doi: https://doi.org/10.55177/tc350749

By Rachel Martin Harlow

ABSTRACT

Purpose: This research is the first step in exploring how public policymakers use the expert knowledge and nonexpert knowledge they acquire in oversight hearings. This step is focused on learning what the testimony in oversight hearings reveals about how the primary stakeholders of the February 2021 power loss event understood that event.

Method: The researcher used NVivo, a content analysis application, to examine public comments, witness testimony, and a combination of legislators’ press releases and the text of bills they drafted. All texts were generated in February and March 2021. The researcher ran both a word frequency analysis and a thematic analysis of each set of texts to identify topoi used by each stakeholder group and compared the results.

Results: The analysis revealed that the three primary stakeholder groups perceived the February 2021 power loss event differently, though some of the most salient, significant, or urgent concerns of each group overlapped. The stakeholder groups shared some topoi, but the ways each group used those topoi suggested different ways of understanding and interpreting the event.

Conclusions: Technical communicators who are tasked with reconciling technical and nontechnical audiences in situations like this can use the techniques discussed here to better identify specific places where the respective groups’ use of topoi diverged from one another or aligned with one another. The more that is known, and not just surmised, about stakeholders and how they understand and interpret their technical knowledge, the better we can address how that knowledge may be communicated throughout the legislative process.

KEYWORDS: content analysis, public policy, topoi, expert knowledge, nonexpert knowledge

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Technical communicators who work in public affairs or public policy are often called to reconcile public knowledge with diverse areas of technical expertise.

- Multiple stakeholders may use the same topoi but understand and interpret those topoi differently.

- Automated content analysis of large sets of textual data can use topoi to identify areas of overlap and difference in how stakeholders interpret public policy communication.

INTRODUCTION

In early February 2021, all of Texas was watching the weather. The National Weather Service predicted the advance of Winter Storm Uri, a frigid air mass that was expected to linger over the state for days, bringing below-zero temperatures, freezing rain, and heavy snow to a state unaccustomed to severe winter conditions. Among the many state agencies warning citizens of the impending storm were the Public Utility Commission of Texas and the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), a non-profit entity that “works with those utility providers to manage the flow of power to about 90% of the state” (Menchaca, 2021). Officials at these agencies expected “demand for electricity . . . to hover just below the record demand typically seen in the summer,” though many of the state’s available generators and power plants were offline because of lower winter demand (Menchaca & Ferman, 2021).

The storm was worse than expected. Governor Greg Abbott issued a disaster declaration on February 12 and deployed state resources to protect life and property, while ERCOT and the Public Utility Commission made increasingly urgent calls for Texans to conserve energy as much as possible (Public Utility Commission of Texas, 2021). The U.S. Energy Information Administration (2021) reported net electricity generation on the Texas power grid:

Fell below ERCOT’s day-ahead forecast demand shortly after midnight on February 15, and that trend persisted through February 18. The mismatch between demand and day-ahead forecast demand quickly grew to at least 30,000 megawatts (MW) on February 15 before eventually narrowing to slightly less than 20,000 MW by February 17 (February 19).

For over a week much of Texas was shut down and shivering in the cold and dark. The Texas Tribune predicted short-term rolling blackouts following ERCOT’s emergency plans; the actual blackouts ranged from a few minutes to days, depending on the capacity of individual electricity providers, and the cold and blackouts caused water supply and quality problems. One could hardly blame Texans for dubbing the event “Snowpocalypse” and “Snowmaggeddon,” for “many people lacked internet access, cellphone service and the ability to watch the governor’s press conferences. When the power went out, the state suddenly lost the ability to provide essential information to people desperately in need of help” (Agnew, 2021). The crisis was acute, both in its severity and its duration, for by February 19, ERCOT lifted emergency conditions. As far as power generation and transmission were concerned, the crisis had passed.

The reckoning, however, was swift in coming. Within a week the governor and key committees of the Texas Legislature called for investigative hearings to determine the cause of failures mechanical and administrative. In the Texas House of Representatives, the Committees on Energy Resources and State Affairs called representatives from ERCOT, from the Public Utility Commission of Texas, from public-private councils and lobbying groups, and from power generation and transmission entities all over Texas to testify at a joint public hearing on February 25 “to consider the factors that led to statewide electrical blackouts during the recent unprecedented weather event; the response by industry, suppliers, and grid operators; and changes necessary to avoid future power interruptions” (Paddie, 2021). That hearing recessed well past midnight and was concluded on February 26. At the same time, the Texas Senate Committee on Business and Commerce held its own public hearing, the purpose of which was more narrowly focused on examining “extreme weather condition preparedness and circumstances that led to the power outages as directed by Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT).” The committee also intended to “review generator preparedness and performance, utility outage practices, natural gas supply, and the reliability of renewable generation, as well as overall ERCOT system resilience” (Hancock, 2011). A second Senate hearing, later canceled, was scheduled for March 4 by the Committee on Jurisprudence to:

Examine the legal responsibilities that the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) and the Public Utility Commission of Texas (PUC) owe to the people of Texas. The committee will review the legal framework for governance and oversight of these two entities, their relationship to one another under the law, potential legal liabilities, and the legal limits on increases to consumer electricity rates during an emergency. The committee will also examine price gouging under the Texas Deceptive Trade Practices-Consumer Protection Act and receive an update from the judiciary on how the judicial system is managing its operations during the ongoing statewide emergency. (Legislative Reference Library of Texas, 2021)

In the weeks following the hearings, the three commissioners of the Texas Public Utility Commission resigned. Dozens of bills were drafted and introduced in the Texas Legislature; as of the end of the regular session, 10 bills relating to electricity regulation had been engrossed, or advanced from one legislative chamber to the other for consideration. Thus, the effects of the February 2021 power loss event following winter storm Uri continued to ripple through state politics as the Legislature moved to the end of its regular session. This unfolding situation provided an opportunity to explore what public policymakers do with the information they acquire in oversight hearings. Such information is a combination of expert knowledge and nonexpert knowledge, any of which may contribute to the “envisioning and redirecting” of public policy (Rude, 1997, p. 78) in the midst of a response to an ongoing crisis.

