doi: https://doi.org/10.55177/tc485629

By Gabriel Lorenzo Aguilar

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Humanitarian audiences are inaccessible to our traditional methods of research. Audiences like migrants often rely on technical communication to find humanitarian aid; however, there are few methodologies that can help us improve materials for them. This project explores world-traveling to demonstrate how the methods of other fields can help us take a proactive approach in critiquing and improving the technical communication from humanitarian operations.

Methods: World-traveling is the practice of seeing through another’s eyes to anticipate what they may need (Lugones, 2003). It calls us to travel from our privileged “worlds,” spaces we inhabit as scholars, into the worlds of vulnerable populations. The practice helps researchers understand the worlds of marginalized populations and help them. I world-travel to migrant women in an archive to improve a map that migrants use to find water in the Arizona desert.

Results: World-traveling allowed me to anticipate problems. I found that migrant women are at a much higher risk of death by exposure than men and that the current maps of water hide this risk. I redesigned the map with the intent to lessen the risk of death by exposure for migrant women. The redesign made it clear that women are at risk of a certain harm while also taking steps to humanize the women displayed on the map.

Conclusion: World-traveling allowed me to show migrant women the increased risk of death by exposure through a redesigned map. The result is more useful and humane technical communication.

KEYWORDS: Humanitarian Technical Communication, World-Traveling, Transnational Feminism, Undocumented Migrants

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Technical communicators should recognize humanitarian organizations as important sites of our work.

- This study introduces world-traveling as a praxis.

- The study also brings awareness to migrants’ needs on the U.S. border and beyond.

- The results of the study provide strategies for redesigning maps for migrants at borders.

“Thus, the example always needs to be interpreted; it never stands in our face, showing us anything without intervention.”

-Maria Lugones in Pilgrimages/Peregrinajes (p. 27).

INTRODUCTION

It is difficult to study technical communication from humanitarian operations. The audiences often consist of the most vulnerable in the world (migrants, refugees, and asylees), populations that don’t stay in one place for long. The humanitarian organizations that help these populations are wary of researchers—and rightfully so. To distribute humanitarian aid requires trust in the community; the intrusiveness of primary research can disrupt community trust between people and humanitarian operations while the ephemerality of people in dire need makes secondary analyses an inconsistent method. In short, if our field wants to fully engage with improving the technical communication at humanitarian operations, we need to find other ways to study them. Technical and professional communication (TPC) needs to look beyond our conventional methods in primary and secondary research to critique and improve the technical communication that comes from humanitarian contexts.

But how do we know if a problem exists in the first place? Humanitarian operations often don’t wait for a communication problem before they act (Mays, Walton, & Savino, 2013) nor do they rely on what Ramler (2021) calls “postadoption feedback” (p. 346). The idea is that marginalized populations often can’t provide user feedback on a technology in the same way that more conventional audiences like students or consumers might. Anticipation of problems from keen technical communicators is key in certain contexts. In Ramler (2021), she explains that “emphatic reach,” an ethical vision that “enables writing for future audiences,” is a method she uses through a queer framework to anticipate the problems that queer audiences might face when using social media platforms (p. 347). It is a writing for the future with recognition that waiting for a postadoption by marginalized audience is ineffective in certain circumstances. Ramler (2021) understands that there are certain contexts in which we must be proactive. I believe humanitarian contexts meet such criteria. To answer the question at the beginning of this paragraph: many times we don’t know if a problem exists but we can enact a proactive, prepared and response approach to get ahead of potential problems in humanitarian operations (Mays et al., 2013; Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship, 2003; Walton, Mays, & Haselkorn, 2016).

I want to demonstrate how I recognized and improved upon a potential technical communication problem at a humanitarian operation, Humane Borders (HB). HB distributes water to migrants via 80 water stations throughout the desert. Not only does HB distribute water, but they also create materials such as maps that can help migrants find water. However, these maps could be problematic because they flatten the diverse migrant population into singular, fixed points of data. Now, in more conventional situations (like in the classroom, industry, or government), researchers could use traditional methods to improve materials based on some type of feedback from what we would traditionally call a user: we could set up surveys, interviews, user experience workshops, focus groups. However, as I have come to experience, when we need to improve the technical communication for an audience as vulnerable as migrants, there are often few avenues to collect data. I have been told “no” many times by humanitarian organizations when I ask if I can study the technical communication sent out to migrants, refugees, and asylees. The responses I receive are mostly on the lines of “migrants are too vulnerable to give informed consent” and “refugees are in a situation where it can come across as unethical to present yourself as a researcher as opposed to a translator or volunteer.” I looked outside TPC to see how other fields circumvented problems of methodology such as the ones I came across. World-traveling, and its situatedness in transnational feminism, offered one solution.

This project adopts transnational feminist Maria Lugones’ (2003) theory of world-traveling to redesign a map of water stations for migrant women crossing the Arizona desert. World-traveling specifically, and transnational feminism in general, allows me as a researcher to gather data from an audience of migrant women who cannot be researched through interviews, ethnography, or other direct forms of study because many are deceased or in a vulnerable position where researchers are not allowed to directly engage with them. The aim of this adoption is to demonstrate to TPC the value of adding world-traveling to our catalogue of appropriate research methodologies; doing so, justly, can help us create and critique technical communication for audiences who otherwise would remain inaccessible.

I inhabit both a privileged and a marginalized world. I am a person of color from a very marginalized undocumented community, a Chicano from the barrios of the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas—one of the poorest and least educated places in the country. I have world-traveled to survive; it is one of the reasons I wrote this article. However, I am also an inhabitant of a privileged world. I am a scholar and researcher, like Lugones (2003) and so many other people of color in academia, while also an inhabitant of a marginalized world. I have been trained in Western institutions. I write in and for Western audiences. My world-traveling will look different than your world-traveling, and there is much room for addition and critique. In fact, Lugones (2003) encourages it. There is room to build upon world-traveling as, at face value, it can overlook critical intersections of identity, particularly when it comes to race. The redesigned maps I made in this project are not perfect; my own practice of world-traveling is not perfect. There will be a heuristic at the end of this article that can help researchers understand how to world-travel that includes guiding questions that can help researchers locate themselves in their own worlds. While this heuristic is ever evolving and open for revisions, I hope readers can understand the value of the praxis and look to build upon an addition that could very much have our field help in humanitarian contexts.

TPC and WORLD-TRAVELING:

SIMILAR GOALS, DIFFERENT METHODS

As more scholars of color from marginalized communities join academic conversations in technical communication, critical questions arise about how to include marginalized populations in our studies. Scholars such as Godwin Agboka, Natasha Jones, Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq, Emily January Petersen, Rebecca Walton, Jared Colton, and Steve Holmes among many others investigated how to “ensure that groups and individuals receive equal opportunities and are not marginalized and disenfranchised” (Jones, 2016, p. 472). Social justice as an approach in technical writing has led us to new findings in the field such as the recognition that marginalized communities inform technical communicators (Agboka, 2013) and that this information is crucial in making communication more accessible and less oppressive to the most marginalized of communities (Colton & Holmes, 2018). Thus, we arrived at a good working definition of social justice technical communication:

Technical communication [that] investigates how communication broadly defined can amplify the agency of oppressed people—those who are materially, socially, politically, and/or economically under-resourced. Key to this definition is a collaborative, respectful approach that moves past description and exploration of social justice issues to taking action to redress inequities (Walton & Jones, 2018 qtd in Jones, 2016 p. 347).

There are key concepts to take away from this definition. The social justice turn pushes researchers to not only think about ways to amplify agency but also to act in socially just ways. There is a call for theory and praxis that has been demonstrated by many during this social justice turn. One of the key examples comes from Agboka (2013) where he theorizes the social justice potential of localization while applying this theory to a case of a marginalized group (Ghanaians) being harmed by mistranslated sexuopharmaceuticals. The result was an advocacy for considering social and cultural factors when translating to another language. What Agboka (2013) demonstrated, and what many in the social justice turn demonstrate, is that we can be facilitators of agency for the marginalized. We do not speak for them but instead find avenues that amplify their agency to help reduce risks associated with marginalization.

