By Saul Carliner | STC Fellow

An overview of the top credentialing options for technical communicators.

What can you do to become qualified for a sought-after position and to remain employable in positions similar to the one you currently hold?

Certainly, the traditional qualification—the degree—continues to be available. But alternatives to the degree have emerged, as have other types of credentials that recognize knowledge and skills gained through experience, like the experience gained in your work positions.

This article explores the top three options for gaining credentials in an emerging landscape of new credentials. The options are not unique to technical communication; they apply to most skilled work. This article starts, however, at the end: the goal for acquiring credentials.

The Goal: Demonstrate Competence

The primary goal for acquiring credentials is to become qualified for jobs of interest and to remain employable after you are hired. Maintaining employability is especially important in the current labor market, because the competencies required of workers change, even when people already hold the jobs. Competency refers to the ability to perform something successfully. To retain their jobs, workers need to maintain their competency.

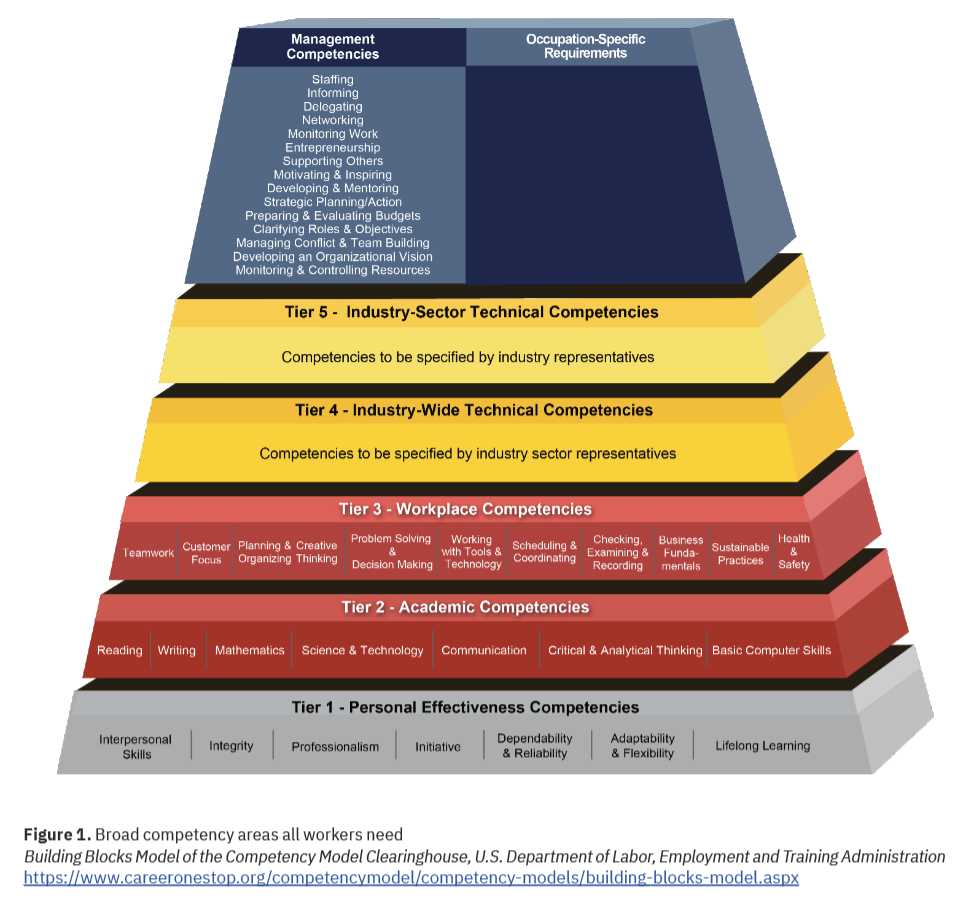

According to the Competency Model Clearinghouse project of the U.S. Department of Labor, the competencies workers need fall into these categories:

- Personal effectiveness competencies, such as interpersonal skills, integrity, and initiative. These are developed from the youngest ages through a combination of experiences at home, in school, at work, and through life.

- Academic competencies, such as reading, writing, critical and analytical thinking, and basic digital skills, which are developed through K–12 education and further enhanced through higher education.

