doi.org/10.55177/tc749689

By Michael J. Madson

ABSTRACT

Purpose:Few studies in our field have investigated corporate communications at the origins of the United States opioid crisis, which arguably began around the mid-1990s. Such analyses can illuminate executives and managers’ collective thinking at the time (that is, “communal rationality”), nuance our public narratives, and recommend ways that technical communicators can engage further with this public health tragedy. Thus, this article surfaces the communal rationality expressed in the launch plan for OxyContin, which I obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request. This is perhaps the first close reading of a pharmaceutical launch plan in our scholarly literature.

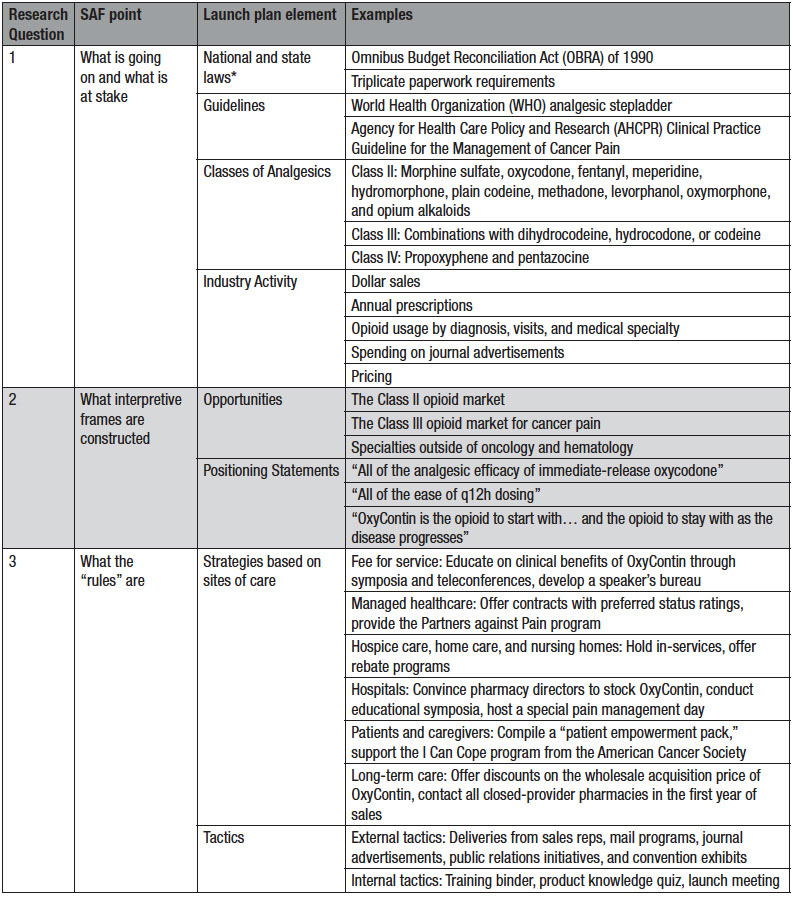

Method:Following precedent in other research, I applied a three-point heuristic based on the concept of strategic action fields: what is going on and what is at stake, what interpretive frames are constructed, and what the rules of the game are.

Results:The communal rationality expressed in the launch plan involves a complex tangle of cultural knowledge, including state and national laws, guidelines, classes of analgesics, and industry practices. The writers effectively translate this knowledge into opportunities, positioning statements, strategies, and tactics.

Conclusion:In some ways, the launch plan is an exemplary piece of technical and professional communication, but its treatment of ethics and risk is highly problematic—arguably making it an example of communication failure as well. Future research should delve deeper into the opioid crisis, exploring additional promotions, genres, drugs, and methodologies.

Keywords:Opioid Crisis, OxyContin, Communal Rationality, Strategic Action Field, Launch Plan

Practitioner’s Takeaways:

- In launch plans for drugs, especially controlled drugs, technical communicators must carefully weigh how they represent the market, develop product profiles, and target potential buyers.

- Marketing should not be disguised, and where needed, technical communicators should seek professional development in health literacy, bioethics, and marketing ethics.

- Technical communicators must elevate their professional ethics above the “concepts, values, traditions, and style” of the biomedical discourses that they produce.

- Beyond that, we must work to reimagine the boundaries of these discourses and advocate for more culturally responsive, inclusive approaches to communication—pre-launch, peri-launch, and post-launch.

It was a mild autumn day in Norwalk, Connecticut, when a project manager named Michael submitted a lengthy document to his colleagues. The document, timestamped with the year 1995, was in some respects unremarkable. Like others of its genre, it contained a hierarchical organization of text, passive voice, careful hedging, a few typos in subject/verb agreement, and tables of numerical data. The writers had, at one point, mistaken a 4 for a 9 in a column labeled “annual dollar sales,” but they had still correctly calculated the rate of growth. In other respects, the document was electric, a source of heightened power and risk. Michael’s team did not realize it then, but the document would contribute to windfall profits, tighter regulation of the industry, litigation against company executives, and a staggering degree of human misery.

This was the launch plan for OxyContin, a long-acting tablet containing oxycodone (a Class II opioid). Manufactured by Purdue Pharma, OxyContin would soon become one the most notorious painkillers implicated in the United States opioid crisis.

The opioid crisis has been called “one of the largest and most complex public health tragedies that [the United States] has ever faced” (Gottlieb, 2019), and it has attracted wide coverage in journalism and scholarship. In the field of technical and professional communication (TPC), scholars have focused on community outreach efforts (Batova, 2019; Bivens, 2018; Dreher, 2018), data visualization and racial disparities (Welhausen, 2022, 2023), and multiple ontologies embodied by those suffering from chronic pain (Graham & Herndl, 2013; Graham, 2015), among other topics. This work has been valuable. To date, however, few TPC studies have examined corporate communications at the origins of the crisis, including the launch plan for OxyContin. The launch plan is of particular importance because it depicts how executives and managers collectively perceived market conditions in the United States at the time. In addition, the launch plan is a persuasive document, issuing recommendations that would shape later decisions by the company. Thus, the launch plan is a prime example of kairotic communication, and it suggests that the development and promotion of OxyContin was motivated by more than runaway greed. It was also a matter of “communal rationality,” the seemingly “contextless logic” that undergirds biomedical discourses (Miller, 1979, p. 617; DeTora, 2021, p. 222).

This article analyzes the communal rationality expressed in the launch plan for OxyContin, taking the concept of “strategic action field” (SAF) as a heuristic. First, I locate the analysis in relevant literature on drugs, product launches, and communal rationality, highlighting research gaps. Second, I describe the concept of SAF, relying on the influential work of sociologists Neil Fligstein and Doug McAdam (2011, 2012). Third, I lay out the research questions and apply the heuristic, which has three points: what is going on in the SAF and what is at stake, what interpretive frames are constructed, and what the rules of the game are, especially in terms of strategies and tactics. Fourth and finally, I discuss the findings, drawing implications for TPC professionals, both practitioners and scholars.

Drugs, Product Launches, and Communal Rationality

TPC scholarship has long engaged with the social complexities surrounding drugs, with early studies in our journals dating to the 1970s (Aziz, 1974; Montague, 1971). Since then, much scholarship in this area has analyzed genre, focusing on clinical investigator brochures (Pakes, 1993), drug information leaflets (Maat & Klaasen, 1994; Maat & Lentz, 2011), clinical trial protocols (Bell et al., 2000), clinical study reports (Cuppan & Bernhardt, 2012; DeTora, 2017), patient safety narratives (DeTora & Klein, 2020), presentations at federal committee meetings (Graham et al., 2015; Teston et al., 2014), and product labels (Agboka, 2014, 2021; Ding, 2004; Kessler & Graham, 2018). Some TPC scholarship has focused on drug advertising (Davis, 1999) and product launches in other industries (Boyd et al., 1997; Spinuzzi, 2010). Few if any TPC studies have investigated the launch plans for new drugs.

