By Jennifer Wilhite, with Aalyna Gonzales, Cavan Nicolas Christie, Genesis Romero, Mariana Cuanalo Martinez, Marie Hall, Ellette Mendez, and Mark Dexter-Quinn

Why high school dual-credit instructors should teach technical writing basics

Technically College

“I love the bold way technical writing is visually, very professional and straightforward. Though overwhelming at times, it causes a good first impression. Both technical writing and literary writing hold their beauty, but if there is one thing I learned from Dual Credit English it’s that they are not the same.”—Mariana Cuanalo Martinez

While technically juniors in high school, the students in dual-credit English classes are also ID-carrying students of our local community college. High school students who take on dual-credit English classes need a foundation in technical writing, which includes proposals, research papers, and formal reports. Research projects that mandate technical writing experiences in dual-credit classes not only introduce students to rigorous genres, but also give them a chance to develop writing skills their future degrees and professions will mandate.

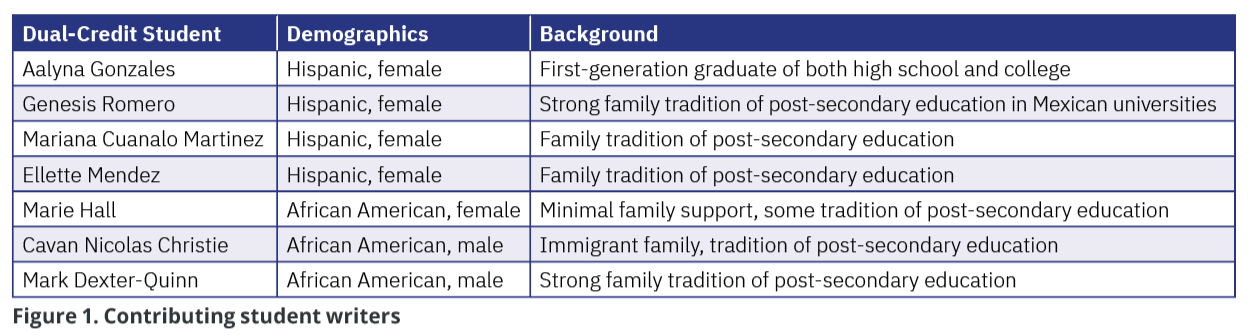

While writing this article, I taught at a low-income, early college high school on the Texas-Mexico border. Sixty percent of that student body identifies as English as a second language learners and 100 percent are eligible for free lunch programs. In order to synthesize the experiences of the college-hybrid students, I asked volunteers from my fall 2021 and spring 2022 1302 English Composition classes to answer reflective questions about their dual-credit writing experiences (see Figure 1 for student list).

When applying for universities, dual-credit students know “admissions boards may be impressed that students have already shown the ability to succeed at college-level course work.”¹ Cavan was parentally coerced into the program, but along with Ellette, Marie, Mariana, and Mark, he agrees that early college not only prepares students for the rigors of advanced academic study, but also gives them a head start into post-high-school life. Genesis and Mark specifically appreciate the financial stresses alleviated by early college, which is free for students. Many of our students, like Aalyna, will be the first in their families to graduate from any level of post-secondary education.

Technically Writers

Enrollment in dual-credit programs is on the rise in the United States. Studies indicate that students who take dual-credit classes are more likely to persist and complete post-secondary degrees.2 However, often students entering dual-credit programs are not ready for the rigors of college writing.

The most salient challenge dual-credit writing students face is that although they are still high school students, their professors expect them to perform at college levels. Many students begin their dual-credit classes “without the basic content knowledge, skills, or habits of mind they need to succeed.”3 Cavan reflects, “Prior to me leaving middle school, I thought I was a good writer. Little did I know I was far from it.” When Aalyna started dual-credit writing classes, she says all she knew about academic writing was “how to avoid plagiarism, write a basic (non-impressive) thesis statement, and that a paragraph should be about four sentences.”

Teaching technical writing skills in dual-credit classes also builds the confidence of young students. Genesis was apprehensive at first, but soon found her writing self-efficacy growing as she “experience[d] lots of recoding and interpreting data.” Mariana also expressed a lack of self-confidence in her technical writing skills, which was overcome as she found that the skills she learned in our first-year composition class did transfer to her other classes.

