By Aileen Cudmore and Darina M. Slattery

Abstract

Purpose: This article examines physical and rhetorical characteristics of videos used to promote technology projects on Kickstarter. In this study, successful projects are defined as projects that reached their funding goal; failed projects did not meet their funding goal.

Method: Content analysis of 25 successful and 25 failed technology project videos. Cross-cultural analysis of successful U.S. videos and non-U.S. videos.

Results:

- Successful project videos were more likely to include iconic and analytic still images and to demonstrate the final product; usually displayed a combination of static and dynamic pictures; and tended to use shorter on-screen texts.

- All videos comprised at least one of the kairos subtypes.

- Successful U.S. videos were more likely to present the creator onscreen, include static pictures and provide information on why the creator needed donations (logos). These also always referred to timeliness or a call to action (kairos).

- Successful non-U.S. videos were much more likely to refer to the exclusivity of the product (pathos)

Conclusion: Kickstarter project videos are an important feature on the main project page and may influence potential supporters’ decisions to fund projects. While other factors can also contribute to project success, an awareness of physical characteristics and rhetorical appeals of successful videos can help project campaigners, technical communication practitioners, and educators create more effective videos.

Keywords: crowdfunding, technology project videos, content analysis, rhetorical analysis, physical characteristics of videos

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Videos for technology projects on Kickstarter varied considerably in their physical characteristics and in their use of rhetorical (particularly, ethos and pathos) appeals.

- The videos for successful (funded) projects differed from those for failed projects, but there were also some similarities.

- Crowdfunding entrepreneurs and video developers can learn how to construct more appealing videos, particularly for technology projects.

- Technical communication practitioners can learn how to develop more engaging and persuasive videos.

- Educators can learn how to develop better instructional videos.

Introduction To Crowdfunding

Entrepreneurial finance, which is funding that is made available to entrepreneurs, has evolved considerably in the last decade. Traditional methods of finance for emerging businesses include investments from friends and family, lending from banks, and venture capitalists (investors who provide funds to small businesses). Shark Tank, a reality television series based on Dragon’s Den, offers opportunities to aspiring entrepreneurs to make business presentations to a panel of potential investors. In more recent years, Web-based crowdfunding has emerged as another possible alternative to traditional models (Cordova et al., 2015; Mollick, 2014).

Crowdfunding rapidly developed after the 2008 financial crisis in response to the increased difficulties faced by early-stage entrepreneurs attempting to raise funds. One such response was President Obama’s JOBS Act of 2012, which included a reference to crowdfunding (Cordova et al., 2015). The crowdfunding finance model enables entrepreneurs to acquire investments from the public over the Internet to help develop new projects. In return, supporters (also known as backers) can gain a reward (e.g. meet the artist behind a project or receive sample products), a return on their investment, or a percentage stake in the company. Crowdfunding platforms (such as Kickstarter, IndieGoGo, and RocketHub) facilitate the exchange between project creators and supporters by providing webpages where creators can pitch their project ideas. Proposal types vary considerably—for example, they may be for music tours, book publishing, tabletop games, one-time events (e.g. parties), and even medical expenses (Cordova et al., 2015; Kickstarter, 2018).

Between 2009 and 2018, Kickstarter, a market leader in reward-based crowdfunding, received approximately $3.5 billion in pledges from over $14 million backers for over 138,270 projects (Kickstarter, 2018). While some projects only aim to raise a few dollars, and most successful projects raise less than $10,000, a number of project creators have had enormous success with the crowdfunding model, raising millions of dollars through large quantities of small donations (Kickstarter, 2018). High profile success stories, such as Oculus (virtual reality devices) and Pebble (smartwatches), have increased the popularity of crowdfunding (Mollick, 2016). Table 1 presents details of the most funded projects on Kickstarter.

Table 1. The most funded projects on Kickstarter

| Project | Amount Raised (USD) | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Pebble Time | $20,338,986 | Design |

| Coolest Cooler | $13,285,226 | Design |

| Pebble 2 | $12,779,843 | Design |

| Kingdom Death: Monster 1.5 | $12,393,139 | Tabletop Games |

| Pebble: E-Paper Watch | $10,266,845 | Design |

Success in a crowdfunded project is often determined by whether the project reached its funding goal or not. If a project falls short of its funding goal, which may be small or large, none of the backers has to pay his or her pledge. In Kickstarter’s (2018) statistics for different project categories, projects related to dance, comics, and music have the highest success rate; however, this rate is calculated by dividing the number of successfully funded projects by the number of all projects that have reached their deadline (including successful, unsuccessful, canceled, and suspended projects). While projects can fail for any number of reasons—including a poor-quality product, a poor ‘pitch’, and poor timing (kairos)—much of the previous research has focused on identifying the factors that contribute to a project’s success (Cardon et al., 2009; Gerber & Gui, 2013; Hobbs et al., 2016; Mollick, 2014). One factor that can influence this success is the project or campaign video (Mollick, 2014), which appears at the top of a project page. Creators use these videos to pitch their proposed projects and to highlight the benefits of investing. Consequently, project campaigners should be interested in knowing which physical and rhetorical characteristics make an effective Kickstarter campaign video. These characteristics are also of interest to mass communication and technical communication practitioners who develop videos and to educators who develop instructional videos for students.

Characteristics of Crowdfunding Project Campaign Videos

A crowdfunding campaign video is simply a visual pitch of the campaign that informs viewers (potential project backers) about the crowdfunding project. However, due to the online setting of crowdfunding, a video can be one of the most effective ways to convey information about a project. Videos can potentially engage supporters in a more dynamic way than just a textual project description, as they can enable creators to appeal directly to their audience, express their passion, and emphasize why the project must be fulfilled (Steinberg & DeMaria, 2012).

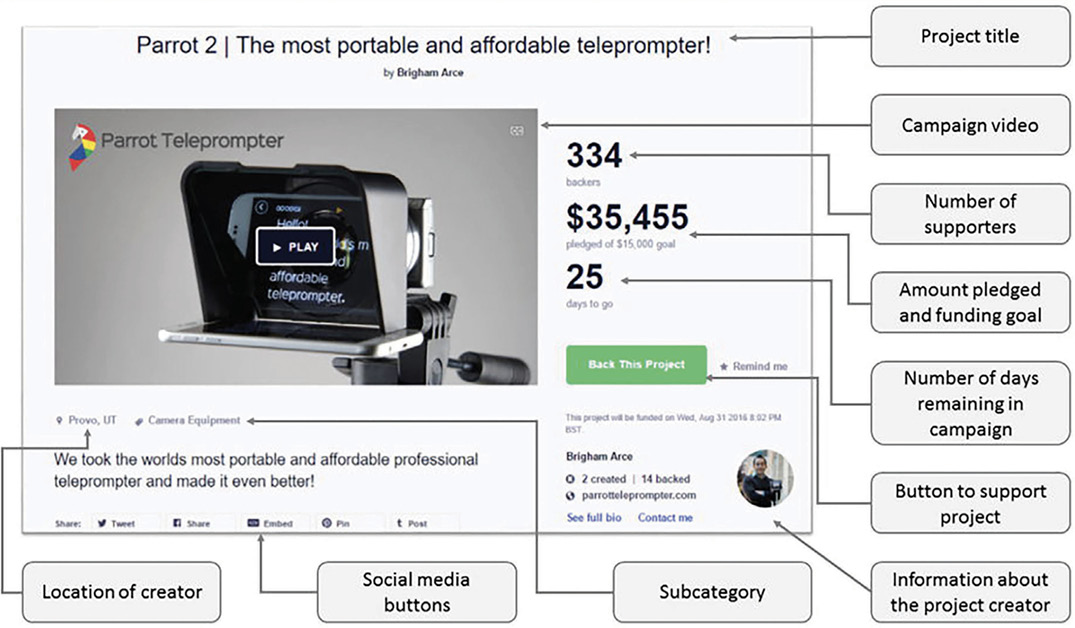

On Kickstarter, videos have a prominent position at the top of every project campaign page (see Figure 1). Kickstarter outlines some very general tips for making a video (Benovic, 2016; O’Connell & Kurtz, 2012) and provides a dedicated discussion forum where project creators can find advice from their peers (Kickstarter, 2017a).

