre that gets right to the point. Because of the brevity, however, it is important that they not spend page space on information their audience will perceive as unnecessary or biased. These fact sheets are a perfect example of a genre that can benefit from dissociative framing as outlined here.

To consider how some technical communicators are working in rural communities, this article will briefly examine two examples of these fact sheets published through the Utah State University Extension Office for their current rhetorical strategies, consider the audience, and offer suggestions for how a dissociative framing model would change these strategies. These fact sheets, written by students and researchers at Utah State, demonstrate one type of rhetorical strategy that is currently employed by scientists trying to persuade people to create adaptive behaviors in the face of climate change rooted in the assumption that an understanding of the human causes of climate change will motivate action (the knowledge deficit model).

The goal of this article is not to diminish the work of these authors or to imply that these fact sheets were not written with great care and thoughtfulness—in fact, I am certain they were. The goal is to consider how these fact sheets may be construed by a rural Utah audience and how future fact sheets and similar genres could be written to better engage rural communities in adapting behaviors with regard to the environment.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Climate change has been recognized widely by the scientific community to be accelerated by human activity, most notably by fossil fuel consumption, deforestation, and activities increasing ocean acidification (Cox et al., 2000; Dansgaard et al., 1993; IPCC, 2014; IPCC, 2018; Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). While a large focus has been placed (rightly) on changing policy to mitigate the human impact on climate change, household actions could create a “wedge” to curb the dramatic rise in carbon (Dietz et al., 2009), and some sociological studies have suggested that creating environmentally friendly habits in individuals cultivates a stronger environmental ethic and support for protective and proactive legislation (Bina & Vaz, 2011). Whether the emphasis on mitigating climate change should be in creating and changing policy or in changing individual behavior, technical communications that focus on informing and empowering changes in everyday behaviors work toward both of these goals.

Palmer and Killingsworth’s EcoSpeak (1992) introduced technical communication to the concept of eco-humanism, the philosophy that human interests are intertwined with environmental interests, and the authors argue environmental communication should draw attention to this bond between humans and the natural world. Unfortunately, with a dramatic increase in venues for airing of opinion and “facts” (social media, town hall meetings, online public fora, etc.), especially when it comes to environmental issues, we have seen an increased polarization of attitudes toward nature, and subsequently climate change. Still, eco-humanism has become a common theme in technical communication scholarship, and with good reason. Palmer and Killingsworth also emphasize careful analysis to understand an audience’s relationship to nature to more appropriately frame scientific information. This is a great step toward getting rid of the simple assumption that we must first convince an audience to accept climate change science before they will act on it. Yet there are broader questions worth asking, primarily whether or not it matters if acceptance of climate change science must precede behavioral change, and if trying to force such acceptance might actually do more damage by associating the environmentally friendly behaviors and policies with publicly rejected and politicized science.

Scholars in technical communication have since demonstrated the need to engage stakeholders directly in scientific literacy and communication (Druschke & McGreavey, 2016; Simmons, 2008), but this work can take years we do not have and may overlook stakeholders who do not have a voice. From a social justice standpoint, it is imperative that technical communicators move audiences toward fast action, as those most impacted tend to be marginalized groups that have limited access to resources (IPCC, 2014). We have passed the point of having the luxury of patiently changing individuals’ attitudes through deliberative civic engagement and participation in the science. The focus needs to shift toward direct engagement and participation in the solutions.

While stakeholder engagement is certainly important work for the long term, in the short term, we can empower individuals to take action by framing that action around immediate benefits. While continuing efforts to increase scientific literacy in underserved communities, we can also utilize existing avenues of communication and practice dissociative framing to make necessary environmental action palatable and engage stakeholders in being part of the solution.

While scholars in the field may have recognized the exigency for more complex rhetorical models than the knowledge deficit model, Cagle and Tillery’s (2015) review of science communication research across multiple disciplines revealed that much of the literature is still reliant on a one-way communication model, and some scholarship they analyzed argues that the deficit model has something to offer climate change communication practice. Cagle and Tillery call for technical communicators to act as advocates in risk communication, including risks exacerbated by climate change, and for more targeted forms of audience analysis. What is needed is a rhetorical strategy for climate change communication that does not rely on the knowledge deficit model. Dissociative framing offers such a strategy.

DISSOCIATIVE FRAMING

In the field of communication science, the concept of framing is well-studied and demonstrated to be a productive heuristic for considering what makes for effective communication (Nisbet, 2009, 2010; Scheufele, 2004), and framing has been applied by researchers in other fields as well, including health (Koon et al., 2016), technology (Granqvist & Larulia, 2011), and climate change (Dickinson et al., 2013). Matthew Nisbet’s work on rhetorical framing suggests that tailored frames offer a way to jump party lines. Nisbet mentions it is important to first recognize that “Framing is an unavoidable reality of the communication process,” that whether we are aware of it or not, we are framing an issue whenever we communicate about it, and we can be more effective if we are aware of it (2009, p. 15). Nisbet (2010) uses an example of the National Academy of Science persuading the public of evolution as a foundation for biology classes. The frames the authors found to be effective allowed for co-existence of faith and evolution: rather than focusing on divisive aspects of the debate, framing evolution as the pathway to advances in modern science was far more acceptable to the public. By affirming that faith and science can co-exist, the authors allowed the audience to be more comfortable with scientific theories they had previously outright rejected.

Herndl, Rockenbach, and Ritzenburg (2014), like Nisbet, acknowledge that facts are not enough. In their appendix to Herndl’s edited collection Sustainability: A reader for writers, the authors recommend appealing to emotions as well as to logic (pathos and logos) by connecting a human story, narrative, or other rhetorical appeal to the facts of the problem. They also recommend that the author consider what rhetorical appeal (or frame) might work for a specific audience or else make a broad range of appeals to fit a broad audience. In either case, Herndl et al. recognize that multiple appeals of rhetoric must be engaged in order for climate change communication to be effective.

Framing offers a way to acknowledge the importance of a unique audience’s values and beliefs when communicating science. The trouble is that the facts themselves have become politicized and are already associated in most people’s minds with certain ideologies. As with evolution, the evidence regarding climate change has been accessible long enough for people to align themselves with one side or the other; the work of the technical communicator is to reach past those alignments. This is where the idea of dissociation becomes important when we are not only communicating facts but attempting to persuade our audience to change behaviors or when behaviors become more important than beliefs, as is now the case with climate change.

Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969) defined dissociation as “techniques of separation which have the purpose of dissociating, separating, disuniting elements which are regarded as forming a whole or at least a unified group within some system of thought: dissociation modifies such a system by modifying certain concepts which make up its essential parts” (p. 190). Unlike framing, dissociation has not been studied as thoroughly or empirically in the field of communication, but scholars have studied its efficacy for political and legal argumentation (Lynch, 2006; Ritivoi, 2008; Stahl, 2002). While technical communicators might strive to remain unbiased and avoid politics altogether, dissociative framing offers a way to present information that is often cognitively connected to political issues without politicizing it.

Dissociative framing considers not only what frame is going to be effective but also how to make communication more impactful by removing associations that create cognitive dissonance given specific tribalisms we know to be present in a given audience. For example, a communicator separating the idea of renewable energy resources from the objectionable concept of climate change allows for open discussion of solar plants and wind farms without wading into the complicated networks of tribalisms and ideologies associated with climate change, even if mitigating climate change is the original goal of the communicator. By dissociating these adaptive behaviors from the abstract and potentially controversial issue of climate change and constructing a rhetorical frame that re-associates them with tangible and uncontroversial results (saving money, becoming industry leaders, creating jobs), technical communicators can work toward cutting those complex associations and make these ideas of clean energy, tree planting, and other adaptive behaviors compatible with our audience’s beliefs and concerns. If we do not pair suggestions for making these behavioral changes with the idea of climate change, if we instead solely frame the behavior as compatible with existing values, the suggestions can be accepted even for someone who outright dismisses climate change science.

I am certainly not advocating that dissociative framing replace all science communication and that we cease to translate complex and highly politicized climate change data. It is still incredibly important that we continue to work toward building scientific literacy, especially in underserved communities such as rural areas. The perceived alienation of marginalized rural communities by the scientific community (Parker, 2018) may be a contributor to the very associations that render a need for dissociative framing. However, while the science is still considered controversial and political, and while it has also been demonstrated that increased understanding of climate science does not lead to increased action (personal or political) dissociative framing can help technical communicators persuade audiences to take the necessary actions. Ultimately, these actions can help reduce their carbon footprint toward placing the “wedge” on carbon emissions (Dietz et al., 2009) while we continue to attempt to influence policy and larger corporate changes.

When it comes to this kind of complex, multidisciplinary, global problem, digestible genres like fact sheets need to be designed to engage individuals quickly, without expending limited page space on the “controversial” scientific concepts, and with the intent of getting their informed involvement in creating sustainable, resilient, and adaptive behaviors. The limitation of their short length should be seen by authors as an opportunity to move past denial of climate change and develop other frames that work toward encouraging action. Dissociative framing as a rhetorical strategy is a way to quickly persuade audiences to take necessary action.

EXAMPLE: EXTENSION FACT SHEETS

I have closely examined the rhetorical strategies employed in two fact sheets—both from the Utah State Extension office—whose goal is to empower their audience to make some kind of behavioral adaptation toward mitigating the individual’s contribution to climate change. Fact sheets are short, succinct presentations of information on home gardening, agriculture, natural hazard preparedness, local fishing and hunting, and other home and life improvement topics as well as reports on the research produced by the university. They are designed to provide quick bites of information to members of the community about the research going on at the university and to synthesize research from other institutions that may be relevant but not easily accessible.

Fact sheets are usually written either by students getting some experience synthesizing research or by faculty working alone or with students to translate research into language more easily understood by the general public. Fact sheets provide an example of science writing, usually taught by technical communication and composition instructors, and reflects the lessons learned in those classrooms. The fact sheets analyzed here cover two different approaches to mitigating climate change, but both of these approaches focus on things that can be done at the household level (saving energy and planting trees.) Both are also framed around the impact these actions have on climate change. These examples demonstrate that there is a need for technical communicators to develop comprehensive rhetorical strategies for these community action-oriented genres that do not rely upon the deficit model and to teach these models in the technical communication classroom.

It is important to note before looking at the examples that in most rural counties in Utah, many citizens are employed by the coal mining industry, and a good deal of the Western United States’ fossil fuels are processed here (Millard, Emery, Sanpete, Sevier, San Juan, and Carbon Counties). These areas tend to run strongly conservative on most issues and tend to more strongly deny human causes of climate change than the rest of the country (Howe et al., 2015). For example, Millard and Emery counties each deviate about negative 15 points from the national average on climate change acceptance (Howe et al., 2015). Yet, these rural Utah counties also express overwhelming support for funding research into renewable resources. That support is still a few points below the national average, but at 80% in both Millard and Emery counties, this is perhaps an unexpected stance in the heart of Western coal and cattle country (Howe et al., 2015). We know, then, that there is an understanding of the need for long-term economic stability in the area and that there is overwhelming support for new developments toward that stability. We also know that while renewable energy infrastructure is less widely accepted, it is still more acceptable to this audience than the idea that humans are contributing to climate change.

By contrast, the authors of these fact sheets are situated in Logan, a university town that is far more likely to accept that humans are contributing to the causes of climate change (Howe et al., 2015), and they are embedded in academic departments in which denial of climate change science is rare and likely discouraged. When I began this research, I assumed that the authors’ primary audience was rural communities in Utah. After discussing my work with a colleague who is more closely connected to one of the authors, I learned that, in fact, these sheets are often written with university donors in mind as the primary audience and rural communities as the secondary audience. Donors are more likely situated close to the university if they are in Utah at all. They are looking at fact sheets not for their content but as an example of the university engaging in outreach. These authors are under conflicting influences, so some of the complications with writing in such limited genres involves writing for a diverse set of audiences. However, these sheets are still a prime opportunity for researchers at the university to engage rural communities, and considering rural communities as a primary audience would not negate the donors as a secondary audience.

Methods

Methods

The two fact sheets (see Figures 1 and 2) analyzed here were chosen because they explicitly encourage behaviors toward mitigating climate change and therefore provide an example of how some extension documents are currently modeled toward this goal. They are not intended to serve as a representative data set, rather as examples of models that do not use dissociative framing. In conducting a coded rhetorical analysis of two examples of this genre, I do not intend to imply that all fact sheets are written in the same way or with the same audience analysis approach. Rather, these examples demonstrate that there is potential for a new approach that would be more mindful of the audience’s values and attitudes.

