doi: https://doi.org/10.55177/tc227091

By Guiseppe Getto and Suzan Flanagan

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Contemporary non-profit organizations must reach a variety of audiences in order to sustain themselves and must compel these audiences to take action on behalf of a specific cause. At the same time, past research has indicated that non-profit professionals often lack the necessary training and expertise to leverage digital technologies for effective communication. This research study explores how technical communicators can assist non-profits by helping them develop effective content strategies.

Method: This report of research findings is based on an ongoing Participatory Action Research (PAR) project, which included a series of focus groups with representatives of thirteen different organizations as well as interventions with several other organizations. The goal has been to learn about and help improve non-profit content strategy in the community of Greenville, North Carolina.

Results: We found that while non-profits do rely on a variety of media to fulfill their goals, they prefer pre-digital media. Our participants also defined audiences in a very loose manner, used content in a non-targeted way, and favored existing organizational processes over content strategy best practices.

Conclusions: Ultimately, we provide several ways technical communicators can assist non-profits through low-cost or free consulting and the development of educational materials. We hope that fellow professionals will engage in this necessary work because non-profits in the United States form an important “third sector” of the economy that provides essential services to countless individuals.

KEYWORDS: content strategy, non-profit, technical communication, participatory action research (PAR), social justice

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Contemporary non-profit organizations need help with content strategy in order to reach their intended audiences.

- We conducted a focus group with several non-profits and determined that they are largely unaware of content strategy best practices including audience targeting, content planning, and melding organizational goals with content goals.

- Technical communicators can help local organizations improve their content strategy processes.

- Technical communicators can help improve content strategy processes through service work or low-cost consulting.

INTRODUCTION

To sustain their organizations, non-profits must reach a variety of community audiences, including potential volunteers, donors, funders, and clients, as well as existing supporters and clients of their organization. As organizations they must often compete for media attention and funding with other non-profits as well as with small businesses and corporations. Successful non-profits must also build and sustain a compelling web presence in order to interact with community audiences, many of whom use contemporary communication channels such as search engines, social media, and blogs to get updates on their favorite causes and charities. As many in the field of technical communication know, these newer media require the development of a content strategy if they are to be deployed effectively. At the same time, the most recent extant large-scale research on non-profit communication has shown that non-profits struggle to use these newer media to reach their goals (Kenix, 2008; Zorn, Flanagin, & Shoham, 2010). Years later, however, it is unclear whether non-profits have improved their use of digital media or have adopted alternative content strategies.

And though most technical communication practitioners work in a corporate setting, many also volunteer with non-profits in their local communities.[1] To date, there has been no systematic research into the various ways technical communication practitioners volunteer with non-profits, but anecdotally, practitioners have reported to us that they volunteer in a variety of ways, including by providing free writing or editing services; helping organizations optimize, or even design, a website; helping organizations market themselves over social media or other online channels; and helping organizations with grant writing. In addition, some non-profits employ communication specialists of various stripes to help improve their internal communication and fundraising efforts, and sometimes these positions are filled by people with formal training in technical communication. Finally, within the academic community, there is a small, but consistent body of literature that seeks to meld the teaching and research of technical communication within academia with the goals of non-profit and other community-based organizations (Blythe, Grabill, & Riley, 2008; Crabtree & Sapp, 2004; Dush, 2014; Gonzalez & Turner, 2017; Grabill, 2004, 2007; Flanagan & Getto, 2017). What we are missing as both scholars and practitioners, however, are answers to the following research questions:

- What media do contemporary non-profit organizations typically utilize to fulfill their content goals and to reach their intended audiences?

- What strategies do contemporary non-profit organizations employ when developing and deploying various kinds of content in order to communicate with these audiences?

- How can technical communicators, content strategists, and other communication-oriented professionals help non-profits improve their content strategies?

To answer these questions, we examined the content strategies of thirteen different non-profit organizations via a series of focus groups conducted in a community within the rural American South: Greenville, North Carolina. Twenty staff and volunteers from these organizations reported to us that though they are attempting to incorporate new technologies into their content strategies, most feel unprepared to do so in a strategic manner. And having followed several of them closely since the original study, we have seen improvement in their content strategies, though we still see significant obstacles to these organizations accomplishing their content goals and reaching their intended audiences.

Below we detail the status of research on non-profit content strategy within the field of technical communication and related fields. We discuss our methodology for conducting our research. And we discuss our findings from this research, which include:

- non-profits rely on older media in favor of newer media;

- non-profits use loosely defined audiences;

- non-profits struggle to employ consistent and effective content strategies; and

- technical communicators and like-minded professionals who want to work with non-profits can help these organizations in a variety of ways.

Our chosen methodology, participatory action research (PAR), balances rigorous research investigation with intervention. It is a collaborative approach to solving problems in communities with various stakeholders. Because of this approach, one major goal of this article is to encourage technical communication researchers, teachers, practitioners, and students to use their skills as communication professionals to help non-profits. After all, as we explore throughout this article, non-profit organizations in the United States often provide needed services to a wide variety of residents from people experiencing homelessness to survivors of childhood cancer, services that are simply not available outside of the non-profit sector due to our dwindling welfare state. And as we discuss in our implications, one of the most common capacities that non-profits lack is something that many technical communicators are expert in: the ability to create an effective content strategy.

LITERATURE REVIEW: WHAT NON-PROFIT CONTENT STRATEGY MEANS FOR THE U.S. AND TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION

Providing Necessary Services

When compared to other developed democracies with stronger welfare states, non-profit organizations in the United States (U.S.) form a third sector of the economy, balancing the lack of available public services in some cases (Alexander, Nank, & Stivers, 1999; Morgan & Campbell, 2011; Pennerstorfer & Neumayr, 2017). As compared to many European countries with socialized medicine, for example, U.S. healthcare has created the necessity for non-profits that do everything for U.S. residents from providing assistance with signing up for health insurance to providing support to families dealing with spiraling medical costs (Nafi, 2019). Because of the outsized role that non-profits play in the U.S., their contributions to our way of life should not be underestimated. And though many non-profits receive public funding in the form of grants and other subsidies, this funding only accounts for 31.8% of non-profit budgets, nationally. The largest portion of funding (49%) comes from fees charged for services. In addition, donations account for 14% of overall budgets, of which individual donations are the largest portion at 8.7% (National Council of Non-Profits, 2020).

So, in a very real sense, the non-profit sector in the U.S. provides services that are heavily incorporated into the welfare state of many developed democracies. And non-profits are not guaranteed funding to do this work, meaning that they are at constant risk of losing funding and thus losing their ability to provide these services to community members. They are not unlike small businesses within our economy: they must reach various audiences and compel those audiences to action if they are to stay in operation. As opposed to small businesses whose primary focus is reaching and attracting customers, however, non-profits must also attract and retain volunteers, donors, funders, and clients to survive. At the same time, with budgets that can often shift from year to year, or even month to month, the vast majority of non-profits do not have sizable budgets for traditional advertising across older media like radio, newspapers, and television.