Several studies suggest that the use of video is an important variable affecting crowdfunding success. Frydrych, Bock, Kinder, and Koeck (2014) found that 87% of Kickstarter projects incorporated a video on the campaign page. Marelli and Ordanini (2016) found that crowdfunding campaigns with a video had a higher probability of achieving successful funding. Similarly, another study found that those projects with a video tended to perform better than those without (Lindroos, 2016).

However, simply having a video is not necessarily an indicator of success. One study suggested that the presence of a video has become standard, with the majority of successful and failed projects in that research containing a video (Frydrych et al., 2014). Similar results were found by Carlsen and Høgh (2016), with 98% of successful and 81% of failed campaigns providing a video. Furthermore, a crowdfunding campaign can still be highly successful without a video (Young, 2013). Nevertheless, it is likely that the content of successful and failed videos differ, and that these differences may influence potential backers’ decisions to fund projects.

Although the characteristics of online videos have been studied previously (see, e.g., Dowhal et al., 1993; ten Hove & van de Meij, 2015), little is known about the factors that make crowdfunding campaign videos engaging. Many recommendations are based on personal observations and experiences, rather than solid academic research (Steinberg & DeMaria, 2012). One study suggested that persuasiveness, humor, and multimedia can affect people’s opinion toward online videos (Hsieh, Hsieh, & Tang, 2012). Recent findings from Kaminski, Jiang, Piller, and Hopp (2017) suggested the Kickstarter video pitches from ‘lead user’ entrepreneurs—entrepreneurs who “sense needs long before they become known to the broader public” (p. 2683)—are more orientated toward the product and problem solving. Hobbs, Grigore, and Molesworth (2016) suggested successful videos show evidence of passion (e.g. showing visual cues in the pitch video or evidence of time invested) and preparedness (e.g. displaying a level of detail within pitch documents).

As the creators often decide on the content of the video, it is likely that the features of the video will vary from project to project (Reyes & Bahm, 2016). However, it is possible to evaluate certain aspects of the physical design of video, such as the timing and production quality. Similarly, the persuasive nature of the video can be assessed by examining the type of rhetorical appeals used in the accompanying narration. We will discuss some literature relating to physical characteristics and rhetorical appeals in the next section. It is worth noting that even if a video generates positive feedback from viewers, this feedback is not necessarily enough to guarantee that a project will be successful. For example, in a focus group study about one successful and one unsuccessful music project, the interviewees did not consider either project worthy of support, based on the video alone, even though the interviewees identified many positive features in the videos (Byg-Fabritius & Willumsen, 2013). In that study, the interviewees cited other reasons why they would not back either project, which included the way the music artist attempted to secure funds (they did not like being “guilt-tripped” into supporting the cause) and they argued that they (the music artists) were famous enough to secure funding elsewhere.

Physical Characteristics

Online videos—which might be viewed on desktops, tablet PCs, or smart devices—have many features that may determine their overall quality. Several recent studies have investigated the characteristics of online videos. ten Hove and van der Meij (2015) identified physical characteristics that distinguished popular instructional videos on YouTube from unpopular ones; these characteristics related to resolution, visuals, verbal and sound, and tempo. Other research developed best practice advice for creating online instructional videos, highlighting the importance of video and audio production quality. For example, Swarts (2012) found the use of quality voice-overs and planned, scripted, and edited videos contributed to the overall production quality; likewise, the use of professional screencasting software can also improve the quality. Swarts also identified specific features of “good” videos, which included significant time introducing the instructional agenda and the demonstration and explanation of steps. Good instructional videos are also easy to locate, understand, and use, and they are engaging and reassuring (ibid).

Some studies have examined the benefits of using instructional animations, videos, and static pictures (see, e.g., Arguel & Jamet, 2009; Höffler & Leutner, 2007). Ploetzner and Lowe (2012) distinguished five significant characteristics in the physical design of animated videos used for instructional purposes. They confined their study to animations that are computer-based, have an expository purpose, are artificially created using drawings or models, imitate processes to be learned, and are pre-authored to help learners understand an entity, structure, or process.

Having reviewed several studies, the following physical characteristics appear to be the most important for online videos:

- Resolution: The spatial resolution refers to the number of pixels displayed on a screen object and is normally written as ‘width x height.’ Screens with a large number of pixels are important for showing sharp images and distinguishing details. Related to resolution is the display aspect ratio, which is the proportional relationship between the width and height of a screen object. Swarts (2012) recommended High Definition (HD) or near-HD. In a recent study, the most popular YouTube instructional videos were produced in High Definition (HD) quality (ten Hove & van der Meij, 2015).

- Visuals: Visuals refer to all the pictorial information in the video, such as whether still (static) or moving (dynamic) images are used (Ploetzner & Lowe, 2012; ten Hove & van der Meij, 2015). Static images can “emphasize detail by holding it in place” (Swarts, 2012, p. 203). Arguel and Jamet (2009) found that the best learning scores were found when video was used with static pictures. Another distinction is between real (or realistic) and abstract (or illustrated) visuals (ten Hove & van der Meij, 2015). ten Hove and van der Meij found that analytic static pictures (illustrations that symbolize objects or states rather than real objects) appeared more often in popular YouTube videos but there were no significant differences in types of dynamic images, whether they were real-time images (e.g., video) or animations.

- Audio: Audio refers to the presence of music, spoken words, or any other sounds in the video. Spoken words may include speech from an onscreen presenter and narration from a presenter off-screen. Audio can be used to signal a change in topic and to give the eyes a rest (Swarts, 2012). Narration is found more in popular YouTube videos than in unpopular videos (ten Hove & van der Meij, 2015).

- Onscreen texts: Onscreen texts represent any written words that appear onscreen, with the exception of the title (ten Hove & van der Meij, 2015). Some campaign videos have no spoken words and, instead, convey all their information through written texts onscreen. The onscreen texts category also includes the presence of subtitles. Text can be used to clarify video and to organize the video (Swarts, 2012). ten Hove and van der Meij found that popular instructional videos on YouTube comprised onscreen text more than unpopular ones. They also recommended the use of video transcripts.

- Tempo: Tempo describes the pace of the video, including the length, frame rate, and narrative speed. Previous studies suggested that the length of campaign videos should be no longer than three minutes (Drabløs, 2015), but no study has yet shown if campaign creators actually adhere to this guideline. Narrative speed is also important—the narration should be normal and consistent in its pacing, and synchronized to the visual action in the video (Swarts, 2012). The ten Hove and van der Meij (2015) study found the most popular instructional videos on YouTube had an average narrative speed of 172 words per minute (wpm), which is a good deal faster than the average U.S. speaker rate of 150wpm (National Center for Voice and Speech, n.d.).

