By Erin Trauth

ABSTRACT

Purpose: This teaching case discusses a community-engaged, service-learning-based, undergraduate introductory technical communication course that employed storytelling as a pedagogical method and a key element in the deliverables produced, including instructional documents for volunteers, program informational brochures for potential volunteers, and a guidebook for a new career readiness construction training program for program participants.

Method: The course, titled “Tiny Houses and Technical Writing” partnered with a local 501(c)3 non-profit organization, Tiny House Community Development (THCD), which builds free tiny homes and offers construction-based career training programs for those experiencing homelessness. We used several techniques to elevate our community partner’s narrative and highlight local issues of homelessness, utilizing storytelling and personas as methods to provide human-centered designs. We also employed technical communication’s emphases on optimal format, arrangement, and style to revise and build documents. The course engaged in project-based service by producing various technical documents as well as providing direct service building tiny homes; this work was often completed alongside clients the THCD organization serves. Ultimately, we aimed to engage the stories of those the organization serves and reflect those stories within the deliverables.

Results: The students in this course ultimately helped THCD streamline communications, increase build productivity, and communicate its mission to the local community. Additionally, the organization used several of our documents in a grant competition and ultimately won $12,000 in future funding. We believe the storytelling element present in the technical documents elevated these communications. The course also sparked several new collaborations, conversations, and publications, thus propelling the organization’s stories—and its human elements—into the larger community.

Conclusion: “Tiny Houses and Technical Writing” serves as an example of a community partnership model for undergraduate introductory technical writing courses and tiny house building groups.

KEYWORDS: technical communication pedagogy, introductory undergraduate technical writing, service-learning, community engagement, tiny houses

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Technical communication courses with storytelling as a pedagogical method to promote human-centered design can help students, community partners, and clients that serve community partners in mutually beneficial ways. A story-based approach to these partnerships allows for students to truly understand the stories of those the organization serves, construct well-informed technical communication personas, and create engaging, human-centered deliverables.

- Instructors of undergraduate introductory technical communication courses should consider partnerships with organizations that would allow students to engage in service acts alongside the clients the organizations serve, extending direct service from a “service to” to a “service with” model that can elevate the course’s service work to an effort that promotes social justice and encourages long-lasting impacts on students’ civic engagement.

- Collaborations can be enhanced if storytelling and narrative are laced throughout the documentation process, from early site visits and meetings to collaborative discussions to the production of final deliverables.

INTRODUCTION

Introductory technical communication courses with a civic and community engagement component, particularly those courses with storytelling as a pedagogical method, have the potential to showcase the range of technical communication programs, encourage interdisciplinary collaboration, grow ethical and critical thinking skills, and serve the local community in positive ways (Andrews, Hull, & Donahue, 2009; Jones, Savage, & Yu, 2014; Walton et al., 2016). In this teaching case, I discuss a Spring 2019 undergraduate technical communication course at High Point University (HPU) titled “Tiny Houses and Technical Writing.” The course helped to 1) teach core genres of technical writing through civic engagement; 2) tell the unique stories of people experiencing homelessness in the Greensboro/High Point, NC, area; and 3) aid a non-profit local organization, Tiny House Community Development (THCD). THCD's mission is to build free tiny homes (typically, homes built to be less than 500 square feet) and provide construction-based career training programs for those experiencing homelessness, thereby rehabilitating lives and providing a sense of community, pride, and accomplishment (Jones, 2019).

The students in this course ultimately helped the THCD organization streamline communications, increase build productivity, and communicate its mission to the local community. Additionally, the organization utilized several of our documents to promote its professionalism and coordination of volunteer efforts in a local grant competition and ultimately won $12,000 in future funding. We believe it was the storytelling element present in the technical documents that elevated these communications. The course also sparked several new collaborations and promotional magazine publications, particularly materials linking the university, the organization, and the local community, thus propelling the organization’s stories—and its human elements—into the larger community. In this teaching case, I will describe this course model with a focus on how it utilized storytelling as a core theme to help students understand the importance of human-centered design in documentation. I will also demonstrate how these stories ultimately helped amplify the organization’s technical deliverables and overall mission.

Tiny Houses and Technical Writing: Course Planning and Background

In Fall 2017, HPU, a private liberal arts university in High Point, NC, launched a new Public and Professional Writing undergraduate minor program in its English department. At first, the program’s focus was on an introductory, 2000-level course titled “Introduction to Public and Professional Writing.” This course was marketed across campus as an orientation to the genres of public and professional writing. At this time, an undergraduate technical writing course had never been offered at the university.

As a new assistant professor at HPU in 2017, I was tasked with promoting the new Public and Professional Writing minor program and leading its future direction. I began teaching the introductory professional writing course and also began looking for community organizations to partner with, specifically with the goal of shaping a new technical writing course around it. I aimed to make the first technical writing course at HPU focused on a collaborative community engagement project to help draw student interest and to present our technical writing course as a potential future space for service-learning projects both now and in potential future iterations. The community engagement lens was also targeted to capitalize on existing program strengths in experiential learning and creative writing as well as emphasize the possibility for technical writing undergraduate courses as a source to promote social justice and access, particularly through storytelling (Walton et al., 2016). Nancy Small (2017) traces the long history of storytelling in technical communication, beginning with a “narrative turn” in the 1990s from the old adage that technical communication “. . . focused on precision, clarity, and conciseness—must not be tainted by any scent of the literary or the aesthetic” (p. 236). Drawing on foundational texts that engage stories as “both data and discourse” (Katz, 1992; Longo, 2000; Winsor, 2003), Small explains that stories can “. . . allow us to analyze organizational identity, organizational discourse, and the persuasive role of shared narratives in forming and influencing the broader company or community” (p. 235).

