doi.org/10.55177/tc454765

By Hui-Fang Shang

Abstract

Purpose: The incorporation of computer-mediated communication (CMC) has been widely used in recent English as a foreign language (EFL) teaching and learning due to the rapid advancement of technology. Despite the prevalence of online CMC communications, previous research has yielded mixed results, and empirical evidence on how online communications affect student reading comprehension is limited. This study compares the effects of online asynchronous and synchronous communications on EFL reading comprehension in a Taiwanese collaborative learning context.

Method: Ten reading comprehension tests and an online questionnaire survey were administered to 100 university students enrolled in two senior reading classes in Southern Taiwan. Independent-sample t-tests, descriptive statistics, and Pearson product-moment correlation analyses were computed to investigate the differences and relationships between perceived asynchronous and synchronous communication use on EFL reading comprehension performance.

Results: The findings revealed that participants used the synchronous communication mode more frequently than the asynchronous mode. The reading score obtained through the synchronous group was slightly higher than that obtained through the asynchronous group; no statistically significant difference was found. As students practiced more in asynchronous and synchronous communication modes, their reading comprehension ability improved significantly.

Conclusion: Although learners generally accept both online communication modes, the open-ended question results reveal several disadvantages and advantages of online communication environments. The study’s limitations, as well as the implications for instructional pedagogy and future research, are presented and discussed.

Keywords: Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC), Asynchronous Communication, Synchronous Communication, EFL Reading Comprehension

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Taiwanese English as a foreign language (EFL) students use the synchronous communication mode more frequently than asynchronous mode. This might have implications for technical communication pedagogy, especially as it related to EFL students.

- When teaching Taiwanese EFL students, technical communication instructors should consider that synchronous groups have better perceptions of computer-mediated communication than the asynchronous groups.

- Both mode (synchronous and asynchronous) appear to be equally effective in improving EFL reading comprehension.

Research on reading has shown that reading exists as a complex cognitive activity required for adequate functioning and information acquisition in modern society (Alfassi, 2004). In some countries, reading English as a foreign language (EFL) efficiently and effectively is the most important and critical skill that influences university students’ success in their future careers (Koda & Zehler, 2008). The common justification is that comprehension of English text is an important tool for obtaining information on a wide range of topics (Pan, 2010). However, Taiwanese EFL students’ reading comprehension remains poor; not all readers have the essential knowledge and experience to relate to the text (Chen et al., 2011).

Previous research indicates that in peer communication environments, EFL students can learn not only a language but also knowledge about various subject matters (Zhang et al., 2016). Peer communication enables language learners to collaborate while also improving their grammar, reading comprehension, and problem-solving abilities (Zhang, Anderson, & Nguyen-Jahiel, 2013). With the rapid advancement of technology, the incorporation of computer-mediated communication (CMC) has become increasingly common in recent EFL teaching and learning. CMC, also known as computer-assisted class discussion (CACD) or computer-mediated discussion (CMD), can effectively provide learners with opportunities to practice their foreign language while communicating with peers, either immediately or at a specific time, overcoming traditional time and space constraints (Tsuei, 2011; Yuan & Kim, 2018). According to previous research (Al-Jabri, 2012; Chen, 2013; Gikandi & Morrow, 2016; Hsieh & Ji, 2013; Jong et al., 2014; Lage, 2008; Rezaee & Ahmadzadeh, 2012), CMC can be divided into two communication modes. The first mode is asynchronous or delayed-time communication via email, blogs, Moodle (a modular object-oriented dynamic learning environment), and other education-based bulletin boards. The second mode is synchronous or real-time communication via WeChat, Facebook, and/or audio/video conferencing. EFL learners can easily communicate with other learners synchronously (i.e., all users are logged on and discuss simultaneously) or asynchronously (i.e., learners do not discuss in a real-time environment) using CMC and the internet.

Previous research has demonstrated that online collaborative asynchronous and synchronous communications can provide authentic peer communication while also assisting students in improving their reading comprehension (Hsieh & Ji, 2013). In other words, online communication requires learners to share ideas with peers, which improves reading comprehension (Cummins, 2008). According to Lu and Chiou (2010), online peer communications provide a collaborative environment to promote students’ online participation in language learning by using technology and tools such as discussion boards, allowing learners to collaborate in learning development. Goggins and Xing (2016) suggests that a structured online peer communication forum, typically a text-based environment, could assist students in effectively learning course content. This type of collaborative learning allows students to share their ideas in public regardless of time or location (Vonderwell & Zachariah, 2005), reflect on them (Hewitt, 2005), facilitate knowledge acquisition, and improve academic outcomes (Goggins & Xing, 2016).

However, research has shown that using CMC in a language learning context does not always promote learner enhancement and reading comprehension due to negative perceptions or low motivation (Palvia & Palvia, 2007; Sistelos, 2008). Al-Jarf (2005), for example, demonstrated that students might have negative perceptions of online intervention because they are unfamiliar with online tools or believe that online learning is similar to chatting online with friends. Furthermore, there have been debates over whether online asynchronous or synchronous learning modes are more effective (Palvia & Palvia, 2007; Sistelos, 2008). Chen, Klein, and Minor (2008) discovered that using asynchronous peer discussions twice a week effectively meets communication needs in online learning. Learners can communicate with their peers at various times and locations based on their schedules and convenience. The disadvantage of asynchronous communication is that participants must wait longer for a peer’s response, which may reduce motivation and engagement (Ashley, 2003). According to Stephens and Mottet (2008), the benefits of using synchronous learning environments include real-time knowledge sharing and immediate access to ask questions and receive answers from peers. However, because participants must attend sessions in designated rooms simultaneously, this type of synchronous environment may lack flexibility (Skylar, 2009).