Technical communicators who work in industries subject to public oversight, such as the commercial power industry, must negotiate complex audiences composed of legislators, industry experts, and the public—stakeholder groups whose interests may both conflict and converge. Stakeholder groups like these consist of people who share a common interest, or stake, in an issue and who share information about that issue. Three primary stakeholder groups emerged in the hearings following the Texas power loss event of February 2021: the public, legislators, and industry witnesses who testified at the hearings. The present study thus focuses on addressing the following question: What do variations in topoi used in the testimony in oversight hearings reveal about how the primary stakeholders of the February 2021 power loss event understood that event?

Over time, stakeholder groups develop patterns of language and reasoning, or what rhetoricians call topoi, that include words used or defined in specific ways; figures of speech, recognizable stories, and familiar analogies, all of which serve as shortcuts or heuristics for more fully developed arguments and positions. While some topoi are unique to a specific group of stakeholders, others may be held in common with other stakeholder groups (Ross, 2013). Moreover, some topoi may appear to be shared by different stakeholder groups, but actually represent very different ways of understanding the issue (Bormann, 1985). While these groups may use the same language to express their respective interests, it is important for technical communicators to understand the nuances of the way each group understands and interprets that language.

TESTIMONY IN OVERSIGHT INVESTIGATIONS: A REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Public policy is a technical or specialized field that produces information, processes that information into knowledge, and uses that knowledge to inform practice (Williams, 2009). Its complexity is compounded by the fact that it is concerned with a wide variety of other technical and specialized fields, from finance to medicine to civil infrastructure. Following a crisis, researchers often examine how technical communication is used in oversight investigations, both those that seek to determine the underlying cause(s) of the crisis and policy changes that might be undertaken to resolve it. Winsor (1988) and Moore (1992) explored the relationship between organizational communication practices with respect to technical information within public testimony. Shaffer (2017) used the transcripts of an oversight hearing to explore how cognitive load affects individual legislators. Numerous scholars, including Youngblood (2012), Dragga and Gong (2014), Lancaster (2018), and Lundgren and McMakin (2018) have explored the communication of risk around such events. The overwhelming focus of post-crisis communication seems to be on organizations’ public relations efforts (Arendt, LaFleche, & Limperopulos, 2017), particularly image repair and reputation management efforts directed toward the larger public (Benoit, 1995; Coombs, 2004; Coombs & Holladay, 2002; Drumheller & Kinsky, 2021; Ma & Zhan, 2016). In recent years increasing interest has turned to the role of social media in such efforts (Austin, Liu, & Jin, 2012; Wendling, Radisch, & Jacobzone, 2013).

In the context of public policy, technical communicators must do more than simply translate expert knowledge to non-experts; rather, they must reconcile specialized and common knowledge, or find some agreement between what experts say and what lay audiences in the public think. Some research in the differences between expert knowledge and nonexpert knowledge has been done (Boswell, 2009; Carlton & Jacobson, 2016; Christensen, 2021; Coles & Quintero-Angel, 2018; Lundin & Öberg, 2014), but more is needed, particularly in the degree to which policymakers incorporate both into the legislation they write. This need is most clearly demonstrated in public hearings, wherein legislatures call upon both experts and the public to testify. In the U.S., many legislative bodies, including Congress and state legislatures, are authorized to conduct such hearings. Frulla (2012) explains that such hearings fall into two classes: legislative investigations, in which experts and members of the public are called upon to inform the development of public policy, and oversight investigations, which are held to review how the legislative body’s laws are carried out or to hold major corporations or other entities accountable for their actions in and responses to a major crisis (p. 375).

Research on legislative and congressional testimony thus far has considered primarily legislative investigations (Chapman, 2020; Evans & Narasimhan, 2020; Marvel & McGrath, 2016), and research in technical communication has argued that the collected weight of such testimony actually does influence legislators’ decision-making (Rude, 2004), particularly when it includes data and information presented by individuals whose credibility derives from knowledge or expertise (Moreland-Russell et al., 2015, p. 95). In legislative hearings, reports and other forms of testimony may have quiet but far-reaching effects in the organizational construction of knowledge, as the language they use reflects a specific way of perceiving, reasoning about, and understanding an issue, that, if adopted by lawmakers, may ultimately influence how the public perceives, reasons about, and understands that issue.

Oversight investigations are a type of legislative hearing, generally called in response to a crisis or other exigence, in which the reconciliation of technical and public knowledge is especially urgent. Oversight investigations “tend to be more confrontational, intrusive, and fraught with risk exposure (reputational, regulatory, criminal, economic)” than legislative investigations (Frulla, 2012, p. 374). Moreover, such investigations are performed or enacted in a complex rhetorical space that is both “institutionally complex (i.e., procedurally dense) and technically and scientifically complex” (Simmons & Grabill, 2007, p. 423), and yet open to the public. Legislators use this space to enter into public record highly technical testimony that also must be relatively accessible to a complex audience of experts, informed non-experts, and uninformed non-experts. The testimony may be delivered in a variety of forms or media, as Rude (2004) suggests, and whether the testimony is delivered as a formal report, oral statement, response to questioning, or prepared visual, it is “a tool of strategic action,” and an “active address to a complex audience that does not reside in one place at one time” (p. 283). This audience includes not only the legislators holding the hearing, who must be persuaded “of the merits of the argument” offered as testimony, but also members of the press and of the broader public who might act on this information well into the future (p. 283).

METHOD

Contemporary oversight investigations generate a staggering amount of text, audio, and video, and while each individual item entered into the record may be of limited significance, it is the combined weight of these items that affects public policy (Rude, 2004). A substantial and growing body of research has been focused on analyzing large data sets through content analysis and text mining methods (Frith, 2017; Graham, 2015; Lam, 2016). In quantitative content analysis statistical methods are applied to textual data to identify relationships between ideas, meanings, and the context of a corpus of data (Riffe et al., 2019, p. 23), while qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis explore meaning as it is embedded and expressed in the data. Both forms of content analysis are time-consuming when done by hand on even small data sets; for large data sets these methods become highly problematic. However, researchers can now use robust text mining software that does content analysis using sophisticated algorithms to analyze unstructured text (Allahyari et al., 2017), as well as video, audio, and multimedia sources (Karaa & Dey, 2017).