When accessible, launch plans are significant documents to study because of their industry uses and historical value. In short, launch plans position new drugs on the market: they pinpoint ways that the drugs can stand out from competitors, identify target audiences, and propose future actions. As a result, launch plans, if effective, can enable pharmaceutical companies to recoup the money spent on research and development, which, across the industry, totaled $83 billion in 2019 (Congressional Budget Office, 2021). Since most new drugs do not pass clinical trials, pharmaceutical companies will expend considerable resources, coordinated through launch plans, to ensure that drugs approved by federal agencies are a financial success (Natanek et al., 2017). Relatedly, launch plans are historical documents, providing a cross-section of market conditions and executive thinking at a particular time. Because they contain confidential information, launch plans are not usually released to the public in the absence of a judicial order. That has been the case with Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin. But now that the launch plan for OxyContin is publicly accessible, allowing for deeper investigations into the origins of the United States opioid crisis and its enduring impacts (see Alpert et al., 2021), questions arise over how to proceed.

Helpfully, TPC scholarship on drugs has resurfaced the notion of communal rationality, which can provide a path forward. The term in TPC can be traced to 1979, when Carolyn Miller advocated for a “flagrantly rhetorical approach” to the teaching of TPC. Under such an approach, instructors acknowledge that the act of writing involves participation in a community, including “concepts, values, traditions, and style which permit identification with that community and determine the success or failure of communication” (Miller, 1979, p. 617). It follows that instructors should teach “a broader understanding of why and how to adjust or violate the rules, of the social implications of the roles a writer casts for himself or herself and for the reader, and of the ethical repercussions of one’s words” (Miller, 1979, p. 617). We can thereby “ground our teaching and our discipline in a communal rationality rather than in contextless logic” (Miller, 1979, p. 617).

The term was recently picked up by Lisa DeTora (2021) in a book chapter on biomedical discourses and regulatory documentation. DeTora (2021) argued that we should understand biomedical discourses, with their positivistic overtones, as a “series of different intellectual cultures, each of which constitutes itself rationally, as described in its accepted guidelines” (p. 222). To outsiders, biomedical discourses may indeed seem like contextless logic and, consequently, pose challenges for reading. These challenges range from structured formats (e.g., IMRaD) that leave readers to piece together the overall meaning for themselves, to semantic slippage: that is, the same term can mean different things, even within the same sentence. The communal rationality of biomedical discourses, DeTora (2021) added, can be illuminated through studies of regulatory documents, such as statements from the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, ethical codes, regulations, and requirements from professional societies. These studies can concretize the “concepts, values, traditions, and style” that the various stakeholders expect (see Miller, 1979, p. 617).

DeTora (2021) makes cogent arguments, reflecting her firsthand experience in, and insightful scholarship on, the pharmaceutical industry. Yet, her book chapter is general in focus, and regulatory documents alone will only partly illuminate the communal rationality operating in certain biomedical genres, such as launch plans. Launch plans are produced for company insiders and are not subject to the same regulatory requirements as, say, clinical trial reports, product labels, or even advertisements. Moreover, companies will generally keep their internal guidelines for the “concepts, values, traditions, and style” (Miller, 1979, p. 617) expected in launch plans confidential. Thus, to advance studies of communal rationality, we will need to find additional heuristics. In this article, I consider communal rationality in terms of SAF, which already has precedent in analyses of biomedical discourses. For example, SAF has guided studies of biotechnology in Australia (Gilding & Pickering, 2011), homecare nursing in Norway (Melby et al., 2018), medical communications in Japan (Schrimpf, 2018), psychotropic drugs in Brazil (Sato, 2018), and state responses to the opioid crisis (Smith et al., 2021). Because it is new to TPC scholarship, SAF merits some explanation here.

Strategic Action Fields

SAF has roots in the groundbreaking work of Pierre Bourdieu, who theorized “fields”: socially structured spaces where actors produce, circulate, and contest forms of capital, including goods, services, information, and status (Bourdieu, 1977; Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992). SAF also has roots in Anthony Giddens’ (1979, 1984) structuration theory, institutional theory in political science and sociology, and social movement theory. Acknowledging these influences, Fligstein and McAdam (2012) define SAFs as a meso-level social order, the basic building blocks of collective action (pp. 3, 9-10). Similar concepts in sociological research include sectors, games, networks, policy domains, and markets. Like these concepts, SAFs are embedded and scalable, and Fligstein and McAdam (2012) suggest a large, corporate office as an illustration. The office may belong to a larger division within the firm, and the firm may compete with other companies that participate in an international division of labor—all of which can be understood as SAFs, creating systems of proximate and distal fields (pp. 9, 18-19).

What distinguishes an SAF, then? According to Fligstein and McAdam (2012), SAFs rest on several underlying understandings that go beyond the logics of similar concepts: Actors will share a general understanding of what is going on in the SAF and what is at stake, construct and apply interpretive frames to understand each other’s actions, and agree on the rules of the game.

What Is Going On And What Is At Stake

The boundaries of an SAF are never static or stable, and low-level competition is the norm. Yet, when an SAF is settled (rather than in upheaval), the actors will eventually agree on what is happening in the SAF and what is at stake. Actors may not agree that the current conditions in the SAF are legitimate, “only that the overall account of the terrain of the field is shared by most actors” (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, pp. 11, 88, 170). Since membership in an SAF is subjective, actors can be understood as “those groups who routinely take each other into account in their actions,” qualitatively or quantitatively (pp. 167-168).

Interpretive Frames

Interpretive frames are “hypotheses about the sorts of events that may be encountered in a given scenario,” such as expectations, projections, or models for a course of action (Cornelissen & Werner, 2014, p. 188; cf. Lakoff, 2014). In harmony with Bourdieu (1977), interpretive frames may vary with the actors’ positions and power within an SAF. Those in power, or incumbents, will usually seek to normalize and maintain the status quo whereas challengers will tend to adopt oppositional perspectives. In either case, skilled actors can apply their interpretive frames in ways that appeal to existing identities and interests, eliciting cooperation from allies and casting enemies in a negative light (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, p. 11). Practically, interpretive frames often manifest as opportunities and threats that the actors construct (Fligstein & McAdam, 2011).

Interpretive frames can be affected by governance units, which oversee compliance and facilitate smooth operations. Governance units are not “neutral arbiters” when conflict arises, contrary to the rhetorics that may justify their actions (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, pp. 14, 78). Rather, governance units tend to reinforce dominant perspectives and protect the interests of incumbents. Some governance units are internal to an SAF while others, such as state agencies, are external.

What The “Rules” Are

No matter their position in an SAF, skilled actors know strategies and tactics that are “possible, legitimate, and interpretable” at a given time and in a given role (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, pp. 11, 88, 170). Fligstein and McAdam (2012) call this cultural knowledge “social skill.” That is, “the ability to empathetically understand situations and what others need and want and to figure out how to use this information to get what you want” (p. 178). Amid contention, skilled actors not only construct opportunities and threats. They also engage in organizational appropriation, linking threats and opportunities to resources, such as communications, trainings, and funding (Fligstein & McAdam, 2011, p. 9). Actors may subsequently take up innovative action, violating SAF rules in support, or in defense of, their identities and interests (Fligstein & McAdam, 2011).

Like interpretive frames, some social skill varies with actors’ positions and power in the SAF. To defend the status quo, incumbents may employ cooptation, merger, and imitation. Challengers may find niches where an incumbent will not go and wait for a crisis when they can take advantage. They may even attempt to institute a new configuration of power, such as by establishing new rules, forming a political coalition, or advancing “a new set of cultural understandings that reorganizes [actors’] interests and identities” (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, p. 189). In product launches, actors may deploy targeting strategies (who to sell to?), timing strategies (when to act?), and strategies to communicate the product’s innovativeness (what is different or new?) (Guiltinan, 1999, p. 516).

The concept of SAF thus seems well suited for an analysis of the communal rationality expressed in the OxyContin launch plan. The pharmaceutical industry, in the mid-1990s and now, is riven with competition. As companies continually work to out-maneuver each other, they occupy a variety of positions, and they are mediated by governance units, such as the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Indeed, the concept of SAF assumes that “people are always acting strategically” (Fligstein & McAdam, 2011, p. 7), a useful stance for analysis. Moreover, some writers have argued that Purdue Pharma succeeded in selling not just opioid pills, but the very idea of opioids (see, e.g., Meier, 2018, p. 39), making the company’s interpretive frames, along with strategies and tactics, particularly salient.

