By Scott Abel | STC Senior Member

In the digital age, change happens quickly. This column features interviews with the movers and shakers—the folks behind new ideas, standards, methods, products, and amazing technologies that are changing the way we live and interact in our modern world. Got questions, suggestions, or feedback? Email them to scottabel@mac.com.

In the digital age, change happens quickly. This column features interviews with the movers and shakers—the folks behind new ideas, standards, methods, products, and amazing technologies that are changing the way we live and interact in our modern world. Got questions, suggestions, or feedback? Email them to scottabel@mac.com.

In this issue of Meet the Change Agents, Scott Abel, The Content Wrangler, interviews Carmen Simon, PhD, a cognitive scientist who is changing how the world communicates. Through her work with Rexi Media, a presentation design and training company she co-founded, Dr. Simon helps America’s most visible brands craft memorable messages by focusing on how the brain works. She holds doctorates in both instructional technology and cognitive psychology and is a recognized expert in presentation design, delivery, and audience engagement. Her sought-after keynote speeches unveil science-based techniques for getting others to see your way, remember your way, and go your way.

Scott Abel: Dr. Simon, thanks for speaking with us today about the importance of neuroscience in professional communication. Before we dive deep into the world of brain science, tell our readers a little about who you are and what you do for a living.

Scott Abel: Dr. Simon, thanks for speaking with us today about the importance of neuroscience in professional communication. Before we dive deep into the world of brain science, tell our readers a little about who you are and what you do for a living.

Carmen Simon: I am a cognitive scientist, which means I research mental functions such as attention, memory, and decision-making. I convert the findings into practical guidelines we can all use to keep the world evolving. Mastering flight, creating electronic devices, and flying into space were decisions made possible by getting the attention of others and deciding to take action. Consider the bionic eye implant that allowed a blind man to see the outlines of his wife finally, and reach out to grab her hands, which he could see for the first time in a decade. To make this happen, many scientists had to get others’ attention, create strong memories, and make it easy to decide to say yes to new procedures.

SA: What is neuroscience and what brought you to study it?

CS: Neuroscience is the field that studies the structure and function of the brain. In the past decade, a lot of progress has been made in decoding the brain. While we don’t know the entire brain, using advanced brain imaging technologies, we now know a lot more than we’ve ever known. It’s exciting to start applying some of these findings to the way we communicate. When we want to persuade others, we are mostly addressing a set of neurons. Understanding how those neurons form and retain connections and put the body in motion makes it more interesting to craft communication because you’re using evidence, not opinions.

We have to be cautious though because people are now adding “neuro” to so many things that it’s becoming tough to differentiate the field from pseudo-science. There is a lot of neuro-nonsense out there, popularized particularly by brain-imaging technologies. For example, just because a scan shows only a few highlighted areas in the brain, it does not mean that the other parts are not active (hence the “we only use 10% of our brain” myth). Try it for yourself. Next time you’re in a group and want to leave a great impression, use the word neuroplasticity or talk about a study in which subjects were asked to look at [insert any object here] and “their insular cortex lit up.” The insular cortex is a region of the brain that lights up in about a third of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies, so your accuracy will be pretty high. On the other hand, there are situations where we don’t need neuroscience to form conclusions. I read about a functional MRI (fMRI) study on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in which the authors concluded, “PTSD is a brain disease and concrete proof of human suffering.” I am sure we can observe human suffering without fMRI studies. Always look to combine neuroscience with cognitive and behavioral findings to form a well-rounded view of techniques we can use to improve communication.

Scott Abel: I love watching you give presentations. You are a fantastic presenter, and you practice what you preach. And, audiences respond. When I took your two-day workshop, I recall the most shocking thing I learned from the presentations was that people forget up to 90% of what we present. Why is this? How does neuroscience help us know this is true?

CS: The percentage comes from a theory and formula in use for more than 100 years, called the forgetting curve. Whenever people come across information without the intent to remember it, they tend to forget most of it after a few days. This curve has an exponential shape, which means that we tend to forget quickly at first and slower later. In other words, if I attend a presentation and all I remember is that “last year, Americans forfeited 169 million days of vacation,” this small tidbit will tend to stay with me long-term.

The advice I have for presenters is to figure out which “10%” they would like others to remember and use the rest of the 90% to bring the essential material into focus. Too often, presenters leave this process to chance. As a result, audience members are unable to recall a particular message. Instead, they form random memories, which have negative consequences in business. They lead to rambling and anemic content that creates unnecessary confusion, prompting those we hope to reach to ask additional follow-up questions. Random memories cause us to revise and re-create content to overcome the confusion.

SA: You talk a lot about the need to craft presentations and other communications that direct attention and guide behavior. What do you mean by this?

CS: Communicators aspire to create compelling, memorable content. But, no matter how good our communication skills may be, without understanding how the brain works, we’re less likely to succeed.

Memory is about retention; about not forgetting. One of the reasons people forget is because they don’t pay attention in the first place. Attention paves the way to memory.

Letting audiences direct attention on their own is risky. Most people won’t make the effort to look where you think they should, or pay attention in ways you believe they might. That means that discovering and understanding your content depends on their willpower, which is in limited supply.