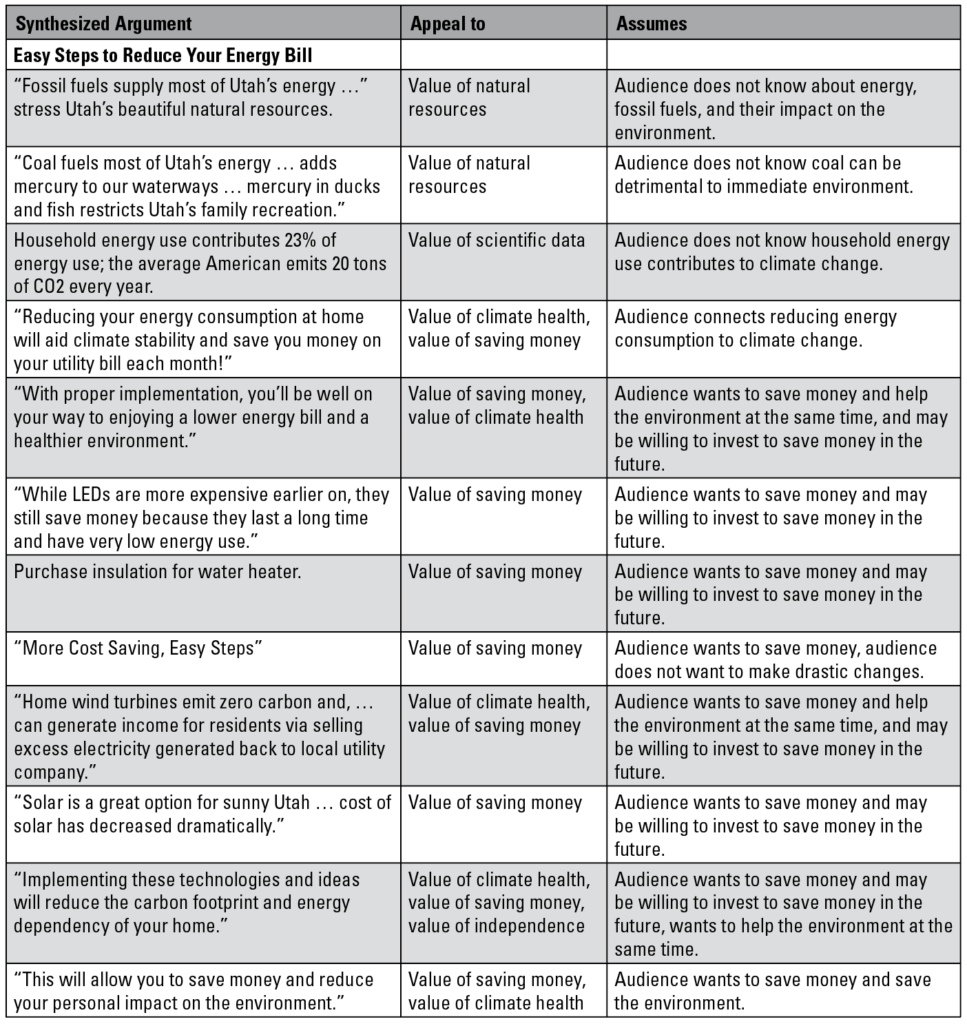

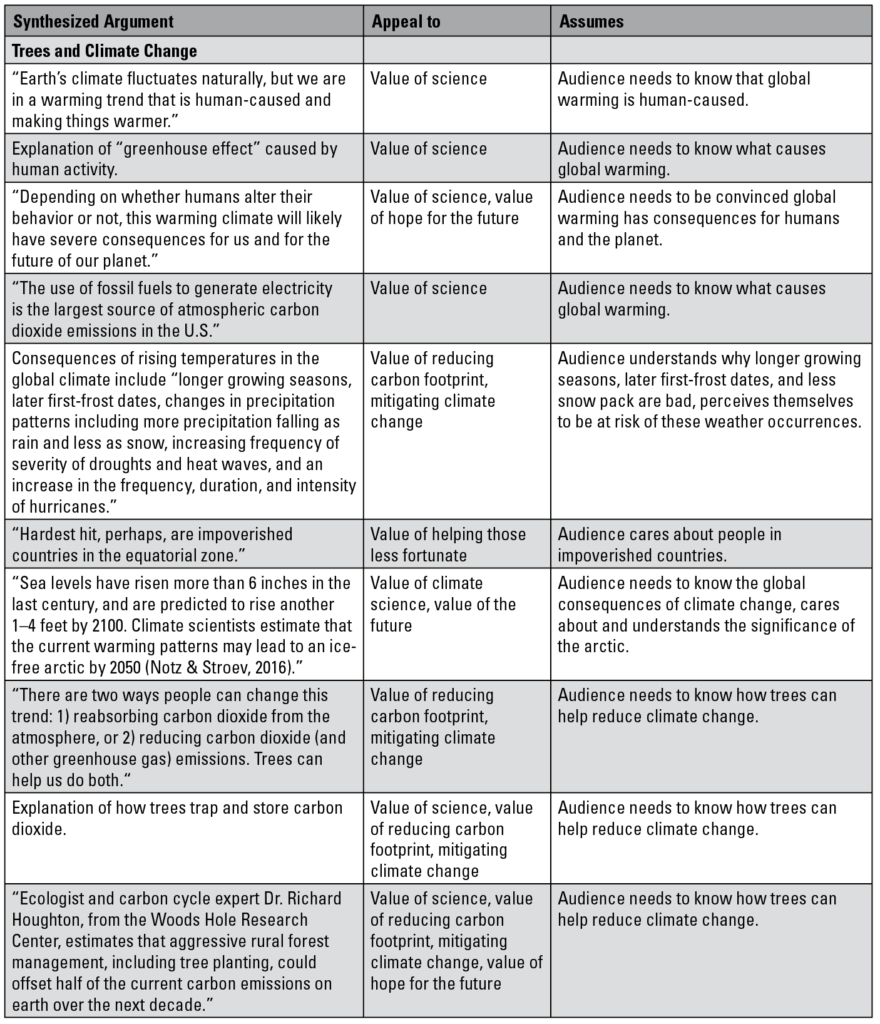

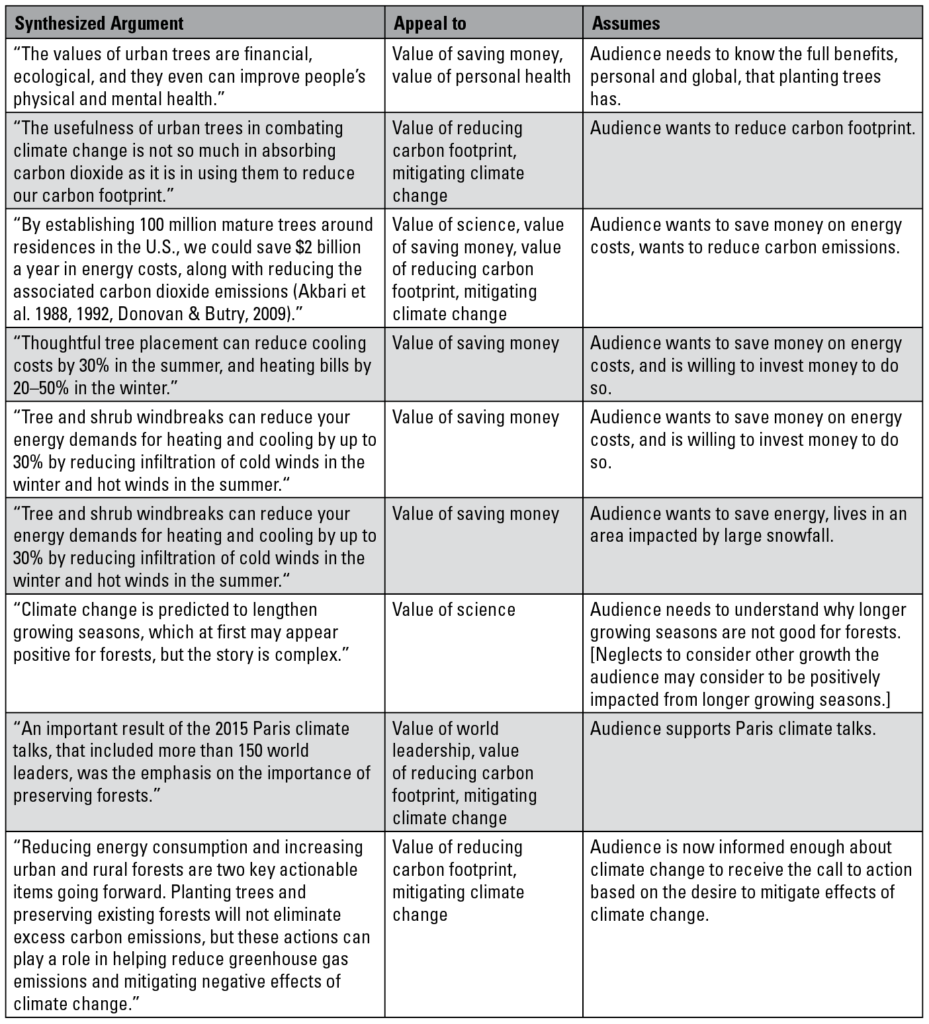

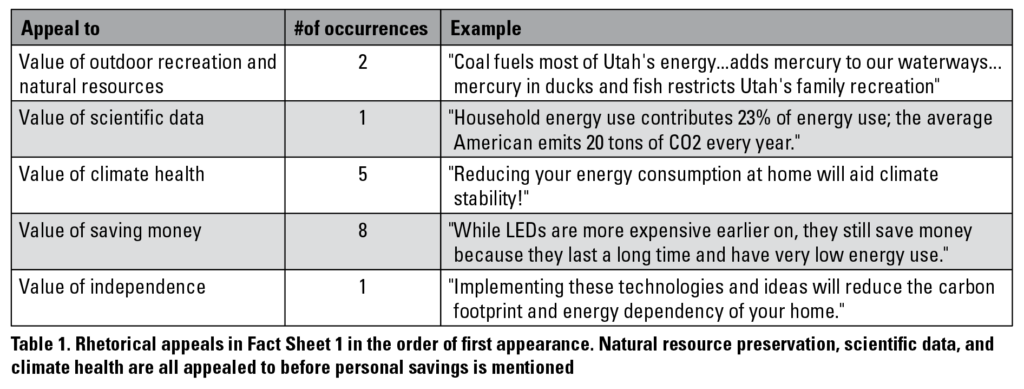

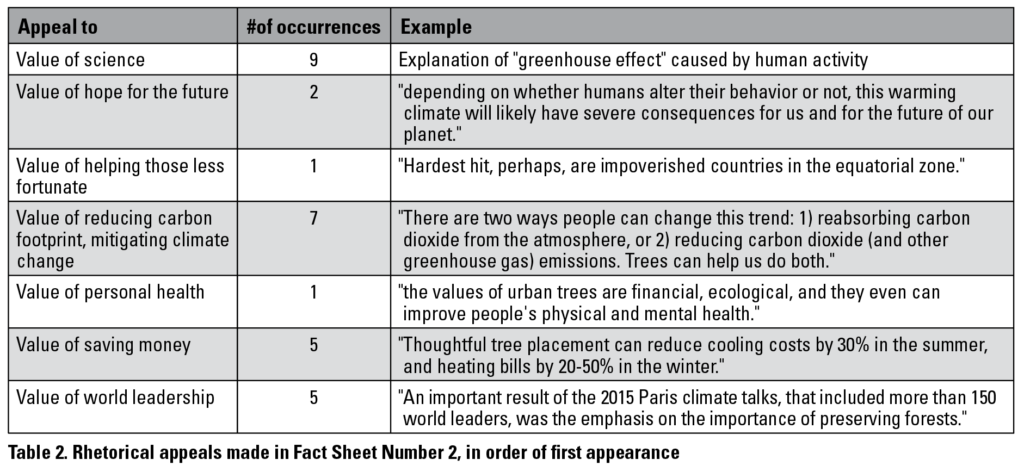

To assess the framing strategies of these fact sheets, I first tagged and coded their argument appeals. I used an open coding methodology, meaning instead of having a set of predefined codes, I made a note of the appeals and identified what values the authors were appealing to (see Appendix A); I then developed categories based on the recurring themes and noted the number of occurrences of each of these appeals (see Tables 1 and 2), including overlaps of those occurrences. Finally, I used those codes and categories to model the communication frames that are revealed in these fact sheets and describe what assumptions were made about the audience based on the frames used to encourage the different adaptive behaviors. I then conducted a holistic analysis of the assumptions made and the values perceived in each fact sheet to draw conclusions about what frames the authors are working within. In my discussion, I also include findings from external research to suggest what alternative frames might be more effective with these particular audiences and to suggest why climate change acceptance need not be, and even in some cases should not be, a precursor to recommending these behavior changes.

