doi: https://doi.org/10.55177/tc914783

By Guiseppe Getto and Suzan Flanagan

ABSTRACT

Purpose: This article documents ongoing UX research to develop a grant-funded mobile safety app for recreational boaters. The article presents a workflow for designers to align user advocacy with organizational accountability through the use of personas. Each year, numerous boating safety concerns and incidents go unreported. User research into this context shows that recreational boaters want a mobile app that helps them enjoy boating trips while remaining safe.

Method: We reviewed best practices from literature, analyzed interviews with 141 stakeholders, and then discussed findings using personas to amplify user agency as part of a Lean UX workflow for the development of a mobile app that balances users’ goals with organizational accountability.

Results: Representative groups of boaters want features that help them with navigation, charting, and communication. These features would help alleviate pain points and enable goals having to do with not getting lost, avoiding hazards, and communicating trip progress to audiences onshore. In addition, the personas we have developed will help us communicate to the development team behind the app to explain how they can develop features that accommodate users’ needs.

Conclusion: Though personas are limited as to how well they represent actual users, if used properly within a design process they are a powerful tool for amplifying user agency so that resulting apps achieve user adoption. As part of a Lean UX workflow, personas are a useful tool in tailoring products and services to user needs while ensuring organizational accountability to those needs.

KEYWORDS: User experience (UX), Persona, User advocacy, Agency, Research method

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Successful design processes must align business goals with user goals to achieve organizational sustainability and user adoption. Design processes must consider the goals and pain points of actual users.

- UX researchers and others interested in user advocacy can use personas to amplify the impact that users have on design processes by providing developers with a means to understand user needs and to translate these needs into features.

- Though personas are limited as far as representing actual users, if used properly within a design process, they are a powerful tool for ensuring that resulting apps achieve user adoption. (We call this organizational accountability.)

INTRODUCTION

UX design has become an established sub-field within technical communication (TC), with researchers and practitioners doing everything from usability testing to developing working prototypes of apps. At the same time, both researchers and practitioners have documented a wealth of best practices for engaging in design processes that centralize users. As these practices are continually evolving as new technologies are developed, however, new practices must always be documented as design situations change. Newer technologies such as mobile apps have ushered in new challenges.

In this context, this article documents ongoing UX research to develop a grant-funded mobile safety app for recreational boaters. The article details a workflow for aligning user advocacy with organizational accountability through the use of personas. Each year, numerous boating safety concerns and incidents go unreported. User research into this context shows that recreational boaters want a mobile app that will help them enjoy boating trips while remaining safe. In order to represent the needs of recreational boaters for the developers of this mobile app, we developed a practice we call using personas to amplify user agency.

By using personas to amplify user agency, we delve into a problem that has plagued UX research since its inception: how best to incorporate user feedback into a design process. This problem has been answered many times, but no universal best practice exists. At the center of this problem is the underlying question of how much agency users should have in a design process. Though user advocacy is an important catchphrase in modern UX discourse, the question of how best to advocate for users is also still an open one. Thus, our process of using personas to amplify user agency springs from the following research questions:

- What pain points,[1] goals, and key characteristics best differentiate user groups within interview data collected on recreational boaters?

- What personas, or archetypal users, best represent these user groups?

- At a broader level: how can personas best be used to amplify user agency within a design process?

To answer these questions, we discuss user interviews with recreational boaters from across the US: to identify pain points, goals, and key characteristics amongst this group of stakeholders and to differentiate user groups into personas. These personas will be used to define requirements that the development team behind the SeaMe mobile app can meet through the development of specific features.

Currently, recreational boating accounts for a significant percentage of recreation-related accidents, property damage, and fatalities. The U.S. Coast Guard’s report in 2019 documented 4,168 accidents that involved 2,559 injuries; approximately $55 million of property damage; and 613 fatalities that resulted from recreational boating accidents (American Boating Association, n.d.). According to industry insiders, U.S. boating regulations have not been adequately updated since the 1970s because of successful lobbying by boating manufacturers (Anonymous, personal communication, February 2021).[2] From interviews for our research, we were also informed that recreational boating administrators exceed their state budgets for boating safety, meaning that additional funding is not available to increase programming that would decrease incidents.

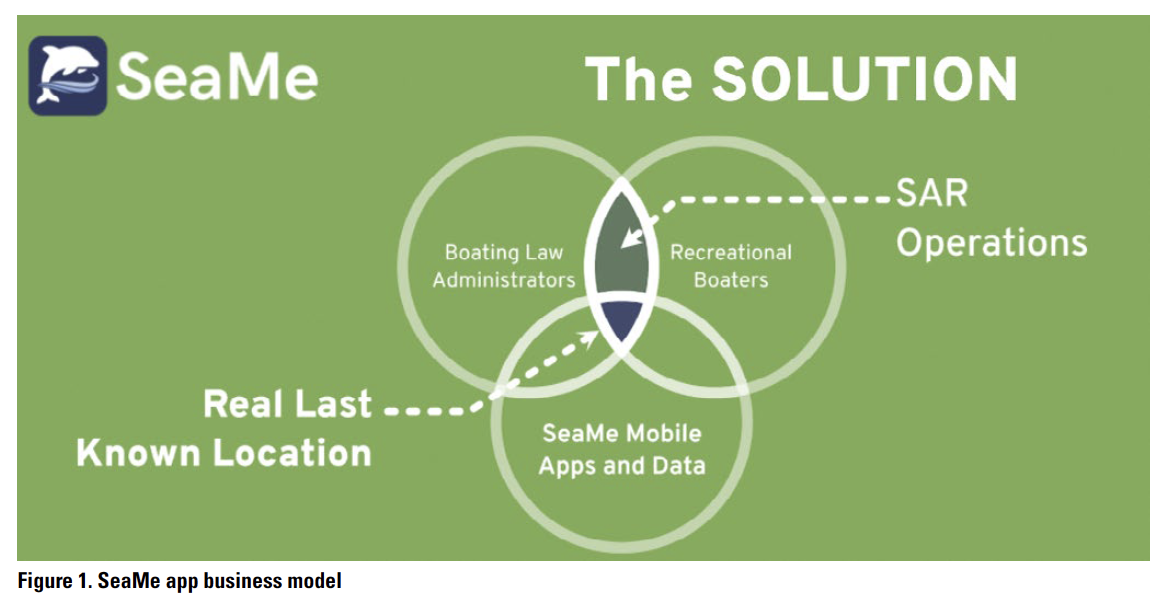

While interviewing to gather data for our research, the first author was enlisted to serve as entrepreneurial lead on an NSF I-Corps grant. In this role, he conducted interviews with potential users of a free mobile app that, if developed, might improve boater safety. The nascent business model of this app involves an exchange of a free mobile app for user data. In interviewing, he learned that government regulators who oversee recreational boating safety, including state representatives known as Boating Law Administrators (BLAs), spend large portions of their annual budgets on costly search-and-rescue (SAR) operations to track boaters who have become lost—a problem that a new app would help solve. Recreational boaters, on the other hand, want an app that helps them boat safely. The result is the SeaMe mobile app, which delivers anonymized data on boater positions to emergency responders to help them more efficiently find lost boaters. SeaMe also provides boaters a free, full-featured safety app that runs on a mobile phone (Figure 1).

The BLAs whom we interviewed are using data from past incidents to help plan for new incidents. No consistent, real-time data are currently available on recreational boating. In addition, first responders typically learn of lost boaters from a friend or family member who reports them missing, and BLAs must calculate the cost of human life based on how much they can afford to spend on each SAR incident. At the same time, recreational boaters who have smaller boats (less than 24 ft) typically lack access to advanced safety warning systems that come standard on large vessels, such as GPS-based systems that track boating traffic and underwater hazards. Thus, an opportunity exists to provide free safety features in an accessible form to recreational boaters while alleviating a major pain point of BLAs.