I understood that utilizing storytelling as a core concept within the new professional writing program might help me to use a shared narrative to make an impact on the broader community, especially in its defining iterations. For new professional, technical, and scientific communication undergraduate programs, it can, at times, be challenging to delineate program aims and explain how the program fits within the university. Interdisciplinary efforts are one way to introduce new programs to other university departments. Still, these collaborations can be difficult to forge for new programs in the earliest stages of defining and establishing themselves within the frameworks of the university. Programmatic and departmental efforts are all competing for university resources and attention, which can further complicate these challenges. With community engagement as a course and programmatic emphasis, new programs can highlight their unique features and become stronger candidates for university resources. Further, such courses can help students grow ethical and critical thinking skills that translate well across disciplinary boundaries, thereby making the larger objectives of the program easier to communicate and connect with other programs and with the university. As an assistant professor trying to introduce a technical writing course into a new writing program to the university, I knew it would be beneficial to build upon ideas of those scholars before me who encouraged both community engagement and storytelling (Jones, 2016).

One community story in particular resonated with me for its match to HPU’s own narrative: a December 2018 video from a local news station featured a new tiny house community program, THCD, serving those who were experiencing homelessness. The first community had broken ground in 2017 and was on track to home its first citizen: a man who formerly experienced homelessness, whom I will provide the pseudonym Peter for the purposes of this article. I learned more about the THCD organization. THCD, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, offers new homes—typically homes of 500 square feet or less—to those in need. Clients are referred to THCD from other local organizations aiding people experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity. The organization serves as a sustainable model of a low-cost, quick-build solution for communities experiencing high levels of homelessness. Most of the organization’s building materials are donated or sponsored by local companies, and other resources are acquired through the support of grants or by individual donations. The organization’s building labor is led by a handful of board members, some of whom are or were contractors, and, every week, volunteer individuals or groups visit the sites and help with the builds. The labor model is similar to what many may know from Habitat for Humanity builds.

The organization’s initial core mission was to help individuals experiencing homelessness with brand-new, low-footprint tiny homes, meant to serve as safe and stable home bases as these individuals work to rebuild their careers and lives. In the summer of 2019, THCD finished its first Greensboro home site, a community of six tiny homes ranging from 180-288 square feet, each with its own bedroom, full bathroom, kitchen with full-size appliances, and living area. The organization showcased plans to break ground on its High Point site, a community of five homes ranging from 384-448 square feet. In the fall of 2019, the organization started on an additional community in Greensboro, with six homes planned at around 504 square feet each. In 2020, THCD broke ground on a High Point community that will specifically aim to house veterans, and the organization now has sites planned or in development in all areas of the greater Triad, including High Point, Greensboro, and Winston-Salem. THCD is also growing a construction career readiness training program, which is offered to a number of its clients living in the tiny house communities. Taught by general contractors and based on the National Center for Construction Education and Research (NCCER) curriculum, the program offers training in a number of in-demand construction trades, allowing THCD program participants a chance to not only live in a new home but learn valuable skills which can translate to a new career in construction.

What really stood out about Peter’s story was the fact that he had helped the organization in the efforts to build his new home. He was part of the career training program, taught by THCD, that focused on teaching construction trade skills to those experiencing homelessness. Peter states in the video:

[The career training program] will help me get back on my feet and start working on my future and clearing some wreckage of my past up. Just start taking care of myself like I’m supposed to. It’s just kind of moving me forward in the right direction.

Peter’s story built on THCD’s narrative that it is an organization that not only serves but also truly helps rehabilitate its clients and empower them with skills to help them help themselves in the future. Peter adds:

There’s definitely a need for people that know how to build houses and whatnot. Now that I have a pretty good idea of how they’re put together and what the process is, it will definitely help me land a job in the future.

The video also features Scott Jones, THCD’s long-standing Executive Director, explaining that when he looks at the six in-progress tiny homes, he does not see “just houses.” Instead, he “sees six lives being changed.”

I considered THCD’s mission to “not just build homes but also build lives” (as stated by Jones, THCD’s Executive Director). Dipadova-Stocks describes how the strongest service-learning outcomes can be achieved when a project is “grounded in the value of human dignity and the inherent innate worth of the individual” (2005), and THCD’s existing messaging was focused on rehabilitation of an individual human life from multiple dimensions: gaining housing security, learning a new trade, and engaging in community work that promoted the idea that all members of a community deserve basic dignities. THCD’s messaging connected to the roots of human-centered design, which focuses on deliverables made with a consideration of human rights, values, and dignity.