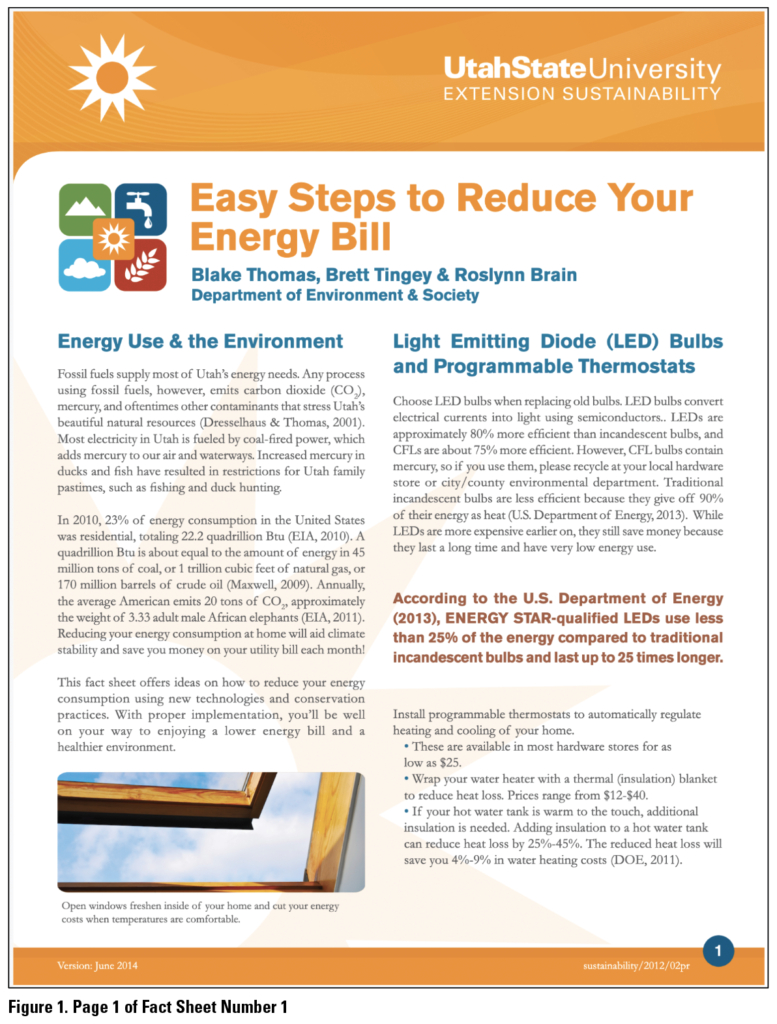

Fact Sheet Number 1: “Easy Steps to Reduce Your Energy Bill”

Summary

This fact sheet begins by discussing the dangers of burning fossil fuels (coal in particular) and connecting it to the detriment of Utah’s air, water, and other natural resources. The next paragraph cites statistics on overall energy consumption in the United States and how much the average American contributes to that each year. Slightly more than one page of the two-page fact sheet lists ways to reduce your energy bill and includes some of the basic science behind why those changes are more energy efficient for things like installing LED light bulbs, home wind turbines, and solar panels. The fact sheet is short and uses plain language, citing prominent climate science research, but the framing of the fact sheet reveals that the real motivation the authors have for writing this is to inform and encourage people to protect the environment, a sharp turn from the title’s suggestion to save money. The fact sheet frames an argument for behaviors to reduce energy around the human impact on climate change and associates those behaviors with attacks on the fossil fuel industry.

Analysis

While the fact sheet has eight rhetorical appeals to the value of saving money, these appeals are buried and scattered behind descriptions of climate change and link to human activity, a rhetorical move that risks losing the audience’s interest altogether. As the fact sheet begins heavy on climate science, it reflects the deficit model. By beginning with communicating the larger environmental problem in plain language, the authors demonstrate their belief that access to climate science is what will motivate people to action, and by associating the issue with our air, water, and recreation in two swift sentences, they attempt to drive home the long-denied science and persuade their audience to accept.

The title acknowledges that there may be other factors that have nothing to with climate change that would motivate people to make these adjustments, but the immediate shift with the first paragraph appears somewhat misleading, like a rhetorical bait-and-switch. Notably, the immediate reference to fossil fuels brings up a real problem for many in the state of Utah. Recall that in many of the rural communities these fact sheets are intended to reach, fossil fuels are a major source of income, and citizens in these counties that rely on coal mining for their livelihoods are among the least likely to accept climate change or trust climate scientists (Howe et al., 2015). As more power companies switch to more renewable energy sources (often at the request of consumers), coal production is down, and plants are closing all over the state. The request that the audience reduces their own fossil fuel consumption, especially coal, by making these behavioral and lifestyle adaptations ignores the very tenuous political environment in these rural communities. The audience in rural Utah is likely to respond negatively and dismissively to any scientific information that begins by blaming their community’s primary industry. Advising on how to reduce an electric bill is one thing; associating that action with changes that may diminish a community’s livelihood is another.

Implications

Implications

A dissociative framing approach to these fact sheets might look first at the communication goals and consider why people might be motivated to change behaviors in these communities. For example, these rural communities tend to be in topographically flatter areas, unlike Logan where Utah State is situated between two mountain ranges. The campus is prone to heavy smog due to seasonal inversion, a naturally-occurring process by which cold air gathered between mountain ranges traps warm air; in trapping that warm air, the inversion also traps heavy amounts of pollution that would otherwise rise up into the greater atmosphere, resulting in what is known as a red air day. On these days, the air is tangibly polluted and it becomes difficult to breathe. Because of the flat topography, the counties where most coal mining takes place do not experience this phenomenon, even though coal burning contributes to it. The damage that fossil fuels do to our air is not as visible to an audience in rural Utah as it is to the authors in the valley town. Inversions may be recognized as an urban problem, as they occur far more in the urban centers of the state, including Salt Lake City. Appealing to rural citizens for help in reducing this largely urban problem may even create associations with rural-urban tensions. The way the science of climate change is introduced in this fact sheet assumes that the audience simply does not know about the issue and the impact of coal on the environment, when the problem is that the issue is deeply politicized. Framing the actions the audience needs to take around these issues drives negative associations with those political issues, when a frame that dissociates them could be far more effective.