Purpose of Study

Most research studies on collaborative peer discussion in the EFL reading context are conducted in a traditional face-to-face setting (Zhang & Zhu, 2017). Despite the prevalence of online communication, few studies have been conducted to investigate the impact of various modes of online discussion on the reading achievement of Taiwanese EFL university students (Goggins & Xing, 2016). As a result, it is critical to investigate whether increased use of the CMC learning approach positively affects students’ English reading performance. As previously stated, research on the effects of asynchronous and synchronous CMC applications on EFL teaching and learning yielded inconclusive results, necessitating a comparison of the two modes and their impact on Taiwanese EFL reading comprehension (Hsieh & Ji, 2013; Skylar, 2009). This research aims to learn more about the effectiveness and relationship of these two online collaborative CMC modes on EFL reading performance. Three research questions are addressed based on the aim of this study:

- How do asynchronous and synchronous communication interventions differ regarding EFL reading comprehension?

- Does the frequency students participate in asynchronous and synchronous communications correlate with their reading comprehension scores?

- What are the participants’ perspectives on the efficacy and drawbacks of asynchronous and synchronous communication modes used in this study?

The study’s findings will provide insight about what happens in online peer CMC environments for EFL teachers and curriculum designers. It also recommends that instructors consider balancing the use of different CMC modes, not only to increase students’ motivation in collaborative peer learning environment but also to satisfy individual preferences and needs by understanding the benefits and drawbacks of using online CMC modes.

Literature Review

Asynchronous Communication

Asynchronous communication is a type in which learners can discuss with their peers by posting messages for mutual reflections and comments to produce more syntactically complex language and more words (Paulus, 2007; Rezaee & Ahmadzadeh, 2012; Zapata & Sagarra, 2007). Furthermore, because there is no pressure of real-time discussion, asynchronous communication creates a less stressful learning environment for shy and anxious students, with more participation and motivation (Shadiev et al., 2015; Shadiev et al., 2018). Li et al. (2018) investigated the relationship between asynchronous communication and course satisfaction in China, using 11 platforms, 321 courses, and over 13,000 ratings. According to the findings, asynchronous communication can significantly predict learner satisfaction. Science and technology courses, in particular, have a significantly different slope than humanities courses. Kent, Laslo, and Rafaeli (2016) used Ligilo as an online communication platform to study 231 students in eight classes from four universities. The study investigated the role of interactivity as a process of knowledge construction in asynchronous communication and its relationship to learning outcomes. According to the study’s findings, asynchronous communication plays a vital role in predicting satisfaction and learning outcomes; the students who created the semantic network structured the discussion, implying a relationship between communication structuring and learning outcome.

Goggins and Xing (2016) proposed two asynchronous communication models and investigated potential factors and their impact on learning. According to the findings, the number of posts written by students significantly correlates with their learning performance. Furthermore, the less time a student takes to respond to other people’s posts or the more time a student spends reading, the better the student’s learning performance. Carroll (2011) discovered that the disadvantage of asynchronous communication is that participants must wait longer for the returned feedback, which may reduce learners’ engagement in the asynchronous task. Furthermore, Watson, McIntyre, and McArthur (2010) stated that students’ lack of facial expressions and body language in asynchronous communication might lead to misinterpretation, mainly if they are in a “high-pressure discussion or teamwork situation” (p. 24). Given the mixed results of previous studies and the scarcity of empirical research on reading outcomes, more attention should be paid to specific disciplines in the EFL reading context when monitoring asynchronous communication in English.

Synchronous Communication

Another type of CMC communication is synchronous communication, which requires both the sender and receiver of the message to be logged on simultaneously to communicate with each other (Kosalka, 2011). Participants in synchronous communication can construct more complex sentences, and it is an excellent medium for EFL learners to ask more questions and spend more time interacting with their peers in order to improve their interaction skills and communicative competence (O’Rourle & Stickler, 2017). Tsuei (2011) investigated the effects of synchronous peer-assisted learning on developing reading skills, peer interaction, and self-concept in 56 fourth-grade students (aged 10-11 years) from two classes at an elementary school in Taiwan. Regarding Chinese reading skills, the research findings revealed that students in the synchronous peer-assisted learning group outperformed those in the face-to-face group. Those studies conclude that synchronous activity significantly influences online peer interactions, which results in significant growth in the reading skills and self-concept of passive learners.

Al-Jarf (2014) investigated Elluminate Live, a web-conferencing software, as a synchronous supplementary reading comprehension practice. An experimental group of 25 students was randomly assigned to synchronous Elluminate Live reading practice sessions from home. In comparison, a control group of 24 students was assigned to face-to-face reading practice sessions in a classroom. The findings revealed a statistically significant difference in reading enhancement between the experimental and control groups. Furthermore, compared to the control group, the experimental group develops more positive attitudes toward synchronous communication and reading practices because synchronous web-conferencing creates a warm environment in which students receive more practice and immediate feedback from peers to resolve problems as soon as possible. As a result, synchronous web-conferencing software was deemed an effective tool for providing students with practical reading guidance.