The BLAs whom we interviewed are using data from past incidents to help plan for new incidents. No consistent, real-time data are currently available on recreational boating. In addition, first responders typically learn of lost boaters from a friend or family member who reports them missing, and BLAs must calculate the cost of human life based on how much they can afford to spend on each SAR incident. At the same time, recreational boaters who have smaller boats (less than 24 ft) typically lack access to advanced safety warning systems that come standard on large vessels, such as GPS-based systems that track boating traffic and underwater hazards. Thus, an opportunity exists to provide free safety features in an accessible form to recreational boaters while alleviating a major pain point of BLAs.

SeaMe, a seemingly simple solution, has required extensive research and development but is not yet ready to be deployed. The process leading to this business model has involved Lean UX research and user advocacy that other researchers and practitioners can apply to their own work. In this article, we share our review of best practices from mobile UX literature and our analyses of 141 user interviews, and then we discuss using personas to amplify user agency as part of a Lean UX workflow to develop a mobile app, a process that balances user goals with what we call organizational accountability.

Below, we discuss literature that enabled us to utilize user advocacy and persona development as well as how our own approach compares. In a previous manuscript, we reported the pain points of BLAs (Getto et al., 2021); in the present article, we focus on the pain points articulated by recreational boaters. We then discuss our research methodology, using personas to amplify user agency, and we contextualize this methodology within our overall Lean UX workflow. From here, we present our finalized personas and discuss how they impact the design process going forward. We close with limitations to our approach that we discovered, and we recommend future research.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In reviewing literature for best practices, we considered work on mobile apps, Lean UX, user advocacy, and TC as well as integrating our past research into the foundation for this study.

Mobile Apps, Lean UX, and User Advocacy

The central term for the work in which UX designers engage is the UX design process—defined as the sum of activities that need to occur to ensure a high-quality user experience (Buley, 2013; Garrett, 2003; Hartson & Pyla, 2012; Hoober, 2017; Interaction Design Foundation, n.d.). This process is typically depicted as a series of stages that a UX designer (or more often, a group of designers) goes through to produce a digital product or service for a specific group of users. Digital apps are expanding at an exponential rate, so UX designers are often responsible for building products and services as diverse as enterprise software for large companies, learning management systems for institutions of higher education, mobile apps for startups, and public-facing websites for organizations. If the app is being produced according to current best practices, which is not always the case, then designers will gather information from users at several stages of the design process to ensure the app meets user needs.

The stages of the UX design process vary from practitioner to practitioner but typically involve the following steps (Buley, 2013; Garrett, 2003; Hartson & Pyla, 2012; Hoober, 2017; Interaction Design Foundation, n.d.):

- Preliminary research involves gathering user information and defining requirements.

- Prototyping is developing a working simulation of the final product or service.

- Usability testing a prototype encompasses assessing the prototype for usability with actual users.

- Maintenance has designers launching the product or service and maintaining its user experience over time on an as-needed basis.

Essentially, design projects start with user interviews, preferably in the context in which users will use the app. These interviews might be followed up with observational sessions with users during which UX researchers note common work practices, technology usage, and other elements of the users’ context. From this contextual data, a rough prototype of the app is developed. In the past, this process commonly starts with a paper prototype—sometimes still the case, according to our anecdotal interactions with practitioners—but often proceeds to a low-fidelity, clickable prototype that can be used in usability testing. This prototype is then refined through succeeding rounds of usability testing until it reaches high fidelity and finally is launched as a product or service. Maintenance of the product or service often entails updates, design tweaks, and content strategy for the product, with the design process beginning again in earnest when an exigence for major changes arises, such as changes to web standards or organizational goals.

Technical Communication and UX

Although many researchers have explored the UX process within TC literature (e.g., Albers, 2003, 2004; Andrews et al., 2012; Getto & Moore, 2017; Potts, 2009, 2013; Shivers-McNair et al., 2018; Spinuzzi, 2005; St.Amant, 2018; Sun, 2013), we found that few specifically investigated mobile UX (Getto et al., 2020; Hennes et al., 2016; Verhulsdonck, 2017) or Lean UX (Batova, 2020; Getto et al., 2016, 2021). Additionally, when looking for dedicated workflows for designing mobile apps (from start to finish of an app’s design), next to none were available within TC research.

This work is too diverse to sum up in a paragraph, but highlights include:

- UX and TC feed into one another academically and professionally, based on the paths graduates of TC programs tend to follow (Getto et al., 2013, 2016; Getto & Beecher, 2016).

- These developments require TC to develop new research methods, pedagogies, and best practices that enable us to research, teach, and do UX within our workplaces (Albers, 2003, 2004; Andrews et al., 2012; Getto & Moore, 2017; Potts, 2009, 2013; Shivers-McNair et al., 2018; Spinuzzi, 2005; St.Amant, 2018; Sun, 2013).

- These research methods, pedagogies, and best practices are distinct from those in other disciplines (i.e., computer science or IT) and show that the disciplinary foci of technical communication are influencing the way we think about UX.

In other words, the UX process involves several forms of communication (e.g., usability testing, cross-functional teamwork, communication of complex topics to non-specialist audiences) that are of interest to technical communicators, and thus a productive influence exists between the two disciplines and the fields will not be disentangled any time soon. Furthermore, this continued interplay may result in technical communication becoming one of the main disciplinary homes for UX.

Lean UX and How Our Approach Differs

Our approach to Lean UX (documented in Getto et al., 2021) differs somewhat from Gothelf and Seiden (2013), who define Lean UX process as consisting of the following stages: concept, prototype, validate internally, test externally, learn from user behavior, and iterate. From Lean UX, we primarily pull this emphasis on iteration. Iteration is especially important in a mobile context because more users and types of users exist than ever before and are using apps in new ways that were not envisioned by designers. From our past literature review in this area, our working definition of mobile UX is “the processes and components of a mobile app and its users that influence, and are influenced by, individual, technological, and social factors” (Getto et al., 2020, p. 116). Combining Lean UX and our research into mobile UX best practices, we developed the following approach near the beginning of the current research project (directly quoted from Getto et al., 2021):

- Discover: Mobile UX must start with a deep dive into the core goals and pain points of real, live users.

- Advocate: Organizational goals must then be balanced with user goals so that the two become aligned.

- Account: Specific design goals must be developed that ensure organizational accountability to user goals.

- Prototype: Because mobile experiences are all so different and are focused on select groups of users, early prototypes help align user goals and pain points with affordances.

- Test: These affordances should then be tested as prospective features by providing a series of simple actions that test users can take via the prototype app.

- Refine: This entire process must be iterated until the application is a valid expression of user goals and organizational accountability systems. (p. 119)

This is our overall approach to the UX process (which we detail thoroughly in Getto et al., 2021). In the current article, we wish to explore one aspect of this process: the use of personas to amplify user agency, which largely happens at the discover, advocate, and account stages. Below we explore past literature on persona development in-depth.

