By Barbara Jungwirth

INTRODUCTION

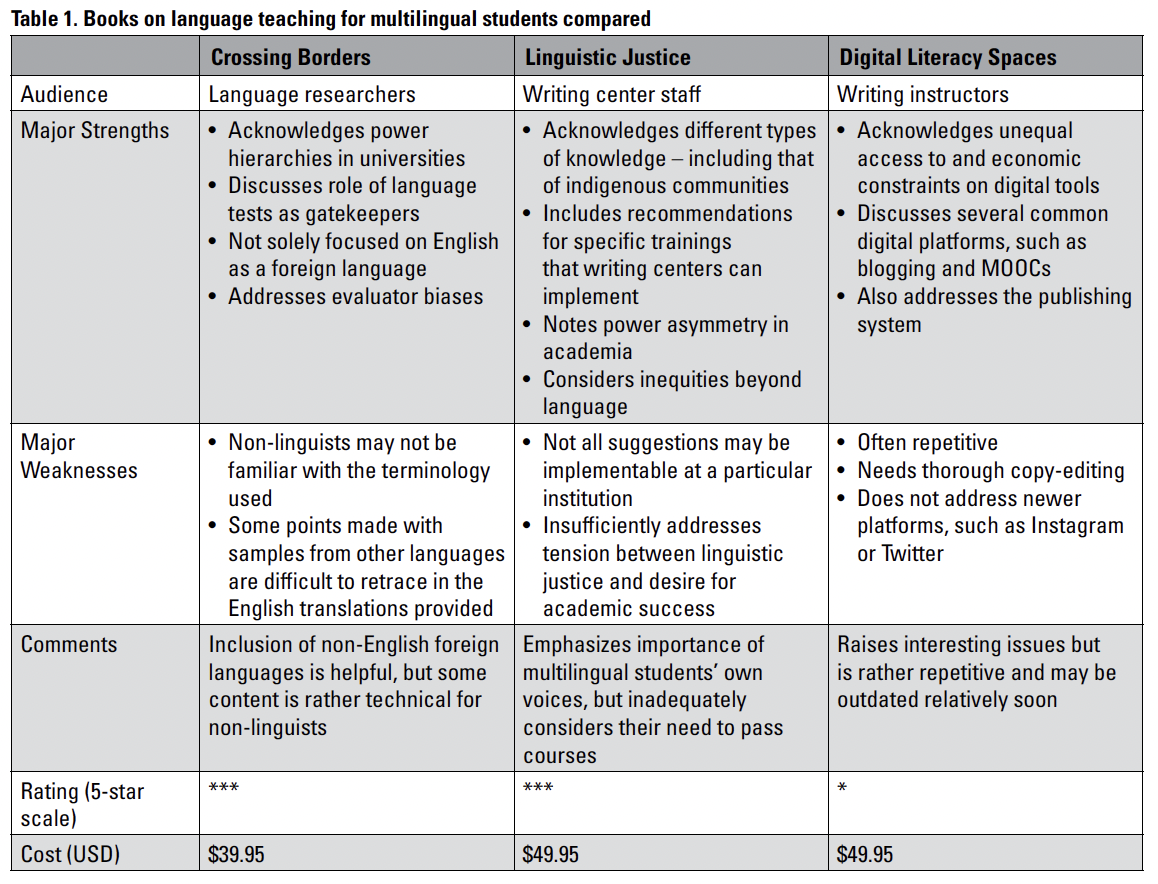

All three books are part of the “New Perspectives on Language and Education” series by Multilingual Matters and address teaching language to multilingual students at the university level (Table 1). Only Crossing Borders, Writing Texts, Being Evaluated: Cultural and Disciplinary Norms in Academic Writing considers languages other than English as foreign languages. It is a collection of studies, as is Linguistic Justice on Campus: Pedagogy and Advocacy for Multilingual Students, while Creating Digital Literacy Spaces for Multilingual Writers is authored by one person. All three books acknowledge inequities, but only the two collections note the power asymmetries inherent in academia in the Global North. Crossing Borders, Writing Texts, Being Evaluated seems most useful to researchers, especially those in linguistics. Linguistic Justice calls for validating students’ multilingual voices and provides recommendations for writing centers on how to do so but does not sufficiently address the competing student goal of passing courses with professors who may be focused on standard academic English. Creating Digital Literacy Spaces for Multilingual Writers discusses incorporating common digital platforms into teaching writing to multilingual students, but frequently repeats the same points. Read Linguistic Justice on Campus if you are looking for practical advice. Otherwise, read Crossing Borders, Writing Texts, Being Evaluated if you are interested in linguistic research.

CROSSING BORDERS, WRITING TEXTS, BEING EVALUATED: CULTURAL AND DISCIPLINARY NORMS IN ACADEMIC WRITING

CROSSING BORDERS, WRITING TEXTS, BEING EVALUATED: CULTURAL AND DISCIPLINARY NORMS IN ACADEMIC WRITING

Crossing Borders is a collection of studies focused on the cultural rather than linguistic issues encountered by people who study at the university level in the Global West. The book idea originated in symposia in New Zealand and the US. Three of its authors teach Norwegian and Finnish, respectively, as foreign languages, one teaches English in China, while the remainder work at institutions in English-speaking countries, such as New Zealand. Authors note that every academic discipline has its own vocabulary and conventions, which even native speakers of the dominant language—e.g., English—must learn. At the university level, pre-enrollment language tests act as gatekeepers for international students, even though test questions may have little relevance to the overt and covert conventions in a given field of study.

Crossing Borders is a collection of studies focused on the cultural rather than linguistic issues encountered by people who study at the university level in the Global West. The book idea originated in symposia in New Zealand and the US. Three of its authors teach Norwegian and Finnish, respectively, as foreign languages, one teaches English in China, while the remainder work at institutions in English-speaking countries, such as New Zealand. Authors note that every academic discipline has its own vocabulary and conventions, which even native speakers of the dominant language—e.g., English—must learn. At the university level, pre-enrollment language tests act as gatekeepers for international students, even though test questions may have little relevance to the overt and covert conventions in a given field of study.