My advice is to guide people’s attention instead of leaving it to their own devices. We can do this with words (“Look here”) or provide physical stimulation that cannot be ignored, such as bright or large or colorful shapes in a space of neutral or small ones.

SA: What tactics can we use to ensure our content is as memorable as possible?

CS: I’ve identified 15 variables we can use to influence other people’s memory. The most natural one is repetition. But even with repetition, we have to be careful not to cross the line into annoyance. For the brain to detect a pattern, we must repeat something at least three times. After that, consider combining a repetitive message with a reward that your audience’s brains find satisfying.

For example, we may hear a message such as “Just Do It” many times, so Nike has to be creative and link it to rewards and update those rewards before the brain habituates. In Hong Kong, for example, they’ve integrated Nike products into experiences where participants complete missions such as running, playing football, walking a pet, or attending a dance class. Each of these activities earns them points they may exchange for accessories, clothing, or even tickets to sporting events. The lesson is to associate repetition with activities or ideas that deepen the connection with the products or content. Anyone can repeat a message and promise a prospect or customer an iPad for engaging with them, but that won’t help you develop a closer relationship with them or make them feel like an insider.

SA: In your book, “Impossible to Ignore: Creating Memorable Content to Influence Decisions” you introduce a groundbreaking approach to creating memorable messages that are easy to process, hard to forget, and impossible to ignore. And, you do so with a simple three-step plan designed to help us craft compelling content. Can you talk a little about these three steps and what we’re trying to accomplish during each?

CS: To answer this, we must look at memory from a different angle. Here is something to consider. What are the three most significant memory problems you experienced last week? A series of research studies have found that 60-80% of memory problems we have are related to forgetting to execute on a future intention. Yesterday, you may have intended to give someone a call, send a particular e-mail, or pick up your dry cleaning, and only remembered these today.

We have good intentions, but often forget to execute them. Even when we remember, if the reward is not compelling enough to get us to act, we don’t. Our audiences are no different. They listen to us, and they may agree that what we say is helpful. But, even after they hear our message, even if they remember part of what we said, they might not do anything about it. We can address that by changing our approach to how we view memory.

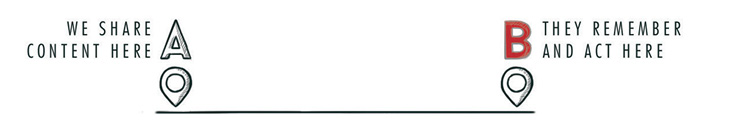

Think of memory as a practical way of keeping track of the future, not the past. Imagine that we share content at Point A, and we hope people remember and act on it sometime in the future, at Point B. This “future” can be as close as two minutes, two days, or two weeks from now, or longer. It’s sensible to ask, “What is happening in people’s lives and what do they intend to do at Point B?” If we know this already at Point A, we can prepare at Point B to become part of people’s memories and intentions when it counts.

A practical and profitable way to look at memory is from a prospective—not retrospective—angle. Prospective memory, which means acting on future intentions, is what keeps you in business (see Figure 1).

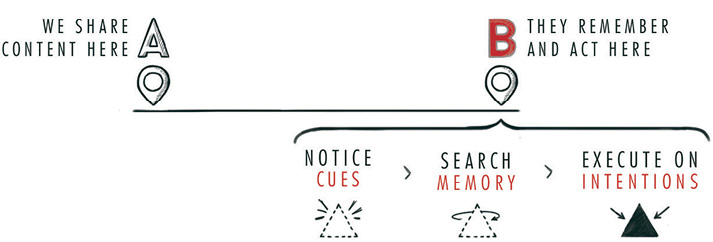

Research reveals that when people act on future intentions successfully, they complete these three steps, sometimes within fractions of seconds:

- Notice cues linked to intentions;

- Search their memory for something related to those cues and intentions, and if something is rewarding enough…

- They execute (see Figure 2).

Now consider your content. Imagine you must help your audiences go through the process described. Using the prospective memory model, at Point A, prime the audience with proper cues. Then, assist them to keep in long-term memory what is important. And finally, make it easier for them to execute on intentions at Point B. My book “Impossible to Ignore” provides practical guidelines designed to help you stay on people’s minds long enough for them to act in your favor.

SA: Which is better for memory? Variety or sameness?

CS: We need both. To have memory, we have to have conscious attention. To sustain attention, we must have variety; otherwise, the brain habituates quickly when the stimulus does not change.

For example, a PowerPoint slide in a virtual presentation, which stays unchanged for minutes at a time, is an invitation to multitask. While variety is critical to sustaining attention, we need sameness for several reasons. First of all, the brain craves patterns. Sameness helps with that. When we form patterns, we save cognitive energy, and the brain looks at those messages favorably. Sameness also enables something to stand out, and therefore commands extra attention, which leads to the building of a memory trace.

You may remember a MasterCard commercial that listed a few items that would cost money and ended with something that didn’t. For example, hot dogs, popcorn, sodas: $27, autographed baseball: $50, real conversation: priceless. By using this “template” in many subsequent commercials, the MasterCard message provides us with sameness and a familiar feeling, while the variety of the items keeps us rewarded and paying attention.