The current study used NVivo, a text mining and content analysis application, to analyze the 2021 power loss event hearings using both frequency analysis (quantitative) and thematic analysis (qualitative). Frequency analysis relies on the assumption that the more often a word or a family of related words appears in discourse, the more important that word or family of words is to those who use it. In contrast, thematic analysis looks not only for conceptual relationships between individual words but also among ideas, phrases, and figurative language (Vaismoradi & Snelgrove, 2019). The mixed-methods approach is useful in determining not only the words associated with specific topoi but also the concepts, figurative language, and logic associated with them.

To complete the frequency analysis, the researcher ran a word frequency query that counted the frequency of words of 3 or more letters and that grouped exact matches, stemmed words, synonyms, and specializations. This word frequency query was cast with intentionally broad parameters, as rhetors tend to use topoi as shortcuts or heuristics for more fully developed arguments and positions, assuming that others will interpret those topoi just as they do.

Because an automated frequency analysis may miss implicit associations between ideas, concepts, and experiences that may be unique to each stakeholder group, the researcher also conducted an automated thematic analysis of the texts associated with the three stakeholder groups involved in the oversight hearings. This thematic analysis identifies noun phrases and sentence-level patterns of repetition associated with those noun phrases. The application weighed relative significance of each theme in each item and across all the items in the analyzed set, then grouped the themes into broader categories of ideas.

The researcher then compared the 20 most frequently used word families from the frequency analyses and the 20 most prominent themes from the thematic analyses for each stakeholder group to understand how each stakeholder group viewed the power crisis event. The third stage of the analysis involved comparing the most important themes, as measured by the frequency with which they appeared in the records, across all three stakeholder groups. This comparative analysis can reveal not only points at which “different interpretive communities focus cognitively and rationally on different elements of a policy issue . . . because they value different elements differently,” but also differences in how the respective groups’ values “conten[d] for public recognition and validation” (Yanow, 2000, p. 11).

Data Sets

On February 25 and 26, 22 witnesses were called to testify before a joint session of the 11 members of House Committee on Energy Resources and the 13 members of the House Committee on State Affairs, a process that produced over 25 hours of oral testimony, both in person and virtual. Also, on February 25 and 26, 26 witnesses were called to testify before the Senate Committee on Business & Commerce. This hearing, independent of the House Committee hearing, produced over 23 hours of oral testimony. Both hearings were broadcast live. Many of those witnesses also submitted written testimony for the public record. Because of public health restrictions implemented as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, only individuals invited to provide testimony were permitted to attend the hearings, and public comment was sought through a written medium, rather than oral testimony.

The current study classified data drawn from these hearings into three sets: public comment, legislator, and witness. All the documents examined in the current study were created in February and March 2021, though the timing of the three data sets varied slightly. For example, public comment in the Texas House was open before, during, and after the oral portion of the hearings, while most of the legislation was proposed in the month following the hearings. In addition, the data sets varied in size and composition; the text of bills, for instance, is highly technical and specialized, while the public comments include a mix of expert and non-expert communications, some formal, some informal.

Public comment data set

Public comments for the Senate were collected through an e-mail form on the Texas Senate’s web site but are thus far unpublished. Public comments from the House public comment database were entered into the House record as testimony on March 1, at which point well over 8,000 comments were recorded. Current research, including studies by Bogain (2020), Cheng and Jin (2019), Gallagher (2020), George and Hovey (2020); Kalogeropoulos et al. (2017), Muddiman and Stroud (2017), and Taylor et al. (2016), have explored the content of online posts to comment boards as a useful source of information about the attitudes, opinions, and experiences of members of the public, despite real concerns about how well such comments represent the full range of public experience. The Texas Legislature’s two public comment access points are and have been accessible to the public for years and were shared with the public by means of notices of public hearing that were picked up by local news outlets as early as February 22. In the public notice of the committee hearings, the House set the deadline for public comment at noon on March 1, 2021.

Legislator data set

The concerns of legislators were explored through two types of documents: press releases and the language of proposed legislation. Because these two genre differ significantly in scope, audience, and purpose, they were analyzed separately.

Press releases “play a significant role in the production and framing of news,” and as such are important because they function as “information subsidies,” or a means by which practitioners interpret the information provided to journalists through selection, emphasis, and omission of certain attributes out of all that is available about an issue or event (Lee & Basnyat, 2013, p. 122). Thus, press releases can be used to represent how legislators would prefer the public to interpret a given issue or situation. Between February 17, 2021 and the end of the regular legislative session on March 30, 2021, various members of the Texas House of Representatives and the Texas Senate published press releases related to the Texas electricity industry, regulators, and related legislation on the web sites of the House and the Senate.

Press releases are not the only means by which legislators leave a record of their specific concerns related to an issue. Of the 7,548 bills filed in the 87th Legislature Regular Session by the March 12 deadline, over 400 related to energy, electricity, or public utilities, and 277 were related to the 2021 power event.[1] The language used in these bills reflects not only the legislative and legal positions of their authors, but also how the writers of each proposed bill understood and interpreted the February power event, both in terms of the justification offered at the beginning of each bill and in terms of the legal response they considered appropriate and acceptable to their constituents. It is far from uncommon for legislators to file multiple bills that propose action on a single issue, knowing that the redundancies and conflicts will be resolved in committee. Those who study public policy as a technical or specialized field recognize that the initial filing of a bill is a complex form of technical communication that must conform to very specific requirements of format, language, process, and technical detail, but also serves as a medium of communication between a legislator and their constituency in which the legislator may acknowledge or address the way they believe their constituents interpret a specific problem.

Witnesses data set

To fully understand how the three primary stakeholder groups understood and interpreted the February 2021 power events, the testimony of the witnesses cannot be ignored. The 26 witnesses who were invited to testify before the joint hearing of the House Committees on Energy Resources and State Affairs and before the hearing of the Senate Committee on Business and Commerce represented a variety of stakeholders, including industry interest groups and lobbying organizations, for-profit power generation and distribution companies, electric cooperatives and municipal utilities, regulatory agencies and public-private coalitions, hydrocarbon producers and distributors, renewable energy producers and distributors, a telecommunications company, and the not-for-profit electrical grid operator.