McBrien, Jones, and Cheng (2009) investigated participants’ satisfaction with three undergraduate and three graduate courses using the synchronous online learning mode. The findings of this study revealed that, while students are satisfied with the use of the synchronous online platform, they believe that a lack of in-person nonverbal sub-communication could lead to confusion among students. The study also discovered that technical difficulties influence students’ perceptions of synchronous learning environments. Ng (2007) investigated the effectiveness of a synchronous e-learning system (Interwise) for online tutoring by interviewing six tutors and eight students. According to the findings, students and tutors were pleased with Interwise for online tutoring, and the peer interaction on this platform was deemed successful. Nonetheless, several students reported that technical difficulties could detract from their overall positive learning experience. Because there was conflicting evidence that synchronous peer communication produces positive outcomes, it is critical to assess the impact of EFL students’ learning through synchronous communication tools.

Asynchronous and Synchronous Communications in EFL Learning

Numerous studies on the impact of asynchronous and synchronous communications on EFL academic performance have yielded inconclusive results. Hirotani (2006), for example, investigated the effect of synchronous and asynchronous CMC on improving oral proficiency among Japanese learners. Students preferred face-to-face communication over the other two modes, but synchronous CMC helped them achieve higher oral syntactic complexity than asynchronous CMC. Moreover, Al-Jabri (2012) conducted a study to investigate how online synchronous and asynchronous course formats influenced the academic development of 82 undergraduate students. The findings revealed no significant difference in the enhancement of grade level and English proficiency level between these two online course formats, although students could learn new materials through communication with others. Furthermore, students prefer the online synchronous format over the asynchronous format because it provides a more flexible and interactive learning environment. Skylar (2009) compared the performance and satisfaction of 44 preservice general education and special education students who participated in a hybrid course that used online asynchronous and synchronous learning environments. According to the findings, both types of lectures were effective in delivering online instructions. Nonetheless, most students stated that they would prefer synchronous learning over asynchronous learning because the former allows for more interactivity, and the learners’ satisfaction with using technology improved.

In addition, Chau (2017) compared student interactions in synchronous versus asynchronous CMC systems. The findings revealed that synchronous interactions account for more social-emotional interactions than asynchronous ones. Students spent more time in task-oriented interaction during asynchronous communication than in synchronous communication. Students who followed the student-centered communication guidelines were able to encourage full participation in an online seminar. In a quasi-experimental study, Hsieh and Ji (2013) investigated the effectiveness of computer-mediated synchronous and asynchronous communication forums in reading comprehension performance with 138 non-English college majors in Taiwan. Pre- and post-reading comprehension tests and a post-perception survey were used as research instruments. The findings showed no significant difference in reading posttest scores between the synchronous and asynchronous groups. The perception survey results also revealed no significant difference between the two groups. Nevertheless, both groups express similar positive attitudes toward aspects of CMC collaboration and CMC effects, which are effective in supporting improvement in reading posttest scores.

Despite the prevalence of online CMC, research on online communication has focused on issues such as learner completion rates, learner satisfaction, and differences between online and face-to-face learning (Goggins & Xing, 2016). To our knowledge, only a few studies have focused on the impact of asynchronous and synchronous communications on EFL reading ability. Furthermore, previous research has yielded mixed findings regarding the effect of online communication on student learning (O’Rourke & Stickler, 2017). For example, Cheng et al. (2011) discovered a significant relationship between student final grades in an online class and the number of discussion board postings made by students during the intervention. In other studies, students reported that discussion board postings add little value to their understanding of the course content (Reisetter & Boris, 2004). Given the time and effort required to create and maintain the online discussion board, it is critical to continue testing its value to student learning, such as using online peer communication modes effectively and improving students’ reading performance in such collaborative learning environments.

Methods

Participants

This research was carried out throughout an 18-week senior reading course for English majors at a private university in Southern Taiwan. In spring 2019, students in this required course, Reading Seminar, met once a week for two hours. The primary goal of this course is to help students develop effective reading skills and the clear thinking required for more advanced reading comprehension. There were 100 seniors in total, with 34 males and 66 females. The students’ ages ranged from 20 to 24, with a mean of 22.61 years (SD =.788). All participants were enrolled in two classes of the required English reading course taught by the same instructor (who was also the researcher). The researcher assigned class A (n = 50) to the asynchronous group and class B (n = 50) to the synchronous group randomly. All participants were required to take the online simulated TOEIC (an English communication skills test) at the start of the 2020 spring semester to ensure that these two groups had comparable levels of reading proficiency. Only the reading section score was taken into account for this study. The students had 75 minutes to answer 100 questions (the maximum reading score is 495 points). The asynchronous and synchronous groups’ mean scores were 243.13 (SD = 64.95) and 199.29 (SD = 74.90), respectively, with no statistically significant difference between these two groups (F = .971, p = .327 > .05). This finding revealed that students in both groups had comparable levels of reading proficiency prior to online CMC interventions.

Instruments

Material

This study used 10 expository texts (approximately 1000 words each) from the book Ten Steps to Improving College Reading Skills (Langan, 2005). The book presents ten reading skills widely recognized as essential for basic and advanced comprehension, such as understanding vocabulary in context, recognizing main ideas, identifying supporting details, making inferences, identifying an author’s purpose and opinions, and evaluating arguments. The texts were chosen and given to the participants based on several criteria. They included real-world newspaper and magazine articles about job interviews, computer cultures, solar storms, travel adventures, other topics, and practice exercises.

Reading comprehension tests

Both groups were given a 10-item multiple-choice test to assess their comprehension of the reading material. Each test was designed to correspond to a reading article from the book Ten Steps to Improving College Reading Skills (Langan, 2005). Ten reading comprehension tests were used to estimate students’ reading comprehension, with a maximum score of 10 for each test. To assess content validity, two English instructors from the research site’s Department of Applied English were asked to revise the test items to make them more appropriate and content based. A pilot study with four students from a similar-level class was conducted to ensure that each item was fully understandable.