Like much of the social justice work in TPC, world-traveling, and its location in transnational feminism, is invested in amplifying the agency of marginalized communities. Broadly, transnational feminism unflattens people of color’s experience in data, an unflattening that those in TPC might describe as an amplification of agency. For example, Mohanty (2003) finds that Western feminist scholars objectify displaced peoples by haphazardly engaging in “Methodological Universalisms” or “Women’s Oppression as a Global Phenomenon” (p. 33). Researchers can portray the harmful experiences of displaced people, and women of color in particular, to be universal. The solutions to those problems are then also portrayed as universal. Lugones (2003) spends some time foregrounding world-traveling in her experiences as a woman of color in academia. Many of the white men in her field saw the contributions of her colleagues of color as impoverished and in a state of sameness: the work of one woman of color is the work of all women of color, essentially.

Both technical communication and world-traveling argue against the flattening of people, albeit they take different approaches for different reasons. World-traveling theorizes against flattening through experienced-based, as opposed to empirically based, research. In this, it echoes social justice and feminist technical communication that have included experiences as a valid form of data collection (Petersen & Walton, 2018). However, experienced-based research in TPC is often conducted by scholars who have access to the audiences they are researching and are done in situations in the classroom, workplace, or industry. For example, while authors like Agboka (2013) and Jones (2016) use experience-based research to advocate for more inclusion of marginalized participants in TPC, some of their findings depend on the ability to reach their audience in conventional ways like interview, ethnography, case study, secondary research, and other methodologies in which a researcher can collect data directly from an audience. Similarly, Cui (2019) applies experienced-based feminist theory, Ratcliffe’s (2005) rhetorical listening, to improve students’ class-cultural communication and multimodal experiences in the classroom—again focusing on a traditionally researchable audience (the composition student) in an accessible location (the classroom). In contrast, world-traveling allows researchers to collect data from audiences that can’t be reached through traditional methodologies.

WORLD-TRAVELING TO INDIRECTLY COLLECT DATa

Before this section explains world-traveling, I’d like to highlight some concerns scholars have over world-traveling and its privileging of whiteness. Lugones’ (2003) interpretation of world-traveling fails to critically engage with race; however, because her endeavor is open-ended, scholars can critically include race into the conversation. Ortega (2016) promotes the idea of a “critical world-traveling” which takes into account the problem of whiteness and privilege that Lugones (2003) overlooked (p. 141). Essentially, many have critiqued world-traveling for its failure to recognize how the inherent privileges of certain people in communities of color allow them to world-travel more so than others (Lugones’ (2003) claim that one must be playful when world-traveling can come across as haphazard. We tend not to think of playfulness when researching the oppression of groups of people). Whiteness, for example, promotes the world-traveling of white-passing, or lighter skinned Latinxs while their dark-skinned counterparts are more restricted. Blackness can be erased when we world-travel as the gatekeepers of the dominant worlds can filter which world travelers they find appealing.

Because world-traveling is a new methodology to our field, this particular project will focus mostly on Lugones’ (2003) initial understanding of world-traveling and will not fully engage with critical world-traveling. This is not to say that I was not wary of the problematics of world-traveling (there are some redesign features where I take race and whiteness into account); however, I wanted to showcase the pragmatics of world-traveling to the field and then allow for open-ended conversation on how to improve our engagement of the methodology. Future projects will better critique world-traveling and its application in TPC.

Lugones and World-Traveling

World-traveling is the practice of visiting other people’s “worlds,” a figurative or physical place where people, alive or dead, inhabit. Lugones (2003) purposefully leaves “world” broadly defined and states that “I do not want the fixity of a definition at this point, because I think the term is suggestive and I do not want to close the suggestiveness of it too soon” (p. 83). But it’s important to know that we, as people with multiple identities, all inhabit worlds. Some of our worlds are intimidating to others, especially if we are privileged in our world; some people are content in staying in their own worlds and never travel to others; and some people must travel to other people’s worlds for survival (Lugones, 2003). In essence, the act of traveling can come from a privileged space or a space of survival depending on the other worlds we inhabit and the identities we possess. A white middle-class man scholar may be content to stay in the world that welcomes white middle-class men scholars; this person may never travel to the worlds of, let’s say, the brown custodial staff that cleans the physical places of the privileged world, of his office space; this person may never travel to the worlds of his working-class students where there are invisible tensions that pose the privileged person as a gate keeper to privileged worlds. Both worlds, whether it is physical as in the office or not-so-physical as in the tension between the scholar and student, must be visited by the less privileged for survival. The brown custodial staff must enter the world of the scholar in order to survive: there was an interview process, there is a protocol for his cleaning, there is an understanding of what’s important on the scholar’s desk so as to be extra careful while cleaning. The working-class student must enter the world of the scholar to survive: there is a power dynamic in which the student needs to meet the scholar’s expectations to pass the course despite the situation that makes it incredibly difficult for working class students to do so.

According to the text, all people can world-travel regardless of their privilege (or lack thereof),[1] but certain people can travel in harmful ways. Sometimes traveling is willful and at other times not (Lugones, 2003, p. 90). I interpret that willful traveling is usually done by those who are privileged in their worlds—they can choose whether or not they travel. Lugones (2003) warns the inhabitants of privilege worlds about their dangers of traveling; dangers not so much in that their traveling can harm their own sense of security in their own world, but danger in that traveling from a privileged world can lend a privileged person an imperialist drive. There is a risk that an “agonistic traveler” will visit the world of a marginalized person with a conquest in mind (Lugones, 2003, p. 87): to assimilate the other world to the standards of the privileged, to enact what Mohanty (2003) would call a Methodological Universalism, to consider the experiences of the marginalized in objective ways, to flatten. Therefore, it takes incredible reflexivity and what Lugones (2003) calls “playfulness” for a person from power to travel to the world of marginalized people (p. 87). That privileged person must visit with a playful attitude, an approach that welcomes uncertainty with an “openness to surprise” and a “metaphysical attitude that does not expect the [marginalized] world to be neatly packaged” (Lugones, 2003, pp. 88–89).[2] In other words, to return to my epigraph, being playful is a necessary skill of the privileged traveler because it gives us the attitude to understand that these marginalized worlds are often distorted and manipulated by dominant powers—“it never stands in our face, showing us anything without intervention” (Lugones, 2003, p. 27). Further, reflexivity and playfulness allow us to see past the objectivity that is often presented by Western (re)production of marginalized worlds; we should be open to the uncertainty and surprise that people in marginalized worlds are harmed in ways other than those depicted by Western worlds.

To world-travel from worlds of privilege to marginalized worlds is to collect data in untraditional ways.[3] The term “playfulness” is used consistently in Lugones (2003) as a characteristic of being open to surprise and to be unconquering as we visit other worlds. Lugones (2003) clarifies that playfulness here is not about competition or winning; rather, it’s about accepting that our perspectives of marginalized worlds are often shaped by dominant worlds to make the marginalized seem lesser and other. Lugones’ (2003) world-traveling gathers information in valuable, yet indirect, ways to understand the needs of marginalized peoples. As she puts it, “we inhabit ‘worlds’ and travel across them and keep all the memories” (Lugones, 2003, p. 90). Memories are the keepsakes one gathers when world-traveling: a playful traveler experiences the norms and harms of those that inhabit a certain world and holds them as memories as that traveler visits other worlds. I interpret Lugones’ (2003) keeping of memories as a form of data collection in which she gathers information from marginalized and dominant worlds to make theories about the relationship between and among the worlds she visits. To demonstrate her data collection, Lugones (2003) sets up two worlds and their colonial relationship, the world of the white and privileged (a world of power) and the world of women of color in the U.S. (the marginalized). Lugones (2003) acknowledges that she inhabits and travels between both of these worlds.[4] She can see that those who inhabit the white and privileged world, people who she specifically addresses as “White/Anglo” (Lugones, 2003, p. 79), do not world travel to the worlds of the marginalized or, if they do, travel in imperialistic ways. They fail to identify with those who they find subordinate; they fail to engage in a playful exploration and ignore the marginalized unless they need the experiences of the marginalized to advance their careers. However, as a person who also inhabits both the privilege and marginalized worlds, Lugones (2003) does travel between them. She investigates the ways the privileged worlds contribute to the marginalization of certain people. For example, Lugones (2003) studies how White/Anglo people ignore women of color and reports on the harm felt by those in marginalized worlds she inhabits. These keeping of memories, I argue, are a form of data collection not based on empirical methods but through the transnational feminist method of world-traveling. Lugones (2003) engaged in a playful attitude to explore both worlds, made the effort to travel back to the marginalized after inhabiting the privileged world, and traveled once again to the privileged world to publish her findings (all steps in her collection and publication of data).