Persona Development and What It Means for User Agency

Regardless of the specific context and workflows used in a UX process, the process itself largely still involves the steps articulated above: preliminary research, prototyping, usability testing of a prototype, and maintenance. As anyone who has actually enacted this process can attest, however, what may seem like a linear process on paper is often anything but straightforward. Organizational goals surrounding a given app can shift and change. Target users for the app sometimes shift, either because changes to organizational goals require it or because initial testing reveals the app is not appropriate for its original target user community. Exigences such as these mean that UX researchers “cannot consistently predict what kinds of information might be important to specific groups and in specific situations; we need methods by which we can understand the dynamic relationships between users and technologies” (Potts, 2009, p. 285). In other words, as digital products and services become increasingly pervasive and complex, the relationships among users, apps, and contexts of use become increasingly complex and unpredictable. Despite this increase in the pervasiveness, complexity, and unpredictability of use cases for digital apps, or perhaps because of it, “most users are involved in the design process too late to influence the final product” (Andrews et al., 2012, p. 124). This failure to account for users and their contexts “explains systems which function technically but fail because of lack of user acceptance” (Albers, 2003, p. 270).

As a result, mobile and Lean UX literature tends to focus on how researchers and practitioners gather feedback from target users and bridge the gap between user goals and organizational goals. Revisiting our definition of mobile UX, we can consider to “individual factors” and “social factors” that surround the design of any mobile app, and we can consider how to advocate further for target user groups from an organizational standpoint. The most influential research that investigates user advocacy in TC builds from the concept of researchers working closely with a community of users to identify core values and needs rooted within existing social relationships and processes (Grabill, 2007; Hennes et al., 2016; Potts, 2013; Sun, 2013). This deep interaction is a heuristic in itself; working with users to understand their needs and expectations should change a designer’s perspective and the organizational goals behind the app.

Building an app around existing user relationships, values, and needs is no simple task. On one end of the spectrum of methods, participatory design (Spinuzzi, 2005) incites UX researchers to involve users in actual design processes. On the other end of this spectrum are more traditional methods, like contextual inquiry (Potts & Bartocci, 2009), usability testing (Nielsen, 2012), and persona development (Getto & St.Amant, 2014). The difference is in whether users are continually or repeatedly involved in a design process or are involved only at specific moments. In a UX design process that is not explicitly based in participatory design, users are typically involved at the beginning, through contextual inquiry into their contexts of use, and when usability testing a prototype. Our goal is not to advocate for or against participatory design but to point out that in many situations it is not practical, such as when users do not have time or interest to join lengthy design processes. Such is the case in our own design process where we are attempting to develop a mobile user experience for a host of different user groups, many who are geographically dispersed. It would be very costly and time-consuming to organize those users into review groups to look at each prototype of our design.

In this way, we are where many UX researchers find themselves: project constraints leave us with distinct moments of interaction with actual users. In this case, researchers must attempt to represent how users probably will react to a design, based on careful analysis of empirical observations and interviews with real users. UX researchers take on a balancing act to differentiate users into groups so that various users’ mental models, or expectations for how a design will function, are respected. As Albers (2009) describes this process:

[Because] each user is different, user analysis which aims to construct only one representation runs a high risk of being minimally applicable to a substantial number of users. . . . Instead, the design can be based on a more general understanding of the structures of effective mental model processes which are used. An end goal of the user analysis is to define structural descriptions of possible and effective mental models. (p. 184)

The goal of delving into user contexts is to define the ways different users will react to a design, based on their mental models.

One common way that UX designers represent user reactions in this way is by developing personas or archetypal users. Persona development is a process by which UX designers seek to represent key trends in user research through crafting archetypal users that represent these trends:

A persona is a way to model, summarize and communicate research about people who have been observed or researched in some way. A persona is depicted as a specific person but is not a real individual; rather, it is synthesized from observations of many people. Each persona represents a significant portion of people in the real world and enables the designer to focus on a manageable and memorable cast of characters, instead of focusing on thousands of individuals. Personas aid designers to create different designs for different kinds of people and to design for a specific somebody, rather than a generic everybody. (Goltz, 2014)

Personas help UX researchers represent the distinct user groups of an app as a “manageable and memorable cast of characters” (Goltz, 2014) with distinct mental models, rather than a list of user requirements, numbers, and statistics.

In our own context, our perspective on our design was altered as we talked to boaters who might serve as users for a mobile app and to BLAs who might use the app to find lost boaters and also to keep boaters safe. Users, technologies, and organizational stakeholders—in this case, boaters, BLAs, organizations, and other groups—do not exist in a vacuum but are co-determiners of a design situation. All stakeholders and their needs and expectations need to be balanced to create a successful product. Stakeholders are intertwined: user advocacy will fail if organizational goals are not considered, and organizations will fail to achieve their goals if users’ goals are not met.

In the method section, we explore this balancing act further by diving into the actual research project that gave birth to this workflow. Our unit of study (Merriam, 1998, p. 27; Stake, 2000, p. 436) during the analysis of a potential user base for a mobile boating safety app was the personas representing different recreational boater users we interviewed.

METHOD: USING PERSONAS TO AMPLIFY USER AGENCY

By using personas to amplify user agency, we are thus responding to several challenges (i.e., research gaps) currently present in UX design literature:

- The question of how, and when, to involve users in a design process

- The question of how to represent users when making design decisions

- The question of how to balance user goals and organizational goals.

As we detailed above in our literature review, there are several answers to these questions, but as we mentioned in our introduction, design situations are constantly evolving. Less an entirely novel approach, then, our approach to using personas to amplify user agency is a response to several exigences from our design situation.

These exigencies include:

- Users (i.e., recreational boaters) that are scattered all over the country and difficult to reach for interactions like interviews outside of personal networks

- A large body of users with a large variety of goals and pain points

- A developing business organization behind the SeaMe app with developing goals that we are attempting to sync with user goals

- An overall mission to help intervene in a pressing social need for better recreational boating safety technology.

Our approach to using personas to amplify user agency is thus a response to these specific challenges but at the same time a response to an ongoing conversation in UX. It is certainly not a definitive approach, but we feel that it might also be of use to other researchers and practitioners in other design situations. To give context on how specifically applied the approach in our own situation, below we detail our data collection, data analysis, and findings.

Data Collection

The first author of this article was initially recruited to serve as a UX researcher on an IRB-approved study to evaluate the viability of a mobile app for recreational boaters. That initial project would expand into a multi-year one which included an NSF I-Corps grant to study the viability of such an app for users. For the purposes of the current article, between January 21 and March 5, 2021, 117 recreational boaters and 24 BLAs from across the US were recruited and interviewed. Recruitment was mostly initiated through the personal network of one of the mobile app developers, who had extensive experience in recreational boating and many recreational boating contacts. He developed a list of boaters and BLAs across the US who were contacted through email or phone for recruiting them to the project. For the purposes of this article, we focus on the data we collected on recreational boaters, having detailed our analysis of data on BLAs in Getto et al. (2021).

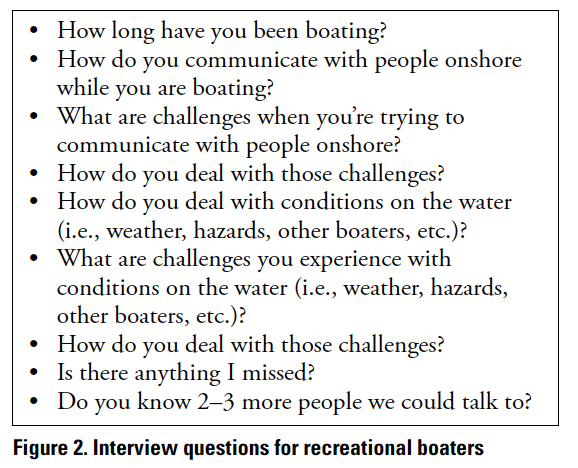

Interviews with recreational boaters were conducted using the interview questions outlined in Figure 2. Boaters were interviewed in a semi-structured format in person, via phone, or over video conference, depending on the participants’ technological aptitude and availability. After we recruited initial participants from our personal networks, we used a snowball methodology to recruit other participants.