Most of the data to be drawn from witness testimony is contained in over 23 hours of video recordings, transcripts for which have not yet been generated. However, many of the witnesses also submitted written testimony to the oversight hearings. Thus, the corpus of data analyzed in this study includes both the written testimony that was submitted to the House Committees and published online and the summary of testimony included in the Senate Committee on Business & Commerce Interim Report to the 87th Legislature (2021). On the Senate side, the summary of oral testimony was written by the committee; while the actual documents submitted as written testimony have not been published, it is likely that the documents submitted by those witnesses who testified before both the House and the Senate hearings were similar or identical to one another. On the House side, no summary of oral testimony is available and not every witness submitted written testimony; however, the documents that were submitted have been published and are available to the public. Consequently, this corpus constitutes a much smaller and less uniform data set than those of the other stakeholder groups. Future research will be able to strengthen this corpus with data from oral testimony.

ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

Frequency Analysis

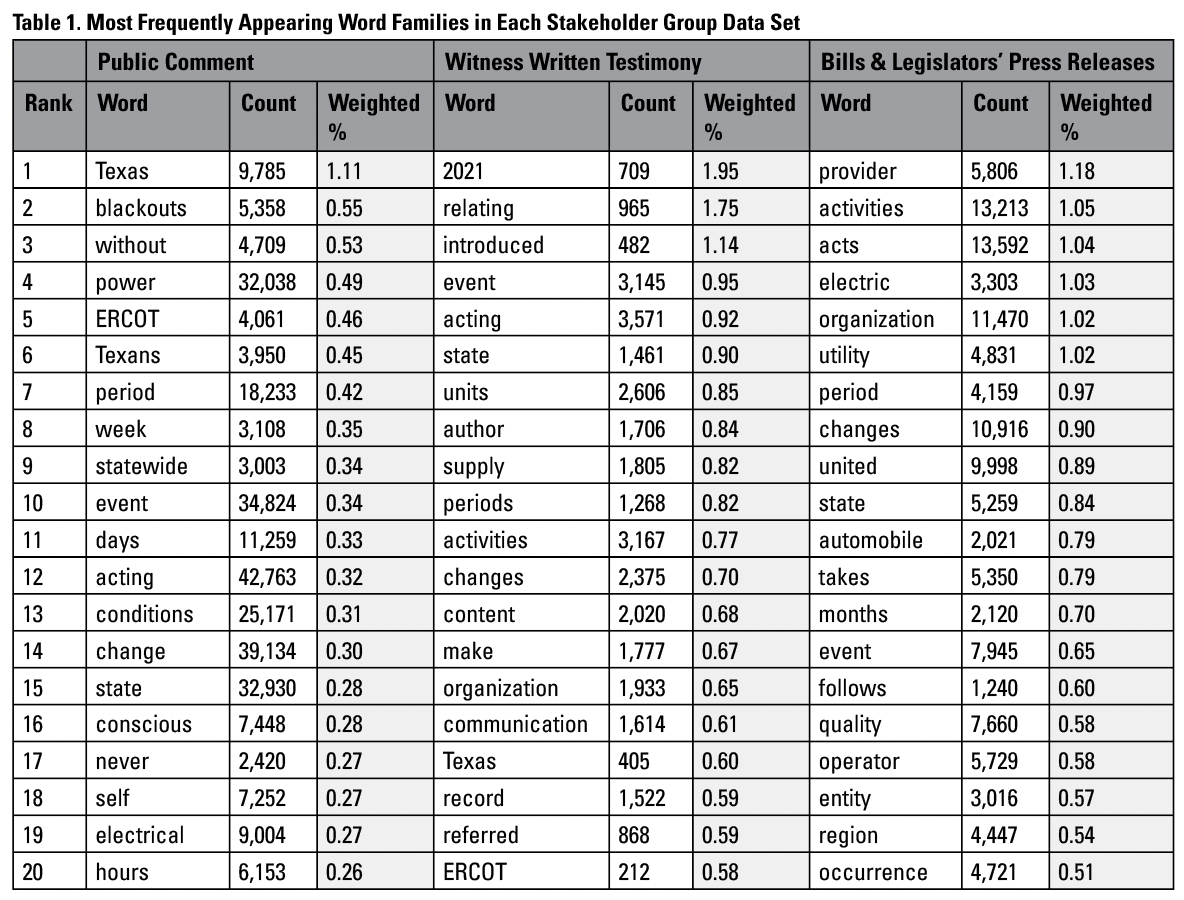

The results of the frequency analysis are summarized in the table below, which identifies the 20-word families that appeared with the highest frequency in each data set. The word families noted in Table 1 are categories, rather than individual words. The event word family, for example, groups words that characterize or are related to events together under one label. The table shows not only the actual number of items counted within each word family but also the word family’s weighted percentage, which compares the frequency of the word against the total number of words counted. This weighted percentage accounts for similar words that may be coded as part of more than one word family.

Finding patterns of related words in a large sample of texts can reveal the topoi that are held, or at least recognized, by members of the group. Again, for the purposes of this study, the frequency of a topos functions as a proxy for its importance. A shortcut or heuristic only becomes a topos when it encapsulates a widely shared way of understanding the world. The most important, most useful, most shared topoi, then, should appear more often in the testimony.

Time topoi

In this study, time was an evident concern of all three stakeholder groups, though the ways in which they expressed time differed. The general term period appeared within the top 20 most frequently used words in the frequency analysis. In addition, the public articulated time concerns in units of immediacy (week, days, and hours), consistent with the acute nature of the power loss event. Legislators articulated time concerns in terms of months. Though the laws they negotiate are designed for extended use, Texas’s biennial legislative sessions meet for five months out of every 24-month period, a cycle that may affect how legislators perceive time. In contrast, witnesses’ specific references to time are largely about a single year, 2021. As the oversight hearings took place in February 2021, it is likely that the witness texts are either narrowly focused on the week of the power loss event or project actions into the remaining ten months of the year.