As I grew to understand more about this organization and its narrative, I knew THCD would be an ideal community partnership for undergraduate technical writing students at HPU. THCD’s narrative paralleled the existing values of the university, and a potential collaboration seemed ripe with opportunities to practice storytelling and engage in human-centered design. Additionally, the fact that these homes were, in fact, tiny, and therefore able to be built on a decreased build timeline—often taking weeks to build instead of months—would allow for students to see a greater range of the building process within an undergraduate, 16-week semester model.

The idea for “Tiny Houses and Technical Writing” connected my intent for the longer-range story of the HPU Public and Professional Writing program with the High Point’s community needs. I contacted THCD’s Executive Director, Scott, and asked if we could work in “service to” and in “service with” the organization, with a focus primarily on creating human-centered technical documents. He enthusiastically agreed, and in the Spring 2019 term, “Tiny Houses and Technical Writing” commenced with nine undergraduate students, mainly sophomores, enrolled. In the following section, I will provide more details about the course model and the stories we studied as a class.

COURSE DESIGN AND PROJECT OVERVIEW

Building Lives (Not Just Homes): Storytelling, Direct Service, and Human-Centered Design as a Course Frame

In January 2019, “Tiny Houses and Technical Writing” began. The course title, before the inclusion of the service component, was simply “Technical Writing,” a 2000-level course that was advertised to sophomore and junior students interested in an introduction to some of the core genres of technical writing. The students were asked to engage in a layered service-learning approach: engaging both in direct service, in which students work directly with the clients an organization serves, and project-based service, in which students focus primarily on end products for use by an organization to meet its goals (Cress, Collier, & Reitenauer, 2013).

Incorporating the element of direct service through on-site construction training and service model allowed students in the course to develop better informed, more “embodied” (Meloncon, 2017) technical communication personas, which will be described in more detail later in this teaching case.

The students and I discussed the value and advantages of often engaging in direct service alongside the clients themselves. As much as possible, we would purposefully engage with and work alongside members of THCD who were also current or past clients or who had direct experience being rehabilitated and working within the group we sought to serve: those experiencing homelessness. Our subsequent time meeting and working with Mark, who will be discussed later in this section, and Peter, the person showcased in the video described earlier, both served as primary examples of this work. Alongside the advantages this course model would provide in our effort to craft human-centered instructional documents and a career readiness program training guide catered to the unique needs of persons being rehabilitated and homed via THCD’s programs, we would also see benefits from working alongside the program’s clients. Service-learning pedagogy often favors approaches in which students can work alongside partner-served clients, elevating service work that might be viewed as “charity” in a solely “service to” model to a potentially more civic-minded “social justice” approach with “service with” work (Eyler & Giles, 1999; Lorensen, 2014). A “service with” model may also increase the likelihood that students truly understand their own vantage points and develop a longer-lasting desire to continue community work. Service-learning models can help students realize their long-term ability to impact their surrounding social systems (Herzberg, 1994). In a final reflection, a student in the technical writing course wrote:

Our collaboration with THCD really opened my eyes to how privileged most of us really are. We live in a society where we easily take what we have for granted and are continuously wanting more. It was very inspiring to hear Mark’s story and how THCD came about in order to help those experiencing homelessness. Working with them really made me want to appreciate the opportunities I have had and use them to help others.

We also studied unemployment levels and the local housing crisis, seeking to understand the stories of local persons experiencing homelessness as well those who might be teetering dangerously close to homelessness or housing insecurity. Nearly 20% of High Point’s approximately 120,000 citizens live at or below the poverty line—which can seem, for students, a stark contrast to the beauty of HPU’s immaculately landscaped, gated campus (U.S. Census, 2019). HPU is a private university that caters, in large part, to families who can afford (or utilize resources and find a way to afford) a $38,080 per year tuition rate and a $15,438 room and board plan (HPU Tuition, 2020). At $53,518 total for an undergraduate to attend HPU in 2020, the cost of one year at the university is more than double High Point’s per capita income ($26,212 in 2019) and $6,284 greater than High Point’s median household income ($47,234 in 2019) (U.S. Census, 2019). Many HPU students, then, may struggle to understand poverty at a real level, and it was important for the course’s students to gain a greater understanding of the role an engaged HPU citizen should ideally play in the larger community, especially when the university promotes a strong community service-minded narrative in its messaging.

Social justice and service-minded work, of course, connects well with the charges at work in human-centered design models (Jones, 2016). From its inception to the final deliverables, the course used storytelling as a core theme to help students understand the importance of human-centered design in documentation (Jones, 2016). Cardella, Zoltowski, and Oakes (2012) explain that as students focus on the more technical components of document design, they “can not only neglect their users and clients, but also ignore the greater social context and ramifications of their work” (p. 11). Through service-learning work, however, students can develop a stronger understanding of the people impacted by design decisions and the larger “social implications” (p. 11). Technical communication’s roots in human-centered design have, in recent decades, expanded to a human-centered design model (Zachry & Spyridakis, 2016); this interdisciplinary focus on the design experience draws heavily on sociological lenses, moving the focus from the user experience to a more holistic and humanistic design: one which places a greater significance on human values and dignity. Linking our course’s service work to the human stories of people experiencing homelessness and being rehabilitated through community support as well as a place to call home, often at least partially by the work of their own labor, allowed me to emphasize to the HPU students that our final deliverables should incorporate those human values. Specific final deliverables included client narratives, images, and histories being added throughout otherwise primarily text-based instructional and guidance documents.