Asynchronous communication tool

This reading course used Moodle as the web-based media for asynchronous peer communication. Moodle is a free and open-source software platform for managing e-learning websites and applications (Moodle, 2007). According to Hsieh and Ji (2013), Moodle has the potential to engage students in active and collaborative communications outside of the classroom, resulting in an effective learning environment. As a result, Moodle was made available for free at the research site and was chosen as the asynchronous mode platform for online peer communication.

Synchronous communication tool

This study used WeChat as the synchronous communication tool for instant message communication. According to Guo and Wang (2018), the WeChat platform pushes reading materials to English majors, and their study discovered the efficacy of this mode of learning, including students’ improved reading ability and facilitated technical communication among WeChat groups as an academic field in China (Ding, 2019). Lin, Qin, and Guo (2016) also discovered that WeChat-supported learning could improve college students’ self-efficacy in English learning. As a result, after reading articles assigned by the instructor, the synchronous group used WeChat as a virtual community to post words, start online instant communications, ask and answer questions, share information and knowledge, and develop a reading comprehension activity.

Online questionnaire

Hsieh and Ji’s (2013) questionnaire was used to elicit students’ perceptions of the effectiveness and shortcomings of online peer communication modes. The online questionnaire included 28 items measuring two broad categories: asynchronous communication via Moodle (14 items) and synchronous communication via WeChat (14 items). Four students were randomly chosen to conduct a pilot study to ensure that each item was fully understandable. Cronbach’s alpha was also calculated to assess the dependability of the asynchronous and synchronous questionnaire items. The overall alpha value for the questionnaire items was .866. The reported reliabilities for each subsection were .871 for asynchronous communication and .855 for synchronous communication. These findings supported the hypothesis that the questionnaire survey was reliable for assessing asynchronous and synchronous communications in EFL reading. One open-ended question was proposed to elicit participants’ perspectives on the benefits and drawbacks of online communication tools to improve their reading ability.

Data Collection Procedures

Both groups of students were divided into 12 groups of four to five people. Students were allowed to choose their group members to avoid potential stress from working with peers they did not know well (Hu, 2005). Participants were required to read 10 articles assigned by the instructor (one per week) without any formal instruction. The goal of this exercise was to get students used to asking their peers questions if they did not fully understand the articles’ content. Another reason for doing this online CMC task was that most students did not have many required courses in their senior year and thus had few opportunities for face-to-face discussions.

After completing each CMC reading task, all participants were given a written comprehension test prior to their regular class meeting. The instructor electronically joined each group discussion to be aware of students’ exchanges and, if necessary, to correct any misleading messages during the entire online reading task communication process. A series of trainings for reading skills, peer communication, and asynchronous and synchronous communications were administered to improve the effectiveness of the CMC tasks.

Training for reading skills

As previously stated, the book Ten Steps to Improving College Reading Skills (Langan, 2005) was used in this study because it employs a series of trainings to help students carefully consider basic content and thus strengthen their understanding of the selected articles. The instructor first focused on the six basic skills involving the more literal levels of comprehension to help students develop effective reading and clear thinking, such as understanding vocabulary in context, recognizing main ideas, identifying supporting details, and understanding examples-based relationships. The remaining skills covered more advanced critical levels of comprehension, such as differentiating between facts and opinions, making inferences, determining an author’s purpose and tone, and evaluating arguments. In a nutshell, this course aims to teach students key reading skills that will help them become better independent readers and thinkers.

Training for peer communication

The use of scaffolded reading among peers has demonstrated higher-level achievement in EFL reading to facilitate the goal of helping students read more productively and gain a fuller understanding of the text (Fitzgerald & Graves, 2005). As a result, the instructor must train students on how to improve their understanding skills through peer communication. Following an explanation of reading skills, the instructor presented an article, asked a text-based question, and then guided students on how to use multiple reading strategies such as understanding vocabulary, predicting reading content, identifying and skimming for main ideas, scanning for information, and drawing conclusions about the correct answer. The instructor then asked each student to pose three text-based questions and discuss them with their group members to find correct answers. The questions could be ones that the participants did not understand or ones that they asked to make their peers think deeply. The main goal was to encourage students to verbalize their thoughts and interact with their peers to arrive at a satisfactory answer. The goal was for students to benefit from peer interaction rather than teacher interaction. However, if peer communication became confusing or ineffective, the instructor was required to step in.

Training for asynchronous communication

After becoming acquainted with the peer communication process, students had to complete 10 asynchronous peer communication tasks after reading 10 assigned articles before the next class meeting. The articles were posted in Moodle’s discussion section, which also served as an asynchronous platform for peer communication. For each asynchronous communication task, students had to log into Moodle with their usernames and passwords and collaborate with four to five group members. Students in the asynchronous group were required to read the assigned articles and respond to three text-based questions from the course materials or outside-of-class answers. Peers were then required to respond to the questions at least twice a week to meet the needs for effective communication and interventions in asynchronous learning (Chen et al., 2008). The number of message exchanges by individual students was later collected to track students’ frequency of participation in the asynchronous communication activity.

Training for synchronous communication

Students in the synchronous group were required to register using their real names and student IDs and to join a WeChat group of four to five members to receive instructions on how to use the WeChat platform and collect feedback from their peers. WeChat was used specifically as a platform to provide 10 articles (the same as the asynchronous group) for students to use in synchronous peer communication. Students were required to post three text-based questions from the course materials or answers from outside the class at least twice per week. The instructor would log in to the students’ WeChat platform at least twice weekly to monitor synchronous communications. The number of message exchanges by individual students was also recorded later.

