doi: https://doi.org/10.55177/tc986798

By Nora K. Rivera

ABSTRACT

Purpose: This article presents a UX study conducted during a roundtable collaborative event with Indigenous interpreters and translators. The work highlights the value of Indigenous testimonios as a UX method for gathering narratives that trace a user’s experience through a collective voice. Testimonios also trace users’ social and cultural contexts while prompting participants to exercise their agency and promote social change.

Method: This UX study engages Indigenous testimonios as a primary method. Mapping testimonios allows researchers to explore a participant’s narrative arc that begins with a personal experience that links a collective struggle resulting from a system of oppression and ends with a call for social change.

Results: Using testimonios as a UX method yielded data that traced individual and collective pain points that defined the critical issues with which Indigenous interpreters and translators grapple and emphasized their civic engagement, amplifying their agency through a method situated in their contexts. This work also highlights dialogue and desahogo, or emotional relief, as key elements of testimonios shared in a collective setting. This study shows that Indigenous interpreters and translators, as technical communicators, are foremost community activists.

Conclusion: A testimonio method prompts participants to reflect on issues at a deeper level through narratives and dialogue. It also engages the unique differences of participants while revealing general similarities. Testimonios can ultimately help design content, products, and processes that better align with the unique contexts of Indigenous individuals and other underrepresented groups who express their needs in a collective manner.

KEYWORDS: Testimonios, Indigenous methods, Indigenous interpreters and translators, UX research, Technical communication

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Testimonios are a valuable tool to design UX projects with individuals from underrepresented groups who express their needs as collective needs.

- This method can help practitioners understand important cultural and contextual differences when working with superdiversified (Cardinal, 2022) groups.

- The personal and collective narratives prompt participants to reflect on issues at a deeper level, engaging with their unique differences while revealing general similarities.

- Practitioners must invest time to build a relationship with participants when working with testimonios.

- Practitioners must view this methodology from an Indigenous lens, especially when working with the unique elements of desahogo, or emotional relief, and dialogue.

INTRODUCTION

Societies in the Americas have always been multicultural and multilingual. Before Europeans arrived in the Americas, the people on the continents spoke approximately 1,500 languages (Campbell & Mithun, 1998). Many languages were lost after colonization, and many have mutated into variants that today are treated as autonomous languages. In Mexico alone, 364 Indigenous linguistic variants exist today (INALI, 2008). As a result, Indigenous interpreters and translators have been essential for intercultural communication. Evidence shows that written translation took place as early as the 1st century between Nahua and Maya, as seen in the Mayan ceramic vessel found in Rio Azul, Guatemala, which is encircled with Nahua words in Mayan glyphs to describe the preparation of cacao (Macri, 2005). During the Spanish colony, moreover, Indigenous oral interpreters held government positions in Mexico and the Araucanian region (modern Chile) to help mediate between languages and cultures (Alonso & Payás, 2008). Language mediation in Indigenous languages in the Americas has been present for thousands of years.

Unsurprisingly, the complexities associated with interpreting and translating between two different worldviews (Indigenous and Western European) have triggered layers of difficulties for Indigenous interpreters and translators as technical communicators working in the legal, medical, and educational fields. As they mediate between languages, cultures, values, loyalties, and biases, Indigenous translators and interpreters continue to grapple with the Western systems that guard public institutions throughout the Americas today.

This study analyzes the experiences of Indigenous interpreters and translators through the Indigenous method of testimonios to identify the critical issues affecting them in their role as technical communicators. Testimonios are narratives that emphasize an individual’s wholistic relationship with a product, service, process, or content. Through a testimonio, an individual narrates a wholistic experience that links a personal account to the collective experience of the community to which the individual belongs, which yields valuable information to examine the cultural and social roots of an issue. In other words, this method yields information about the user’s full experience, hence the value of testimonios to UX research.

Testimonios differ from interviews in several ways. Instead of the researcher asking one question at a time, as in the case of interviews, testimonios draw on dialogue that seeks to understand the perspective of a group of people. Instead of using open-ended questions, testimonios use prompts to encourage individuals to tell their experiences through stories. Testimonio prompts are open enough to stimulate storytelling and dialogue between individuals sharing their experiences so that, in a roundtable setting, each participant becomes both the storyteller and audience. Rather than asking demographic questions, a testimonio prompt might ask, “what can you tell me about your background?” Instead of asking, “what specific feature of this product do you like the most?” a testimonio prompt might ask, “what can you tell me about your experiences with this product?” In many cases, the researcher participates in the dialogue by acknowledging what the participants share, asking clarifying questions, or introducing more prompts. Ultimately, the narrative of a testimonio reveals the cultural and social contexts of the challenges and motivations of a user. Testimonios are narratives that construct, and reconstruct (Mora Curriao, 2007), a personal account that embodies a shared collective experience.

This article demonstrates how an individual’s account can also represent the experiences of a community to identify the issues of a group. Because most testimonios produce a call for civic engagement (Delgado et al., 2012), testimonios can be a powerful method to define the issues affecting underrepresented groups while amplifying agency. Whereas UX designers do not often use this method, testimonios are gaining ground in the UX adjacent field of technical communication (TC), particularly through the work of Latinx practitioners and scholars working with Latinx communities (Gonzales et al., 2020; Medina, 2018; Phillips & Deleon, 2022; Rivera & Gonzales, 2021). This study aims at answering the following questions:

- How can testimonios help identify the issues affecting Indigenous interpreters and translators in their role as technical communicators working in the legal, medical, and educational fields?

- How might UX researchers engage with testimonios as an Indigenous method that promotes agency and supports user advocacy?

This study highlights the value of testimonios as an Indigenous approach to UX research that increases user agency and supports self-advocacy. This study also discusses how testimonios conducted in a roundtable setting can help build community, or connections, between individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds and between practitioners and academics. Most importantly, this work helps to design more meaningful experiences for Indigenous professionals.

Although Indigenous individuals might not be the core audience of most technical communicators working in UX design, this study can help identify meaningful strategies that better engage Indigenous users. Furthermore, understanding the complexities enveloping cultural identities can help technical communicators identify their audiences with more precision and, therefore, design more meaningful experiences for diverse users.

WORKING DEFINITIONS OF CULTURAL IDENTITIES

Designing experiences for multicultural and multilingual audiences today require not just empathy but a deep comprehension of the various cultural contexts informing their views and preferences. As immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean become more visible in the US, it is crucial to understand the nuances between the various identities that make, according to the United States Census Bureau (Vespa et al., 2020), the largest immigrant combined group in the United States (US) and the fastest-growing demographic group. Cardinal (2022) argued that global migration has increased the complexities associated with cultural identities, exposing an in-flux “diversification of diversities” phenomenon known as superdiversity (p. 2). Superdiversities have always been present in the Americas, but they have not always been visible in the US. For example, the term Hispanic is used in most public institutions in the US to identify all individuals with Latin American heritage without weighing the differences between Indigenous individuals from Mexico and Mexican Mestizas/Mestizos and Mexican Americas, or Mexicans and Puerto Ricans, or Colombians and Peruvians. We are all lumped in the same Hispanic category whether we speak Spanish or not. The term Hispanic implies a Spanish cultural and linguistic heritage that leaves out heritages of Indigenous and Afro-descendant individuals.

Although this work focuses on the experiences of Indigenous individuals, other ethnic and cultural identities also contextualize this study and, therefore, require some clarification, with the understanding that this list in no way intends to cover the full extent of the many cultures that individuals and groups with Latin American heritage represent in and outside the US.

- Indigenous. This is the most generally accepted term to refer to individuals who self-identify as Indigenous and are recognized and accepted by an Indigenous community (UN, 1982). Although the term is complex and does not universally describe all individuals of Indigenous heritage, individuals who belong to Indigenous communities in this study self-identified with this term. Some Indigenous individuals in the US with Latin American heritage may also self-identify as Latinx. Others with Mexican heritage may also self-identify as Chicanxs, and those with African heritage may also self-identify as Afro Indigenous.

- Mestiza (for female), Mestizo (for male), Mestizx/Mestiz@/Mestize (gender-inclusive neologisms). During colonial Mexico, Spaniards used the terms Mestiza and Mestizo to define individuals with both Spanish and Indigenous ancestry. However, these terms have come to signify individuals of mixed race who favor the Western traditions and practices inherited from the Spanish colonial systems (e.g., public schools, public health institutions, and courts). Indigenous individuals from Mexico use these terms to describe non-Indigenous individuals with Mexican heritage. Indigenous individuals from Central America use the terms Ladina and Ladino to describe Westernized, non-Indigenous individuals (Ladines is not a gender-inclusive neologism commonly used). Most Mestizes in the US self-identify as Latinxs. Not all non-Indigenous individuals with Mexican heritage self-identify as Mestizes; some self-identify as Afro Mexicans or White.