Initial Research, Client Meetings, and Direct Service

Our course partnership with THCD began with extensive background research into the organization, its programs, and its people. Before any sort of client or on-site meeting, we spent nearly two weeks of course time watching videos, exploring social media posts, and reading previous news coverage on the organization. I shared Peter’s story—the story which enticed me to work with the organization in the first place, and we also intently studied Mark’s story. Mark, who served as the Tiny House Community Development Construction Committee Chair and organization board member, was an instrumental part of THCD and a person who embodied the THCD mission and values. Despite this, Mark’s incredible story was not as apparent on THCD’s program documents, its web site, or social media posts at that time; by the end of our semester partnership, the HPU students found multiple ways, including snippets of his story in new program brochures, instructional documents, and a career readiness program guidebook, to tell his life’s narrative as a thread which laced through many parts of the documentation process.

Mark emphasized the narrative that the THCD organization sought not just to build homes, but to build lives: and that his story was a lived example of this model. We had studied him using all the data points we could from online sources beforehand, but he truly captivated the room of students when he delivered his message in person: with a fierce alcohol addiction, Mark drank every day since the year 2000, sometimes having to drink a 40-ounce beer just to stop shaking when he woke up and to start his day. For 12 full years, Mark experienced homelessness and lived in a tent in the woods. He panhandled during the day for enough money to buy more alcohol. One day, in 2012, he returned to his tent after having made enough money throughout the day to purchase four 40-ounce beers and found his tent cut to pieces and his few belongings strewn about the woods. At that moment, Mark decided he needed to make a change in his life, and, serendipitously, some volunteers showed up in the woods, seeking to help the people experiencing homelessness living in that area. Mark then was taken to a hospital and entered into a rehabilitation program and began attending church. It was through church that Mark met Scott Jones, who was already at work building a new non-profit organization that would build tiny homes for those experiencing homelessness. Mark, despite having no construction experience, then became involved with THCD; he learned, day-by-day, how to construct tiny homes through his volunteerism. In many ways, although the component of the THCD program did not yet exist, Mark was THCD’s first career readiness program participant, learning a trade and finding community around him which would eventually take him from being a hopeless, alcoholic man who lived in a tent for 12 years, to a sober man with a safe roof over his head, a member of THCD board, a volunteer trainer, and a small business owner. It was this personal empowerment model that Mark had himself experienced, inspiring the students to make deliverables that helped others get work done but also captured the powerful narratives at work within the THCD organization and placed these human stories at the center of focus.

After Scott and Mark’s first visit to our class, I was met with a line of students after class, all telling me some version of “I cannot wait to help this organization!” The THCD story had been made concrete in the minds of my students, lighting a fire in them to aid the organization with its technical communication documents and help it to fulfill its larger mission. Without Mark’s engaging storytelling, I am not convinced I would have seen that same level of student buy-in to the course model, especially considering the intensity of the service I was asking students to complete. I am no stranger to service-learning courses, having guided students over the years in a number of other service-learning course projects, and I saw excitement and an initial desire to serve that I had not witnessed before. One student in the class, a sophomore pre-law student with a professional writing minor, said:

I really appreciated hearing Mark’s story because it made us realize that the THCD organization helps change lives. When he told us his story, we understood that the program could really work, and that made me buy-in to what we were doing as a class much more than other service-learning projects where I was not sure about my long-term impact or if the program truly worked.

Mark’s story—and the ethos he brought to our learning situation—continued in our visits to the client site. During one visit, we were invited to help frame a tiny home wall using a powerful construction-grade nail gun. The students were timid, some outwardly expressing apprehension with their body language, physically turning their bodies away from the gun. Mark, already a guiding presence in our class, helped alleviate these apprehensions by reminding the students, again, that he had started with no prior use of a nail gun, but now he felt comfortable shooting them all day long: “I didn’t know anything about these guns before, and now these guys put me in charge of shooting this thing all day, every day!” he exclaimed. Every student took at least a few turns shooting the nail gun that day, and quotes like these were able to be utilized in instructional documents for volunteers new to using a nail gun. It was Mark’s story, injected onto the pages after experiences like these, working with the HPU students, that made these considerations possible, and made our final documents more human-centered. For the rest of the visit, the HPU students worked to frame a tiny house wall with Peter, who formerly experienced homelessness and was being served by the THCD program. These embodied, lived stories—these human interactions shared while learning and building and the verbal quips that went along with them—helped bring this partnership, and the human-centered considerations we were living through on-site experiences to life for the HPU students—even when we were, at a later time, writing documents on the HPU campus, far removed from the muddy job site. These stories, shared between people like Mark and the HPU students, helped motivate and inspire the ultimate quality of the class deliverables. As Matthews and Zimmerman (1999) write on the integration of service learning and technical communication, such experiences help students to become “motivated to accept responsibility for their own education because their communication matters—it has direct results in other people’s lives” (p. 386).

