by Saul Carliner | STC Fellow

In 1994, STC supported a study that was conducted in Western Canada on the value of technical communicators. Although the study found that organizations felt that technical communicators added value and could describe specific instances in which particular organizations felt they benefitted from technical communicators, the authors of the study could not name any broad, general ways that technical communicators add value.

Perhaps they were asking the wrong question.

It’s not that adding value isn’t important, but the type of value sought in the Western Canada and other studies in the 1990s primarily explored on the benefits derived after organizations publish technical content. And because few organizations actually track whether their published technical content ultimately results in a financial benefit (such content is from an old release; most of them are focused on future releases), their actual assessments of the value added by technical communicators are usually formed through the countless ongoing interactions that occur while developing that content.

That’s why technical communicators need to pay more attention to the perceptions of their customers (the internal or external groups that pay for technical communication services) than to the value added. This article identifies two categories of drivers of perceptions, suggests a way to address them with customers, and closes with one other issue raised by this study.

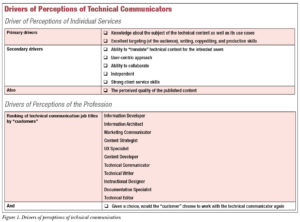

Primary Drivers of Perceptions

This study identified two primary drivers that technical communication managers and their teams should specifically pay attention to.

- Knowledge about the subject of the technical content, as well as its use cases, is important. Participants in this study not only expected it, but many voiced frustration when technical communicators lacked these skills.

- Excellent targeting, writing, copyediting, and production skills are important. Although we technical communicators want to primarily be recognized for our ability to conceptualize material, clients also seem to value our ability to produce “professional” documents, which seems to refer to grammatically and stylistically correct, and visually attractive materials, which some people refer to as wordsmithing.

In fact, that latter role is how roughly half of the customers see the role of the technical communicator. This suggests that technical communicators should first determine with which type of customer they are working when starting a project and adjust their expectations of the role accordingly. If customers merely use technical communicators to wordsmith documents, technical communicators will need to broach the extent to which they have liberty to offer suggestions on the content.

Secondary Drivers of Perceptions

Following those primary drivers are several secondary drivers.

- The ability to “translate” technical content for the intended users. In this case, the translation refers to translation from technical language to plain language, not necessarily from English to other languages, like German and Mandarin.

- Taking a user-centric approach, which is an extension of the previous driver.

- The ability to collaborate. Participants commented that they expect team players when working with technical communicators.

- Participants indicated that they need technical communicators who can learn technical content quickly and accurately with little to no assistance from Subject Matter Experts; they expressed frustration with technical communicators who fail to quickly grasp material.

- Strong client service skills, such as proactive and polite communication, and the appearance of being motivated to work on the project. Participants in this study specifically noted their frustration at working with technical communicators who did not appear to be interested in or motivated by their work.

The data suggest, too, that the published content drives perceptions of technical communicators. Most participants primarily commented on the appearance of the materials, but some commented on the impact of the content on the intended users.

Using These Drivers to Address Perceptions with Customers

One of the challenges with this set of drivers is that, although it is somewhat feasible to generate it from a descriptive survey that is widely distributed like this one, it is difficult to survey customers within an organization about their perceptions of individual technical communicators and technical communication groups.

So technical communicators need to gauge perceptions in other ways. One of the best is for debriefings between the manager of the technical communication group and customers or the ombudsperson in the customer organization. Good times to hold these debriefings include the post-mortems of projects and through annual reviews. During these debriefings, technical communication managers should explicitly address these drivers with the ombudsperson and address concerns that arise in the conversation.

One Other Issue Arising in this Study

The drivers mentioned in this article primarily refer to perceptions of the services provided by technical communicators, but technical communicators also have broader concerns about perceptions of the profession itself.

The ranking of job titles offers numerous insights into the similarities and differences in perceptions of different fields and roles between customers and technical communicators. That the two parties chose the same roles for the top two and bottom two ranked roles suggests some alignment of perceptions among the two groups.

But the survey also offers broader insights into the ongoing debates over the job titles that might best benefit technical communicators, on which ones we should not expend any energy, and on which ones the field needs to address concerns.

In terms of the job titles that could benefit the field, we should pay more attention to the titles information developer and content developer, which customers rank the highest of all job titles in the field, even higher than UX specialist and content strategist, titles that technical communicators prefer.

In terms of job titles on which we should not expend energy, the data suggests that the effort to distinguish between a technical writer and a technical communicator has resulted in negligible differences in perceptions at best. If using the term technical communicator is intended to raise the status of the profession, the data suggests that it has not made much of a dent.

In terms of the roles on which the profession needs to pay attention, the results suggest that we should examine why people rank documentation specialist and technical editor so low to determine why and what, if anything, can be done to strengthen perceptions of these roles.

But perhaps the most important driver of perception of technical communication is whether “customers would choose to work again with technical communicators if given a choice. This aligns with the Net Promoter Score used widely in business, but also aligns with the top level of evaluation in a model of evaluating technical communication products that I proposed in 1998 in Technical Communication.

Figure 1 summarizes the drivers of perceptions.

SAUL CARLINER (saulcarliner@hotmail.com) is a professor of educational technology at Concordia University in Montreal, a past editor of the IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, and a Fellow and Past President of STC.