doi: https://doi.org/10.55177/tc105639

By Daniel P. Richards and Sonia H. Stephens

ABSTRACT

Purpose: The authors present the results of an empirical study investigating strategies for localizing risk messaging pertaining to sea-level rise (SLR) and flooding. We argue that continued testing is necessary to help bolster arguments about the value of localization design practices and that technical communication as a field is positioned well to lead the charge in such testing.

Method: The authors conducted a mixed methods research study to discover whether video stories from local residents change user perceptions or concern about SLR as a risk. More than 100 survey responses were collected to track any relation between concern and understanding and modality of storytelling, and focus groups were led with 13 survey respondents to add a deeper understanding of effective strategies for localization.

Results: The data show that video and textual storytelling do not differ as much as expected in the context of decision-support tools for SLR.

Conclusion: Although video narratives for localization did not affect user perception or concern about SLR more strongly than text quotes did, participants felt that the localization efforts were compelling. Participants suggested ways in which both video and textual narratives might be more effectively used to support audiences’ understanding of SLR. As a result of their suggestions, we note future research topics and testing methods to explore risk localization best practices.

KEYWORDS: Risk communication, Sea-level rise, Localization, Video narratives,

User experience

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- User experience testing results in this study find that videos are not substantially more effective than text in creating an effective and localized risk communication.

- More refined methods need to be implemented for conducting user experience testing for localization in risk communication, e.g., through scenario-based testing.

INTRODUCTION

Few topics in technical communication (TC) straddle global and local regions with more urgency than climate change and sea-level rise (SLR). Scholars and practitioners in risk and environmental communication have the challenging goal of scale, rendering global data on climate change and SLR meaningful to the specific local communities that will be most affected. This problem of scale is more challenging because much climate change and SLR data are derived from modeling future conditions, which present a temporal disconnect from present-day lived experience (Herring et al., 2017). In coastal communities, the communicative challenges of spatial scale and temporal immediacy can sometimes be bridged by linking observed phenomena (e.g., street flooding, stronger hurricanes) with global trends to facilitate residents’ buy-in and engagement with mitigation practices and resilience mindsets. Such engagement can, in turn, support individual and community agency in affected areas (Schneider & Walsh, 2019).

In this study, we focus on web-based SLR communication through which technical communicators can intervene in risk communication by adding a local, human dimension to global, impersonal data. Risk communication researchers have examined ways in which place-centered information visualization can motivate audiences’ engagement with and concern for environmental hazards. For example, audiences who view augmented-reality simulations of the place-based impacts of climate change experienced increased concerns about climate change and interest in learning more about flooding risk and mitigation options (Moser et al., 2016). Other research, however, has found that, although interacting with mapped climate data led to stronger certainty that climate change is real, users’ own proximity to a specific location did not affect climate-change-related attitudes and beliefs (Herring et al., 2017). Additional research (e.g., Moser, 2010; Nicholson-Cole, 2005; Retchless, 2018) has pointed to the complexity of this communicative challenge.

Other studies have examined the role of narrative in environmental risk communication. Research on textual narratives for risk communication analyzed the differences in how laypeople, particularly those in indigenous communities, share narratives about climate change, as compared to the factually-oriented narrative style that Western science-oriented organizations tend to favor (Lejano et al., 2013). In further testing differences in narrative structure and forms of address between lay and scientific communication in emergency text messages, researchers found that residents’ concern and motivation to act are stronger after viewing messages with a more personal narrative style (Lejano et al., 2018). Taking a different approach, Butts and Jones (2021) developed an augmented reality app for a specific location; the app incorporated both textual and visual narrative elements—including elements focused on environmental risk—as a deep mapping project intended to share multiple perspectives of a place.

In this paper, we explore how localization can help us develop more engaging, informative, and audience-empowering environmental risk communications. Within TC, localization has been discussed primarily as a process to tailor products to the needs of specific cultural groups by careful consideration of function and application to real-world tasks and to sociocultural contexts (Sun, 2006). However, designing for these aspects of localization is complex, particularly for sociocultural factors that cannot be addressed by language translation (e.g., Agboka, 2013). Therefore, technical communicators have called for adopting user-centered and participatory design strategies as a partial solution to the challenges of cultural localization (Agboka, 2013; Shivers-McNair & San Diego, 2017; Sun, 2006).

Localized environmental risk communication efforts need to consider a range of place-specific social, economic, and physical factors. For example, many coastal communities thus far experience SLR primarily as nuisance flooding that impacts quality of life or as erosion that impacts property values, whereas life-threatening flooding that occurs during storms is rare. However, long-term residents’ experiences of rare flooding events may be a good guide as to the types of impacts that residents will experience on a more frequent basis as SLR accelerates over the next few decades (Sweet et al., 2022).

In this study, our goal is to examine the assumption that adding the voices of local residents to a data-driven SLR visualization tool via videos makes environmental risk communication more effective as a localization technique. Although TC work supports the assumption that local perspectives can help audiences connect with large-scale data, research that tests the efficacy of localizing interventions is needed to understand what might be achieved by these efforts. The relationship between the local experience of environmental problems and the global factors—both environmental and societal—that cause those problems is complex. In the context of designing environmental monitoring technologies, “there is a compelling need to oscillate from local participants’ experiences [to a more] globally connected experience” (Sackey, 2020, p. 45).

We focus our efforts on communication that makes use of interactive online mapping tools that are intended to help local communities understand their SLR-related risks. Specifically, we look at the effects of localization on website users’ concern and perceptions of personal agency about SLR. This study builds on previous research in which we theorize about localization in the design of a SLR communication tool by adding video-recorded personal stories about flooding to a national interactive SLR map using a story mapping tool (Stephens & Richards, 2020). In this study, we move from design to testing, and we share the results of user experience (UX) research investigating the unique effect of inserted videos of local residents on user perceptions of risk and attitudes towards climate change and SLR. Our specific questions are:

- Do video narratives of local residents sharing their concerns about SLR help other community members relate to its potential effects on their communities?

- How, if at all, do the effects of using video narratives for localization differ from the effects of using residents’ quotes for localization?

- What particular features and elements might make video narratives more effective in communicating about the potential effects of SLR on a community?

Our overall objective is to provide guidance for TC researchers and practitioners who are interested in incorporating video narratives into their localization practices, particularly in the context of environmental or location-specific risks.

METHOD

Methods were evaluated by the first author’s Institutional Review Board and approved for this study. We obtained user feedback on two versions of the website SLR Stories using a two-part procedure. First, we distributed an unmoderated survey that targeted certain aspects of the two websites and asked users to comment on website design and their interpretation of the website information. The survey helped us identify any differences in levels of concern between those exposed to the video version and those exposed to the text-only version (which excerpted printed quotes from the video transcripts). Second, we followed up with participants to conduct focus groups to parse out the qualities of the videos or text that engaged the participants and to investigate those qualities. Given careful attention to process and participant interactions, focus groups encourage the free sharing of viewpoints in a conversational format, which can lead to unplanned insights and minimize researcher biases (Lune & Berg, 2017).

Methods were informed by A/B testing, commonly used in UX (Lindberg, 2020) to show two or more variants of a design to users at random to identify which one performs better. In our case, we were not interested in which one performs better in terms of efficiency or in terms of traditional usability metrics. We used A/B testing to isolate the effect of video stories in terms of levels of concern about the risk of SLR and flooding in the region at hand.