Such a limited genre has to balance between being concise and being considerate of the values and environmental attitudes of the intended audience. The hook is in the monetary benefit of making these changes. Regardless of the acceptance or denial of climate change, the audience can appreciate the information and be empowered to reduce their energy consumption. I would never argue that we should ignore science or avoid an opportunity to increase scientific literacy. However, with such a short amount of space, the fact sheet may be more effective by avoiding controversial topics and considering a more tailored, dissociative frame.

Fact Sheet Number 2: “Trees and Climate Change”

Summary

The second fact sheet is somewhat longer (7.5 pages including references) and also begins with an overview of the science of climate change. The authors go into much more depth in tree science, including the specific details of how deforestation affects climate change, the immediate climate of the Global South, and how planting more trees can combat climate change. The frame of this fact sheet is similar to that of the first: Introduce the big problem and the evidence of that problem, then move to what can be done about it—the traditional format found in research papers and proposals.

The first 2.5 pages are dedicated to reiterating the science that explains climate change and why it presents a problem for nature and for humans in the long run. The authors move from what is causing the climate to change to what effects this change is already having and is predicted to have. The next 2.5 pages explain the science of how trees can be used to combat climate change. The next page (6) abruptly jumps to other possible reasons that planting trees in your own yard is a good idea: reduced energy demand, shade, a reduced energy bill, and controlled snow deposits. For the first reason, the authors here cite some studies that say that planting 100 million trees in cities could save $2 billion a year in the United States, though how exactly this happens or who gets to keep that money is not explained. The second reason is more straightforward: Plant a tree in your yard and you could actually reduce your summer air conditioning cost by up to 30 percent and reduce your winter heating cost by up to 50 percent. This is because the tree provides both shade and insulation if planted in a proper place. The third reason is that trees can break cold and hot winds, again reducing your heating and air conditioning bills. The last is that trees can control snow deposits, “reducing the energy required to plow roads, parking lots, and driveways” (p. 7). Finally, the last page pans out quickly from the homeowner’s yard to bring the fact sheet back to the global issue of climate change, forming an association between local tree planting and global forest preservation.

Analysis

Analysis

The title strongly reflects the authors’ motivation for writing this fact sheet but leaves some mystery as to the usefulness of the content for a non-scientific audience. The first few sections also reflect the deficit model by focusing on the science of trees and climate change upfront, while the personal benefits of planting a tree are buried toward the end. What might really motivate the adaptive behavior recommended is the savings in energy bills and overall more stable temperatures in the hometown, but that gets lost in the highly politicized science of global climate change. Deforestation of the rainforest has been happening and on the public’s radar for the last century, so why would an audience in rural Utah care about it now?

Again, this fact sheet reflects the rhetorical strategy that frames an argument for action around climate change. The heavy emphasis on what is causing climate change, what will happen as a result, and how it can be mitigated takes away from the potential the fact sheet has to encourage people to plant more trees and to empower them to be part of a greater solution. It assumes that in order for people to be convinced to do this, they have to accept the science of climate change, and in doing so, it associates planting trees with one side of a highly politicized issue. While this audience may be turned away from the rest of this fact sheet because of the focus on an incompatible idea (climate change science), they may be interested in the information about how planting trees can improve their own lives.

Implications

A dissociative frame might instead avoid talking about the broader science and offer more space on the immediate effects on the individual taking action, on advice for planting the tree, location, watering, what types of trees do well in this climate, etc. Planting trees is already often associated with environmental activism, and therefore may be seen as taking a political stance.

A dissociative frame would remove consideration for the greater environment and instead work to inform the audience of the localized benefits to planting trees. This would empower them with specific details on how to most effectively implement this change, by dissociating tree-planting from tree-hugging and forming new associations between tree-planting and values such as saving money, improving home value, and building local resilience.

DISCUSSION

Although improving scientific literacy is important, especially when it comes to issues that put life on this planet at risk, shorter, more limited genres are not the place to try to push research on what the audience considers a controversial topic. It is important for technical writing students and practitioners working in such limited genres to understand that climate change is perceived as controversial and that framing these behavior changes around mitigating climate change or reducing fossil fuel use may actually have the opposite of the intended impact. What may be reiterated constantly and consistently in the halls and classrooms of a university’s natural resources department may be tied to more complicating factors in the rural areas those researchers are meant to be benefiting.

These documents should reflect the value system of the audience, focusing on what is going to get the community to engage constructively. These areas are impacted by dwindling water availability and by a rising heat index; the communities most uniquely reached by this genre of Utah State Extension fact sheets are prone to climate change denial, but they are also in favor of funding renewable energy (Howe et al., 2015). They are also closely connected to fossil fuel industries. Whether they make their living mining coal or not, they are surrounded by it, and they are impacted daily by the powerful rhetoric of the coal industry. A dissociative frame for these fact sheets would avoid discussion of climate change and coal mining altogether and re-associate the recommended behaviors with positively held values, such as saving money and building a more resilient community. By looking at this audience closely and considering the existing associations with climate change data and fossil fuel industries, authors can better strategize communication for the complex connections that form human attitudes and motivate behaviors. In doing so, technical communicators find unexpected avenues for encouraging behavior changes.

In any given community, there are distinct and easily discernible factors that contribute to attitudes toward the environment and climate change science. These factors impact how certain frames of climate change communication are interpreted, but they may also expose avenues for encouraging support for adaptations and adaptive behaviors themselves. A dissociative frame for Fact Sheet Number 1 would cut all mention of climate change and the fossil fuel industry and instead re-associate the energy-reducing behaviors with values like saving money and creating job opportunities; a dissociative frame for Fact Sheet Number 2 would also cut all reference to climate science and the role trees play in regulating Earth’s atmosphere and would re-associate tree planting with positive personal values, such as saving money and increasing the value of one’s home and the local community.