Lugones (2003) engages with practices of world-traveling to show the reflexivity it takes for those in privileged worlds to understand the power dynamics when we stay in or travel from our own world and when we decide who gets to enter our world or if others get a say if we visit theirs. All of us inhabit our worlds and many of us world-travel. Because of our involvement in academia (be it as graduate students, junior faculty, full-time professors, or administrative and other staff), we do inhabit a powerful world, a privileged world. Because many of our investments as scholars are to help marginalized people (and, in turn, marginalized worlds), with an awareness of what world-traveling overlooks in terms of race (Ortega, 2016), we must practice the same reflexivity that Lugones (2003) demonstrates in that we are coming from worlds of power and can travel to marginalized worlds through playful and helpful ways.

World-traveling can help us research inaccessible audiences. There can be, and most certainly is, a study that collects data on how people of color are marginalized and harmed by Western researchers. However, even in the most comprehensive studies, there are certain people who cannot participate through traditional methodologies because of their vulnerability. Lugones (2003) not only collects data through world-traveling to people that can be reached by traditional methods, she also world-travels to people who are not alive. For example, she world-travels to the world of her deceased mother to better understand why their relationship was strenuous when she was alive. Through world-traveling, Lugones (2003) discovers that her mother was a plurality of identities; that at once, her mother inhabited a marginalized world that made her subordinate to the worlds of the powerful while also performing a stereotype expected by the worlds of the dominant. World-traveling helped Lugones (2003), through a playful attitude, understand that her mother was at times performing for the expectations of agonistic travelers—a performance that often led to conflict between them as her mother often critiqued Lugones’ (2003) for her lesbianism and Lugones (2003) in turn “abused” her mother back (p. 82); the abuse mentioned in the text means that Lugones arrogantly perceived her mother to be a servant without agency to dominant worlds. This insight provided a conclusion for Lugones (2003). Her mother, like so many other women of color, was held to an unfair standard and was performing that standard for survival. Lugones (2003) would not have realized that her mother was a victim of the privileged worlds, but world-traveling helped her understand. This is valuable data that Lugones (2003) takes with her to the powerful world as scholarship, not for the advancement of her career, but as a contribution in the hopes of helping other scholars avoid imperialist world-traveling.

The Limitations and Potential Harms of World-Traveling

While Lugones (2003) may have given a name to the practice of world-traveling, she did not invent it. World-traveling has existed before, and the harm of imperialist and colonial world-traveling has been well documented. Some may have seen the harms as cultural appropriation, theft of a marginalized population’s intellectual property or intellectual resources, or even as racial tourism—visiting the headspaces of the marginalized as a tourist, to gawk at oppression without an engagement to resolve oppression and only to tell others in more privileged worlds how bad it is over there (Vats, 2014). It is true that Lugones (2003), despite her warning of imperialist, agonistic, world-traveling leaves too much room for others to world-travel in harmful ways. However, I argue that because she has given it a name and an open-ended endeavor to improve it, our field can better understand the limitations and harms of world-traveling and ensure we are helping much more than we are harming.

One limitation is to remember that world-traveling is a praxis in a field that values material contribution. A recurring grievance of transnational feminism and world-traveling is the academic acceptance that describing the situations of the marginalized back to privileged worlds is enough (Lugones, 2003; Mohanty, 2003). Thus, if we want to world-travel, we must do so with an intervention that improves the situation of the marginalized. In this project, for example, my world-traveling led me to redesigning a map for migrant women.

Another limitation is that the praxis of world-traveling can, even unintentionally, be more for those in privilege worlds and not for those residing in the margins. Lugones (2003) reports that those who world-travel can attempt to transform a situation in the worlds of the marginalized only to leave it when they return to their privilege world. Transnational feminism has well documented this phenomenon (Mohanty, 2003). In today’s terms we may call it virtue signaling, a half-hearted attempt to display our awareness of an injustice without a full engagement of the situation. In academia, the temptation for many is to publish about their world-traveling without ever returning to the site—as soon as the scholar gets another line on their CV, it’s on to the next project. My upcoming intervention is one I have been working on for years in tandem with a humanitarian organization. I plan to donate my research and redesigns to the organization while also improving my praxis of world-traveling in future redesigns and interventions.

The final limitation I’d like to note is that world-traveling is a still a way to work with what we have. Researchers need to have information about a demographic in order to world-travel. And that information influences how a researcher world-travels and the extent of the intervention. For example, I first studied an archive of deceased migrants for months before feeling comfortable to world-travel to a specific demographic. That archive gave me specific information about a migrant’s sex, age, cause of death, and name. Other information such as country of origin, sexuality, and race were not catalogued. Thus, my world-traveling focused on the available information to listen to the needs of a specific demographic. I found, out of many, that migrant women were not made aware of the risks of exposure.

There is great risk in harming marginalized worlds in world-traveling. Haphazard scholars have done harm before and after Lugones (2003) gave name to the praxis. However, because we have a name, an ethics, and the room to critique and improve world-traveling, there is much we can do as practitioners and researchers in TPC to genuinely improve the worlds of the marginalized. We must keep in mind the limitations to do so. World-traveling requires us to intervene in some way while ensuring our interventions are for the marginalized and not for our own personal gain. Our interventions must also be ever-evolving, always attentive to possible improvements or changes. Finally, our world-traveling is limited to working with what we have, the information available. With these limitations in mind, I’d like to demonstrate my world-traveling.

