doi.org/10.55177/tc862277

By Scott A. Mogull

ABSTRACT

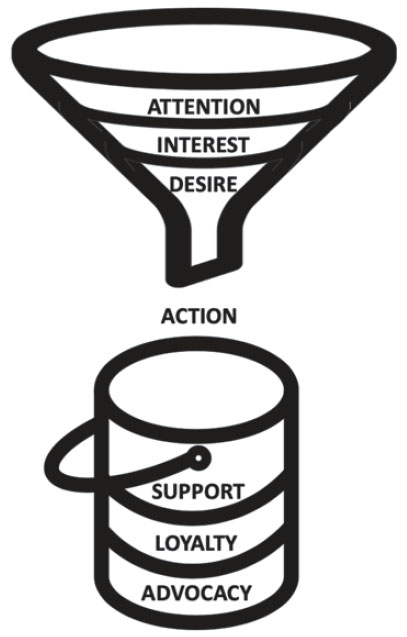

Purpose: In this article, the content strategy for technical content marketing (TCM) is examined for a start-up tech company, Terra Solar, commercializing a “do-it-yourself” (DIY) home solar power kit that makes clean energy more affordable and accessible to a wider range of consumers. Notably, this article illustrates the role of technical communication in technical content marketing using the funnel-bucket model, a framework for implementing content strategy for new products, to inform the communication goals of an entrepreneurial technology company and provides a framework for implementing content marketing publication strategy for new technical products.

Method: This case study integrates theory, research, and industry practices of content strategy, technical content marketing, advertising, digital marketing, and technical communication.

Results: This article situates strategic marketing plans with the theory of content strategy and includes a review of the latest research in content marketing to provide readers with a research-based guide for planning the commercialization strategy for technology products.

Conclusion: This case study describes the use of the funnel-bucket model as a framework for planning TCM genres to provide a coordinated set of informative and persuasive product-related information through multiple media platforms to reach target technical buyers.

Keywords: Content Strategy, Technical Content Marketing, Funnel-Bucket Model

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Shows the use of the funnel-bucket model for technical content marketing to model the content strategy of a technology company.

- Provides a framework for planning and publishing content marketing for new technical products

This case study examines the content strategy of marketing communications (marcom) for a start-up tech company developing a “do-it-yourself” (DIY) home solar power assembly kit that is more affordable and accessible to a wider range of consumers. Balancing informative and promotional objectives, technical content marketing (TCM) genres are planned and published strategically to provide potential customers—and intentionally repeat customers—with relevant and useful information about a technical product or service as these individual audience members progress through their personal customer journey that includes collecting information about a technology category and a specific product, selecting and purchasing of one product from a competitive market, and ultimate progression to a brand-loyal evangelical for a specific product and tech company (Geier, 2015; Mogull, 2021; Pulizzi, 2014).

The content strategy of TCM is based on the classical AIDA (Attention, Interest, Desire, and Action) model for marketing communications, which has been updated after the point of purchase to include communications that promote technical consumer loyalty (Geier, 2015; Strong, 1925). With this framework, TCM requires continuous, multiphase evolution of messaging and media to reach different target audiences as technology evolves the innovation life cycle (Mogull, 2021). Notably, effective TCM is more than the aggregate of marketing genres with similar messaging communicated through various media. Rather, a successful content strategy for tech companies is to become, in essence, a “multimedia publisher” that coordinates useful information, genres, and media channels to target awareness and education to specific buyer personas and thus create a genre-constructed demand for a company’s products or services (Pulizzi, 2014; Revella, 2015).

In this case study, the content strategy is examined for a start-up tech company, Terra Solar, in the year leading up to the product launch as the marketing plan for TCM is developed for the company’s first product—the Solar Canopy. Based in the Texas State University Science, Technology, and Advanced Research (STAR) Park, Terra Solar implemented the latest research-informed marcom strategy to develop its marketing plan. In this case study of the marketing plan for the Solar Canopy, the following two research questions were explored:

- What genres and media are used to communicate a new technical product to potential buyers (innovators and early adopters) at the time of initial product launch?

- What is the content (or message) of each communication and how does that message contribute to the larger network, or communication strategy, about the product?

This article provides a model-based marketing plan for tech companies to use as a TCM publication calendar in the selection of genres, media, and messages—which establishes the groundwork for a marketing publications department.

Technical Content Marketing Theory

Technical content marketing (TCM) is the collection of all communications about a technical product (or service) with the goal to provide relevant, useful, coordinated, and consistent information to target buyers through various media and interpersonal sources (Ames, 2017; Mogull, 2021; Pulizzi, 2014). Content marketing is a network of interconnected genres with various messaging that discourages a “hard sell” overtly promoting a product, but rather attracts an audience for each genre based on the merit of the information relevance or entertainment value of each communication (Pulizzi, 2014; Wall & Spinuzzi, 2018). In a content marketing publications ecosystem, audiences are provided an array of informative and reliable content about a technology category so that the company, the brand, creates a reputation for being a reliable source of information within a technology market space. In theory, this brand credibility transfers ethos to the product itself so that TCM audiences eventually become product consumers (Pulizzi, 2014).

