By Erin Brock Carlson and Martina Angela Caretta

ABSTRACT

Purpose: The aim of this article is to demonstrate that rural landowners and community members’ place-based, situated knowledge is expertise that should be taken into account by TPC professionals involved with technological or environmental development (e.g., in the energy sector).

Method: This paper is grounded in the stories of 31 residents of rural West Virginia who share concerns about ongoing natural gas pipeline development. Through visual and place-based storytelling methods, walk-along interviews (Carpiano, 2009) and photovoice (Sullivan, 2017), a rich collection of stories and photographs that reveal the often-undocumented effects of pipeline development were gathered.

Results: The stories of residents living in close proximity to natural gas pipelines reveal two main types of knowledge circulating in conversations about energy development: knowledge rooted in more traditional forms of epistemic authority, such as legal definitions and technical accounts of land; and situated knowledge derived from lived experiences of people directly impacted by technological and environmental changes.

Conclusion: Ultimately, we argue that to embrace stories told by rural residents is to center the experiences of communities, which, in turn, legitimizes situated knowledge resulting from first-hand experience. This demonstrates that expertise can be located in spaces outside of corporate, technical, or academic knowledge, and encourages technical communicators to seek out that expertise in their own work.

KEYWORDS: Environmental Risk, Gas Pipeline Development, Appalachia, Photovoice, Storytelling

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Landowners and community members possess valuable situated knowledge of their surroundings that cannot be easily captured by technical or legal definitions of problems.

- Insights from landowners must be gathered when technological or industrial advancements bring heightened levels of environmental risk.

- Research methods based in storytelling, including visual and participatory approaches, can be a way to access place-based, situated knowledge.

INTRODUCTION

Rural communities are often overlooked because of their remote locations and small populations, even though they are often sites of industrial development that provide amenities for urban and suburban areas. For example, more than two million miles of natural gas pipelines run throughout the United States, many of which are constructed through sparsely populated areas (Office of Pipeline Safety, 2021). Rural areas in the Appalachian region have seen a boom in pipeline development in recent years with construction of the Atlantic Coast and Mountain Valley pipelines. West Virginia alone has seen a four-fold increase in natural gas production in the last decade (U.S. Energy Information Administration [EIA], 2021), making it a likely site for continued development.

West Virginia has a complex history with extractive industries, most notably, coal mining. Though coal has been largely replaced with hydraulic fracturing and natural gas pipelines, the dominance of extractive industries has remained largely unchallenged because of presumed economic necessity and a deeply rooted cultural nostalgia for coal, which are inextricably linked (Bell & York, 2010; Kurlinkus & Kurlinkus, 2018). The presence of extractive industries, however, comes with risks to places and people alike. Rural communities at the forefront of natural gas pipeline development and accompanying buildout face these risks daily; however, their concerns often go unacknowledged by industry representatives. Further, landowners are often not consulted until late in the development process (Finewood & Stroup, 2012). This results in tension between many rural residents and the natural gas industry, because residents feel like they have very little voice in plans for pipelines—a tension reminiscent of other studies of environmental policy’s impact on rural communities (Simmons, 2007).

Recent work urges technical and professional communication (TPC) professionals to seek out and amplify the stories of people who have been overlooked, ignored, or even silenced (Haas & Eble, 2018; Walton, Moore, & Jones, 2019). Rural West Virginians impacted by the development of natural gas pipelines are one such group that can tell stories about how energy infrastructure can drastically change natural environments, increasing perceptions of environmental risk. While many official narratives about natural gas pipeline development in West Virginia tend to focus on economic opportunities offered to rural communities by the industry (Willow & Wylie, 2014), the everyday realities of living in the shadow of industrial development often go unconsidered. Natural gas pipelines constructed in close proximity to rural communities heighten levels of perceived environmental risk, as landowners in this study reported fears of explosions, water and ground contamination, and air pollution; however, they also reported that their fears were rarely attended to. As Simmons (2007) points out, models of risk assessment and management are often “arhetorical—typically decontextualizing risks [and] failing to consider the knowledge local citizens can contribute” (p. 1); as a result, residents’ first-hand knowledge of their land is often not viewed as valuable information, even though they arguably know the landscapes surrounding their home better than anyone else.

This article argues that rural residents’ situated, place-based knowledge is expertise—expertise that should be valued by decision-makers when environmental changes (and therefore, risks) are on the horizon. Stories emerging from residents living in the wake of technological-environmental development are a manifestation of situated knowledge that TPC professionals should not only acknowledge, but amplify, because they demonstrate how place factors into such scenarios. The findings in this article are built upon stories from 31 residents in rural West Virginia concerned about ongoing natural gas pipeline development. We engaged visual and place-based storytelling methods—walk-along interviews (Carpiano, 2009) and photovoice or participant-generated imagery (Sullivan, 2017)—that resulted in a collection of stories and photographs documenting often unpublicized effects of pipeline development.

Given that “when we think of experts, we often do not think of vulnerable populations” (Rose, 2016, p. 442), rural residents’ situated knowledge might not initially be seen as expertise, as decision-makers default to industry and legal experts. However, the stories in this article present a nuanced picture of the relationship between residents’ situated knowledge and industry’s presumed epistemic authority, offering “a more adequate, richer, better account of a world” (Haraway, 1990, p. 187). Our approach is rooted in feminist epistemologies that challenge the notion of objectivity (Haraway, 1990), accepting that all knowledge is socially constructed. “Situated knowledge” emphasizes the importance of lived experiences in how knowledge is created, codified, and valued; put more simply, all knowledge is dependent upon the situations, experiences, and places it emerges from. So, drawing on Haraway and other poststructuralists from the late 20th century, we contend that there are multiple accounts (or knowledges) of any phenomenon. As a result, TPC professionals must be careful not to dismiss any account based on a supposedly objective preconceived notion of expertise. Rather, when working in contexts related to environmental change, we urge TPC professionals to consider the many factors that shape knowledge, including place.