SLR Stories Websites

Two modified versions of the SLR Stories website (described in Stephens & Richards, 2020) were created: one with videos of local residents talking about their SLR-related concerns and one with quotations (in text) from local residents (instead of videos). Both versions of the website were constructed with Esri’s Story Map software and consist of a series of story segments that users scroll through. The video version (Richards & Stephens, 2021a) contained four segments:

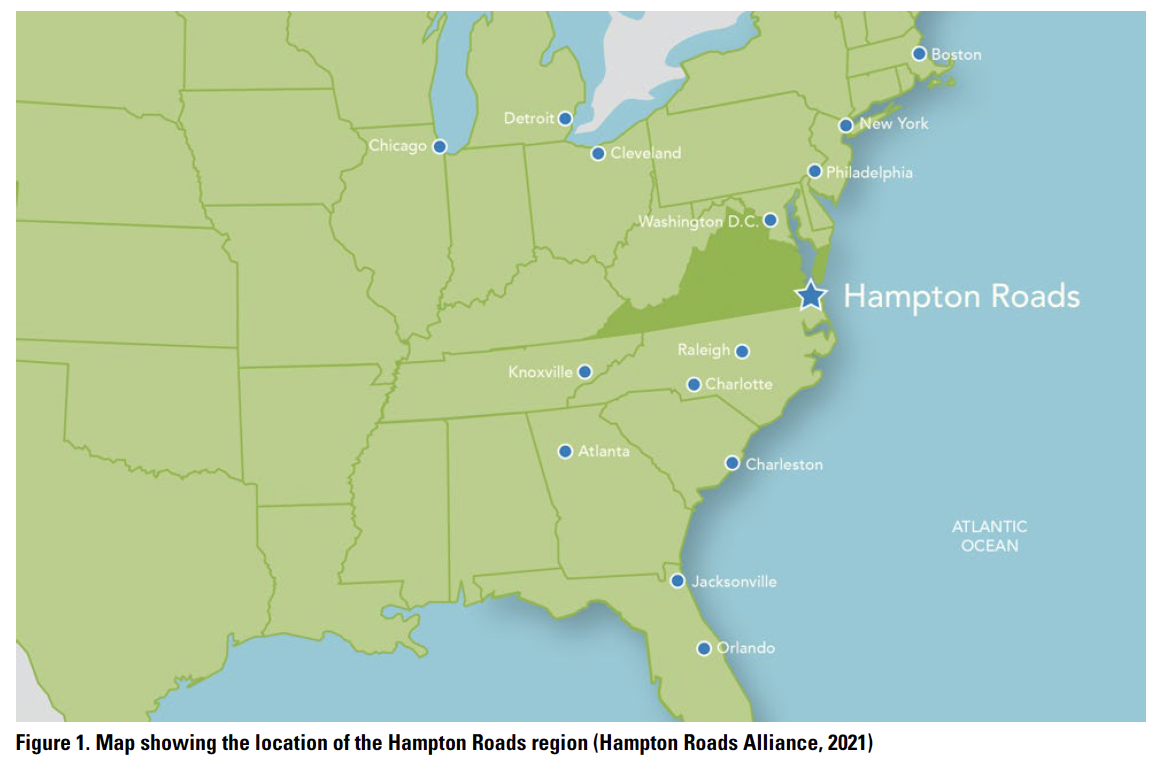

- Description of the website, introduction to the project, and photo of Norfolk, in the Hampton Roads region of southeast VA, USA (see Figure 1 for geographical location).

- Description of SLR projections for the Hampton Roads area, interactive NOAA SLR Viewer map, description of how to use the map, and short video interviews of four area residents.

- List of actions readers can take regarding SLR and photo of the Norfolk beach.

- Contact page for the authors and photo of a seaside historic site.

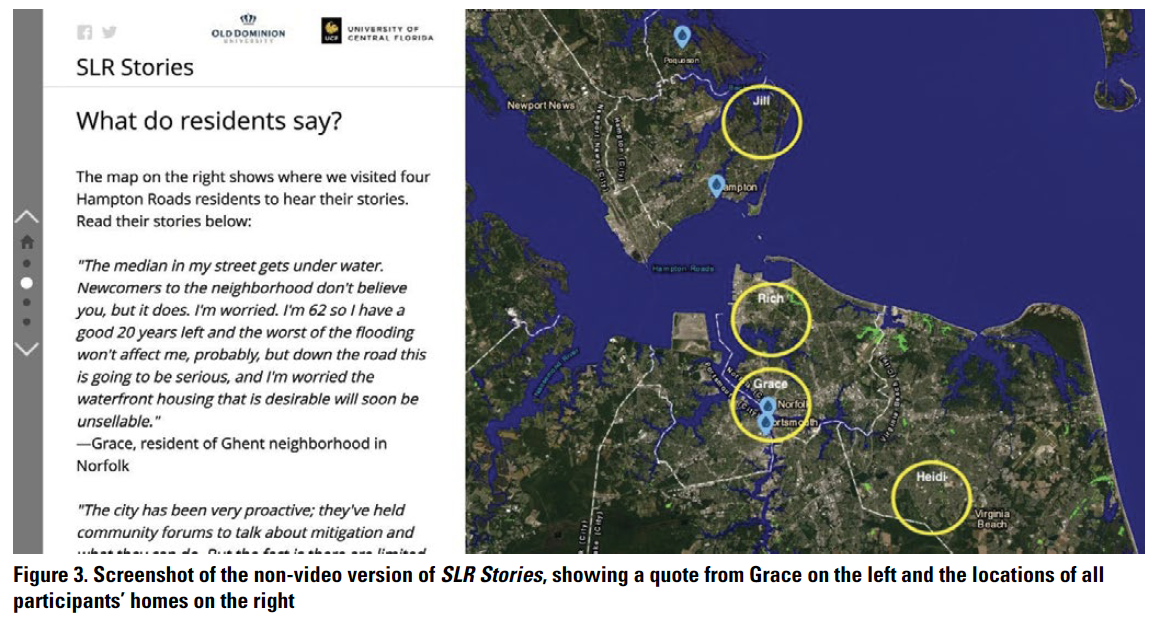

In the non-video version (Richards & Stephens, 2021b), the videos are replaced with a single quote from each resident and a non-interactive map showing the locations of the interviewees’ homes. All other text and images are the same. (See the video and non-video versions of the site in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively.)

In the non-video version (Richards & Stephens, 2021b), the videos are replaced with a single quote from each resident and a non-interactive map showing the locations of the interviewees’ homes. All other text and images are the same. (See the video and non-video versions of the site in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively.)

UX Test

UX Test

The first part of the project was a UX test consisting of user feedback on the website and an accompanying survey. Participants were recruited by convenience sampling from among the student population of the first author’s institution. The website’s primary target audience is coastal residents of Hampton Roads, Virginia; not all UX test participants were Hampton Roads residents, but all focus group participants (in the second part of the study) were. Two different recruitment requests were sent to faculty in the department: one with the link to the video version and the other with the link to the non-video version. Faculty were asked to share the recruitment request that they received with their classes and offer extra credit to students who participated. A total of 168 students participated in the UX walkthrough and survey.

We eliminated responses of less than 21 seconds (using Qualtrics’ time-on-task metric), leaving 52 responses for the video site and 52 responses for the non-video site. We chose the 21-second cutoff for two reasons: we thought it best for the sake of comparison to have the same number of participants in each group, and anything less than ~20 seconds indicated that the participants did not engage with the video (even those that were 20–30 seconds likely did not get the full video experience). Due to pandemic restrictions, the survey was unmoderated; therefore, it was expected that participants would move quickly through it.