- How long have you been boating?

- How do you communicate with people onshore while you are boating?

- What are challenges when you’re trying to communicate with people onshore?

- How do you deal with those challenges?

- How do you deal with conditions on the water (i.e., weather, hazards, other boaters, etc.)?

- What are challenges you experience with conditions on the water (i.e., weather, hazards, other boaters, etc.)?

- How do you deal with those challenges?

- Is there anything I missed?

- Do you know 2–3 more people we could talk to?

Figure 2. Interview questions for recreational boaters

We should also note that attempts to recruit participants outside of personal networks failed. At one point, for instance, we advertised the study via an email listserv to approximately 27,000 individuals and received zero responses. Members of the SeaMe app development team explained this problem as one of insularity: recreational boaters are most likely to talk to someone else interested in recreational boating. We were thus much more successful utilizing a snowball approach.

Data Analysis

The transcribed recreational boater interviews were entered into NVivo 12 Plus and, using grounded theory, coded to identify the participants’ pain points (see Getto et al., 2021 for details on coding). In the initial analysis, demographic data (e.g., age, gender, boat size) and several behavioral characteristics (i.e., involvement in a boating accident, use of float plans, and use of mobile apps for boating purposes) were entered as case attributes. However, additional data points and analyses were needed to identify and develop representative personas. More details were extracted from the interviews and entered as supplementary case attributes (e.g., boating location, boat type, safety certification).

All case attributes were then exported to Excel because some analyses were difficult to perform or to visualize in NVivo when the number of participants exceeded 50; this study involved more than 100 participants. The participant data could easily be sorted and filtered by case attributes in Excel.

We created the personas using a method similar to Quesenbery’s (2003) approach (i.e., identifying similarities in personal characteristics, tasks, and stories). Based on what we learned from the qualitative coding of participants’ problems (Getto et al., 2021), we looked for data convergence points. We hypothesized that the data would break along lines of problems related to boating types (i.e., powerboats, sailboats, or paddlecraft); locations (i.e., inland or coastal); or activities (e.g., fishing, hunting, sailing, paddling, cruising). We also looked for patterns in the data associated with boating experience, gender, or age. Participants were excluded from this analysis if their ages were unknown or if they did not use apps for boating.

The mode was determined for each case attribute. Intersections of these modes were used to identify the personas. Next, we ran a cluster analysis in NVivo to confirm that the groups of potential personas were indeed distinct from one another (Qualtrics, 2022). The cluster analysis evaluated the similarity between attribute values. We then looked for one representative participant in each cluster to serve as the inspiration for the persona (Quesenbery, 2003).

In theory, we could have started with the cluster analysis and selected a participant from each of the 10 clusters within the dendrogram; however, in practice, the Jaccard’s coefficient, which measures the degree of similarity between attributes, cannot alone reveal the distinct differences between participants nor can it accurately represent the participants’ stories (Whorton, 2021). Our mixed-analysis approach enabled us to identify five personas that would best inform the design of a mobile boating app.

FINDINGS

Findings are organized per the three research questions that this project addressed.

Research Question 1: What pain points, goals, and key characteristics best differentiate user groups within interview data collected on recreational boaters?

Pain points among recreation boaters emerged under a variety of themes (Getto et al., 2021), which included:

- Communication: e.g., the ability to communicate with people on shore, with other boaters, and with emergency responders

- Facilities: e.g., the location of marinas, boat ramps, and other amenities

- Hazards (other than other boaters): e.g., reefs, sandbars, and narrow channels

- Navigation and location concerns: e.g., the ability to track progress on a trip, the ability to navigate to a specific point, and the ability to backtrack if lost

- Other boaters: e.g., the ability to track the location of other boaters, the ability to avoid unsafe boaters, and the ability to be warned of oncoming vessels

- Safety concerns: e.g., the ability to check off required safety provisions, the ability to receive warnings regarding unsafe conditions, and the ability to be informed as to local laws and regulations

- Technology: e.g., the ability to maintain a consistent connection to GPS, the ability to use their mobile device on the water, and the ability to connect with other boaters while on the water.

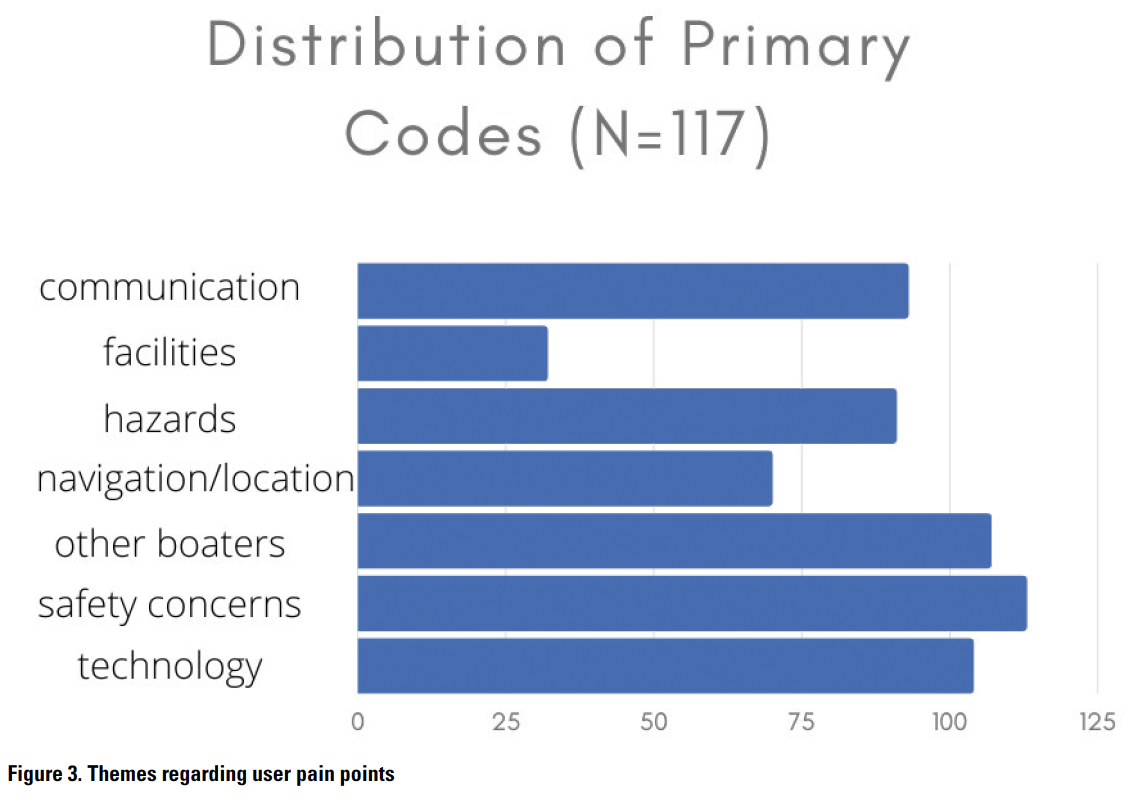

As seen in Figure 3, users expressed various concerns related to recreational boating; their concerns ranged from communicating with other parties, including their family and friends who are ashore to dealing with other boaters.