In this article, we position place as an entry point into this understanding, deploying storytelling as methodology (Powell et al., 2014) and using specific research methods of photovoice and walk-along interviews to illuminate the relationship between situated knowledges and accounts of environmental risk. To start, we lay out the background of natural gas pipeline development in the Appalachian region, specifically West Virginia. We then offer an overview of how TPC has discussed environmental risk, and how stories from rural residents might be a valuable intervention in those discussions. After outlining study methods, we share results that highlight the forms of technical knowledge that dominate conversations about pipeline development, and then complicate those forms by discussing the types of situated, place-based knowledge that rural residents possess. Findings suggest that stories from residents about natural gas pipeline development illuminate the realities of environmental risk—realities often rendered invisible by more powerful institutions whose epistemic authority shapes dominant narratives. Awareness of these stories and their accompanying insights are integral for TPC professionals working on projects related to energy development and more broadly, projects that might bring about heightened levels of environmental risk. Ultimately, we argue that to embrace stories told by rural residents is to center the experiences of communities, which, in turn, legitimizes situated knowledge resulting from first-hand experience, demonstrating that expertise can be located in spaces outside of corporate, technical, or academic authority.

NATURAL GAS PIPELINE DEVELOPMENT IN RURAL APPALACHIA

The Appalachian region has long been a site of energy extraction. Coal has historically been the centerpiece of the energy industry in the region, but the dominance of the coal industry is in decline (Gruenspecht, 2019). Hydraulic fracturing and natural gas pipelines are the new face of extractive industries in the region. Advancements in extraction technologies have made the Marcellus Shale, which encompasses all of West Virginia, a crucial source of energy for the United States. West Virginia has the fourth-largest natural gas reserves of any state despite its small size, making it the nation’s sixth-largest producer of marketed natural gas in 2019 alone (EIA, 2021) and positioning it as a key contributor to the energy landscape of the United States.

Proponents of the industry cite economic expansion as a major outcome of this natural gas boom in the state; however, the impacts on West Virginian communities vary (Emanuel, Caretta, Rivers, & Vasudevan, forthcoming). Ironically, despite massive amounts of natural gas emerging from West Virginia, in 2019, 91% of West Virginia’s electricity was generated in coal-powered plants (EIA, 2021). This statistic indicates an uneven distribution of resources—and by extension, wealth—where communities rarely use the natural resources extracted just miles from their homes, as gas is exported beyond state borders. Additionally, because natural gas construction often occurs in rural areas with varying incomes, many residents can’t afford to pay for their own gas line hook-ups or appliances (e.g., gas ranges, heaters, and the like). Further, and perhaps most importantly, buildout of extractive infrastructure, which includes pipelines, gas wells, processing plants, storage hubs, and petrochemical facilities, has negatively impacted communities around the region. In addition to shifts in water quality (Brantley et al., 2014) and water security (Turley & Caretta, 2020), communities have experienced changes in natural ecosystems (Buchanan et al., 2017) and live with fears of explosions, pollution, and other disasters (Bugden & Stedman, 2019).

Fenceline communities—communities located in close proximity to industrial infrastructure and therefore witness to its effects—are disproportionately inhabited by disenfranchised populations, including communities of color and the working class (Fleischman & Franklin, 2017). This reality contributes to a dearth of attention placed upon the lived experiences of communities, especially rural communities that experience the repercussions of, for example, industrialized livestock operations (Wing & Johnston, 2014), the relocation of coal ash (Eldridge, 2018), and natural gas pipelines and accompanying industrial infrastructure (Johnston, Chau, Franklin, & Cushing, 2020).

USING STORIES TO CONTEXTUALIZE ENVIRONMENTAL RISK IN TECHNICAL AND PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION

Communities living in the shadow of industrial development have situated knowledges rooted in their perceptions of environmental risk that often emerge through stories about place. Place, despite its ubiquity, has not historically been a pronounced focus within TPC. In 2019, Ross, Oppegaard, and Willerton argued for further work under the guide of a “place-based ethic” that “encourages technical communicators to be more aware of the people and places involved with and affected by a particular technology” and includes “actively acknowledging the environment’s value” and “seeking dialogue among involved parties” (p. 5). To do so is to re-imagine the relationship between “technical communicator, interlocutor, and place as new stakes such as wellbeing and survival are considered” (Aguilar, 2020, p. 7). Pinpointing place as a central component of technical communication offers opportunities to engage previously unacknowledged understandings of complex problems.

Place serves as an anchor for shared community perceptions, including environmental risk. TPC has engaged environmental risk from a variety of vantage points, including the role of documentation in public perceptions of environmental change (Tillery, 2003; Youngblood, 2012), as well as how public discourse could more effectively engage citizens (Lindeman, 2013; Simmons & Grabill, 2007). When ecosystems are disrupted by environmental changes, resident perceptions of risk are often heightened, given the uncertainties that such changes bring. Frost (2018) explains that the lived histories of those at-risk directly shape perceptions of risk; however, “. . .minority or marginalized publics who may have different perceptions of risk than the often-assumed ‘standard’ public based on historical inquiry are often not taken into account” (p. 25). Institutional accounts of risk differ from lived experiences of vulnerable community members that face such risks each day (Pflugfelder, 2019), which contributes to a gap between decisionmakers and residents.

To address this gap, technical communicators might juxtapose multiple accounts of risk in the midst of environmental changes, like those brought on by natural gas pipeline development. In their study examining how farmers and scientists discuss cellulosic biofuels, Herndl et al. (2018) note that scientists talked in the abstract while farmers spoke in specifics, talking “about farms where they lived and worked” (p. 69). While they note the complexity of integrating these two perspectives, Herndl et al. call for more attention to be placed on how these perspectives emerge in local settings (p. 89). Others also point to the value of local contexts, which illuminate the connections between personal stories and empirical data (Sackey, 2019); provide opportunities for multiple accounts of problems and associated risks (Moore, 2017b); and privilege “the perspectives of local users and communities that should be driving the discussion” (Legg & Strantz, 2021, p. 67). Community-based understandings of risk, change, and environment must be not merely acknowledged, but seen as foundational in public conversations about technological development and resulting environmental changes. Energy development is a particularly poignant setting to examine community-based understandings of risk and environmental change, and has received attention in TPC (Eichberger, 2019; George, 2019). As Ballentine (2019) notes, constructions of risk are central to conversations about energy development and factor into landowner’s decision-making processes. Ultimately, perceptions of risk are place-based, situated in knowledge held by particular individuals and communities.

A localized notion of risk requires us to examine our ontological approach to knowledge and where we locate epistemic authority. Epistemic authority is endowed to those that are assumed to be in the position of the “knower,” be it a scholar or a presumed “expert” rooted in another form of technical knowledge. The privilege of holding such assumed expertise is typically given to those that possess educational or job titles aligned with the issue at stake (Fricker, 2007). In this study, these presumed experts are oil and gas industry representatives or legal authorities. Being in a position of epistemic authority is the manifestation of institutional practices grounded in the ideal of objectivity and the univocal and unambiguous existence of one truth. The knowledge held by these experts—as opposed to residents witnessing development—has been gained on the books and on the job, thereby bestowing them with epistemic authority. Hence, lawyers, engineers, and industry representatives are largely considered to be stakeholders that can unequivocally make informed decisions regarding gas and oil development.