In this article, I subsequently adopted terminology, relationships, and focal points baked into the concept of SAF, which I took as a three-point heuristic: what is going on in the SAF and what is at stake, what interpretive frames are constructed, and what the rules of the game are, especially in terms of strategies and tactics. Certainly, this is not the only way of parsing the communal rationality in the launch plan, I received unredacted through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the Florida Attorney General. But SAF may provide valuable insights.

Research Questions

Corresponding to the three-point heuristic, this article centers on three research questions.

R1: How does the launch plan describe what is going on and what is at stake in the SAF? Or in other words, how does the launch plan describe the market conditions for OxyContin?

R2: What interpretive frames does the launch plan construct?

R3: Subsequently, what strategies and tactics does the launch plan propose?

The following sections show how I applied the heuristic, analyzing the communal rationality expressed in the OxyContin launch plan (refer to Table 1 for a summary). Unless otherwise indicated, the parenthetical citations indicate where in the launch plan the information appears.

R1: How Does the Launch Plan Describe What Is Going on and what Is at Stake in the SAF?

The launch plan for OxyContin does not lay out a specific purpose statement. It contains little in the way of an or conclusion to bookend the various sections, which focus on market data and assumptions, the new product profile for OxyContin, and a communication plan. Rather, Michael’s team of writers builds their arguments from numerous forms of cultural knowledge that include national and state laws, guidelines, classes of analgesics (painkillers), and industry activity displayed on 18 tables in the appendices.

National And State Laws

The writers mention national and state laws throughout the launch plan. One national law is the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA), which mandated standards for patient counseling. Under the act, a pharmacist would offer counseling to Medicaid recipients when they filled a prescription (p. 25). Other national laws pertain to specific classes of opioids, which for clarity, I discuss in the next subsection.

The state laws mentioned in the launch plan govern triplicate paperwork requirements (pp. 4, 6, 27, 49). To prescribe opioids, a physician would need to make three copies of the paperwork: the physician would keep one themselves. The pharmacist would keep another copy after filling the prescription, and then send a third copy to a government health agency. The agency would monitor prescription patterns and, as needed, investigate irregularities. In the 1960s, California became the first state to adopt triplicate paperwork requirements, followed by Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, New York, and Texas (see Alpert et al., 2022).

Guidelines

The writers cite two sets of guidelines: the analgesic stepladder proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) (Ventafridda et al., 1985) and, to a lesser extent, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Cancer Pain (Jacox et al., 1994).

The analgesic stepladder, which the writers reference more than 20 times, was originally developed to guide the treatment of cancer patients. It consists of three steps that account for the severity of pain and the recommended medication.

Step 1, mild pain. Patients should receive medications other than opioids, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen, with or without adjuvants. An adjuvant is a substance added to a drug that increases its strength or efficacy.

Step 2, moderate pain. Patients should receive “weak” opioids such as codeine, hydrocodone, or tramadol, without or without adjuvants, and without or without additional non-opioid painkillers. (Many analgesics contain a combination of opioids and non-opioids, which potentially alleviate a patient’s pain through multiple neural pathways.)

Step 3, persistent and severe pain. Patients should receive “strong” opioids such as buprenorphine, fentanyl, methadone, morphine, or oxycodone, with or without adjuvants, and with or without non-opioid painkillers (see also Anekar & Cascella, 2021).

The writers also cite the AHCPR Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Cancer Pain (pp. 21, 22, 24). The guideline was developed by a multi-disciplinary panel of clinicians, who conducted extensive reviews of the scientific literature and identified, according to their professional judgment, areas where the literature was inconsistent or incomplete (Jacox et al., 1994). As a result, the guideline reflected the then-current state of knowledge of cancer pain management. Among other things, the guideline emphasized that the undertreatment of cancer pain was widespread, even though effective management was possible in most patients, up to 90% of them. Although it endorsed multimodality—a blend of drug and non-drug approaches to pain management—the guideline expressed generally positive views on opioids (Jacox et al., 1994, chapter 3).

Classes Of Analgesics

The writers refer repeatedly to Class II, Class III, and Class IV analgesics. The class depended largely on the active ingredients, or “chemical types.”

Nine chemical types were part of Class II analgesics: morphine sulfate (e.g., MS Contin), oxycodone (e.g., Percocet), fentanyl (e.g., Duragesic), meperidine, hydromorphone, plain codeine, methadone, levorphanol, oxymorphone, and opium alkaloids. These chemical types underwent further categorization when they were combined with a non-opioid painkiller, such as “APAP” (acetaminophen) or “ASA” (acetylsalicylic acid, often branded as Aspirin).

Other combinations fell into Class III and IV. Class III analgesics included combinations with dihydrocodeine, hydrocodone, or codeine. Class IV analgesics contained propoxyphene or pentazocine.

The class divisions were not only a matter of chemistry. There could also be regulatory differences between classes, as the writers explain. Class II analgesics fell under the strictest regulations for marketed drugs. For example, Class II opioids could not be “phoned in to the pharmacy,” and in some states, had triplicate paperwork requirements. In contrast, Class III and IV opioids required some recordkeeping, but they could be phoned in (pp. 4, 6).

At points, the writers refer to opioid classes as “categories” or “markets.”

Industry Activity

Industry activity, quantified in the appendices, include dollar sales, annual prescriptions, usage by diagnosis or visits, spending on journal advertisements, and pricing. The writers made their calculations based on other pharmaceutical companies that share membership in the SAF, including Forest, Geneva, Janssen, Knoll, Lilly, McNeil, Monarch, Roche, Roxane, Ruby, Sandoz, Sanofi, Upsher-Smith, Whitby, and Wyeth.

Dollar sales

The writers display dollar sales for leading Class II analgesics from the prior five years (1990 to 1994) along with growth rates (Table 1). They do the same for the oxycodone market (Table 2). For Class III and IV analgesics sold in retail drugstores, the writers consider only the prior two years (1993 to 1994), calculating the percent of change and overall market shares for each drug (Table 3).

Annual prescriptions

The writers display, similar to dollar sales, the annual prescriptions for leading Class II analgesics from the prior five years along with growth rates (Table 4). They do the same for the oxycodone market (Table 5). For Class III and IV analgesics, they consider only the prior two years, calculating the percent of change and overall market shares for each drug (Table 6).

Opioid usage by diagnosis/visits

These data came from the National Disease and Therapeutic Index or NDTI. From these data, which are limited to the prior year (January to December 1994), the writers detail several categories of diagnoses for which physicians could prescribe opioids. The categories include postoperative pain, neoplasms (cancer pain), musculoskeletal pain, arthritis, injury and trauma pain, central nervous system pain, as well as gastrointestinal and urinary disorders. They also include “ill defined” conditions, sickle cell anemia pain, HIV/AIDS pain, and “all other diagnosed conditions.” Based on the raw numbers of visits, the writers calculated the percent of visits by diagnosis for Class II opioids altogether (7A, 7B), MS Contin and Duragesic (7C), oxycodone brands (8A, 8B). They ran the same numbers for Class III opioids altogether (9A, 9B).

Opioid usage by medical specialty

The writers also display, for the prior year, prescriptions by medical specialty. Tables 10A and 10B focus on oxycodone prescriptions. At the top of the tables are primary care (including family practice, general practice, osteopathic medicine, and immunology) and surgery (including orthopedic, general, and “all other surgeons). In the middle and bottom of the tables are 16 additional specialties, ranging from dentistry and OB/GYN to pediatrics, physical medicine, and “all other M.D.’s.” The table cells show the number of total prescriptions in unrounded numbers (Table 10A) and the percent of prescriptions by product (Table 10B).

Table 11 focuses on “selected leading strong opioid analgesics” for the prior year. This table has two main sections, the first of which shows data on five medical specialties: oncology/hematology, internal medicine, primary care (defined as family practice, general practice, osteopathic medicine), anesthesiology, and surgery (general, orthopedic, neurological, and “other”). The second section shows data on 13 additional specialties, ranging from pulmonary care and neurology to physician medicine, dentistry, pediatrics, and “all others.” As in Tables 10A and 10B, the row labels in Table 11 generally correspond to the highest prescribing specialties to the lowest, and for each, the writers calculated both total prescriptions and share of prescriptions.