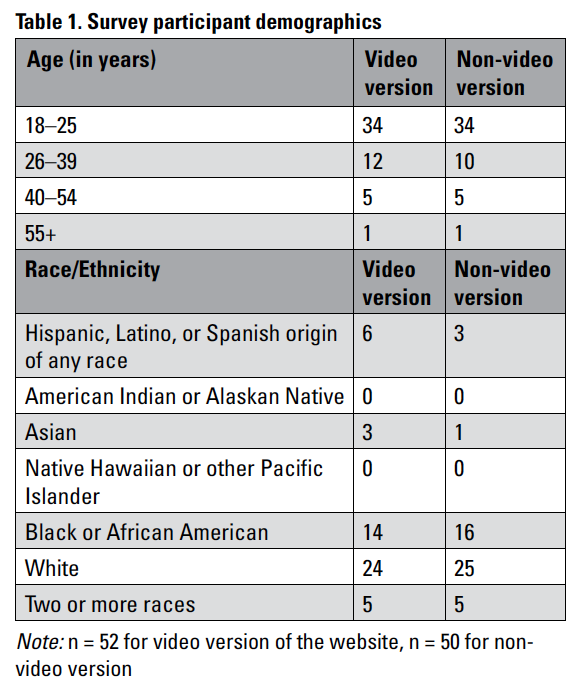

Seventy-eight participants were located in Hampton Roads (38 for the video version and 40 for the non-video version); 19 were in VA but outside Hampton Roads (11 video, eight non-video); and five were outside VA (three video, two non-video). Participants’ racial and ethnic demographics (Table 1) generally reflected the demographic breakdown of the Hampton Roads region, though our study had a slightly lower percentage of white participants than would be expected in a random sampling of the region. We acknowledge issues of access and privilege in our study, as our participants, although racially and ethnically diverse, are relatively privileged, with access to technology, moderate educational levels, and the means to take action. In this respect, our participants might not be reflective of community residents who lack that same level of privilege.

Participants were first asked to read the website text and interact with the interactive SLR viewer while answering questions aimed at characterizing their understanding of the causes of SLR, its current effects on Hampton Roads, and its possible global and local effects. Questions were divided among those that could be answered by interacting with the website and those that assessed broader understanding of the causes of SLR (modified from Priestly et al., 2021).

Next, participants were asked to either watch the videos or read the quotes, depending on the version of the website they were viewing. After reviewing the content, participants were asked about their levels of concern with SLR and their opinions about its causes, whether they had been affected by SLR and if so how, and if they had taken or anticipated taking actions to mitigate or adapt to it within the next 5–10 years and if so what actions. Finally, they were asked for general comments about the project and whether they would be interested in participating in a future focus group discussion.

Focus Groups

Thirteen participants who indicated interest were selected from among the UX survey respondents, and three focus groups, each of four to five people, were conducted over Zoom. Participants were selected to obtain a mix of those who had viewed the video website and the non-video website during the UX walkthrough in each focus group session.

Focus groups were moderated by the first author, who used a semi-structured, open-ended interview guide to prompt discussion of participants’ ideas. Throughout the discussion, he remained friendly and non-judgmental and maintained a positive rapport with participants. He opened focus groups with a description of the project’s purpose, reminded participants that they had recently filled out a survey about the project, and described focus group procedures, including a request that participants treat the discussion as confidential. Participants were then asked to give their first names, the town they lived in, and something they liked about living in the area.

Participants were briefly shown the SLR Stories website to remind them about its structure. Several quotes from the non-video website were read, and participants who had viewed that website were asked what they recalled thinking and feeling about the quotes. Then participants were shown one video from the video website and asked what they recalled thinking and feeling about the video and the concerns raised by the speaker. Participants who had viewed the non-video website were asked whether they would have found videos to be more interesting or relatable than quotes.

After participants responded to the video, the moderator shared three general results about the survey: the number of participants, the overall responses to a question about whether people felt concerned about SLR in Hampton Roads, and the overall responses to whether people believed that they would need to take any actions to mitigate or adapt to SLR in the next 5–10 years. Focus group participants were asked whether they recalled how they answered that question, why they answered that way, and whether they might answer it differently now.

Finally, participants were asked about their concerns for SLR in the region, whether they had any suggestions for making the resident stories on the SLR Stories website more effective to help people understand the possible effects of SLR in Hampton Roads, and whether they thought other types of information might be more effective. To conclude, they were asked whether they had any final thoughts about SLR communication, this project, or the focus group process.

RESULTS

Our results include outcomes from UX surveys and from focus groups.

Survey Results

The survey contained three sets of questions. The first set was aimed at characterizing participants’ understanding of the causes of SLR, its current effects on Hampton Roads, and its possible global and local effects. First, when asked how much sea level had risen in the last 100 years in both Hampton Roads and globally, the video and non-video groups showed no major patterns of difference. Both groups selected a wide range of responses, with only 21% correct responses to the question about historic SLR in Hampton Roads (>12 in.) and 24% correct responses to the global question (6–8 in.). When asked to select the top three contributors of SLR from a list, ~61% selected at least one correct “top three” contributor (melting land-based ice sheets, melting glaciers, and thermal expansion of water). The uncertainty or misconceptions in participants’ preexisting knowledge was similar to that reported elsewhere in the literature (Priestly et al., 2021). An additional 13% selected land subsidence (sinking), a primary driver of SLR in Hampton Roads but not globally; this was also the only response that varied substantially (25 video viewers versus 15 non-video viewers) between groups.

In the second set, participants were directed to explore the SLR Viewer tool (developed by NOAA) on the right side of the webpage, and particularly the slider in the middle of the page that allows users to increase or decrease water levels. When asked to select the scientifically credible maximum possible amount that sea level could rise in Hampton Roads by 2050, 37% of participants answered correctly (up to 3 ft), with slightly more non-video participants answering correctly. When asked to select the most likely amount that sea level could rise in Hampton Roads by 2050, only 19% of participants answered correctly (up to 3 ft).