- Branding: Branding includes the presence of the product or company logo on the screen. It is an important persuasive tool, as prominent placements are likely to improve viewers’ memories of the product (Cowley & Barron, 2008). Footage of the proposed project or final product helps to build confidence in the creator’s abilities (Cardon, Wincent, Singh, & Drnovsek, 2009).

Rhetorical Appeals

The ultimate intent of a crowdfunding campaign video is to promote the creator’s project and to persuade potential supporters to fund the project. Decades of research show a message’s ability to persuade is determined by the characteristics of the communicator, the message, and the audience (Lasswell, 1948).

Previous studies have examined audience characteristics in the context of reward-based crowdfunding, in which the audience (potential funders) is motivated to support the creators by the promise of some kind of reward (Mollick, 2014). For the most part, the audience members are not professional investors and often include individuals who have a personal link (family or friend) to the project creator (Agrawal et al., 2010). Alternatively, the funders may be treated as early customers, and, by supporting the project, they gain access to the product at an earlier date, at a better price, or with some other special benefit. However, the individual motivations of funders are often complex and highly variable. In a series of interviews with supporters, Gerber and Hui (2013) found funders were motivated by a desire to gain rewards, help others, support causes, and be part of a community. Nonetheless, studies have shown most funders respond to signals about the quality of the project, regardless of other factors (Courtney et al., 2017; Koch & Siering, 2015; Marelli & Ordanini, 2016). Because it is difficult for crowdfunding project creators to control audience characteristics (e.g., their demographics, preferences, and beliefs), our study focuses on the communicator and message factors of videos, rather than the audience.

According to Aristotle’s means of persuasion, the communicator’s characteristics comprise ethos appeals, while the message characteristics include logos and pathos appeals (Meyer, 2012). These three rhetorical appeals are some of the most effective ways of investigating the persuasive nature of communication (Tirdatov, 2014):

- Ethos refers to the credibility of the communicator. In terms of campaign videos, the creator’s characteristics and trustworthiness should influence the degree to which the viewers find the campaign credible and persuasive (Hovland & Weiss, 1951). Online, creators can convey their ethos by demonstrating their competence and professional affiliations (Tirdatov, 2014). These strategies may improve the attitudes of potential supporters toward the crowdfunding project (English, Sweetser, & Ancu, 2011).

- Pathos refers to the use of emotional appeals, which can influence the attractiveness of online videos by evoking a positive or negative emotional response in the viewer (Hsieh et al., 2012). In particular, positive feelings, such as joy and humor, may help to increase the popularity of a video (Elliott, 2013).

- Using a logical approach, or logos, a project creator provides factual information to support the claims he or she makes in the campaign video and to prove that the project is worth funding. For example, the project creator might give a list of specifications for a new device or product. The logical approach enables potential backers to evaluate the project based on that information.

Due to the novelty of the online crowdfunding concept, prior research related to the rhetoric of campaign videos is scarce. Nonetheless, the related field of traditional fundraising often uses rhetorical appeals to secure donations (Ritzenhein, 1998). Appeals are also effective online and can greatly improve the rate of recruitment in digital surveys (Rife, 2010). Furthermore, studies have recommended rhetorical appeals play a central role in marketing and advertising (Marsh, 2007; Tonks, 2002).

Most previous research on the rhetoric of online videos has investigated political campaigns and promotions. One study found YouTube videos in favor of a new piece of legislation used mainly pathos appeals (e.g., emotion), while those against incorporated more logos appeals (e.g., factual information) (Krause, Meyers, Irlbeck, & Chambers, 2015). In a study of political user-generated videos from Singapore, the most popular videos usually relied on strong emotional appeals (Lin, 2015). An analysis of campaign videos for non-governmental organizations found they typically use either persuasive rhetoric, with the presenter speaking in the first person about non-specific, complex information, or logos appeals, with the presenter speaking in the third person about specific, simple information (Almaraz, González, & Van-Wyck, 2013).

One recent study used Aristotle’s concepts of ethos, pathos, and logos to develop a framework to classify the rhetorical means of persuasion used in the textual descriptions of Kickstarter projects (Tirdatov, 2014). Tirdatov found the most-funded projects contained all three types of rhetorical appeals, and these appeals could be subdivided into specific subtypes.

Another rhetorical appeal that is likely to be relevant is kairos, or timeliness. In terms of crowdfunding campaigns, kairos might refer to a call to action or timely opportunity to support a project (e.g., “Avail of this one-off opportunity to invest in . . .”) or an opportunity to avail of a timely solution to a particular need (e.g., “This is the only product in the market right now that can . . .”). Kairos might also refer to the inclusion of a deadline or goals. In her study of the successful administration of online surveys, Rife (2010) proposed kairos might even surpass ethos, pathos, and logos as a rhetorical strategy “because no matter how perfect the ethos, no matter how strong the pathos, and no matter how logical the argument, if the timing is wrong, the audience will not listen” (p. 262).

Our study uses the ethos, pathos, and logos appeals and subtypes identified by Tirdatov (2014), as well as two kairos subtypes, as a basis to investigate the rhetorical appeals in Kickstarter campaign videos. We will discuss these appeals and subtypes in the results and discussion section.

Methodology

In our study, the goal was to analyze the characteristics of campaign videos for technology projects on Kickstarter, a popular online crowdfunding platform (Young, 2013). The aspects of campaign videos we investigated relate to the physical characteristics of the video and rhetorical appeals used in the accompanying spoken narration. In this study, we define a successful campaign video as one that reached its funding goal and a failed campaign video as one that did not reach its funding goal. If a project falls short of its funding goal, none of the backers has to pay his or her pledge.

Research Questions

We conducted a content analysis on the campaign videos from Kickstarter technology projects, with a view to answering the following research questions:

- To what extent do successful Kickstarter campaign videos for technology projects differ from failed videos in their physical characteristics?

- To what extent do successful Kickstarter campaign videos for technology projects differ from failed videos in the rhetorical appeals that they use in their spoken narration?

- To what extent do successful U.S. videos differ from successful non-U.S. videos in their physical characteristics?

- To what extent do successful U.S. videos differ from successful non-U.S. videos in the rhetorical appeals that they use in their spoken narration?

Our Approach

In our study, we adopted an empirical research approach, which uses the scientific method (Hughes & Hayhoe, 2008). The advantage of empirical research is that it is relatively objective, as it uses quantifiable observations to form the results. However, the focus of the research is narrow, and any findings are constrained by the original research question(s).

We used a content analysis to evaluate the campaign videos. Although content analysis is traditionally associated with written documents, it also includes non-written documents such as video (MacNealy, 1999). The traditional approach to content analysis is quantitative and involves measuring the number and type of categories present in a document (Neuendorf, 2002).

We also used qualitative content analysis to select illustrative examples from the videos to explore the main findings. Such qualitative analysis helps to support quantitative studies, which, on their own, might be misleading (Nielsen, 2004).

