By Eric Korankye

As an academic from an underrepresented Ghanaian background, I think about how most pedagogies in the field of technical communication are U.S.-centric (based on U.S. culture and concepts) with little or no room for cultural diversity and integration of international knowledge. Instructional materials, textbooks, research modules, dominant discourse, scholarly sources, and recommended scholarship from the U.S. are centered, while canons and frameworks from non-American backgrounds are marginalized. Thinking about how current cultural contexts have affected the way we conceptualize and engage the intersections of language, access, and power in the teaching of technical communication, it is quite evident how exclusive U.S.-centric education is inadequate to respond to the growing demands of technical communication.

The Student Perspectives column provides insights, experiences, research, and more from students across technical communication. We’re proud to introduce new voices, inject new ideas, and give the practitioners of tomorrow a platform to begin publishing their thought leadership today! Column editor Ryan Weber teaches technical communication at the University of Alabama in Huntsville and hosts the podcast 10-Minute Tech Comm. Contact him at rw0019@uah.edu to submit or pitch a column idea.

The work of technical communicators serves multicultural audiences—users and the public from diverse cultural backgrounds whose perspectives matter in technical communication decisions; therefore, studies in the field should incorporate cultural diversity. Social justice education emphasizes how institutions can better serve traditionally marginalized students and push back against structures that replicate the systems of injustice, unequal access to education, and one-size-fits-all educational practices in many institutions.

In my contribution to amplifying marginalized voices and showcasing the academic scholarship from my background, I seek to explore the possibilities of just futures for teaching technical communication in the United States: designing pedagogies that integrate intercultural and international knowledge from Ghana, Africa. The discourse of technical communication and rhetoric in Ghana is replete with experienced researchers, writers, scholars, and curriculum designers whose works have historical and transcendent relevance in international discourse in technical communication. Why is such knowledge, as well as knowledge from other non-American backgrounds, not privileged?

A Ghanaian rhetoric that succinctly describes the work of technical communication is the role of the linguist in the palace of the Ashantis, an ethnic group in Ghana. Culturally, the Ashanti chief or king does not speak directly to his audience (that is, his subjects or visitors); he speaks through the linguist, who interprets the chief’s message—which is often couched in highly dense proverbial and parabolic language—to ensure the understanding of everyone. The subjects also pass their message through the linguist to the chief. Usually, the linguist refines the language to make sure it is culturally appropriate, rich, reverential, and not contemptuous. The linguists are not only mediators or interpreters; their active listening skills, understanding of the full context of the communicative situation, fluency of language, and vast cultural knowledge make them cocreators of the discourse in the palace. This role is similar to the work of the technical communicator, who provides clear, simple documentation to explain a company’s products or services to end users. If technical communication education could incorporate experiential knowledge such as this from marginalized backgrounds, the field would expand.