Content Strategy

Content strategy is the unified planning and distribution of all communications that supports the organization’s business plan (Clark, 2016; Getto et al., 2019a; 2019b; Harner & Zimmerman, 2002; Redish, 2012; Rockley & Cooper, 2012). Notably, content strategy connects communications among departments in a siloed organization to communicate a consistent message and voice from the organization (Getto et al., 2019b). In practice, the content strategy of organizations includes the planning, writing, and publishing of all external communications through various multimedia channels to provide relevant and consistent messaging to a variety of audiences to sustain the organization (Flanagan & Getto, 2017). For example, nonprofit organizations require a robust multimedia presence that delivers various genres to serve relevant and distinct audiences (such as volunteers, donors, and clients) to enable the organization’s overall objectives (Flanagan & Getto, 2017; Getto et al., 2019b). More specifically, commercial organizations typically develop a written content strategy, or marcom plan, that includes all decisions of communications (Pulizzi, 2014). The elements of content strategy include (Batova & Andersen, 2016):

- Substance: Message, genre, and media,

- Structure: Format and metadata,

- Workflow: Tools and practices to create, maintain, and retire content, and

- Governance: Evaluation that content meets the strategic intention of the business plan.

- Collectively, these elements dictate the UX of all communications to rhetorically motivate target audiences towards specific outcomes that achieve the organization’s objective (Andersen, 2014; Dolezal, 2019; Getto, 2019; Hovde, 2019; McDaniel, 2008). Subsequently, content strategy provides direction to the seemingly copious number of communications created and published by organizations.

Content Strategy of Technical Content Marketing

TCM encompasses all forms of brand communication and rhetorical strategy by organizations. Marketing strategy is organized into the 4Ps (Keller, 2003), which include:

- Product: the appearance of the product, features of technology, and user experience (UX),

- Promotion: advertising and marketing genres for the product, which includes the overall content strategy,

- Price: the value of the technology to the target consumer, and

- Place: channel of distribution or marketplace.

Collectively, the 4Ps contribute to the rhetorical construction of a brand image in the mind of consumers. This image, the “brand,” is the singular message that an organization, technical product, or service represents and connotatively influences the audiences’ judgments and feelings to construct personal resonance and promote engagement, attachment, loyalty, and community among consumers or other groups associated with the brand (Keller, 2003).

Strategically, brands are developed by organizations. All factors and combinations of factors including product design, technology UX, TCM or promotion, and interactions with other individuals reference the brand to create the brand image and differentiate it along some dimension (for example, quality, value, or social impact) from the competition (Keller, 2003). Brand image and value are established rhetorically through logos, pathos, ethos, or some combination of these classical Aristotelian modes of persuasion (Hardesty, 2009; Mogull, 2018a). For ethical promotion or content strategy of TCM, this means delivering reliable, clear, and accessible information through a variety of media that serve multiple audiences’ needs for information along each stage of their journey through the awareness, information gathering, alternative selection, and support phases (Mogull, 2022). Often for technology, the credibility of a brand is based on the quality of the argument, with logos as the pinnacle, followed by pathos, and least from ethos (Mogull, 2018a). Furthermore, ethical TCM of product claims for a typical user and undistorted information about the technology are essential (Mogull, 2022; Mogull, 2018b). TCM is a category of technical communication that is designed to strategically develop and shape a product market by converting audiences to technology users. Particularly in the case of complex, expensive, or unfamiliar technology, the strategy is the promotion of the general technology platform to solve a consumer need, such as the benefits of home solar power, with limited product-specific marketing genres such as the Solar Canopy webpage. However, the content or focus of TCM is selected to reflect the specific benefits or applications of a particular product for which the company has a customer niche or user advantage to rhetorically develop the conversation about certain needs or wants over others. This reverse selling strategy—to promote the product category before the product itself—is seen in the construction and communication through technology and media channels that enable readers to navigate freely and, more specifically, consume, leave, and then return to various genres within the company-constructed information ecosystem (Wall & Spinuzzi, 2018). Holistically, the delivery of useful technical information constructs the brand’s ethos by satisfying the audience’s need for information as well as their user expectations for on-demand, customized, portable content for information access anytime and anywhere (Anderson, 2014). In essence, purposeful and reliable content delivery of TCM is the first step in establishing consumer knowledge and brand trust for future purchases of an innovative technical product or service.