Video sampling

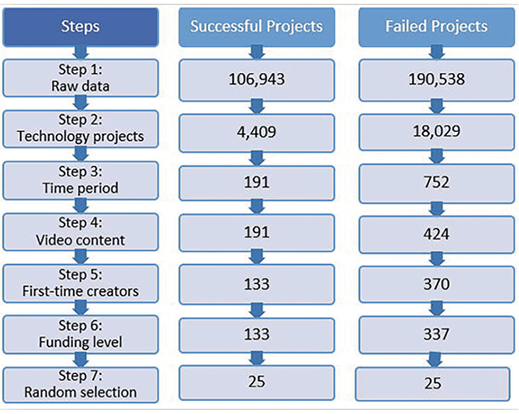

We evaluated campaign videos filed under the technology category on Kickstarter. The technology category includes a diverse set of products and services, including apps, 3D printing equipment, robotic devices, and software. We selected the videos for this research through a series of seven steps, which reduced the original pool of videos to a final sample of 50 (see Figure 2).

These steps were:

- Step 1: Raw data. The raw dataset contained the 106,943 successful and 190,538 failed campaigns that launched on Kickstarter from April 2009 to June 2016.

- Step 2: Technology projects. We excluded all campaigns that were not in the technology category from the dataset. As of June 6, 2016, Kickstarter had launched 4,409 successful and 18,029 failed projects in the technology category.

- Step 3: Time period. We limited the selection of videos to campaigns that ran from January 1, 2016 to March 31, 2016. Given that these were technology projects, selecting (then) recent projects ensured that any findings were as current to the literature as possible. Step 3 provided a sample of 191 successful and 752 failed projects.

- Step 4: Video content. Of the failed projects, 328 did not include any type of campaign video. We excluded these projects from the dataset, leaving 424 failed projects in the sample. Every successful campaign comprised a video, so there was no further filtering in this step.

- Step 5: First-time creators. We only included projects produced by first-time creators in the dataset. Creators who had previously created a successful project can build upon a pre-existing audience (Mollick, 2014). Prior success gives creators a considerable advantage over first-time creators and may act as a confounding factor in the analysis. Step 5 reduced the number of successful projects to 133 and failed projects to 370.

- Step 6: Funding level. For the failed projects, we also excluded those that received no donations. Step 6 ensured that only those with potential backers were included in the study and reduced the number of failed projects in the database to 337.

- Step 7: Random selection of videos for detailed analysis. We used a random sampling method to select the final 25 successful projects and 25 failed projects to examine in detail. We chose 50 projects, as it represents just over 10% of the pool remaining (i.e., 133 successful and 337 failed projects). First, we ranked all projects in order of the percentage-funding goal reached. Then, we selected 25 projects from each of the successful and failed ranks using the random integer set generator from RANDOM.ORG (Randomness and Integrity Services Ltd., 2016). Step 7 provided us with 50 videos (25 successful and 25 failed) for further analysis (see Appendix A). We downloaded these videos and saved them as mp4 files.

Codebooks

We then developed codebooks, which describe how we coded (tagged) and scored a video based on its external properties, physical characteristics, and rhetorical appeals. We developed the codebooks to ensure consistency and to enable other researchers to replicate our study. The codebooks are available in Appendices B through D. Prior to the collection of the research data, we conducted pilot coding to test the codebooks. As a result, we made several revisions, which helped to improve the reliability of the coding scheme (Neuendorf, 2002):

- External properties: These properties included descriptive data, which are important for locating and identifying a video. Kickstarter presents this data on the campaign page of every project. We gave each video a unique ID code, numbered from 101–150 (see Appendix B). The descriptive data included the URL, title, and currency. In addition, we included statistical data about the project, such as the campaign start and duration, funding goal, final amount raised, and total number of backers.

- Physical characteristics: We developed a codebook for physical characteristics based on the framework used by ten Hove and van der Meij (2015). The codebook included 27 items divided into six main categories: resolution, visuals, audio, onscreen texts, branding, and tempo (see Appendix C). We assigned these items to one of two mutually exclusive classes: absent (0) and present (1), and recorded continuous data as their actual values. These included the frame rate, video length, and narrative speed, which we estimated by counting the average number of words spoken per minute by the narrator.

- Rhetorical appeals: We also assessed the videos for the rhetorical appeals they use in the accompanying narration. We developed a framework for assessing verbal rhetorical appeals based on findings from Tirdatov (2014). The Tirdatov framework consisted of 11 subtypes divided into three main types of appeal: ethos, pathos, and logos. We also identified two kairos appeals that are relevant to crowdfunding videos. The codebook provides a detailed description and illustration for coding and scoring each of these subtypes (see Appendix D).

In order to code the rhetorical subtypes, we first transcribed the narration that accompanied each video and saved the script as a .txt file. Then, we coded the text using categories that denoted the 13 subtypes of rhetorical appeals. We carried out all coding in Weft QDA (Fenton, 2014). Next, we recorded the presence (1) or absence (0) for each of these subtypes in each video. If a single sentence contained more than one rhetorical appeal, we counted it as one example of each of the individual subtypes identified within that sentence.

Data Analysis

We recorded all information relating to external properties, physical characteristics, and rhetorical techniques in separate Excel files. Because five successful (20%) and seven failed (28%) videos did not contain any spoken narration, we did not code these twelve videos for rhetorical appeals and excluded these videos from the final rhetorical analysis.

We expressed the results of the nominal data as percentage frequencies of the total number of videos analyzed. For continuous data, we calculated the average result of successful and failed videos, or the median value if the variables were non-normal.

We analyzed the data by comparing successful and failed results for each of the variables. Most of the data were nominal variables, with each item classified as being either present or absent from a video. These data were analyzed using 2-way Chi-squared (χ²) tests. If the data did not meet the conditions of the Chi-squared test because of low expected frequencies, we analyzed them using the Fisher Exact Probability test. We analyzed the continuous variables using an unpaired t-test (for normal data), or Mann-Whitney U-test (for non-normal data). We completed all analyses in Microsoft Excel.

Results and Discussion

Here, we present the findings of the external properties of the sampled videos, an overview of the physical characteristics, followed by an overview of the rhetorical appeals of the language used in the videos. In a brief case study, we also outline the characteristics and appeals used in one successful and one failed video. Finally, we present the findings from a cross-cultural analysis of physical characteristics and rhetorical appeals in the successful U.S. and successful non-U.S. videos.

Description of the Sampled Videos

As outlined earlier, we examined 25 successful and 25 failed campaign videos for technology projects on Kickstarter. All campaigns were from first-time creators and ran from January to March 2016.

These projects sought funds for a diverse set of technology offerings, including apps, 3D printing equipment, robotic devices, and software. The projects raised funds in eight different currencies, the most popular of which were the U.S. Dollar (38%), Euro (22%), and British Pound (20%). None of the currencies was significantly associated with either successful or failed campaigns.

As expected, successful projects raised significantly more funds than failed ones (t=1.68; P<0.001). The most successful project in this study, ChameleonMini, raised €190,519 (approximately $215,000 USD). Similarly, successful projects reached a significantly higher percentage of their original funding goal (Mann-Whitney U-test, U=0; n1=25, n2=25; P<0.01) and received funds from significantly more people than failed projects did (Mann-Whitney U-test, U=18; n1=25, n2=25; P<0.01). The most popular project gained the support of 1,778 people, whereas only one person supported the least popular project.

Some studies suggest that campaigns fail because they choose unreasonable funding targets (Frydrych et al., 2014). The funding goal of successful and failed projects in this study ranged from as little as $1,473 USD to as much as $346,670 USD, with a standard deviation of ± $7,352.60 USD. The average funding goal ($30,258 USD) is comparable with the levels of funding from financial institutions (Mollick, 2014) and suggests most project creators are serious about raising money.