Spending on journal advertisements

The writers display the money spent on journal advertisements for the oral pain market, which is comprised of Lorcet, Vicodin, Oramorph, Duragesic, Dilaudid, Ultram, Roxicodone, and Percocet. The table is limited to the years 1993, 1994, and 1995, which appear as columns. Because Michael would submit the launch plan in September 1995, the writers divided that year into two columns: 1995 “year-to-date” (current as of May) and 1995 “projected.”

Pricing

Table 13 features “the prices for major Class II and III brand and generic products considered to be direct competition for OxyContin.” There are four columns: The first is “product,” and it shows various opioids on the market, including the product name, the manufacturer, the dosage, and the form (e.g., whether the medication is a tablet or solution). The second shows ex-factory pricing, referring to the cost of purchasing the drug directly from the manufacturer. The third shows the average wholesale prices, and the fourth is “percent spread,” which indicates the difference between ex-factory and average wholesale prices.

In their analysis, the writers do not elaborate on this table, but they do show approved pricing for OxyContin at 10, 20, and 40 milligrams, as well as much stronger dosages (80 and 160 mg) that Purdue Pharma was planning. They add, “A thorough and comprehensive price sensitivity study will be conducted to ascertain the optimal price for OxyContin” in various markets (p. 53). Altogether, these forms of cultural knowledge suggest what is going on and what is at stake in the SAF, providing a foundation for the communal rationality behind the launch.

R2: What Interpretive Frames Does the Launch Plan Construct?

The 18 tables in the launch plan appendices show that Purdue Pharma held multiple positions within the SAF. For morphine sulfate products, the company was an incumbent: from 1993 to 1994, sales for MS Contin grew by nearly $20 million, a growth rate of 26.5%. This growth “came in the face of stiff competition” from two challengers: Duragesic and Oramorph SR (p. 1). Citing Purdue’s own market research, the writers report that “MS Contin has become the gold standard for treating moderately severe to severe cancer pain (W.H.O. Step 3)” (p. 12).

For other products, Purdue Pharma was a challenger. Aside from MS Contin, the writers mention only three other Purdue products in the launch plan: DHC Plus, a dihydrocodeine combination product that came to market in April 1993; “MSIR,” which may stand for “morphine sulfate immediate release”; and “MSIR concentrate.” All three medications, along with their pricing, appear in Table 13. Based on the company’s positions as both incumbent and challenger, the writers construct several opportunities in the SAF.

Opportunities

The first opportunity in the SAF: The Class II opioid market

To make this claim, the writers need to downplay the “relatively flat” sales of oxycodone products since 1994 (p. 3). They explain that the sales numbers resulted from the growing availability of generics on the market, but notwithstanding that competition, success is still possible. The leading oxycodone product, Percocet, had reached a sales volume of $44.1 million. Another oxycodone product, Roxicet, had reached a modest $18.6 million but had a remarkable growth rate of 59.8% in the prior year. Strategically, the writers mention that the leading oxycodone products–Percocet, Tylox, and Percodan–are combination drugs, meaning that they contain more than oxycodone alone. They also contain acetaminophen or aspirin. These additional painkillers stimulate an additional neural pathway to relieve pain, but they run the risk of damaging the liver or kidneys.

Relatedly, the writers need to explain away the “relatively flat” growth for oxycodone prescriptions, which, the year prior, had grown only 1.0%, to $11.2 million (p. 5). It could be reasonably inferred from these data that physicians had some hesitance in prescribing oxycodone. Or perhaps there was inadequate market demand generally. Speculating, the writers attribute the lack of growth to the introduction of opioids that are long-acting, a key feature of OxyContin.

OxyContin is a single-entity oxycodone product, so the writers also note the anemic sales for single-entity oxycodone products, which captured only $2 million in sales – less than 2% of the total market. To reassure readers that OxyContin is still viable, they make connections to MS Contin. As mentioned above, MS Contin had become the “gold standard” for cancer pain, with a sales volume of $88 million, a growth rate of $26.4% (p. 12). This growth had come impressively in the face of “stiff competition” from other branded drugs, like Duragesic (a fentanyl patch) and Oramorph SR (a morphine sulfate drug that cost less than MS Contin) (p. 1). The numbers were equally impressive for prescriptions: MS Contin remained strong in that area, accounting for nearly two-thirds of all prescriptions.

However, the patent for MS Contin would soon expire, enabling generic copycats to enter the market by 1997, so the writers emphasize how generics had undermined the sales of other drugs. Generics had already undermined the sales of oxycodone products like Percocet. In addition, they stress that generics were the “dominant-growing force” in hydrocodone combinations, and that generic combination opioids would continue growing overall (p. 6).

Another threat, albeit a minor one, would come from branded drugs, notably Kadian. Kadian is a morphine sulfate drug that, like MS Contin, delivers the active ingredient over much of the day. But unlike MS Contin, Kadian had the potential to secure a “q24h” dosing indication, meaning that patients would only need to take a single pill per day–that is, every 24 hours. The drug had already come to market in Australia, where sales reps had argued that Kadian provided “flatter plasma concentrations” than MS Contin (p. 13). In theory, flatter plasma concentrations signaled greater efficacy. The writers anticipated that Kadian would siphon prescriptions away from MS Contin. Thus, they argue that “one of the major strategies in launching OxyContin will be to replace all prescriptions for MS CONTIN” (p. 3). MS Contin was becoming a liability, and OxyContin could fill that gap and more.

The writers make connections to drugs that already competed with MS Contin in the United States. Duragesic had been selling well since its launch in 1992. However, its growth had slowed “due to problems with its delivery system” (p. 5). Duragesic had also experienced problems with the FDA (pp. 2, 13), creating an opening to capture prescriptions from that patient demographic. Because Duragesic and MS Contin were the only long-acting Class II opioids on the market, they “should be the major competitors” for OxyContin (p. 3).

Another competitor was hydromorphone, which was prescribed largely for cancer pain. Hydromorphone products had grown a modest 6.9% in the previous year, the slowest growth rate of any leading Class II analgesic, to $23.6 million. The writers note that much of that sales volume came from the Dilaudid product line, though generics had reached $4.3 million (p. 2).

The second opportunity in the SAF: The Class III opioid market for cancer pain

Again, connections to MS Contin serve a persuasive purpose. According to the writers, company market research had indicated that “most physicians and nurses” recommended morphine products, like MS Contin, after combination opioids were no longer effective for patients (p. 4). However, these physicians and nurses had shown interest in prescribing OxyContin “in place of the shorter-acting combination opioids, earlier in the treatment cycle than MS Contin or Duragesic for cancer pain” (p. 4).

This market potential for a Class III opioid was significant, and the writers do not minimize the regulatory barriers. Single-entity oxycodone was a Class II opioid, which could not be phoned into a pharmacy. Moreover, some states required triplicate paperwork, and Purdue would subsequently work to reform these regulations.

The third opportunity in the SAF: Specialties outside of oncology and hematology

The writers do not recommend abandonment of the cancer pain market, of course. OxyContin would, in theory, eventually replace all prescriptions for MS Contin, and oncologists represented more than a third of all prescriptions for that drug in a given year. Another third came from primary care physicians. The writers consequently decide that “Overall, oncology/hematology represents the primary target for promoting OxyContin” (p. 11).

Limiting OxyContin to the cancer pain alone would be a significant opportunity cost, given the data on which physicians prescribed oxycodone products. Of all prescriptions for these products, primary care physicians accounted for 28%, and surgeons (especially orthopedic and general surgeons) for 24%. The remainder came from a variety of specialties, but of note, dentists accounted for 15%, and obstetricians and gynecologists for 7.2%.

Purdue would not be the first company to promote opioids to other specialties. The writers state that Janssen Pharmaceuticals, the maker of Duragesic, targeted not only oncologists, but internists and other primary care physicians. Indeed, primary care physicians were increasingly prescribing Duragesic, a sign that the marketing was working. It would be reasonable, then, to follow suit. The writers recommend that “The primary care physicians… must also be considered a primary target, and physician-prescribing information by decile must be used to target the highest potential physicians” (p. 11).