Technical Communication and Content Strategy

Technical communication is a wide-ranging field that encompasses many skill sets. Like related fields such as user experience design (UX), information technology (IT), and marketing, it involves a variety of strategies, practices, and professions. There have been several attempts to define technical communication as a coherent field. Like many communication-focused fields, however, these definitions remain somewhat nebulous, but include:

- a field devoted to the creation of instruction manuals and other supporting documents to communicate complex, technical information (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021);

- a field devoted to the communication of specialist knowledge to a variety of audiences using various technologies and media (Society for Technical Communication, 2021);

- a field devoted to the use of critical discourse mobilized for various types of social action (Sullivan, 1990, p. 381); and

- a collection of conceptual and practical skills paired with a flexible notion of communication (Henning & Bemer, 2016, p. 315).

For our purposes, technical communication is a field in which its researchers and practitioners have in common an expertise in communicating complex, technical information through various skills, media, and genres. This field entails such wide-ranging skill sets as:

- Writing

- Editing

- Oral communication

- Cross-functional teamwork

- The creation, publication, and distribution of various, specific genres of documentation (i.e., manuals, help guides, support forums, informational websites, etc.)

Content strategy is a diverse field that intersects technical communication in several areas, but also boasts skills, workflows, and definitions all its own. The industry literature on content strategy is extensive and comprises numerous books, blogs, reports, whitepapers, articles, online magazines, newsletters, podcasts, videos, and other digital resources, many of which are produced by consulting companies like Brain Traffic, Content Rules, Scriptorium, and Simple [A] or by websites like A List Apart (e.g., Halvorson, 2008) and the Content Wrangler (e.g., Caldwell, 2020). Among these trade publications covering the topic are several issues of Intercom (e.g., Ames, 2019; Porter, 2013; Saunders, 2019) and books such as Content Strategy for the Web (Halvorson & Rach, 2012), Designing Connected Content (Atherton & Hane, 2018), The Language of Content Strategy (Abel & Bailie, 2014), and Managing Enterprise Content: A Unified Content Strategy (Rockley & Cooper, 2012), in addition to many others (e.g., Bloomstein, 2012; Casey, 2015; Nichols, 2015; Rockley, Cooper, & Abel, 2015; Wachter-Boettcher, 2012).

In contrast, much of the recent academic literature on content strategy can be found in journal special issues that feature applied research, integrative literature reviews, and case studies (Bailie, 2019; Batova & Andersen, 2015, 2016b; Pullman & Gu, 2008; Walwelma, Sarat-St. Peter, & Chong, 2019) as well as two edited collections (Bridgeford, 2020; Getto, Labriola, & Ruszkiewicz, 2019).

Much of this collective work has been definitional. For example, Halvorson (2008) first defined content strategy as a field that “plans for the creation, publication, and governance of useful, usable content.” Bailie (2013) defined content strategy as “a repeatable process that governs the management of the content throughout the entire content lifecycle” (p. 12). Andersen and Batova (2015), defined content strategy as both “an interdisciplinary area of practice characterized by methodologies, processes, and technologies that rely on principles of reuse, granularity, and structure to allow communicators to create and manage information as small components,” and later as a “unifying approach” to “integrating organizational and user-generated content” and connecting with stakeholders, depending on its focus (Andersen & Batova, 2015, p. 242; Batova & Andersen, 2016b, p. 2). Clark (2016) traced the shifts from single sourcing to content management systems to content strategy and identified multiple industry-based definitions of content strategy.

For us, two members of the academic field of technical communication who also work sometimes as content strategy practitioners, content strategy is about:

- organizations setting realistic goals for information that is presented in a variety of formats;

- organizations thinking strategically about who is reading their content and why;

- organizations realizing that content strategy is a cyclical, iterative process that is never definitively solved; and

- organizations developing a strategic plan and vision for content.

This is also a fair summation of the field of content strategy, at least as it intersects technical communication. Many, if not most, of the scholars and practitioners cited above would likely agree that those four aims are all important to content strategy. But what do such aims mean for non-profits? We turn to that next.

Non-Profit Content Strategy

What unifies the above four aims under the rubric content strategy for us is the alignment of content goals with organizational goals. To be effective at reaching core audiences, all organizations should implement a content strategy, including non-profits. But due to many of the economic factors we mentioned above, in addition to the lack of training available for non-profit managers to learn about content strategy, many non-profits struggle to successfully adopt consistent content strategies. This doesn’t mean they lack for content, however. As Lauth (2014) points out, the content ecology of modern non-profits comprises elements such as:

- nonprofit stakeholders (i.e., donors, volunteers, employees, clients, and communities served);

- communication channels (e.g., print, websites, social media);

- devices upon which content will be encountered by core audiences (e.g., desktop, tablet, mobile);

- physical infrastructure (e.g., brick-and-mortar buildings, cloud-based content repositories, devices used to manage content);

- fundraising activities;

- needs assessments; and

- core organizational content-related processes (e.g., the development of a mission statement, the development of brand materials).

Content itself is defined for our purposes as useful information made available to at least some audiences, and may include articles, blog posts, newsletters, status updates, tweets, images, logos, videos, etc. For our purposes, the form content takes is less important than the ecology in which it exists. Non-profit organizations must strive to understand this ecology and leverage it to create useful information for their core audiences.

Here we echo many practitioners in contending, as Pope, Isely, and Asamoa-Tutu (2009) do, that “traditional marketing strategies do not work for nonprofit organizations” because their organizational goals differ from for-profit businesses (p. 184). This can also be said for communication strategy, a closely related discipline that focuses on the development of organization-wide tactics for leveraging various communication channels (Klein, 1996; Kohut & Segars, 1992; Littlemore, 2003). What sets content strategy apart from something like marketing or communication strategy is the emphasis on various forms of content, meaning information purveyed to an audience, instead of a sole focus on communication channels. One could argue that marketing, communication strategy, and content strategy only differ by their emphasis on various parts of the organizational communication situation.

What differentiates non-profit content strategy from other forms of content strategy are the specific challenges non-profits face. Nonprofits target stakeholders—which include clients, employees, volunteers, and donors—with diverse needs. Since the modern web provides nonprofit organizations with low-cost infrastructures for communicating their organizational goals to their stakeholders, non-profits need to think strategically about content management and need to integrate their users’ needs with their organizations’ mission (Hart-Davidson et al., 2008). In order to accomplish this, we argue that what non-profits really need is a non-profit content strategy that integrates a holistic approach to content, including a concrete sense of goals, channels, and audiences (Content Marketing Institute, 2016; Hart-Davidson et al., 2008; Lauth, 2014; Pope, Isely, & Asamoa-Tutu, 2009). This strategy must be mapped out and documented in written form so that all current and future stakeholders of a given organization can understand and enact the steps. As we explain in our study below, however, it’s exactly the strategy part of content strategy that serves as an obstacle for many non-profits.