Entity topoi

Many of the most frequently used word families identified in the frequency analysis characterized or related to each stakeholder group’s perception of entities, or groups of people bound by membership relationships. The legislator stakeholder group mentioned entity frequently, along with provider, operator, and unity. The witness and legislator stakeholder groups made frequent mention of organization, while the witness and public groups identified ERCOT (the Electric Reliability Council of Texas) as an entity—the witness texts specifically identified ERCOT 202 times, while the public texts did so 4,061 times. It is the only named entity in the 20 most frequently used word families of each of the three stakeholder groups. The grid operator was key to how the public and the witnesses perceived the power loss event, and interestingly, the frequency with which the public named ERCOT suggests that the word served not only to identify a specific government agency. A brief examination of both the witness testimony and the public comments suggests an intriguing distinction in the way these two stakeholder groups use the term ERCOT. While the witnesses use the term to refer specifically to the Energy Reliability Council of Texas, the public seems to use ERCOT as a shorthand reference to the entire electricity industry and the state agencies that regulate it, a topos that depends on synecdoche (a figure of speech and writing in which a part represents the whole). This suggestion is beyond the scope of the current study, but it merits additional research.

Location and membership topoi

Closely related to the entity topoi are those in which location and membership were connected. Word families that characterize or are related to geography, such as region and state, were frequently used by all three stakeholder groups in reference to geographical jurisdictions.[2] Witnesses tended to use geographical terms literally, consistent with their interests in physical locations and areas, while the public and legislator stakeholder groups used some geographical terms figuratively. For example, Texas was often used as a metonymic reference to the people of Texas as well as to the political entity.

Event perception topoi

The frequency analysis also provides some insight into how each group perceived what happened during the week of February 14–21, 2021. The public stakeholder group used words that characterized or were related to event, blackouts, statewide, conditions, along with hours, days, and week. This group, it would seem, understood the power loss event as something a group experienced over a specific time. Witnesses used words in the event word family also, but the overall emphasis was on supply, units, and activities, indicating a more technical understanding of the power loss event. The word families most prominent in the legislator lists, such as acts, occurrence, operator, event, provider, and organization emphasized agents and actions. Given that the oversight hearings called forth agents to testify about those actions, these topoi suggest that the legislators perceived the events in terms of responsibility: who was responsible for normal electrical grid operations and who was responsible for the failures thereof.

Future research may find additional points of interest in this data set through sentiment analysis, a subset of text mining that focuses on identifying the valence, or emotional content, of unstructured text (Cambria et al., 2017). The most clearly negative word families in the frequency analysis are blackouts, without, and never, all of which appear in the public list. Neutral word families dominate both the witness group and the legislator group. The public, who suffered most from the power loss event, might be expected to perceive the event more personally and negatively than either of the other two.

Three word families generated by the content analysis application should be viewed with some circumspection: self in the public list, and act and takes in the legislator list. The self word family includes references to one’s own person and experiences; it is also related to the conscious word family, which includes terms about self-reflection and ego and frequently is used to acknowledge the context of a complaint. However, self is also a term used on the House Public Comment form to denote on whose behalf the form is being submitted, so it appears with much more frequency than it would in natural language. This specific use may skew the results of the frequency analysis. Similarly, the term act has a specialized use in legislation, as every bill is introduced as “An Act to be Entitled” until it is given a name, and every bill begins with the language “Be it enacted.” Though the word act itself was excluded from the frequency count and the application coded acts and activities separately, words related to acts or acting may yet be overrepresented in the legislative stakeholder data set. The takes word family is problematic for a different reason: the words coded as part of that family seem less related to one another than other word families. The word family breaks apart at a more restrictive level of analysis, which suggests that another round of more targeted coding may be needed to determine what, if any, insights the word family might offer.

Thematic Analysis

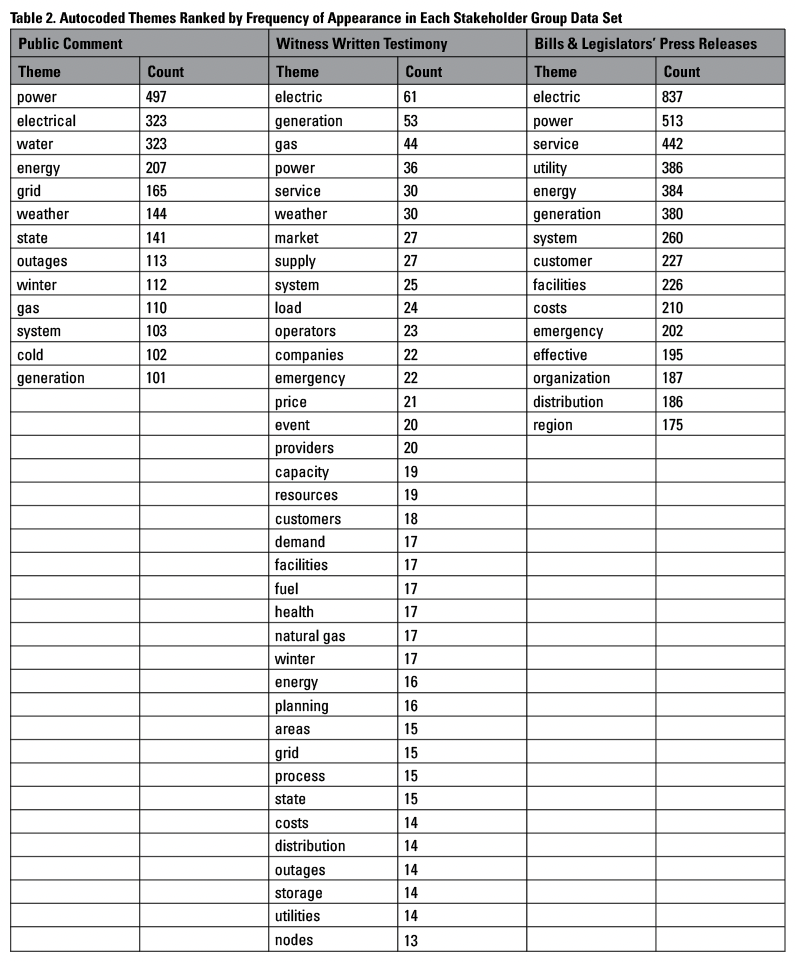

The results of the autocoded thematic analysis are summarized in Table 2. The content analysis application used an iterative process to identify distinct themes or topics at the sentence level, rather than at the word level (as in the word frequency analysis). This analysis was not limited to a specified number of themes but lists all themes generated and the frequency with which they appeared in each data set.