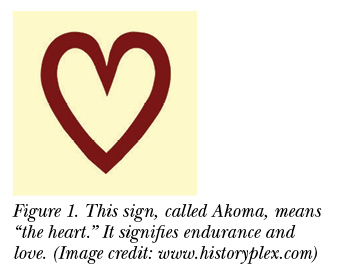

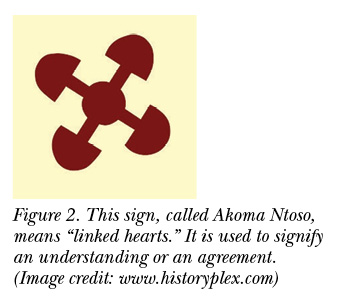

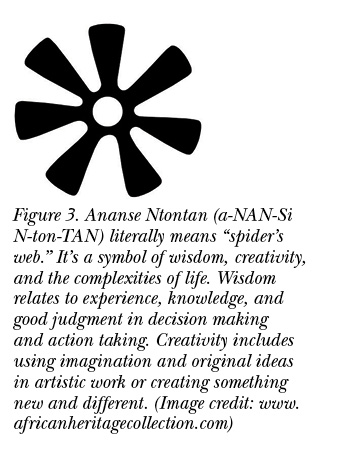

Another prominent communicative art in Ghanaian rhetoric is the use of Adinkra symbols—the marks on the traditional cloth of the Ashantis. The various signs and symbols of the Adinkra express African philosophy and wisdom. This indigenous communication medium conveys messages whose meanings can be decoded by people who have Adinkra literacy. Before the introduction of Western systems of writing, these symbols were created by people of Akan ethnicity to preserve cultural values, beliefs, and experiential knowledge. Some examples of these Adinkra symbols are illustrated in Figures 1, 2, and 3.

These symbols are comparable to the use of signs by political groups, advocacy groups, and religious bodies that carry evocative messages. The work of technical communicators is embedded in rhetoric and culture. Therefore, the integration of these communicative arts into the teaching of technical communication would widen students’ perspectives about the importance of signs and symbols and their cultural impact in communication.

Embracing language and cultural diversity in the classroom is one strategy that educators need to consciously adopt to turn such diversity into a valuable pedagogical resource for their teaching and learning. Global studies continue to diversify “learning spaces due to rapidly shifting student demographics and increased efforts to internationalize curriculum to ready graduates for increasingly diverse work environments and the evolving global economy,” according to Punita Lumb and colleagues. Often, however, programs in technical communication or educational institutions lack this awareness of diversity, and this affects the academic identities of students from underrepresented backgrounds who pursue American education. As Godwin Y. Agboka, Han Yu, and Gerald Savage have found, “Indeed, language, access, and power are at the heart of our ever-expanding, increasingly globalized work which includes working against injustice through intercultural and international knowledges.”

We have the responsibility to address inclusivity in and out of the classroom. We need to be intentional about implementing cultural mediation pedagogy in our technical communication classrooms. This pedagogy will have a ripple effect on our education system and society as a whole and will challenge educational and social injustices. The rhetoric, literature, and scholarship from backgrounds of students traditionally underrepresented and underserved should be incorporated in syllabus design. This approach will help decolonize the classroom and ensure global citizenship and equity education for student success.

In Ghanaian rhetoric, a concept that illustrates the communal strength and unison that I seek to incorporate into this discussion is the Akan proverb, “Praye, se woyi baako a ebu, wokabom a emmu.” To wit, “The broom is sturdy and unbreakable, because its strands are tightly bound.” Literally, when you remove one strand of a broom, it breaks easily, but when you put strands together in a bunch, they do not break. Essentially, I mean to say, “In unity lies strength.” When technical communication embraces communal knowledge sharing from different national cultures, we build a stronger community of technical writers, teachers, students, and practitioners.

Eric Korankye (enkora1@ilstu.edu) is a master’s student in technical writing and rhetoric at Illinois State University. He is an online teacher of English, a rhetor, an editor, a proofreader, a writer, and a poet. His research interests include rhetoric in technical communication, translingual and multimodal pedagogies, and language and cultural inclusivity in higher education. He is a Sub-Editor in the Parliamentary Service of Ghana and the Executive Editor of West African Magazine in Ghana.

References

Agboka, Godwin Y. 2013. “Participatory Localization: A Social Justice Approach to Navigating Unenfranchised/Disenfranchised Cultural Sites.” Technical Communication Quarterly 22 (1): 28–49.

Lumb, Punita, Yasmin Razack, Shaila Arman, and Tatiana Wugalter. 2019. “Innovating Curriculum: Integrating Global Citizenship and Equity Education for Student Success.” In Strategies for Fostering Inclusive Classrooms in Higher Education: International Perspectives on Equity and Inclusion (Innovations in Higher Education Teaching and Learning, Vol. 16), edited by Jaimie Hoffman, Patrick Blessinger, and Mandla Makhanya, 111–127. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Yu, Han, and Gerald Savage. 2013. Negotiating Cultural Encounters: Narrating Intercultural Engineering and Technical Communication. Wiley-IEEE Press.