- Chicana (for female), Chicano (for male), Chicanx/Chican@ (gender-inclusive neologisms). Many individuals born in the US of Mexican descent self-identify with these highly political terms. These terms emerged from the Chicano Movement (part of the Civil Rights Movement) to convey strong pride in Mexican roots (primarily Mexican Indigenous roots). The Chicanx culture should be understood as a new culture proud to belong in between two cultures, the U.S. Anglo and the Mexican (like the Spanish and Indigenous cultures gave birth to the Mestize culture during the colonial era in Mexico). Additionally, the term Chicana is strongly associated with feminist activism because of the powerful social and political presence that Mexican American feminists have had over the years in and outside academia. Not all U.S.-born Mexican Americans self-identify as Chicanxs. Some Indigenous individuals of Mexican descent self-identify as Chicanxs. Chicanxs may also self-identify as Indigenous, Afro-Latinxs, Mestizes, or Latinxs.

- Latina (for female), Latino (for male), Latinx/Latine (gender-inclusive neologisms). The neologism Latinx has become the most generally accepted term in U.S. academic realms to describe individuals with Latin American heritage. Individuals in Latin America, however, are more familiar with the term Latine. Some Indigenous individuals may not subscribe to a Latinx identity. Most African descendants with Latin American heritage self-identify as Afrodescendientes (Afro Descendants), Afro Latinxs, or Blacks.

Whereas Latinx is perhaps the most inclusive term today to envelop individuals with Latin American heritage, Latinx individuals are multicultural and very often subscribe to more than one cultural identity. The languages we speak also reflect a superdiversity among Latinx individuals as many of us are multilingual, not just in European languages imposed in the Americas through colonization, like English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, and Dutch, but also in the many Indigenous languages of the Americas.

Indeed, a great deal of hybridity exists in Latin America and the Caribbean, and, therefore, cultural identities do not always relate to race or country of origin. Cultural identities reflect the customs and traditions that an individual or a group prefers, such as the case of Chicanxs who may be born to an Anglo parent but identify with their Mexican roots, or Mestizes whose mixed cultural identities are complex as some may feel more connected to their Indigenous roots whereas others favor their European ancestry. Additionally, cultures change over time, and thus so do cultural identities (Sun, 2012). Geopolitics (political relations influenced by the geographical space) can also quickly alter cultural identities, as has been the case of many White Latin Americans who immigrate to the US and become People of Color (POC) in months.

The nuances of cultural identities are essential to understanding users’ motivations and why they might find certain aspects of what technical communicators design more challenging than others. Global historical contexts matter. When working with Indigenous and Latinx groups, for example, going beyond understanding language differences and acknowledging that not all groups can relate to Western systems is key. Although the US became a country independent from Great Britain in the 1700s and most countries in Latin America gained their independence from Spain in the 1800s, Western systems continue to govern the Americas (Quijano, 2000; Rivera Cusicanqui, 1987). By and large, Anglo American traditions regulate public institutions in the US in the same way that the Westernized praxes of Mestizes, Lidinas and Ladinos regulate public institutions in Latin America today, not to mention that Western European languages remain the official languages throughout the Americas.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Cultural identities are key when working with a testimonio methodology, as this study shows. Testimonios stem from the Indigenous oral traditions of dialogue, storytelling, and advice. For example, ancient Nahua huehuehtlahtolli, or wise dialogues, consisted of storytelling narratives imbued with advice (León-Portilla, 1991). Testimonios as we understand them today trace back to Rigoberta Menchú’s (1984) I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian woman in Guatemala, where Menchú narrated her experiences as a survivor of the Guatemalan Civil War and provides a glimpse at her community-based practices—critical to understanding Indigenous worldviews.

However, Menchú’s way of understanding the world has critics who, by pointing out inaccuracies in her facts, question the validity of testimonios “on the grounds of ‘historical inaccuracy,’” ignoring that “the political and collective import of the genre transcends the overreliance on the authority of dominant historical fictions as the determining factor for what is true for all experiences,” as Medina (2018, “Storytelling” section) noted. Some critics also question the validity of Menchú’s testimonio because a translator mediates the story (Medina). Menchú, a Maya-K’iche’ speaker, did not write in Spanish at that time; therefore, a translator recorded Menchú’s oral testimonio and published the book in Spanish. This article displays traces of both the issue of undermining Indigenous practices—like testimonios—and the issue of questioning the validity of a translation or an interpretation when involving Indigenous individuals.

A testimonio is a qualitative method that is more common in Latinx and Latin American contexts (Smith, 2012). As the Latinx population continues to grow in the US, more and more practitioners and academics working with Latinx individuals use this method because it resonates with Latinx and Latin American cultures. The dialogical process of sharing and listening to testimonios produces a thoughtful conversation among participants and researcher(s), which is key to building empathy and trust. For this reason, the scholarship and practices of Chicana and Latina feminists often include this method. In short, testimonios exhibit the following characteristics:

- Reconstruct a lived experience through a narrative (storytelling)

- Link a personal narrative to a group’s collective experience

- Acquire a reflective dialogical tone

- Call for civic engagement to produce social change

- May involve desahogarse as a cathartic act of releasing distressful sentiments (desahogo, a noun, means emotional relief and desahogarse, a reflexive verb, is the action of releasing a desahogo)

The personal narrative in testimonios constructs and reconstructs a lived personal account that connects to a collective experience (Benmayor, 2012; Mora Curriao, 2007). When sharing testimonios, participants often switch from “I” statements, such as “I experienced. . .”

or “When I. . .,” to “we” statements, such as “In my community. . .” or “My family and I. . .” Sometimes there is no clear separation between the individual and the collective because our interactions with others influence our personal experiences (Gonzales et al., 2020). Most Latinx and Latin American cultures are collectivists as they emphasize the family or the community over the individual—the welfare of the community is even more important in Indigenous contexts, hence the importance of considering the experiences of the family and community when conducting UX research with Latinx and Indigenous individuals or groups.

Further, because testimonios are not neutral narratives of disconnected narrators, they are political. The narratives have a social and political purpose (Benmayor, 2012). Testimonios increase the participants’ visibility and empowerment by allowing them to freely express their attitudes and emotions. As a result, many times testimonios climax in a cathartic desahogo, or emotional relief, that prompts participants to arrive at a point of “enough is enough” (Rivera, 2022; Rivera & Gonzales, 2021). Subsequently, participants begin working toward finding solutions to the issues discussed. Phillips and Deleon (2022) called this the “healing discourse” of testimonios because it allows others to listen to the emotional relief of individuals who share their experiences and motivates the group to explore different possibilities toward changing an experience for the better.

In the context of this study, the concept of desahogo emerged during the sharing of testimonios, when participants collectively arrived at a point where they had pondered on issues enough to arrive at the conclusion that it was time to act to challenge the issues they struggle with. Some of the participants also brought up the concept of desahogo as the emotional cathartic act that Indigenous individuals experience in the presence of an interpreter who speaks their language. Frequently only natives from a specific Indigenous community speak the community language variant, and thus Indigenous individuals for whom interpreters provide a service feel an instant connection with the interpreter. This study discusses desahogo as part of the testimonios of the participants and as part of an Indigenous interpreting process when providing services to Indigenous individuals under stressful circumstances while navigating Western systems.

Like the arc of storytelling, a testimonio builds a narrative, then climaxes at its peak with a desahogo—usually when participants realize that they have said enough (similar to venting) to finally decompress the narrative by working toward a resolution. Even though storytelling does not necessarily aim at advocating for social justice, storytelling becomes the conduit for testimonios to do so (Medina, 2018). Through testimonios, participants examine issues within a larger social and cultural context and, therefore, are inspired to find solutions that incorporate their own civic engagement to help produce social change.

Nonetheless, testimonios do not intend to find a hasty fix to an issue, especially issues affecting underrepresented groups (Gonzales et al., 2020). They aim at reflecting on the causes and bringing about a call to action. Unlike interviews, the method of testimonios is a process to a deeper understanding of the causes of complex issues, prompting the participants to contemplate various ways of solving the issues through collective reflection and civic engagement. This can be particularly helpful for UX designers when working with individuals from various cultural backgrounds who might understand a problem differently. “Understanding the gap between our viewpoints,” Tuck and Yang (2018) argued, allows individuals from different cultural backgrounds to “work together in contingent collaboration” (p. 2). Promoting action and civic engagement via testimonios increases user agency and, therefore, drives UX designers to a more inclusive multicultural approach to solving problems.