Over time, we eventually narrowed in on THCD’s greatest immediate documentation needs. Based on their interests, the students were eventually split into core teams, with at least one major technical document as each team’s focus, including instructional documents and brochures as well as a career readiness program guidebook. In the following sections, I provide further detail on these documents as well as how storytelling was intentionally injected into each deliverable throughout the design or redesign process.

Deliverable Examples: Instructional Documents and Brochures

One course assignment tasked students with creating tiny home instructional documents for building volunteers. To supplement these guides, the students added personalization and generated enhanced buy-in for the building volunteers through short snippets and quotes from stories of those persons experiencing homelessness who benefit from the tiny homes, as well as brief histories of the various programs. A short instructional document on how to don the proper personal protective equipment (PPE) on the THCD job site, for example, did not only include guidance. The document also included the name, brief story snippet, and image of one of the people living in a THCD home in proper PPE at work building a tiny home frame and dressed in the appropriate hard-toed safety boots, clear goggles, and hard-top head covering.

Scott, THCD’s Executive Director, explained to the HPU students why it was so important to engage in storytelling in the technical documents:

We get a range of volunteers at THCD, from individuals to corporate volunteers to civic and religious volunteers. Many of them come to volunteer with us with an initial interest in the ‘tiny home’ part of it—they come interested in learning how to build these homes they have seen all over HGTV. But once they get to know our story—and the stories of those we are serving—the volunteers discover so much more about the program, and their personal takeaway is so much greater. They even learn more from knowing these stories: they come in with no technical construction skills, but they leave our sites with new skills, becoming more comfortable and having the confidence to try to repair something or start a DIY project in their own homes. Most importantly, they also gain new perspectives and learn about people experiencing homelessness in the areas we live in, and by learning these stories through these documents and while they work on-site or while serving hot meals, they gain so much more from the experience beyond just working on a tiny house.

Deliverable Examples: Career Readiness Program Training Guide

Another team in the class primarily designed and edited a training manual for THCD’s Construction career readiness Training program, which allows people experiencing homelessness to live in tiny homes while enrolled in an in-house construction trade training program. The Construction Readiness Training program is an initiative by THCD to not only provide housing for its clients but also provide a chance to build a new career in construction. Taught by licensed general contractors and centered on the National Center for Construction Education and Research (NCCER) curriculum, the program’s focus aims to serve those who have faced barriers to employment and provides hands-on training in construction planning and math, blueprints, power and hand tools, and build sustainability training. Additionally, program participants can receive certifications in the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Most participants graduate with a letter of recommendation and a certificate of completion. Mark explained that his THCD-led construction training helped him feel “from homeless to human again,” and the students then used this as one core story thread throughout the subsequent deliverables, employing this phrasing in section headers and throughout the guidebook, intending to provide its users with a story they could use as motivation and inspiration when studying complex construction topics in the program.

In what would have otherwise been primarily a text-based training guide to accompany the career readiness program and to promote its availability, the HPU students also opted to provide a full THCD program history in the guide. Images from builds and past volunteer groups were also added throughout the guide, providing visuals to the THCD narrative and history, and thereby giving a “face to the name” of those involved in this organization’s development. All of these elements were added with the goal of increasing the overall emotional impacts on the guide’s users and linking members of the career readiness program with a larger narrative of community connection and support. With Mark’s personal story in mind, we discussed the idea that those who already face employment barriers might need increased support and need to know the community around them supports their endeavors to rejoin the workforce. One student cited Mark’s personal story of how he lived in a tent for 12 years and made the first step to rehabilitate his life when his tent was destroyed but also when a group reached out to him directly and asked if they could take him to the hospital, thereby beginning Mark’s rehabilitation and path to a new life. The HPU student posited, then, that we should include many more visuals of community members at the THCD building sites and at Breakfast 4 Our Friends events, making it clear to members of the career readiness program through a visual argument that they had the support of so many people living around them and thereby encouraging them to stay the course through the more difficult parts of the training. Students requested images from the THCD team, and we chose to include images that showed large groups of people at work on the job sites to elicit this community support idea. Figure 1 below shows one of the images the students chose to include within the career readiness program guidebook. Of the many images available, students chose this example photo because it showed a range of build volunteers, representative of the diversity in ages, races, ethnicities, and abilities in our local community: Those in the photo were behind the build and, in the students’ words, also “behind the THCD program participants.”

Across All Deliverables: Core Concepts and Strategies of Technical Communication in Practice: Organizational Elements, Simplification, and Personas

Across All Deliverables: Core Concepts and Strategies of Technical Communication in Practice: Organizational Elements, Simplification, and Personas

Many of the aforementioned instructional documents, program brochures, and guides were made from existing longer documents—typically pages of typed notes pulled from a variety of sources, some featuring complex technical construction jargon from the National Center for Construction Education and Research (NCCER) curriculum or early prototypes of brochures made on Word document templates with informal, simplified language and personal quotes. As a class, we engaged in some document redesign. In particular, we employed technical communication’s emphases on optimal format, arrangement, and style, including, in particular:

- Chunking information,

- Prioritizing the order of sections,

- Highlighting of core sections through headings and subheadings,

- Constructing purposeful redundancies to enhance reader recall, and

- Simplifying complex jargon whenever possible.