Technically Professors

Because we work on and are part of a high school campus, dual-credit professors are often more involved in the lives of their students. Dual-credit professors can be, according to Genesis, “more accessible and friendly” and available for students academically as well as personally. Dual-credit students are technically college students and their teachers are technically professors; however, the dual-credit program allows for interactions not always supported by a college or university environment. We can give high school support while maintaining rigorous college standards. For instance, on a college campus, professors do not always directly supervise students while they write. The dual-credit model provides a space where professors can model writing expectations. As students write in class, they are able to ask questions and respond to answers immediately. Professors can monitor real-time writing and provide instant feedback that corrects writing errors before they become writing habits.

In order to prepare students for technical writing in their academic disciplines, I assign a semester-long writing project. Students select topics from their current or intended discipline or other technical-writing topics of high interest. They have written papers about topics including how to counterfeit money, what it takes to become a neurosurgeon, and how negative home lives adversely affect academic achievement. Encouraging students to select their own topics enables them to practice conducting research in the disciplines that interest them. Sometimes these projects reinforce a student’s desire to pursue a particular career; other times, these projects help students realize they are not as enamored with the discipline or topic as they thought.

After completing a series of reflective free writes, students write a formal proposal that presents their topic for approval. Once their topics are approved, students begin their research process with databases like EBSCO and JSTOR but are encouraged to listen to podcasts, watch TED Talks, and seek a variety of valid sources. As they learn, they craft questions that will become their formal research questions. When they have a solid set of research questions, students design surveys and interviews that target appropriate research participants. Although not a popular part of the project, this effort helps students learn how to analyze survey results and transcribe interviews. The project culminates with a research paper and a formal presentation of what they have learned on their research journey.

Throughout this process, dual-credit composition professors can support their emerging college writers in a variety of ways:

- Allowing self-selected topics and encouraging students to explore high-interest topics and potential career fields.4

- Supporting students with direct in-class technical writing instruction like teacher-modeling, examples of finished products, and focused individual instruction.1

- Challenging students to use the technical writing process to “develop both deeper knowledge of the content and the more general logical and analytical thinking skills valued at the postsecondary level.”3

- Working with professors at their supporting college and local universities to remain current with professional and technical writing expectations.1

Technically Prepared

As the students reflected on their dual-credit writing experiences, they realized that these projects taught them to use writing to let readers “see a piece of our mind” (Genesis). Marie knows that “these classes are not the easiest, but they are worth it in the end” and can help with academically preparing for further university, which, as Mark says, enables students to “enjoy [their] college years with less stress.” Ellette learned that “being able to write in different ways can open doors to new opportunities” both academically and professionally.

Dual-credit classes can alleviate some of the costs of college, but also help students become more academically mature. Mariana writes, “Because of dual credit, I learned to trust myself, and that the world doesn’t owe you anything.” Cavan shared some family wisdom, “My grandma always told me that a good education can never be taken away. So that would be my greatest reward out of the program. I now have something that no one can touch, and best of all I earned it.” Teaching dual-credit students technical writing skills in first-year composition gives them authentic college experiences like these, and prepares them for the technical writing projects that await them at the university and in their professions.

References

- Tinberg, H., and J. P. Nadeau. 2013. What happens when high school students write in a college course? A study of dual credit. The English Journal 102, no. 5: 35–42.

- Blankenberger, B., E. Lichtenberger, and M. A. Witt. 2017. “Dual Credit, College Type, and Enhanced Degree Attainment.” Educational Researcher 46, no. 5: 259–263.

- Venezia, A., and L. Jaeger. 2013. “Transitions from High School To College.” The Future of Children 23, no. 1: 117–136.

- Ribéreau-Gayon, A., and D. d’Avray. 2018. “Interdisciplinary research-based teaching: Advocacy for a change in the higher education paradigm” in Shaping Higher Education With Students: Ways to Connect Research and Teaching: 139–149.

Since 2006, JENNIFER WILHITE has taught all levels of high school English and currently teaches dual-credit English at Friona High School in Friona, Texas. She also tutors graduate students. Her research focuses on teaching pedagogies at the secondary and college levels.

Since 2006, JENNIFER WILHITE has taught all levels of high school English and currently teaches dual-credit English at Friona High School in Friona, Texas. She also tutors graduate students. Her research focuses on teaching pedagogies at the secondary and college levels.