The marketing and sales funnel-bucket model provides a framework for planning the content strategy of a tech company and, more specifically, publishing different technical content marketing genres at various stages of the technology customer decision journey (Ames, 2017; Batra & Keller, 2016; Dolezal, 2019; Geier, 2015). Historically, the marketing and sales funnel, or AIDA (Attention-Interest-Desire-Action) model, was originally developed for advertising to consumers who progress from lack of awareness about product availability to eventual purchase—as long as the messaging and product fit are appropriate for the target audience (Strong, 1925). In the marketing and sales funnel (Figure 1), consumers progress through the following stages, which are useful for constructing the messages of various genres:

- Attention: Gain initial awareness of a new product,

- Interest: Develop interest and increase knowledge about a product,

- Desire: Create a feeling of want to own or use a product, and

- Action: Supplement the actions necessary to purchase a product.

As represented by a funnel, each stage narrows the size of the audience that will ultimately progress to the “action” stage of product purchase. Thus, TCM content strategy requires reaching a target audience through media channels with appropriate messaging of technology or product benefits that engages the audience and encourages them to follow a somewhat anticipated path to the next stage of the customer decision journey in which the TCM provide additional informative and persuasive content leading to the next stage (Ames, 2017; Batra & Keller, 2016; Dolezal, 2019; Geier, 2015).

In terms of TCM, these stages are rarely accomplished through a single interaction with only one genre. Rather, a coordinated ecosystem of TCM genres including websites, social media, press releases, and consumer feedback, help construct audience perception and ultimate purchase of a product or service (Batra & Keller, 2016; Dolezal, 2019; Geier, 2015; Wall & Spinuzzi, 2018). Furthermore, comprehensive content strategy of tech companies develops lifelong consumer relationships that continue after product purchase at the action stage. In addition to customer support materials (instructions and FAQs), companies also pursue a positive long-term relationship with customers that are developed through TCM strategies to generate company or product loyalty and, ideally, advocacy of a brand (Dolezal, 2019; Geier, 2015). These post-sales genres of TCM, which are part of a content strategy, are represented as a bucket beneath the funnel (Figure 1) to reflect the importance accumulating customers and nurturing these relationships so they become engaged, loyal users of a technology and, ideally, brand evangelists who promote the technology through product use and “word-of-mouth” online customer reviews (such as blog and social media posts) that amplify product awareness and information. Thus, both acquisition of new customers and retention of existing customers, particularly in markets with multiple product options, are the primary goals of TCM genres throughout the marketing and sales funnel-bucket model (Gordon, McKeage, & Fox, 1998; You & Joshi, 2020).

Content Strategy of the Funnel-Bucket Model in a Startup Tech Company

In the following examination of the start-up tech company Terra Solar, content strategy provides product awareness and delivering technical information through typified genres and media (Mogull, 2019; Mogull, 2021). In this analysis of Terra Solar, the implementation and analysis of a content strategy for the content marketing of entrepreneurial technology is traced as the start-up tech company transitions from the funding and prototype stage to the commercialization stage for the Solar Canopy, a “do-it-yourself” (DIY) assembly kit for affordable and accessible consumer solar power. More specifically, when communicating a new technology to a potential consumer market, the content strategy of the start-up tech company transitioned from seeking investors in the technology and company to marketing the Solar Canopy to potential consumers. The content strategy for commercialization of technology, the TCM content strategy, becomes an online network of coordinated marketing communications about the Solar Canopy and consumer solar energy for target audiences. For this strategy, technical content marketing genres were designed to provide educational, informative, and persuasive content at various stages along a multi-step process of developing product awareness, communicating technical information, selecting the company’s product from similar technologies, and ultimately purchase of the technology (Geier, 2015; Pulizzi, 2014; Wall & Spinuzzi, 2018).

Batra & Keller’s (2016) Communications Optimization Model (7Cs) was used to develop the TCM content strategy of Terra Solar’s Solar Canopy to maximize audience reach and contribution of the typified message of each genre, while accounting for cost (or limited expense), for a start-up tech company with a limited marketing budget. According to Pullizzi (2011), the objectives of a content marketing strategy include:

- Brand awareness or reinforcement,

- Lead conversion and nurturing,

- Customer conversion,

- Customer service,

- Customer upsell, and

- Passionate subscribers.

As part of the TCM content strategy, the conformability, or the unique information journey of individuals through a genre network, was designed to place product-centric genres at the center of a broader genre ecosystem promoting the market for a scalable, DIY-assembly kit for consumer solar power by providing content to reach target technical buyers. Within Terra Solar, the marketing department becomes a publications department (Pulizzi, 2014; Samson, 1988). The genre categories for Terra Solar’s TCM content strategy are as follows (Batra & Keller, 2016; Dolezal, 2019; Geier, 2015):

- TCM communications hub (website),

- Company-owned TCM publishing media (company-written TCM blog & direct mail/email),

- Paid media for internal website traffic (online search/display ads), and

- Earned media for internal website traffic and an external online network (company-owned social media microblogs, external social media microblogs, external blogs, press coverage, and organizational partnerships).