We were also able to intently consider issues of context and contexts of use, for example, suggesting that THCD not just bind documents in a weatherproof binder but also laminate certain key instructional documents that might be taken out of the binder for use on its job sites, anticipating various weather and use conditions.

Another useful component of this partnership was that the construction of tiny homes themselves served as a fitting metaphor for how to construct human-centered documents: when one builds a tiny home, they are limited by a specific footprint, and no space can be wasted. The essentials must be thoughtful and purposefully fit into a tight space, and only the most important components can be included in the final product. At the same time, filling the tiny home with all that is needed to live, we do not want to crowd: this is a space we want to be aesthetically pleasing and rich with thoughtful design. We made an effort to leave white space for breathing room when possible, grouping like items, adding repetitive elements that tie the whole home together, and, in the end, making a visual impact that feels clean, inviting, and human-centered.

Personas and New Content

Our partnership with THCD also allowed for the use of more informed technical communication personas. As discussed earlier in this teaching case, the students were asked to engage in a layered service-learning approach: engaging both in direct service and project-based, which allowed for more informed persona development. Quality personas, which serve as depictions of real document users, depend on optimal “user data that underlies them, that is, the research that studies the ways in which users interact with an interface, product, or system” (Brumberger & Lauer, 2020). Used thoughtfully, personas can help document designers keep in mind that they are designing for real users with varying goals, motivations, contexts, skill levels, frustrations, and challenges (Mears, 2013). In their strongest iterations, personas will have layered, “embodied dimensions,” including considerations of culture, bodily ability, and emotions (Meloncon, 2017), all in the context of increasingly mobile people using mobile devices for a number of worksite tasks. Because of our focus on learning the stories of those served by the THCD organization, and by building parts of tiny homes alongside some of them, the HPU students in the technical writing course were able to get to know these people as multi-dimensional, complex beings, seeing a range of abilities and emotions and cultural differences along the way. We not only observed the program participants and build volunteers at work in building tiny homes, but by using the “service with” model of service learning, we worked alongside them. As a class, we are able to then reference more realistic personas of both the THCD program participants and the volunteers who might come out to the THCD job sites for the first time with limited or no construction experience. It was especially helpful in this case because many of the volunteers who help THCD come from college groups or ministries and have minimal to no construction experience. So the volunteer personas, along with the attributes, concerns, and questions these named personas might have were often in-line with those from our own student demographics and construction ability levels.

Our first class visit to a job site, in which the HPU students were taught to effectively don personal protective equipment and use a powerful construction-grade nail gun to frame a tiny house wall, for example, served as an optimal experience for students when they constructed a persona for their own instructional documents. For this reason, I asked students to bring a notebook to the first visit and record the thoughts, fears, apprehensions, and questions they were having as immediately as they could. They were instructed to make special note of the physical and emotional requirements involved in using a nail gun: what physical abilities does this action require? Who might be limited from completing this task because of a potential disability? What emotions might someone feel using a powerful nail gun (that, if used incorrectly, can seriously injure one’s body in an instant)? We considered issues of mobility and movement on a job site: would it necessarily be best to create instructional documents that would be viewed digitally on a mobile device? Or, given issues of access and equity (especially for those in the THCD program who might not have a mobile device) and context (e.g., would it be easier to have laminated hard-copy documents that could be bound to clipboards so as to make them hands-free for use when using a power tool?). We downloaded all of our thoughts together during our next class meeting, writing out notes together on a shared whiteboard space and discussing our first impressions and major questions about these construction processes. By doing this, we were able to make personas based on real data points, aiding in our use of this technical communication technique in designing human-centered documents.

When working on the career readiness training program guide, it was also incredibly helpful for us to have been able to meet and learn the stories of some of the persons experiencing homelessness before and during our writing and designing period. We assigned names, key attributes, and informational/contextual needs for several sample personas. By getting to know our audiences through the stories of real people, we moved beyond demographics, statistics, and the stereotypes about people experiencing homelessness and job loss, putting names to our potential audiences and trying, at a deeper level, to help construct technical documents that met their unique concerns, work situations, and human needs. Moreover, by learning the unique stories and needs of people facing unemployment and homelessness and working side-by-side with people such as Mark (who had learned construction skills on THCD job sites, rehabilitated his life, and created a new path and role on the THCD board), we were able to construct personas of others who might be interested in working with and being served by the THCD program.

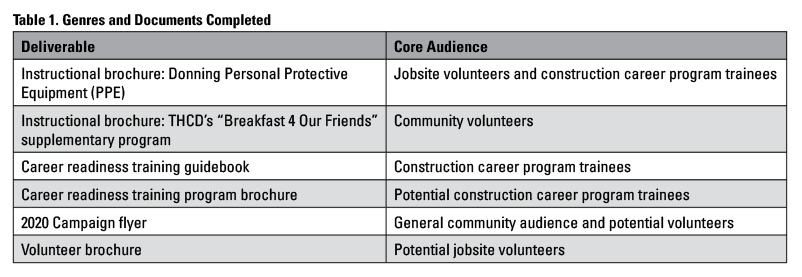

In addition to the more technical instructional documents and the career readiness guidebook, the class worked to create several new documents for use by the organization, including brand new volunteer brochures and a flyer explaining the organization’s “2020 campaign,” an initiative to build at least 20 new tiny homes across the Triad through the year 2020. In total, the class delivered six new technical and professional documents to the organization by the end of the term, resulting in a number of outcomes for students, the organization, and the course’s role as part of the greater story in the HPU community. Table 1 below summarizes the genres and documents completed as a result of this partnership.