METHOD

To conduct this study, I collaborated with Indigenous individuals with the utmost respect and admiration for their knowledges, from the positionality of a Mestiza who values the common heritage and the shared history. This study aimed to identify the issues affecting Indigenous interpreters and translators as technical communication practitioners and explored ways to professionalize their work. As is the norm in a qualitative testimonio methodology, this study used a small sample size (Benmayor, 2012; Delgado et al., 2012; Gonzales et al., 2020), allowing enough occasion for storytelling, dialogue, and reflection.

Although each participant represented a community with unique traditions, this superdiversified group (as Latinx groups often are) shared very similar experiences in their role as practitioners of Indigenous language mediation, which is the focus of this study. Through testimonios, each participant narrated how the various fields and the geopolitics of the spaces they work in influence their praxes, revealing important differences within the commonalities they shared. The testimonios of this superdiversified group yielded twofold data: 1) the general, shared issues of Indigenous interpreters and translators when navigating Western systems, and 2) the unique issues that each participant, both personally and collectively, faced within the context of the community each represents. Testimonios in this study also yielded data about the civic engagement that each participant takes part in, which is a common practice among professionals who belong to underrepresented groups (e.g., many professionals of color belong to organizations associated with their cultural identity). The value of testimonios lies in the personal-collective twofold data they yield and the civic engagement that leads to a call to social change that increases user agency, thus making testimonio mapping a stronger method for engaging Indigenous populations.

An Indigenous organization, the Centro Profesional Indígena de Defensa y Traducción (CEPIADET), guided this study (IRB/FWA No. 00001224). CEPIADET invited Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals as well as academics and practitioners to participate in this study to discuss the issues from various cultural and professional perspectives. Pseudonyms were used to protect the privacy of the participants.

The testimonios were shared in a roundtable setting guided by two prepared prompts from where the participants built their narratives. The first prompt was, “Can you tell us your name and your background?” Participants were given about 5 minutes (in both instances) for individual introductions. A protocol of introductions where individuals emphasize their place of origin is also an Indigenous method that helps locate the lens, or perspective of the world, of each participant (Kovach, 2010). Participants each took about 5 minutes (in both instances) to introduce themselves, providing information such as name, place of origin, place where they live now (because some have emigrated to different cities or countries), languages they speak, and the field and place where they work.

After the introductions, participants were given the second prompt, “What can you tell us about the issues you face as an Indigenous interpreter and translator in your community?” Each participant was given a time limit of 15 minutes. As a general guideline, they were also informed that they could ask questions and make comments after each contribution. During each contribution, the rest of the participants listened attentively, engaging in dialogue at the end of each participation. All communication was conducted in Spanish. The contributions were audio-recorded and then transcribed and translated from Spanish to English.

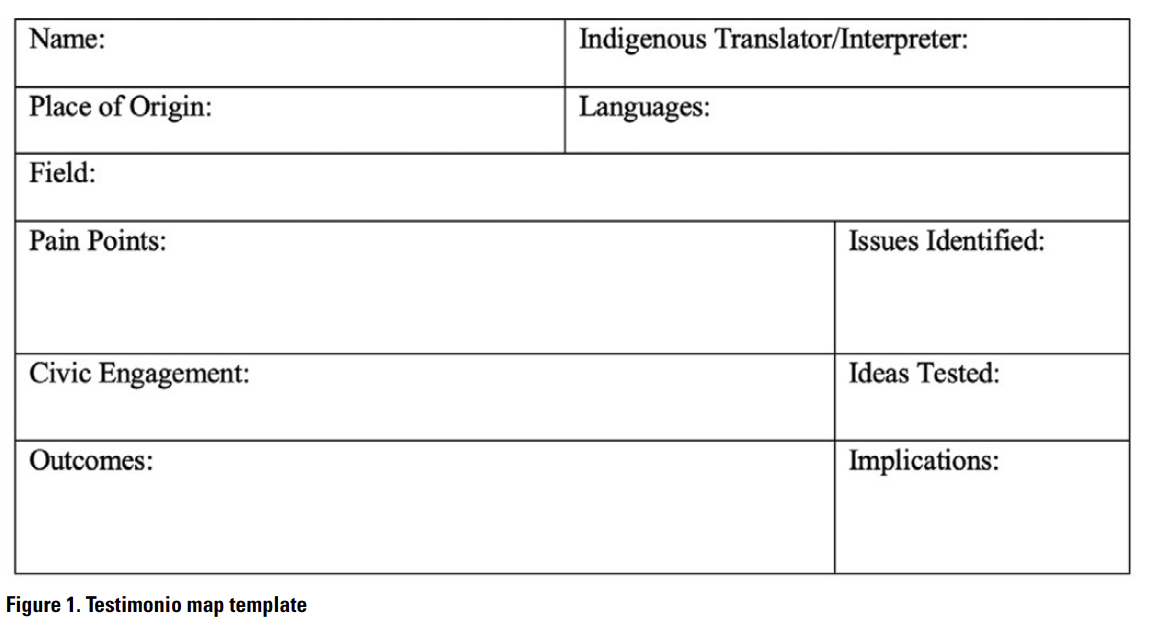

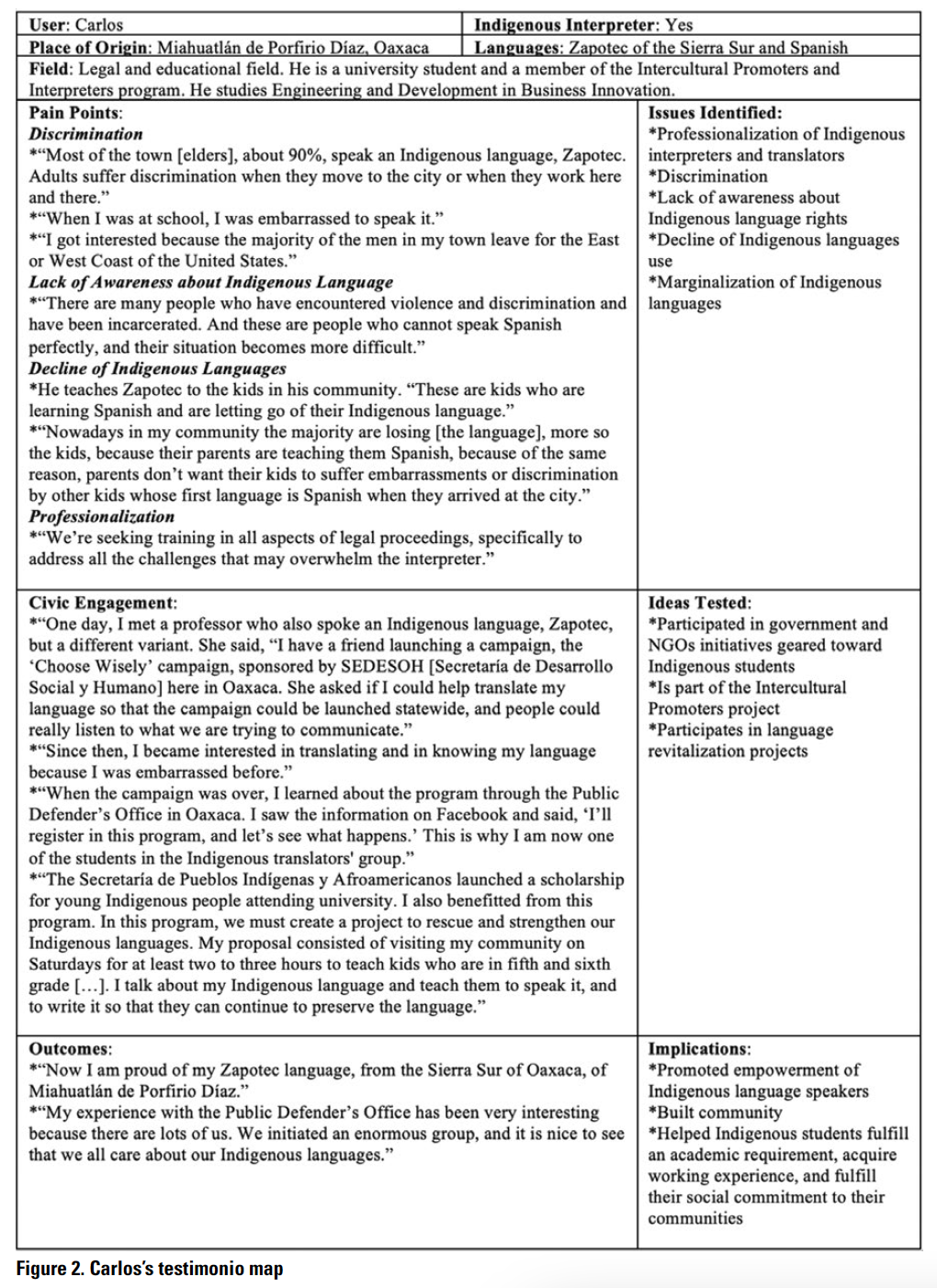

To analyze the experiences in the testimonios, I crafted a table similar to Wible’s (2020) user empathy maps. This table, which I call testimonio map, traced the individual and collective pain points, or specific problems that users experience (Stanford d.school, 2020). As shown in projects by the Stanford d.school, UX designers map user pain points to identify the specific issues of a user’s experience, create empathy among participants and researcher(s), and generate possible solutions that can improve the user’s experience. Testimonio mapping, however, goes beyond individual experiences as it also traces collective pain points. Additionally, because testimonios in this study also narrated approaches that participants have taken to overcome their pain points, the testimonio maps in this study also traced these approaches as civic engagement activities, mapping also the outcomes resulting from these civic engagements. In addition to pinpointing whether a participant self-identified as Indigenous, the maps also traced the place of origin, the field, and the languages that participants speak to situate each unique context.