CASE STUDY: THE MIGRANT WARNING POSTER

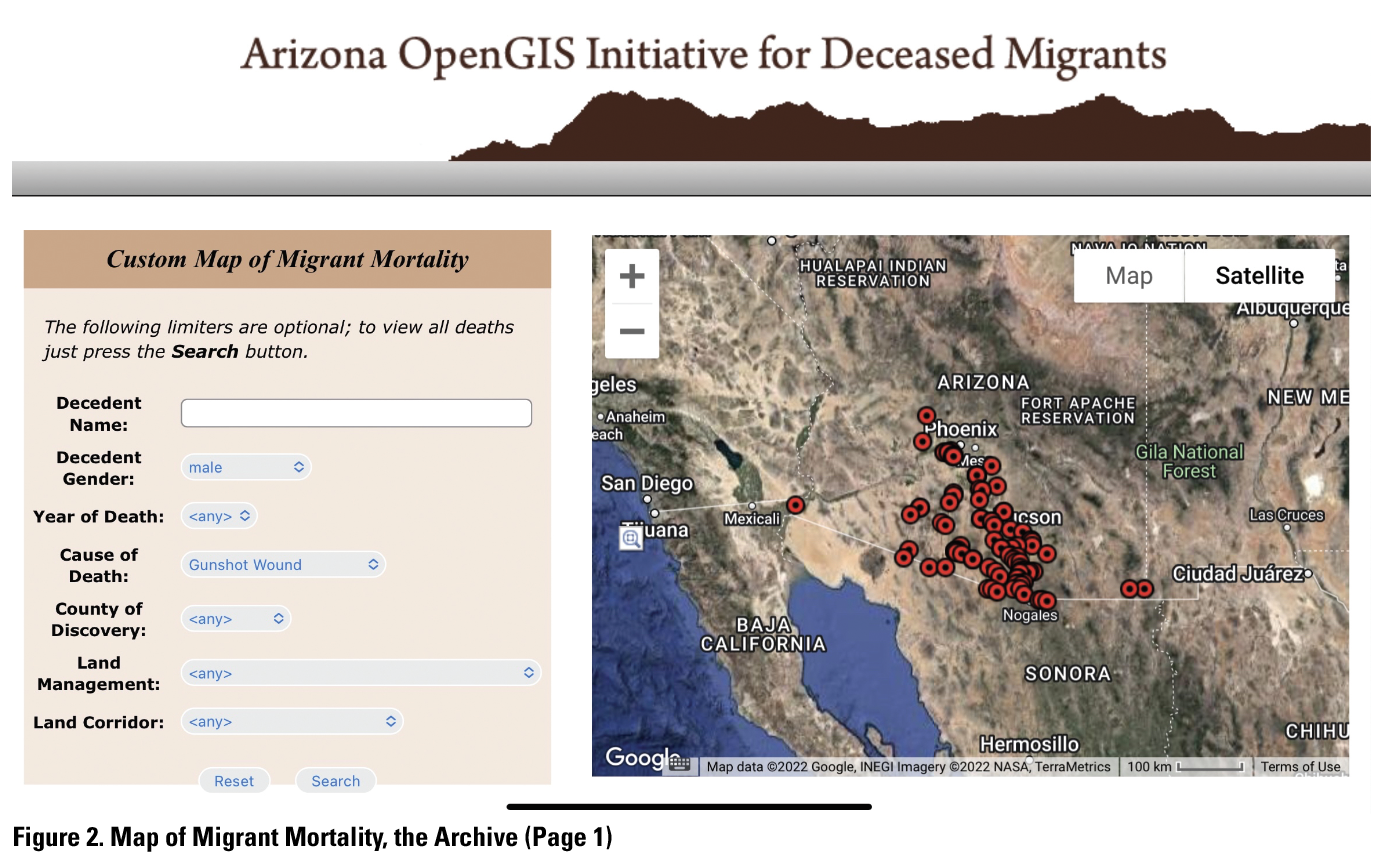

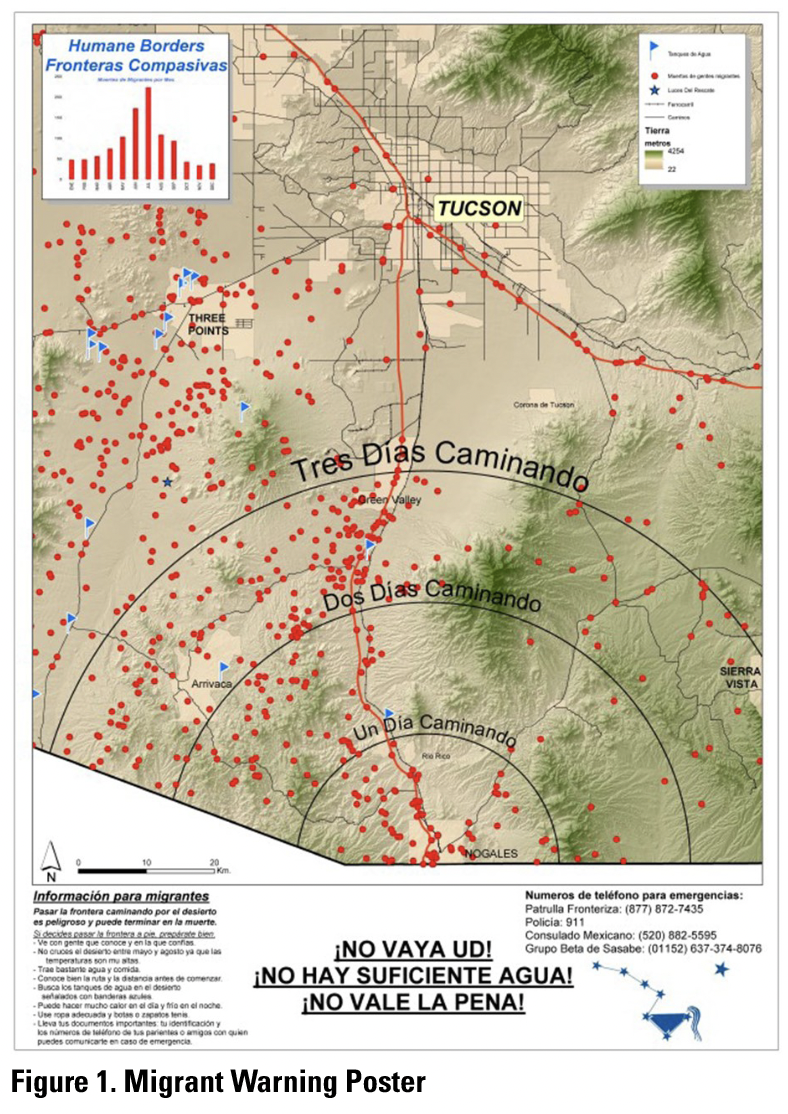

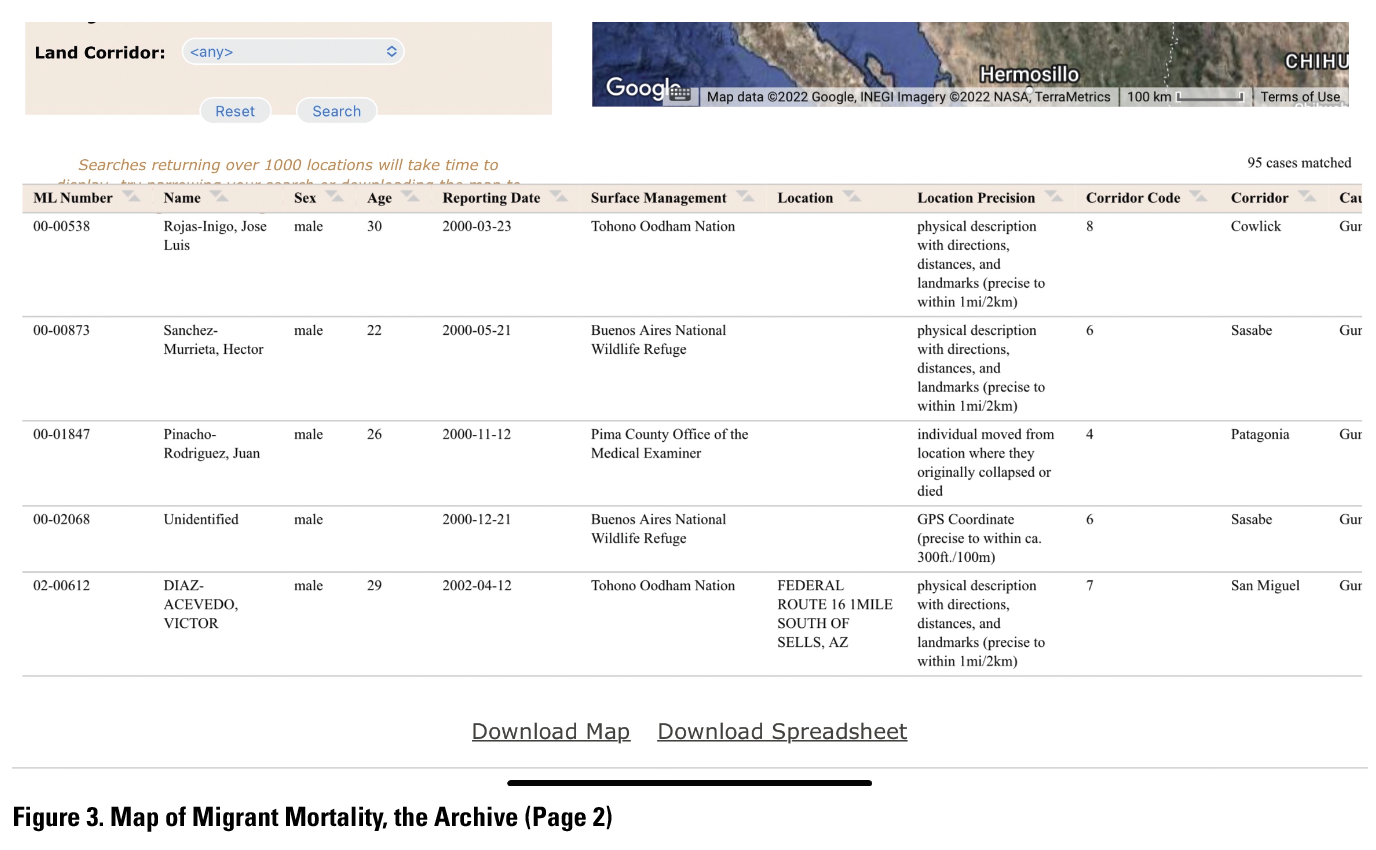

This section explains my redesign of Humane Border’s “Nogales Migrant Warning Poster” (Figure 1) to demonstrate how the field can world-travel to create materials for the needs of undocumented migrants—an audience that is difficult to traditionally research. The Migrant Warning Poster is a map that is printed and distributed to migrants. Humane Borders (HB) is a humanitarian organization based in Tucson, Arizona that distributes water to migrants in dire need via 80 water stations strategically placed all throughout the desert. Water stations are located based on the number of deceased migrants that Humane Borders has tracked over the last 21 years. The data is publicly available through Humane Border’s database, the Map of Migrant Mortality, in which the public and researchers alike can search from over 3,000 deceased migrants with filters such as name, gender, year of death, cause of death, county of discovery, land management, and land corridor. The Map of Migrant Mortality (shown in Figures 2 and 3) is weekly updated and is the primary reference as to where Humane Borders places their water stations. The Map of Migrant Mortality feeds the data found on the Migrant Warning Poster. Technical communicators transfer the data from the Map of Migrant Mortality to the Migrant Warning Poster to show potential migrants the location of both water stations and deceased migrants along with other information about traveling through the desert.