DISCUSSION

At the end of the semester, the documents created in “Tiny Houses and Technical Writing” were used throughout the organization including on social media, on the organization’s web page, and on job sites for volunteer use. The documents were also used to promote the career readiness training program. Additionally, in April 2019, THCD competed in a local grant competition, Future Fund 10, and used many of the class documents at its booths to help professionalize and promote the program’s mission. THCD ended up placing second in the competition, winning a $12,000 grant from Future Fund 10 to grow its programs, particularly the career readiness training program for which we helped create a guide.

Additionally, the course became an opportunity to tell HPU’s story, as I was asked to write an article about the course for HPU’s university magazine. Titled “Tiny Houses and Technical Writing: A Unique Learning and Community Service Opportunity,” the magazine article served as a fitting bookend to the project, especially considering that THCD was initially selected for the partnership in part because of the belief that it would resonate with HPU’s core audiences.

Finally, the course allowed me, a relatively new assistant professor promoting a new program within the broader university community, to tell a story in various spaces on campus about some of the new Public and Professional Writing minor’s aims, one of which would focus on creating civic-minded, human-centered communicators. Through the course and the article, I debuted the course and the new program to the university with a specific lens that can shape its future.

The students in HPU’s “Tiny Houses and Technical Writing” course ultimately helped the THCD organization streamline communications, increase build productivity, and communicate its narrative to the local community. The course’s focus on “service with” clients the partnering organization assists—as well as its emphasis on human-centered design enacted by storytelling—led to positive outcomes for the students, the THCD organization, and the partnership’s deliverables. The course also propelled the organization’s stories—and the many people THCD services—into the larger community, therefore guiding and inspiring future volunteers for years to come.

It can, of course, be difficult to replicate these same outcomes in a new semester, even if we were to partner with the same organization. It can be even more difficult to forge the same sort of partnerships at other institutions, especially with different student body values and varying foci of community organizations. However, it is my assertion that most any organization building tiny homes in a non-profit, community-engaged capacity, could potentially serve as a fruitful partner for technical writing courses. These organizations are popping up all over the world and in the United States, serving a range of community members, including those experiencing homelessness, veterans, teenage parents, persons fleeing abusive home situations, and more—for example, Community First! Village in Austin, TX, houses 180 residents who formerly experienced homelessness in 200-square-foot tiny homes over a plot of more than 50 acres; its residents can work on-site and farm much of their own food in a community garden. Similar communities are planned, in progress, or have been built in cities such as Detroit, MI; Syracuse, NY; Nashville, TN; Seattle, WA; Los Angeles, CA; Newfield, NY; Dallas, Texas; Olympia, WA; and Portland, OR (Curbed, 2016).

The core nature of the work of these organizations—building homes and helping community members—in itself is a natural partnership for the genres of documentation for an introductory undergraduate technical writing course. The complex nature of construction—and teaching construction processes to volunteer workers—requires acute attention to user needs, and students in the course practiced these skills. One HPU student in the course, who plans to become an adolescent psychologist, wrote in her course reflection:

This collaboration and my experiences working with a client can potentially help me as a psychologist in the future since I will be working with patients. In this field, it is essential to focus on the needs of the specific patient. It was a huge learning experience getting to create THCD documents based on the clients’ needs and then revising them after receiving feedback. It requires you to learn how to put your own thoughts and opinions aside and focus on what is best for the client.

When a university service course can focus on human stories as a pedagogical framework and also help the partnering organization build a narrative that will propel it into the community in deeper ways—in this case, helping the university professional writing program make a name for itself within the university community and helping the organization gain new volunteers and grow its resources and programs through enhanced notoriety, the ground is set for a meaningful, productive relationship. Furthermore, many of the values set forth by non-profit tiny house organizations align with university calls for pedagogies that instill student resilience and growth mindsets. Students also have the opportunity to learn from the stories of the clients these organizations serve; opportunities abound to utilize stories as pedagogical frameworks and include narratives as part of the technical deliverables designed and constructed. These partnerships also allow students to see firsthand the potential impact of technical communication deliverables within an organization, connecting course assignments with real-world efforts and goals which serve a community effort (Jones, 2016; Cardella, Zoltowski, & Oakes, 2012). For all of these reasons, I encourage undergraduate technical writing instructors to consider partnerships with organizations engaging in housing efforts—particularly on the tiny scale—thus aiding student outcomes, organizations, and the clients they serve. In sum, this topic:

- engages the interests of the current generation of undergraduate students;

- suits introductory technical writing genres (particularly instructional documents; informational brochures, and guidebooks),

- allows for the employment of human-centered design through storytelling, promoting meaningful community engagement and partnerships;

- aids volunteers in their ability to assist with a complex construction project;

- and serves the needs of community members experiencing homelessness who might benefit from the improvement, growth, and promotion of such programs.