At almost the exact opposite end of the spectrum lies situated knowledge, which stresses the contingent, hierarchical, experiential, and relational nature of knowledge production (Rose, 1997). Living in a certain location and experiencing a certain sociocultural context or phenomenon on a daily basis (for example, pipeline development) allows one to notice changes in their surroundings and to gain a deep understanding of that situation that simply cannot be secured through titles alone. Such situated knowledge is deeply circumstantial and contextual. It is ingrained in the person that lives in a location and through a phenomenon (Rose, 1997; Haraway, 1990). Additionally, situated knowledge evolves over time and is shaped by social relationships” (Caretta, 2015). While situated knowledge is often not recognized by a positivist institutional understanding of knowledge and expertise that Western society is grounded upon, we argue that situated knowledge is just as important as other forms of knowledge when it comes to communications around environmental risk. One way in which such situated knowledges are often shared is through storytelling.

Stories are situated—rooted in specific contexts and places—and illuminate the cultural, material, and historical connections between place and technological progress (Edwards, 2020). Stories are also flexible, “ideal for engaging considerations of social justice by privileging participant agency and voice” (Jones, 2016, p. 480), and powerful, as “stories broker change because they mediate between social structures and individual agency” (Faber, 2002, p. 25). Stories connect community members to knowledge and to one another, making them integral to addressing public problems. Since “stories are the data used making sense of the past and predicting the future” and are the foundation of our individual and group identities (Small, 2017, p. 240), they deserve attention in conversations about development that impacts communities. By listening to and amplifying the experiences of community members, TPC professionals can position situated storytellers as experts in their own right, leaning into the belief that “citizens can participate in technical discussions of policy and have valuable information to contribute to the decision-making process” (Simmons, 2007, p. 130).

METHODS

Driven by the commitment to highlight the experiences of rural West Virginia residents who have witnessed the outcomes of pipeline development, we used place-based participatory methods in this study: photovoice and walk-along interviews. Photovoice is a research method that asks participants to take pictures of their daily lives in order to reflect on their concerns (Sullivan, 2017), often shared through narratives relayed in subsequent interviews or focus groups (Carlson, 2021). Similarly, walk-along interviews allow participants to lead the researcher through their lived experience of a place and invites them to share data through stories (Carpiano, 2009). As a technical communicator and a geographer, we come from different disciplinary backgrounds, but two primary methodological similarities emerged in this project: first, place is an integral component of lived experience that is not always accounted for in empirical studies; and second, visual research methods often elicit rich stories that hold great significance for community members. The inclusion of participants, their places, and their stories in discourse about environmental risk and how to mitigate it is of great concern for technical communicators working around these issues.

Since photovoice allows participants to capture their perceptions over a period of time and then reflect on their images with researchers, the participants in this study were able to share insights on how their land was changing over time. Leading up to interviews, participants took photos of their property and collected pictures they had taken in the past. Then, during our walk-along interviews, they shared these pictures and showed us around their property so that we could see first-hand the impact that pipeline development had on their land. Together, these methods illuminated participants’ place-based knowledge and deepened researchers’ understanding of residents’ everyday lived experiences in the wake of pipeline buildout.

In Summer 2020, we conducted 31 socially-distanced, masked interviews across central and eastern West Virginia. We initially recruited participants through several local and regional email listervs and social media groups related to natural gas pipeline development; however, our participant pool increased through snowball sampling, where participants shared members of their social networks (often neighbors) who were also affected by pipeline development. As a result, we were able to speak with landowners who had varying opinions on pipeline development. After completing the interviews, they were transcribed and shared with participants for member-checking (Caretta, 2016). Transcripts were analyzed for references to expertise, knowledge, information, and education, with particular attention directed towards how these concepts were situated within participant stories, through codes developed in Nvivo, a qualitative analysis software.

We then set out to validate these initial findings through a survey and a virtual focus group as part of the member-checking process. The survey asked questions about concerns and property value and used images we gathered from interviewees to gauge whether similar events were witnessed by survey participants. We distributed the survey to residents in West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, in order to include landowners we were not able to interview during the summer due to COVID-19 limitations, and to check results against the experiences from other areas in West Virginia and the region as a whole. Finally, preliminary results and analysis from both the 31 interviews and 48 survey responses were used as the basis for member checking through a focus group. The focus group was held via Zoom in November 2020 with eight participants, each of whom had direct experience with pipeline development on their land.

EPISTEMIC PERSPECTIVES ON PIPELINE DEVELOPMENT ROOTED IN TECHNICAL AND LEGAL KNOWLEDGE

Energy development is a complex process, with several forms of technical and legal knowledge accorded varying levels of epistemic authority. Major decisions about pipeline construction are typically made by industry stakeholders with some input from federal, state, and local policymakers. Industry representatives often work with federal- and state-level agencies to gain legal approval for their plans and to set up regulatory relationships with agencies like the Department of Environmental Protection. They also develop relationships with local governments and economic development groups.

Throughout this process, epistemic authority typically manifests through technical and legal understandings of land, rather than lived experiences of landowners or community members. For instance, being an engineer endows one with an assumed expertise over the lay of the land that cannot be called into question by community members who have resided in the area for decades. Engineers are given authority over the knowledge and, ultimately, the planning and implementation of pipelines because they possess a degree attesting their knowledge in such a field—even if they have never physically visited the very property they make plans to develop (which is often the case, according to interviewees, who told us that many engineers are located states away). In fact, conversations with landowners often occur well after plans are drawn up; many participants reported learning about pipeline plans for the first time well after construction had started in their counties, confirming that landowners’ situated knowledges did not factor into development decisions.

Technical Measurements of Land and Scientific Calculations of Risk

Technical documents and scientific measurements are central to pipeline development. Various subject matter experts contribute their knowledge to technical documents, including: surveyors who create topographical maps of possible development sites; engineers who plan pipeline paths; environmental testing firms that set up air or water monitoring systems; and gas company representatives (known commonly as “landmen”) who interpret these documents in conversations with landowners. Documents like maps and testing reports are shared as supposedly objective accounts and, therefore, factor heavily into decisions made by industry representatives and landowners alike.