These interviews revealed that the design of this relatively simple mobile app was anything but simple. Rather, this situation contains a wide variety of pain points for recreational boaters that many different users across that group prioritize in their interviews. In this case, designing an app to meet all these needs is not possible, especially not in a mobile interface, given the strict need for simplicity and usability articulated above. Rather, crafting these data into personas, archetypal users who can serve as “a manageable and memorable cast of characters” (Goltz, 2014), has become an essential step in our design process. This step ensures that as the app is prototyped (a process the development team behind the app is currently engaged in), we can bring this prototype in line with the needs of distinct groups of users. This process for prototyping will help us with balancing user advocacy and organizational accountability, which are the hallmark of our workflow.

These interviews revealed that the design of this relatively simple mobile app was anything but simple. Rather, this situation contains a wide variety of pain points for recreational boaters that many different users across that group prioritize in their interviews. In this case, designing an app to meet all these needs is not possible, especially not in a mobile interface, given the strict need for simplicity and usability articulated above. Rather, crafting these data into personas, archetypal users who can serve as “a manageable and memorable cast of characters” (Goltz, 2014), has become an essential step in our design process. This step ensures that as the app is prototyped (a process the development team behind the app is currently engaged in), we can bring this prototype in line with the needs of distinct groups of users. This process for prototyping will help us with balancing user advocacy and organizational accountability, which are the hallmark of our workflow.

Research Question 2: What personas, or archetypal users, best represent these user groups?