In the following section, each genre category and strategic outcome are discussed in greater detail.

TCM Communications Hub

Fundamentally, Terra Solar developed an online presence for the company through a company website with the goal of persuading potential technology customers to purchase the Solar Canopy through detailed information. Approximately one month prior to the product launch, Terra Solar launched a preliminary Web presence of TCM. The primary communication outcomes of a TCM website are to convey detailed information promoting the technical product and to connect potential buyers with the company staff and other brand enthusiasts such as earned-media outlets (journal and organization news releases and outside bloggers reporting on the technology or market) or satisfied customers (consumer social media accounts) to leverage interpersonal sources and social forms of TCM (Bass, 1969; Batra & Keller, 2016; Geier, 2015; Mahajan et al., 1990; Mogull, 2018a; Mogull 2021; Mohr et al., 2010).

The technology brand website served as the hub of the technical content marketing ecosystem about the consumer-solar panel/off-grid ecosystem by funneling visitors (or potential customers) from online advertising, direct mail/email, and social media blogs (Geier, 2015). Specifically, the website becomes a valuable information resource with embedded search-engine optimization (SEO) strategies to attract targeted visitors, provides detailed technical product information about the Solar Canopy that supports the product positioning statement, and is organized with the supporting benefits and features (Hardesty, 2009; Harner & Zimmerman, 2002; Mogull, 2018; Teague, 1995). As stated by Batra and Keller (2016), conveying detailed information focuses on “persuading consumers about brand performance [and] requires that they appreciate the benefits of the products or services and understand why the brand can better deliver those benefits in terms of supporting product attributes, features, or characteristics” (p. 131). The pre-launch website also allows visitors to take immediate action by providing (1) company contact information for immediate support from sales associates to begin exploring product solutions to a potential customer’s personal needs and (2) an email address for future direct emails about the product. The post-launch website will be expanded to provide catalog and purchasing information/options, customer/technical support contact information, and product documentation as support forms of TCM (Wirtz-Brückner & Jakobs, 2018; Mogull, 2019).

The website also serves to expand awareness, create salience about the Solar Canopy, and elicit visitor emotion through persuasive and informative content (Geier, 2015; Batra & Keller, 2016). Holistically, the website develops and promotes a brand image through the quality and integrity of the communication (visual/verbal messages, media selections, and hyperlinking to news articles, press releases, and partnerships that notably include the Department of Energy American-Made Solar Prize, Texas State Ventures, EPIcenter Energy Incubator & Accelerator, and Tech Commercialization Center at the University of Texas at San Antonio SBDC) (Batra & Keller, 2016; Dolezal, 2019; Geier, 2015; Mogull, 2018a). Through the co-constructed knowledge and positive, credible external endorsements, Terra Solar seeds the foundations for technology brand ethos and loyalty by managing all points of online communication and promoting social/earned media connections (Geier, 2015; Batra & Keller, 2016). In the marketing and sales funnel-bucket model, Terra Solar’s Solar Canopy website functions as the TCM communication hub, and integrates all stages of the ideal technical buyer journey with the brand (Dolezal, 2019).

Company-Owned TCM Publishing Media

A content marketing program prioritizes publishing engaging and useful content that meets the informational needs of its target customers rather than focusing simply on the product itself (Pulizzi, 2014). For the start-up technology company Terra Solar, the TCM publishing platforms included a company-written blog and direct mail (specifically email). Through company owned TCM publishing media, construction of the Terra Solar brand ethos and expanded awareness by public sharing of content is enhanced by publishing information that appeals to the following positive emotions (organized from highest to lowest effect): (1) practical value, (2) awe, (3) interest, or (4) surprise (Berger & Milkman, 2012). Notably, external audiences frequently share this online content for altruistic reasons (e.g., to help others) or for self-promotion (e.g., to appear as an informed, knowledgeable source) (Berger & Milkman, 2012).

Blog posts published on a website and then shared on social media is the most common form of content marketing and should be published on a regular basis in order to attract new and recurring website visitors with the goal of providing valuable content for the targeted audience. This will likely make readers more inclined to forward and share them on social platforms, as well as other online sites (Vinerean, 2017). Visual blog posts, or technical infographics, are also used to communicate statistics, facts, or data visually. Thus, they provide a more compelling and engaging format that can summarize and convey large sets of information (or data) in a clear and easy to interpret light (Vinerean, 2017). Initially, the TCM blog posts and technical infographics planned by Terra Solar were to promote the market of scalable DIY, off-grid consumer solar power, and government incentives for investing in consumer solar power. Downstream following market launch, the TCM blog posts would be expanded to include customer case studies to share customer success stories that explain how the Solar Canopy helped a customer who represents a particular technical buyer persona (Vinerean, 2017). Company-written blog posts promote generic category demand for consumer solar power needs covered by Terra Solar and, as a credible source of information about the technical field, develop brand preference for Terra Solar (Batra & Keller, 2016). Blogs and other forms of social media create awareness and salience for a product or brand, convey brand imagery and personality, elicit emotions, and connect people to the brand (Batra & Keller, 2016). Specifically, social media as a category of interpersonal and social TCM influences the liking, loyalty, engagement, and advocacy of a technology and confers greater influence on brand selection than product-centric TCM (Batra & Keller, 2016; Mahajan et al., 1990).