Perhaps the most frequent technical account of land that participants referenced were maps. They mentioned maps of all stripes—from their own records, from the company, and from the county assessor’s office. According to multiple participants, these maps were important for landowners, who used maps to advocate for themselves during negotiations, and for gas companies, who used maps to justify and execute pipeline construction. Several mentioned the importance of tax maps as public records and suggested that companies try to plan construction through “farming fields . . . wide open spaces cost them less money” than steep inclines that dominate West Virginia landscapes (Participant 6).

Maps were also an important source of information for participants as they sought to learn more about pipeline development in their communities. Participant 10 mentioned the use of maps at public meetings presented by energy companies. Participant 1 told us that they frequently looked at online maps showing pipelines across the United States, since companies were required to share interstate and in-state lines alike. Participant 8 said that they inadvertently found out that plans for their property were already finalized, without their input, because they had looked closely at a map a landman provided during a visit. These documents are the manifestation of that epistemic authority that residents have not been able to attain, as they do not possess the skills to produce these maps and hence, could not challenge the authority of those documents; however, as Eichberger (2019) notes, maps are by nature a product of selection and exclusion, but “omissions, even if unintended . . . silence certain voices telling certain parts of the story” (p. 18). Maps are fundamentally incomplete, requiring us to consider what elements are left out in their creation. Further, depending on who creates the map and what elements it shows, constructions of risk vary widely.

On the contrary, soil and water baseline tests, paid out of pocket by landowners, are something that residents often are able to use to counter the industry’s own baseline testing. Typically, a company takes soil and water baseline samples from residential areas before pipeline construction begins, but rarely shares results voluntarily with local residents. Additionally, because the industry directs such tests, those samples are tested through labs that local residents often describe as favorable to the industry. So, even if residents do have the financial resources to pay for their own tests, they often find that their own tests contradict the industry-sponsored test results. Having the financial resources to be able to hire a lab to conduct independent testing periodically is crucial to have any recourse against the industry in the event that soil or water gets contaminated. Participant 11 had their water tested six times in 13 years because they wanted to have records of their water quality over time but expressed frustration with how expensive it was. Participant 12, when asked if there was one piece of advice they could give to someone in a similar situation, said, “Test your water, test your air. Document where you are, get your baseline.”

Outsourcing epistemic authority to independent experts that can challenge industry experts provides residents with some assurance that if their water or soil were to be contaminated, they would have proof to demand compensation and remediation from the industry. Test results might also indicate if they might need to stop drinking their water or eating food from their own garden (see Turley & Caretta, 2020). For the participants who could afford them, these tests were a significant source of security. Participant 1 said that after many encounters with the company, they were able to get results from a water test conducted by a supervisor and thought “the only reason that happened was because I was such a pain in the butt.” After they had accessed public records to see what testing procedures the company had proposed for their entire county, they were shocked to find out that “as close as they were to some homes, they only had four water well tests scheduled.” Companies and regulatory entities alike locate power in official definitions and documents, leaving little room for landowners’ experiences in larger conversations about energy development—especially if those experiences contradict industry accounts. Ultimately, while official documents suggest low levels of risk, the experiences of landowners and residents might suggest a heightened sense of risk; TPC practitioners should be aware of these different accounts and take landowner experience into consideration.

Legal Definitions of Land and Landowner Rights

Another source of epistemic authority that dominates pipeline development is the law. Andrews and McCarthy (2014) point out that when it comes to extractive industries, the formal legal realm is “sufficiently complex and ambiguous” with resources that can be leveraged in multiple ways (p. 13). All 31 participants referenced the importance of federal, state, and/or local laws in governing pipeline development. Many also talked about mineral rights and surface rights. In energy-rich areas such as West Virginia, land ownership and mineral ownership are often separate: that is, there is one deed for the surface area of a property and a separate deed for the natural resources that lie below the ground—minerals, coal, and often natural gas or oil. Making circumstances more complicated, sometimes mineral rights are leased, meaning that someone other than the deed-holder is receiving compensation for extracted minerals. As a result, mineral rights are a confusing, yet determining factor in pipeline development. (Though our discussion of land ownership is focused on contemporary law, these properties are on the ancestral lands of the Cherokee, Shawnee, Saponi, and Delaware people, whose experiences are not captured in our work because they were forced from this land. We would like to note this because even as we seek to honor the place-based knowledge of residents, this knowledge is tangled in complex histories.)

Full mineral ownership was relatively rare among the participants we spoke with. In some scenarios, the minerals and the surface were split as early as the 1800s, meaning that mineral owners might be several generations removed from the property and therefore unconcerned with what happens to the landscape. When asked if they still owned their mineral rights, Participant 9 responded, “No. Nobody does . . . Mine were taken in 1889.” This sentiment was echoed by many others. For those that did possess mineral rights, they usually did not have the rights to their entire parcel of land; oftentimes, mineral rights are split between many parties. Participant 31 estimated that there were dozens of other mineral owners linked to their individual parcel of land.

If a landowner does not have the rights to their minerals, they have no say in how (or when, or if) resources are extracted from underneath their property; however, they can dispute changes to the actual landscape, such as the construction of well pads or other structures. But often, that isn’t enough to prevent the extraction of gas from their parcel of land. According to Participant 3, “The company could’ve said, ‘Okay, here’s the lease from 1896 for the minerals that were leased off this property. We’re going to go by this lease, by the letter of the law, and we can come in here and do whatever we want,’ which they can.” Law, then, becomes an important source of knowledge for stakeholders because it directly affects what rights landowners have and what actions they might take. Land use laws are complicated, and most participants consulted lawyers at some point in their dealings with energy companies: “There’s no way that anybody can fight, negotiate, know all the ins and outs that you need to know without at least talking to a lawyer” (Participant 26).

Landowner agency is significantly restricted by technical and legal understandings of land, which often oversimplify land issues and can be used to stifle the concerns of landowners. These definitions contribute to power dynamics that place well-resourced industry stakeholders in a position of epistemic authority and control. And while these forms of knowledge do not necessarily negate the expertise of landowners, they are often wielded by institutional powers in ways that render landowner experience as less reliable, and therefore, less valuable. This dynamic leads to significant gaps between stakeholders during pipeline development. Lived experiences are practically never represented in official narratives about pipelines; as a result, these accounts are incomplete, since landowner and resident knowledges arguably capture the most intimate and up-close accounts of pipeline development in rural communities. TPC professionals should seek out situated, place-based accounts alongside more traditionally accepted accounts from technical and legal experts.