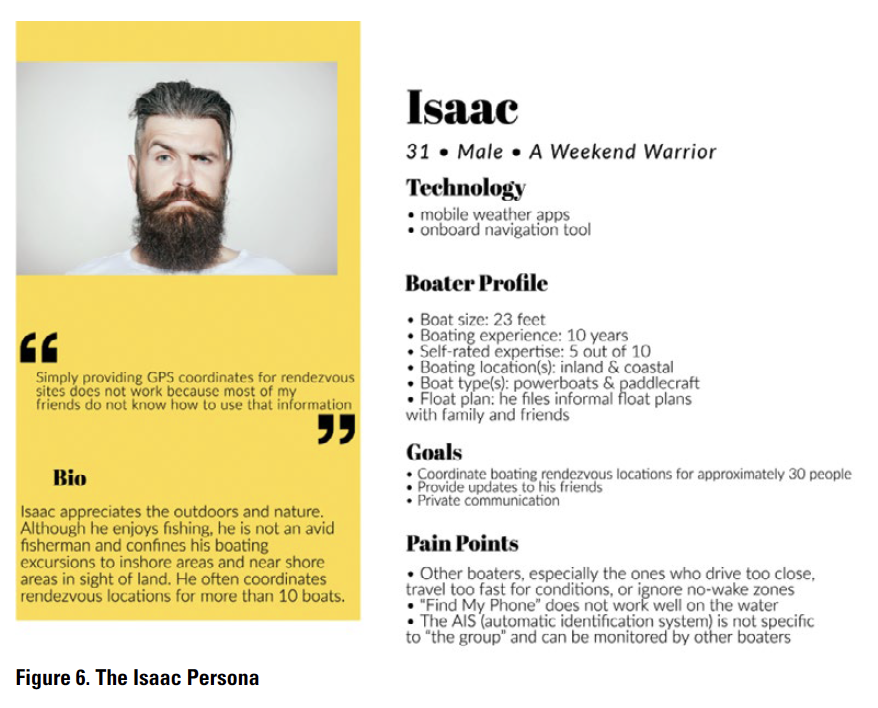

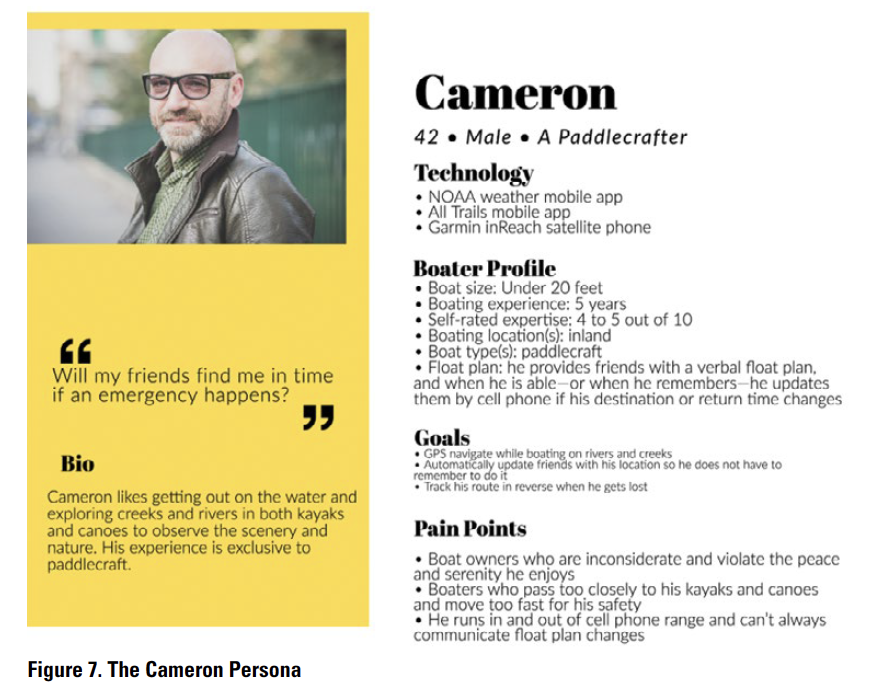

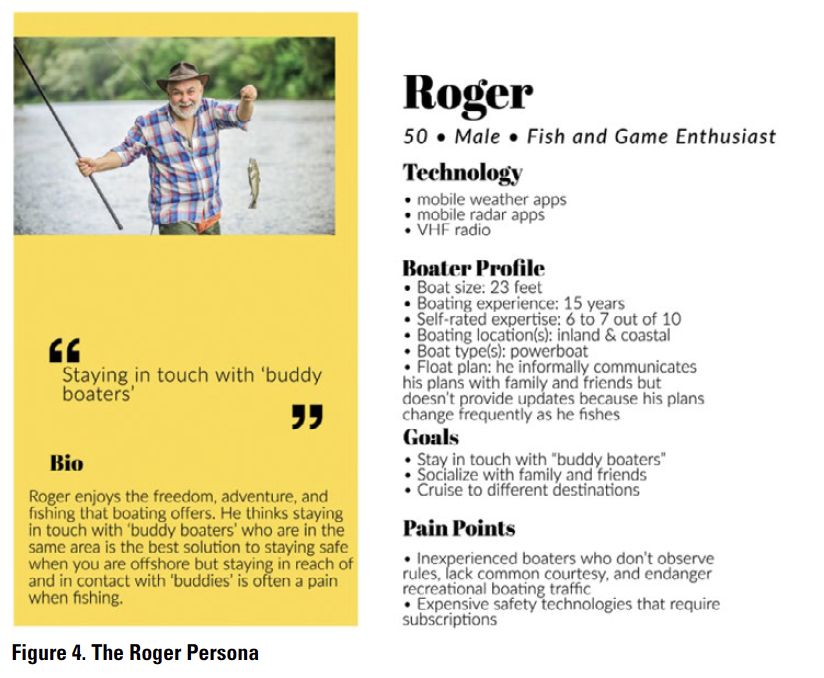

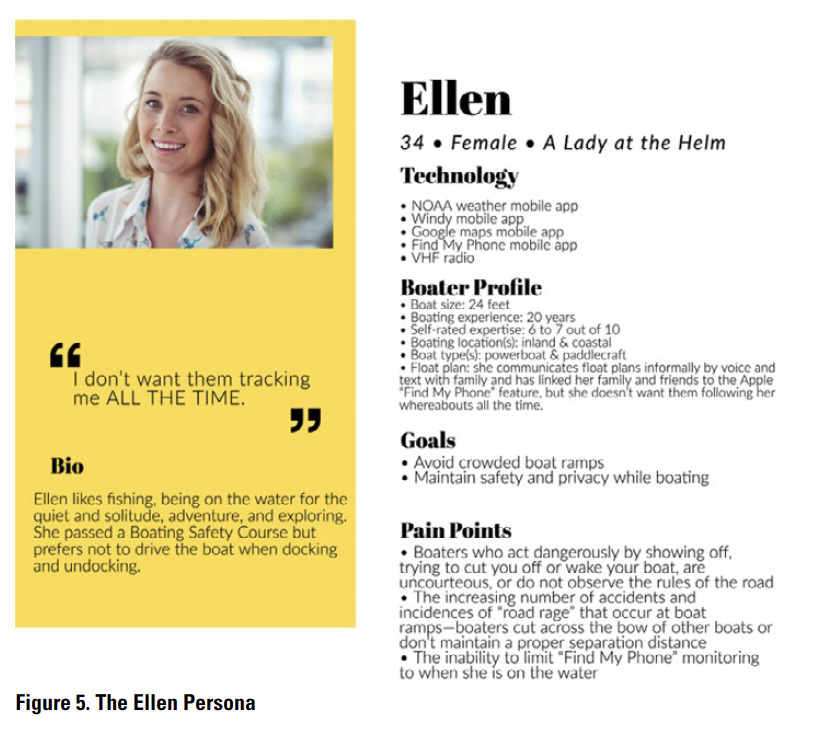

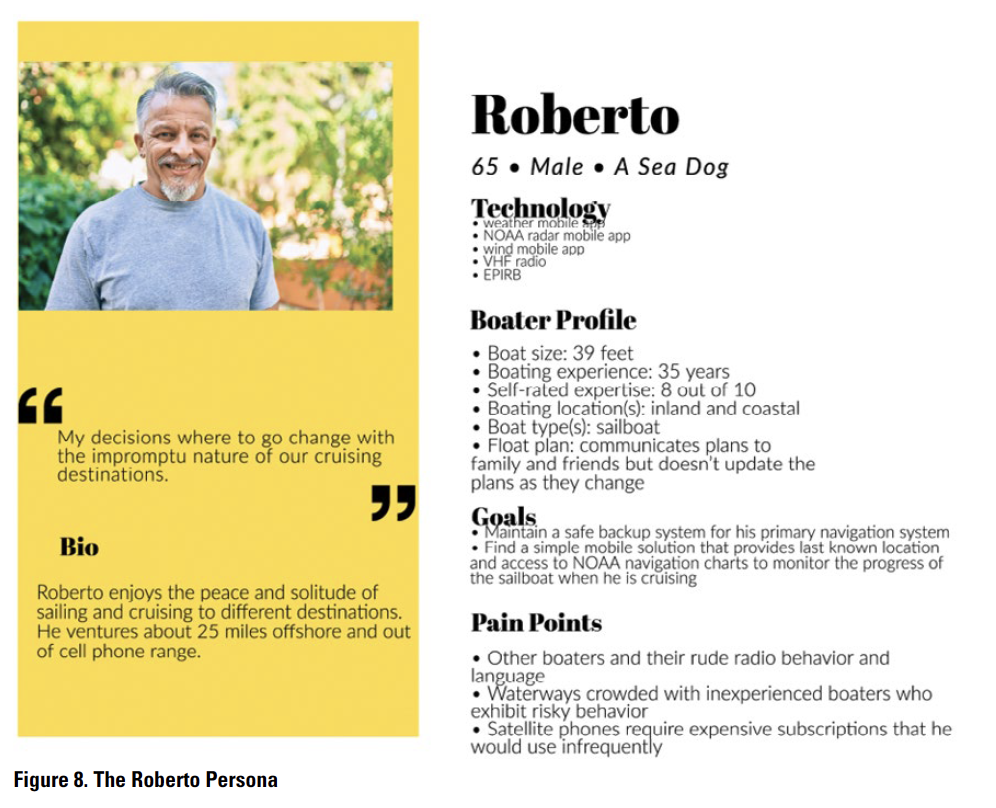

From our data analysis, we derived five personas: Roger, a fish and game enthusiast (Figure 4); Ellen, a lady at the helm (Figure 5); Isaac, a weekend warrior (Figure 6); Cameron, a paddlecrafter (Figure 7); and Roberto, a sea dog (Figure 8). The personas range in age from early 30s to mid-60s and have 5–35 years of boating experience.

(All names on personas are pseudonyms used to protect participant identities. All images are royalty-free stock images. For further details on the elements common to personas, see Getto and St.Amant, 2014.)

Most of the personas operate 20- to 30-ft powerboats. At the extremes are Cameron, a paddlecrafter who owns a boat less than 20 ft, and Roberto, a sea dog with a 39-ft sailboat. Cameron operates his boat exclusively in inland waters, and the others navigate in both inland and coastal waters. Their recreation makes sense in the context of recreational boaters, as many powerboats larger than these include reliable GPS systems that would replace the need for a mobile app. Sailboats vary as to what technology they include.

Gender differentiates one persona from the others. Approximately 20% of the study participants are female, and that proportion is reflected by the one female persona (Figure 5), though not intentionally (merely how the data aligned.) Ellen, a lady at the helm, represents those female voices that, according to one participant, are underrepresented in boating.

A primary difference that distinguishes the personas is how they boat (e.g., sailing versus paddling). Although all boaters share similar safety concerns (e.g., drowning, underwater hazards, weather), some concerns are specific to the type of boat used. For example, people who sail are largely reliant on winds, whereas those who kayak rely on muscle power and paddles to propel their crafts. Those in sailboats and paddlecraft face more difficulties to quickly navigate out of the path of an oncoming vessel or to avoid floating debris, whereas the limiting factor for those in powerboats is fuel and mechanical performance.

Another difference between personas is their purpose for boating (e.g., hunting, socializing, exploring, basking). Although these activities are not mutually exclusive or, for that matter, limited to any one boater, the main purpose of the boating excursion often corresponds to potential marine perils or communication challenges. For instance, a boater whose objective is either fishing or hunting tends to follow the fish or game, and might find themselves in unfamiliar waters or become hyper focused on their task and lose awareness of their surroundings.

Each persona speaks to a different concern or problem. Roger, a fish and game enthusiast, struggles to maintain contact with his buddy boaters (see Figure 4). Ellen, a lady at the helm, does not want to be tracked unless she is on the water (see Figure 5). Isaac, a weekend warrior, needs an easier way to coordinate meetups with other boaters (see Figure 6). Cameron, a paddlecrafter, needs a reliable method for backtracking his route (see Figure 7). Roberto, a sea dog, wants an automated, carefree method for tracking his location as he sails to impromptu locations (see Figure 8).

Research Question 3: At a broader level—how can personas best be used to amplify user agency within a design process?

Research Question 3: At a broader level—how can personas best be used to amplify user agency within a design process?

Once personas are developed, the question becomes, “how will personas be mobilized to improve the design of our prototype mobile app?” This is a complex question that deserves its own article, but simply put, personas are used by UX researchers to align the design of apps with user needs. For example, the various pain points we uncovered in our interview data at a broad level (Figure 3) are difficult exigencies for designers. UX researchers and designers must ask questions, including what requirements they should include in an app if users express safety concerns, issues with technology, or concerns with the behavior of other boaters. These broad trends are important to keep in mind but are not strong heuristics for guiding the design of an app.