Usability and Map Making

While it is almost impossible to gather user experience directly from populations in humanitarian contexts, this project directly looks at Humane Borders’ map through a rhetorical lens that rejects a flattened, objective depiction of people in the hopes to promote usability. I take Welhausen’s (2015) definition of rhetorical map making along with Dragga & Voss (2001, 2003) and Propen (2007) to investigate how to promote humanity in my redesign. More is to be described in the case study, but Welhausen (2015) argues that what makes maps rhetorical is the omission of certain key geographical, bodily, and/or political information. Dragga and Voss (2001, 2003) find that maps can often omit the humanity of people in data, making it a rhetorical endeavor for technical communicators to add that humanity back through critique. Finally, Propen (2007) explains that usability goes beyond the individual user and in fact extends into the user’s environment.

While it is almost impossible to gather user experience directly from populations in humanitarian contexts, this project directly looks at Humane Borders’ map through a rhetorical lens that rejects a flattened, objective depiction of people in the hopes to promote usability. I take Welhausen’s (2015) definition of rhetorical map making along with Dragga & Voss (2001, 2003) and Propen (2007) to investigate how to promote humanity in my redesign. More is to be described in the case study, but Welhausen (2015) argues that what makes maps rhetorical is the omission of certain key geographical, bodily, and/or political information. Dragga and Voss (2001, 2003) find that maps can often omit the humanity of people in data, making it a rhetorical endeavor for technical communicators to add that humanity back through critique. Finally, Propen (2007) explains that usability goes beyond the individual user and in fact extends into the user’s environment.

While well intentioned, Humane Border’s map is a testament to Western positivism, what Lugones (2003) would call an “agonistic” perspective (p. 90). I find that the depiction of deceased migrants as rigid, fixed red dots come across as harmful to the migrants displayed on the map. Rhetoric and TPC have thoroughly shown that there is a stigma in presenting data: practitioners and audiences alike tend to turn away from data presented as rhetorical and complicated (Atherton, 2021; Dragga & Voss, 2001, 2003; Propen, 2007; Welhausen, 2015). It’s easier to digest an “objective” dataset and to hold numbers as the authority-without-bias. However, real rhetorical work is at play between those who create and those who read materials created from datasets. Objective data creates an illusion of an objective situation and, thus, an objective response (Bacha, 2018; Haraway, 1988; Kimball, 2006; Welhausen, 2015). A response here might be “place more water where we find more red dots”—a solution that might seem intuitive until we find that those red dots are diverse and complex. A rhetorical approach to this map might find that there needs to be better depictions of the people that represent those red dots (Dragga & Voss, 2001, 2003). And with better depictions come more descriptive problems and more appropriate solutions (Propen, 2007). The red dot cannot stand for everything a person is or needs.

I approached this map with both a TPC and world-traveling lens and found that those rigid, fixed red dots hide a reality that needs to be addressed. The Migrant Warning Poster does not show that women are at an elevated risk of death by exposure when compared to men. According to my research on the Map of Migrant Mortality (the archive that feeds the warning poster), migrant women[5] are much more likely[6] than migrant men to die of exposure (dehydration, hypothermia, and heat-related deaths) across all corridors[7] of Humane Borders’ water distribution. However, the current warning poster does not show that women are at more risk of death by exposure than men. I believe that a world-traveling lens towards the migrant women in the archive in a redesign can help make this more evident for migrant women. The redesign could show migrant women that they are more at risk of death by exposure, showcase how other factors like age and travel trajectory effect the likelihood of death by exposure, and also replace the rigidness of red dots to something that is more humane to the lives lost in the desert. This redesigned map could be printed and distributed along with the original map to ensure migrant women are able to see it.

A map can reproduce harm to people if translated through an “agonistic” perspective (Lugones, 2003, p. 94). The rigidity of red dots representing lives (-lost) in the Migrant Warning Poster does not exist in a vacuum. There was a careful design plan that translated the lives (-lost) found in the Map of Migrant Mortality to the Migrant Warning Poster. The dataset in this case does have information about deceased migrants that is not found on the Migrant Warning Poster: information such as name, gender, location found, cause of death, and year of death are omitted from the warning poster. The exclusion of this information is rhetorical because “the purpose of creating any map is to arrange select geographic content into an abstracted visual representation that emphasizes certain features and minimizes others (inclusion and exclusion) in constructing new spatial relationships that advance a particular understanding and interpretation of that space” (Welhausen, 2015, p. 268). In the case of the Migrant Warning Poster, the rhetorical decision was to exclude the name, gender, and location and time of death to advance the understanding that this information is not needed for a migrant to find water. What is supposedly needed for migrants is the approximate location of deceased migrants alongside blue markers of water. However, as I’ve argued through a world-traveling lens, not including this information hides that women are at an elevated risk of death by exposure than men and can reduce migrants’ lives to a singular entry of data—both of which perpetuate violence by not warning a certain demographic of an increased risk and reducing the lives of deceased migrants into reproducible red dots.

The practice of world-traveling may reduce the harm of translating data from the Map of Migrant Mortality to the Migrant Warning Poster. The people who created the current Migrant Warning Poster approached deceased migrants in an agonistic way. The translation from archive to map reduced a diverse population to red dots. World-traveling to the people in the archive can help reduce the harm in that translation by playfully exploring the worlds of those in the archive, a practice that can allow TPC to create materials for inaccessible audiences.

I approached the original map with a wariness of objectivity. This wariness of what was presented led me to dig deeper into the demographics not shown in the original warning poster. There were many hidden crises in the data. Men are much more numerous than women in terms of bodies found (the ratio is almost 4:1); men are more likely to die of gunshot wounds or motor vehicle accidents while women are more likely to die of drowning and, in the focus of my redesign, by exposure. The repercussions of this redesign should not hold women’s issues as the limit of world-traveling. If my focus were on redesigning this map with men in mind, this would still be a transnational feminist project as both women and men migrants are victims of displacement by the dominant Western world. Nonetheless, this project is focused on creating a new Migrant Warning Poster for women that shows migrant women the increased risk of death by exposure and hopefully provide information that can lessen that risk.

My World-Traveling to Migrant Women

My World-Traveling to Migrant Women

There was no usability testing when it comes to the Migrant Warning Posters. Unlike many other audiences in TPC, migrants are especially vulnerable and the organizations that help migrants are wary of academics. I’ve been respectfully told “no” many times by humanitarian organizations; however, I believe technical communication to be important work even for the most vulnerable of populations. I sat with the Nogales Warning Poster for years, sketching ideas as to how I can improve this map in valuable ways without the traditional feedback of an audience. The more I sat with the map, and the more I continued looking for other ways to collect data, the clearer transnational feminism became as one way to make a contribution. Rhetorically, this map can clearly be improved. We understand that the key to improving this map lies in the relationship between the involved rhetorical parties such as migrants, researchers, the public, and volunteers. However, the outlets to collect data on the migrants that use this map are just not there. This is an inaccessible audience.

The nameless, genderless red dots on the Migrant Warning Poster made me uneasy. I was uncomfortable with the idea that this was all that could be presented in a document crucial to the survivability of migrants crossing the Arizona desert. The objectivity in the Migrant Warning Poster presents lives(-lost) as a universal problem with a universal solution (Dragga & Voss, 2001, 2003). There are migrants dying here, so here we place water. In a practice of world-traveling, I explored the archive with the openness of surprise. I tried to imagine the diversity not shown by these red dots. What are their names? What are their genders? What are their nationalities and races? What are their ages? How are they harmed? How can I/we help alleviate some of that harm? I traced the data on the warning poster to its dataset, the Map of Migrant Mortality. This dataset is diverse. You can search the names, genders, ages, locations of death, causes of death, and years of death from a set of over 3,700 deceased migrants. It is evident that there is much difference in how migrants are dying that is simply not shown in the Migrant Warning Poster. Men and women[8] are dying at different rates and of different causes; people at varying ages are dying at different rates; people are dying of different causes according to different locations and trajectories. None of this information is presented in the Migrant Warning Poster.