The writers take a step further. Going beyond their data, they emphasize the influence that oncology nurses have on prescriptions decisions, even though nurses may lack prescribing privileges themselves. Similarly, the writers note that, in hospice and home health care settings, it is typically nurses who see patients the most, rate patients’ pain, and recommend the type and dosage of opioid needed for pain control. In short, OxyContin could be marketed beyond cancer care and physicians alone. Earlier in the launch plan, the writers state that Oramorph SR, a competitor to MS Contin that sold at a cheaper price, had benefited from “an aggressive marketing campaign” (p. 1).

Positioning Statements

To take advantage of these opportunities and encourage organizational appropriation (see Fligstein & McAdam, 2011), the writers recommend several positioning statements for OxyContin. The positioning statements, which suggest language for later advertisements, emphasize the cultural values of efficacy and ease.

“All of the analgesic efficacy of immediate-release oxycodone”

This positioning statement appeals to physicians’ familiarity with oxycodone, the importance of which “cannot be overstated” (p. 14). The writers translate this statement into several overlapping selling points, such as “Pain relief begins promptly, within one hour,” “Rapid onset of action,” and “Rapidly effective–upon initiation, most patients can expect relief within one hour” (p. 15).

“All of the ease of q12h dosing”

This statement draws on seven market research studies involving 626 healthcare professionals. The studies had all concluded that q12h dosing– meaning that the drug would slowly release its active ingredient into a patient’s bloodstream over 12 hours–was “the most compelling reason to prescribe OxyContin” (p. 14). With q12h dosing, patients would presumably need to take fewer doses during the day and, as a result, experience more consistent pain relief.

“OxyContin is the opioid to start with… and the opioid to stay with as the disease progresses”

This statement alludes to the WHO analgesic stepladder. The writers claim that there was “No ‘ceiling’ to analgesic efficacy.” Thus, OxyContin could be titrated as far upward as necessary, or in other words, patients could take stronger and stronger doses without losing pain relief (p. 16). Patients could start OxyContin for moderate pain, and continue to take it if the pain intensity increased to severe levels.

These positioning statements could distinguish OxyContin from its competitors, which could change over time. The FDA, a key governance unit in the SAF, was set to approve the drug initially for cancer pain. But after the company had enough clinical trial data to support broader promotions, sales reps could expand the drug into other pain markets. In the meantime, the company should avoid pigeon-holing the drug in the cancer pain market alone. They would need to develop specific strategies and tactics that SAF actors would perceive as “possible, legitimate, and interpretable” (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, pp. 11, 88, 170).

R3: What Strategies and Tactics Does the Launch Plan Propose for Purdue Pharma?

To leverage the positioning statements and selling points, and to further encourage organizational appropriation, the writers differentiate strategies from tactics. Strategies focus on sites of care, namely fee for service; managed healthcare; hospice care, home care, and nursing homes; hospitals; patients and caregivers; and long-term care.

Strategies

The first site of care is fee for service, where the key audiences are the top physicians (across specialties) who prescribe opioids, as well as oncology nurses. The strategies include the following actions, which blended drug promotion with medical education—potentially a form of innovative action.

- Educate the key audiences on the clinical benefits over other Step 2 opioids, as well as over Step 3 opioids. The writers remind readers that “OxyContin should be positioned as the opioid to start with in Step 2 of the W.H.O. stepladder and the opioid to stay with as the disease progresses through Step 3” (p. 21).

- Use symposia, teleconferences, and other medical education formats to spread word about the clinical benefits of OxyContin. A speaker’s bureau for OxyContin was in the works, and once the participating physicians had received their training, the sales force could utilize them.

- Using the AHCPR Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Cancer Pain, educate the key audiences on “appropriate” techniques for managing patients’ pain. In particular, sales reps should emphasize that “opioids are the cornerstone of pain management,” and that the oral route was preferred (p. 21). This was a way of arguing for not only OxyContin in general, but OxyContin over Duragesic (a fentanyl patch) in particular.

- Educate patients and caregivers about cancer pain management, expanding the company’s Partners Against Pain Program. Specifically, patients and caregivers should communicate pain and seek help in controlling it.

The second site of care is managed healthcare, where the key audiences are the contract negotiation teams, pharmacy benefit managers, pharmacists, oncologists, oncology nurses, and primary care physicians who prescribed the most opioids. The strategies include:

- Offer contracts with preferred status ratings.

- Develop multi-centered trials to show that OxyContin offers better quality of life and cost savings compared to its competitors.

- Provide continuing education programs to physicians, nurses, and pharmacists on pain management principles. These programs would emphasize OxyContin as the preferred Step 2 opioid.

- Provide the Partners Against Pain program as a value-added service, along with other organization-specific programs to educate health care professionals on pain management.

The third site is hospice care, home care, and nursing homes, where the key audiences are medical directors, consultant pharmacists, nurses, patient care coordinators, and continuing education coordinators. The strategies include:

- Give in-services at organizations serving patients with cancer pain. As at other sites of care, sales reps would emphasize the benefits of OxyContin as a Step 2 opioid. In addition, they would emphasize the ease and frequency of OxyContin dosing (which provides “around the clock pain relief that allows patients to sleep through the night and plan out their days”), its cost effectiveness, and its short administration time compared to shorter-acting opioids, like Percocet (p. 23).

- Offer the Partners Against Pain Program “to assist in empowering the patient” (p. 23).

- Offer a hospice rebate program modeled after the one for MS Contin, which would take a percentage off the ex-factory price for all patients at the facility.

The fourth site is hospitals, where the key audiences are all cancer centers in the United States (n ≈ 1,200), all major teaching institutions (n ≈ 1,200), and all community hospitals with more than 100 beds (n ≈ 2,500). The strategies include:

- Call on all hospitals during the first three months of launch, convincing pharmacy directors to stock OxyContin.

- Educate the target audiences on the benefits of OxyContin compared to other Step 2 opioids for cancer pain. The education should convince hospital staff to prioritize OxyContin as their “opioid of choice,” emphasizing the ease of use, shorter administration time, and if available, clinical studies that show improved quality of life and cost effectiveness (p. 24).

- Deliver educational lectures through the company’s speaker bureau during tumor boards, grand rounds, etc. The bureau should present data from clinical studies while educating the staff about the benefits of OxyContin.

- Conduct educational symposia that provide CME credits for physicians, nurses, and registered pharmacists. The symposia should focus on the AHCPR Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Cancer Pain, alongside data from clinical trials with OxyContin.

- Host a “special pain management day” at the top 100 hospitals that prescribe MS Contin and Duragesic, allowing clinical investigators at Purdue to train the hospital staff on OxyContin (p. 24).

The fifth site is patients and caregivers, along with social workers and volunteers. The strategies include:

- Develop educational materials, such as a patient video and assessment journal, to help patients communicate about their pain.

- Compile a “patient empowerment pack” to assist pharmacists with patient counseling. The pack would include the AHCPR patient guideline for cancer pain, a comfort assessment journal, and patient education brochure on OxyContin (p. 25).

- Implement a consumer awareness program, specific to OxyContin, to educate “about the tragedy of needless suffering that occurs in millions of cancer patients every year.” The program could be done in collaboration with the American Cancer Society or another major medical organization, and the main focus would be “you don’t have to suffer and something can be done about your pain.” In addition, the company could offer a 1-800 number that allows patients and caregivers to receive more information about managing cancer pain (p. 25).

- Support existing medical education programs like “I Can Cope” from the American Cancer Society. “I Can Cope” teaches patients and caregivers how to navigate issues surrounding cancer and its treatment, with only a minor emphasis on pain management. Still, support from Purdue, such as an educational seminar to “train the trainer,” could be viewed favorably (p. 25).

The sixth site is long-term care, where the key audience is consultant pharmacists. The strategies include:

- Develop programs and materials to help educate the key audience on pain management. The objective would be to make consulting pharmacists “experts in pain management,” who would then team care providers in long-term care facilities (p. 26).

- Offer discounts on the wholesale acquisition price of OxyContin.

- Focus the sales force on raising the awareness and brand recognition of OxyContin, contacting, in the first year, all closed-provider pharmacies within their sales territories.