The most noticeable difference between this analysis and the word frequency analysis is the format of the results. A total of 37 distinct themes emerged from the witness stakeholder group texts, while 15 emerged in the legislator group and only 13 emerged from the public group. A greater number of themes indicates that more distinct topics were addressed in the texts; fewer themes mean the texts were more focused on fewer ideas or concepts.

Unsurprisingly, most of the themes coded in the witness data set related to the generation, transmission, and delivery of electrical power. The diversity of themes among witnesses’ written testimony indicates that the data set includes significant amounts of technical detail and that this stakeholder group distinguishes concepts in ways the other two groups might not. In addition to technical themes related to the generation and distribution of electricity (such as load, capacity, generation, grid, distribution, outages, and nodes), themes related to the business of electricity (service, market, supply, demand, customers, companies, price, resources, and costs) also emerge. The themes that emerged in the legislator data set tended to be less technical in nature and more aligned with the business of electricity, which is consistent with the role the Legislature has taken toward regulating the electricity industry in Texas (Price, 2021). In contrast, themes that were most strong in the public stakeholder group were related to personal experiences caused by the power loss event: weather, winter, and cold. The themes highlight the interrelated nature of public utilities, as well since the loss of power or electricity led to blackouts and problems with electricity-dependent water and gas utilities.

There was less overlap between coded themes than between word families in the frequency analysis. Only four themes, electric(al), generation, power, and system, were coded in all three data sets, and three of those themes are inherently related. It is interesting to note that only themes for electricity generation were common to all three groups; distribution is a theme in the legislator and witness data sets but not the public data set.

Infrastructure is included in the more general facilities theme in the legislator data set and is treated in a much greater level of detail in the witnesses’ written testimony, even though that data set is much smaller. Furthermore, the results of the thematic analysis suggest that the witness stakeholder group understood and interpreted the power loss event more similarly to either of the other two groups than those groups did to one another. Of themes that showed up in two data sets, only 4 of the 13 themes found in the legislator data set are also found in the public data set, while 11 of 13 themes found in the legislator data set are also found in the witness data set, and 11 of the 13 themes found in the public data set were also found in the witness data set.

Taken together, the word frequency analysis and the thematic analysis of the two oversight hearings revealed that the three stakeholder groups used certain topoi with relative consistency, while others (such as ERCOT) indicated very different ways of understanding the February 2021 power loss event. It is to be expected that some of the most salient, significant, or urgent concerns of each group would overlap; after all, some legislators and witnesses also experienced hours or days without power, heat, and water. Technical communicators who are tasked with reconciling technical and nontechnical audiences in situations like this can use the techniques discussed here to better identify specific commonplaces where the respective groups’ perceptions of the event diverged from one another or aligned with one another.

Snowpocalypse 2021 was an acute crisis: serious while it lasted, but resolved relatively quickly. In fact, by the time the data for this research project was gathered and analyzed, the crisis was over for most people affected by it. Power had been restored to most of the state within a week, water pipes were repaired or replaced over the following month, and legislators winnowed down the legislation proposed in response to the event. For communicators working through a longer crisis, such as the 2019-2021 COVID-19 pandemic, or for communicators working on chronic or systemic problems in public sphere, using automated content analysis of large, disparate data sets can reveal how various stakeholders perceive issues and express those perceptions through language. Thus, this approach can be a useful tool for technical communication in the public sector who work to reconcile public and technical knowledge from disparate areas of expertise.

FUTURE RESEARCH

Future research projects may add richness to the current analysis by adding to the existing data sets the transcriptions of the oversight hearings as they become available. The questions that committee members raise and the comments they advance in the oral portion of the hearings may be the most direct window into the process of developing topoi. Audiovisual recordings of both the Texas House and Texas Senate hearings have been archived and are accessible through the Texas Legislature Online web site; however, the amount of oral testimony generated by the oversight hearings held on February 25 and 26 is enormous (around 23 hours of video), and transcripts of the hearings are not yet available. In the interest of timeliness, the current study did not undertake to transcribe these interactions. In addition, future researchers might explore the Research Resources compiled for legislators and the public by the Legislative Reference Library of Texas (2021) in advance of the scheduled hearings, as such resources would have served to support legislators’ understanding and interpretation of the event.

Future research might explore the links between topoi and the way stakeholders who have access to mass media frame the issues therein. For instance, a comparison of the text of press releases to published news stories that use, or do not use, the language of the press releases might give insight into how one group’s topoi may be used to shape those of another group. Future researchers might explore the organizations’ own press releases and other public relations efforts, many of which are substantial. ERCOT, for example, maintains a web page on which is linked market notices, payment plan agreements, presentations and other documents, communication with state legislators and with Congress, public information requests, video archives of media briefings, energy emergency alerts, U.S. Department of Energy orders, and Public Utility Commission of Texas orders. Some of this documentation is highly technical in nature; some is aimed at a various lay audience. Further investigation using these techniques may extend research about media framing in public crises (Culley et al., 2010; Giles & Shaw, 2009; Matthes, 2009; Nisbet, Brossard, & Kroepsch, 2003; Pieri, 2019; de Vreese, 2005).

The present study did not undertake to determine the extent to which the public or legislators were able to successfully promote their topoi to news media. Pieri (2019) argues that newspaper coverage or crisis, whether in print or online, still matters. News media still have the ability to frame coverage of crises in ways that create “legacies or dependency paths,” that endure beyond the crisis itself and affect how governments and other institutions plan for and respond to future crises (p. 88). Though Pieri’s work specifically addresses pandemic emergencies, Pieri’s conclusions may be applicable to other types of crisis.