Choosing the Demographic

The migrant women’s elevated risk of death by exposure is the specific demographic and context I chose to represent in a redesign. Although there are dozens of maps that could be redesigned from the Map of Migrant Mortality, migrant women dying of exposure stood out to me because of the astonishing rates women are dying when compared to men. While men are more numerous than women (I counted over 2,800 found men compared to 470 found women), the rate of death by exposure is 34% of all men compared to 63% of all women. The disparity is evident across all land corridors in Arizona with some places having 23% of men dying of exposure compared to 100% of women.[9] Nogales, the land corridor represented in the Migrant Warning Poster, has 37% of men die of exposure compared to 49% of women.[10] One may make the point that since both significant percentages of men and women are dying of exposure, why not create a map that shows the risk of death by exposure for all migrants? I believe that this approach to the redesign may hide the importance of theorizing through difference; that is, it’s important that we recognize the difference in women dying at a higher rate than men.

After it became clear that migrant women are at an elevated risk of death by exposure, I was at a crossroads of where my redesign should go. After all, to draw upon common train of thought in TPC, the redesign is only as purposeful as it is useful. It is not enough to redesign the poster with the same one-dimensional approach as the original. The new map must show potential migrant women the complexity of travel, death, and resources while at the same time fulfilling the spatial goal of a map (Welhausen, 2015). In other words, this new map has to put migrant women as the priority in accordance with what world-traveling advocates: it must be useful while at the same time not universalizing nor can it cause further harm: (Lugones, 2003; Mohanty, 2003)—harm not just in the sense that the map can hide the humanity of those depicted (Dragga & Voss, 2001) but also in the sense that this map can harm migrants by not informing them of the unique dangers of the desert. World-traveling, and the playfulness and reflexivity in its practice, helped me to redesign the poster in a way that can reduce both of these instances of harm.

Anticipating Needs

I world-traveled to the migrant women in the archive to anticipate what they might need from a map. I imagined that the current Migrant Warning Poster might not give women the necessary information to survive. I tried my best to identify with these women, to “understand what it is to be them and what it is to be ourselves in their eyes” (Lugones, 2003, p. 96) while at the same time tasking myself with humanizing the archive in the way Dragga & Voss (2001, 2003) encourages us. In their eyes, I could see that the sea of red dots, scattered ubiquitously about the desert, was both intimidating and unhelpful—what could a migrant do with these dots? I found that offering the names, gender, ages, causes of death, and locations of death could help potential border-crossing women understand the unique dangers to them and others. Names give humanity and perhaps some insight into race and culture to those in the warning poster that could communicate the peril of crossing the desert (Hartman, 2008; Ortega, 2016); gender could relay the fact that women are at an increased risk of death and should take additional precautions before crossing; age shows that it is not only older women dying of exposure but also young women and girls; causes of death and locations of death reflect how different parts of the Nogales land corridor put women at different risks of exposure (some areas may make migrant women more susceptible to dehydration while others to hypothermia, for example). All of these considerations diversify the original map by showing that people are harmed in specific ways.

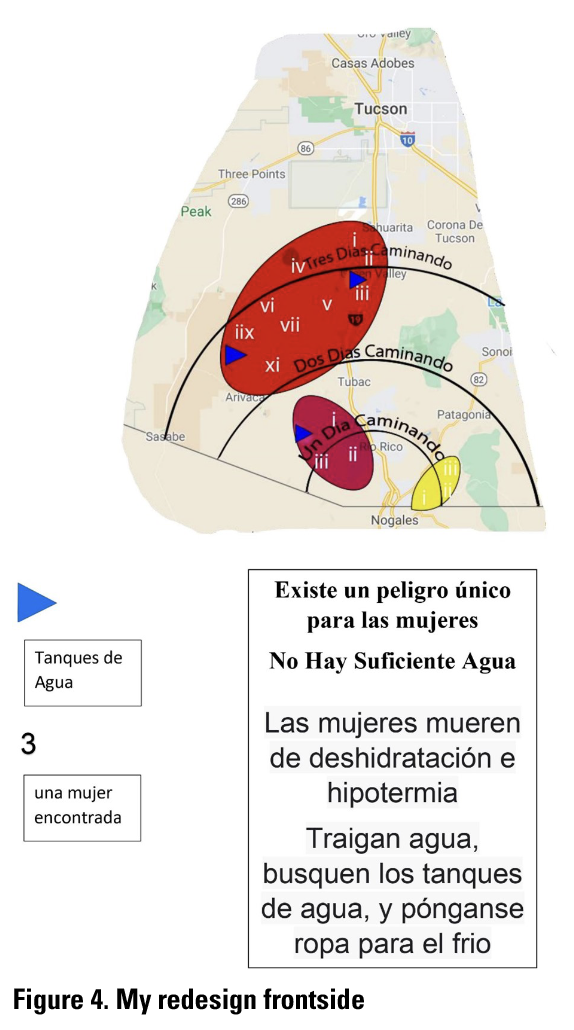

Rationale of Visual Design and Functionality

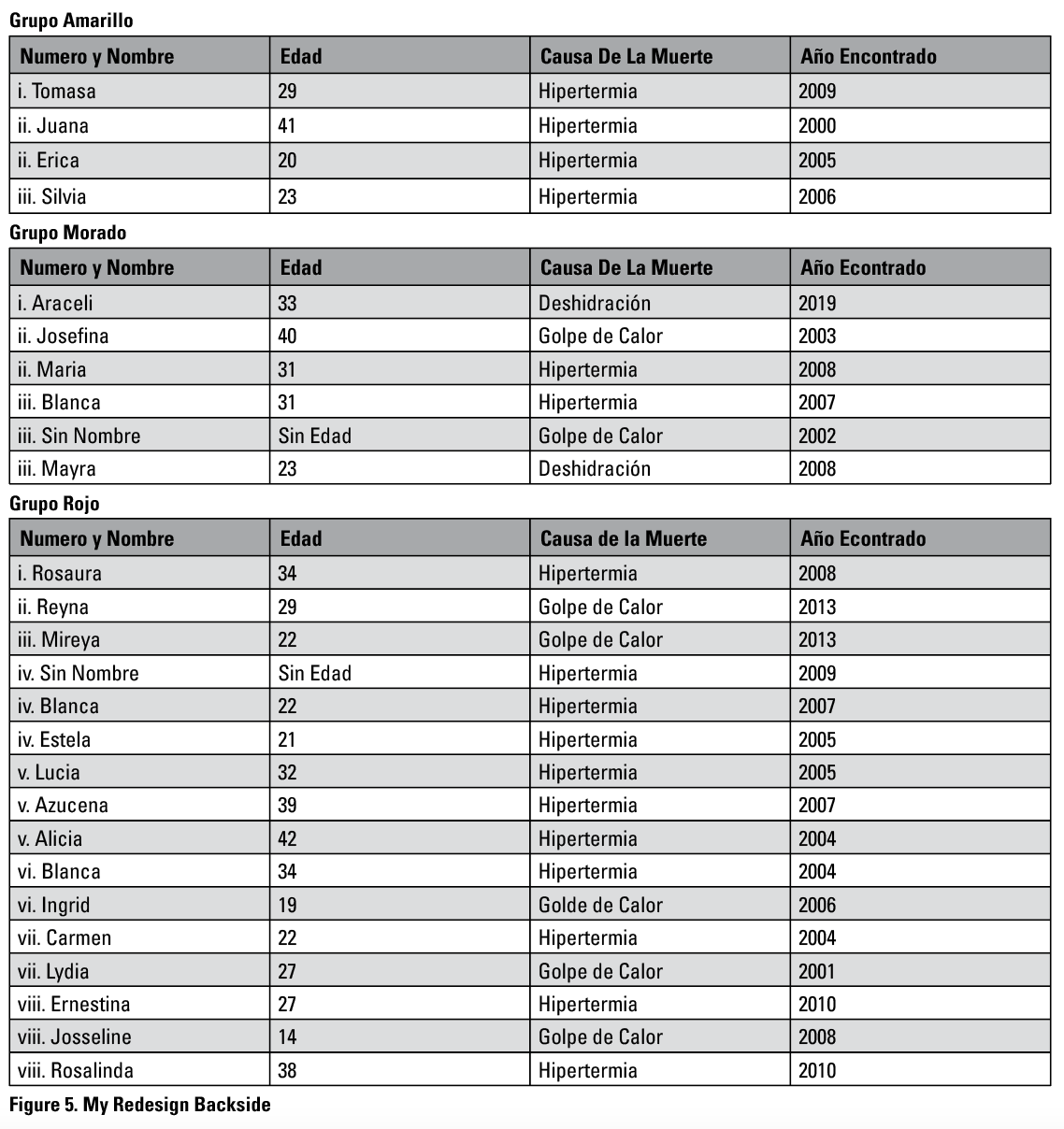

The redesigned map demonstrates how one could improve technical communication through world-traveling to the migrant women in the archive. There are 26 women who have died by exposure in Nogales according to the Map of Migrant Mortality. My goal is to humanize these 26 women while making it clearer to future migrant women that there is an increased risk of dying by exposure. The redesign was made through Photoshop[11] where I made a 1:1 copy of the Nogales land corridor through Google maps when compared to the Nogales land corridor shown in the original Warning Poster. I recreated the time-elapsed markers (Un Dia Caminando, Dos Dias Camindando, etc.) using the original Poster for reference. Then came the question of how to improve the rigidity and dehumanizing red dots. I considered Propen’s (2007) call that we should consider the environment around the people in our rhetorical critique. I opted for three zones that grouped the highest concentration of women: grupo amarillo (yellow zone), grupo morado (purple zone), and grupo rojo (red zone).[12]