Tactics

For each of the strategies above, the writers divide the tactics both “vertically” and “horizontally.” Vertically, the tactics are divided into three tiers. Tier I tactics “offer the most immediate return on investment, are essential to the launch, and must be implemented.” Tier II tactics “offer return on investment in the short term, would augment the launch, and must be seriously considered.” Tier III tactics “provide long term return on investment and should be considered if product sales exceed forecast” (p. 26).

Horizontally, the writers divide tactics into domains that specify activities, audiences, timelines, and the estimated budget. The domains include deliveries from sales reps, mail programs, journal advertisements, public relations initiatives, and convention exhibits.

To prepare for their roles as both marketers and “educators” in the launch, the sales reps would need additional training, arguably a kind of internal tactic. The writers recommend a training binder that contains relevant clinical data and information about the competition, centering on the benefits of OxyContin for healthcare professionals and patients. A “product knowledge quiz” could gauge the sales reps’ depth of knowledge (p. 56).

The second internal tactic is two days of training at a separate launch meeting. Consisting of workshops, the meeting would explore such topics as findings from clinical studies, the features and benefits of OxyContin, expected objections from prescribers, and sales aids, among other things. Additional training modules would come later (p. 56).

The writers estimate resource allocations for the tactics, along with grand totals, attempting to reinforce organizational appropriation: At the time of launch, there would be 291 sales reps, 39 managers, 6 national accounts managers, and 15 managed care account executives, and the cost of staffing each position was approximately $135,000 per year (p. 54). The first year post launch, the sales force would devote 70% of their primary calls to OxyContin, and it appears that the total sales and marketing costs would come to approximately $34 million. OxyContin was projected to turn a negative gross profit initially (-52%). But it was projected to turn a 12% profit its second year, and 67% its fifth year (pp. 54A-E, 55A-F). In short, given the communal rationality expressed in the launch plan, OxyContin had selling potential in the SAF, but company executives and managers should not expect significant profits in the near term.

Discussion

The launch plan was an effective one, in some ways an exemplary piece of TPC. In the years that followed, OxyContin became a runaway success, with sales growing from $48 million 1996 to over $1.1 billion in 2000 (Van Zee, 2009). By 2001, the volume of prescriptions made OxyContin a bestselling painkiller in the country (General Accounting Office [GAO], 2003). These market gains had not come cheaply. Between 1996 and 2002, the promotion budget for OxyContin was up to 12 times larger than the promotional budgets for its two main competitors, MS Contin and Duragesic (Van Zee, 2009). Michael’s team of writers thus had exercised considerable social skill in their SAF: casting OxyContin in a positive light, casting competitors in a negative light, and eliciting cooperation where needed. The communal rationality expressed in the launch plan had evidently struck its corporate readers as both sensible and persuasive.

Absent from the launch plan, troublingly, is a discussion of “the ethical repercussions of one’s words” (Miller, 1979, p. 617). The launch plan does contain several references to the “ethical field force” (pp. 27, 28, 55A, 55C). Yet, in those references, “ethical” indicates sales reps, not values that govern conduct. Indeed, the writers propose strategies and tactics that, at least with the benefit of hindsight, are problematic. First, the writers do not consider the ethics of promoting a Class II narcotic—the riskiest products that external governance units, like the FDA, allow—so broadly and aggressively in the SAF. Second, the writers make primary care physicians prime targets for OxyContin, a decision that has attracted extensive criticism (e.g., Hughes et al., 2019; Schottenfeld et al., 2018).

While this promotion is not excusable, the launch plan does reveal some of the underlying motivations. Among them: researchers had persuasively but wrongly argued that fears of opioid addiction were overblown (Meldrum, 2016), and so the writers of the launch plan highlight the upward titration potential. Moreover, many physicians across specialties, including primary care, were already prescribing opioids in significant numbers, so while Purdue sales reps did not necessarily light the match, they did pour fuel on the flames. Future studies might examine how innovative it was to position sales reps as not just sellers, but educators.

This too, may have been a serious ethical violation as Purdue Pharma worked to expand the WHO analgesic stepladder, blurring the lines between education and marketing. Both education and marketing were permitted, even endorsed, under industry standards at the time (International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Associations [IFPMA], 1994). However, the standards also urged “self-discipline” (IFPMA, 1994), and positioning sales reps as both sellers and educators almost certainly created conflicts of interest. Technical communicators who work in biomedical industries must be cognizant of such conflicts and, as needed, seek professional development in health literacy, bioethics, and marketing ethics. At minimum, marketing should not be disguised, and companies that do participate in educational activities must ensure that the materials are “fair, balanced and objective, and designed to allow the expression of diverse theories and recognized opinions” (IFPMA, 2019, p. 29).

Still, many healthcare workers have questioned whether the pharmaceutical industry should play such a large role in medical education. For instance, a few years before the OxyContin launch, one physician reasoned, “If you were buying a used car, would you get your information from Sam, the friendly used-car salesman?” (Waud, 1990, p. 352). He continued, “I have heard anecdotes about occasional pearls passed on by detail men [pharmaceutical sales reps], but generally, the ‘education’ is a thinly disguised selling job. And they are good at it” (Waud, 1990, p. 353) Similarly, another physician proposed, “public health would be best served by severing the pharmaceutical industry’s direct role and influence in medical education,” at least for controlled drugs, which run a high risk for abuse and diversion (Van Zee, 2009, p. 225). Positions like these are not unwarranted.

Unfortunately, Section 5.8 contains the only reference in the launch plan to potential abuse, and there are none to diversion, the illegal transfer of OxyContin to someone other than the patient. There are also few references to safety, monitoring, and potential harms more broadly. True, scientific knowledge has advanced since 1995, when Michael submitted the launch plan to his colleagues in Norwalk. But the launch plan illustrates a problematic trend of stigmatizing users themselves through reductive terms like “abusers.” In Section 5.8, for example, the writers state that pharmacists may be reluctant to stock Class II opioids, like OxyContin. “This reluctance,” the writers explain, “is based on fears that drug abusers will try to obtain these drugs for other than medicinal purposes.” The proposed solution is an appeal to financial motivations: promotional copy should emphasize that MS Contin had been an “incredible success” (p. 27). MS Contin had indeed created a sizable market for extended released painkillers, generating profits for pharmacists and helping grow their business. Pharmacists could expect, then, that OxyContin had similar market potential. However, OxyContin would have a much higher potential for misuse, and the repeated comparisons to MS Contin, in the launch plan and elsewhere, would devolve into “a reliance on faulty analogies” (Griffin & Spillane, 2012, p. 166). Furthermore, the term “abusers” could be a form of racial or class coding, contributing to later inequalities in opioid prescriptions (Parker & Hansen, 2022). The launch plan is, in these ways, an example of communication failure (cf. GAO, 2003).

Granted, the writers could not have anticipated the human misery that followed, and the final draft of the launch plan reflects a complicated mishmash of corporate influences. But the launch plan can still stand as a cautionary tale for technical communicators today. As a partial safeguard, technical communicators must elevate their professional ethics above the “concepts, values, traditions, and style” (Miller, 1979, p. 617) of the biomedical discourses that they produce. Beyond that, we must work to reimagine the boundaries of these discourses and advocate for more culturally responsive, inclusive approaches to TPC (Alexander & Edenfield; Frost, 2018; Frost et al., 2021; Green, 2021; Itchuaqiyaq et al., 2022; Walwema, 2021; Wang, 2021)—pre-launch, peri-launch, and post-launch. These efforts can support calls in the pharmaceutical industry to build cultures of trust (IFPMA, 2019).

Methodologically, this article suggests the usefulness of SAF, which I took as a three-point heuristic. The heuristic foregrounds what is going on in the SAF and what is at stake, interpretive frames that actors construct to understand each other’s actions, and what the rules of the game are. Applied, the heuristic highlighted key datapoints supporting the writers’ arguments, (perceived) opportunities related to Purdue Pharma’s positions as both incumbent and challenger, and an elaborate set of strategies and tactics centered on specific positioning statements and selling points—in short, the communal rationality expressed in the launch plan. These findings align with Guiltinan (1999), who described strategies as the “what, where, and when” and tactics as the “how” (p. 514). In product launches, companies often focus on targeting strategies, timing strategies, and strategies that showcase the innovativeness of the product, and the launch plan for OxyContin arguably exemplifies all three.