This research focused on addressing the following question: What does the testimony in oversight hearings reveal about how the primary stakeholders of the February 2021 power loss event understood that event? Qualitative content analysis has been effective in distilling stakeholder topoi from a massive amount of expert and nonexpert knowledge acquired from oversight hearing testimony, and this project is but the starting point in an exploration of what public policymakers do with that knowledge. The more that is known, and not just surmised, about stakeholders and how they understand and interpret their technical knowledge, the better we can address further questions about how that knowledge may be communicated throughout the legislative process.

REFERENCES

Agnew, D. (2021, February 19). As Texans endured days in the dark, the state failed to deliver vital emergency information. The Texas Tribune. https://texastribune.org/2021/02/19/texas-emergency-communication-power-outages

Allahyari, M., Pouriyeh, S., Assefi, M., Safaei, S., Trippe, E. D., Gutierrez, J. B., & Kochut, K. (2017). A brief survey of text mining: Classification, clustering, and extraction techniques. arXivLabs. arXiv:1707.02919

Arendt, C., LaFleche, M., & Limperopulos, M. A. (2017). A qualitative meta-analysis of apologia, image repair, and crisis communication: Implications for theory and practice. Public Relations Review, 43(3), 517–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.03.005

Austin, L., Liu, B. F., & Jin, Y. (2012) How audiences seek out crisis information: Exploring the social-mediated crisis communication model. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 40(2), 188–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2012.654498

Benoit, W. L. (1995). Accounts, excuses, and apologies: A theory of image restoration. State University of New York Press.

Bogain, A. (2020). Understanding public constructions of counter-terrorism: An analysis of online comments during the state of emergency in France (2015-2017). Critical Studies on Terrorism, 13(4), 591–615.

Bormann, E. G. (1985). The force of fantasy: Restoring the American dream. Southern Illinois University Press.

Boswell, C. (2009). The political uses of expert knowledge: Immigration policy and social research. Cambridge University Press.

Cambria, E., Poria, S., Gelbukh, A., & Thelwall, M. (2017). Sentiment analysis is a big suitcase. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 32(6), 74–80.

Carlton, J. S., & Jacobson, S. K. (2016) Using expert and non-expert models of climate change to enhance communication. Environmental Communication, 10(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2015.1016544

Chapman, B. (2020). Congressional Committee resources on space policy during the 115th Congress (2017–2018): Providing context and insight into U.S. government space policy. Space Policy 51(2020), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2019.101359

Cheng, M., & Jin, X. (2019). What do Airbnb users care about? An analysis of online review comments. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 58–70.

Christensen, J. (2021). Expert knowledge and policymaking: A multi-disciplinary research agenda. Policy & Politics, 49(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557320X15898190680037

Coles, A. R., & Quintero-Angel, M. (2018) From silence to resilience: prospects and limitations for incorporating non-expert knowledge into hazard management. Environmental Hazards, 17(2), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2017.1382319

Coombs, W. T. (2004). Impact of past crises on current crisis communication: Insights from situational crisis communication theory. The Journal of Business Communication (1973), 41(3), 265–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943604265607

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2002). Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: Initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Management Communication Quarterly, 16(2), 165–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/089331802237233

Culley, M. R., Ogley, O. E., Carton, A. D., & Street, J. C. (2010). Media framing of proposed nuclear reactors: An analysis of print media. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 20(6), 497–512. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.1056

Dragga, S., & Gong, G. (2014). Dangerous neighbors: Erasive rhetoric and communities at risk. Technical Communication, 61(2), 76–94.

Drumheller, K., & Kinsky, E. S. (2021). Rushing to respond: Image reparation and dialectical tension in crisis communication in academia. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 49(4), 406–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2021.1896021

Evans, D. P., & Narasimhan, S. (2020). A narrative analysis of anti-abortion testimony and legislative debate related to Georgia’s fetal “heartbeat” abortion ban. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 28(1), 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2019.1686201

Frith, J. (2017). Big data, technical communication, and the smart city. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 31(2), 168–187.

Frulla, D. E. (2012), Congressional response to public crisis: how corporations can prepare. Journal of Public Affairs, 12(4), 373-380. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1425

Gallagher, J. (2020). Peering into the internet abyss: Using big data audience analysis to understand online comments. Technical Communication Quarterly, 29(2), 155–173.

George, E., & Hovey, A. (2020). Deciphering the trigger warning debate: a qualitative analysis of online comments. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(7), 825–841.

Giles, D., & Shaw, R. L. (2009). The psychology of news influence and the development of media framing analysis. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(4), 375–393.

Graham, S. S., Kim, S. Y., DeVasto, D. M., & Keith, W. (2015). Statistical genre analysis: Toward big data methodologies in technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 24(1), 70–104.

Hancock, K. (2021). Notice of public hearing. Texas Senate.

Kalogeropoulos, A., Negredo, S., Picone, I., & Nielsen, R. K. (2017). Who shares and comments on news?: A cross-national comparative analysis of online and social media participation. Social Media + Society, 3(4).

Karaa, W. B. A., & Dey, N. (2017). Mining multimedia documents. CRC Press.

Lam, C. (2016). Correspondence analysis: A statistical technique ripe for technical and professional communication researchers. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59(3), 299–310.

Lancaster, A. (2018). Identifying risk communication deficiencies: Merging distributed usability, integrated scope, and ethics of care. Technical Communication, 65(3), 247–264.

Lee, S., & Basnyat, I. (2013). From press release to news: Mapping the framing of the 2009 H1N1 A influenza pandemic. Health Communication, 28(2), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2012.658550

Legislative Reference Library of Texas. (2021). Electric power outages and extreme weather events, legislative committee hearings, February 25 and March 4. https://lrl.texas.gov/whatsNew/client/index.cfm/2021/2/23/Electric-Power-Outages-and-Extreme-Weather-Events-Legislative-Committee-Hearings-February-25

Lundin, M., & Öberg, P. (2014). Expert knowledge use and deliberation in local policy making. Policy Sciences, 47(1), 25–49.

Lundgren, R. E., & McMakin, A. H. (2018). Risk communication: A handbook for communicating environmental, safety, and health risks. John Wiley & Sons.