METHODOLOGY: DEVELOPING NON-PROFIT CONTENT STRATEGY CAPACITIES THROUGH PAR

Our methodology for investigating and improving non-profit content strategies is PAR. PAR is a collaborative, community-based methodology that invites researchers to not only investigate problems in their local communities, but also to use their research to help intervene in these problems (Brydon-Miller, Greenwood, & Maguire 2003; Eady, Drew, & Smith, 2015; Small & Uttal, 2005; Somekh, 2006). Within the academic field of technical communication, PAR has been taken up by only a few researchers, who have used it to improve communication capacities in local communities (Blythe, Grabill, & Riley, 2008; Crabtree & Sapp, 2004). It is unclear why the methodology has not been taken up by more researchers who are doing engaged research projects with communities, especially considering the strong history of engaged research within the field. It is possible that the focus has been on developing user-centered research methodologies and paradigms rather than on adopting ready-to-hand methodologies when doing engaged research (e.g., Mara & Mara, 2015). Regardless, PAR provides a useful methodology for developing engaged research projects that focus on content strategy due to its iterative and collaborative structure.

As Somekh (2006) describes some of the core tenets of this methodology:

- Action research integrates research and action in a series of flexible cycles.

- Action research is conducted by a collaborative partnership of participants and researchers.

- Action research involves the development of knowledge and understanding of a unique kind . . . the involvement of participant-researchers who are ‘insiders’. . . gives access to kinds of knowledge and understanding that are not accessible to traditional researchers coming from the outside.

- Action research starts from a vision of social transformation and aspirations for greater social justice for all.

- Action research involves a high level of reflexivity (pp. 6–7).

In other words, PAR invites researchers to treat research participants as co-researchers in the investigation of social problems. It assumes that such research projects will be messy, collaborative, and open-ended. And it requires researchers to actively engage in self-reflexive activities during research to ensure that all research activities are equitable, just, and cognizant of power differences between researchers and participants.

METHOD

Project Background and Community Need

As with all PAR projects, this one began with a community need. In this case, in the spring of 2014 a local area non-profit director, Fernando, and a local independent community outreach specialist, Stacy, approached Guiseppe separately on several different occasions to express the need for non-profit training in effective communication.[2] This need was variously expressed as a need for help with websites, social media, and digital marketing. Through a series of conversations with Fernando and Stacy, Guiseppe realized that their expressed needs might represent a more systemic problem within the local community of Greenville, North Carolina, a mid-sized, rural city in the American South. Though the community boasts a broad array of non-profit organizations, both Stacy and Fernando strongly felt that many of their fellow non-profit professionals were largely relying on the goodwill of others to maintain their web presences.

Though Guiseppe had helped local organizations referred to him by both Fernando and Stacy, he wondered if a research project into the roots of the problem might reveal a way to help local non-profits improve their digital communication without having to work on a seemingly endless series of in-depth, ad hoc projects with each organization he encountered. Since Stacy and Fernando were enthusiastic about this prospect, in the summer of 2015 Guiseppe began developing with them a multi-stage research project that he felt would best uncover compelling findings, which they thought would best serve community needs. This project was envisioned as having three initial stages:

- Stage 1: data collection/needs assessment regarding the communication capacities of local non-profits

- Stage 2: preliminary data analysis and design of intervention

- Stage 3: deployment of intervention and assessment of impact

This loosely-bound study design was intentional as PAR projects must often be adapted on-the-fly as new community needs arise or old needs shift. Suzan would join the study partway into stage 1 as a facilitator of key moments of data collection, and would participate in various ways throughout the rest of the study, including as a workshop facilitator, data analyst, and partner on initial interventions.

In a larger sense, however, we simply don’t have enough empirical data at this point to suggest a specific approach to content strategy work with non-profits. What we do have are a few surveys of non-profit preferences regarding the use of internet-based communication technologies, both of which are somewhat dated at this point. Zorn, Flanagin, and Shoham (2010) surveyed more than one thousand non-profits in New Zealand and found that many organizations utilized tools such as email and simple databases for stakeholder engagement but had failed to successfully adopt websites as a key communication venue for reaching community audiences. The researchers tracked a variety of variables in their survey data and found that decision-maker knowledge of technology and the willingness of organizational leadership to adopt new technologies were two key predictors of the extent to which a given non-profit adopted new communication technologies. Kenix (2008), on the other hand, conducted seven focus groups across the U.S. with 52 professionals responsible for creating “internet strategy and/or web content for nonprofit organizations” (p. 407). She found that her participants largely followed a one-way dissemination model for sharing information online and demonstrated a lack of understanding when it came to developing a coherent strategy.

Data Collection

The nascent status of work on non-profit content strategy coupled with the need to assess an entire community’s needs called for a method of data collection that would assure a diverse pool of participants were recruited for research. For the purposes of generalizability, a survey design seemed most appropriate, as the largest known study to date employed this method (Kenix, 2008). When presented with this option, however, both Fernando and Stacy explained that most of their non-profit colleagues were hesitant to fill out surveys from people they didn’t personally know. Stacy suggested that “just getting people in a room together to have a conversation” would be the best way to generate interest in the study. In order to meet this community exigence while still employing a sound research design, focus groups emerged as the clear choice.

In total, three focus groups with non-profit professionals were held within the community of Greenville, North Carolina from February 2016 through April 2016 to discuss their use of digital media within their respective organizations. Focus groups were organized around a series of questions related to goals, audiences, and channels used by participants and were conducted by a professional focus group moderator hired through funding for the project, Suzan (Appendix A). Twenty staff and volunteers from thirteen different non-profit organizations were recruited from a pool of 36 organizations to discuss their use of digital media and their unmet needs for content strategy. Because existing strategies, learning needs, and organizational needs were not well understood at the inception of the study, and because the study asked participants to self-report this data during focus groups, participants were placed into heterogeneous focus groups (Stewart & Shamdasani, 2015, p. 26) via random sampling. Focus groups included six to eight individuals and engaged participants in conversations regarding existing strategies they use for digital media, organizational needs that involve digital media that are currently unmet, and new content strategies they are interested in learning.

Data Analysis

In order to uncover the status of local non-profit content strategies, the following forms of treatment and analysis have been deployed on data rendered from the three focus groups conducted to date:

- transcription of all focus group audio data into dialogue form;

- an initial coding pass to note initial themes in this data for use in later coding passes (Getto, 2017);

- use of these themes and member checks to develop and deploy a preliminary intervention in the form of a free class on content strategy for non-profits that included a free handbook on this topic for all participants (Appendix B);

- a secondary coding pass to check initial themes against the corpus of data and to ensure inter-rater reliability between the authors; and

- continual interventions in the form of ongoing educational opportunities and service-learning partnerships with local non-profits.