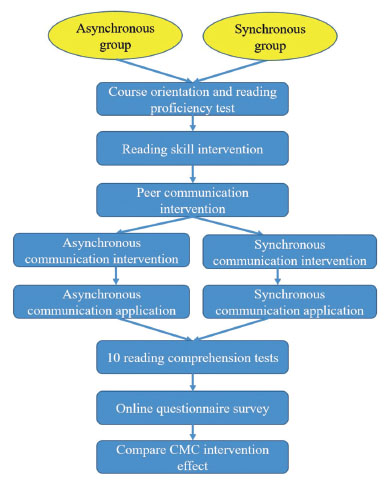

At the end of the study, an online questionnaire survey was used to collect participants’ perceptions about using asynchronous and synchronous communication tools to improve their reading comprehension performance. Figure 1 depicts an overview of the instructional design.

Data Analysis

To answer the first research question, independent-sample t-tests were used to see if there was a significant difference in the number of message exchanges and comprehension test scores when the asynchronous and synchronous communication modes were used. Pearson product-moment correlation analyses were performed for the second research question, which sought to identify the nature of the relationships between perceived asynchronous and synchronous communication use in the online questionnaire survey on English reading comprehension performance. Finally, descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and frequency) were computed to investigate the perceptions of participants in the English reading course of the online communication applications.

Results

Differences and Frequency of Asynchronous and Synchronous Communications on Reading Scores

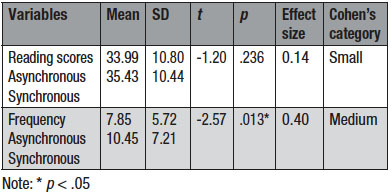

Independent-sample t-tests were used to see if there was a difference in comprehension test scores and the number of message exchanges between asynchronous and synchronous communication modes. As shown in Table 1, the mean of the reading score obtained through the synchronous intervention (M=35.43, SD=10.44) was higher than that obtained through the asynchronous intervention (M=33.99, SD=10.80); however, the difference was not statistically significant (p= .236). According to this result, there was no difference in reading comprehension scores after synchronous and asynchronous interventions. Because the sample size was small, Cohen’s d was used to calculate the effect size to increase the test’s practical difference (Wilson Van Voorhis & Morgan, 2007). The effect sizes for reading scores were 0.14 based on the computation results (a small difference). Regarding the frequency of asynchronous and synchronous communication applications, there appears to be a significantly greater frequency difference between the synchronous intervention (M=10.45, SD=7.21) and the asynchronous intervention (M=7.85, SD=5.72), indicating that students used WeChat more frequently than Moodle while performing online CMC tasks. The effect size for the number of message exchanges was 0.40. It is concluded that students used synchronous communication mode more frequently than asynchronous mode, with a medium difference.

Relationships between Asynchronous and Synchronous Communications on Reading Comprehension

To address the relationship between asynchronous and synchronous groups in the communication modes on reading comprehension performance, Pearson correlation coefficients were computed among the frequency of Moodle, and WeChat communication use and reading mean scores. First, the results revealed a significantly positive correlation between reading scores and the frequency of Moodle communication (r = .61, r2 = 37%, p = .000). Thus, it is suggested that with increased asynchronous communications, students’ reading comprehension scores via Moodle use increased as well. Regarding the students’ synchronous communication, the results indicated a significant correlation between reading scores and the frequency of WeChat communication (r = .40, r2 = 16%, p = .004). As such, it is worth noting that as students increased their message exchanges through synchronous communication, their reading scores also increased.

Students’ Perceptions of the Effectiveness of Asynchronous and Synchronous Communication Use

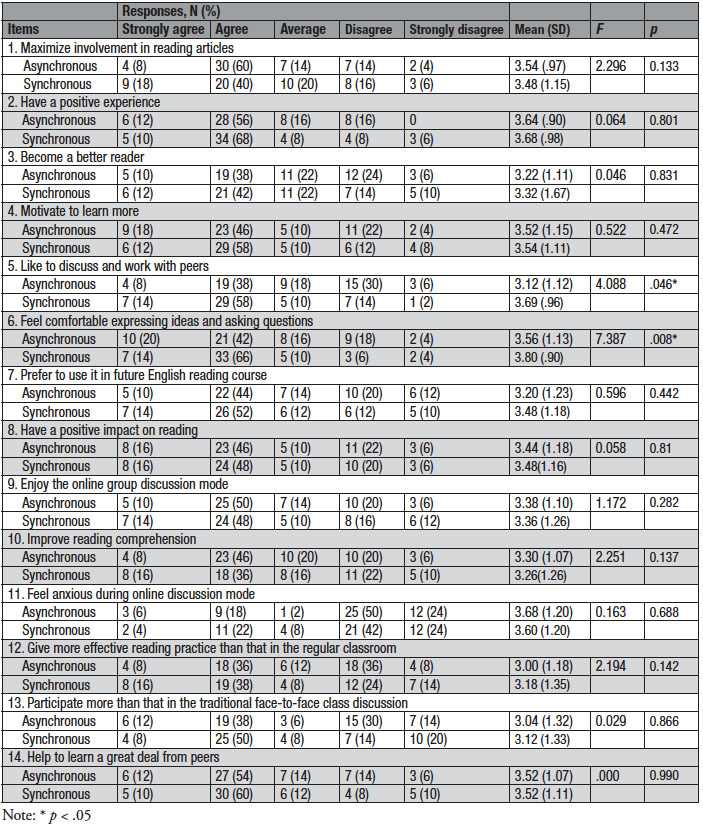

To thoroughly compare students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of asynchronous and synchronous communications, their online communication conditions from the questionnaire survey should be carefully examined. As shown in Table 2, both groups of students agreed that CMC fostered a learning environment that assisted them in engaging in social interchange with peers and improved their reading comprehension. It is especially intriguing to note that there were two significant differences between these two groups on items 5 (p= .046) and 6 (p= .008). Most synchronous participants (72%) outnumbered the asynchronous participants (46%) in terms of preferring to discuss and work with peers. Furthermore, synchronous participants (80%) felt more at ease expressing ideas and asking questions than asynchronous participants (62%). Nevertheless, when asked to compare reading practice in the regular classroom (item 12) and traditional face-to-face communication (item 13) to online communication modes, approximately 40% of participants in both groups disagreed that such a CMC mode could provide greater effectiveness than those in the conventional learning mode.