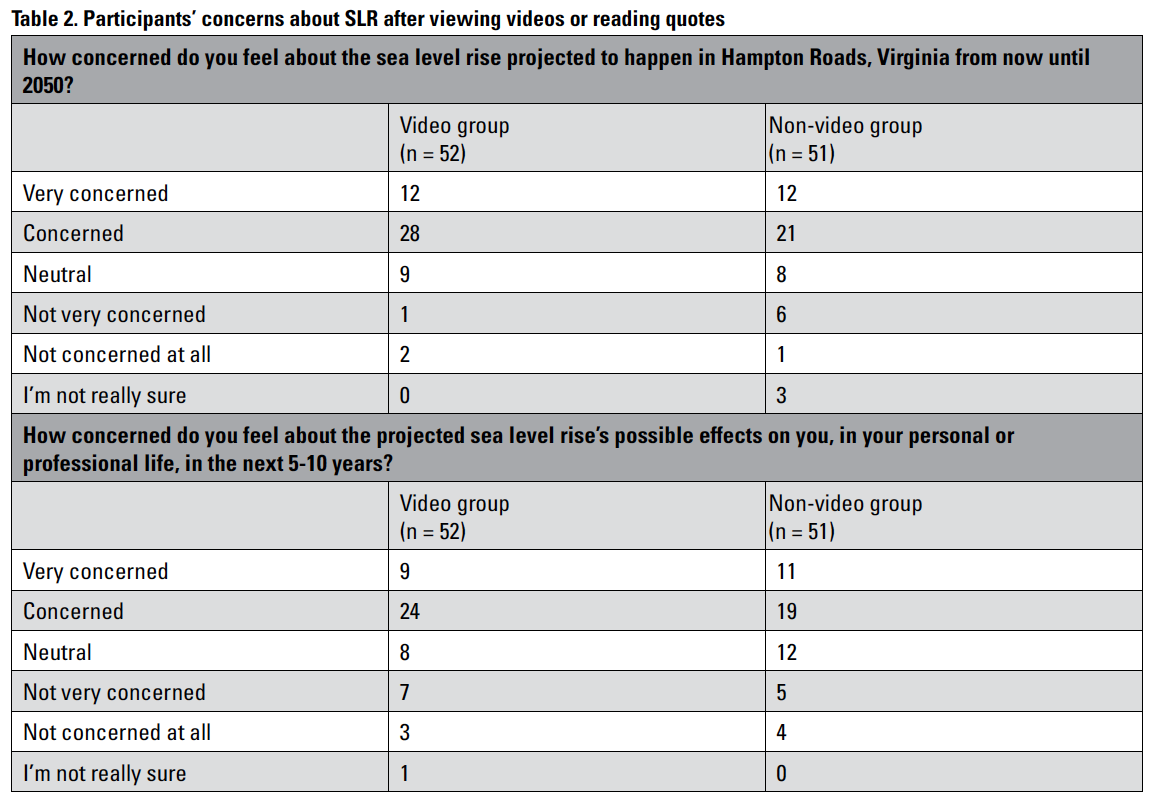

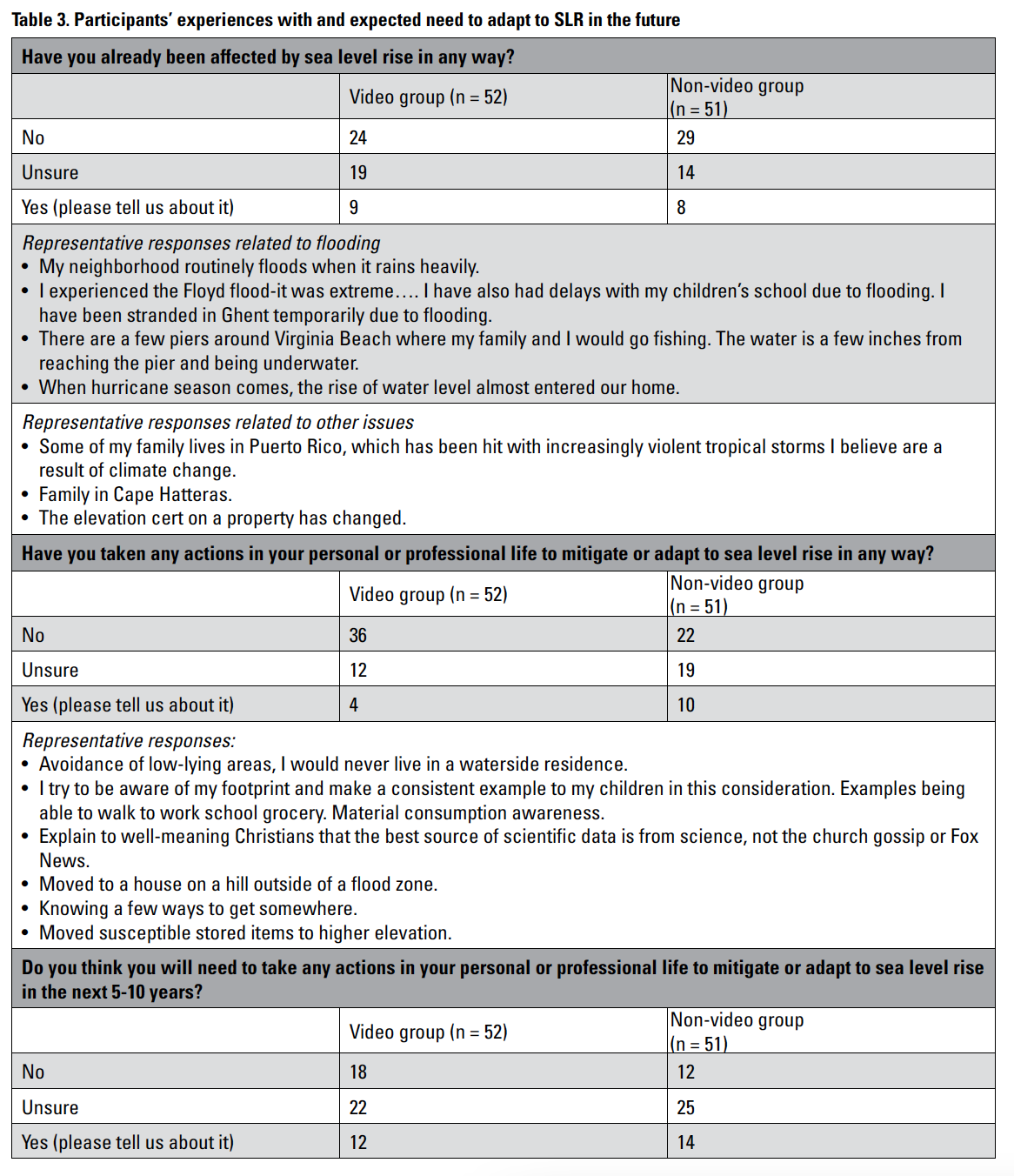

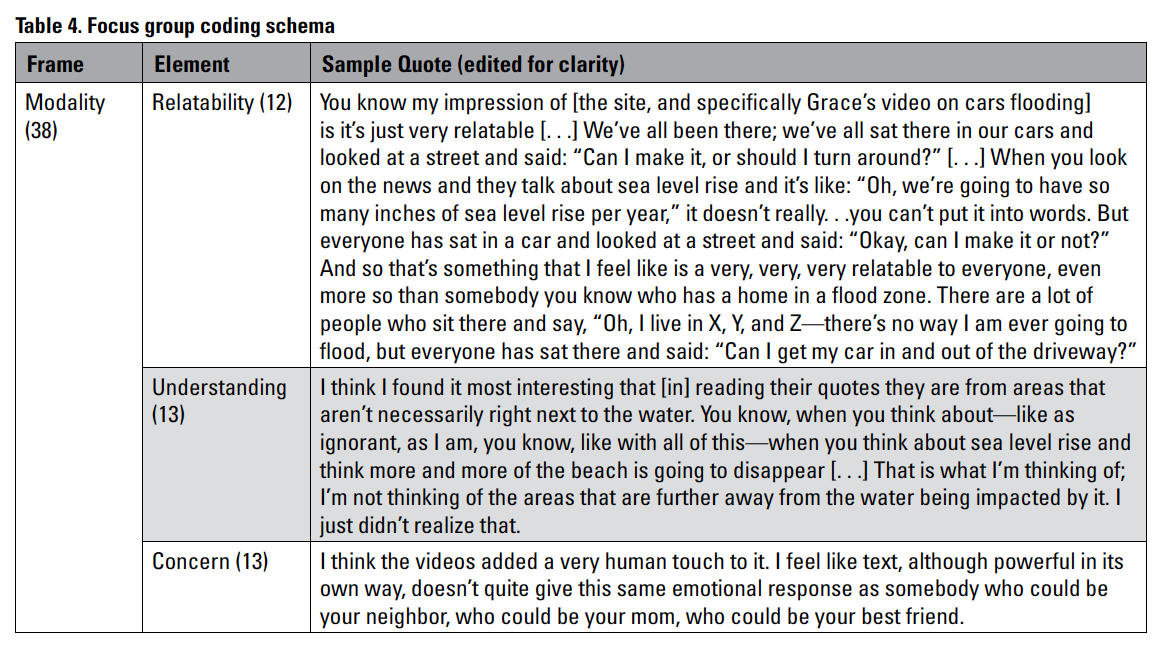

In the third set, participants were directed to interact with the personal narratives from local residents. The video group was directed to watch the videos, and the non-video group was directed to read the quotes from local residents along the left side of the SLR Stories webpage and observe how the right side identifies their locations. Then both groups answered the same questions about their concerns for (Table 2) and personal experiences with (Table 3) SLR.