It is noteworthy that the final coding pass happened after the initial intervention. This is not uncommon in the practice of PAR as communities are often hungry for results. Academic research takes time to produce findings rigorous enough to warrant publication in peer-reviewed venues. At the same time, community partners’ problems are often immediate and require intervention.

PAR projects require that researchers act as much (or more) in the best interests of community members as they do in the best interests of study design. Our decision to deploy initial interventions based on preliminary findings was thus influenced by a variety of local factors. For example, due to institutional processes, the funding for the project that enabled the production of a handbook on content strategy for participants in the project was time sensitive, and only allowed for the above-mentioned forms of analysis before the intervention was deployed (Appendix B). This move to deploy interventions before final data analysis was thus a response to participant needs, several of whom had been involved with the project since its inception. As readers are no doubt aware, academic timelines often stretch stakeholder patience. Rather than achieve the level of academic rigor required of reports of research findings before the intervention was deployed, we would claim that the above forms of analysis balanced rigor with community exigences. In addition, as interventions have been ongoing largely since the summer of 2016, we have learned a lot about what our data meant in the context of the local community and our attempt to help organizations build consistent content strategies. We have a much better sense now of how the story of this project ends than had we simply relied on our focus group data without continuing contact with the local community.

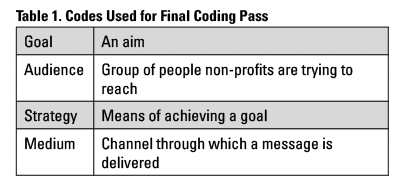

Regardless, between our initial and final coding pass, we would solidify the following codes as representative of our data (Table 1).

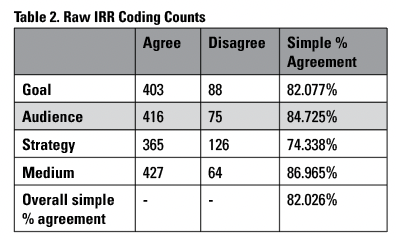

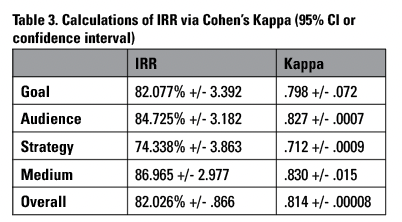

In addition, to ensure inter-rater reliability (IRR), we calculated the following using Cohen’s kappa (Neuendorf, 2017; Krippendorff, 2019) (Tables 2 and 3).

Depending on the source, 70% IRR is considered sufficient for qualitative data, so after these calculations, we were confident that our coding was in sync (Boettger & Palmer, 2010; Neuendorf, 2017).

And from this analysis, we were able to render compelling findings regarding how technical communicators can help non-profits with their content strategies. Specifically, as we explore below, we found that while non-profits do rely on a variety of media to fulfill their goals, they preferred pre-digital media. Our participants also defined audiences in a very loose manner and used content in a non-targeted way. We also found that their content strategies tended to favor existing organizational processes over content strategy best practices, which they were largely unaware of. And finally, we found that technical communicators can most help non-profits by teaching them how to better leverage their content in a holistic manner.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Non-Profit Organizations Rely on a Variety of Media to Fulfill Their Goals, but Prefer Pre-Digital Media

The first major finding from our research is that the non-profit participants of our study did use a variety of media to communicate with audiences in order to reach their goals. This media ranged from more traditional media like local news coverage to interactive websites and social media campaigns. The most common channels used by participants were as follows:

- organizational website

- news coverage

- email newsletter

- paper newsletter

- face-to-face

Nearly every participant used these six channels when communicating with core audiences, though members of a few newly established organizations had not managed to develop an organizational website yet. Only a few individuals reported using more advanced tools like website or social media analytics, and even among these individuals, it was clear they were not being used consistently or with specific goals in mind. Many paid online marketing opportunities, such as the Google for Non-Profits Grant (https://www.google.com/grants/) or paid Facebook ads to promote an organization page in order to garner donations, were largely unknown to participants.

Many participants were also skeptical of digital media, saying they preferred, in the words of one participant, media that would provide a “personal connection.” Though all participants agreed that digital media were important to their outreach efforts, most said they didn’t feel entirely comfortable using those media or even felt disingenuous doing so, like they were marketing instead of just speaking with existing and potential supporters about their cause, to paraphrase another participant. The medium most preferred amongst participants was “face-to-face,” which participants seemed to define as the act of talking to local community audiences informally in a social setting. This medium was directly referenced ten times during our focus groups, but most participants agreed with this sentiment during ensuing discussions. It was clear from many participants that they felt that digital media were the opposite of “face-to-face,” because they felt digital media didn’t allow for the informal types of interaction that they found valuable.

The main value they found in digital media was a term familiar to anyone working with non-profits: “outreach.” Within the non-profit community, the term tends to mean the act of reaching out beyond existing supporters and people currently benefiting from the non-profit’s services. The word “outreach” was used nine times within our data directly, but this idea of using digital media to go beyond a current audience of stakeholders arose many times during our focus groups. Here’s a passage from one participant that is representative:

Okay, those are domestic violence clients, trying to do an outreach with them. Letting them know that we have services. That’s always a big issue: trying to get the word out, because sometimes people don’t know, even though we’ve been here for over 30 years. And sometimes people don’t know that. So, trying to get the word out because we don’t have a budget like Coca-Cola or Budweiser to advertise during the Super Bowl. This idea of “trying to get the word out” was seen as a primary goal of adopting newer media, because traditional media were largely seen as venues for reaching existing supporters.

Anyone familiar with audience targeting within content strategy best practices probably already sees the issue with this approach to communication. Rather than zeroing in on a particular audience to target, developing content specifically for that audience, and then delivering content within the media channels preferred by those audience members, participants largely saw their content as a way to reach a nebulous public that would hopefully become aware of their message and support them. This loose definition of audience was a major issue we uncovered in our participants’ approach to content strategy and is a topic we turn to next.

Non-Profit Organizations Define Audiences Very Loosely and Largely Use a “Spray and Pray”Approach to Content Strategy

If participants saw their outreach efforts as instances in which they would hopefully snag additional supporters from a nebulous public, then it makes sense that their definition of audience was loose and ill-suited to targeting specific individuals. Below is a representative passage from a participant:

Well, our audience is anybody that lives in the community, and as far as social purpose, we like to argue that we sequester carbon dioxide, and we provide shade in the summer, which eventually we’ll need that shade to be cooling things down. We have educational programs, and we also got a grant. We got with the Dream Park and with the Community Center. The [Community Crossroads Center], which used to be called the homeless shelter, couldn’t afford their landscaping, so we provide them with landscaping, and we’re going to work with Rebuild Together this year. So, we have some social purpose, but mostly it deals with deforestation and the lack of care that our trees get, both canopy trees and understory trees in the city limits.