Testimonio maps were divided into three rows that directly stem from the arc of testimonios. In the first row, individual and collective pain points were identified on the left. Direct quotes were used to identify the pain points, from where thematic issues were extracted and then placed on the right side of the first row. The civic engagements in which the participants take part based on what they quoted during their testimonios were mapped in the second row, from where thematic strategies to counteract pain points were extracted and coded as ideas “tested.” The last row was used to identify the outcomes of their civic engagements on the left and the implications of these outcomes on the right (Figure 1).

After completing all individual testimonio maps in a word processing software, as the example in Figure 2 shows, themes of the main elements in the map were extracted and written in sticky notes. This sticky note strategy was used to identify and synthesize thematic categories. Although this approach may seem simplistic, it is a process that allows designers to center their attention on the process of the possibilities rather than on the outcome (Wible, 2020). Writing on sticky notes the individual themes gathered from the pain points allowed me to easily move the information to organize it according to themes. Lastly, the sticky notes were organized by collective themes and placed in a collective testimonio map poster that gathered all thematic pain points, civic engagement activities, and implications of such engagements. Whereas the sticky note strategy was not done in collaboration with the participants because of lack of time, this strategy can and often is done in a collaborating environment. Lastly, the information was coded without the help of digital software, but research software can be very helpful in identifying thematic categories in testimonios.

After completing all individual testimonio maps in a word processing software, as the example in Figure 2 shows, themes of the main elements in the map were extracted and written in sticky notes. This sticky note strategy was used to identify and synthesize thematic categories. Although this approach may seem simplistic, it is a process that allows designers to center their attention on the process of the possibilities rather than on the outcome (Wible, 2020). Writing on sticky notes the individual themes gathered from the pain points allowed me to easily move the information to organize it according to themes. Lastly, the sticky notes were organized by collective themes and placed in a collective testimonio map poster that gathered all thematic pain points, civic engagement activities, and implications of such engagements. Whereas the sticky note strategy was not done in collaboration with the participants because of lack of time, this strategy can and often is done in a collaborating environment. Lastly, the information was coded without the help of digital software, but research software can be very helpful in identifying thematic categories in testimonios.

Traditional UX research methods, like interviews and empathy maps, focus primarily on the user experience with a specific element (product, process, or content) in a specific setting. Testimonios, however, render information about the full user experience, tracing the collective struggle of a community and promoting user agency through the call to action embedded in this important approach. Testimonios, however, have a particular goal that does not apply to all UX projects. Although testimonios can yield quantitative data, this is not their primary aim. Testimonios, as explained throughout this study, aim at building community, or connections, among participants and researcher(s) to understand complex problems at their social and cultural roots, hence the importance of situating a personal experience within the collective cultural and social contexts of each participant. Testimonio mapping expands the traditional mapping methods because it can be used in a group setting and can trace the collective voice and the civic engagement of the participants, which empathy maps struggle to accomplish.

Traditional UX research methods, like interviews and empathy maps, focus primarily on the user experience with a specific element (product, process, or content) in a specific setting. Testimonios, however, render information about the full user experience, tracing the collective struggle of a community and promoting user agency through the call to action embedded in this important approach. Testimonios, however, have a particular goal that does not apply to all UX projects. Although testimonios can yield quantitative data, this is not their primary aim. Testimonios, as explained throughout this study, aim at building community, or connections, among participants and researcher(s) to understand complex problems at their social and cultural roots, hence the importance of situating a personal experience within the collective cultural and social contexts of each participant. Testimonio mapping expands the traditional mapping methods because it can be used in a group setting and can trace the collective voice and the civic engagement of the participants, which empathy maps struggle to accomplish.

In larger holistic studies, testimonios work well in combination with other quantitative methods. Additionally, testimonios should be used with adult audiences with enough experience to convey a personal and collective narrative, which young adults may or may not have. This method is not a tool to use in impersonal settings (like a survey via email). Researchers must invest time to build a personal connection with individuals sharing testimonios, in person or through digital video conference applications. Most importantly, to understand the value of testimonios, researchers might have to invest time and effort to learn to shift the perspective to an Indigenous lens.