Thinking past denial of climate change in framing behaviors and even policy can open up new frames for encouraging the changes that are needed to mitigate the effects of climate change. Dissociative framing allows the communicator to consider what new associations may be formed that can be more persuasive than pre-existing and highly politicized science.

CONCLUSION

Technical communicators are in a unique position to advise scientists and others working to persuade the public to take specific actions with regard to climate change, and they teach future scientists and technical writers. Especially when writing and speaking in shorter genres such as fact sheets, it may be crucial to practice dissociative framing to avoid correlations that are perceived to be controversial and to associate necessary actions with positive values.

From EcoSpeak onward, the field of technical communication has been aware that audiences are complex in their relationships to nature; a thorough understanding of climate change is not necessary to motivate environmentally-minded action. But much of science communication has continued under the assumption that climate change acceptance must come before climate change action. Dissociative framing allows technical communicators to move around the blockade of denialism in the “Post-Fact era” and focus their arguments instead on creating positive associations with adaptive behaviors. They can dissociate these behaviors from politicized science and move around denial straight on toward action.

I recommend practitioners consider the following questions when engaging communities in shorter, action-oriented genres:

- What ideas and terms have come to be politicized with this audience? What might I need to dissociate from the behaviors I want them to adopt or ideas I want them to consider?

- What are the major industries in this area? How are these industries both impacting and impacted by climate change?

- Based on the answers to the previous question, what topics and frames might we want to avoid?

- What sort of natural environment is the audience a part of, and what are the challenges within that environment?

- What other values might this audience have besides environmental concerns (saving money, saving time, religious values, community values, etc.)? How might those values be re-associated with the behaviors or attitudes we want them to adopt?

Teachers of technical communication also have a unique opportunity to encourage students to utilize appropriate rhetorical strategies when writing about important scientific information. Students are acutely aware that science has become highly politicized, from climate change to vaccinations to genetically-modified organisms, and they are often already invested in finding ways to break down barriers between scientific research and their local or home communities. Technical communication instructors can engage their students in thinking beyond the deficit model to find unique ways of conveying important scientific information to a variety of audiences. This heuristic approach may begin by asking them to think about what people in their communities care about most and what they are most invested in. Having students list out what their communities care about and the major takeaways they want to convey to that community may help them to seek out new connections and new avenues of scientific engagement. It may also help them think beyond the deficit model toward an approach like dissociative framing.

With the climate changing more rapidly and risks of natural disasters increasing every day, we do not really have time to spend designing our arguments first to overcome climate change denialism and then to persuade to action. With short genres that have the ability to reach otherwise disengaged and dismissive audiences, writers need to spend the time and page space getting right to the point and presenting alternative reasons for making the adaptive behaviors and creating new associations with those behaviors. Frames toward creating adaptive behavior should be focused on tangible effects of those behaviors that extend beyond what seems abstract or controversial to the audience. By creating rhetorical frames that dissociate necessary action from controversial and unpalatable ideas, technical communicators can focus on forming good environmental habits regardless of acceptance or denial of climate change.

REFERENCES

Bazerman, C. (1988). Shaping written knowledge: The genre and activity of the experimental article in science. University of Wisconsin Press.

Bina, O., & Vaz, S. G. (2011). Humans, environment and economies: From vicious relationships to virtuous responsibility. Ecological Economics, 72, 170–178.

Blythe, S., Grabill, J. T., & Riley, K. (2008). Action research and wicked environmental problems: Exploring appropriate roles for researchers in professional communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 22(3), 272–298.

Cagle, L. E., & Tillery, D. (2015). Climate change research across disciplines: The value and uses of multidisciplinary research reviews for technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 24(2), 147–163.

Ceccarelli, L. (2011). Manufactured scientific controversy: Science, rhetoric, and public debate. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 14(2), 195–228.

Chambers, R. (1983). Rural development: Putting the last first. New York, NY: Routledge.

Coppola, N., and Karis, B. (Eds.). (2000). Technical communication, deliberative rhetoric, and environmental discourse: Connections and directions (Vol. 11). Greenwood Publishing Group.

Cox, P. M., Betts, R. A., Jones, C. D., Spall, S. A., & Totterdell, I. J. (2000). Acceleration of global warming due to carbon-cycle feedbacks in a coupled climate model. Nature, 408(6809), 184–187.

Dansgaard, W., Johnsen, S. J., Clausen, H. B., Dahl-Jensen, D., Gundestrup, N. S., Hammer, C. U., Hvidberg, C. S., Steffensen, J. P., Sveinbjörnsdottir, A. E., Jouzel, J., & Bond, G. (1993). Evidence for general instability of past climate from a 250-kyr ice-core record. Nature, 364(6434), 218-220.

Davenport, C. (2019, September). Trump to revoke California’s authority to set stricter auto emissions rules. The New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/17/climate/trump-california-emissions-waiver.html

Dettenmaier, M., Kuhns, M., Unger, B., and McAvoy, D. Utah State University Forestry Extension. (2017). Trees and climate change. (Paper 1764).

Dickinson, J. L., Crain, R., Yalowitz, S., & Cherry, T. M. (2013). How framing climate change influences citizen scientists’ intentions to do something about it. The Journal of Environmental Education, 44(3), 145–158.

Dietz, T., Gardner, G. T., Gilligan, J., Stern, P. C., & Vandenbergh, M. P. (2009). Household actions can provide a behavioral wedge to rapidly reduce US carbon emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(44), 18452–18456.

Druschke, C.G. (2014). With whom do we speak? Building transdisciplinary collaboration in rhetoric of science. Poroi, 10(1).

Druschke, C. G., and McGreavy, B. (2016). Why rhetoric matters for ecology. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(1), 46–52.

Fears, D. (2019, September). The Trump administration weakened Endangered Species Act rules—17 state attorneys general have sued over it. The Washington Post. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2019/09/25/trump-administration-weakened-endangered-species-act-rules-today-state-attorneys-general-sued-over-it/

Granqvist, N., & Laurila, J. (2011). Rage against self-replicating machines: Framing science and fiction in the US nanotechnology field. Organization Studies, 32(2), 253–280.

Gross, A. (1996). The rhetoric of science. Harvard University Press.