Like this participant, our focus group members largely saw their audience as intimately tied to their mission. Their audience was people who thought their mission was important and people who would simply see the value in their mission and become supporters. Participants also largely saw their audience as located within their service area.

Content strategists and like-minded professionals (i.e., digital marketers, business consultants, content managers, etc.) sometimes refer informally to this approach to reaching audiences as the “spray and pray” method. The idea is that if enough people are reached with a message, then they will become interested in that message purely through saturation. This approach is still promoted by traditional marketers, whose ability to target specific audiences is somewhat limited. Taking an advertisement out in a newspaper gives an organization access only to the subscribers of that newspaper and doesn’t allow for pushing a message to selected individuals within a larger group.

And like traditional marketers, our participants saw their outreach as a simple process of reaching people in the local community who think like they do. In the above example, the audience would be anyone in the local community who values planting trees. However, this approach goes against content strategy best practices, in which organizations zero in on specific audiences and create content tailored to them. Though there are a variety of components of content strategy, when dealing with audiences, there is general agreement that audiences should be specific (Abel & Bailie, 2014; Albers, 2003; Rockley, Cooper, & Abel, 2015, p. 2). Energized by digital media that provide much more specific audience targeting options, the authors of much of the literature that we cited in our literature review echo that the best practice is that content should be personalized for specific audiences. The point is not to simply put a message out to a large group of people and hope they become supportive of that message. The point is to develop a message that specific types of individuals will find valuable and will be attracted to.

Search engine optimization is a perfect example of this type of audience targeting, as people only find information through search engines when searching for keywords. So, putting content online that doesn’t take advantage of specific keywords tied to a specific audience is useless as it will never be seen by the intended group of people (Rockley, Cooper, & Abel, 2015, p. 6). Rather, content strategists who develop content for the web will typically identify search patterns that are tied to key audience demographics. In this case, the above non-profit could gather data on what local clubs are looking for when they search for service projects. Once these search patterns are identified, the challenge is to develop search-friendly content that will attract users.

This data-driven approach to content development that targets specific audiences was unknown to the vast majority of our participants. In fact, only three participants (15%) demonstrated any knowledge of audience targeting. And of these, only one participant (5%) demonstrated accurate knowledge of how to actually do audience targeting. The vast majority of participants were aware of their limitations when it came to defining audiences, however, as can be seen in the passage below:

I think it’s hard to measure communication and what’s effective and what’s not effective. Facebook, I think, sometimes we think we’re going to get more of a response than we actually do. I feel like Facebook was something that we’re trying to work on, just to build up, and get more people. In terms of ineffective, I think that it’s hard to say. Because I don’t know that we have defined communication goals. I don’t think that we have, ‘we want to reach this many people with this message or this method of communication.’ I don’t think the fact that we don’t have set goals makes it harder to measure. Or, I don’t know what the goals are because I don’t do a lot of outreach.

This participant was representative in that they appear unaware of best practices for determining effective audience targeting via a specific channel. Participants in our second group, which was populated by the sole participant who knew about audience targeting, an intern with a participant organization who also happened to be a PR major at our local university, were surprised to learn that Facebook came with an analytics suite.

Thus, it is safe to say that, like traditional marketers trying to sell ad space based on a predetermined group, our participants saw content strategy as largely a process of trial and error. Content that reached audience members and persuaded them to become supporters was seen as valuable. Content that didn’t was perhaps seen as necessary, but in a limited capacity. Of course, without hard data to support these claims, it is only natural that participants would primarily value face-to-face communication. Face-to-face communication entails instantaneous feedback from an audience. Supporters who attend an event can be given a physical clipboard to sign up for a newsletter or can make donations on the spot. They can be engaged in interactive, real-time conversations.

It is not that participants found no value in newer forms of content, such as blog posts, social media posts, and digital advertisements. On the contrary, they saw them as entirely necessary. However, they were unaware that these forms of content often allow for far more precise audience targeting than traditional media. The problem we identified early on in our data analysis was a lack of knowledge, and not one of ideology (though the two are, of course, linked). The main source of this lack of knowledge, as we explore in more detail below, was that participants largely saw their content strategies as being derived from their existing organizational processes rather than as arising from a mutually dependent process for reaching audiences.

Non-Profit Organizations Employ Content Strategies that Favor Existing Organizational Processes

When we asked participants about their content goals, they largely fell back on their organizational goals, thus conflating the two. The following passage is representative of this theme:

I think ours is to promote events. A lot of people rely on Facebook and other social media to promote their events, but if you have an event calendar on your website where it’s all mapped out for a month, I think that’s a lot more effective. Because with Facebook, you kind of announce them a couple weeks before, and that’s one thing our current website struggles with, because the events aren’t updated. Any of our board members, although it’s typically either the president or the executive director, go in and edit our website, although design and whatnot is done by somebody in our nationals. I think ours will be more effective having, on our new page, we’re going to have a scrolling event list. Because, when I’m interested in a nonprofit’s events, I look for it on their homepage to see where they’re going to be, what they’re going to be doing.

As we can see, this participant largely explains their content strategy when it comes to promoting events as driven by the existing organizational process for promoting events. There was a kind of tautology in our participants’ thinking about content goals: content was something that fit into predefined containers, containers determined by what the organization was currently doing.

Anyone who has consulted with an organization to help improve content strategy—be it in a non-profit, small business, or corporation—probably recognizes this mindset. Whenever the authors have asked an organization why they develop and deploy their content the way that they do, existing organizational processes and goals are invariably cited as the reason why content must be developed and deployed in a certain fashion. Rockley and Cooper (2012) have called these pre-existing containers “content silos” to indicate how they wall off content creators from one another within the same organization (p. 133). Like many content creators within many organizations, our participants saw existing organizational structures as necessary, permanent, and reasonable. Rather than shaping a message for their audience, they largely shaped their message around what they saw as possible within their organizations and then used this limited range of content to try to reach audience members.

The above participant says their communication goal is to “promote events,” for example. This goal puts a lot of other content in service of a pre-existing container: fundraising events. If the main organizational process of a non-profit is to host face-to-face fundraising events, then all other content should be subsumed under this goal. The problem with this approach is when it fails. There may be supporters who don’t want to attend face-to-face events. There may be audience members who remain unaware of events or aren’t available when they’re being hosted. As we write this article, COVID-19 has been making the lives of many of our existing non-profit partners very difficult for this reason. Though several of them, as we explore in the next section, have adopted more holistic strategies for their content, many others have struggled to adopt newer forms of media and thus have suffered economic losses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Technical Communicators Can Help Non-Profits by Teaching Them How to Better Leverage Content in a Holistic Manner

So far, we’ve identified several clear trends throughout all three focus groups we conducted:

- Though participants did rely on a variety of media to fulfill their goals, they had a strong preference for pre-digital media, largely because they felt digital media were less authentic.