Direct email (as a form of direct mail) functions to communicate directly to a list of previously collected addresses from prior website visitors and interpersonal connections to company representatives to convince them to take an action (Cheung, 2011; Hardesty, 2009). Many technical companies also purchase outside address lists from related organizations, although this strategy requires a large marketing budget so external email lists were not initially included in the TCM strategy. Initially, the first direct email was planned to announce the product launch, with subsequent and somewhat infrequent emails being used to announce new product availability. Specifically, the direct emails were an opportunity to reengage individuals who had former contact with the brand and would be potential consumers for purchasing the Solar Canopy when the product is launched. Notably, direct mail/email has the greatest impact on inspiring action and conveying detailed, benefit-focused information about a product or service (Batra & Keller, 2016). Direct mail/email also has a moderate influence on creating brand awareness and salience as well as instilling brand loyalty (Batra & Keller, 2016).

Paid Media for Internal Website Traffic

The “top of funnel” (Figure 1) goals awareness, interest, and desire have genres for online “findability” of websites and content marketing, which are planned to attract information-seeking online visitors through specific and targeted keyword advertising in online search engines and possibly expanding to online display ads on other websites (Batra & Keller, 2016; Dolezal, 2019; Geier, 2015; Morville, 2005). In general, prominent placement in online search engines through native search of keywords is unrealistic for the majority of companies, particularly start-up tech companies, and thus the majority of content providers rely on online advertising in search engines, social media platforms, and display ads to attract online visitors (Batra & Keller, 2016; Dolezal, 2019; Pan et al. 2007). Batra and Keller (2016) describe the objectives of these forms of media advertising as “messages that remind or trigger action [to visit a website offering a particular solution] rather than for messages that aim to persuade through detailed information” (p. 131). Thus, some investment into online advertisements is necessary to attract targeted online visitors to consume TCM. Search ads and display ads have the greatest influence on creating brand awareness and salience as well as medium to strong influence on inspiring action (Batra & Keller, 2016). Specifically, search ads and display ads funnel potential consumers through the stages of need recognition, awareness, examination of technical solutions, and learning about a product or service (Batra & Keller, 2016).

Earned Media for Internal Website Traffic and an External Online Network

Social media platforms for microblogging (external and company-owned), external social media microblogs and blogs (mentions, shares, reposts, and reviews), press coverage, and organizational partnerships create an external online network (or ecosystem) of partnering brands, functioning at both the top-of-funnel (awareness or “findability,” interest, and desire) and bottom-of-bucket (loyalty and advocacy) stages in the marketing and sales funnel-bucket model. Similar to paid media, these genres attract targeted, online visitors. However, unlike paid advertisements, earned media functions by providing positive interpersonal and social (word-of-mouth) endorsements (Batra & Keller, 2016; Mahajan et al., 1990). Both social media (company owned and external) and public-relations strategies are the strongest TCM strategies for constructing brand trust and eliciting emotions (Batra & Keller, 2016; Wood 2014). These communication networks that connect users, partners, advocates, and news media function to engage individuals with a brand beyond a company’s ecosystem and function to create brand awareness and salience as well as further developing a brand image (Batra & Keller, 2016; Lofstrom, 2010).

Marketing Communications Plan for the Solar Canopy

While Terra Solar’s overall goal is the sale of the Solar Canopy, the goal of publishing TCM is more than to announce or directly promote the product, but also to establish itself as the knowledgeable and trusted brand in the field of consumer solar power (Pulizzi, 2014; Wall & Spinuzzi, 2018). Metaphorically, content marketing publishing, as stated by Pulizzi (2014), is “like the job of museum curator…to unearth the best content on the planet in your niche so that your museum doesn’t close for lack of attendance” (p. 80). In the case of San Antonio, Texas-based Terra Solar, the “museum” audience consists of consumers of content related to consumer solar power—particularly for the regional Texas and US-based markets being the initial geographical regions, with particular focus on audiences potentially interested in small to scalable, DIY solar power assembly kits for either stand-alone or rooftop mount. Notably, though many large technical companies have global markets, and this is often the goal of start-up tech companies, consumer tech products are typically launched in one region at a time with specific configurations and regulations (such as electric compatibility with US-based systems). Furthermore, the value and benefits of the technology are locally constructed (Cruz-Cardenas et al., 2019; Sun, 2012, 2013) so the marketing communications plan provides a localized Texas and US-centric content strategy for the initial product launch of the Solar Canopy.