Despite blind evaluation of tests, raters’ biases may creep in since a student’s first language can often be guessed based on specific non-standard phrases or grammatical features used. Even when such linguistic “deficiencies” were corrected, essays written in Norwegian by native Vietnamese speakers were rated differently from those written by native Spanish speakers, one study reported. This may be due to the rhetorical conventions common in the immigrants’ home countries compared to the rhetoric expected by the Norwegian raters.

In English-language universities, a specific variety of standard English may be expected. Students from India or Singapore who grew up speaking English have been told that their English is inadequate for studying at a New Zealand university. Such experiences may affect students’ belief in their ability to get a degree in their chosen field. Universities are also power hierarchies that students—native and immigrant alike—need to learn to navigate. However, differing concepts of authorship and textual appropriation, as well as approaches to hierarchies in general, may make such navigation more difficult for some international students.

LINGUISTIC JUSTICE ON CAMPUS: PEDAGOGY AND ADVOCACY FOR MULTILINGUAL STUDENTS

The collection of articles in Linguistic Justice on Campus focuses on English as a Second Language at North American universities. Articles include recommendations for changing academic writing centers’ approaches to supporting students unfamiliar with English for academic purposes. They also note that writing center volunteers may be monolingual English speakers who need training in validating non-standard expressions.

The collection of articles in Linguistic Justice on Campus focuses on English as a Second Language at North American universities. Articles include recommendations for changing academic writing centers’ approaches to supporting students unfamiliar with English for academic purposes. They also note that writing center volunteers may be monolingual English speakers who need training in validating non-standard expressions.

Different types of knowledge—including those of indigenous communities—and their inclusion at Western-style universities are also addressed. Teachers should survey their students’ language use, including switching between languages and registers depending on audience and situation, and combining features from two or more languages to articulate their thoughts in their own voices. Students’ diverse backgrounds can enrich class discussions and provide hitherto unconsidered approaches to assigned materials.