When asked how concerned they felt about the projected SLR for Hampton Roads from now until 2050 (Table 2), more participants from the video group reported being “concerned” than those from the non-video group (28 vs. 21) and fewer reported being “not very concerned” (1 vs. 6). When asked about the projected SLR’s possible effects on them in the next 5–10 years, more participants from the video group reported being “concerned” than those from the non-video group (24 vs. 19) and fewer reported being “neutral” (8 vs. 12). Overall, participants were more concerned about the projected SLR by 2050 than about its effects on them in the next 5–10 years.

When asked if they had been affected already by SLR, 51% of participants said “no” and 32% were “unsure,” with more video participants being unsure and more non-video participants saying “no” (Table 3). Most examples of being affected that they shared related to flooding. When asked whether they had taken any actions to mitigate or adapt to SLR in any way, 56% of participants said “no” and 30% were “unsure,” this time with more non-video participants being unsure or saying “yes” and more video participants saying “no.” Examples of actions that they shared included identifying alternate transportation routes, considering flooding while looking for housing, and taking eco-conscious actions or holding environmentally oriented conversations with others. Finally, when asked whether they expected to need to take any actions to mitigate or adapt to SLR in the next 5–10 years, 29% of participants said “no,” 46% were “unsure,” and 25% said “yes,” with more video participants than non-video participants saying “no.” Actions that they expect to take include considering flooding while looking for housing, taking more eco-conscious actions, participating in community response efforts, and considering flooding in their future work locations.

Finally, participants in both groups were asked, “Do you have any final comments on this research or the issues raised in it?” Responses addressed

Finally, participants in both groups were asked, “Do you have any final comments on this research or the issues raised in it?” Responses addressed

- the importance of this issue (e.g., “. . . this is a serious topic that should be talked about more.”)

- uncertainty about where to find accurate information (e.g., “. . . I feel rather uninformed on the issue, an[d] I’m not sure where to get accurate information.”)

- concerns about societal priorities (e.g., “Don’t worry, we will use our energy (literally) to solve math problems on a computer for “coins” to trade for money. . .”)

- possible personal responses (e.g., “. . . my major and minor are creative writing and environmental science respectively so I might write some science fiction on the subject of global warming and climate change.”)

- misconceptions about the underlying science (e.g., “ If you have a cup of water with ice and the ice melts. . . the water level is still the same. I would assume the same principle applies.”)

- concerns about impacts (e.g., “I am very concerned about the potential for pollution and impact to industry should industrialized areas become flooded”)

- comments on their proximity to the issue (e.g., “As someone who doesn’t live or have family in that area it is more difficult for me to feel personally affected,” “It’s something to think about because I’m living so close to the water now.”).

