By Thomas Barker | STC Fellow

In this column, I’ll look back to an early academic conversation about personas and reader analysis. It’s sometimes useful to reflect on hidden gems of scholarship in technical writing—for example, that ideas of human-centered design—and specifically how our current thinking, especially about personas—might have derived from the examination of government policy documents back in 1983.

What Is a Persona?

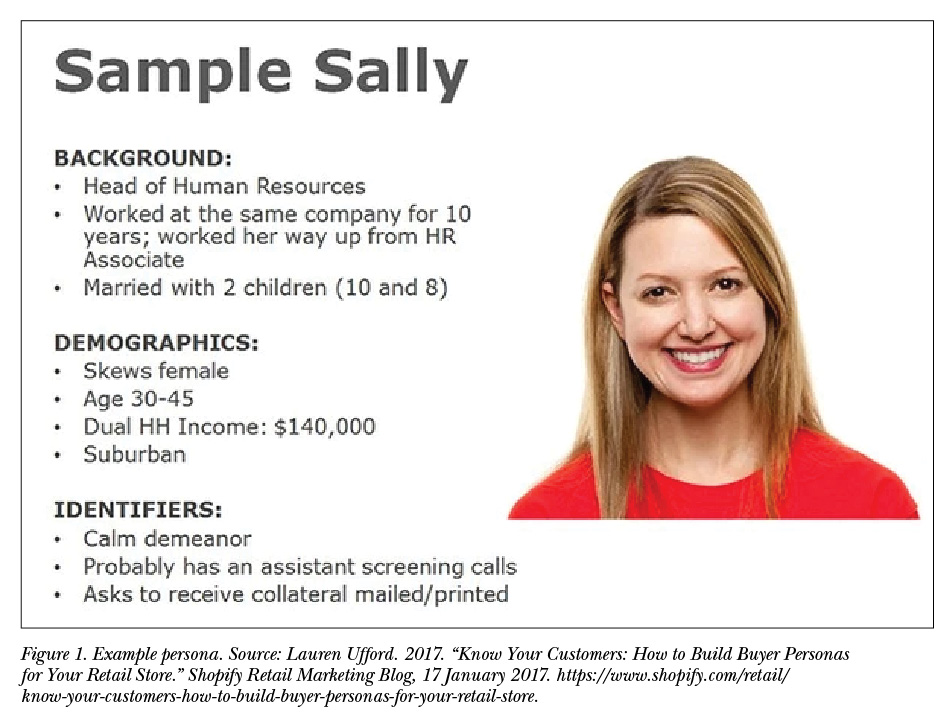

First, a definition. A persona, as discussed here and shown in Figure 1, refers to a marketing and general document design tool consisting of a description of an often very narrow market or user segment. Specific and highly detailed persona descriptions, as argued by Alan Cooper in The Inmates Are Running the Asylum, have a special power over general, abstract descriptions: their very specificity suits them for general use.

The persona is like a “super profile.” We know about profiles, such as those we create in social media and other applications. They are everywhere today. To turn your profile into a persona, however, it would need to be an amalgam of other profiles with similar motivations, needs, and data about buying habits—a super profile made up of details supported by data.

The magic of the persona happens when the super profile triggers design decisions and outcomes, resulting in a product or pitch that grabs everybody described by the persona. Products like roller luggage and sidewalk ramps have become commonplace but were originally designed for very specific users. This is the magic of personas to deliver a one-size-fits-all from a one-size-fits-one approach.

The Now

Jeanne L. Higbee and Emily Goff’s Pedagogy and Student Services for Institutional Transformation: Implementing Universal Design in Higher Education is all about the magic of the persona. The authors refer to it as universal design (UD). Here, we again see the utility of not a general, but a specific, design: accommodation for people with disabilities. It’s all over higher education, according to Higbee and Goff. Here’s how they explain it:

Universal Design promotes the consideration of the needs of all potential users in the planning and development of a space, product, or program—an approach that is equally applicable to architecture or education. It also supports the notion that when providing an architectural feature—or an educational service, for that matter—to enhance accessibility and inclusion for one population, we are often benefiting all occupants or participants.

The “one population” in the quote above refers to the world of disability services. These are services for the visual-, hearing-, and mobility-impaired community. Persons with special limitations (or gifts) point us—designers, writers, marketers—toward solutions for people without those limitations and gifts.

Higbee and Goff explain persona magic in this way:

One of the most often cited examples is the curb cut, which is used by people on roller blades or skateboards, parents pushing strollers, travelers hauling luggage, people making deliveries with hand carts, and others, as well as by people with disabilities. Similarly, many people benefit from the provision of automatic doors, elevators, door handles instead of knobs, and so on.

The roots of this idea of the curious general utility from specific design come from design theories in psychology. Not only can personas lead to great design, they look human, and their “presence” as interesting people helps create a communicative bond among the design team members.

One thing you find in scholarship subsequent to Cooper, as in the work of John Carroll, is the term “scenario.” In writings about design, scenario has come to mean a set of consequential actions, steps for using something, including a cast of characters. The concept of scenario, I argue, is prevalent in persona theory. I submit as evidence an early—and very neglected—paper on scenarios that “had it right” long before the term persona was in common use.

The Then

Linda S. Flower, John R. Hayse, and Heidi Swarts tried something very unusual in the late 1970s when they designed their research study:

- They wanted to study the readers’ experience, not grammar—what actual behaviors do readers show when faced with a desert of definitions and a tangle of cross references (for example, “See section 8c, part b”)?