Similarly, previous studies have suggested failed campaigns set overly long campaigns, which can hinder their overall success (Marelli & Ordanini, 2016). However, most projects in this study set campaign durations of around 30 days, which is similar to the project length suggested by Kickstarter (Strickler, 2011). These results indicate first-time creators incorporate basic advice on crowdfunding that is available to them.

Physical Characteristics

Appendix C presents the codebook used to record the physical characteristics (resolution, visuals, audio, onscreen texts, branding, and tempo) of Kickstarter videos. Our analysis of these physical characteristics reveals most videos, both successful and failed, incorporated some similar characteristics, including relatively good production quality, relatively clear audio (narration, music, sound, and noise), and a 16:9 screen aspect ratio. Other commonly used features included realistic dynamic pictures and branding logos. The majority of successful and failed videos also adhered to Kickstarter’s recommended video length (no longer than three to five minutes) and lasted, on average, 2 minutes and 30 seconds. However, as several characteristics were significantly associated only with successful videos, it is possible that these subtler aspects were responsible for engaging viewers and compelling them to action (Morain & Swarts, 2012). The next section will discuss those distinct characteristics. Later in this article, we will analyze characteristics of one successful and one failed video, with the aid of screenshots.

Distinct successful characteristics

One of the main distinguishing factors of successful videos is in their use of a combination of visual materials (e.g., colored and black and white images, dynamic and static images, and animations), but, particularly, the inclusion of static images. In many of the successful videos, static or still images were used to focus on the details of the product. Such images can be a powerful tool for processing information (Arguel & Jamet, 2009; Smith & Ragan, 1999). Using a combination of visuals helps to keep viewers engaged and motivated (Alexander, 2013). While many project campaigners recognized the importance of using a logo to express a visual identity—logos appeared in 19 successful (76%) and 15 failed videos (60%)—a logo alone does not appear to be enough to persuade viewers to support a campaign. Unlike failed videos, which tended to show prototypes (n=17, 68%) more often than the final product (n=10, 40%), the majority of successful videos (n=19, 76%) demonstrated the final product onscreen. Such actions help to make the project more memorable for viewers (Cowley & Barron, 2008) and demonstrate tangible proof that the creator will be able to complete the project.

On a related note, Fernandes (2013) found when visually stimulating videos are used, the creator appears to be more capable and the success rate of the project is likely to be higher. Nielsen (2005) found many viewers are bored by videos that only show the presenter speaking straight to the camera—interestingly, this kind of presentation was a feature of several failed videos. Finally, many successful videos clearly linked the visuals with the narration, which helped to make the video more understandable (Plaisant & Shneiderman, 2005).

The majority of successful videos included some onscreen text, usually in the form of short texts. These short texts usually took the form of labels, titles, or short phrases that introduced the creator (e.g., “I’m Craig Leaf, founder of Appostasy”). The use of short texts in combination with the narrative and visuals helps to identify technical features and to create a memorable image (Clark & Mayer, 2008; Ploetzner & Lowe, 2012). In contrast, long texts were more likely to occur in failed videos. These texts generally came in the form of slides or written messages, and usually carried the main message of the video. However, most research advises creators to reduce onscreen text, as it takes longer for viewers to process (Clark & Mayer, 2008). Thus, videos with lengthy text are more likely to be unappealing and less persuasive to viewers.

In terms of audio, there was a trend for successful videos to have the creator of the campaign present some information onscreen. Many previous studies show such personalization is important for videos (Guo et al., 2014; van der Meij & van der Meij, 2013). Furthermore, narration can often enhance visuals (Atlas, Cornett, Lane, & Napier, 1997) and enables the viewer to retain more information than he or she would retain from either medium on its own (Rieber, 2000). In the 20 successful videos that contained narration, the narration speed ranged from 93wpm to 166wpm. In the 18 failed videos that contained narration, the speed ranged from 94wpm to 203wpm. While the average speed for successful videos (140wpm) was slower than the average speed for failed videos (144wpm), both average narrative speeds were still lower than the average U.S. speaker rate of 150wpm (National Center for Voice and Speech, n.d.) and the most popular YouTube instructional videos analyzed in the ten Hove and van der Meij (2015) study (172wpm), suggesting that crowdfunding video narration may be slower than average.

Our findings suggest successful project creators may take more time and effort when developing their videos, as there are some specific characteristics that are associated more with successful videos. Potential backers may view the quality of these videos as a signal of quality for the whole campaign (Chen, Yao, & Kotha, 2009; Mollick, 2014).

Rhetorical Appeals

We also analyzed the rhetorical appeals used in spoken narration in successful (n=20) and failed (n=18) campaign videos, focusing on common appeals, distinct successful appeals, and rare appeals. Appendix D presents the codebook used to record the rhetorical appeals (ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos) and defines the 13 subtypes. There was a significant difference in the average number of subtype appeals per video, with successful videos (9 ± 1.4) using significantly more subtype appeals in narration (Mann-Whitney U-test, U=44; n1=20, n2=18; p<0.05) than failed videos (6 ± 1.6).

Our analysis of Tirdatov’s (2014) rhetorical characteristics reveals that the appeal subtypes common to most successful and failed videos are L5, L1, and P2 (see Appendix D). Of the videos comprising spoken narration, 90% of successful (n=18) and 94% (n=17) of failed videos began with some form of L5 appeal subtype. An L5 subtype provides general data and background information about the project. Many videos used this technique to describe the problem that the crowdfunding project will solve. After the L5 appeal, there was usually some kind of outline of the actual features and characteristics of the product (L1 subtype), which occurred in 95% of successful (n=19) and 94% of failed videos (n=17). Finally, in 100% of successful (n=20) and 83% of failed videos (n=15), there was some reference to the positive, emotionally rewarding implications of supporting the project (P2 subtype). By claiming to solve certain problems, the videos implied the projects would, ultimately, have a positive impact on supporters’ lives. Together, these three basic appeal subtypes reflect the qualities that make solid written proposals: a definition of a problem or opportunity and a detailed plan to respond to the problem (Markel, 2012).

In terms of kairos appeals, contextual information on why the project fulfills a need for the current situation (K1 subtype) occurred in 80% of successful videos (n=16) with spoken narration but only in 56% of failed videos (n=10). However, references to timeliness or a call to action to support the project (K2 subtype) occurred in 85% of successful (n=17) and in 89% of failed videos with spoken narration (n=16). The frequency of the K2 subtype appeal is not surprising, however, given that Kickstarter campaigns tend to feature new and innovative projects, and campaigners need to create a sense of urgency if they are to meet their funding goals by the deadline.

Distinct successful appeals

Appeal subtypes that distinguished successful videos from failed ones were E1, P1, P3, and often L2 (see Appendix D). The E1 subtype, which makes an implicit claim about the credibility of project owners by demonstrating professionalism and expertise, occurred more frequently in successful videos, which suggests ethos plays an important role in reassuring potential supporters that the project will be successful. Previous research also suggests such confidence-building claims are a feature of good online videos, while poor videos seldom contain such claims (Morain & Swarts, 2012). Another study confirms this finding by indicating that ethos is the most important appeal in YouTube political videos (English et al., 2011).