A successful TCM content strategy, or marketing communications plan, is to publish specific genres through different media platforms with predominantly informational content that is needed or wanted by target audiences in a technical market. For Terra Solar, the goal of the TCM content strategy is to direct relevant and useful information to niche markets (e.g., solar power for scalable/entry-level homeowners, tiny homes, camping, or gardens). Each target audience represents part of the bowling alley strategy of Terra Solar to focus on the solar power product needs of a niche market and then promote solar power use within the market (Mogull, 2021). Similar to the strategy initially used by LinkedIn, this approach by Terra Solar focuses on serving the needs of a small, relatively similar technical audience that have been previously unaddressed by other companies. As a product and service, TCM with a content strategy designed to reach these target technical audiences serves as the first example of the quality and accessibility of product and service from the company. Notably, delivering content to target technical audiences that is more accessible and better tailored to the specific audience’s desire and need for information significantly contributes to the construction of the ethos of Terra Solar (Smart et al., 1996).

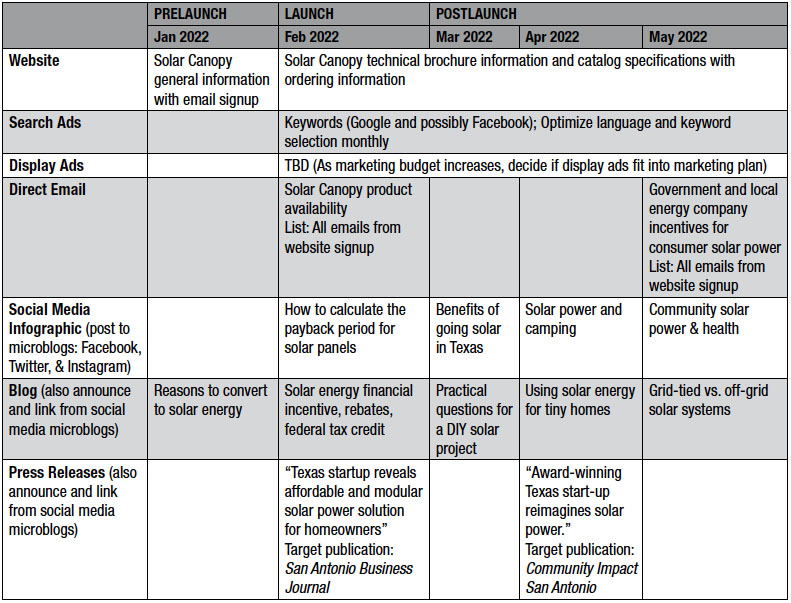

The marketing communications plan for the Solar Canopy from one month prior to product launch through the first four months of product availability is provided in Table 1. In this pre- to post-launch marketing communications plan, relatively consistent post-launch product information is provided on the company website. However, the content strategy is to provide consistent publishing of relevant information through monthly blog posts (announced on social media microblogs), monthly infographics posted to social media microblogs, bimonthly coverage in the news media through targeted press releases, and occasional direct emails to reengage potential website visitors. Additionally, the content strategy includes monthly review of search ad effectiveness (and optimization), with the opportunity to incorporate display ads in the future as the marketing budget increases. As each specific target audience, or niche “bowling pen” customer segment (e.g., small/DIY off-grid solar power market) has their information needs met through TCM, Terra Solar shifted to focusing content for a different niche market. Overall, the strategy of addressing customer segment markets was to design TCM from the largest to smallest market opportunity (considering the company’s position within the marketplace and geographical region). Ultimately, the TCM content strategy for these online genres leverages operational efficiency through information reuse, accessibility, navigation/interaction, immediacy, and marginal marketing cost (Koiso-Kanttila, 2004; Rowley, 2008). These foundational online content strategy outcomes should be later developed further to promote personalization, interactivity, and user agency (Valos et al., 2010).

The content strategy for the marketing communications plan is designed to attract regular visitors to the company website. This goal is achieved by regularly publishing new content that is informative and useful to niche technical audiences through informative blog posts, social media microblog announcements and infographics, and press releases. In this marketing communications plan following product launch (in February 2022), the following three months are focused on reaching under-served, niche solar power consumers in tiny homes, camping, and small off-grid systems (including community projects). Furthermore, future blog posts and press coverage following these first three months would not only address other niche consumer audiences but reengage these prior audiences by incorporating customer case studies and community partnerships—both showing successful and interesting implementations of the Solar Canopy, which are then also announced through social media.