Ma, L., & Zhan, M. (2016). Effects of attributed responsibility and response strategies on organizational reputation: A meta-analysis of situational crisis communication theory research. Journal of Public Relations Research, 28(2), 102–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2016.1166367

Marvel, J. D., & McGrath, R. J. (2016). Congress as manager: Oversight hearings and agency morale. Journal of Public Policy, 36(3), 489–520. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X15000367

Matthes, J. (2009). What’s in a frame? A content analysis of media framing studies in the world’s leading communication journals, 1990–2005. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 86(2), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900908600206

Menchaca, M. (2021, February 14). Texas’ grid operator warns rolling blackouts are possible as winter storm escalates demand for electricity. The Texas Tribune. https://texastribune.org/2021/02/14/texas-rolling-blackouts

Menchaca, M., & Ferman, M. (2021, February 12). Massive winter storm prompts disaster declaration and could stress Texas’ electric grid. The Texas Tribune. https://texastribune.org/2021/02/12/texas-winter-weather

Moore, P. (1992). Intimidation and communication: A case study of the Challenger accident. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 6(4), 403–437.

Moreland-Russell S., Barbero C., Andersen S., Geary N., Dodson E. A., & Brownson, R. C. (2015). Hearing from all sides: How legislative testimony influences state level policy-makers in the United States. International Journal of Health Policy Management, 4, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2015.13

Muddiman, A., & Stroud, N. J. (2017). News values, cognitive biases, and partisan incivility in comment sections. Journal of Communication, 67(4), 586–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12312

Nisbet, M. C., Brossard, D., & Kroepsch, A. (2003). Framing science: The stem cell controversy in an age of press/politics. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 8(2), 36–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X02251047

Paddie, C. (2021). Notice of Public Hearing. Texas House of Representatives.

Pieri, E. (2019). Media framing and the threat of global pandemics: The ebola crisis in UK media and policy response. Sociological Research Online, 24(1), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780418811966

Price, A. (2021, February 22). Texas politicians saw electricity deregulation as a better future. Years later, millions lost power. USA Today. https://usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2021/02/22/texas-power-grid-outages-did-ken-lays-deregulation-set-calamity/4540029001/

Public Utility Commission of Texas. (2021, February 14). Cold-driven demand makes electricity conservation necessary [Press release]. https://puc.texas.gov/agency/resources/pubs/news/2021/PUCTX-REL-COLD21-021421-CONSERVE-FIN.pdf

Riffe, D., Lacy, S., Watson, B. R., & Fico, F. (2019). Analyzing media messages: Using quantitative content analysis in research. Routledge.

Ross, D. G. (2013). Common topics and commonplaces of environmental rhetoric. Written Communication, 30(1), 91–131.

Rude, C. D. (1997). Environmental policy making and the report genre. Technical Communication Quarterly, 6(1), 77–90.

Rude, C. D. (2004). Toward an expanded concept of rhetorical delivery: The uses of reports in public policy debates. Technical Communication Quarterly, 13(1), 271–288. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427625tcq1303_3

Texas Senate. (2021). Senate Committee on Business & Commerce Interim Report to the 87th Legislature. https://senate.texas.gov/cmte.php?c=510

Shaffer, R. (2017). Cognitive load and issue engagement in congressional discourse. Cognitive Systems Research, 44, 89-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsys.2017.03.006

Simmons, W. M., & Grabill, J. T. (2007). Toward a civic rhetoric for technologically and scientifically complex places: Invention, performance, and participation. College Composition and Communication, 58(3), 419–448.

Taylor, C. A., Al-Hiyari, R., Lee, S. J., Priebe A., Guerrero L. W., & Bales, A. (2016). Beliefs and ideologies linked with approval of corporal punishment: A content analysis of online comments. Health Education Research, 31(4), 563–575. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyw029

The Texas Legislative Council. (2018) The legislative process in Texas. https://tlc.texas.gov/docs/legref/legislativeprocess.pdf

United States Energy Information Administration (2021, February 19). Extreme winter weather is disrupting energy supply and demand, particularly in Texas. Today in Energy. https://lrl.texas.gov/whatsNew/client/index.cfm/2021/2/23/Electric-Power-Outages-and-Extreme-Weather-Events-Legislative-Committee-Hearings-February-25.

Vaismoradi, M., & Snelgrove, S. (2019, September). Theme in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(3).

de Vreese, C. H. (2005). News framing: Theory and typology. Information Design Journal + Document Design, 13(1), 51–62.

Wendling, C., Radisch, J., & Jacobzone, S. (2013). The use of social media in risk and crisis communication. OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, 24. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k3v01fskp9s-en

Williams, M. F. (2009). Understanding public policy development as a technological process. Journal of Business & Technical Communication, 23(4), pp. 448–462. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F1050651909338809

Winsor, D. A. (1988). Communication failures contributing to the Challenger accident: An example for technical communicators. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 31(3), 101–107.

Yanow, D. (2000). Conducting interpretive policy analysis. SAGE Publications.

Youngblood, S. A. (2012). Balancing the rhetorical tension between right to know and security in risk communication: Ambiguity and avoidance. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 26(1), 35–64.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Rachel Martin Harlow is an associate professor of communication at The University of Texas Permian Basin in Odessa, Texas. Her work in industry and the academy has led her to focus her research on technical communication in the public sphere, particularly on reports and other public documents produced for complex audiences. She may be reached at harlow_r@utpb.edu.

[1] In Texas, most bills are submitted to either the House or the Senate. A bill that survives committee review and floor deliberation in the original chamber to which it was submitted is referred to the other chamber, where it undergoes the same process of committee review and, if the committee regards it favorably, to floor deliberation. If the bill survives that, it is returned to the originating chamber, which reviews the second chamber’s amendments, if any. If the originating chamber concurs with the amendments, the bill is approved by both chambers and sent to the governor. Some bills, however, are cosponsored by members of both chambers. Cosponsored bills have identical text but are submitted to both legislative chambers concurrently and are treated as separate bills (Texas Legislative Council, 2018).

[2] The state word family also included references to utterances and to conditions. The weighted percentage value accounts for this overlap.