SA: Many technical communicators create modular components of content that we repurpose across multiple sets of information. In this case, modularity makes it possible for us to assemble chunks of content automatically into deliverables. The primary benefits to the organizations we work for are increased efficiency and decreased cost. Can chunking content provide additional benefits to those with whom we seek to communicate?

CS: Chunks are juicy to the brain. Because they typically come in small bites, our brain uses less energy to process them. However, it’s important to make sure the audience’s brain is provided with a bigger picture—context—to help them make sense of the small bites. This approach is necessary for two reasons: 1) A bigger picture adds context and meaning, which can form longer-lasting memories than brief exposure to small content chunks. And 2) Memory relies on associations. How modular components of content link together is as important as the design of the pieces themselves.

SA: Visuals are important in many types of communication. What advice can you provide to help us avoid one of our biggest challenges: Overcrowding the screen with far too much information?

CS: Overcrowding can be an issue. But, even screens full of content can contribute to forming memories. Imagine a complex diagram, let’s say something depicting the architecture of a software application. When we expose our audience’s brains to something like this, they have the opportunity to form two types of memory traces: verbatim memory and gist memory.

Verbatim means remembering something word-for-word, such as labels included in the chart. Gist means retaining the general meaning of what happened. So the question to ask when including a lot of materials on a screen is: what do I want viewers to remember? Is it critical that they retain some things verbatim or is it enough just for people to get the gist? If verbatim is important, then graying most of the chart out and highlighting only some areas can help. If the gist is important—let’s say it’s critical for people to realize that something is complex—then the advice is to associate it with a strong meaning and move on to the next idea quickly. Ironically, complexity will sustain attention better than simplicity because it tends to be more interesting. Simplicity can be very boring after a while. Just make sure not to abuse complex content.

SA: There are a variety of factors that impact attention. What does neuroscience teach us about how colors influence what we notice?

CS: To answer this question, we can look at research findings that help us understand how humans see. The retina converts light into an electrical signal, which the optic nerve delivers to the brain. On their journey to the brain, images are separated into various pathways based on motion, depth, colors and forms, and then reassembled in the brain.

Contrast is a good technique when using colors because they allow your viewers to perceive shapes. Let’s imagine for a moment “The Two Sisters,” by Renoir, a painting depicting two girls on the terrace of a French restaurant. One girl is wearing a bright red hat, the other a blue one, and they are both sitting in front of green plants and by a basket of colorful wool yarn. True to impressionist style, we can see the visible brushstrokes, which means we can detect the contrast better between colors and the artist can portray reality in a more vivid way. Next time you look at a Web site or a television ad, notice how your attention and comprehension of what’s going on depend on the use of color contrast.

It’s not necessary to use a particular color over another, but rather to create enough contrast between colors, so specific elements of content have a chance to stand out. Red, for example, is a bold color that has power. It has guts. But its strength depends on what’s around it.

We can attract attention with physical properties, such as colors, but this technique doesn’t build memories. To place something more durable in people’s minds, we need to attach meaning.

For example, you may forget the yarn in Renoir’s painting, but not if it’s linked to meaning. One could wonder: Why do we see a basket of wool balls, typically meant for an indoor scene, outside, on a restaurant terrace? Some suggest that Renoir may have responded to a critic who described his paintings as “a weak sketch seemingly executed in wool of different colors.” He decided to answer that critic and not make it so subtle because the wool basket completes a perfect triangle with the girls’ hats. For your next communication artifact, ask this question: Am I tying psychical properties such as color with meaning to create stronger recall?

SA: I’m afraid our time is up. I’d like to thank you for making time to talk to me today. Are there any resources you can recommend to readers who would like to learn more about neuroscience and communication?

CS: Most resources we choose to give our attention have a motivational driver behind them. My dad recently passed away, and before he died, he was in a coma—the “vegetative state” about which you may have heard. My motivation right now is to learn more about what happens in the brain during such state because the answers can give us insight into understanding the concept of self, consciousness, and perhaps what it means to be human. I’m reading a book called “Neuro-Philosophy and the Healthy Mind” by Georg Northoff. Advancements in neuroscience consistently teach us about the human condition, and this can have enormous implications for medicine, psychology, and our general well-being.

CS: Most resources we choose to give our attention have a motivational driver behind them. My dad recently passed away, and before he died, he was in a coma—the “vegetative state” about which you may have heard. My motivation right now is to learn more about what happens in the brain during such state because the answers can give us insight into understanding the concept of self, consciousness, and perhaps what it means to be human. I’m reading a book called “Neuro-Philosophy and the Healthy Mind” by Georg Northoff. Advancements in neuroscience consistently teach us about the human condition, and this can have enormous implications for medicine, psychology, and our general well-being.

SA: Thanks, Dr. Simon. I appreciate your time and valuable contributions to the discipline of neuroscience and its application to professional communication.

CS: It’s been a pleasure. It will be great to see the readers applying these insights and go beyond the typical neuroplasticity or insular cortex neuro-babble, using solid guidelines that can help us improve the way we communicate and impact how people remember what we say.