- Participants defined their audiences very loosely and largely used a “spray and pray” approach to content in which they sent out messaging to an ill-defined group in hopes of reaching like-minded individuals.

- Participants employed content strategies that favored their existing organizational processes, often siloing their content by what media they viewed as available.

Given what we know about the status of non-profit content strategy, these trends are not particularly surprising. If, as per previous studies on non-profit digital communication, our participants were slow to adopt emerging technologies and advanced techniques for digital communication, it is only because their organizations had developed content strategies based on more traditional methods (Kenix, 2008; Zorn, Flanagin, & Shoham, 2010). Of course, material resource shortages cannot be ignored. Though we did not ask financial questions of our participants, many expressed their willingness to pay for outside consultants to assist them, if they only had the means to do so.

Regardless, given these trends, we needed to design an intervention that introduced participants to best practices in content strategy. Participants needed help learning:

- how to develop a consistent, goal-driven, organization-wide content strategy

- how to identify specific audiences for specific kinds of communication

- how to tailor messaging to specific audiences

- how to integrate this strategy across tools and audiences

Our intervention needed to educate and empower our participants to take control of their content and to think more strategically about how it is used and deployed for specific purposes.

It should also be noted that we engaged in member checks at the end of each focus group in order to ascertain whether such an intervention would be useful. Education was a key theme that emerged from these member checks, as well as from the focus groups as a whole. Participants wanted to learn how to be effective when using newer forms of media. They were aware that their organization lacked staff trained in this area and that they were potentially missing out on opportunities via their websites, social media, email newsletters, and other digital channels. Here is how one participant put it:

I think we have a lot of room to grow. I think we’re not utilizing it to anywhere close to its full potential for what we might be able to do out there, for the people we might be able to reach. We have been around Greenville for 15 years, and we have that core base of people that come to our banquet every year, they know us, but then, there are even people who come to our banquet, who have been coming every year, and if someone else asked them what Building Hope was about, they might not be able to tell you. So, I guess trying to get the message across, to reach more new people, and to be able to do that through social media, and I think that’s an avenue that would really be helpful for us. And to be able to further explain and to share the vision more-so with our donors who give because they believe in the cause, but they may not be able to explain it to anybody else, because maybe they don’t know. They just know that it’s a good organization, and they know the little tagline they hear, “Touching lives, transforming communities,” and they can re-quote that, but what does that mean? Who are we reaching? Who are we touching? Who are the kids that we’re focused on?

This “room to grow” sentiment was echoed by all participants. They were keenly cognizant of the fact that there were limitations to their knowledge and were hungry for anything that might help them reach a wider audience, and thus promote their mission to more people.

Thus, at the very end of each focus group, Guiseppe spoke for the first time after introducing the focus group facilitator and represented what he had learned by listening to participant responses to questions. In all three groups, he represented that he had learned that the biggest gap between what participants were doing now and what they wanted to do was knowledge-based. Participants universally agreed with this statement. He then proposed various solutions to this problem, including free classes offered to non-profits over the next several months on the key elements of non-profit content strategy, a free handbook on this topic that participants could take back to their organizations, and potentially the organization of an ongoing community calendar of events that would generally support non-profit management in the local community, but that would also feature ongoing events on effective communication.

Participants responded very positively to these ideas, so in the next several weeks the authors organized the first round of interventions: the development of a class called DIY Digital Marketing for Non-Profits to be offered several times over the summer when we had fewer teaching duties and the development of a free handbook of the same title that would be distributed at this event as well as online (Appendix B).

Overall, we held this course three times over the summer of 2016 and distributed 20 copies of the handbook. In the spirit of PAR, we decided to open the classes to any non-profit professional in the local community. To publicize the event, we went back to the original list of 36 organizations we had found during preliminary research and sent emails to contacts at each of these organizations. We also encouraged all participants who contacted us to spread the word to any other non-profit professionals who might be interested in attending. The classes were well-attended, given the initial sample size for the study. In total, fourteen individuals attended the class sessions. The class offered a bootcamp approach to content strategy that included guidance in each of the identified areas of need (i.e., development of overall strategy, identifying audiences, tailoring messaging, and integrating strategy across tools and audiences). At the end of each class session, we asked participants if they enjoyed the session and would attend a future session on a related topic. Participants said they would. When asked what future trainings they would be interested in, participants overwhelmingly requested tool-specific trainings, such as how to effectively utilize specific social media platforms (i.e., Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc.) and specific digital marketing tools (i.e., MailChimp, Google Ads, etc.).

As a secondary intervention, Guiseppe has also developed several ongoing service-learning classes that continue to introduce non-profits partners to content strategy best practices, to develop content and planning materials with them, and to encourage additional learning. We have also conducted several more rounds of classes and distributed our free handbook broadly. As several years have passed since the original study, we can report that many of these interventions have been successful, at least anecdotally. We have collected data along the way to attempt to ascertain the effects of these interventions on individual organizations but have had difficulty bounding this follow-up study. It is one thing to invite 20 people to focus groups to discuss what they’re currently doing. As we’ve learned, it is quite another to attempt to track the individual content strategies of dozens of local organizations.

Currently we have settled on a case study model in which we will discuss how two or three organizations adapted the knowledge we introduced them to (or failed to do so). Regardless, it is clear, at least from the overwhelmingly positive response of participants to these various interventions, that technical communicators wishing to assist non-profits with their content strategies can use similar techniques in their own communities. Whatever form they take, whether teaching a workshop, developing instructional materials, or doing free or low-cost consulting, such interventions should:

- introduce participants to content strategy best practices that are explained in a way that people without knowledge of this field can employ them;

- provide participants with written worksheets, PowerPoints, or other deliverables that they can take away with them; and

- be presented at a reduced rate or for free.

Readers of this article who are interested in doing this kind of work are encouraged to download the original handbook we developed, which we have made available for free: https://www.contentgarden.org/non-profit-digital-marketing-handbook/. To date it has been downloaded by dozens of academics and non-profit managers from around the world. Next, we conclude with a discussion of the limitations of our study and what the future holds for research on non-profit content strategy.

LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSION

Non-Profits Clearly Need Content Help, But We Need More Data

Based on our own research, as well as past research into non-profit content strategy, it seems clear that non-profits need help developing effective workflows in this area. At the same time, one important limitation of research in this area is its relative scarcity. There is so little empirical research on non-profit content strategy that it is difficult to draw broader conclusions. It is possible that participants who have responded to the calls of existing studies were the ones most in need. It is possible that there is a whole other group of non-profits out there that are doing just fine with content strategy. One has only to compare the websites of large, national non-profits like the American Red Cross (https://www.redcross.org/) or the Ronald McDonald House (https://www.rmhenc.org/) to the websites of local, regional, and thus much less well-funded, non-profits to see great disparities in content design, strategy, and reach.