Since 95% of successful videos with spoken narration (n=19) included two or more pathos subtypes, compared with 56% of failed videos (n=10), this finding points to the usefulness of incorporating emotional narrative techniques in campaign videos. However, these subtypes do not specify the type of emotion that should be used. Advice from online forums suggests that creators should use humor in their videos (Kickstarter, 2017b). However, in the videos we analyzed, the pathos evidence frequently related to enthusiasm for the project, through the use of words such as “awesome” and “passionate” (P1 subtype). Most videos possibly avoided humor, because it can lower the credibility of the project if not used well (English et al., 2011). P3 subtype claims relating to exclusivity are also important as they can generate a positive emotional perception of the project. Research shows that people generally attach more value to products that are rare, distinct, or available for a limited time (Mitra & Gilbert, 2014).

Finally, L2 subtypes, which provide information on the benefits and rewards that the project offers to supporters, were also associated with successful projects. The L2 subtype has a similar aim to the P2 subtype (the positive, emotionally rewarding implications), but lacks the emotional language of the P2 subtype. In cases where the L2 subtype was missing, the objective was possibly met by the P2 subtype.

Rare appeals

Several appeal subtypes were rare in both successful and failed videos, including E2, E3, L3, and L4. In terms of the E2 subtype, the videos rarely referred to the involvement of a famous person, organization, or product in the project. Such appeals may be more likely to occur in creative projects, such as those for music, dance, or film, where the project owner may be a famous screenwriter, musician, or established author (Tirdatov, 2014).

In terms of E3 appeals; which are concerned with references to third-party recommendations, reviews, or testimonials; if creators had third-party reviews, they tended to include them in the textual description on the project page, rather than in the videos, as they could include a list of the sources with hyperlinks to full reviews on external websites. Sometimes, further down the campaign page, the creators included additional YouTube videos of reviews and testimonials from third parties.

Similarly, L3 subtypes (information on financial terms) did not appear to be an important subtype for these campaign videos. The basic funding mechanism operates very much the same way on all Kickstarter projects (i.e., projects that fail to reach the funding goal are cancelled and people who pledge to back the project are not charged), which is probably why most video creators choose not to spend time repeating those terms. Rather, this information is probably best suited to a textual description elsewhere on the campaign page.

The L4 subtype, which provides information on why exactly the creators need donations and how creators will use donations, was rarely used. It is possible that there was insufficient time to elaborate on this information in the videos and/or it was better suited to a textual description on the campaign page.

A Case Study of a Successful and Failed Video

In this section, we will discuss physical and rhetorical characteristics of one successful video and one failed video.

A successful video

There are a number of campaign videos that correspond strikingly well with the average characteristics of a successful video. One of these is for a project called “PenSe: Apple Pencil Case. Make the world your canvas” (Project 115, see Appendix A). The PenSe campaign was created by a company called Appostasy Inc. and ran from January 27 to February 26, 2016 (30 days). Six hundred and sixty-one backers pledged $38,076 of the $32,000 goal to fund the project.

The video for this project has a high production quality and uses a 16:9 aspect ratio. It has a frame rate of 30 frames per second and is composed of a combination of dynamic and static pictures. In addition, the audio is free of extraneous noise and the video is free of blurred visuals. The total length of the video is 3 minutes and 6 seconds.

The video begins with an off-screen narrator describing a problem (L5 subtype) with a new pen for Apple iPads, which is shown in a series of static pictures while gentle music plays in the background (see Figure 3a). The introduction arouses curiosity in viewers with an interest in Apple products. The narrator illustrates the solution to the problem by describing the product that the company has developed (L1 subtype), while the final product is displayed onscreen (see Figure 3b). The narrator uses words with an emotional narrative (‘safe’, ‘simple’, and ‘elegant’) (P1 subtype) and highlights the exclusivity of the product (‘the first pencase’) (P3 subtype).

The narrator then introduces himself onscreen (E1 subtype), providing a personal link to the creative team (see Figure 3c). At the same time, onscreen text displays his name and position at the company (‘Craig Leaf, founder of Appostasy’), as well as the company logo. The creator also uses this introduction as an opportunity to reference his previous experience in creating similar products (E1 subtype). The video concludes with the presenter making an appeal for funding (‘to begin production, we need your help’) (see Figure 3d). He references the positive implications (L2 subtype) of supporting the project (‘a superior product,’ ‘affordable price,’ and ‘right here in Massachusetts’), and the screen shows a final large shot of the product logo.

A failed video

Since 32% of failed videos were for an app (compared with just 8% of successful videos), we will use one of these videos as an example of a failed video. The campaign “TetherMe App” was created by AstroApps.com and ran from January 25 to February 15, 2016 (20 days) (Project 140, see Appendix A). Six backers raised $61 (NZD) for the project, out of a goal of $4,500 (NZD).

The video does not follow the structure of the successful PenSe video shown in Figures 3a–3d. Firstly, the length of the video is shorter than average at 49 seconds long (versus 3 minutes and 6 seconds for the successful PenSe video). In terms of rhetorical appeals, it reveals no information about the creators behind the project (unlike the successful video), which in turn makes it appear more like an advertisement than a project campaign video. The information is presented entirely by an off-screen narrator who does not appear to be the creator of the project, and the viewer never sees the creator onscreen. The narrator speaks relatively quickly, at 165 words per minute (wpm); according to the National Center for Voice and Speech (n.d.), the average rate of speech for English speakers in the US is about 150wpm. Although the video uses dynamic pictures throughout, it relies entirely on animations and fails to present any realistic images, unlike the successful video, which shows static images of the finished product. The biggest problem with the video, however, is that it never shows viewers what the app will actually look like on their Apple Watch. Nonetheless, this video shares some characteristics with the successful video; for example, the production quality of the video is good, is presented in a 16:9 aspect, has a frame rate of 30 frames per second, and the audio is free of extraneous noise. In addition, music plays unobtrusively in the background, and it shows a logo for the product.

| Figure 3a. Problem statement

Narration Timing

|

| Figure 3b. Product description

Narration Timing

|

| Figure 3c. Creator introduction

Narration Timing

|

| Figure 3d. Appeal for funds

Narration Timing

|

The script of the video lacks many of the rhetorical appeals that appear in more successful videos, such as E1 (reference to professional expertise, practical experience, or prior success), P1 (the use of descriptive terms with an emotional narrative), P3 (a reference to claims of exclusivity), and L2 (information on the practical benefits of making donations). Like most videos, it provides some background information (L5 subtype) on a problem that the product claims to solve (‘forget to grab their MacBook and iPhone’) (see Figure 4a), and then mentions the features of the product (L1 subtype) that will help to solve this problem (‘she gets an alert’) (see Figure 4b). However, it neglects many of the other subtypes and lacks an ethos appeal. The viewer has no evidence that the company behind the product has had any prior success with other apps. Furthermore, very little reference is made to any of the pathos appeal subtypes. It does not claim to be a new or innovative product, and the closest that it comes to an emotional description is when the narrator claims that TetherMe is “an app you can’t leave behind.” Finally, it makes no direct appeal for funds but, instead, refers to its availability in the App Store (see Figure 4c). It is unclear why the project needs finance from crowdfunding, if it will soon be available to download. Several other failed videos end with a similar appeal to “download now” (Project 137, see Appendix A) or to “sign up today” (Project 142, see Appendix A).

| Figure 4a. Problem statement

Narration Timing

|

| Figure 4b. Product description

Narration Timing

|

| Figure 4c. Product availability

Narration Timing

|

Cross-cultural Analysis of Successful U.S. and Successful Non-U.S. Videos

Because Kickstarter began as a U.S. platform, many of the campaigns (n=17, 34%) analyzed in this study originated in the US. However, it is worth noting that many of the campaigns are also from creators based in other countries, particularly Europe (n=24, 48%). Both U.S. and non-U.S. campaigns included successful and failed projects. Table 2 presents the country of origin for the 50 videos (25 successful and 25 failed videos) examined in this study.