Additionally, several of the lessons learned from this teaching case can potentially be applied to partnerships with organizations serving any number of community groups. Most any organization with people at its core can use technical communication documents to document processes, tell organizational stories, and advance its community mission. University technical communication courses seeking service work with community organizations can heed the notion that the collaboration will be enhanced if storytelling and narrative are laced throughout the documentation process, from early site visits and meetings to in-class discussions to the production of final deliverables.

REFERENCES

Andrews, D. H., Hull, T.D., & Donahue, J.A. (2009). Storytelling as an instructional method: Descriptions and research questions. The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning, 3(2), 6–23.

Barton, B. F., & Barton, M. S. (1988). Narration in technical communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 2(1), 36–48.

Brumberger, E., & Lauer, C. (2020). A day in the life: Personas of professional communicators at work. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 50(3), 308–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281619868723

Cardella, M. E., Zoltowski, C. B., & Oakes, W. C. (2012). Developing human-centered design practices and perspectives through service learning. In Baillie, C., Pawley, A., Riley, D. M. (Eds.), Engineering and social justice: In the university and beyond, (pp. 11-30). Purdue University Press.

Cress, C.M., Collier, P. J., & Reitenauer, V. L. (2013). Learning through serving: A student guidebook for service-learning and civic engagement across academic disciplines and cultural communities (2nd edition). Stylus.

Dipadova-Stocks, L. N. (2005). Two major concerns about service-learning: What if we don’t do it? And what if we do? Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(3), 345–353.

Eyler, J. & Giles Jr., D. E. (1999). Where’s the learning in service-learning? Jossey-Bass.

Facts About Homelessness. (2021, February). Interactive Resource Center. https://interactiveresourcecenter.org/donate/facts-about-homelessness/

Herzberg, Bruce. (1994). Community Service and Critical Teaching. College Composition and Communication 45, 307–19.

High Point, North Carolina: Population (2019). United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/highpointcitynorthcarolina

Jones, N., Savage, G., & Yu, H. (2014). Tracking our progress: Diversity in technical and professional programs. Programmatic Perspectives, 6(1), 132–152.

Jones, N. N. (2016). Narrative inquiry in human-centered design. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(4), 471–492.

Jones, S. (2019). Tiny House Community Development: Program mission and goals. https://www.tinyhousesgreensboro.com/

Katz, S. B. (1992). The ethic of expediency: Classical rhetoric, technology, and the Holocaust. College English, 54(3), 255–275.

Ladd, S. (2017). Housing Summit showcases challenges and achievements. News & Record. https://greensboro.com/blogs/around_town/susan-ladd-housing-summit-showcases-c hallenges-and-achievements/article_f5aecdc2-a8aa-51ce-9b06-5074d42d7db2.html

Longo, B. (2000). Spurious coin: A history of science, management, and technical writing. State University of New York Press

Lorensen, M. (2014). Telling our service-learning story: Instructor perspectives on service-learning in the leadership classroom. theses, dissertations, & student scholarship. Agricultural Leadership, Education & Communication Department. 100. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/aglecdiss/100

Matthews, C. & Zimmerman, B. B. (1999). Integrating service learning and technical communication: Benefits and challenges. Technical Communication Quarterly, 8(4), 383–404. doi: 10.1080/10572259909364676

Mears, C. (2013). Personas—The beginner’s guide. theUXreview. https://theuxreview.co.uk/personas-the-beginners-guide/

Meloncon, L. (2017). Embodied personas for a mobile world. Technical Communication, 64(1), 50–65.

Peterson, C. (2018, December 23). Tiny homes make a safe place for the homeless [Video]. Spectrum News 1. https://spectrumlocalnews.com/nc/triad/news/2018/12/23/homeless-man-helps-build-tiny-homes-to-live-in-and-build-a-future

Small, N. (2017). (Re)Kindle: On the value of storytelling to technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 47(2), 234–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281617692069

Tuition & Fees. (2021, February). High Point University. http://www.highpoint.edu/admissions/tuition-fees/

Walton, R., Colton, J., Gurko, K., & Wheatley-Boxx, R. (2016). Social Justice across the curriculum: Research-based course design. Programmatic Perspectives, 8(2), 119–141.

Widner, C. (2016). Tiny houses in Austin are helping the Homeless, but it still takes a village. Austin Curbed.

Winsor, D. A. (2003). Writing power: Communication in an engineering center. State University of New York Press.

Xie, J. (2017). Ten tiny house villages for homeless residents across the U.S. https://archive.curbed.com/maps/tiny-houses-for-the-homeless-villages

Zachry, M., & Spyridakis, J. H. (2016). Human-centered design and the field of technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(4), 392–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616653497

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Erin Trauth, PhD, is an assistant professor of English (professional and technical writing) at High Point University. She serves as an assistant editor for Rhetoric of Health and Medicine. Her work has appeared in Community Literacy Journal, the American Medical Writers Association Journal, the Routledge Handbook of Vegan Studies, the Rhetorical Construction of Veganism and Vegetarianism, and the International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development.