At the same time, research on non-profit content strategy has not controlled for this variable: how well-funded an organization is. It seems future research in this area should attempt to compare less established non-profits with more established organizations to see if there is an effect on content strategy. It stands to reason that more established non-profits could afford to recruit better trained staff and to hire outside consultants when necessary. In our follow-up case study, we plan to compare several organizations, some of which have been around for decades and some of which were established only a few years ago. Such research could tell us much about the relationship between financial resources and content strategy. However, that research would need to account for anecdotal evidence from corporate practitioners who report that being well-funded does not automatically equal having an effective content strategy. Were that true, there would be no demand for content strategy consultants, yet, to the contrary, the need for them seems to grow more and more each year.

Despite these limitations, we believe our findings are generalizable to some degree as they match the findings of previous studies, many of which used broader recruitment methods. In addition, much of the literature we cited above on non-profit content strategy supports our findings, mainly that non-profits tend to struggle with developing consistent, effective strategies. As we mentioned above, there are also many in the field of technical communication and related fields that we have personally spoken to who actively work with local non-profits to help them improve their content strategy. We challenge these individuals to contribute more research on this area while they are doing this important service work. Those who wish to mix service with research can find a welcome methodology in PAR as it was developed to facilitate just such a mix of data collection, analysis, and active intervention.

As to the question that leads this article, the question as to what technical communicators can do for non-profits, we hope we have contributed several activities our profession can engage in to assist these organizations. We will sum up these suggestions with a simple mantra we have used over the years to help us concretize our ongoing work in this area: get involved, collect data, analyze, act, repeat. Non-profits warmly welcome anyone willing to provide them with useful service, especially if that service fills a gap that they can readily identify in their organizational strategy. The best thing communication-oriented professionals can do is collaborate with local organizations that represent causes they support. Giving money is valuable, of course, and these organizations will not continue to exist without funding. However, giving the gift of knowledge is perhaps even more impactful as it increases organizational capacities, allowing non-profits to become more self-reliant, and thus more successful in the future.

REFERENCES

Abel, S., & Bailie, R. A. (2014). The language of content strategy. XML Press.

Albers, M. (2003). Multidimensional audience analysis for dynamic information. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 33(3), 263–279.

Alexander, J., Nank, R., & Stivers, C. (1999). Implications of welfare reform: Do nonprofit survival strategies threaten civil society? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 28, 452–475.

Ames, A. (Ed.). (2019). Intercom, 66(2).

Andersen, R., & Batova, T. (2015). Introduction to the special issue: Content management—Perspectives from the trenches. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 58(3), 242–246.

Atherton, M., & Hane, C. (2018). Designing connected content: Plan and model digital products for today and tomorrow. New Riders.

Bailie, R. A. (2013). A methodology for content strategy. Intercom, 60(5), 11–13.

Bailie, R. A. (Ed.). (2019). Bringing clarity to content strategy. [Special issue]. Technical Communication, 66(2).

Batova, T., & Andersen, R. (Eds.). (2015). Transactions on Professional Communication, 58(3), 241–347.

Batova, T., & Andersen, R. (2016a). Introduction to the special issue: Content strategy—A unifying vision. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59(1), 2–6.

Batova, T., & Andersen, R. (Eds.). (2016b). Transactions on Professional Communication, 59(1), 1–67.

Bloomstein, M. (2012). Content strategy at work: Real-world stories to strengthen every interactive project. Morgan Kaufmann.

Blythe, S., Grabill, J., & Riley, K. (2008). Action research and wicked environmental problems: Exploring appropriate roles for researchers in professional communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 22(3), 272–298.

Boettger, R. K., & Palmer, L. A. (2010). Quantitative content analysis: Its use in technical communication. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 53(4), 346–357.

Bridgeford, T. (Ed.). (2020). Teaching content management in technical and professional communication. Routledge.

Brydon-Miller, M., Greenwood, D., & Maguire, P. (2003). Why action research? Action Research, 1(1), 9–28.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021, February 19). Technical writers. Occupational Outlook Handbook. U.S. Department of Labor. https://bls.gov/ooh/media-and-communication/technical-writers.htm

Caldwell, J. (2020, February 11). What storytelling means to voice and tone strategy. The Content Wrangler. https://thecontentwrangler.com/2020/02/11/what-storytelling-means-to-voice-and-tone-strategy/

Casey, M. (2015). The content strategy toolkit: Methods, guidelines, and templates for getting content right. New Riders.

Clark, D. (2016). Content strategy: An integrative literature. IEEE, 59(1), 7–23.

Content Marketing Institute. (2016). 2016 nonprofit content marketing: Benchmarks, budgets, and trends–North America. CMI. http://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/2016_NonProfit_Research_FINAL.pdf

Crabtree, R., & Sapp, D. (2004). Technical communication, participatory action research, and global civic engagement: A teaching, research, and social action collaboration in Kenya. Reflections, 4(2), 9–33.

Dush, L. (2014). Building the capacity of organizations for rhetorical action with new media: An approach to service learning. Computers and Composition, 34(2014), 11–22.

Eady, S., Drew, V., & Smith, A. (2015). Doing action research in organizations: Using communicative spaces to facilitate (transformative) professional learning. Action Research, 13(2), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750314549078

Flanagan, S., & Getto, G. (2017). Helping content: A three-part approach to content strategy with nonprofits. Communication Design Quarterly, 5(1), 57–70.

Getto, G. (2017). Helping communication: What non-profits need from content strategists. Proceedings of the 35th ACM International Conference on Design of Communication, 8, 1–9.

Getto, G., Labriola, J. T., & Ruszkiewicz, S. (Eds.). (2019). Content strategy in technical communication. Routledge.

Gonzalez, L., & Turner, H. N. (2017). Converging fields, expanding outcomes: Technical communication, translation, and design at a non-profit organization. Technical Communication, 64(2), 126–140. https://ingentaconnect.com/content/stc/tc/2017/00000064/00000002/art00005

Grabill, J. (2004). Technical writing, service learning, and a rearticulation of research, teaching, and service. In T. Bridgeford, K. S. Kitalong, & D. Selfe (Eds.), Innovative approaches to teaching technical communication (pp. 81–92). Utah State University Press.

Grabill, J. (2007). Writing community change: Designing technologies for citizen action. Hampton Press.

Halvorson, K. (2008, December 16). The discipline of content strategy. A List Apart. https://alistapart.com/article/thedisciplineofcontentstrategy/

Halvorson, K., & Rach, M. (2012). Content strategy for the web (2nd ed.). New Riders.