- Workplace competencies, such as teamwork, customer focus, and problem-solving and decision-making skills, which are developed through a combination of schooling, life experiences, and work experiences.

Industry-wide technical competencies, which refer to competencies needed within an industry segment, like hospitality, information technology, and manufacturing, and are usually developed through work experiences and job-related training.

Industry-wide technical competencies, which refer to competencies needed within an industry segment, like hospitality, information technology, and manufacturing, and are usually developed through work experiences and job-related training.- Industry-sector technical competencies, which refer to competencies needed within a certain part of an industry—such as the aircraft segment of the transportation industry—and are developed similarly to industry-wide technical competencies.

- Management competencies, such as staffing, strategic planning, and monitoring and controlling resources, which are learned in formal education—higher education or training—and honed on the job.

- Occupation-specific competencies, which are the focus of most job-related education and credentialing, and usually developed in academic and training classrooms and honed on the job.

The Competency Model Clearinghouse created the model in Figure 1 to represent the relationships among these competencies.

Competencies are developed in different ways—some through formal education and training, others through experience. Certification and experience also provide recognition and validation of competence.

Competencies are developed in different ways—some through formal education and training, others through experience. Certification and experience also provide recognition and validation of competence.

Reaching the Goal: Credentialing

You can achieve goals related to developing one or more of these competencies through credentialing efforts. This section explores three of the most common options for doing so: certificates, certification, and experience.

Option 1. Certificates

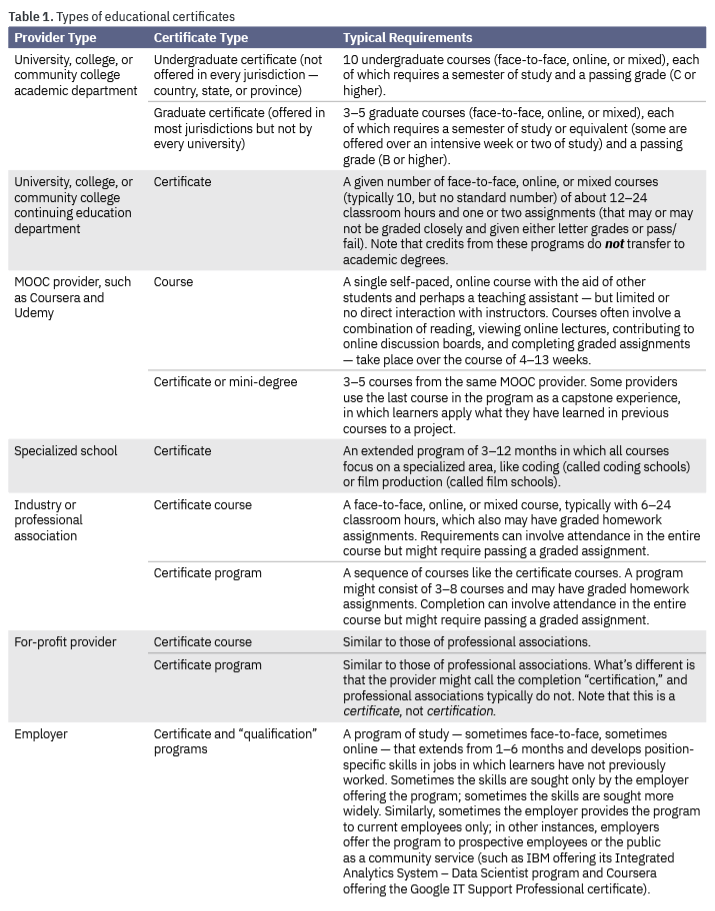

A certificate acknowledges the successful completion of educational requirements. But the nature of those requirements varies widely, from completion of one course with several sessions to completion of a sequence of courses.

Table 1 summarizes the most common types of certificates available and who provides them.

Option 2: Certification

Many people and organizations call the awarding of a certificate certification.

But it’s not.

Whereas certificates represent the completion of educational requirements, certification represents the validation of expertise by a third party. Whereas a certificate is similar to a degree, certification is more like a license. The primary difference between certification and a license is that a license is required to work legally in a field. Certification is voluntary. Although certification might be a preferred qualification, employers cannot legally require it.