Table 2. The total number of campaigns examined in this study and their country of origin

| Country of Origin | Total # of Campaigns (%) | # of Successful Campaigns (%) | # of Failed Campaigns (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| US | 17 (34%) | 10 (40%) | 7 (28%) |

| UK | 10 (20%) | 3 (12%) | 7 (28%) |

| France | 4 (8%) | 3 (12%) | 1 (4%) |

| Australia | 3 (6%) | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) |

| Germany | 3 (6%) | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) |

| New Zealand | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (12%) |

| Italy | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) |

| Sweden | 2 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) |

| Canada | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| Netherlands | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Singapore | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| South Korea | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Spain | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| Switzerland | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

When we compared the physical characteristics of successful U.S. videos (n=10) with successful non-U.S. videos (n=15), one of the greatest differences related to the presence of the creator onscreen: 80% of successful U.S. videos (n=8) comprised an onscreen creator presentation compared with only 53% of non-U.S. videos (n=8). Another interesting difference related to the total number of static pictures, which appeared in 80% of successful U.S. videos (n=8) compared with 53% of non-U.S. videos (n=8). The majority of U.S. (n=7, 70%) and non-U.S. videos (n=12, 80%) showed the final product (see Table 3).

Table 3. Cross-cultural analysis of the physical characteristics of successful U.S. and non-U.S. videos

| Physical Characteristic | # of Successful U.S. Videos (%) | # of Successful non-U.S. Videos (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Aspect (4:3) | 2 (20%) | 1 (7%) |

| Aspect (16:9) | 8 (80%) | 13 (87%) |

| Total Static Pictures | 8 (80%) | 8 (53%) |

| Iconic static pictures | 7 (70%) | 6 (40%) |

| Analytic static pictures | 4 (40%) | 6 (40%) |

| Total dynamic pictures | 10 (100%) | 14 (93%) |

| Realistic dynamic pictures | 10 (100%) | 12 (80%) |

| Animations | 4 (40%) | 8 (53%) |

| Variable frame rate (sped up or slowed down) | 3 (30%) | 4 (27%) |

| Coloured pictures | 10 (100%) | 15 (100%) |

| Black and white pictures | 0 (0%) | 3 (20%) |

| Title | 2 (20%) | 3 (20%) |

| Logo | 7 (70%) | 12 (80%) |

| Final Product | 7 (70%) | 12 (80%) |

| Conceptual product (prototype) | 2 (20%) | 4 (27%) |

| Onscreen text (all) | 8 (80%) | 12 (80%) |

| Onscreen text instead of narration | 2 (20%) | 4 (27%) |

| Short texts | 8 (80%) | 10 (67%) |

| Long texts | 1 (10%) | 2 (13%) |

| Subtitles | 1 (10%) | 1 (7%) |

| Onscreen Creator Presentation | 8 (80%) | 8 (53%) |

| Offscreen creator narration | 7 (70%) | 9 (60%) |

| Music opening/closing only | 1 (10%) | 1 (7%) |

| Music throughout | 9 (90%) | 13 (87%) |

| Sound | 1 (10%) | 5 (33%) |

| Noise | 1 (10%) | 2 (13%) |

| Narrative speed (words/min) | 146wpm | 134wpm |

In terms of rhetorical appeals in spoken narration, we found that all (100%) successful U.S. videos (n=9) and 91% of successful non-U.S. videos (n=10) comprised the P1 (descriptive terms with an emotional narrative) subtype appeal and all U.S. and non-U.S. videos (100%) used the P2 (positive, emotionally rewarding implications) subtype appeal (n=9 and n=11, respectively) (see Table 4). However, it is interesting to note that non-U.S. videos comprised the P3 subtype (claims of exclusivity) more than twice as often (n=8, 73%) as U.S. videos (n=3, 33%). The majority (n=8, 89%) of U.S. videos and all (n=11, 100%) non-U.S. videos comprised the L1 subtype (factual data on the project, its features and functionality). Successful U.S. videos were more likely (n=6, 67%) to comprise the L4 subtype (information on why exactly the creator needs donations, and how he/she might use them) than non-U.S. videos (n=4, 36%). Marginally, more U.S. videos (n=7, 78%) used the E1 subtype (reference to professional expertise, practical experience, or prior success) than non-U.S. videos (n=8, 73%). Finally, we found that all (n=9, 100%) successful U.S. videos used the K2 (references to timeliness or a call to action to support the project) subtype appeal compared with 73% (n=8) of non-U.S. videos. Given the relatively small number of videos, we found no significant differences for the other ethos, logos, or kairos subtypes.

Table 4. Cross-cultural analysis of the rhetorical characteristics of successful US and non-US videos comprising spoken narration

| Rhetorical Subtype | # of Successful U.S. Videos (%) | # of Successful non-U.S. Videos (%) |

|---|---|---|

| E1: A reference to professional expertise, practical experience in technology, or prior success in technology relevant to the project. | 7 (78%) | 8 (73%) |

| E2: A reference to the involvement of a famous figure, organization, or product in technology, which is recognized by a large number of people. | 3 (33%) | 2 (18%) |

| E3: A reference to third-party recommendations, reviews, or testimonials. | 3 (33%) | 1 (9%) |

| P1: The use of descriptive terms with an emotional narrative such as ‘stunning’, ‘amazing’, ‘beautiful’, etc. | 9 (100%) | (91%) |

| P2: A reference to the positive, emotionally rewarding implications of supporting the project (e.g. ‘changing the way people experience video games forever’), or to the negative implications of the failure to support the project. | 9 (100%) | 11 (100%) |

| P3: A reference to claims of exclusivity of the product, such as by the word ‘unique’. | 3 (33%) | 8 (73%) |

| L1: Factual data on the product, its features, and functionality (such as a list of specifications). | 8 (89%) | 11 (100%) |

| L2: Information on the practical benefits of making donations (rewards offered and benefits to supporters) e.g. ‘with most pledges, we’ll also be sending out…’ | 3 (33%) | 2 (18%) |

| L3: Information on financial terms (affordability, discounts, guarantees of refund, shipping conditions, etc.). | 2 (22%) | 0 (0%) |

| L4: Information on why exactly the creators need donations, and how they will use the donations. | 6 (67%) | 4 (36%) |

| L5: General data (background information, problems that the product will solve, etc.). | 8 (89%) | 10 (91%) |

| K1: Contextual information on why the project fulfills a need for the current situation (e.g. ‘This is the only product that does X’ or ‘You will need this product when you want to do X’). | 6 (67%) | 10 (91%) |

| K2: Reference to timeliness or a call to action to support the project (e.g. there is a call to ‘act now’ or deadlines or goals are used). | 9 (100%) | 8 (73%) |

Conclusions, Limitations, and Recommendations for Future Research

Kickstarter projects are rarely for-profit projects; they are created by small entrepreneurs who are looking to cover the initial cost of manufacture for their product. Supporters often fund these campaigns because they want to be part of a real community and to feel like they are providing a valuable contribution to a project that would otherwise fail to receive finance.