SITUATED PERSPECTIVES OF RURAL LANDOWNERS AND RESIDENTS

Given the dominance of technical and legal expertise, resident accounts of events are often under-valued; however, the residents we spoke with shared many insights that only they could have because of their familiarity with their places. These insights are not documented in an official report or represented on a map, but they are just as important for cataloging the effects and risks of pipeline development. What’s more, these insights were shared through rich stories—stories that demonstrate how closely tied together land and life can be. Landowner expertise, then, offers a dynamic and accurate account of how natural gas pipelines have shaped the lives of rural community members, often packaged in narrative. As a result, resident stories should be valued as an important form of insight in development scenarios.

Landowners Possess Specialized Topographical Knowledge

First, landowners possess knowledge about their land: in fact, they know that land better than anyone else. Many of the landowners we interviewed were deeply acquainted with the landscapes around them, as they built homes, farmed crops, gathered mushrooms, and raised livestock. In every single walk-along interview, participants talked in great detail about their land, showing us exactly what they were talking about, either through photographs or as they walked us around their property. This keen spatial awareness can only be developed through firsthand engagement with the land. And as participants pointed to different markers or areas that had been damaged or changed by development, they told us stories—stories about their family, about their childhood, and about their livelihoods. Their stories are both a mode of transmitting knowledge and a method for illuminating the complexities of environmental change, all the while building relationships between storyteller and listener.

Many participants shared, in significant detail, their recollections of conversations with gas company representatives sent to negotiate a settlement for land to be used for pipeline construction. Several participants challenged initial settlement offers based on incomplete assessments of their land’s assets. For example, Participant 8 showed their landman pictures of a few well-placed acres that could be the site of vacation rentals or recreational space, increasing its value. As a result, the pipeline representatives added 30%–40% in the next offer “because they could now understand a scenic view of the land” which hadn’t been initially captured in tax records or maps. This evidence, which would not be categorized as grounded in epistemic authority, embodies the contextual, observational, and experiential nature of situated knowledge.

In several interviews, participants noted that energy company maps didn’t always match their own knowledge of what the property actually looked like. For example, focus group (FG) Participant 1 shared that their family’s property had several ephemeral streams, or dry stream beds that only fill after significant rainfall. Couched in a longer story explaining how growing up in West Virginia had shaped their knowledge of how water interacts with steep hillsides, they said, “I mean, it might look dry in August when the surveyors are out there, but we know where the streams are.” A map is a static representation of a landscape at one particular moment: even though there is absolutely a stream in a location multiple times during the year, “it’s not there, according to the map, or according to the geologist.” FG Participant 3 echoed FG Participant 1 by sharing that they had experienced a similar situation in regards to natural water sources. They noted that the maps from a major pipeline project “failed to list springs that were very obvious springs.” Though all participants gestured towards maps as an authority in some scenarios, these reflections demonstrate that maps do not always accurately represent a natural environment. Maps, in fact, are often produced by experts that do not reside on site and hence, easily miss seasonal shifts such as ephemeral springs or mud slides.

Several participants suggested that difficulties with pipeline construction, such as slips (areas where a pipeline had started leaking because of the steep terrain) were related to the mountainous landscape of the region. Such terrain had not been effectively represented in the aforementioned maps, leading to faulty excavation and construction patterns, which then can mean issues with erosion or leaks later. Accordingly, participants repeatedly pointed to the importance of first-hand knowledge of a landscape, and how static representations might not accurately communicate “the problems going up and down these steep slopes” (Participant 18) to construction crews.

Landowners Witness Firsthand the Effects of Pipeline Construction

During construction periods, which usually lasted several months during the spring or summer, participants reported significant disruptions to their daily lives. Many mentioned a worsening of air quality during pipeline construction, in addition to light pollution at night if crews were coming up against a deadline. Heavy equipment traffic on unpaved roads, running engines, digging, and blasting contributed to the increase of dust and fumes which lowered quality of life for rural populations used to silent, quaint roads and clean air (Caretta et al., 2021). Since participants can’t escape these construction zones, they are forced to contend with the stresses of pipeline development constantly, and had many stories teeming with disruption, exhaustion, and frustration.

Landowners also understand how changes to the natural environment might heighten environmental risks. Participant 10 shared that, as someone whose primary water source is a shallow well, they were constantly worried about water quality and availability: “And then you would see these trucks sucking water out of the creek. And you know we have some years of drought and you see just muddy creek bottoms, and it was very upsetting.” Here, Participant 10 demonstrates their knowledge of the shifts in water volume during particular periods of time, as well as an understanding that siphoning gallons of water out of creeks could have an-area wide effect on supply. FG Participant 1 said that, “I would know not just my own property, but [generally] how water works around here . . . how soil works, how the soil is moving.” They located their knowledge in their time “growing up here”: “It’s not just dealing with this with pipelines, but also highway construction around here. Everybody who sees where they’re gonna put these things is like, that ain’t gonna work. And no one listens.” FG Participant 1’s knowledge is situated in their decades of living and working in West Virginia and witnessing how construction projects might result in unsafe infrastructure that needs unexpected maintenance.

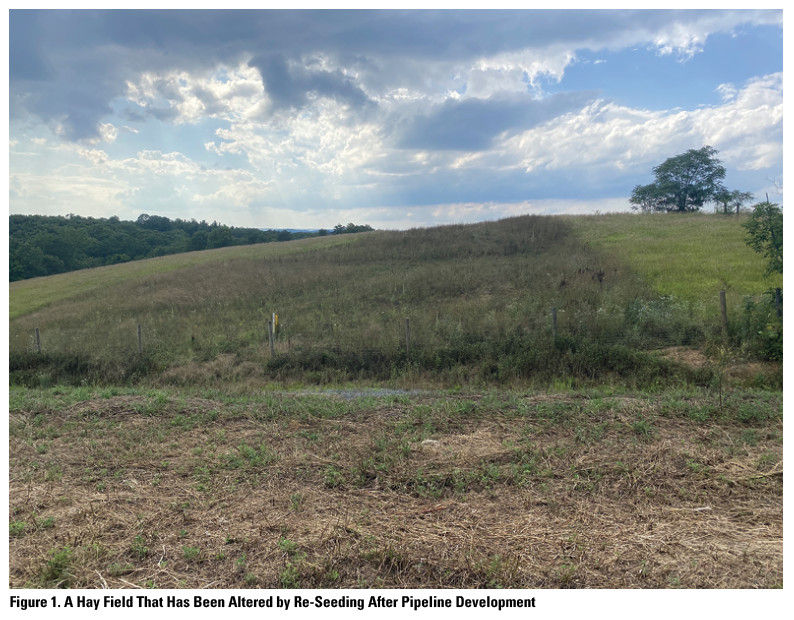

Many participants shared such feelings of not being listened to, as they felt their property had been forever altered by the construction of pipelines. Participant 6 lived on a farm that had been in their family for nearly a century, and in 2016, pipeline construction began. After an extended legal battle, their family was forced to settle with the company, which sited a pipeline directly through their farm and “ruined probably 6 or 8 acres of our best grass.” After digging a trench and burying the pipeline, workers were supposed to re-seed the area:

But it’s nothing but a weed patch . . . They had it separated, the good topsoil and the other stuff, and they put it all in but then they worked it so much that when they put the topsoil in they bunched it right down into the shale. So there was nothing there. They didn’t know what they were doing at all. (Participant 6)

Figure 1 demonstrates what Participant 6 described to us in their longer story that outlined how pipeline development had occurred on their land over a number of years. In the middle of the photo, there is a large strip of field that appears darker than the rest of the field, marking where the pipeline has been buried several feet below the surface. That strip is markedly different in consistency and color, assumedly from the grasses that are now growing there and the change in soil quality. While at first glance, this might not be significant, the story that this image is rooted in—one of sadness and lingering frustration—reveals its significance, as that land can no longer yield hay, which is an important crop for the family business. For Participant 6, this strip of land is the manifestation of years of struggle that had irreversible effects on their family, their business, and their land.

Health and safety concerns were another shared theme among participants. FG Participant 2 expressed frustration with how they and their neighbors contacted regulatory organizations with concerns about unusual odors near the 36-inch pipeline in close proximity to their homes. Despite their repeated efforts, FG Participant 2 stated that no action had been taken, citing the “false idea” that “if [pipeline developers] get a permit, that means it’s safe.” They continued that powerful decision-makers, protecting their own interests:

They try to brush off the actual facts. They try to treat the people as if they don’t know what they’re talking about. ‘So, it smells bad? That’s not really dangerous’ . . . it’s like they put their hands on their ears and close their eyes and just flip a coin for our safety. (FG Participant 2)

Even though FG Participant 2 and their neighbors followed all of the proper steps to report their issues, their experiences were not validated by institutions with epistemic authority. This caused participants frustration and fear, as they felt they were living in risky situations and their knowledge was continually dismissed, rather than being seen as specialized, situated, and important. Repeatedly, participants demonstrated their depth of knowledge—about their land, about natural gas pipeline development at large, and about the deep, lasting impact of this development on their lives and livelihoods. This knowledge often emerged as they shared their memories of growing up on that land as a child or moving onto a property after getting married. For example, we, as the researchers, would walk along with participants across their property, and they would oftentimes point to a tree or a creek, and then tell a rich, often lengthy story about how that marker had been changed or preserved throughout development. And despite this knowledge, they repeatedly told stories of how that knowledge had been dismissed by powerful stakeholders.

Markers of place can be entry points for conversations about the impact of technological and environmental development. TPC professionals working with affected communities might seek out opportunities for residents to share important markers of place and subsequently reveal important insights about risk.

CONCLUSION: FRAMING STORIES BASED ON SITUATED KNOWLEDGE AS EXPERTISE

While landowners are typically not seen by industry or policymakers as having special knowledge of pipeline development—and are often actively dismissed or ignored by those actors—they are experts in their own right. Their in-depth knowledge of their property and how it appears in different seasons and under different conditions gives them insight into how pipeline development might impact natural features that one-dimensional, straightforward representations of land and risk simply don’t have. Additionally, landowners live in direct proximity to pipelines and related infrastructure and see on a daily basis what changes might occur as a result of that development. The situated knowledge of community members living alongside natural gas pipelines and accompanying infrastructure is just as important to ongoing conversations about energy development as the epistemic authority rooted in technical, scientific, and legal accounts of land and natural resources. And stories are fundamental in efforts to assemble a robust account of how energy development heightens environmental risks, including in rural areas where vulnerable community members shoulder the burdens of such development.

In addition to topographical and experiential knowledge, landowners and residents possess knowledge about their communities and how energy development has shaped the region as a whole. Repeatedly, participants referenced the deep presence of extractive interests in West Virginia: first, it was coal or timber logging; then hydraulic fracturing; and now, natural gas pipelines. “It is an economic justice issue. And we’ve been an extraction state for 150 years,” Participant 7B said. “And we still rank at the bottom, in lots of social and economic measures of wellbeing and health.” This history, along with the dominance of the energy industry in the state (not to mention the development-friendly policies passed in the state legislature) has created a system “rigged against landowners” (FG Participant 2). By locating their own experiences in larger cultural narratives, especially those related to the dynamics between extractive industries and communities in Appalachia, participants shared their connections to a long, often painful history.

This history is made up of stories—shared cultural tales and individual experiences that demonstrate the importance of bearing witness to social, cultural, and environmental changes over time. The role of stories in knowledge formation cannot be understated. And while stories are, by their nature, incomplete and subjective, they still hold important insight that should be taken into account as we try to map out the implications of any sort of development that heightens environmental risk. As Hemmings (2005) argues, in telling stories that counter dominant narratives, we must “be attentive to the affective as well as technical ways” that stories work (p. 120). Stories anchor specialized knowledge that often is not heeded. Simply put, landowners are experts of place, because of their situated knowledges that illuminate the connections between different elements of place, and stories are one way of encapsulating and sharing that expertise.

Technical communicators ought to not only seek out the stories of community members living with heightened levels of environmental risk, but to actively amplify those stories and advocate for those stories to be included in official accounts of energy development—accounts that often only include legal or technical information. Technical communicators working in energy or related sectors might note the type and source of data they work with: Are all stakeholder perspectives reflected in this data? Are there elements missing from these renderings of development? Have there been efforts to connect with vulnerable members of rural communities (e.g., elderly, disabled, poor) who do not have the resources to seek out legal or technical experts to speak on their behalf? And, how is place represented in this information? Place has found its way into designing for locative media (Fagerjord, 2017) and public planning (Moore, 2017a), but a more expansive understanding of how place shapes all technological and environmental development would offer technical communicators multiple entry points into conversations with stakeholders as well as opportunities to emphasize the lived expertise of residents alongside other, more traditional accounts.