Organizing deceased migrant women in zones can better allow potential migrant women to see the most perilous parts of the desert while allowing for the redesign to humanize the 26 deceased women. The original Poster was overwhelming as the sea of red dots made it difficult to distinguish how different parts of the desert effected migrants differently. However, by organizing these women in zones, it becomes clearer that there are different risks associated with the trajectory of travel. For example, all the women who have traveled eastward died of hyperthermia (hipertermia) while dehydration (deshidración) and heat stroke (golpe de calor) become factors when migrants travel westward. This information is valuable in the preparation migrants need when traveling. The other benefit to the groups is the potential to humanize the women in the archive. I replaced the red dots with a numerical system where each woman is assigned a number; that number corresponds with a table on the backside of the redesigned poster. A potential migrant could see a number 1 in the yellow zone on the frontside and then follow that information to the backside to see the name, age, cause of death, and year found. Not only are these 26 women humanized in this redesign, but potential migrants are also given valuable information on the age and cause of death of that person—information that can help a migrant better prepare for travel.

Comparing the Redesign and Original Maps

I’d like to compare the original map and my redesign side-by-side. I mentioned the one-dimensional approach of the original Poster—how the flatness of the red dots and blue flags rhetorically argued that water and the location of deceased migrants are the only important information (Atherton, 2021; Kimball, 2006; Welhausen, 2015) while the red dots practice a Methodological Universalism (Mohanty, 2003). At first glance, my redesign might come across as one dimensional. Afterall, the red dots are replaced by Arabic numbers and the blue flags remain. However, I’d argue that my redesign unflattens the harm and solutions in a way that is more useful. In my world-traveling, I saw that migrant women’s harm was universalized by the red dots. A migrant woman could look at the original Poster and not see the intricacies of how travel and the desert led to different causes of death. My redesign hopefully communicates the specific harm that migrant women can face on their travel. My world-traveling helped me anticipate that migrant women may need to know how gender, trajectory, age, and year become a part of the risk of crossing the Arizona desert. For these reasons, I argue that, while my redesign is still constrained to the physical dimensionalities of a printed map, it unflattens the people in the map in a way not found in the original poster. I hope to donate my redesign to Humane Borders in the near future.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

A playful attitude allowed me to go through the archive with an openness to be surprised. I put aside the mission statement of Humane Borders and their description of the needs of migrants; I put aside my own expectations of what I might find in the archive. I tried my best to listen to those in the archive and anticipate what could help. I world-traveled to many different populations, some of which are not represented in the archive—men, women, pregnant people, children, the elderly, the young, those in the LGBTQ+ community, the problems of whiteness and Blackness and of race in general, and all the intersections of identities that cross borders with their border crossers—and found that each demographic had something to say that wasn’t represented in the original poster. For example, I went through many drafts of a redesign based on my world-traveling. I originally planned to redesign a map for those who are pregnant or with small children to show where one can find baby-safe water and diapers; I was also invested in a redesign showing men that there is a risk of motor vehicle accidents in certain areas as the original poster fails to show how some water stations are only accessible after crossing a busy road. The point is that the playfulness from world-traveling can give technical communicators another tool to listen when our audiences cannot speak or be heard in conventional ways.

A playful attitude allowed me to go through the archive with an openness to be surprised. I put aside the mission statement of Humane Borders and their description of the needs of migrants; I put aside my own expectations of what I might find in the archive. I tried my best to listen to those in the archive and anticipate what could help. I world-traveled to many different populations, some of which are not represented in the archive—men, women, pregnant people, children, the elderly, the young, those in the LGBTQ+ community, the problems of whiteness and Blackness and of race in general, and all the intersections of identities that cross borders with their border crossers—and found that each demographic had something to say that wasn’t represented in the original poster. For example, I went through many drafts of a redesign based on my world-traveling. I originally planned to redesign a map for those who are pregnant or with small children to show where one can find baby-safe water and diapers; I was also invested in a redesign showing men that there is a risk of motor vehicle accidents in certain areas as the original poster fails to show how some water stations are only accessible after crossing a busy road. The point is that the playfulness from world-traveling can give technical communicators another tool to listen when our audiences cannot speak or be heard in conventional ways.

Reflexivity allowed me to understand that the people in the archive are subject to academic fixation and reproduction. Understanding world-traveling means understanding how predatory dominant worlds can be over the marginalized. This predation doesn’t have to be deliberate or malicious, but it happens through the perpetual reproduction of data without the reflexivity that this reproduction may be harming the people in the data. The original poster was not reflexive. It flattened thousands of diverse people into red dots and then printed the map in mass in its distribution to migrants. I hopefully demonstrated what a reflexive researcher could accomplish. I understood my status in a dominant world and how my dominant world kept reproducing harmful data like the one found in the poster. My solution was to halt a 20-year production cycle by looking deeper into the purpose of the poster: who was it for, after all? It is not for researchers but for the migrants who use the map to find water. My reflexivity, practiced through world-traveling, gave me the insight to put migrants first.

My redesign of the Nogales Warning Poster and my practice of world-traveling to migrant women should not be considered a perfect demonstration. It’s far from it. There are constraints. I found questions through my world-traveling that could not be addressed with the information in Humane Borders’ archive; for example, I anticipated that country of origin may be useful for migrant women considering that migrants at the border come from all over Latin America—a practice that could better highlight the intersections of race in these countries. However, I did not have that information. As valuable a methodology world-traveling is when we consider inaccessible audiences, it is still another way to work with what we have. It is a real, grounded methodology put forth by transnational feminists in that we can make valuable contributions in so much as we have valuable information. In other words, world-traveling is not make-believe as some skeptics might claim. It is a way to see through another’s eyes to anticipate what they may need (Lugones, 2003), but what we anticipate can only be fulfilled by the resources we have as researchers. What I hope my demonstration sparks is for other technical communicators to world-travel and to practice transnational feminism in places where we can’t access an audience in traditional ways; the practice could lead us to questions and solutions that we may not have considered otherwise.

My redesign of the Nogales Warning Poster and my practice of world-traveling to migrant women should not be considered a perfect demonstration. It’s far from it. There are constraints. I found questions through my world-traveling that could not be addressed with the information in Humane Borders’ archive; for example, I anticipated that country of origin may be useful for migrant women considering that migrants at the border come from all over Latin America—a practice that could better highlight the intersections of race in these countries. However, I did not have that information. As valuable a methodology world-traveling is when we consider inaccessible audiences, it is still another way to work with what we have. It is a real, grounded methodology put forth by transnational feminists in that we can make valuable contributions in so much as we have valuable information. In other words, world-traveling is not make-believe as some skeptics might claim. It is a way to see through another’s eyes to anticipate what they may need (Lugones, 2003), but what we anticipate can only be fulfilled by the resources we have as researchers. What I hope my demonstration sparks is for other technical communicators to world-travel and to practice transnational feminism in places where we can’t access an audience in traditional ways; the practice could lead us to questions and solutions that we may not have considered otherwise.

A HEURISTIC TO HELP OTHERS GET STARTED

When looking at a potential application of world-traveling in humanitarian contexts:

TPC-Centered Prompts

- What is being said about the population depicted in this data set?

- What is not being said?

- Is there an archive that feeds this data set?

- Where can I go to find out more about the population?

- What worlds are described by all the available information?

World-Traveling-Centered Prompts

- What is the world(s) I inhabit?