Conclusion

This article examined the content strategy framework for technical content marketing (TCM) genres and media platforms of Terra Solar throughout the customer decision journey for the Solar Canopy. Using the marketing and sales funnel-bucket model as a guide for planning the genres and media platforms to inform and persuade potential customers, the marketing communications plan listed monthly tactics (or activities), which provides the publication timeline for TCM. Planning, writing, and delivering technical content marketing holistically based on a content strategy (rather than as individual, isolated genres) helps construct a coordinated technical buyer journey through the marketing and sales funnel-bucket model by:

- Establishing a clear and consistent perception of a product,

- Maximizing resources through effective content management that reuses core information and delivers target, niche audience-specific content through different media sources,

- Building a brand ethos and image that resonates with consumers, and

- Continually testing, optimizing, and publishing TCM as a “museum” of information on the market and product or technology.

As Baehr (2013) stated, “Effective content strategy is iterative and evolving; over time it is sustainable and closely linked to standards and practices that govern a body of knowledge” (p. 305).

References

Ames, A. L. (2017). Content marketing: The straightest line between content and customer. Intercom, 64(8), 12-13.

Andersen, R. (2014). Rhetorical work in the age of content management: Implications for the field of technical communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 28(2), 115-157. https://doi. org/10.1177/1050651913513904

Baehr, C. (2013). Developing a sustainable content strategy for a technical communication body of knowledge. Technical Communication, 60(4), 393-306.

Bass, F.M. (1969) A New Product Growth Model for Consumer Durables. Management Science, 15, 215-227. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.15.5.215

Batra, R., & Keller, K. L. (2016). Integrating marketing communications: New findings, new lessons, and new ideas. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 122-145.

Batova, T. & Andersen, R. (2016). Introduction to the special issue: Content strategy—a unifying vision. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59(1), 2-6. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2016.2540727

Berger, J., & Milkman, K. L. (2012). What makes online content viral? Journal of Marketing Research, 49(2), 192-205. https://doi. org/10.1509/jmr.10.0353

Cheung, M. (2011). Factors affecting the design of electronic direct mail messages: Implications for professional communicators. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 54(3), 279-298. https://doi. org/10.1109/TPC.2011.2161800

Clark, D. (2016). Content strategy: An integrative literature review. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59(1), 7-23. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2016.2537080

Cruz-Cardenas, J., Zabelina, E., Deyneka, O., Guadalupe- Lanas, J., & Velin-Farez, M. (2019). Role of demographic factors, attitudes toward technology, and cultural values in the prediction of technology-based consumer behaviors: A study in developing and emerging countries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 149, 119768. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119768

Dolezal, J. (2019). A flight to quality? Why content marketing strategy must evolve. Journal of Brand Strategy, 7(3), 343-354.

Flanagan, S., & Getto, G. (2017). Helping content: A three-part approach to content strategy with nonprofits. Communication Design Quarterly, 5(1), 57-70. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119768

Geier, R. (2015). Smart marketing for engineers: An inbound guide to reaching technical audiences. Rockbench.

Getto, G. (2019). What constitutes a best practice in content strategy? In G. Getto, J. Labriola, & S. Ruszkiewicz (Eds.), Content strategy in technical communication (pp. 19-30). Routledge.

Getto, G., Labriola, J., & Ruszkiewicz, S. (2019a). An introduction to content strategy: Best practices, pedagogies, and what the future holds. In G. Getto, J. Labriola, & S. Ruszkiewicz (Eds.), Content strategy in technical communication (pp. 1-16). Routledge.

Getto, G., Labriola, J., & Ruszkiewicz, S. (2019b). A practitioner view of content strategy best practices in technical communication: A meta-analysis of the literature. In Proceedings of the 37th ACM International Conference on the Design of Communication (pp. 1-16). https://doi. org/10.1145/3328020.3353943

Gordon, M. E., McKeage, K., & Fox, M. A. (1998). Relationship marketing effectiveness: The role of involvement. Psychology & Marketing, 15(5), 443-459.

Hardesty, B. (2009). Writing to persuade: Why technical communicators can move into marketing writing. Intercom, 56(8), 14-17.

Harner, S. W., & Zimmerman, T. G. (2002). Technical marketing communication. Pearson.

Hovde, M. R. (2019). Effects of content management and organizational context on technical communication’s usability. In G. Getto, J. Labriola, & S. Ruszkiewicz (Eds.), Content strategy in technical communication (pp. 69-88). Routledge.

Keller, K. L. (2003). Strategic brand management: Building, measuring, and managing brand equity (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall.