While writing in their own voice may be an important goal, students are also worried about how their professors might evaluate the texts they write. Ideally, speaking multiple languages or bringing a non-mainstream cultural background to class would be considered an asset. Unfortunately, that is not always the case. The book considers this tension between what should be and what is. However, it does not adequately address how to help students whose teachers do not value diversity in practice.

Beyond individual professors, not all institutions are likely to be receptive to implementing the suggestions for changes to writing center practices in some of the articles. However, it never hurts to try and even incremental changes may help multilingual students now and in the future.

CREATING DIGITAL LITERACY SPACES FOR MULTILINGUAL WRITERS

Unlike the other two books, Creating Digital Literacy Spaces for Multilingual Writers is written by a single author. It discusses the incorporation of several digital platforms and tools, such as blogging or massive online open courses (MOOCs), into teaching multilingual writers at the university level. Multimodality—the inclusion of images and sound—as well as “flipped learning” (p. 140), which provides more individualized experiences, are also covered as different forms of literacy. Bloch discusses helping students who may not be fluent in Standard English for Research Purposes to handle writing assignments in an academic environment. He also discusses how to prepare such students for publishing their research. Two of the eight chapters are devoted to publishing, including one on deciding where to submit research and on identifying predatory journals.

Unlike the other two books, Creating Digital Literacy Spaces for Multilingual Writers is written by a single author. It discusses the incorporation of several digital platforms and tools, such as blogging or massive online open courses (MOOCs), into teaching multilingual writers at the university level. Multimodality—the inclusion of images and sound—as well as “flipped learning” (p. 140), which provides more individualized experiences, are also covered as different forms of literacy. Bloch discusses helping students who may not be fluent in Standard English for Research Purposes to handle writing assignments in an academic environment. He also discusses how to prepare such students for publishing their research. Two of the eight chapters are devoted to publishing, including one on deciding where to submit research and on identifying predatory journals.

Another issue discussed at various points in the book is “textual borrowing” (p. 12). The extent to which text from other sources can be incorporated in a student’s own writing, as well as copyright laws, differ across the world. Similarly, expectations for critical assessment of material from published authors may not be clear to students from countries where such critique would not be welcome. Online sites that detect plagiarism may be helpful in teaching these distinctions. However, as with other digital tools, privacy concerns arise. Furthermore, digital spaces may not always be accessible or affordable, especially for students from the Global South.

Perhaps inevitable given how long the print publishing process takes, the author does not discuss newer digital platforms, such as Instagram. Also, the URLs and tools cited may be outdated long before a new edition of the book is printed. Creating Digital Literacy Spaces for Multilingual Writers raises several interesting issues. However, it would benefit from an editing pass to eliminate—sometimes verbatim—repetitions. Copyediting for standard English grammar and usage would also be helpful.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Barbara Jungwirth writes about medical topics (www.bjungwirth.com) and translates medical and technical documents from German into English (www.reliable-translations.com). She has written for print and online media since her high school days and majored in media studies. You can find her on Twitter at @bjungwirthNY.

REFERENCES

Bloch, Joel. (2021). Creating Digital Literacy Spaces for Multilingual Writers. Multilingual Matters. [ISBN 978-1-180041-078-7. 296 pages, including index. US$49.95 (softcover).]

Golden, Anne, Lars Anders Kulbrandstad, and Lawrence Jun Zhang, eds. (2021). Crossing Borders, Writing Texts, Being Evaluated. Multilingual Matters. [ISBN 978-1-78892-8557. 184 pages. US$39.95 (softcover).]

Schreiber, Brooke R., et al., eds. (2021). Linguistic Justice on Campus: Pedagogy and Advocacy for Multilingual Students. Multilingual Matters. [ISBN 978-1-78892-948-6. 248 pages, including index. US$49.95 (softcover).]