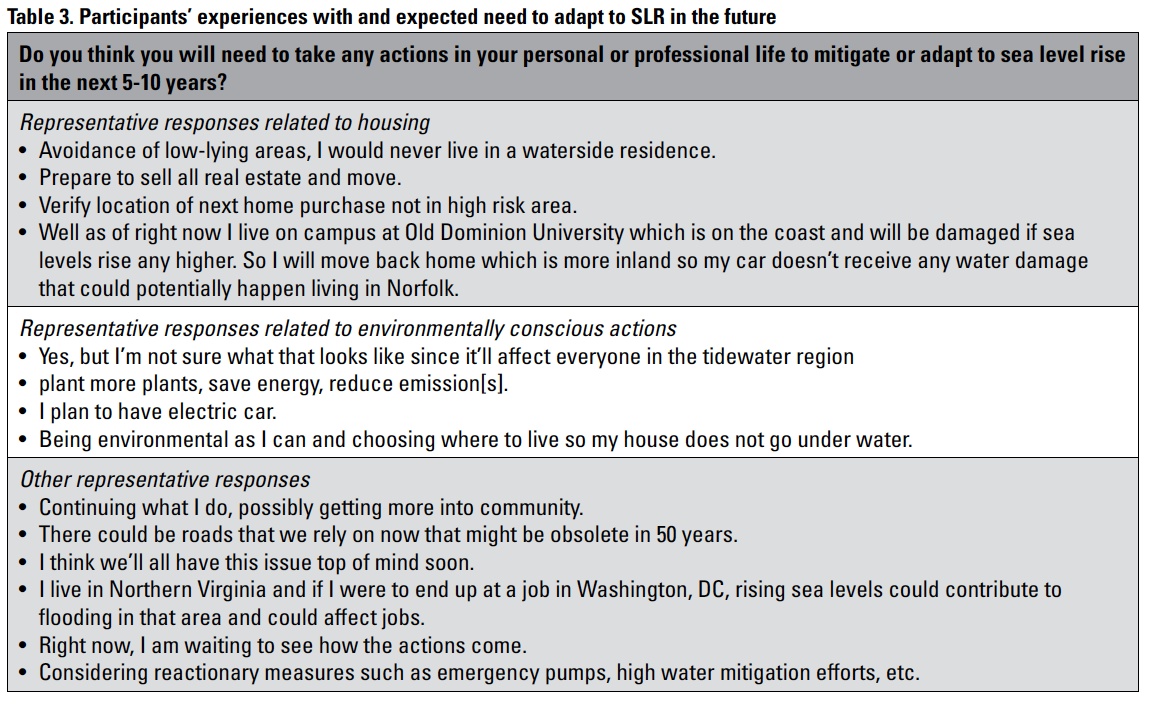

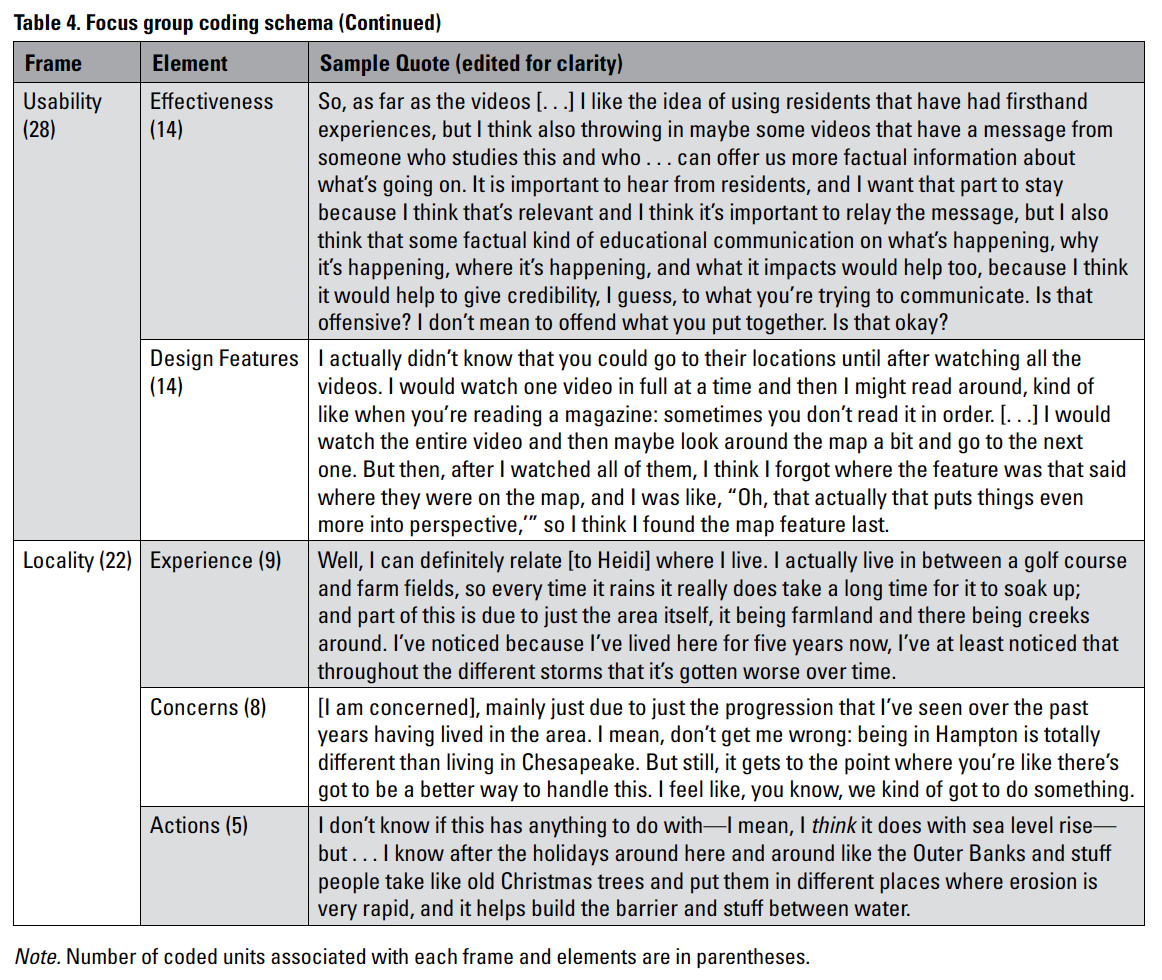

Focus Group Results

Focus group transcripts were coded using guidance in the field on coding verbal data (Geisler & Swarts, 2019); the overarching framework was focused on relationships coding (p. 124), with specific attention being paid to the relationships evident and emerging between the participants and the two types of narrative localization strategies. As such, the coding schema (p. 125) was based loosely on the structure of the focus group questions, but with modality (video vs. text) emerging as a more dominant frame given the way the moderator-led discussion and with the moderator consistently trying to lead discussion back to connecting experiences and usability to the integration of stories in the sites. (Table 4 gives an overview of the three main coding frames and the elements within them, providing representative excerpts to support each.) Emphasis was placed on verbal data that linked participant concern directly to the two localization strategies presented on our sites.

Note. Number of coded units associated with each frame and elements are in parentheses.

Note. Number of coded units associated with each frame and elements are in parentheses.

Focus groups were designed to gather more detail about particular user experiences with the two sites, with the narrower goal of better understanding the role of videos in the design of localization in the context of flood risk. Because participants who used either the video or the text version were grouped together in the focus groups, the investigators were able to gather a more qualitative, descriptive understanding of how users perceived the two strategies. Results are grouped by three frames: modality, usability, and localization.

Modality

In the first portion of the focus group, participants reviewed the sites and then were asked to recall their feelings about the videos and quotes; they were asked if they could relate to the shared concerns, if they understood how SLR might affect residents, and if they felt more concerned after engaging the stories. From the participants’ responses, the coding elements that emerged took the form of relatability, understanding, and concern. Once feedback was received on those questions, participants were asked to reflect on the differences between video and text as a storytelling and localization strategy.

Participants overall found both videos and text relatable. All had some SLR-related experience to share, though not necessarily long-term concerns. Most relatability of the storytelling was through places mentioned or through daily lived experiences. Participants did not describe any significant difference in the way relatability changed or was different from video to text. One participant commented specifically on the value of videos over textual quotes:

I agree that [the videos] were all very relatable. And I feel like if I had just seen the quotes, I might have been able to relate to an extent, but the videos really made the problem real and you could like actually see their homes and see the areas that that they were referring to, and even, as someone who basically lives on top of a mountain like not in the coastal community, I still felt like I was able to empathize with the issues that they’re expressing.

This response came from the only focus group participant who did not live in the region but who was enrolled in courses virtually at the local institution.

Participants shared how they better understood a concept or approach after watching the videos and also discussed how the localization strategies might engender better understanding in others. One participant noted:

Some people are kind of stubborn, so unless they see it visually, they don’t want to believe it. Like for coronavirus, a lot of people didn’t believe that was true until they got it. And they saw a lot of people were getting it, and then they started to believe it and then get their vaccine and start protecting themselves. So, I feel like people nowadays are really stubborn and they want to believe things until they actually see with their own eyes. But for this, when they see it with their own eyes, it is going to probably be too late. So, I think if we have a historical vision of what it was like 50 years ago to now, it would be very helpful.

This participant spoke of the visual modality as being potentially influential, perhaps replacing an experiential component in aiding understanding. The “see it to believe it” approach was noted here and throughout other frames as well as a way to highlight urgency or bring people directly into the risk. Some participants implied that a sense of retroactive or historical storytelling was not effective; storytelling in the moment (e.g., live video on social media) or data for historical context seemed to be more effective.

Two participants specifically noted the power of visualization in aiding their understanding of risk. One noted that being able to identify where the water had previously risen would be more instructive than a statement about SLR, and another participant highlighted the affective component of videos as it pertains to understanding:

. . . seeing the videos would have been better because . . . I need an emotion to go along with how people feel about a certain issue to help me understand it more. And I think that would have been really, really helpful to see the video because I could see the emotion on their faces when they’re talking about it, and it would be more impactful to me.

In contrast, other participants felt that the video hindered their sense of understanding content, as potentially being “distracted by the scenery.” Others “absorb[ed] more” while reading text.

The final element of the modality frame was coded around participants’ responses to whether they felt more concerned after reading the quotes or watching the videos. This question was asked to elicit specific insights into how modality influenced their levels of concern (on a Likert scale) for SLR in the region. One participant noted specifically how watching the video changed their level of concern:

Yes, like if I wouldn’t have seen the videos, I’d probably put neutral, but because I saw the videos, I’m concerned, especially that people have to live like that, where it’s like, man . . . like I couldn’t imagine coming to my neighborhood and it being a puddle. Like I couldn’t imagine that, so yeah: I think watching the videos made me concerned, definitely.

Being unable to imagine something does hint that the videos potentially evoke SLR in a way that text does not, even though the videos did not show poor weather conditions.

Another participant noted the affective dimension in the video, noting how that linked to their concerns:

I agree—I think the videos added a very human touch to it. I feel like text, although powerful in its own way, doesn’t quite give the same emotional response as somebody who could be your neighbor, who could be your mom, who could be your best friend [. . .] I watch these videos and I know that it’s in Ghent and it’s in Hampton and it’s in Norfolk and it’s like wow, okay: now I’m actually very concerned, this is very much an issue that needs to be handled now.

Participants seemed to associate themes of imagination and humanity more closely with video storytelling than with text, and they also linked these location-visualizing aspects of the narratives to concern. Other than the preceding examples, participants gave few other details about how modality influenced their levels of concern. We suggest the website may have heightened concern, regardless of video or text, because of its overarching meta-narrative of climate change and (SLR) risk.

Usability

After reflecting on their own experiences, participants were asked how the sites could be more effective in helping people understand SLR in the region. Throughout the focus groups, participants expressed their general likes and dislikes of the site and ways it could be more engaging. Their feedback fell within the topics of effectiveness and changes to design features and was split in terms of positive (effective or designed well in some way) and negative (areas of improvement) comments.

Most of the effectiveness-related responses focused on the lengths and types of videos. One participant noted that the videos were too long, and the “news interview” feel of the videos was appropriate for an older generation but not a younger one that would expect the story to “get to the point” earlier. In that same conversation, one participant noted that they “found the quotes to be short enough to understand what they’re saying, so I don’t really have any problem with the quotes I mean they’re not like long he can read them quickly, so I don’t have a problem with that.”