- They looked at functional documents in the workplace (instructions, proposals, reports) and used talk-aloud protocol analysis to determine how readers make sense of deadly, dense prose.

- They studied revision and how readers “revise” in their heads to make sense by asking readers to talk aloud while reading. (Genius!)

The study resulted in a principle: the scenario.

We hoped that this research would suggest a practical, powerful principle for revising Federal regulations and, by implication, other functional documents. And indeed it did. We call this principle the “scenario principle,” which states that functional prose should be structured around a human agent performing actions in a particularized situation.

Note that this work reflects the time when it was first published, and we should remember that a publication date of 1980 meant that the work might have started up to two years earlier. Indeed, the piece reflects the time: the emphasis on readability formulas like the Flesch Index, the Writers’ Workbench, and other tools used in government and still in vogue in technical writing. The act of revision was also a popular focus in technical writing instruction at the time, whereas now the focus is more on readers’ processing.

These reflections of the time, however, are not the real brilliance in this article. The brilliance, I argue, comes from what the researchers found. When they recorded people talking about how they plodded through dry loan requirements, these perceptive researchers noticed that readers took descriptions and turned them into stories. For example, where the text defined what qualified as a “print service” (ownership and independence from the borrower), the reader revised it in terms of everyday actions. It’s the kind of shop where you “have something that you need printed, you bring it in, they print it up.”

The Power of Stories

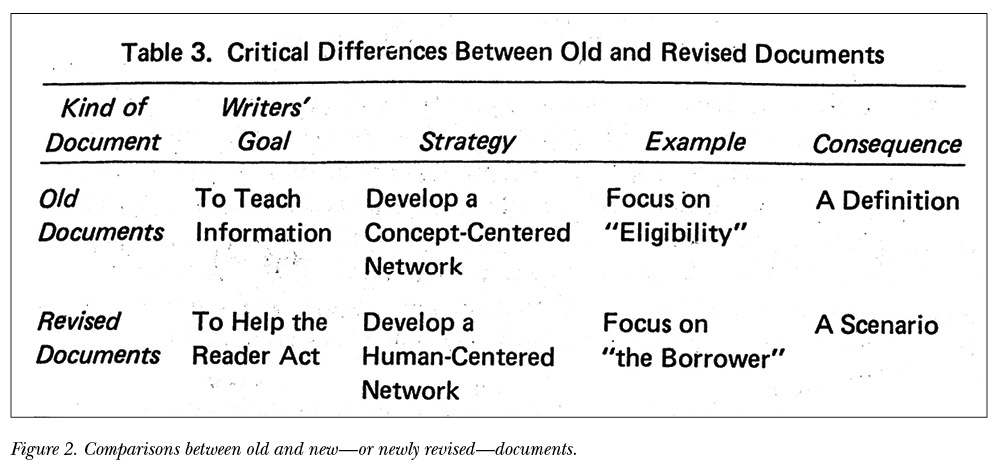

Turning something into a story, it turns out, is one way that readers revise dense prose in their minds. They don’t just replace big words with little ones or develop meanings as a whole. They personalize it—give it an actor, action, and goal or outcome. They create real, concrete imaginary situations based on tasks. From this idea, the authors spin out a number of comparisons between old and new—or newly revised—documents, all deriving from the fundamental polarity of describe/act, dehumanized action to engaged actors, and so on, as shown in Figure 2.

The authors describe their discovery in terms of the kinds of associations made (that is, dots connected) by their “talk-aloud” readers. They observe that the old version of the documents was “designed to create a network of information centered around concepts and key terms.” They follow up by saying:

The revised regulations, on the other hand, try to create a human-centered network of information focused on human agents and their actions, such as borrowers who live in the United States and promise to repay loans; it is this strategy which we have been calling the scenario principle.

Conclusion

Today, we’re all about stories. In research, for example, participative modes have led to storytelling as a way of knowledge making. Stories have the power to evoke, to stir, to affect, to motivate—a power that is extensively exploited in the data-rich world of social media advertising. Stories are magic, and how that magic works is illustrated by the “then and now” of these two articles: that a specific story—about me, my origins, my work goals—fits in a story, in a scene with people in it. The story of people with disabilities gives us insights into all of our workplaces, showing how they can be improved for all.

Those gems from the shelf show us a lot about our origins from our literature and scholarly conversations of ideas about people. They speak from the past about writing, technical communication, and ways to bring a human focus to functional information.

This column focuses on a broad range of practical academic issues from teaching and training to professional concerns, research, and technologies of interest to teachers, students, and researchers. Please send comments and suggestions to column editor Thomas Barker at ttbarker@ualberta.ca.

This column focuses on a broad range of practical academic issues from teaching and training to professional concerns, research, and technologies of interest to teachers, students, and researchers. Please send comments and suggestions to column editor Thomas Barker at ttbarker@ualberta.ca.

References

Cooper, Alan. 1999. The Inmates Are Running the Asylum. Indianapolis: Macmillan.

Flower, Linda S., John R. Hayes, and Heidi Swarts. 1980. Revising Functional Documents: The Scenario Principle. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University.

Higbee, Jeanne L., and Emily Goff. 2008. Pedagogy and Student Services for Institutional Transformation: Implementing Universal Design in Higher Education. Minneapolis: Center for Research on Developmental Education and Urban Literacy.