RESULTS

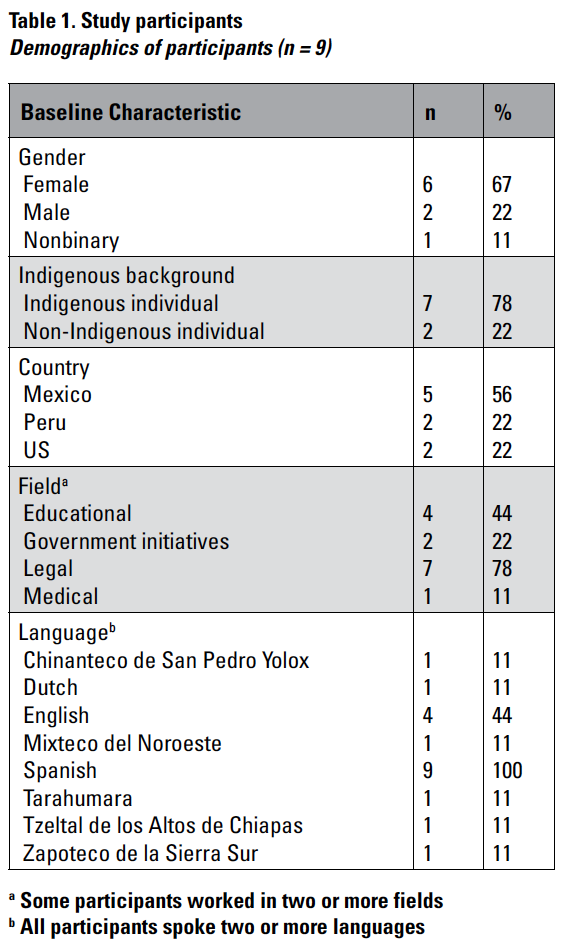

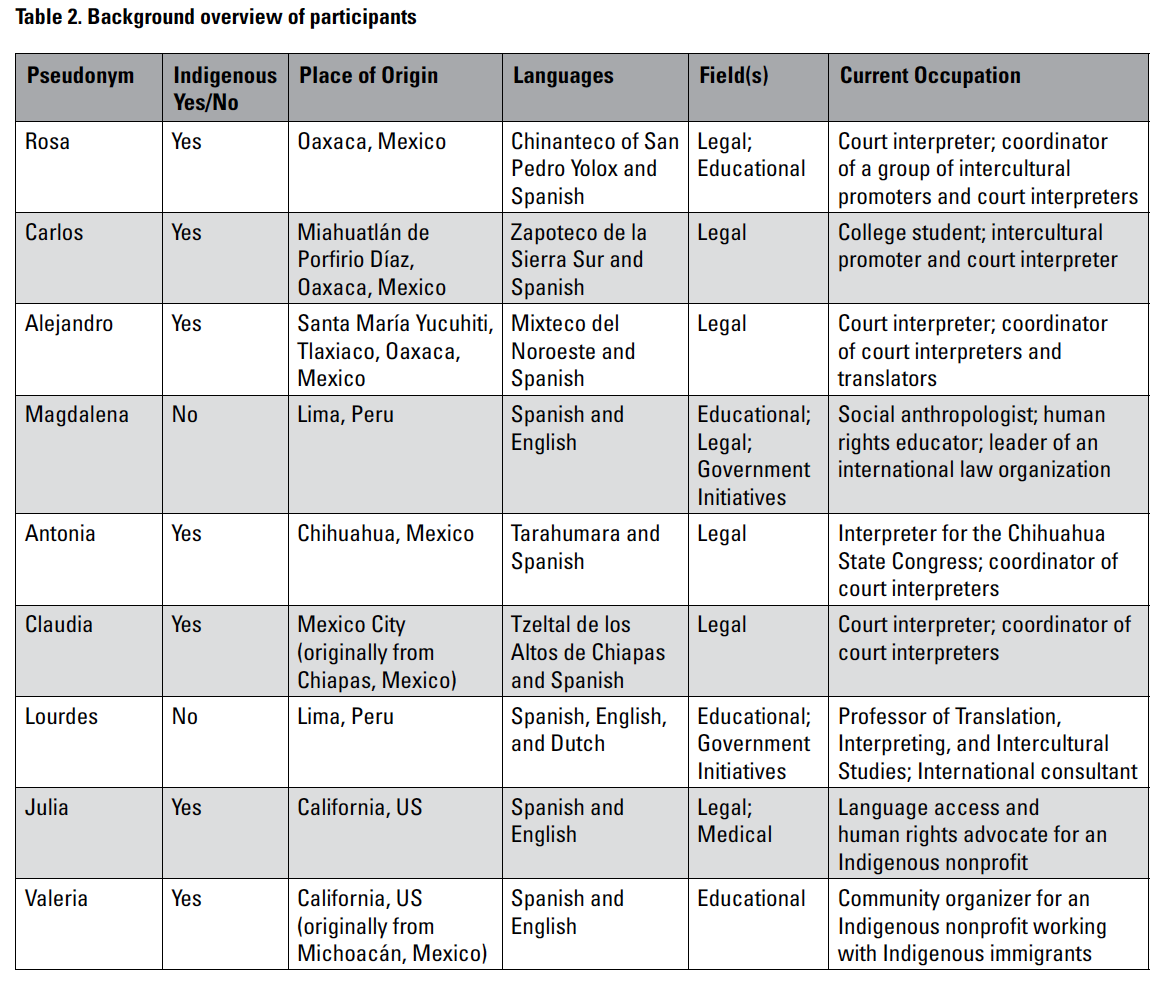

This study examined nine testimonios: seven from Indigenous practitioners and two from non-Indigenous academics who work with Indigenous practitioners and who bring experiences as collaborators of Indigenous language mediators in different geographical spaces. This multicultural and multilingual group had diverse characteristics (Table 1).

All combined, the participants represented eight different languages, five of which were Indigenous languages. All communication was conducted in Spanish because it was the language that all participants spoke. All participants spoke at least two different languages and several of them worked in more than one field. The participants’ backgrounds were also diverse (Table 2).

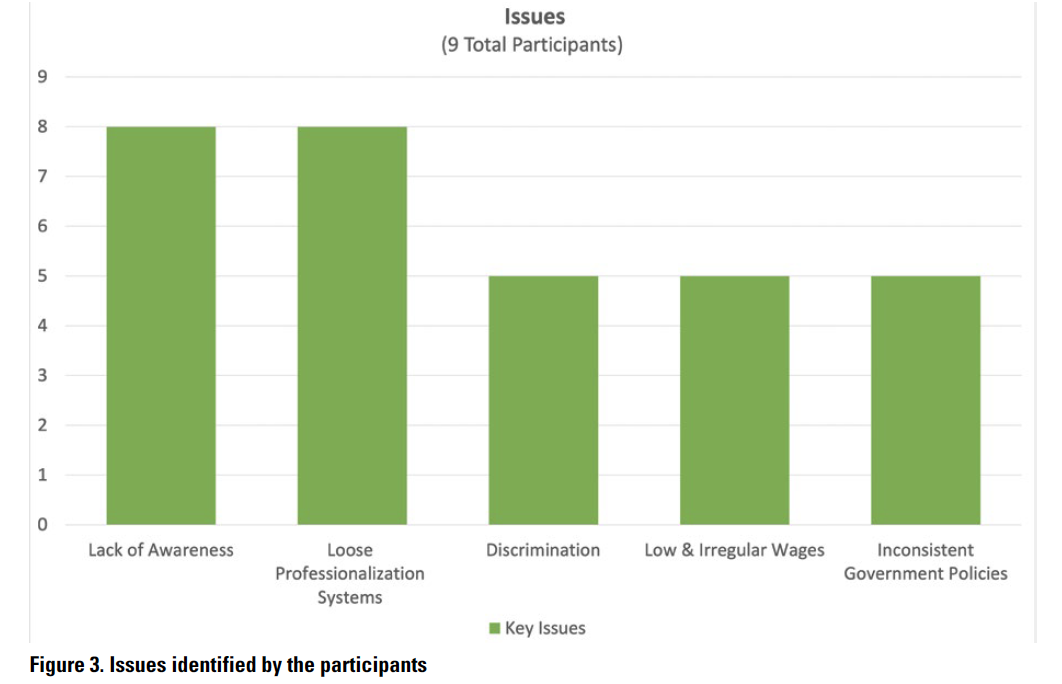

Testimonio mapping indicated the pain points with which Indigenous interpreters and translators grapple from both an individual perspective and a collective lens. Synthesizing the thematic issues uncovered through testimonios exposed a series of palpable issues that Indigenous professionals face in the field of interpreting and translation, such as loose professionalization systems and low and irregular wages (Figure 3). This section shows that these palpable issues sprout from more systemic problems, such as inconsistent local government policies, discrimination, and lack of awareness about Indigenous matters.

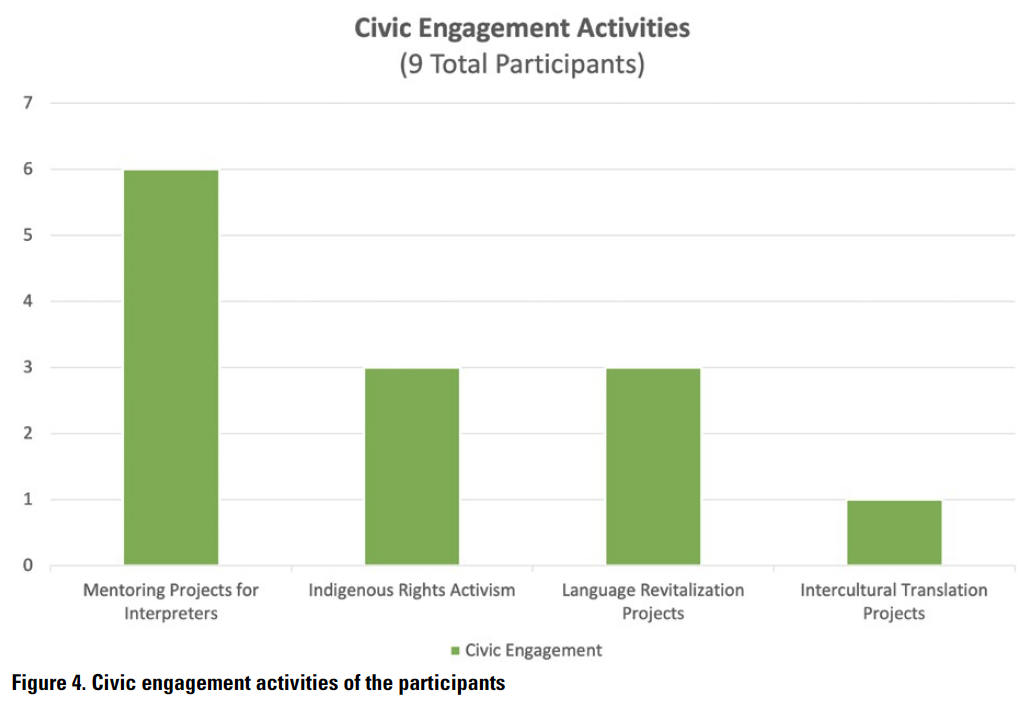

Testimonio mapping also revealed the important civic engagement activities in which participants take part to counteract the issues in their profession, as Figure 4 shows. Of the nine participants, six revealed that they take part in programs that mentor Indigenous interpreters and translators, preparing them not only with linguistic and technical strategies but also with information about how to navigate Western public systems to help their own communities; three participants engage in Indigenous rights activism through local and international initiatives; three participants take part in Indigenous language revitalization projects; and one participant is involved in intercultural translation projects that bridge collaborations between universities, government institutions, and Indigenous communities.

Testimonio mapping also revealed the important civic engagement activities in which participants take part to counteract the issues in their profession, as Figure 4 shows. Of the nine participants, six revealed that they take part in programs that mentor Indigenous interpreters and translators, preparing them not only with linguistic and technical strategies but also with information about how to navigate Western public systems to help their own communities; three participants engage in Indigenous rights activism through local and international initiatives; three participants take part in Indigenous language revitalization projects; and one participant is involved in intercultural translation projects that bridge collaborations between universities, government institutions, and Indigenous communities.

The research identified five pain points: lack of awareness, loose professionalization systems, discrimination, low and irregular wages, and inconsistent local government policies.

Pain Point One: Lack of Awareness

Lack of awareness about Indigenous matters is an issue that eight of nine participants indicated, pointing out that misconceptions about Indigenous matters and Indigenous linguistic rights among public officials and public workers cause many serious problems for Indigenous people.