Koiso-Kanttila, N. (2004). Digital content marketing: A literature synthesis. Journal of Marketing Management, 20(1-2), 45-65. https://doi. org/10.1362/026725704773041122

Lofstrom, J. (2010). A collaborative approach for media training between technical communication and public relations. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 53(2), 164-173. https://doi.org/ 10.1109/TPC.2010.2046091

Lucas, K., Kerrick, S. A., Haugen, J., & Crider, C. J. (2016). Communicating entrepreneurial passion: Personal passion vs. perceived passion in venture pitches. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59(4), 363-378. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2016.2607818

Mahajan, V., Muller, E., & Srivastava, R. K. (1990). Determination of adopter categories by using innovation diffusion models. Journal of Marketing Research, 27(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3172549

McDaniel, R. (2008). Experiences with building a narrative web content management system: Best practices for developing specialized content management systems (and lessons learned for the classroom). In G. Pullman & G. Baotung (Eds.), Content management: Bridging the gap between theory and practice (pp. 15-42). Routledge.

Mogull, S. A. (2018a). Primary messages of DTC advertising during the product life cycle: A case study. In 2018 IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (ProComm) (pp. 150-158). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ProComm.2018.00039

Mogull, S. A. (2018b). Science vs. science commercialization in neoliberalism (extreme capitalism): Examining the conflicts and ethics of information sharing in opposing social systems. In H. Yu & K. M. Northcut, Scientific communication: Practices, theories, and pedagogies (pp. 64-81). Routledge.

Mogull, S. A. (2019). Genres as silos for technical communication: Considerations for spanning boundaries in academia and industry. In P. Minacori (Ed.), Technical communication: Beyond silos (pp. 65-86). Hermann.

Mogull, S. A. (2021). Technical content marketing along the technology adoption lifecycle. Communication Design Quarterly, 9(2), 27-35. https://doi.org/10.1145/3453460.3453463

Mogull, S. A. (2022). Legal and ethical issues in technical content marketing. AMWA Journal, 37(1).

Morville, P. (2005). Experience design unplugged. ACM SIGGRAPH 2005 Web Program on – SIGGRAPH ‘05. https://doi.org/10.1145/1187335.1187347 Pulizzi, J. (2011). Inbound marketing isn’t enough. Content Marketing Institute. https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/2011/11/content-marketing-inbound-marketing

Pan, B., Hembrooke, H., Joachims, T., Lorigo, L., Gay, G., & Granka, L. (2007). In google we trust: Users’ decisions on rank, position, and relevance. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(3), 801–823. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00351.x Pulizzi, J. (2014). Epic content marketing. McGraw-Hill.

Redish, J. (2012). Letting go of the words: Writing Web content that works (2nd ed.). Morgan Kaufmann.

Revella, A. (2015). Buyer personas: How to gain insight into your customer’s expectations, align your marketing strategies, and win more business. Wiley.

Rockley, A., & Cooper, C. (2012). Managing enterprise content: A unified content strategy (2nd ed.). New Riders.

Rowley, J. (2008). Understanding digital content marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 24(5-6), 517-540. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725708X325977

Samson, D. (1988). A publications department’s role in marketing. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 31(2), 88-92. https://doi.org/10.1109/47.6930

Smart, K. L., Madrigal, J. L., & Seawright, K. K. (1996). The effect of documentation on customer perception of product quality. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 39(3), 157-162. https://doi.org/10.1109/47.536264

Strong, E. K. (1925). The psychology of selling and advertising. McGraw-Hill.

Sun, H. (2012). Cross-cultural technology design: Creating culture-sensitive technology for local users. Oxford University Press.

Sun, H. (2013). Sina Weibo of China: From a copycat to a local uptake of a global technology assemblage. International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development, 5(4), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijskd.2013100103

Teague, J. H. (1995). Marketing on the World Wide Web. Technical Communication, 42(2), 236-242.

Valos, M. J., Ewing, M. T., & Powell, I. H. (2010). Practitioner prognostications on the future of online marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(3-4), 361-376. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/02672571003594762

Vinerean, S. (2017). Content marketing strategy. Definition, objectives and tactics. Expert Journal of Marketing, 5(2), 92-98.

Wall, A., & Spinuzzi, C. (2018). The art of selling-without-selling: Understanding the genre ecologies of content marketing. Technical Communication Quarterly, 27(2), 137–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2018.1425483

Wirtz-Brückner, S., & Jakobs, E-M. (2018). Product catalogs in the face of digitalization. In 2018 IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (ProComm) (pp. 98-106). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ProComm.2018.00030

Wood, M. B. (2014). The marketing plan handbook (5th ed.). Pearson.

You, Y., & Joshi, A. M. (2020). The impact of user-generated content and traditional media on customer acquisition and retention. Journal of Advertising, 49(3), 213-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2020.1740631

Scott A. Mogull, Ph.D. is a professor in the Technical Communication Program at Texas State University. He held multiple editorial roles for Technical Communication Quarterly for over 10 years. His research focuses on the commercialization of technology. Prior to entering academia, he spent 8 years in the biotechnology and biodefense industries, where he wrote and oversaw the production of technical videos while in the marketing department. He may be reached by email at mogull@txstate.edu.