Continuing this line of inquiry, future research might examine the influence of the Purdue Pharma Partners Against Pain program, the speaker’s bureau, and the continuing education symposia described in the launch plan. Outside of Purdue, future studies might investigate, amid the ongoing crisis, the communal rationality of large distributors of opioids (such as Cardinal Health, McKesson, and AmerisourceBergen) as well as other makers of opioids. An insightful case study may be Janssen, the maker of Duragesic. After its launch, Duragesic was initially well accepted among health professions, grew steadily in market share, but was recently discontinued. Other case studies might explore what Fligstein and McAdam (2012) call “episodes of contention,” borrowing from social movement theory. Episodes of contention are characterized by innovation, a sense of uncertainty or crisis, and sustained mobilization by both challengers and incumbents, resulting in competing interpretive frames. Studies like these may, in turn, advance the notion of SAF, which, at its heart, rests on the problem of order (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, p. 12).

To further nuance the three-point heuristic, future research might investigate the interplay of mnesis (remembering and forgetting) taxis (arrangement of parts of a topic, including tables and figures) in biomedical discourses (DeTora, 2021; Stormer 2004, 2013). These rhetorical concepts can apply not just to a single document, but to a collection, allowing researchers to track changes over time and across genres. As more examples become available, we might explore how launch plans have evolved in the pharmaceutical industry. We might also explore how launch plans function in larger “genre ecologies” (Spinuzzi & Zachry, 2000), which may include clinical trial paperwork, launch meetings, promotional materials, product packaging and labeling, regulatory writings, federal hearings, scientific journal articles, and public comments.

Given the breadth of genre ecologies, these studies may require “big data” approaches, which Graham (2021) and Gallagher et al. (2019) have demonstrated helpfully. Graham (2021) did a “computational rhetorical analysis” (p. 27) of how language surrounding opioids changed after government organizations adopted the “fifth vital sign” metaphor, sampling from top medical journals. Gallagher et al. (2019) analyzed patterns in sentiment, themes, geolocations, and comment frequency in a corpus of approximately 450,000 public comments, all posted to the New York Times website. Either approach may provide additional insight into biomedical discourses, communal rationality, and SAF dynamics, including those in product launches.

In future research, we might also draw on “tactical TPC” streams of scholarship (see Kimball, 2017; Randall, 2022). For instance, post-launch studies might investigate how non-organizational actors, such as patients and caregivers, exercise social skill to present themselves credibly, navigate risk, and (successfully or not) try to get the help and resources that they need. Molloy (2020), among others, has broken ground in this area, examining how patients in vulnerable circumstances construct rhetorical ethos amid race, class, and gender biases. TPC researchers might extend this research to stigma surrounding opioid use disorder and overdosing, adopting culture-centered approaches designed to reduce inequities (Dutta, 2008; see also DeTora & Robinson, 2022; Frost et al., 2021). Culture-centered approaches may help address the disparities that Welhausen (2022, 2023) found in public reports of the opioid crisis, generating deeper insights into how victims have been inequitably (re)presented and treated. We might also examine the evolving social significance of oxycodone, which, as the launch plan suggests, was an important medication for those suffering from HIV/AIDS. Studies in this vein are particularly important because as the historian David Courtwright (2001) has observed, “what we think about addiction very much depends on who is addicted” (p. 4).

These are only a few paths forward, and granted, the United States opioid crisis is not the only pressing public health issue that merits greater attention in TPC scholarship. But efforts to address the opioid crisis must remain a high priority however long it lasts, being “one of the largest and most complex public health tragedies that [the United States] has ever faced” (Gottlieb, 2019). The launch plan for OxyContin provides a valuable point of entrée.

References

Agboka, G. Y. (2014). Decolonial methodologies: Social justice perspectives in intercultural technical communication research. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 44(3), 297-327.

Agboka, G. Y. (2021). What is on the traditional herbal medicine label? Technical Communication and Patient Safety in Ghana. Technical Communication, 68(1), 4-19.

Alexander, J. J., & Edenfield, A. C. (2021). Health and wellness as Resistance: Tactical folk 12 medicine. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(3), 241-256. DOI: 13 10.1080/10572252.2021.1930181

Alpert, A., Evans, W. N., Lieber, E. M., & Powell, D. (2022). Origins of the opioid crisis and its enduring impacts. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(2), 1139-1179.

Anekar, A. A., & Cascella, M. (2021). WHO analgesic ladder. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

Aziz, A. (1974). Article titles as tools of communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 4(1), 19-21.

Batova, T. (2019, July). Cultural dimensions, consumption of opioid pain medications, and designing educational information products. In 2019 IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (ProComm) (pp. 154-161). IEEE.

Bell, H. D., Walch, K. A., & Katz, S. B. (2000). “Aristotle’s pharmacy”: The medical rhetoric of a clinical protocol in the drug development process. Technical Communication Quarterly, 9(3), 249-269.

Bivens, K.M. (2018). Reducing harm by designing discourse and digital tools for opioid users’ contexts: The Chicago Recovery Alliance’s community-based context of use and PwrdBy’s technology-based context of use. Communication Design Quarterly, 7(2), 17-27.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP.

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Boyd, M. C., Marra, L. A., & Swanson, S. J. (1997). Strategic planning in a nonprofit organization: STC’s Rochester chapter thinks strategically. Technical Communication, 44(4), 418.

Congressional Budget Office. (2021, April). Research and development in the pharmaceutical industry. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57126

Cornelissen, J. P., & Werner, M. D. 2014. Putting framing in perspective: A review of framing and frame analysis across the management and organizational literature. The Academy of Management Annals, 8(1): 181–235.

Courtwright, D. T. (2001). Dark paradise: A history of opiate addiction in America. Harvard University Press.

Cuppan, G.P., & Bernhardt, S.A. (2012). Missed opportunities in the review and revision of clinical study reports. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 26(2), 131-170.

Davis, J. J. (1999). Imprecise frequency descriptors and the miscomprehension of prescription drug advertising: Public policy and regulatory implications. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 29(2), 133-152.

DeTora, L. (2021). New ways of reading: Making sense of complex biomedical writing using existing guidelines. In J. Schrieber & L. Meloncon (Eds.), Assembling critical components: A framework for sustaining technical and professional communication (pp. 221-241). University of Colorado.

DeTora, L. M. (2017). What is safety?: Miracles, benefit‐risk assessments, and the “right to try.” International Journal of Clinical Practice, 71(7), e12966.

DeTora, L., & Klein, M. J. (2020). Invention questions for intercultural understanding: Situating regulatory medical narratives as narrative forms. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 50(2), 167-186.

DeTora, L., & Robinson, T. Culture-centered approaches to rhetorical research: Considering domestic violence as a site for intersectional interventions. In L. Meloncon & C. Molloy (Eds.), Strategic Interventions in Mental Health Rhetoric (pp. 51-67). Routledge.

Ding, D. D. (2004). Context-driven: How is traditional Chinese medicine labeling developed? Journal of technical writing and communication, 34(3), 173-188.

Dreher, K. (2018, July). Plain language in text and talk: Community health outreach and the opioid addiction crisis. In 2018 IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (ProComm) (pp. 136-137). IEEE.

Dutta, M. J. (2008). Communicating health: A culture-centered approach. Polity.Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2012). A theory of fields. New York: Oxford UP.

Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2011). Toward a general theory of strategic action fields. Sociological Theory, 29(1), 1-26.

Frost, E. A. (2018). Apparent feminism and risk communication. In A. Haas & M.F. Eble (Eds.), Key theoretical frameworks: Teaching technical communication in the twenty-first century (pp.23-45). University Press of Colorado

Frost, E. A., Gonzales, L., Moeller, M. E., Patterson, G., & Shelton, C. D. (2021). Reimagining the boundaries of health and medical discourse in technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(3), 223-229. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2021.1931457

Gallagher, J. R., Chen, Y., Wagner, K., Wang, X., Zeng, J., & Kong, A. L. (2020). Peering into the internet abyss: Using big data audience analysis to understand online comments. Technical Communication Quarterly, 29(2), 155-173.

Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems in social theory: Action, structure, and contradiction in social analysis. Berkeley: University of California Press.

