By Kirk St.Amant | STC Fellow

This column examines how cognitive factors can affect technical communication and design processes. Email the editor at stamantk@ecu.edu.

This column examines how cognitive factors can affect technical communication and design processes. Email the editor at stamantk@ecu.edu.

Every second, we are bombarded by more information than our brain can process. Yet, our minds can quickly sift through that data, identify what is important, and act on it. How is this possible? The answer involves how our minds organize sensory input—a process that affects perceptions of usability.

Cognitive Processes

Cognition involves how the brain processes information, which affects how humans assess usability. When we encounter an object, our minds engage in a three-part process to:

- Recognize – Identify what the item is;

- Categorize – Establish what the object does or how it can be used; and

- Operationalize – Determine how to use that object to accomplish a task in the current situation. It all begins with recognition—a process involving short-term memory.

Object Recognition

When we encounter something new, we hold that item in our short-term memory and compare it to the entries we have in a mental database of objects we’ve encountered before. Specifically, we compare the features of that new item to the features of objects we already know. If the new object looks enough like an entry in this database, we identify it as that kind of item. If, for example, something looks like our mental model for “hammer,” we’ll identify it as a hammer.

Short-term memory, however, is very limited. This means when we compare new objects to our mental models, we don’t compare every possible aspect. Rather, we only focus on certain characteristics. Specifically, we focus on those characteristics we consider unique to a particular item.

Our experiences, for example, have taught us hammers are comprised of a long, thin handle and one end that has a flattened surface for pounding objects. These become the factors we focus on when reviewing new items to determine if they are a hammer. If a new object contains these features, we’ll:

- Identify it has a hammer;

- Access our mental database to determine what hammers do (i.e., pound objects); and

- Review our surroundings to determine how to use that hammer in that context (e.g., to pound a loose board into place).

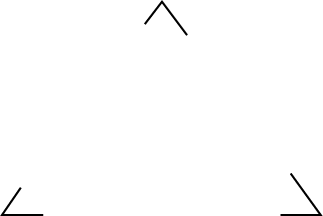

Focusing on certain features versus all features prevents us from overloading our short-term memories. It also explains how we can identify items when presented with limited sensory information. Figure 1, for example, contains only certain features, yet most of us can identify the shape as a triangle.

This is because the figure contains the key features our minds associate with identifying triangles.

Identification and Usability

Identification is central to usability. If we don’t recognize what something is, we won’t know how to use it. If, for example, we don’t recognize something is a hammer, chances are we won’t know we can use it to pound down nails. Usable designs are those that allow users to identify what an item is so that they can determine what it does and how it can be used in a particular setting. This process applies to everything from the tools we find in a toolbox to the apps we find on a mobile phone.

The key to effective identification involves reducing the information the brain needs to process. If I design an icon for “phone call” to look like the model your mind has for “phone call icon,” you’ll quickly identify it and know how to use it. If that icon does not mirror your mental model, you’ll struggle to determine what the item is and what it does. Doing so involves filling the short-term memory with large amounts of sensory input as you review all features of the item, because you don’t know which are key to identification. This load on our short-term memory is why we often become focused on and confused by new objects. Such factors affect how easily individuals can determine how to use an item.

Designing for Identification (and Usability)

Technical communicators can use this identification process to create usable designs for different audiences. The key is determining the features an audience associates with identifying certain things. To do so, technical communicators need to ask users specific questions about the mental models they use to identify items. This can be done through interviews or focus groups where users respond to these questions:

- Can you describe an [X] to me?

- How do you know it is a/an [X]? or What features make it an [X]?

- What do you use it for? or What do you do with this item?

The objective is to determine the characteristics individuals associate with the item. It also establishes the minimum common characteristics needed to identify that item.

Per the final question, one needs to confirm the members of a group will use an identified item in a certain way. Such clarification is important, for individuals could effectively identify an object, but associate it with different uses (e.g., using a screwdriver to turn screws vs. to open a sealed paint can). By comparing responses, technical communicators can identify those features an audience associates with identifying and using a particular thing.

Technical communicators can use this information to create initial designs. They should then use follow-up interviews or focus groups to test these designs by asking these questions:

- What is this item? – Determines if it is correctly identified;

- How do you know it is a/an [X]? – Determines features used to identify the item;

- Would you modify this design? If so, how? – Determines if revisions are needed to facilitate identification; and

- How do you use this item? – Confirms common perceptions of how to use the item.

Technical communicators can use the resulting information to modify (and re-test) designs as needed.

The speed with which the human brain works is stunning. By understanding how humans process information, technical communicators can create designs that better address user expectations. An understanding of how the mind identifies objects can guide such processes and lead to more usable designs.