Hale, T. M., Cotten, S. R., Drentea, P., & Goldner, M. (2010). Rural-urban differences in general and health-related internet use. American Behavioral Scientist, 53(9), 1304–1325.

Herndl, C. G., Rockenback, B., & Ritzenburg A. (2014). Rhetorical Strategies and Writing for Change. Sustainability: A reader for writers. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Herndl, C. G., & Cutlip, L. L. (2013). “How can we act?” A praxiographical program for the rhetoric of technology, science, and medicine. Poroi, 9(1), 9.

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., Bain, P. G., & Fielding, K. S. (2016). Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nature: Climate Change, 6(6), 622–626.

Howe, Peter D., Mildenberger, M., Marlon, J.R., & Leiserowitz, A. (2015). Geographic variation in opinions on climate change at state and local scales in the USA. Nature Climate Change, 5, 596–603. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2583

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2014). Climate change 2014–Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: Regional aspects. Cambridge University Press.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C: an IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Retrieved from www.ipcc.ch

Joswiak, R. & Duncan, M. (2020). Inform or persuade? An analysis of technical communication textbooks. Technical Communication, 67(2), 29–41.

Keith, W. (1997). Science and communication: Beyond form and content. In James H. Collier and David M. Toomey (Ed.), Scientific and technical communication: Theory, practice, and policy (pp. 299–326). Sage Publications.

Kellstedt, P. M., Zahran, S., & Vedlitz, A. (2008). Personal efficacy, the information environment, and attitudes toward global warming and climate change in the United States. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 28(1), 113–126.

Knoblauch, C. H., & Brannon, L. (1984). Rhetorical traditions and the teaching of writing. Boynton/ Cook.

Koon, A. D., Hawkins, B., & Mayhew, S. H. (2016). Framing and the health policy process: a scoping review. Health policy and planning, 31(6), 801–816.

Kynell, T. (1994). Considering our pedagogical past through textbooks: A conversation with John M. Lannon. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 24(1), 49–55.

Lazo, J. K., Kinnell, J. C., & Fisher, A. (2000). Expert and layperson perceptions of ecosystem risk. Risk Analysis, 20(2), 179-194.

Lynch, J. (2006). Making room for stem cells: Dissociation and establishing new research objects. Argumentation and Advocacy, 42(3), 143–156.

McGreavy, B., Druschke, C. G., Sprain, L., Thompson, J. L., & Lindenfeld, L. A. (2016). Environmental communication pedagogy for sustainability: Developing core capacities to engage with complex problems. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 15(3), 261–274.

Nisbet, M. (2009). Communicating climate change: Why frames matter for public engagement. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 51(2), 12–23.

Nisbet, M. (2010). Framing science: A new paradigm in public engagement. In L. Kahlor & P. A. Stout (Eds.), Communicating science: New agendas in communication (pp. 40–67). New York, NY: Routledge.

Ornatowski, C. M. (1992). Between efficiency and politics: Rhetoric and ethics in technical writing. Technical Communication Quarterly, 1(1), 91–103.

Palmer, J.S., and Killingsworth, M. (1992). Ecospeak: Rhetoric and environmental politics in America. Southern Illinois University Press.

Parker, K. (2018). Similarities and differences between urban, suburban and rural communities in America. Retrieved March 23, 2021, from Pewresearch.org website: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/05/22/what-unites-and-divides-urban-suburban-and-rural-communities/

Parmesan, C., & Yohe, G. (2003). A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature, 421(6918), 37–42.

Perelman, C., and Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation [by] C. Perelman and L. Olbrechts-Tyteca. Translated by John Wilkinson and Purcell Weaver.

Pew Research Center. (2017). Sharp partisan divisions in views of national institutions. Retrieved March 23, 2021, from Pewresearch.org website: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/07/10/sharp-partisan-divisions-in-views-of-national-institutions/

Rabinovich, A., Morton, T. A., Postmes, T., & Verplanken, B. (2012). Collective self and individual choice: The effects of inter-group comparative context on environmental values and behaviour. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51(4), 551–569.

Ritivoi, A. (2008). The dissociation of concepts in context: An analytic template for assessing its role in actual situations. Argumentation and Advocacy, 44(4), 185–197.

Roser-Renouf, C., Maibach, E., Leiserowitz, A., and Rosenthal, S. (2016). Global warming’s six Americas and the election, 2016. Yale University and George Mason University. New Haven, CT: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

Salemink, K., Strijker, D., & Bosworth, G. (2017). Rural development in the digital age: A systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies, 54, 360–371.

Scheufele, B. (2004). Framing-effects approach: A theoretical and methodological critique. Communications, 29(4), 401–428.

Simmons, W. M. (2008). Participation and power: Civic discourse in environmental policy decisions. SUNY Press.

Stahl, R. (2002). Carving up free exercise: Dissociation and “religion” in Supreme Court jurisprudence. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 5(3), 439–458.

Stetch Ferek, K. and Puko, T. (2019, September). EPA rolls back Obama-era regulations on clean water. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/epa-to-roll-back-obama-era-regulations-on-clean-water-11568300216

Tebeaux, E., & Dragga, S. (2018). Essentials of technical communication (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Thomas, B., Tingey, B., and Brain, R. (2014). Utah State University Extension, Sustainability. Easy steps to reduce your energy bill. (Paper 1502).

Toulmin, S. (2003). The uses of argument. Cambridge University Press.

Walsh, L. (2013). Resistance and common ground as functions of mis/aligned attitudes: A filter-theory analysis of ranchers’ writings about the Mexican Wolf Blue Range Reintroduction Project. Written Communication, 30(4), 458–487.

Whitacre, B. E., & Mills, B. F. (2007). Infrastructure and the rural–urban divide in high-speed residential Internet access. International Regional Science Review, 30(3), 249–273.

United States Census Bureau. (2010). Geography: Urban and Rural [Data file]. Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/urban-rural.html

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Beth J. Shirley is an Assistant Professor of Technical Communication and Rhetoric at Montana State University, where she teaches Technical Writing and Digital Rhetorics courses. Her research focuses on understanding local ontologies and prioritizing local knowledge toward engaging rural communities in science communication as well as how human relationships with both nature and technology play a role in that engagement. She can be reached for questions at bethshirley@montana.edu.

Manuscript received 3 April 2020, revised 20 July 2020; accepted 9 September 2020.

APPENDIX A