Another participant spoke of demographics and the age of the storytellers, noting, “. . . even diversifying the age, that you have a [person who might say], ‘Oh that’s just the old people problem, like they’re just always old people . . . complaining, they’re just complaining about something else.’” These comments focused less on comparing effectiveness of videos versus quotes and more on improving the genre, cogency, and relevance of the stories for a younger generation.

One focus group engaged in an interesting conversation about the ethos of the recorded speakers. Three participants discussed the value of having someone from “an elite university” speaking versus a typical resident. One participant suggested speakers should include spokespeople from different groups, like a church leader or military leader, to convince those who are resistant to climate change or SLR. Their implied claim was that showing more educated speakers might be less effective, given who needs to be convinced. Two other participants resisted the educated versus uneducated dichotomy. The design feature, in this respect, was the degree to which the site should have a persuasive quality and more intentionality in who was speaking.

The only other design feedback was about how the usability of the map component would be limited to those living in the area.

Locality

Participants were asked both broadly regional and locally-specific questions about their concerns about future flooding and mitigation efforts. We shared some of the survey responses related to concerns and actions that they think they may need to take with focus group participants, and asked them to share what their survey responses had been and how they would respond now. Many participants from both the video and text groups described flooding that they had experienced, both from storms or nuisance flooding. The presentation of the website during the focus group prompted sharing additional experiences, including lighthearted daily flooding anecdotes and serious concerns for grandparents or other family members living in more vulnerable regions. Concerns about the region were diverse, including infrastructure worries and the participants’ futures living in the area. These concerns were not linked to videos versus text.

Finally, perhaps because of the younger demographic of our participants, most shared that they did not know what types of action they might take in response to SLR. They were intrigued by experiences and stories but wanted more guidance on how to act. One participant noted the usefulness of one of the video stories, which suggested ideas and mitigation measures.

DISCUSSION

One of our core questions was whether localized storytelling helps users better engage with and understand SLR and flooding risk when stories are integrated in data-centered, interactive material—the theoretical framework in our previous publication (Stephens & Richards, 2020). One underlying rhetorical assumption of our storytelling project was that localized narratives at “street level” would be most effective as videos. We wanted to test this assumption and determine if oral history and storytelling must be presented in video format or if users can be offered a similarly-effective choice between video and text. We also wanted to characterize affordances and constraints of the medium selection when attempting to localize risk. In this study, our sample size was small and participants were not selected randomly; therefore, we do not have generalizable answers to these questions. However, from our findings, we can theorize for practitioners who are interested in incorporating narrative elements into risk communication projects and we can suggest future research.

First, we find videos do not necessarily localize risk communication better than textual narratives do, except for specific circumstances. Layperson narratives of climate change often differ structurally from official scientific narratives, presenting a sequence of events and identifiable actors who have agency rather than a list of impersonal truth claims, and those narratives can more effectively connect the public to climate change (Lejano et al., 2013) Although survey results showed that the video group was slightly more concerned about SLR after viewing, the focus group discussion showed a more nuanced response from participants. Some focus group participants—particularly those who did not live in the area—said that the videos personalized SLR, suggesting that videos might help audiences visualize unfamiliar places but might not be valuable beyond text for local residents who have a visual framework. Other participants were skeptical that users would choose to watch an entire non-scripted video of people telling a story.

Second, survey results showed a slight disconnect between concern about environmental issues (like pollution and climate change) and immediate personal concern about safety due to SLR, with more participants being concerned about non-localized issues. Focus group discussions also showed that participants wanted specific suggestions for action and response. Two factors may contribute to these findings: (1) a disconnect between broader issues and localized actions, and (2) participants’ perception that they have not yet been affected by SLR. Younger participants, like college students who are a mobile population, may perceive that they can relocate in response to future flooding. In other environmental risk-related research, Sackey (2020) has emphasized the need to connect local experiences to larger-scale policy issues in order to effect meaningful change.

Storytelling in this project did not directly address policy or broader issues with which participants may have been familiar (e.g., carbon emissions). Community stories did facilitate connections between the broader risk of SLR and the everyday experiences and habits of residents in the vulnerable region. But the storytellers were not instructed to make links between the local and the global, nor to address specific actions that they had taken in response to flooding. In the survey and focus group discussions, we presumed that the juxtaposition of the SLR viewer and its open data exploration with stories would make the local–global connection explicit, but we found no evidence of this link, perhaps because of the spatial separation on the sites (stories on the left, data on the right) and because we put the “Actions you can take” page at the end of the website. Thus, our content scripting and organization may not have afforded the intended concrete connections between global risk and lived experiences.

Building on our findings, our intent in the original website design was embedded within the literature on SLR viewers as an emerging genre of web tools (Richards, 2019; Stephens et al., 2014, 2015). These viewers have meta-narratives, with users able to follow historical and projected data and personalize them for specific addresses—to see how much water it would take to inundate their property or landmark of interest. SLR Stories included a more “human” voice, which is rare in this type of tool; both oral histories of floods and data-centered tools exist, but few tools merge the two (Richards, 2019; Stephens et al., 2014). Thus, our site combined two types of localization to bring stories “home,” using Sun’s (2006) thinking about adding cultural contexts to localization technologies (e.g., SLR viewers). However, SLR Stories might provide too much information for a user without more explicit direction about how to use and interpret the data, or users may need a website that scaffolds technical information to the audience’s level of expertise (Retchless et al., 2021). Alternatively, embedding the stories directly into the SLR viewer, rather than separating content into two halves of the page, might be more effective.

Third, future research is needed to determine what features would make videos more effective as a localization strategy. For example, Lejano et al. (2018) tested a “relational model” of risk communication for typhoon warnings and found that users responded more strongly to text-message warnings that incorporated elements found in face-to-face communication (e.g., second-person voice, stories issued by specific individuals, and narratives with lay language and vivid description). Several respondents in our focus groups noted the potential of these more direct features, specifically mentioning individuals’ stories with a certain ethos or group membership. The broader “voices of the community” approach elicited story exchange and facilitated a sense of community in shared experiences among participants, but they often were confused about why these specific individuals were chosen. Clarifying why individuals were chosen to share stories might increase user engagement.

The two parts of the research—surveys and focus groups—provided more findings about engagement. The strong engagement with sharing stories in the focus groups points to the importance of the context of use in which users would be interacting with a website like SLR Stories. Participants completed surveys quickly; content included four videos of at least 3 minutes each, yet a majority of survey takers spent 20–30 seconds or less on that part of the survey, demonstrating that they did not take the time to view the entire video. As a result, comparing the levels of concern from videos versus text was challenging to measure. This challenge indicates the importance of following up to understand how viewers might interact with this website in a real-world setting; perhaps only the more motivated users would be interested in watching videos, as opposed to reading short quotes. Additionally, we suggest that a complex website like this might be more productively used in an outreach or community discussion session, in which a trained facilitator helps users explore the tool to spur dialogue on risk mitigation or adaptation.

Fourth, the focus group conversations brought home to us the importance of participatory design, with participants eager to share feedback on improving the effectiveness and usability of the sites. Our project was originally not conceived as a participatory design project (Stephens & Richards, 2020), but as an attempt to connect a large-scale issue to local concerns through place-based stories, as in the broader environmental risk communication literature (Lejano et al., 2018; Moser et al., 2016). As other TC researchers have found, participatory design is key to producing localization strategies that are truly responsive to the needs and desires of community members (Agboka, 2013; Shivers-McNair & San Diego, 2017). Both survey and focus group conversations revealed that participants had a variety of concerns, uncertainties, and misconceptions related to SLR that our community storytellers simply did not address, as well as different information types and formats that they would have wanted to see in an interactive SLR risk communication tool. We also would be interested in future research on affording users with greater options when selecting their preferred medium for engaging in SLR communication (e.g., the option to view either text or videos, or both).