Hart-Davidson, W., Bernhardt, G., McLeod, M., Rife, M., & Grabill, J. T. (2008). Coming to content management: Inventing infrastructure for organizational knowledge work. Technical Communication Quarterly, 17(1), 10–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572250701588608

Henning, T., & Bemer, A. (2016). Reconsidering power and legitimacy in technical communication: A case for enlarging the definition of technical communicator. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(3), 311–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616639484

Kenix, L. (2008). Nonprofit organizations’ perceptions and uses of the internet. Television & New Media, 9(5), 407–428.

Klein, S. M. (1996). A management communication strategy for change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 9(2), 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819610113720

Kohut, G. F., & Segars, A. H. (1992). The president’s letter to stockholders: An examination of corporate communication strategy. International Journal of Business Communication, 29(1), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/002194369202900101

Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). Sage.

Lauth, I. (2014). Nine essentials of highly effective nonprofit content marketing [blog post]. http://bit.ly/1mMz2Li

Littlemore, J. (2003). The communicative effectiveness of different types of communication strategy. System, 31(3), 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(03)00046-0

Mara, A., & Mara, M. (2015). Capturing social value in UX projects. Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Design of Communication, 23.

Morgan, K. J., & Campbell, A. L. (2011). The delegated welfare state: Medicare, markets, and the governance of social policy. Oxford University Press.

Nafi, J. (2019, March 1). Top 5 non-profit organizations providing free medical care to people in need. Transparent Hands. https://transparenthands.org/top-5-non-profit-organizations-providing-free-medical-care-to-people-in-need/

National Council of Non-Profits. (2020). Myths about nonprofits. Council of Nonprofits. https://councilofnonprofits.org/myths-about-nonprofits

Neuendorf, K. A. (2017). The content analysis guidebook (2nd ed.). Sage.

Nichols, K. (2015). Enterprise content strategy: A project guide. XML Press.

Pennerstorfer, A., & Neumayr, M. (2017). Examining the association of welfare state expenditure, non-profit regimes, and charitable giving. International Society for Third-Sector Research, 28(2017), 532–555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9739-7

Pope, J. A., Isely, E. S., & Asamao-Tutu, F. (2009). Developing a marketing strategy for nonprofit organizations: An exploratory study. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing, 21(2), 184–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495140802529532

Porter, A. (Ed.). (2013). Content strategy [Special issue]. Intercom, 60(5).

Pullman, G., & Gu, B. (Eds.). (2008). Technical Communication Quarterly, 17(1), 1–148.

Rockley, A., & Cooper, C. (2012). Managing enterprise content: A unified content strategy (2nd ed.). New Riders.

Rockley, A., Cooper, C., & Abel, S. (2015). Intelligent content: A primer. XML Press.

Saunders, C. (Ed.). (2019). Content engineering [Special issue]. Intercom, 66(7).

Small, S., & Uttal, L. (2005). Action-oriented research: Strategies for engaged scholarship. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(4), 936–948.

Society for Technical Communication. (2021). Defining technical communication. https://stc.org/about-stc/defining-technical-communication/

Somekh, B. (2006). Action research: A methodology for change and development. Open University Press.

Stewart, D., & Shamdasani, P. (2015). Focus group: Theory and practice. Sage.

Sullivan, D. L. (1990). Political-ethical implications of defining technical communication as a practice. Journal of Advanced Composition, 10(2), 375–386. https://jstor.org/stable/20865737

Wachter-Boettcher, S. (2012). Content everywhere: Strategy and structure for future-ready content. Rosenfeld Media.

Walwelma, J., Sarat-St. Peter, H., & Chong, F., (Eds.). (2019). IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 62(4), 315–407.

Zorn, T., Flanagin, A., & Shoham, M. (2010). Institutional and noninstitutional influences on information and communication technology adoption and use among nonprofit organizations. Human Communication Research, 37(1), 1–33.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Guiseppe Getto is an associate professor of technical and professional communication at East Carolina University. His research focuses on utilizing user experience (UX) design, content strategy, and other participatory research methods to help people improve their communities and organizations. He co-edited the book Content Strategy in Technical Communication, and his research has appeared in leading publications in the field of Technical Communication. Read more about him at: http://guiseppegetto.com. Contact: gettog@ecu.edu

Suzan Flanagan is an assistant professor at Utah Valley University where she teaches technical communication, editing, and collaborative communication. Her research focuses on technical and professional communication at the intersections of editorial processes, content strategy, and user experience (UX). She co-edited Editing in the Modern Classroom (Routledge, 2019) and is currently researching best practices in mobile UX design and the state of content strategy practitioners. Contact: sflanagan@uvu.edu.

APPENDIX A: Focus Group Script

- How Your Organization Communicates

- Who are the people in the community that you are trying to reach through your organization?

- What are all the ways you communicate with these audiences?

- Which of these ways of communicating do you find to be the most effective, and why?

- Which of these ways of communicating do you find to be the least effective, and why?

- Organizational Websites

- How many of you have websites for your organizations?

- If you have one, what do you most like about your organization’s website?

- What do you most dislike about it?

- If you don’t have a website for your organization, why is that?

- Who are the people you are trying to reach with your organization’s website?

- What feedback have you gotten, if any, from visitors to your organization’s website?

- What would you like your organization’s website to do for your organization and for the people you are trying to reach?

- Social Media

- How many of you use social media as an organization?

- What social media platforms do you use (i.e., Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, etc.)?

- What do you most like about your organization’s social media?

- What do you most dislike about it?

- If you don’t use social media as an organization, why is that?

- Who are the primary audiences for your organization’s social media?

- What feedback have you gotten, if any, from audiences you interact with on social media?

- What would you like social media to do for your organization?

- Goals For This Research Study

- What made you sign up for this research study? What do you hope to get out of participating?

- What unmet service or programmatic needs do you have that you think might be met through the use of online media?

- How do you plan to meet those needs?

- What kinds of educational opportunities would you be most interested in participating in as part of this study? What do you most hope to learn through this study?

APPENDIX B: Digital Marketing Handbook

[1] To our knowledge, there has been no formal research study of technical communicator volunteer habits. From talking to many technical communication practitioners over the years, however, we have anecdotally heard many stories of volunteer work with non-profits that focus on their professional skill sets. Academics who research and practice technical communication tell similar stories of volunteer work with non-profits. Whenever we aren’t able to cite formal research throughout this article, then, we are relying on this anecdotal experience that goes back about 20 years of combined work in this area.

[1] To our knowledge, there has been no formal research study of technical communicator volunteer habits. From talking to many technical communication practitioners over the years, however, we have anecdotally heard many stories of volunteer work with non-profits that focus on their professional skill sets. Academics who research and practice technical communication tell similar stories of volunteer work with non-profits. Whenever we aren’t able to cite formal research throughout this article, then, we are relying on this anecdotal experience that goes back about 20 years of combined work in this area.

[2] Participants’ names have been changed to protect their identities as per their request.