Magdalena, a social anthropologist from Peru and human rights educator who works with Indigenous communities on topics related to globalization, gender, Indigenous rights, and intercultural communication, explained how working with Indigenous translators helped her institution recognize the need for creating alliances between academia and Indigenous communities to help and learn from one another. She discussed how most universities in Peru do not offer a formal translation and interpretation degree in Indigenous languages and how this became a problem when she got involved in a project where the government of Peru worked with the Department of Translation and Interpreting Studies at the Universidad de Ciencias Aplicadas de Perú to translate birth, death, and marriage certificates from Spanish to the Achuar Indigenous language. In her testimonio, Magdalena explained that the Amazonian town of Achuar del Pastaza asked the government to provide them with bilingual “vital event” documents, such as birth, death, and marriage certificates so that Achuar individuals could understand them:

These certificates are made by the Registro Nacional de Identificación y Estado Civil [RENIEC], which is the institution in charge of giving your DNI [Documentación Nacional de Identidad (National ID)]. If someone dies, they give a certificate, and also when someone is born so that these individuals can acquire a DNI.

However, as Magdalena commented, her institution could not find Achuar translators, so they ended up teaching Achuar-Spanish bilingual teachers to use technical translation strategies and software to work on the documents. Even though this project was a great example of intercultural and interinstitutional work, Magdalena questioned why the government took over 500 years to translate certificates that validate the identity of a human being into the language of the person who holds it and why most higher education institutions are not including Indigenous languages in their academic offer.

Claudia pointed out that the issues affecting Indigenous people sometimes are more accentuated within Indigenous migrant communities. Claudia belongs to a Tzeltal community from Chiapas but has lived in Mexico City for over 20 years. She explained that as an Indigenous migrant, she sees the indifference of the local government toward her Tzeltal migrant community in the city. During her testimonio, she explained how other migrant Indigenous communities in Mexico City face the same issues and informed us that after the Triqui community challenged the indifference of the local government toward their problems, violence and discrimination, the local government began paying more attention to other Indigenous migrant communities in the city:

There is a constant struggle, but since the Triqui Indigenous movement in Mexico City, public policies in Mexico City have paid more attention to the Indigenous migrant population [. . .] because when there are Indigenous migrants, the local government washes its hands because they think that’s not their problem.

Like Claudia, Valeria has also seen indifference toward Indigenous migrant communities in the US. Valeria is originally from the Mexican state of Michoacán but works as a community organizer for an Indigenous nonprofit in California. She helps Indigenous immigrants from Mexico and Central America to communicate better with their children’s school districts through Indigenous interpreters. Valeria explained that sometimes Indigenous migrant communities can be invisible to the public systems; therefore, she advocates for Indigenous language rights in the school districts in the community where she lives: “The most important thing for us, for the interpreter, for the district liaison, and for me, is to ensure that Indigenous immigrants are heard in the school districts.”

Alejandro was another participant who discussed the lack of awareness as a major pain point. He works as a court interpreter and coordinator of interpreters and translators at a nonprofit organization in Oaxaca, Mexico. Alejandro explained that although several national and international laws protect Indigenous language rights, in practice, many Indigenous people do not know them, and local governments do not always respect these laws.

Pain Point Two: Loose Professionalization Systems

Participants indicated that loose professionalization systems that do not address the needs of Indigenous interpreters and translators is also one of the most prevalent issues in their field. Of the nine participants, eight mentioned this pain point as a top priority. Participants identified a series of professionalization-related issues specific to their work fields. Julia, a language-access and human-rights advocate working for an Indigenous nonprofit in California, explained that “[i]n the US, there’s no certification for Indigenous languages of Mexico. There are legal and healthcare field certifications at the national level, but for other languages.” U.S. courts, she explicated, have three interpreter certification categories with different pay scales. The top certified interpreter program is only available for Spanish, Navajo, and Haitian Creole. Individuals at the top level must pass a written and oral exam given by the U.S. Courts Administrative Office that shows expertise in English and one of these three languages. The middle professional qualified interpreter program applies to all other language interpreters only if they meet a strict criterion that includes passing a U.S. Department of State exam or a UN exam in English and the target language. The low language skilled/ad hoc interpreter program requires individuals to demonstrate their language ability at court proceedings to and from English and the target language (detailed information about the court certification programs can be found at https://www.uscourts.gov/services-forms/federal-court-interpreters/interpreter-categories).

Therefore, as Julia indicated, to work and to be remunerated as a top-tier certified interpreter of Indigenous languages in U.S. courts, individuals must have at least a high school diploma and demonstrate mastery in at least three languages (Spanish, English, and their Indigenous language), which are not always realistic requirements considering the background of these professionals. Julia explained that she works with Indigenous immigrants to find resources to help them navigate certification requirements in both the medical and the legal field through coalitions with Mexican organizations.

Alejandro indicated that Mexico has systems to certify Indigenous interpreters and translators similar to the ones in the US (by educational levels); however, two government organizations that are clearly under-resourced handle these certifications. Underfunding triggers other issues like lack of professional follow-up. As Alejandro pointed out, “who wouldn’t want a certification? But not if they leave [interpreters] alone in the journey without continued training and evaluation.”

As an experienced court interpreter, Alejandro also explained that because Indigenous interpreting events often take place under stressful circumstances, Indigenous language speakers are often inclined to desahogarse (to release distressful emotional sentiments; similar to venting) with the Indigenous interpreter; however, Western interpretation protocols prohibit interpreters from engaging in any form of personal communication with anyone for whom they interpret. Alejandro expressed that he wishes protocols would allow Indigenous interpreters to interact with Indigenous individuals before the formal interpretation begins to better understand the situation’s context and better manage the desahogo because it inevitably happens during an interpretation process. He also said that interpreting courses do not teach them how to handle these stressful situations.

In the case of interpreting services in medical facilities, Julia explained that there is a robust system of healthcare interpreters in the US. Still, interpreters of Indigenous languages working in this industry must demonstrate proficiency in their Indigenous language and both English and Spanish, like in the legal field. Alejandro and Magdalena explained that although there are certification systems for Indigenous interpreters who work in the medical field in Mexico and Peru—the same as court interpreters, it is not common for healthcare providers to hire the professional services of Indigenous interpreters in these countries. In the medical field, Indigenous interpretations occur, but at an informal, mostly unpaid, level.

Like medical interpreters, professional interpreters in the educational field are not common in Latin American countries like Peru and Mexico. In the educational field, as Alejandro and Magdalena explained, bilingual teachers or children often provide the interpretation services needed, causing another complex ethical layer about the role of children as language brokers. In schools in the US, bilingual educators typically interpret commonly used languages, like Spanish. However, because educators of Indigenous languages of Latin America are not common in schools, as Valeria explained, districts have come to rely on nonprofit organizations working with Indigenous migrant communities to find and mentor Indigenous interpreters. “Because I have to work with communities that are neither fluent in English nor Spanish, I have to recruit any interpreter available, whether they are accredited or certified, or have experience or not,” Valeria pointed out when discussing her role as a mentor of interpreters at a nonprofit organization in California.

Pain Point Three: Discrimination

Of the nine participants, five pointed out that discrimination has caused the marginalization and decline of Indigenous languages, arguing that discrimination is a palpable issue among Indigenous translators and interpreters.

Carlos, an engineering student who also works as a court interpreter and intercultural promoter, explained that racism has produced an intergenerational issue between the older generations who only speak an Indigenous language and the younger generations who only speak Spanish. He shared that in his community, “most of the town [elders], about 90%, speak an Indigenous language, Zapoteco. Adults suffer discrimination when they move to the city or work here and there.” Because of discrimination, Carlos tried not to speak his Zapoteco language at first: “When I was at school, I was embarrassed to speak it.” Carlos added:

Nowadays in [his] community, the majority are losing [the Zapoteco language], more so the kids, because their parents are teaching them Spanish, because of the same reason, parents don’t want their kids to suffer embarrassments or discrimination by other kids whose first language is Spanish when they arrived at the city.

As an interpreter, Carlos helps incarcerated Indigenous people navigate the legal system, and as an intercultural promoter, he teaches Zapoteco to the children in his community. He explained: “These are kids who are learning Spanish and are letting go of their Indigenous language.” He became an advocate “because the majority of the men in [his] town leave to the East or West Coast of the US.” Carlos helps his community and his culture through language.

Sadly, discrimination against Indigenous people is not a new problem. It has existed for a long time outside and inside Indigenous communities. Antonia, a Tarahumara court interpreter and the coordinator of a nonprofit organization that aims at training Tarahumara court interpreters, pointed out that discrimination is also deeply rooted in their Indigenous communities: “We have heard about human rights and about discrimination for a long time, and we are still talking about the same issues with no solutions. Sometimes there’s even discrimination among ourselves. What should we expect from those we aren’t of our race?” Although there have been efforts to combat this issue, discrimination continues to be one of the most critical problems affecting Indigenous people and thus Indigenous interpreters and translators.