Because they focus on demonstrating skills and knowledge, certifications provide a means of recognizing workers for competence they have developed either on their own or on the job. Most certifications consist of one or more of the following:

Because they focus on demonstrating skills and knowledge, certifications provide a means of recognizing workers for competence they have developed either on their own or on the job. Most certifications consist of one or more of the following:

- Entry qualifications, which represent the requirements to apply for the certification and usually require completion of a stated amount of education and minimum amount of time in a type of job.

- Knowledge exam, which is a test of the key definitions and concepts underlying the area of certification and strategies for applying those definitions and concepts in practice.

- Skills demonstration, which validates that the applicant can perform the skills being certified and occurs through either a demonstration or review of a portfolio of completed work.

- Expiration date, which indicates the period that the certification is valid. Most certifications offer a path to extending the validity, which often requires additional training or taking the certification exam again.

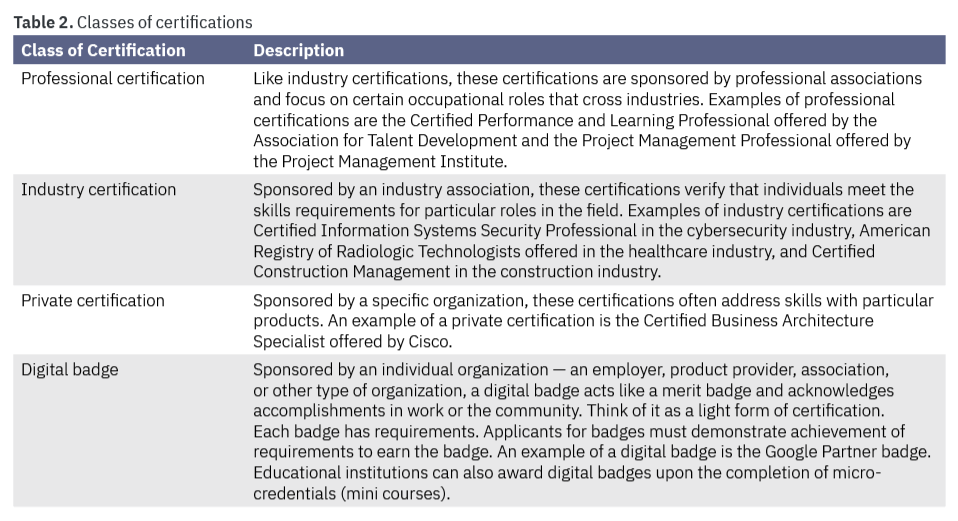

Table 2 describes the major types of certifications.

People who hold certifications typically earn the right to add letters after their name. Those letters represent a designation. For example, one of the co-authors of my book Career Anxiety: Guidance Through Tough Times is certified in project management and lists “PMP” (Project Management Professional) by their name.

People who hold certifications typically earn the right to add letters after their name. Those letters represent a designation. For example, one of the co-authors of my book Career Anxiety: Guidance Through Tough Times is certified in project management and lists “PMP” (Project Management Professional) by their name.

Badges are handled differently. Badge holders typically include their badges in their LinkedIn profiles, on social media, or on a résumé.

Option 3. Experience (Which Matters as Much as Education)

Experience becomes increasingly important—as important as formal credentials—in maintaining employability. As British researcher Michael Eraut noted, the primary strength of formal education is developing conceptual knowledge and the basic skills needed for an occupation (2004). On-the-job experience provides insights into how to use those skills in a job setting and develops judgement regarding not-so-clear-cut issues, such as how to handle problems and how to approach decisions that are not documented in textbooks or job procedures. On-the-job experience also provides insights into where practices depicted as rigid rules in textbooks are more flexible in practice. Employers value that knowledge developed on the job.

Another reason that employers value experience is that on-the-job experience exposes workers to a variety of competencies that are covered in neither academic curricula nor alternate (training) curricula. Some pertain to working with the latest technologies and work techniques, which are increasingly launched in real work settings and find their way into academic and training curricula only after reaching a critical mass in the workplace.

On-the-job experiences also provide workers the opportunity to work with a wide variety of people under a variety of conditions. Some of this, of course, is related to coworkers of different backgrounds from that of the worker. Some of this involves learning to interact with people in different roles, such as internal and external customers, internal and external suppliers, and other employees and contractors.