The open-ended question was thoroughly analyzed to better understand the participants’ perceptions of the benefits and drawbacks of using the CMC approach. Concerning the impact of asynchronous use, students provided numerous positive responses about using Moodle to improve their reading ability, as it provided a virtual environment to host communicative functions. “I enjoyed the online communication through Moodle because it helped me understand the text better and take tests with higher scores,” one participant said. Furthermore, participants might take longer to write personal comments and express ideas, reducing anxiety caused by time constraints. In other words, students felt more at ease because they could take their time considering their responses. Some students, however, reported that such asynchronous communication slowed communication because senders might not receive messages immediately as they would with email. They were frustrated because they did not receive a notification when information was posted. Some students also complained about having to sign in with their username and password every time they visited Moodle.

With regard to participants in the synchronous group, they frequently expressed the convenience and ease of online peer communication using synchronous communication. Such communication provided a strong sense of immediacy, and students reported that they were more likely to pay attention in this online community. They interacted with their peers more and asked more questions, improving reading comprehension. One participant stated, “I could improve my reading comprehension ability through the feedback and comments received from my peers because I learned the content knowledge through communications with others or having peers explain something to me.” Few participants, however, stated that their different learning rates made it difficult to share ideas on course materials. “Many of my group members did not prepare well and shared little course content, so I lacked [the] motivation to discuss with them,” one student said. Furthermore, some participants complained that it took too long to receive their peer’s returned messages or that they received no messages. They wondered if face-to-face communication would be preferable for more immediate communication.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study aimed to compare how asynchronous and synchronous communications affected students’ reading comprehension ability in Taiwanese CMC learning environments. The research results reveal several noticeable findings for CMC applications.

First, the difference in EFL reading scores between asynchronous and synchronous communication interventions revealed that the mean score obtained through the synchronous group was slightly higher than that obtained through the asynchronous group; no statistically significant difference, however, was found. This finding supports the findings of Al-Jabri (2012) and Hsieh and Ji (2013), who found no significant difference in reading scores between the synchronous and asynchronous interventions. Both modes of communication appear to be equally effective in improving reading comprehension. Despite this, a significant difference in the frequency of asynchronous and synchronous communication applications was observed, showing that students participated in synchronous communications more frequently than asynchronous communications. Although this study finds no direct relationship between preference and frequency of the two online communication modes, Skylar’s (2009) findings suggest that students prefer synchronous learning over asynchronous learning because the former allows for more interactivity and immediate feedback.

Second, the finding indicates that increased asynchronous communications may help students develop significant and positive relationships in improving their reading scores via Moodle. This finding is consistent with previous research, such as that of Li et al. (2018) and Kent et al. (2016), who discovered that asynchronous communications are essential in increasing reading outcomes. The finding on the effect of synchronous communications also reveals that increased synchronous communications increase the students’ reading scores. This finding supports Al-Jarf’s (2014) findings that students can improve their reading skills through synchronous communication. Overall, the findings are consistent with previous studies that support online collaborative communications as an effective tool for developing students’ reading comprehension, such as Hsieh and Ji (2013), Cummins (2008), and Lu and Chiou (2010); as students practice more in asynchronous and synchronous communication modes, their reading comprehension ability significantly improves. One possible explanation is that online communication requires students to share ideas with their peers, which helps them understand the course material. As a result, taking part in both online communication tasks may improve students’ reading comprehension.

To shed more light on the relationship between students’ perceptions and actual online communication conditions, the open-ended question results show that participants in the synchronous group have better perceptions of CMC than those in the asynchronous group regarding discussing with peers and feeling comfortable expressing ideas and asking questions. The synchronous communication platform offers a warm climate and greater ease, immediacy, convenience, and interaction (Al-Jarf, 2014). However, few students reported that late or unreturned messages from peers, as well as being unprepared for course materials, may have an impact on the effectiveness of the synchronous communication application. This finding is consistent with Ashley’s (2003) study, which found that while synchronous communication provides students with immediate feedback when needed, peer passive engagement may be a barrier when using an online communication platform.

Students in the asynchronous group recognize the online communication platform as most useful when they write personal comments and answers to increase self-paced learning. This finding is consistent with Skylar’s (2009) discovery that asynchronous learning provides ample time for responding and self-paced learning. However, the most common drawbacks mentioned for the Moodle application are the lack of notification when information is posted and the inconvenience of entering the username and password each time Moodle is accessed. This finding backs up Paulus’ (2007) finding.