Personas, however, help UX researchers “design for a specific somebody, rather than a generic everybody” (Goltz, 2014). The key is that personas must be representative of broader trends in user data. Otherwise, the specific boater for whom a design is created will not align with the group of users the persona represents. In this way, personas become a key representation of user agency and organizational accountability. UX researchers can imagine the kinds of requirements that Roger, Ellen, Isaac, Cameron, and Roberto have for a mobile app. They can envision the flows that users like these would take through an app’s features. Most importantly, the researchers can easily recruit users like these personas for usability testing once features are developed.

Moreso, UX researchers can imagine what these users can provide to the business organization behind the SeaMe app. According to that organization, its current business model involves the exchange of a free mobile app for user data. Organizational accountability in our current project means providing a fully featured mobile safety app to boaters in exchange for anonymized data that will help first responders find lost boaters faster. The organization is accountable to its users if it provides features that its users want, in this case, for free. This accountability must be balanced with providing something that furthers organizational goals—in this case the leveraging of anonymized user data to improve SAR operations for BLAs who are willing to pay for the use of this data.

Personas help UX researchers design app features that meet the needs of specific groups of users, help guide the crafting of user flows that would fit within users’ actual lives—that is, beyond the rich, micro-level details that make a group of users unique (beyond Figure 2). For example, in this case, each group of users is already using various technologies when they are boating, but for the UX researcher, it is more important to understand why they are using these technologies, what specific pain points they are trying to solve in their daily lives, and what goals users are trying to achieve.

An important goal, not only for these users but also for the incipient business organization behind the SeaMe app, is safety. One of the primary mechanisms that first responders use to locate a lost boater is a “float plan.” Similar to a flight plan that is filed before flying a plane, a float plan notifies authorities where a boater plans to go and what general route the boater plans to take. The float plan is a form of official government documentation that guides first responders in the case of an emergency (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2016). However, as readers may note, none of the user groups in the personas regularly file this documentation. Therefore, first responders are left to call emergency contacts on fishing licenses and other forms of documentation. Based on reports of boating administrators, most of the time, they are not aware that a boater is missing until a friend or family member reports concern.

At the same time, our personas do communicate informal float plans to friends and family. Thus, a feature that might be successful in our incipient app is a float plan that informs both groups: boater friends and family and first responders. Another innovation would be regular updates to the float plan so that as plans change audiences know when boaters deviate from their original plans. These features, which are not currently available in other apps, could potentially save boating administrators millions of dollars by decreasing the number of wide area searches they currently complete for lost boaters.

To effectively advocate for users, UX researchers need to pay attention to their specific goals and pain points. As mentioned above, an app that meets business goals but fails to meet user goals risks failing to attract users. In our project, it is unclear if a mobile app that only provided a float-plan feature would attract a significant user base, especially considering the goals and pain points of specific personas; none of the personas mentioned filing a float plan as a specific goal or pain point. Instead, their goals and pain points aligned at the intersection of navigation, charting, and communication. The personas’ responses indicate that our mobile app needs to provide features that enable these goals and alleviate these pain points if we expect users to adopt the app.

Data were not collected on how often user goals conflict or do not align with business goals, but our anecdotal experience as UX researchers and verbal reports of best practices from practitioners in this space indicate that misalignment is common.[3] We have witnessed apps that were launched with the best of intentions but failed to attract a user base because the apps did not attend to specific user needs and pain points. In this way, personas stand to significantly amplify user agency in a variety of design situations in which participatory design is not feasible. Personas can act as actors within design networks in which UX researchers work with app developers to develop technologies that are truly useful to users. However, personas can act within design networks only if those networks are developed and used within the specific networks of people and technologies that produce apps.

CONCLUSION: PERSONAS CAN ONLY AMPLIFY USER AGENCY IF APPLIED PROPERLY

One limitation of our current analysis, and a limitation of personas in general, is that they seek to represent actual people. In treating personas as actors within design networks, UX researchers move actual design decisions one remove from actual users. However, in many circumstances, a more participatory approach is not feasible. First, participatory design is not immune to issues of representation; UX researchers cannot run every design decision by every intended user unless the app in development is only going to be used by a small group. In the case of the SeaMe app, in the US, approximately 12 million potential users have registered boats and approximately 100 million recreational boaters are potential users (Statistics, 2021; General NMMA News, 2019). UX researchers could not vet each design decision with that many users.

As a result, participatory designers typically select representative users to participate in design activities, so they are also dealing with issues of representation (Elizarova & Dowd, 2017). In selecting representatives, our response is to tie personas to actual trends in user data. Like representative users recruited for a participatory design review, personas should be representative of actual groups of users, meaning users with similar demographics, goals, and pain points. Representation in personas does not guarantee that the resulting app will better represent users, but it makes accuracy more likely.

Another limitation of our findings is that personas can be improperly applied within design networks, such as when the utility of personas are not communicated adequately to the developers who are working on an app (Salazar, 2018). In this case, developers may fall back on technical requirements and end up with an app that does not appeal to specific users. This limitation, in our experience, can be mitigated only through the active efforts of a UX researcher who engages in a design situation. UX researchers must see an app development process through to its conclusion. Researchers no longer simply deliver their findings and walk away from the design process. Instead, UX researchers must guide this process from start to finish so that it aligns with the needs of users.

Regardless of these limitations, we are confident of these findings; our sample size was large enough to produce reliable results and the saturation of codes from interviews with participants were consistent. In future research and development, we will enter the Prototype, Test, and Refine loop common to Lean UX; in this loop, we develop and test actual app designs with users that match our initial interviews and continue to consider our personas. This loop will continue to inform us about how to balance advocacy and accountability within the context of increasing safety for recreational boaters. These personas have given us a target for this balancing point, which again centers around providing communication, wayfinding, and other safety features to users for free in exchange for anonymized data that that will assist first responders. Lessons learned during this next phase will also create additional findings for the TC community that we hope will be useful.

As for the findings of this article, we are certain of one thing: the personas we developed tell us more about the specific needs of users than any other deliverable we have created, including early prototypes that one of the authors helped to develop at the beginning of the project. These personas stand to provide a necessary method for amplifying the needs of actual recreational boaters so that the resulting app takes them fully into account. The lesson for other UX researchers and technical communicators interested in user advocacy is that personas can be a powerful tool for amplifying user agency by providing a means of communicating user goals and paint points in an understandable, persuasive manner.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by an NSF I Corps Grant.

[1] Pain points are a term of art used by modern UX designers to indicate a point during which users get frustrated, fatigued, inconvenienced, or otherwise have an aversive experience when navigating an app. The term is also sometimes applied to daily struggles they may experience that an app could solve, such as not being able to detect underwater hazards until their boat runs aground.

[2] Though a systematic review of governmental regulations was beyond the scope of this research study, this claim was supported by most of the BLAs whom we interviewed, in addition to several members of the federal government charged with administering recreational boating regulations.

[3] All the UX research we have personally reviewed has been from the viewpoint of documenting user goals and pain points and how to align the design of an app with these. There have been no studies, to our knowledge, that measure the alignment of organizational goals with user goals. Anecdotally, however, we have spoken to several dozen UX practitioners who have reported that this is a common issue.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Guiseppe Getto is an associate professor of technical communication at Mercer University and is president and founder of Content Garden, Inc. a UX and content strategy consulting firm: http://contengarden.org. His research focuses on utilizing user experience (UX) design, content strategy, and other participatory research methods to help people improve their communities and organizations. He has published a co-edited collection, Content Strategy in Technical Communication, with Routledge. The findings of his research have been published in peer-reviewed journals such as IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication; Technical Communication; Computers and Composition; Rhetoric, Professional Communication, and Globalization; Communication Design Quarterly; and Reflections; as well as conference proceedings for the Association for Computing Machinery’s Special Interest Group on Design of Communication (ACM SIGDOC). His work has also appeared in industry-based publications such as Intercom and Boxes and Arrows. He has taught at the college level for nearly twenty years and has consulted and formed research and service-learning partnerships with many nonprofits and businesses, from technical writing firms to homeless shelters to startups. He is also a poet. His first book, Familiar History, is currently available from Finishing Line Press: http://guiseppegetto.com/poetry/. Read more about him at: http://guiseppegetto.com. Dr. Getto can be reached at getto_ga@mercer.edu.