General Accounting Office (GAO). (2003). Prescription drugs: OxyContin abuse and diversion and efforts to address the problem. Washington, DC. Publication. GAO-04-110.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gilding, M., & Pickering, J. (2011). May contain traces of biotech”:(re) defining the biotechnology field in Australia. In Proceedings of Australian Sociological Association Conference (p. 1). Available at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ 2a05/3a23a11a1e4c8dc2afb6f533da9715dd81a9.pdf

Gottlieb, S. (2019, February 26). Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D. on the agency’s 2019 policy and regulatory agenda for continued action to forcefully address the tragic epidemic of opioid abuse. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-agencys-2019-policy-and-regulatory-agenda-continued

Graham, S. S. (2015). The politics of pain medicine. University of Chicago Press.

Graham, S. S. (2021). The opioid epidemic and the pursuit of moral medicine: A computational-rhetorical analysis. Written Communication, 38(1), 3-30.

Graham, S. S., & Herndl, C. (2013). Multiple ontologies in pain management: Toward a postplural rhetoric of science. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22(2), 103-125.

Graham, S. S., Kim, S. Y., DeVasto, D. M., & Keith, W. (2015). Statistical genre analysis: Toward big data methodologies in technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 24(1), 70-104.

Green, M. (2021). Risking disclosure: Unruly rhetorics and queer(ing) HIV risk communication 6 on Grindr. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(3), 271-284. 7 https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2021.193018

Guiltinan, J.P. (1999). Launch strategy, launch tactics, and demand outcomes. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 16(6), 509-529.

Hughes, J., Kale, N., & Day, P. (2019). OxyContin and the McDonaldization of chronic pain therapy in the USA. Family Medicine and Community Health, 7(1). doi:10.1136/fmch-2018-000069

International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Associations (IFPMA). (1994). IFPMA code of pharmaceutical marketing practices. International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association

International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Associations (IFPMA). (2019). Code of practice: Upholding ethical standards and sustaining trust. Available at: https://ifpma.org/publications/ifpma-code-of-practice-2019/

Itchuaqiyaq, C. U., Edenfield, A. C., & Grant-Davie, K. (2022). Sex work and professional risk communication: Keeping safe on the streets. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 36(1), 1-37.

Jacox, A.K., Carr, D.B., Payne, R., Berde, C.B. (1994). Management of cancer pain. Clinical practice guideline no. 9. Rockville, Md.: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. (AHCPR publication no. 94-0592).

Kessler, M. M., & Graham, S. S. (2018). Terminal node problems: ANT 2.0 and prescription drug labels. Technical Communication Quarterly, 27(2), 121-136.

Kimball, M. A. (2017). Tactical technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(1), 1-7.

Lakoff, G. (2014). The all new don’t think of an elephant!: Know your values and frame the debate. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Maat, H. P., & Klaassen, R. (1994). Side effects of side effect information in drug information leaflets. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 24(4), 389-404.

Maat, H. P., & Lentz, L. (2011). Using sorting data to evaluate text structure: an evidence-based proposal for restructuring patient information leaflets. Technical Communication, 58(3), 197-216.

Meier, B. (2018). Pain killer: an empire of deceit and the origin of America’s opioid epidemic. Random House.

Melby, L., Obstfelder, A., & Hellesø, R. (2018). “We tie up the loose ends”: Homecare nursing in a changing health care landscape. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 5, 1-11. DOI:

Meldrum, M. L. (2016). The ongoing opioid prescription epidemic: Historical context. American Journal of Public Health, 106(8), 1365.10.1177/2333393618816780 journals.sagepub.com/home/gqn

Miller, C. R. (1979). A humanistic rationale for technical writing. College English, 40(6), 610-617.

Molloy, C. (2019). Rhetorical ethos in health and medicine: Patient credibility, stigma, and misdiagnosis. Routledge.

Montague, J. F. (1971). New and improved techniques of medical communications. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 1(2), 115-126.

Natanek, R., Schlegel, C., Retterath, M., & Eliades, G. (2017, September 6). How to make your drug launch a success: Three things that winning pharmaceutical companies do write. Bain & Company. https://www.bain.com/insights/how-to-make-your-drug-launch-a-success/

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987. https://www.congress.gov/bill/100th-congress/house-bill/3545/text

Pakes, G. E. (1993). Writing clinical investigator’s brochures on drugs for a pharmaceutical company. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 23(2), 181-189.

Parker, C. M., & Hansen, H. (2022). How opioids became “safe”: Pharmaceutical splitting and the racial politics of opioid safety. BioSocieties, 17(4), 577-600.

Randall, T. S. (2022). Taking the tactical out of technical: A reassessment of tactical technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 52(1), 3-18.

Sato, C.C.M. (2018). The social construction of the psychotropic drugs market in Brazil [doctoral thesis]. Available at: http://www.ppa.uem.br/documentos/005-claudia-cristina-macceo-sato.pdf

Schottenfeld, J. R., Waldman, S. A., Gluck, A. R., & Tobin, D. G. (2018). Pain and addiction in specialty and primary care: The bookends of a crisis. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 46(2), 220-237.

Schrimpf, M. (2018). Medical discourses and practices in contemporary Japanese religions. Medicine–Religion–Spirituality, 57.

Smith, R. A., Girth, A. M., & Hutzel, M. (2021). Assessing organizational role and perceptions of programmatic success in policy implementation. Administration & Society, 53(10), 1512-1546.

Griffin, O.H., & Spillane, J.F. (2012). Pharmaceutical regulation failures and changes: Lessons learned from OxyContin abuse and diversion. Journal of Drug Issues, 43(2), 164-175.

Spinuzzi, C. (2010). Secret sauce and snake oil: Writing monthly reports in a highly contingent environment. Written Communication, 27(4), 363-409.

Spinuzzi, C., & Zachry, M. (2000). Genre ecologies: An open-system approach to understanding and constructing documentation. ACM Journal of Computer Documentation (JCD), 24(3), 169-181.

Stormer, N. (2004). Articulation: A working paper on rhetoric and taxis. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 90(3), 257-284.

Stormer, N. (2013). Recursivity: A working paper on rhetoric and mnesis. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 99(1), 27-50.

Teston, C. B., Graham, S. S., Baldwinson, R., Li, A., & Swift, J. (2014). Public voices in pharmaceutical deliberations: negotiating “clinical benefit” in the FDA’s Avastin hearing. Journal of Medical Humanities, 35(2), 149-170.

Van Zee, A. (2009). The promotion and marketing of OxyContin: Commercial triumph, public health tragedy. American Journal of Public Health, 99(2), 221-227.

Ventafridda, V., Saita, L., Ripamonti, C., & De Conno, F. (1985). WHO guidelines for the use of analgesics in cancer pain. International Journal of Tissue Reactions, 7(1), 93-96.

Walwema, J. (2021). The WHO health alert: Communicating a global pandemic with 2 WhatsApp. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 35(1), 35-40. 3 https://doi.org/10.1177/10506519209585074

Wang, H. (2021). Chinese women’s reproductive justice and social media. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(3), 285-297. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2021.1930178

Waud, D. R. (1992). Pharmaceutical promotions—a free lunch? New England Journal of Medicine, 327(5), 351-353.

Welhausen, C. A. (2022). Precarious data: Crack, opioids, and enacting a social justice ethic in data visualization practice. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 65(1), 50-69.

Welhausen, C. A. (2023). Visualizing a drug abuse epidemic: Media coverage, opioids, and the racialized construction of public health frameworks. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, https://doi.org/10.1177/00472816221125186

Michael J. Madson, Ph.D. is an assistant professor at Arizona State University, where he teaches courses in technical communication and user experience. He also runs a scientific writing course for the Medical University of South Carolina, where he was previously a faculty member in the Center for Academic Excellence / Writing Center.

Madson’s research focuses on drug safety (especially opioids and cannabis), wayfinding in healthcare facilities, and the training of health professionals. His articles in these areas have recently appeared in Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, HERD: Health Environments Research & Design, Medical Teacher, and Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. With Routledge, he has published two edited collections, Teaching writing in the health professions: Perspectives, problems, and practices (2021/2022) and Composing health literacies: Perspectives and resources for undergraduate writing instruction (2023). He is the founder and organizer of the annual Conference on Teaching Writing in the Health Professions, which currently convenes in early June.