Pedagogical Implications

Despite mixed feelings about the effectiveness of online communications, students’ responses to the open-ended question should be considered to maximize the benefits of the CMC task. To begin, instructors should work to resolve students’ login issues on Moodle and monitor WeChat’s chat box to make these two online tasks more effective and increase students’ active participation. Second, according to Reisetter and Boris (2004), students tend to self-select their preferred learning mode. To increase students’ motivation to engage in reading in online collaborative environments, reading instructors can consider balancing the two online communication modes based on individual learning preferences. Finally, as noted by Lang (2000), whether in synchronous or asynchronous communication mode, effective communication requires teachers to support students’ participation in a dialogical process that results in increasingly sound, well-founded, and valid understanding of a topic or issue. To improve students’ reading comprehension, instructors should take the time to prepare reading materials for communication topics or issues, with clear guidelines and feedback deadlines.

Limitations and Future Research

This study aims to compare the efficacy of asynchronous and synchronous communication applications on EFL reading outcomes. The study’s conclusion, however, is tempered by several limitations. The first limitation is that, as a rapidly emerging domain of technology applications, it is necessary to concentrate more on investigating the relatively new technological online tools. Although the WeChat communication platform is widely used in Taiwan, future research could incorporate more recent synchronous apps such as Teams or What’s App. The second limitation of this study is that it only counts the number of student messages. To get a clear picture of students’ responses and understanding of texts, future research should focus on the content of students’ questions and answers and the time it takes to complete each CMC task. Furthermore, while this study only compares EFL students’ reading comprehension performance, the other three language skills (listening, speaking, and writing) should be examined to comprehensively understand EFL students’ online platform usage. Finally, generalizing the findings is difficult due to time constraints and the small sample size. As a result, a large sample size by comparing the three groups: an asynchronous group, a synchronous group, and a control group, could present a generalizable conclusion.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology [MOST 107-2410-H-214-004].

References

Alfassi, M. (2004). Reading to learn: Effects of combined strategy instruction on high school students. Journal of Educational Research, 97(4), 171–184.

Al-Jabri, A. (2012). Saudi college students’ preferences for synchronous and asynchronous web-based courses: An exploratory study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Indiana State University.

Al-Jarf, R. (2005). Connecting students across universities in Saudi Arabia. Online Submission. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED497940.pdf

Al-Jarf, R. (2014). Integrating Elluminate in EFL reading instruction. Bucharest, 3, 19-26.

Ashley, J. (2003). Synchronous and asynchronous communication tools. Retrieved from http://www.asaecenter.org/PublicationsResources/articledetail.cfm?ItemNumber=13572

Carroll, N. (2011) Evaluating online asynchronous support in the institutes of technology Ireland. All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 3(2). Retrieved from https://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/50

Chau, V. B. (2017). Synchronous and asynchronous learning. Computer Science. Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Synchronous-and-Asynchronous-Learning-hauhan/48c279efde31e1b09dbc5368bddb7457fb9965e9

Chen, D., Klein, D., & Minor, L. (2008). Online professional development for early interventionists: Learning a systematic approach to promote caregiver interactions with infants who have multiple disabilities. Infants and Young Children, 21(2), 120-133.

Chen, H. (2013). The impact of the use of synchronous and asynchronous wiki technology on Chinese language reading and writing skills on high school students in south Texas. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University-Kingsville.

Chen, N. S., Teng, D. C. E., Lee, C. H., & Kinshuk. (2011). Augmenting paper-based reading activity with direct access to digital materials and scaffolded questioning. Computers & Education, 57, 1705-1715.

Cheng, C. K., Pare, D. E., Collimore, L. M., & Joordens, S. (2011). Assessing the effectiveness of a voluntary online discussion forum on improving students’ course performance. Computers & Education, 56(1), 253-261.

Cummins, J. (2008). Technology, literacy, and young second language learners. In L. L. Parker (Ed.), Technology-mediated learning environments for young English learners: Connections in and out of school (pp. 61-98). New York: Erlbaum.

Ding, H. (2019). Development of technical communication in China: Program building and field convergence. Technical Communication Quarterly, 28(3), 223-237.

Fitzgerald, J., & Graves, M. F. (2005). Reading supports for all. Educational Leadership, 62(4), 68-71.

Gikandi, J. W., & Morrow, D. (2016). Designing and implementing peer formative feedback within online learning environments. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 25(2), 153-170.

Goggins, S., & Xing, W. (2016). Building models explaining student participation behavior in asynchronous online discussion. Computers & Education, 94, 241-251.

Guo, M., & Wang, M. (2018). Integrating WeChat-based mobile-assisted language learning into college English teaching. EAI Endorsed Transactions on E-Learning, 5(17), 1-12.

Hewitt, J. (2005). Toward an understanding of how threads die in asynchronous computer conferences. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 14(4), 567-589.

Hirotani, M. (2006). The effects of synchronous and asynchronous computer-mediated communication (CMC) on the development of oral proficiency among novice learners of Japanese. Retrieved from http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/dissertations/AAI3185769/

Hsieh, P. C., & Ji, C. H. (2013). The effects of computer-mediated communication by a course management system (MOODLE) on English reading achievement and perceptions. International Conferences on Advanced Information and Communication Technology for Education, pp. 201-205.

Hu, G. (2005). Using peer review with Chinese ESL student writers. Language Teaching Research, 9(3), 321-342.

Jong, B. S., Lai, C. H., Hsia, Y. T., Lin, T. W., & Liao, Y. S. (2014). An exploration of the potential educational value of Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 32, 201-211.

Kent, C., Laslo, E., & Rafaeli, S. (2016). Interactivity in online discussions and learning outcomes. Computers & Education, 97, 116-128.

Koda, K., & Zehler, A. M. (2008). Introduction: Conceptualizing reading universals, cross- linguistic variations, and second language literacy development. In K. Koda, A. M. Zehler (Eds.), Learning to read to across languages: Cross-linguistics relationships in first and second language literacy development (pp. 1-9). New York, NY: Routledge.