On-the-job experiences provide workers, too, with opportunities to develop expertise within certain industries and organizations, experiences that most academic curricula overlook entirely. Most academic programs avoid focusing on specific industries, so their graduates have the broadest possible opportunities post-graduation. For most workers, the only way to develop expertise in an industry sector is to work in it.

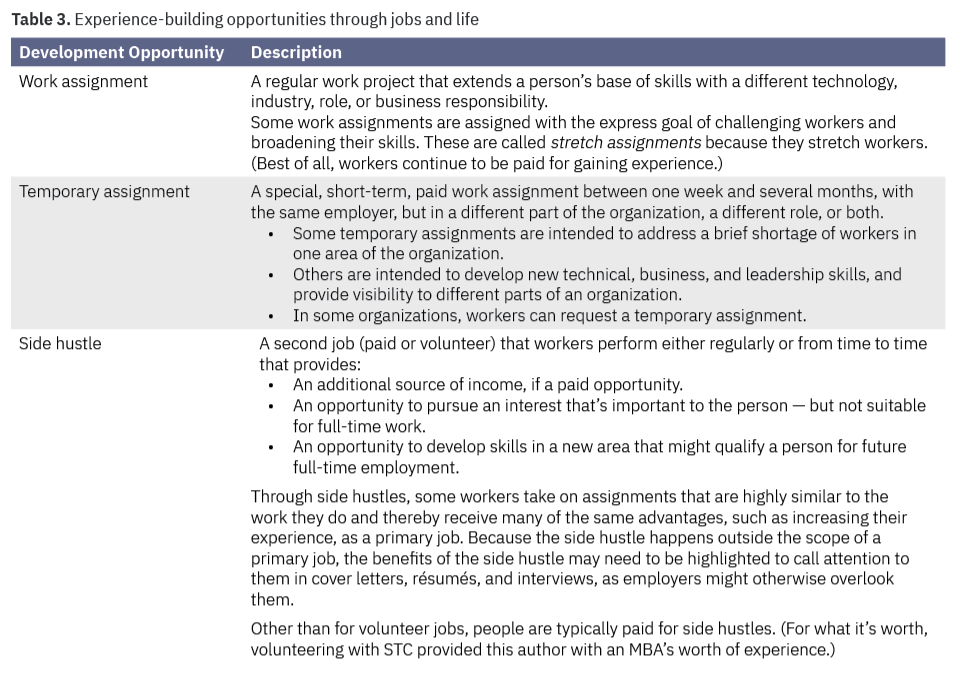

In other words, the only way to build parts of the complete set of competencies needed for long-term employability is through on-the-job experiences. Fortunately, many options exist for developing experience through your job and life. Table 3 summarizes several of these options.

Figuring Out Your Path

Technical communicators certainly have many opportunities to acquire credentials to gain employment and remain employable. However, the question facing them is, which one(s) is/are best for me?

Issues to consider when making the decision should include:

- What is feasible given the demands of my job and outside commitments (like family responsibilities)?

- What is economically feasible? Will my employer assist me? If not, what I am willing to spend?

- Which credentials can I acquire within the context of my job? (This suggests that when choosing jobs and job assignments, do so strategically, looking at how the assignments can strengthen your employability.)

- Which credentials will employers in my area recognize? What do the job ads say? What does my professional network say?

The rest of this special issue explores specific opportunities available to technical communicators for strengthening their credentials.

Reference

- Eraut, M. 2004. “Informal learning in the workplace.” Studies in Continuing Education 26, no. 2:247–273.

SAUL CARLINER (saulcarliner@hotmail.com) is a professor in the Department of Education at Concordia University in Montreal, and its chair. Among his books is Career Anxiety: Guidance Through Tough Times (2021, International Career Press) (written with Margaret Driscoll and Yvonne Thayer), from which this article is adapted with permission by the authors. He is a Fellow and past president of STC.

SAUL CARLINER (saulcarliner@hotmail.com) is a professor in the Department of Education at Concordia University in Montreal, and its chair. Among his books is Career Anxiety: Guidance Through Tough Times (2021, International Career Press) (written with Margaret Driscoll and Yvonne Thayer), from which this article is adapted with permission by the authors. He is a Fellow and past president of STC.