Pain Point Four: Low and Irregular Wages

Low and irregular wages in the profession was another pain point that five of the nine participants identified. As Lourdes pointed out, this is a more pressing issue in Latin American countries like Mexico and Peru. Lourdes is a Professor of Translation, Interpreting, and Intercultural Studies and Indigenous rights advocate who often works as an international consultant in matters related to Indigenous rights. She explained that although Lima, the capital of Peru, is the home of some Indigenous communities, most Indigenous court interpreters live in rural communities far away from the capital and, therefore, interpreters have to commute to Lima for court hearings. Still, the Peruvian courts do not have a set budget for travel expenses and may or may not allocate funding for it:

[W]hat happens if the interpreter comes from a Peruvian Amazonian Achuar community and has to take first a boat of various hours of river journey to later arrive in Lima, and then take a plane [to the final destination]? Who pays for the travel expenses? Who pays for the transportation? The reimbursement isn’t clear. A plane ticket costs $150 US[D] minimum.

Although the courts in the US are financially equipped with standardized rates that remunerate the work of interpreters, the educational field in the US is not yet prepared to handle the influx of Indigenous immigrant children from Latin America. Some school districts in places where Indigenous migrant communities concentrate, like California, are increasingly trying to accommodate the needs of Indigenous families by funding in-house Indigenous interpreters. As Valeria pointed out, interpreters of Indigenous languages are not readily available because districts, like courts and medical facilities, also require interpreters and translators to have fluency in English and a high school diploma. Therefore, Valeria explained, organizations that work with Indigenous migrant communities, and sometimes the same districts, embark on a long process of finding people within an Indigenous community who can informally help as an interpreter and later be formally prepared.

Pain Point Five: Inconsistent Local Government Policies

Constant changes in local governments affect the work of Indigenous interpreters and translators both as practitioners and as advocates, as five of the nine participants pointed out. In Mexico, for instance, state governments change every six years, and each government brings a new cabinet and new policies. As a result, initiatives by one government are not always carried out by another, as Alejandro explained. He praised the Defender’s Office in Oaxaca for actively hiring more Indigenous defenders, but he worried that other incoming governments might not sustain this enthusiasm toward addressing Indigenous matters. “It is important what the Defender’s Office is doing” because “not all incoming governments have that perspective, and sometimes they abandon Indigenous topics,” Alejandro commented.

Even when laws remain unchanged, power shifts affect Indigenous interpreters and translators. “Sometimes this happens because they are temporary governments. Those who come in new arrive without knowing how to continue the work or the commitment that others made,” Antonia explained.

As the pain points show, each participant’s individual experience is inherently linked to the collective experience of their community, and the pain points are intrinsically linked to their contexts as Indigenous individuals, hence the importance of using the Indigenous method of testimonio in this study.

In the following section, I discuss important findings that surfaced through the testimonios of the participants.

DISCUSSION

In general, all Indigenous language mediators self-identify as Indigenous individuals because—unlike in the case of European language mediation, where non-Europeans often choose to learn a European language to become a language mediator—non-Indigenous people do not often choose to learn an Indigenous language to become a language mediator in such language. Most people who speak an Indigenous language learn it as part of an Indigenous community.

Testimonio mapping reveals important findings that can help improve the experiences of Indigenous language mediators, both as technical communicators and as users. A testimonio is an Indigenous method that requires analysis through a non-Western lens (Medina, 2018; Menchú, 1984; Smith, 2012). Although the sample size in this study is small (as testimonio methodologies often are), from an Indigenous lens, the results are as valid as a larger sample size because the collective voices interpolate each individual experience. From an Indigenous lens, each voice represents the collective experience of the Indigenous interpreters and translators in their communities. Though each experience presents unique differences, general (collective) similarities are also represented in the pain points, which validates the data’s generalizations. Namely, all participants expressed that Indigenous interpreters and translators—themselves and/or a group in their community—experience issues caused by a lack of awareness of Indigenous matters, loose professionalization systems, discrimination, low and irregular wages, and/or inconsistent local government policies. Additionally, for Indigenous individuals, speaking with a collective voice is not the same as speaking on behalf of a group. Each participant in this study, whether Indigenous or not, was speaking with the collective voice of a group because each belongs to and/or works with Indigenous communities.

Furthermore, whereas some Indigenous professionals work with written interpretations, as Magdalena exemplified, most work as oral interpreters because Indigenous languages are primarily oral languages. Digital technologies, however, are increasingly aiding Indigenous language mediators in engaging with written translation (Gonzales et al., 2022). As the results show, the context of the individuals’ community dictates the field in which they work. Most professionals work in the legal field because there is more need here, and their profession in this field is more regulated and remunerated. Like in the case of any other profession, wages in the interpretation and translation profession vary country by country. In places like Mexico and Peru, for example, where there is less funding and less accountability in following regulations about providing interpreting services for Indigenous users, interpreters are not often remunerated in the health and educational fields. Although there are more regulations and funding for language mediation in the health and educational fields in the US, Indigenous professionals do not often fit the requirements. Government initiatives are also regulated and remunerated, but fewer opportunities exist in this field.

Indigenous interpreters often work in various countries, and each country has different certification standards with complex requirements. Participants emphasized the importance of having consistent, measurable skills in the profession to impact the quality of the services provided and the status of the profession. Even within the complexities of working in a multidisciplinary, multilingual, multicultural, and multinational field by nature, Indigenous interpreters and translators argued that better standardizing systems to address their specific needs should exist across countries and professional fields. For example, U.S. courts do not have a top-tier certification for interpreters of Indigenous languages from Latin America, albeit the increasing numbers of Indigenous immigrants from Mexico and Central America who come across immigration courts.

Most participants agreed that lack of awareness about Indigenous matters causes many of the issues here addressed. Not understanding the lens of Indigenous language speakers and thus Indigenous interpreters can, and often does, provoke serious discrimination issues. For instance, not understanding desahogo and dialogue as Indigenous praxes causes unnecessary stress on both the Indigenous interpreter and the Indigenous individual for whom they provide the service.

As Alejandro explained, courts, especially U.S. courts, do not allow interpreters to have any communication with the Indigenous speaker outside the interpreting event. From the lens of Western courts, interpreters who engage in “side conversations” with Indigenous defendants during court hearings, even though these conversations are moments of desahogo, appear biased and thus unethical (Rivera, 2022). Chastising moments of desahogo during court hearings only provokes more stress on both the interpreter and the Indigenous defendant, as Claudia and Alejandro explained. Allowing a desahogo briefing before an interpreting event helps release some of the emotional burdens up front and gives the interpreter the context needed to perform a better interpretation, in the same way that non-Indigenous technical communicators need to know the exigence, context, audience, and purpose of a project before working on technical translations.

In the context of testimonio sharing during this study, the interactions during the roundtable produced a collective metatestimonio where the group built from one conversation after another until reaching a point of a collective desahogo that yielded the conscious feeling of “enough is enough” of the group. The cathartic moment of the metatestimonio of this group occurred right after most participants had shared their testimonios. At that point, Claudia expressed her discontent with the systems and proposed to act upon the written laws that have been created to protect Indigenous linguistic rights:

I believe that we, as actors, must demand more from wherever we are, in Chihuahua or Oaxaca. It is by acting, in any way, and by demanding what has already been written that we’ll get results [. . .].

Let’s begin by asking for a dignified wage [. . .] There’s the General Law of Linguistic Rights, why not use it to demand a budget for the payment of Indigenous interpreters and translators? I believe that we must continue to fight from our own trenches to implement and fulfill what has already been written.

Another issue related to a lack of awareness that the Indigenous practitioners brought up is how Spanish or English terms do not often have Indigenous equivalents that can be interpreted with one word or even one phrase. Many times, Indigenous interpreters draw on the Indigenous practice of dialogue to explain highly technical concepts, like “summary proceedings” or “affidavit of support” or “medical anesthesia,” as Lourdes pointed out. Then again, when interpreters engage in dialogue, as Alejandro explained, public officials often question the excessive amount of conversation in an interpretation that should have the same length as what was originally said to look objective through a Western lens.

Testimonio mapping also reveals important patterns about the civic engagement with which the participants engaged. Each participant engaged in activities that reflected their context. For example, younger professionals engaged in language revitalization projects that capitalize on new technologies, like creating videos to help Indigenous children become more fluent in their mother language. Conversely, seasoned professionals with more years of experience engaged in projects aimed at mentoring Indigenous interpreters and translators. Professionals with more access to resources (and to the English language as a resource), like academics and individuals working for nonprofits in the US, engaged in Indigenous rights activism. The one participant who engaged in written translation projects also came from an academic background.