Participatory and place-based methods, like those we used to conduct this research, are one way that TPC practitioners can invite stories and amplify the experiences of communities directly affected by technological and environmental changes, including energy development. Adopting place-based methods like walk-along interviews—not so different from think-aloud protocols commonly used in user testing (van den Haak et al., 2007)—and photovoice—not so different from using visual narrative or graphics in a user-testing scenario (Loel, 2005)—is one way that TPC professionals can make space for situated knowledges. As technical communicators find themselves in increasingly diverse professional spaces and working to address different types of problems, it becomes even more important to develop methods for engaging the knowledges of all stakeholders. Strategies for eliciting stories practically and methodologically privilege the lived experiences of community members. To develop and utilize such strategies is an ethical choice in an arena where “knowledge and risk [are] mediated through corporate interest” (Hopton, 2019, p. 6). Technical communicators can not only adapt the methods shared in this article, but might also make room for stories and storytelling in their work in other ways as well.

In this study, participants shared their stories about natural gas pipeline development, illuminating risks inherent in the process that are often not made visible. And while TPC has recently begun to embrace stories as a way to seek out and share knowledge, that is not universally the case, resulting in the continued de-valuation of situated knowledges that are often rooted in place. While we agree with Mazurkewich (2018) that “technical experts need to get better at telling stories,” we argue that technical experts need to get better at listening to stories, too, and acknowledging that situated knowledges are expertise that should be consulted in scenarios where communities are subject to heightened environmental risk.

REFERENCES

Aguilar, G. L. (2020). Migrants as place-makers: The role of technical communicators in (re)locating place. Proceedings of the 38th ACM International Conference on Design of Communication, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1145/3380851.3416758

Andrews, E., & McCarthy, J. (2014). Scale, shale, and the state: Political ecologies and legal geographies of shale gas development in Pennsylvania. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 4(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-013-0146-8

Ballentine, B. (2019). Rhetoric, risk, and hydraulic fracturing: One landowner’s perspective. Communication Design Quarterly, 7(1), 54–63.

Bell, S. E., & York, R. (2010). Community economic identity: The coal industry and ideology construction in West Virginia. Rural Sociology, 75(1), 111–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2009.00004.x

Brantley, S. L., Yoxtheimer, D., Arjmand, S., Grieve, P., Vidic, R., Pollak, J., Llewellyn, G.T., Abad, J., & Simon, C. (2014). Water resource impacts during unconventional shale gas development: The Pennsylvania experience. International Journal of Coal Geology, 126, 140–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2013.12.017

Buchanan, B. P., Auerbach, D. A., McManamay, R. A., Taylor, J. M., Flecker, A. S., Archibald, J. A., Fuka, M., & Walter, M. T. (2017). Environmental flows in the context of unconventional natural gas development in the Marcellus Shale. Ecological Applications, 27(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1425

Bugden, D., & Stedman, R. (2019). Rural landowners, energy leasing, and patterns of risk and inequality in the shale gas industry. Rural Sociology, 84(3), 459–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12236

Caretta, M. A. (2015). Situated knowledge in cross-cultural, cross-language research: A collaborative reflexive analysis of researcher, assistant, and participant subjectivities. Qualitative Research, 15(4), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794114543404

Caretta, M. A. (2016). Member checking: A feminist participatory analysis of the use of preliminary results pamphlets in cross-cultural, cross-language research. Qualitative Research, 16(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115606495

Caretta, M. A., Carlson, E. B., Hood, R., & Turley, B. (2021). From a rural idyll to an industrial site: An analysis of hydraulic fracturing energy sprawl in Central Appalachia. Journal of Land Use Science. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2021.1968973

Carlson, E. B. (2021). Visual participatory action research methods: Presenting nuanced, co-created accounts of public problems. In R. Walton & G. Y. Agboka (Eds.), Equipping technical communicators for social justice work: Theories, methodologies, and pedagogies (pp. 98-115). Utah State UP.

Carpiano, R. M. (2009). Come take a walk with me: The Go-Along interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health & Place 15(1), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003.

Edwards, D. W. (2020). Digital rhetoric on a damaged planet: Storying digital damage as inventive response to the Anthropocene. Rhetoric Review, 39(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350198.2019.1690372

Eldridge, E. (2018). Administrating violence through coal ash policies and practices. Conflict and Society, 4(1), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.3167/arcs.2018.040109

Eichberger, R. (2019). Maps, silence, and Standing Rock: Seeking a visuality for the age of environmental crisis. Communication Design Quarterly, 7(1), 9–21.

Emanuel, R. E., Caretta, M. A., Rivers, L., & P. Vasudevan. Natural gas gathering and transmission pipelines and social vulnerability in the United States. Manuscript submitted for publication. GeoHealth. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GH000442

Faber, B. (2002). Community action and organizational change: Image, narrative, identity. Southern Illinois University Press.

Fagerjord, A. (2017). Toward a rhetoric of the place: Creating locative experiences. In L. Potts & M. J. Salvo (Eds.), Rhetoric and experience architecture (pp. 225-240). Parlor Press.

Finewood, M. H., & Stroup, L. J. (2012). Fracking and the neoliberalization of the hydro-social cycle in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale. Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education, 147(1), 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1936-704X.2012.03104.x

Fleischman, L., & Franklin, M. (2017). Fumes across the fence-line: The health impacts of air pollution from oil and gas facilities on African American communities. Retrieved from https://naacp.org/resources/fumes-across-fence-line-health-impacts-air-pollution-oil-gas-facilities-african-american

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press.

Frost, E. (2018). Apparent feminism and risk communication: Hazard, outrage, environment, and embodiment. In A.M. Haas & M.F. Eble (Eds.), Key theoretical frameworks: Teaching technical communication in the twenty-first century (pp. 23-45). Utah State University Press.

George, B. (2019). Communicating activist roles and tools in complex energy deliberation. Communication Design Quarterly, 7(1), 40–53.

Gruenspecht, H. (2019). The U.S. coal sector: Recent and continuing changes. Cross-Brookings Initiative on Energy and Climate. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-u-s-coal-sector/

Haas, A. M., & Eble, M. F. (2018). Introduction: The social justice turn. In A.M. Haas & M.F. Eble (Eds.), Key theoretical frameworks: Teaching technical communication in the twenty-first century (pp. 3-22). Utah State UP.

Haraway, D. (1990). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women (pp. 183-201). Routledge.