Kosalka, M. (2011). Using synchronous tools to build community in the asynchronous online classroom. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/asynchronous-learning-and-trends/using-synchronous-tools-to-build-community-in-the-asynchronous-online-classroom/

Lage, T. M. (2008). An exploratory study of computer assisted language learning (CALL) glosses and traditional glosses on incidental vocabulary learning and Spanish literature reading comprehension. Unpublished master’s thesis, Iowa State University.

Lang, A. (2000). The limited capacity model of mediated message processing. Journal of Communication, 50(1), 46-70.

Langan, J. (2005). Ten steps to improving college reading skills. Bookman Books, Ltd.

Li, J., Tang, Y., Cao, M., & Hu, X. (2018). The moderating effects of discipline on the relationship between asynchronous discussion and satisfaction with MOOCs. Journal of Computers in Education, 5, 279-296.

Lin, Q., Qin, R., & Guo, J. (2016). An empirical study on northwest minority preppies’ self-efficacy in English learning on WeChat platform. Technology-assisted Foreign Language Education, pp. 171, 34–38.

Lu, H., & Chiou, M. (2010). The impact of individual differences on e-learning system satisfaction: A contingency approach. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(2), 307-323.

McBrien, J., Jones, P., & Cheng, R. (2009). Virtual spaces: Employing a synchronous online classroom to facilitate student engagement in online learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10(3). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/605/1264

Moodle. (2007). Retrieved from http://moodle.org

Ng, K. C. (2007). Replacing face-to-face tutorials by synchronous online technologies: Challenges and pedagogical implications.International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 8(1). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/View/335/764

O’Rourke, B., & Stickler, U. (2017). Synchronous communication technologies for language learning: Promise and challenges in research and pedagogy. Language Learning in Higher Education, 7(1), 1-20.

Palvia, S., & Palvia, P. (2007). The effectiveness of using computers for software training: An exploratory study. Journal of Information Systems Education, 18, 479-489.

Pan, C. Y. (2010, November). A survey on Tzu-Chi university freshmen’s application of English reading strategies. 2010 Conference on Teaching Excellence, Taiwan.

Paulus, T. (2007). CMC modes for learning tasks at a distance. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4). Retrieved from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol12/issue4/paulus.html

Reisetter, M., & Boris, G. (2004). What works: Student perceptions of effective elements in online learning. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 5(4), 277-291.

Rezaee, A. A., & Ahmadzadeh, S. (2012). Integrating computer mediated with face-to-face communication and EFL learners’ vocabulary improvement. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 3(3), 346-352.

Shadiev, R., Hwang, W. Y., & Huang, Y. M. (2015). A pilot study: Facilitating cross-cultural understanding with project-based collaborative learning in an online environment. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(2), 123-139.

Shadiev, R., Wu, T. T., Sun, A., & Huang, Y. M. (2018). Applications of speech-to-text recognition and computer-aided translation for enhancing cross-cultural learning: issues and their solutions. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(1), 191-214.

Sistelos, A. (2008). Human-computer interaction and cognition in e-learning environments: The effects of synchronous and asynchronous communication in knowledge development. Retrieved from Dissertations & Theses database.

Skylar, A. (2009). A comparison of asynchronous online text-based lectures and synchronous interactive web conferencing lectures. Issues in Teacher Education, 18(2), 69-84.

Stephens, K. K., & Mottet, T. P. (2008). Interactivity in a web conference training context: Effects on trainers and trainees. Communication Education, 57(1), 88-104.

Tsuei, M. (2011). Development of a peer-assisted learning strategy in computer-supported collaborative learning environments for elementary school students. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(2), 214-232.

Vonderwell, S., & Zachariah, S. (2005). Factors that influence participation in online learning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 38(2), 213-230.

Watson, K., McIntyre, S., & McArthur, I. (2010). Trust and relationship building: Critical skills for the future of design education in online contexts. Iridescent, 1(1), 22-29.

Wilson Van Voorhis, C. R., & Morgan, B. (2007). Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 3(2), 43-50.

Yuan, J., & Kim, C. (2018). The effects of autonomy support on student engagement in peer assessment. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(1), 25-52.

Zapata, G., & Sagarra, N. (2007). CALL on hold: The delayed benefits of an online workbook on L2 vocabulary learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 20(2), 153-171.

Zhang, J., Anderson, R. C., & Nguyen-Jahiel, K. (2013). Language-rich discussions for English language learners. International Journal of Educational Research, 58, 44-60.

Zhang, J., Niu, C., Munawar, S., & Anderson, R. C. (2016). Research in the Teaching of English, 51(2), 183-208.

Zhang, W., & Zhu, C. (2017). Review on blended learning: Identifying the key themes and categories. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 7(9), 673-678.

Hui-Fang Shang, ED.D. was born in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. In 1996, she earned her doctorate in Educational Leadership at University of Southern California in USA. Currently she is a Full Professor of Department of Applied English at I-Shou University, Taiwan. She has been the Chair of Department of Applied English, Director of Center for Teaching and Learning Development, and Dean of College of Language Arts at I-Shou University. Hui-Fang Shang has published 49 journal papers (including 13 SSCI and 8 CIJE papers), 63 conference papers, and conducted 42 research projects. She has also been the SSCI journal reviewers for Computer Assisted Language Learning, British Journal of Educational Technology, Educational Studies, and Educational Researcher. Her expertise and research interests include TEFL, CALL, and curriculum design and assessment. You can reach Dr. Hui-Fang Shang at hshang@isu.edu.tw.