As this study shows, the work of Indigenous interpreters and translators goes beyond language brokerage. Identifying the civic engagements of the participants helped increase their agency as Indigenous individuals navigating Western systems. The civic engagement activities identified also demonstrate that Indigenous professionals see their linguistic work as a service to their communities, understanding their profession as an act of activism. All in all, this study shows that Indigenous technical communicators are foremost community advocates with agency.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTITIONERS

Utilizing circumscribed UX methods that include concepts foreign to the contexts of underrepresented communities may hinder the communication during a research project and the trust between the participants and the researcher(s). Therefore, testimonios can be a valuable tool to design UX projects with Indigenous individuals and other underrepresented groups who express their needs as collective needs. Testimonios intrinsically examine a user’s experience in the social and cultural context of a group while revealing the user’s civic engagement and call to action through a narrative, increasing user agency and supporting user advocacy. This method works well with superdiversified groups with different perspectives as it helps practitioners understand important cultural differences when grounding research on cultural contexts. When conducting research with Indigenous groups, specifically, researchers must consider the community-oriented roles of Indigenous individuals. Each participant’s personal and collective narratives and the dialogue embedded in these narratives allow participants to reflect on issues at a deeper level, engaging with their unique differences while revealing general similarities.

To work with testimonios as a methodology, however, practitioners must invest time to build a relationship with the participants. It is not a methodology that can be done through impersonal modes (like email). Researchers must work with participants in person or through a digital video conferencing tool that allows participants to interact with researchers and with one another. Most importantly, practitioners must understand this methodology from an Indigenous lens (Medina, 2018; Menchú, 1984; Smith, 2012), especially when working with the unique elements of desahogo and dialogue. From a Western lens, a narrative from a collective voice might seem out of place; a dialogical approach to research where researchers get involved in the conversations might seem biased; and an oral cathartic release of emotion in highly technical environments often seems unprofessional. From an Indigenous lens, however, the collective voice of a narrative points out the social and cultural roots and effects of complex issues; a dialogical approach engages participants in a deep reflection and helps negotiate meaning in oral interactions, balancing the relationships of power in research; and an emotional desahogo leads participants to a call to action that empowers users during a research project.

In short, with the help of the multidimensional nature of testimonios, UX researchers can create better research experiences for Indigenous individuals and individuals who are part of other underrepresented groups. Testimonios can help localize, or adapt to a specific context, the design of content, products, and processes in a way that better aligns with the different contexts and experiences of Indigenous groups and other diverse groups. The testimonio approach in this study proves to be ideal for working with Indigenous individuals in a multicultural setting, ultimately revealing that Indigenous interpreters and translators, as technical communicators, are foremost community activists with agency.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Nora K. Rivera is an assistant professor at Chapman University, where she teaches rhetoric, composition, and technical communication courses. Her dissertation, The Rhetorical Mediator: Understanding Agency in Indigenous Translation and Interpretation through Indigenous Approaches to UX, received the 2022 Outstanding Dissertation Award by the American Association of Hispanics in Higher Education (AAHHE), the 2022 Honorable Mention Award by the Latin American Studies Association (LASA), and the Graduate School Outstanding Dissertation Award by the College of Liberal Arts at UT El Paso, her PhD-granting institution. Rivera’s research centers on Latinx and Indigenous rhetorics and their intersections with technical and professional communication. Her multidisciplinary work has been published in College Composition and Communication, the Chicana/Latina Studies Journal of Mujeres Activas en Letras y Cambio (MALCS), Programmatic Perspectives, the Journal of Teaching Writing, and intermezzo. Her forthcoming monograph, The Rhetorical Mediator, will be published by the Utah State University Press. Dr. Rivera can be reached at nrivera@chapman.edu.

References

Alonso, I., & Payás, G. (2008). Sobre alfaqueques y nahuatlalos: Nuevas aportaciones a la historia de la interpretación. [On alfaqueques and nahuatlatos: New contributions to the history of interpretation]. In C. Valero-Garcés, C. Pena & R. Gutiérrez (Eds.), Investigación y práctica en traducción e interpretación en los servicios públicos: Desafíos y alianzas [Research and practice in translation and interpretation in public services: Challenges and alliances] (pp. 38–51). Universidad de Alcalá.

Benmayor, R. (2012). Digital testimonio as a signature pedagogy for Latin@ studies. Equity & Excellence in Education, 45(3), 507–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2012.698180

Campbell, L., & Mithun, M. (1998). Native American languages. Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia. Microsoft.

Cardinal, A. (2022). Superdiversity: An audience analysis praxis for enacting social justice in technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2022.2056637

Delgado, D., Burciaga, R., & Flores J. (2012). Chicana/Latina testimonios: Mapping the methodological, pedagogical, and political. Equity & Excellence in Education, 45(3), 363–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2012.698149

Gonzales, L., Leon, K., & Shivers-McNair, A. (2020). Testimonios from faculty developing technical & professional writing programs at Hispanic-serving institutions. Programmatic Perspectives, 11(2), 67–93.

Gonzales, L., Lewy, R., Hernández Cuevas, E., & González Ajiataz, V. L. (2022). (Re)designing technical documentation about COVID-19 with and for Indigenous communities in Gainesville, Florida, Oaxaca de Juárez, Mexico, and Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 65(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2022.3140568

INALI. (2008). Catálogo de las Lenguas Indígenas Nacionales. [Catalogue of National Indigenous Languages.] Diario Oficial de la Federación.

Kovach, M. (2010). Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts. University of Toronto Press.

León-Portilla, M. (1991). Huehuehtlahtolli: Testimonios de la antigua palabra. [Huehuehtlahtolli: Testimonios of the ancient Word.] Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Macri, M. J. (2005). Nahua loan words from the early classic period: Words for cacao preparation on a Río Azul ceramic vessel. Ancient Mesoamerica, 16(2), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536105050200

Medina, C. (2018). Digital Latin@ storytelling: Testimonio as multi-modal resistance. In C. Medina & O. Pimentel (Eds.), Racial shorthand: Coded discrimination contested in social media. Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press. http://ccdigitalpress.org/book/shorthand/chapter_medina.html

Menchú, R. (1984). I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian woman in Guatemala (E. Burgos-Debray, Ed.; A. Wright, Trans.). Verso.

Mora Curriao, M. (2007). La construcción de sí mismo en testimonios de dos indígenas contemporáneos. [The construction of the self in the testimonios of two contemporary Indigenous people.] Documentos lingüísticos y literarios, (30). http://www.revistadll.cl/index.php/revistadll/article/view/214

Phillips, L. L, & Deleon, R. L. (2022). Living testimonios: How Latinx graduate students persist and enact social justice within higher education. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 65(1), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2022.3140569

Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power and Eurocentrism in Latin America. International Sociology, 15(2), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580900015002005

Rivera Cusicanqui, S. (1987). El potencial epistemológico y teórico de la historia oral: de la lógica instrumental a la descolonización de la historia. [The epistemological and theoretical potential of oral history: from instrumental logic to the decolonization of history.] Temas Sociales, 11, 49–64.

Rivera, N. K. (2022). Managing Indigenous language interpretation and translation services in the public sector. In A. Castellanos García, L. Gonzales, C. V. Kleinert, T. López Sarabia, E. Matías Juan, M. Morales-Good, & N.K. Rivera (Eds). Indigenous Language Interpreters and Translators: Toward the Full Enactment of all Language Rights. Enculturation Intermezzo. https://intermezzo.enculturation.net/16-gonzales-et-al.htm?fbclid=IwAR3-4coyNo_i1M-wP3td4vX08LSPiTmpCBrU5cUmPyp93RhwFqVyfcnW-YM

Rivera, N. K., & Gonzales, L. (2021). Community engagement in TPC programs during times of crises: Embracing Chicana and Latina feminist practices. Programmatic Perspectives, 12(2), 39–65.

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Zed.

Stanford University d.School. (2020). About. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from https://dschool.stanford.edu/about.

Sun, H. (2012). Cross-cultural technology design: Crafting culture-sensitive technology for local users. Oxford University Press.

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2018). Toward what justice? Describing diverse dreams of justice in education. Routledge.

UN Commission on Human Rights. (1982). Report of the sub-commission on prevention of discrimination and protection of minorities on its 34th session: Study of the problem of discrimination against indigenous populations. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/publications/2014/09/martinez-cobo-study/.

Vespa, J., Armstrong, D. M., & Medina, L. (2020). Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060 [Report]. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.html.

Wible, S. (2020). Using design thinking to teach creative problem solving in writing courses. College Composition & Communication, 71(3), 399–425.