Hemmings, C. (2005). Telling feminist stories. Feminist Theory, 6(2), 115–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700105053690

Herndl, C. G., Hopton, S., Cutlip, L., Polush, E. Y., Cruse, R., & Shelley, M. (2018). What’s a farm? The languages of space and place. In C. Rai & C. G. Druschke (Eds.), Field rhetoric: Ethnography, ecology, and engagement in the places of persuasion (pp. 61-94). University of Alabama Press.

Hopton, S. (2019). The revenge of Plato’s pigs. Communication Design Quarterly, 7(1), 4–8.

Johnston, J. E., Chau, K., Franklin, M., & Cushing, L. (2020). Environmental justice dimensions of oil and gas flaring in south Texas: Disproportionate exposure among Hispanic communities. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(10), 6289–6298.

Jones, N. N. (2016). Narrative inquiry in human-centered design: Examining silence and voice to promote social justice in design scenarios. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(4), 471–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616653489

Kurlinkus, W., & Kurlinkus, K. (2018). Coal keeps the lights on: Rhetorics of nostalgia for and in Appalachia. College English, 81(2), 87–109.

Legg, E., & Strantz, A. (2021). I’m surprised this hasn’t happened before: An indigenous examination of UXD failure during the Hawai’i missile false alarm. In R. Walton & G. Y. Agboka (Eds.), Equipping technical communicators for social justice work: Theories, methodologies, and pedagogies (pp. 49-74). Utah State UP.

Lindeman, N. (2013). Subjectivized knowledge and grassroots advocacy: An analysis of an environmental controversy in northern California. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 27(1), 62–90.

Loel, K. (2005). Tracing visual narratives: User-testing methodology for developing a multimedia museum show. Technical Communication, 52(2), 121–137.

Mazurkewich, K. (2018, April 13). Technical experts need to get better at telling stories. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/04/technical-experts-need-to-get-better-at-telling-stories

Moore, K. (2017a). Experience architecture in public planning: A material, activist practice. In L. Potts & M. J. Salvo (Eds.), Rhetoric and experience architecture (pp. 143-165). Parlor Press.

Moore, K. (2017b). The technical communicator as participant, facilitator, and designer in public engagement projects. Technical Communication 64(3), 237–253.

Office of Pipeline Safety (2021, February 10), PHMSA Pipeline Safety Program. U.S. Department of Transportation. https://primis.phmsa.dot.gov/comm/GeneralPublic.htm?nocache=1635

Pflugfelder, E. H. (2019). Risk selfies and nonrational environmental communication. Communication Design Quarterly, 7(1), 73–84.

Powell, M., Levy, D., Riley-Mukavetz, A., Brooks-Gillies, M., Novotny, M., & Fisch-Ferguson, J. (2014). Our story begins here: Constellating cultural rhetorics. Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture 18. http://enculturation.net/our-story-begins-here

Rose, E. J. (2016). Design as advocacy: Using a human-centered approach to investigate the needs of vulnerable populations. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(4), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616653494

Rose, G. (1997). Situating knowledges: Positionality, reflexivities and other tactics. Progress in Human Geography 21(3), 305–20. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913297673302122.

Ross, D., Oppegaard, B., & Willerton, R. (2019). Principles of place: Developing a place-based ethic for discussing, debating, and anticipating technical communication concerns. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 62(1), 4–26. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8528511

Sackey, D. J. (2019). An environmental justice paradigm for technical communication. In A.M. Haas & M.F. Eble (Eds.), Key theoretical frameworks: Teaching technical communication in the twenty-first century (pp. 138-162). Utah State University Press.

Simmons, W. M. (2007). Participation and power civic discourse in environmental policy decisions. State University of New York Press.

Simmons, W. M., & Grabill, J. T. (2007). Toward a civic rhetoric for technologically and scientifically complex places: Invention, performance, and participation. College Composition and Communication, 58(3), 419–448.

Small, N. (2017). (Re)kindle: On the value of storytelling to technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 47(2), 234–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281617692069

Sullivan, P. (2017). Participating with pictures: Promises and challenges of using images as a technique in technical communication research. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 47(1), 86–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616641930

Tillery, D. (2003). Radioactive waste and technical doubts: genre and environmental opposition to nuclear waste sites. Technical Communication Quarterly, 12(4), 405–421.

Turley, B., & Caretta, M. A. (2020). Household water security: An analysis of water affect in the context of hydraulic fracturing in West Virginia, Appalachia. Water, 12(1), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12010147

U.S. Energy Information Administration [EIA] (2021, February 10). West Virginia Natural Gas Production. https://www.eia.gov/dnav/ng/hist/na1160_swv_2a.htm

van den Haak, M. J., de Jong, Menno D. T., & Schellens, P. J. (2007). Evaluation of an informational web-site: Three variants of the think-aloud method compared. Technical Communication, 54(1), 58–71.

Walton, R., Moore, K., & Jones, N. N. (2019). Technical communication after the social justice turn: Building coalitions for action. New York: Routledge.

Willow, A. J., & Wylie, S. (2014). Politics, ecology, and the new anthropology of energy: Exploring the emerging frontiers of hydraulic fracking. Journal of Political Ecology, 21(1), 222–236. https://doi.org/10.2458/v21i1.21134

Wing, S., & Johnston, S. (2014). Industrial hog operations in North Carolina disproportionately impact African-Americans, Hispanics, and American Indians. North Carolina Policy Watch. Retrieved from https://www.ncpolicywatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/UNC-Report.pdf

Youngblood, S. A. (2012). Balancing the rhetorical tension between right to know and security in risk communication: Ambiguity and avoidance. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 26(1), 35–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651911421123

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the landowners who shared their stories and expertise with us. We also would like to thank the West Virginia University Humanities Center and the Heinz Foundation for funding our research.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Erin Brock Carlson is an assistant professor in the Department of English at West Virginia University, where she teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in the Professional Writing and Editing Program. Her current research addresses community organizing, place-based development, and collaborative knowledge making through participatory visual methodologies. Erin’s work has appeared in Technical Communication Quarterly, Journal of Business and Technical Communication, and Computers and Composition, among others. Dr. Erin Brock Carlson can be contacted at erin.carlson@mail.wvu.edu.

Dr. Martina Angela Caretta is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Human Geography at Lund University, Sweden. She holds a PhD in Geography from Stockholm University. She is a feminist geographer with expertise in water, climate change adaptation, gender and participatory methodologies. She has carried out extensive fieldwork in East Africa, Latin America and Appalachia. Her work has been published in Gender, Place and Culture; Annals of the AAG, Frontiers Water, Qualitative Research among others. Dr. Martina Angela Caretta can be contacted at martina_angela.caretta@keg.lu.se.