Ultimately, we see from our study that voices make a difference. Our participants engaged with the stories, if only to use them as a springboard to share their own stories (the most common response and theme throughout) during the focus groups. We argue that storytelling as a localization strategy for flood risk can be effective if the storytelling is clear in its intent and intentional per who is speaking and why. The stories in our study were engaging and generative for participants, regardless of medium (video or text), so perhaps stories need not be in video form.

Additional research is needed to corroborate that videos are not the only effective method of localization when designing public-facing SLR tools and to test these tools for user effectiveness. We did not find that participants’ levels of concern differed between those who watched the videos versus reading the stories; therefore, larger-scale studies are needed to test this concept, perhaps through a pre- and post-test exposure-testing (quasi-experiment) model. Future research may also expand the participant pool, beyond student participants (who may have less home ownership experience, greater geographic mobility, and more experience with and access to technology than other members of our target audience). Additionally, we suggest more research on how best to tailor stories to help audiences connect to local and global contexts of risk and to provide actionable information that can help build user agency for SLR mitigation and response. Although technical communicators should draw on the risk communication literature for future and similar studies, the localization process also points to the importance of participatory design to help TC understand the importance of physical, cultural, and social context.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the three reviewers of this article for their careful feedback. We would also like to thank the people in this study, both those telling their stories and those participating in the research. Funding from this project came in part through ACM SIGDOC’s Career Advancement Research Grant.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Daniel P. Richards is an associate professor of English at Old Dominion University. His research has covered a variety of areas, including the politics of higher education, disaster and risk communication, and the intersections of posthuman and new materialist theory in the field of rhetoric. Most recently, his work focuses on the empirical study of visual risk communication, particularly through the lens of community engagement, to best understand how to communicate sea level rise and flooding to coastal communities. Dr. Richards can be reached at dprichar@odu.edu.

Dr. Sonia H. Stephens is an associate professor of technical communication in the Department of English at the University of Central Florida. She studies ways to convey scientific and technical information to different audiences using visual and interactive media. Her current research focuses on the user-centered development of products designed to communicate about natural hazards-related risk and mitigation information with coastal residents. Dr. Stephens can be reached at sonia.stephens@ucf.edu.

REFERENCES

Agboka, G. Y. (2013). Participatory localization: A social justice approach to navigating unenfranchised/disenfranchised cultural sites. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22(1), 28–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2013.730966

Butts, S., & Jones, M. (2021). Deep mapping for environmental communication design. Communication Design Quarterly, 9(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1145/3437000.3437001

Geisler, C., & Swarts, J. (2019). Coding streams of language: Techniques for the systematic coding of text, talk, and other verbal data. University Press of Colorado.

Hampton Roads Alliance. (2021, December 28). Maps. Hampton Roads Alliance. Retrieved July 13, 2022, from https://hamptonroadsalliance.com/maps

Herring, J., VanDyke, M. S., Cummins, R. G., & Melton, F. (2017). Communicating local climate risks online through an interactive data visualization. Environmental Communication, 11(1), 90–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2016.1176946

Lejano, R. P., Casas, E. V., Jr., Montes, R. B., & Lengwa, L. P. (2018). Weather, climate, and narrative: A relational model for democratizing risk communication. Weather, Climate, and Society, 10(3), 579–594. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-17-0050.1

Lejano, R. P., Tavares-Reager, J., & Berkes, F. (2013). Climate and narrative: Environmental knowledge in everyday life. Environmental Science and Policy, 31, 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.02.009

Lindberg, O. (2020, January 12). 6 essential tips for A/B testing UX & Design: Adobe XD ideas. XD Ideas. Retrieved July 13, 2022, from https://xd.adobe.com/ideas/process/user-testing/effective-ab-testing-essential-tips

Lune, H., & Berg, B. (2017). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Pearson, New York.

Moser, S. C. (2010). Communicating climate change: History, challenges, process and future directions. WIREs Climate Change, 1, 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.011

Moser, S. C., Daniels, C., Pike, C., & Huva, A. (2016). Here-now-us: Visualizing Sea level rise and adaptation using the OWL technology in Marin County, California. Susanne Moser Research and Consulting, Santa Cruz and Climate Access, San Francisco.

Nicholson-Cole, S. A. (2005). Representing climate change futures: A critique on the use of images for visual communication. Computers, Environment, and Urban Systems, 29, 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2004.05.002

Priestly, R. K., Heine, Z., & Milfont, T. C. (2021). Public understanding of climate change-related sea-level rise. PLOS One, 16(7), e0254348. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254348

Retchless, D. P. (2018). Understanding local sea level rise risk perceptions and the power of maps to change them: The effects of distance and doubt. Environment and Behavior. 50(5), 483–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916517709043

Retchless, D., Mobley, W., Davlasheridze, M., Atoba, K., Ross, A. D., & Highfield, W. (2021). Mapping cross-scale economic impacts of storm surge events: Considerations for design and user testing, Journal of Maps, 17(1), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2021.1940325

Richards, D. P. (2019). An ethic of constraint: Citizens, sea-level rise viewers, and the limits of agency. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 33(3), 292–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651919834983

Richards, D. P., & Stephens, S. (2021a). SLR stories [home page]. https://tinyurl.com/SLRstories-videos

Richards, D. P., & Stephens, S. (2021b). SLR stories [home page]. https://tinyurl.com/SLRstories-quotes

Sackey, D. J. (2020). One-size-fits-none: A heuristic for proactive value sensitive environmental design. Technical Communication Quarterly, 29(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2019.1634767

Schneider, B., & Walsh, L. (2019). The politics of Zoom: Problems with downscaling climate visualizations. Geography and Environment, 6(1), e00070. https://doi.org/10.1002/geo2.70

Shivers-McNair, A., & San Diego, C. (2017). Localizing communities, goals, communication, and inclusion: A collaborative approach. Technical Communication, 64(2), 97–112.

Stephens, S. H., DeLorme, D. E., & Hagen, S. C. (2014). An analysis of the narrative-building features of interactive sea level rise viewers. Science Communication, 36(6), 675–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547014550371

Stephens, S. H., DeLorme, D. E., & Hagen, S. C. (2015). Evaluating the utility and communicative effectiveness of an interactive sea-level rise view through stakeholder engagement. Journal of Business & Technical Communication, 29(3), 314–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651915573963

Stephens, S. H., & Richards, D. P. (2020). Story mapping and sea level rise: Listening to global risks at street level. Communication Design Quarterly, 8(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3375134.3375135

Sun, H. (2006) The triumph of users: Achieving cultural usability goals with user localization. Technical Communication Quarterly, 15(4), 457–481. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427625tcq1504_3

Sweet, W. V., Hamlington, B. D., Kopp, R. E., Weaver, C. P., Barnard, P. L., Bekaert, D., Brooks, W., Craghan, M., Dusek, G., Frederikse, T., Garner, G., Genz, A. S., Krasting, J. P., Larour, E., Marcy D., Marra, J. J., Obeysekera, J., Osler, M., Pendleton, M., … Zuzak, C. (2022) Global and regional sea level rise scenarios for the United States: Updated mean projections and extreme water level probabilities along US coastlines. (NOAA Technical Report NOS 01.) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Ocean Service, Silver Spring, MD, pp. 111. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/hazards/sealevelrise/noaa-nos- techrpt01-global-regional-SLR-scenarios-US.pdf