- Does my world have an imperialistic drive? Does it conquer the worlds of the marginalized?

- What approaches of a playful attitude can help me navigate that imperialistic drive?

- Would my world-traveling be more so for my gain? Or more so to help others?

- How do I depict my world-traveling to others as to continue building the scholarship?

- How do I keep the helping of the marginalized at the forefront of the scholarship?

REFERENCES

Agboka, G. (2013). Participatory localization: A social justice approach to navigating unenfranchised/disenfranchised cultural sites. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22(1), 28–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2013.730966

Atherton, R. (2021). “Missing/Unspecified”: Demographic data visualization during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 35(1), 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651920957982

Bacha, J. A. (2018). Mapping use, storytelling, and experience design: User-network tracking as a component of usability and sustainability. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 32(2), 198–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651917746708

Colton, J. S., & Holmes, S. (2018). A social justice theory of active equality for technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 48(1), 4–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616647803

Cui, W. (2019). Rhetorical listening pedagogy: Promoting communication across cultural and societal groups with video narrative. Computers and Composition, 54, 102–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2019.102517

Dragga, S., & Voss, D. (2001). Cruel pies: The inhumanity of technical illustrations. Technical Communication, 48(3), 265–274.

Dragga, S., & Voss, D. (2003). Hiding humanity: Verbal and visual ethics in accident reports. Proceedings/STC, Society for Technical Communication Annual Conference, 50(1), 457–461.

Haraway, D. J. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism of partial and the privilege. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599.

Jones, N. N. (2016). Narrative inquiry in human-centered design: Examining silence and voice to promote social justice in design scenarios. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(4), 471–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616653489

Jones, N. N., & Walton, R. (2018). Using narratives to foster critical thinking about diversity and social justice. In Key Theoretical Frameworks: Teaching Technical Communication in the Twenty-First Century (pp. 241–260). Utah State University Press.

Kimball, M. (2006). London through rose-colored graphics: Visual rhetoric and information graphic design in Charles Booth’s maps of London poverty. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 36(4), 353–381. https://doi.org/10.2190/K561-40P2-5422-PTG2

Lugones, M. (2003). Pilgrimages/Peregrinajes: Theorizing Coalition Against Multiple Oppressions. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Mays, R. E., Walton, R., & Savino, B. (2013). Emerging trends toward holistic disaster preparedness. ISCRAM 2013 Conference Proceedings – 10th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, May, 764–769.

Mohanty, C. T. (2003). Feminism without Borders. Duke University Press.

Ortega, M. (2016). In-Between: Latina Feminist Phenomenology, Multiplicity, and the Self. State University of New York Press.

Petersen, E. J., & Walton, R. (2018). Bridging analysis and action: How feminist scholarship can inform the social justice turn. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 32(4), 416–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651918780192

Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship, (2003) (testimony of Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship).

Propen, A. (2007). Visual communication and the map: How maps as visual objects convey meaning in specific contexts. Technical Communication Quarterly, 16(2), 233–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572250709336561

Ramler, M. E. (2021). Queer usability. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(4), 345–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2020.1831614

Ratcliffe, K. (2005). Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness. Southern Illinois Press.

Vats, A. (2014). Racechange is the new black: Racial accessorizing and racial tourism in high fashion as constraints on rhetorical agency. Communication, Culture & Critique, 7(1), 112–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/cccr.12037

Walton, R., Mays, R. E., & Haselkorn, M. (2016). Enacting humanitarian culture: How technical communication facilitates successful humanitarian work. Technical Communication, 63(2), 85–100.

Welhausen, C. A. (2015). Power and authority in disease maps: Visualizing medical cartography through yellow fever mapping. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 29(3), 257–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651915573942

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gabriel Lorenzo Aguilar (gla22@psu.edu) is a PhD student at Penn State studying Rhetoric and Technical Communication. His main research interest is in investigating how to improve the technical communication between humanitarian organization and the recipient of humanitarian aid. Additional areas of focus for Gabe are in Chicanx, border, and feminist rhetorics.

Appendix

List of Redesigns that could be created from World-Traveling to the Map of Migrant Mortality

- Men Drowning

- Men’s Death by Gunshot

- Men’s Motor Vehicle Accidents

- Women’s Death by Pregnancy Complications

- Common Causes of Death throughout Different Land Corridors

- Common Causes of Death for Children

- Locations with the Highest Concentration of Skeletal Remains

- Comparative Map that Shows the Proximity Men and Women Die compared to Water Stations

- A Map that Shows the Causes of Death that Pertain to Certain Seasons of the Year

- A Map that Shows the Leading Causes of Death throughout Certain Decades

- A Map that Shows if Deaths have Lessened since the Implementation of Water Stations

- A Map that Shows the Relocation of Water Stations and the Lives-lost that Surrounds them

- And many others.

Suggested Reading on World-Traveling and Narrative Inquiry

Dewart, G., Kubota, H., Berendonk, C., Clandinin, J., & Caine, V. (2020). Lugones’s metaphor of “world travelling” in narrative inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(3–4), 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419838567

[1] Lugones (2003) has received criticism over her assertation that all people can world-travel as it can overlook the importance of race, whiteness, and Blackness in the ability to travel and enter another’s world.

[2] Playfulness may come across as an inappropriate term especially in the context of my writing about dying migrant women. The term “playfulness” is used consistently in Lugones (2003) as a characteristic of being open to surprise and to be unconquering as we visit other worlds. Lugones (2003) clarifies that playfulness here is not about competition or winning; rather, it’s about accepting that our perspectives of marginalized worlds are often shaped by dominant worlds to make the marginalized seem lesser and other.

[3] My claim here is not to say that those who travel from marginalized worlds do not collect data; surely, the brown custodian who works for the middle-class white man scholar has collected data about this world of power: there is data collection on how privileged worlds orient their spaces, what people in privileged worlds expect in their services, and what people in privileged worlds find valuable or invaluable in their worlds. The brown custodian collects this data and distributes it in the marginalized worlds they visit. What I am claiming is that because we, as scholars of TPC, to some extent inhabit and frequently visit worlds of power (Lugones, as both a scholar and woman of color, included), we should understand how we gather data from marginalized worlds. Understanding can help TPC be better, and more ethical, in our data collection from marginalized worlds and its peoples.

[4] It’s important to note that while Lugones does inhabit worlds of power and marginalized worlds, she is still subjected to marginalization in the worlds of power. She is still a woman of color nonetheless and is subservient in these powerful worlds.

[5] Note that there are three categories listed under “gender”: male, female, and undetermined. The current iteration of the map of migrant mortality most likely determines gender on a person’s genitalia (although this method is not specifically mentioned anywhere on Humane Border’s website). People with penises are coded as male and people with vaginas are coded as female. The undetermined category is reserved for bodies that are too far decomposed to be accurately sexed. There is no mention of possible transgender migrants, and the argument to include transgender migrants in the data, while in support from this author, is beyond the scope of this project. Furthermore, I will report females as women and males as men. I believe women and men as categories further pushes the argument to diversify datasets.

[6] I have found that across all corridors 63% of all found women have died by exposure compared to 34% of all found men. When looking at individual corridors, Sasabe has the largest gap between women and men’s death by exposure with 100% of women dying from exposure compared to 23% of men; the smallest gap is in Sasabe with 53% of women dying from exposure compared to 38% of men.

[7] A corridor is a sliver of Arizona in which a number of water stations are placed in the predicted trajectory of migrants’ travels. Corridors are used in the creation of Migrant Warning posters as four of the most frequented corridors (Nogales, Lukeville, Sasabe, and Douglass) have been chosen by Humane Borders to represent water stations and deceased migrants. This project will focus on the Nogales corridor shown in the Nogales warning poster.

[8] The Map of Migrant Mortality only regards gender in terms of male and female. I prefer men and women and would also add that there should be additional categories for trans- and non-binary people.

[9] This land corridor, Berandino, saw 3 of 3 women die of exposure while 3 of 13 men died of exposure.

[10] Nogales saw 25 of 51 women die of exposure compared to 107 of 286 men.

[11] Disclaimer: I am not a graphic designer nor am I an expert in Photoshop. However, while the aesthetic of this redesign needs much improvement, I believe the major contextual changes between the original Warning Poster and my redesign is demonstrative enough where a technical communicator can apply the practice to their own redesign.

[12] Note that these colors don’t present anything meaningful beyond their intended function. They are a tool to organize the many bodies that were once represented by red dots.