Dr. Suzan Flanagan is an assistant professor at Utah Valley University, where she teaches technical communication, editing, and collaborative communication. Her research focuses on technical and professional communication at the intersections of editorial processes, content strategy, and user experience (UX). She co-edited Editing in the Modern Classroom (Routledge, 2019). Dr. Flanagan can be reached at sflanagan@uvu.edu.

REFERENCES

Albers, M. (2003). Multidimensional audience analysis for dynamic information. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 33(3), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.2190/6KJN-95QV-JMD3-E5EE

Albers, M. (2004). Communication of complex information: User goals and information needs for dynamic web information. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410611543

Albers, M. (2009). Design for effective support of user intentions in information-rich interactions. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 39(2), 177–194.

American Boating Association. (n.d.). Boating fatality facts. https://americanboating.org/boating_fatality.asp

Andrews, C., Burleson, D., Dunks, K., Elmore, K., Lambert, C. S., Oppegaard, B., Pohland, E. E., Saad, D., Scharer, J. S., Wery, R. L., Wesley, M., & Zobel, G. (2012). A new method in user-centered design: Collaborative prototype design process (CPDP). Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 42(2), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.2190/TW.42.2.c

Batova, T. (2020). An approach for incorporating community-engaged learning in intensive online classes: Sustainability and lean user experience. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(4), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2020.1860257

Buley, L. (2013). The user experience team of one: A research and design survival guide. Rosenfeld Media.

Elizarova, O., & Dowd, K. (2017, December 14). Participatory design in practice. UX Magazine. https://uxmag.com/articles/participatory-design-in-practice

Garrett, J. (2003). The elements of user experience: User-centered design for the web. New Riders.

General NMMA News. (2019, January 10). US recreational boating industry sees seventh consecutive year of growth in 2018, expects additional increase in 2019. National Marine Manufacturers Association. https://www.nmma.org/press/article/22428

Getto, G., & Beecher, F. (2016). Toward a model of UX education: Training UX designers within the academy. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59(2), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2016.2561139

Getto, G., Flanagan, S., & Labriola, J. (2021). Designing boater advocacy: A Lean UX mobile app project to increase emergency response accountability. Proceedings of the 39th ACM International Conference on Design of Communication (pp. 118–127). https://doi.org/10.1145/3472714.3473631

Getto, G., Labriola, J., & Flanagan, S. (2020). The state of mobile UX: Best practices from industry and academia. 2020 IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (pp. 115–122). https://doi.org/10.1109/ProComm48883.2020.00024

Getto, G., & Moore, C. (2017). Mapping personas: Designing UX relationships for an online coastal atlas. Computers and Composition, 43, 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2016.11.008

Getto, G., Potts, L., Salvo, M., & Gossett, K. (2013). Teaching UX: Designing programs to train the next generation of UX experts. Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Design of Communication (pp. 65–70). https://doi.org/10.1145/2507065.2507082

Getto, G., & St.Amant, K. (2014). Designing globally, working locally: Using personas to develop online communication products for international users. Communication Design Quarterly, 3(1), 24–46. https://doi.org/10.1145/2721882.2721886

Getto, G., Thompson, R., & Saggi, K. (2016). Spurring UX innovation in academia through lean research and teaching. 2016 IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (pp. 1–9). https://doi.org/10.1109/IPCC.2016.7740527

Goltz, S. (2014). A closer look at personas: What they are and how they work (part 1). Smashing Magazine. http://www.smashingmagazine.com/2014/08/06/a-closer-look-at-personas-part-1

Gothelf, J., & Seiden, J. (2013). Lean UX: Applying lean principles to improve user experience. O’Reilly Media.

Grabill, J. T. (2007). Writing community change: Designing technologies for citizen action. Hampton Press.

Hartson, R., & Pyla, P. (2012). The UX book: Process and guidelines for ensuring a quality user experience. Morgan Kaufmann.

Hennes, J., Wiley, K., & Anderson, B. (2016). The trail reporter mobile application: Methods for UX research and communication design as civic agency. SIGDOC ‘16: Proceedings of the 34th ACM International Conference on the Design of Communication (pp. 1–5). https://doi.org/10.1145/2987592.2987620

Hoober, S. (2017, March 6). Design for fingers, touch, and people, Part 1 [Web log]. UXmatters. https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2017/03/design-for-fingers-touch-and-people-part-1.php

Interaction Design Foundation. (n.d.). What is user experience (UX) design? Interaction-Design.org. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/ux-design

Merriam, S. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass.

Nielsen, J. (2012, January 3). Usability 101: Introduction to usability. Nielsen Norman Group. http://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability

Potts, L. (2009). Using actor network theory to trace and improve multimodal communication design. Technical Communication Quarterly, 18(3), 281–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572250902941812

Potts, L. (2013). Social media in disaster response: How experience architects can design for participation. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203366905

Potts, L., & Bartocci, G. (2009). <Methods> Experience Design </Methods>. SIGDOC ’09: Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Design of Communication (pp. 17–21). https://doi.org/10.1145/1621995.1621999

Qualtrics. (2022). What is cluster analysis? When should you use it for your survey results? Qualtrics XM Talks. https://www.qualtrics.com/experience-management/research/cluster-analysis

Quesenbery, W. (2003). Personas: Bringing users alive. [PowerPoint presentation]. WQusability.com. https://www.wqusability.com/handouts/personas-overview.pdf

Salazar, K. (2018, January 28). Why personas fail [Web log]. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/why-personas-fail

Shivers-McNair, A., Phillips, J., Campbell, A., Mai, H. H., Yan, A., Macy, J. F., Wenlock, J., Fry, S., & Guan, Y. (2018). User-centered design in and beyond the classroom: Toward an accountable practice. Computers and Composition, 49, 36–47. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2018.05.003

Spinuzzi, C. (2005). The methodology of participatory design. Technical Communication, 52(2), 163–174.

St.Amant, K. (2018). Contextualizing cyber compositions for cultures: A usability-based approach to composing online for international audiences. Computers and Composition, 49(2018), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2018.05.007

Stake, R. (2000). Case studies. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 435–454). Sage Publications.

Statistics. (2021, January 6). US boat sales reached 13-year high in 2020, recreational boating boom to continue through 2021. National Marine Manufacturers Association. https://www.nmma.org/press/article/23527

Sun, H. (2013). Cross-cultural technology design: Creating culture-sensitive technology for local users. Oxford University Press.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security. (2016). Float plan central: Official site of the float plan. Retrieved July 8, 2022, from https://floatplancentral.cgaux.org

Verhulsdonck, G. (2017). Designing for global mobile: Considering user experience mapping with infrastructure, global openness, local user contexts and local cultural beliefs of technology users. Communication Design Quarterly, 5(3), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1145/3188173.3188179

Whorton, C. (2021, January 4). Categorical data, Jaccard’s coefficient, and multiprocessing. Towards Data Science. https://towardsdatascience.com/categorical-data-jaccards-coefficient-and-multiprocessing-b4a7bd5d90f6