The results from this study show that while successful and failed campaign videos shared many basic features, successful videos often contained elements that were lacking in many failed videos (e.g., they were more likely to demonstrate images of the final product than a prototype). Our findings suggest that if project campaigners spend time and effort incorporating these kinds of elements into their videos, the videos are more likely to be engaging and persuasive for potential investors. The distinguishing factors between successful and failed videos related to both the physical characteristics of the video and the rhetorical appeals used in the spoken narration.

The rhetorical appeals of successful videos help the viewers to empathize with the creators, and the video is a chance for the creators to showcase their passion for the project. The videos also reinforce the important role supporters play in funding the project. These qualities distinguish them from television commercials, for example, which are created on behalf of large for-profit organizations and in which all of the emphasis is on the product.

Table 5 presents a summary of the ideal characteristics for Kickstarter campaign videos for technology projects.

Table 5. Guidelines for the design of Kickstarter campaign videos for technology products based on the characteristics of successful videos

| # | Guideline |

|---|---|

| 1 | Use a combination of graphics

|

| 2 | Reduce onscreen text

|

| 3 | Use high quality visuals and audio materials

|

| 4 | Show the final product (if available) or prototype onscreen

|

| 5 | Use reasonable timing

|

| 6 | Use rhetorical appeals in the narrative

|

The inclusion of all these elements in a single project video may not necessarily be required. Indeed, there was not a single example among the 50 videos in this study where all of the characteristics were present at the same time. However, this profile could potentially be treated as a reference for developing campaign videos for technology products on crowdfunding platforms. Similarly, many of these findings are applicable to technical communication practitioners who want to develop engaging and persuasive videos to promote products via online outlets. These findings are also applicable to educators—for example, recommendations about the length of videos and the use of high quality visuals and audio are likely to be helpful in the creation of effective instructional videos. However, it is worth noting that instructional videos aim to inform their audience rather than persuade and so will differ in other ways, such as in the use of narrative and rhetorical appeals.

While the videos we analyzed were developed for technology projects specifically on the Kickstarter platform, future studies could investigate the usefulness of these findings and guidelines to projects from other categories, hosted on other platforms, and using different crowdfunding models. It is possible that the underlying dynamics of different crowdfunding categories and platforms vary (Belleflamme et al., 2014). For example, if attempting to source funds for an artistic project, the audience might expect a high-quality video; however, for other types of projects, the product might be more important than the video (Young, 2013). Furthermore, sub-categories within Kickstarter categories may also yield different results (e.g., apps might be more/less successful than robotics).

As this study examined videos within a relatively short timeframe (January to March 2016), a longer period could yield even more interesting results. Furthermore, this study does not examine where and how the Kickstarter campaigns were advertised. A search engine optimization (SEO) and social marketing campaign, for example, can also contribute to project success.

There are a number of possible avenues for future research. Researchers could investigate if the characteristics of zero-funded project videos differ from funded project videos or if the types of rhetorical appeals used determine the number of project backers. A larger dataset may yield more interesting results relating to cross-cultural differences between videos produced in different countries. Finally, future research could incorporate interviews and/or focus group studies to provide greater insights into the opinions of backers and video creators. It would be interesting to learn how people feel when watching crowdfunding campaign videos. Such research would provide even more valuable information on how to make crowdfunding videos more effective persuasive tools and how to make more effective videos for other purposes.

References

Agrawal, A., Catalini, C., & Goldfarb, A. (2010). The geography of crowdfunding. NET Institute Working Paper No. 10-08.

Alexander, K. P. (2013). The usability of print and online video instructions. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22(3), 237–259.

Almaraz, I. A., González, M. B., & Van-Wyck, C. (2013). Analysis of the campaign videos posted by the Third Sector on YouTube. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 68(1), 328.

Arguel, A., & Jamet, E. (2009). Using video and static pictures to improve learning of procedural contents. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(2), 354–359.

Atlas, R., Cornett, L., Lane, D. M., & Napier, H. A. (1997). The use of animation in software training: Pitfalls and benefits. In M. A. Quinones & A. Ehrenstein (Eds.), Training for 21st century technology: Applications of psychological research (pp. 281–302). Washington, DC: American Psychological Society.

Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T., & Schwienbacher, A. (2014). Crowdfunding: Tapping the right crowd. Venture Capital, 29(5), 313–333.

Benovic, C. (2016). Here are the 7 things you need to make a project video. The Kickstarter Blog. Retrieved from https://www.kickstarter.com/blog/here-are-the-7-things-you-need-to-make-a-project-video

Byg-Fabritius, E. U. T., & Willumsen, E. C. (2013). Kickstarter – a case study (Unpublished BSc thesis). Roskilde University, Denmark.

Cardon, M. S., Wincent, J., Singh, J., & Drnovsek, M. (2009). The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 511–532.

Carlsen, T. B. & Høgh, N. M. K. (2016). Crowdfunding: Predictors of success for entrepreneurial reward-based campaigns (Unpublished MSc thesis). Aarhus University, Denmark.

Chen, X.-P., Yao, X., & Kotha, S. (2009). Entrepreneur passion and preparedness in business plan presentations: A persuasion analysis of venture capitalists’ funding decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 52(1), 199–214.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2008). E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Cordova, A., Dolci, J., & Gianfrate, G. (2015). The determinants of crowdfunding success: Evidence from technology projects. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 181(2015), 115–124.

Courtney, C., Dutta, S., & Li. (2017). Resolving information asymmetry: Signally, endorsement, and crowdfunding success. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(2), 265–290.

Cowley, E. & Barron, C. (2008). When product placement goes wrong: The effects of program liking and placement prominence. Journal of Advertising, 37(1), 89–98.

Dowhal, D., Bist, G., Kohlmann, P., Musker, S., & Rogers, H. (1993). Producing a video on a technical subject: A guide. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 36(2), 62–69.

Drabløs, C. (2015). What influences crowdfunding campaign success (Unpublished MSc thesis). University of Agder, Norway.

Elliott, L. (2013). What makes a non-professional video go viral: A case study of “I’m farming and I grow it” (Unpublished MSc thesis). Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA.

English, K., Sweetser, K. D., & Ancu, M. (2011). YouTube-ification of political talk: An examination of persuasion appeals in viral video. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(6), 733–748.

Fenton, A. (2014). Weft QDA. Retrieved from http://www.pressure.to/qda/

Fernandes, R. (2013). Analysis of crowdfunding descriptions for technology projects (Unpublished BSc thesis). Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Fishman, E. (2016). How long should your next video be? Wistia. Retrieved from https://wistia.com/blog/optimal-video-length

Frydrych, D., Bock, A. J., Kinder, T., & Koeck, B. (2014). Exploring entrepreneurial legitimacy in reward-based crowdfunding. Venture Capital, 16(3), 247–269.

Gerber, E. M., & Hui, J. (2013). Crowdfunding: motivations and deterrents for participation. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 20(6), 1–32.

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM Conference on Learning at Scale (pp. 41–50). Atlanta, GA: ACM.

Hobbs, J., Grigore, G., & Molesworth, M. (2016). Success in the management of crowdfunding projects in the creative industries. Internet Research, 26(1), 146–166.

Höffler, T. N., & Leutner, D. (2007). Instructional animation versus static pictures: A meta-analysis. Learning and Instruction, 17(6), 722–738.

Hovland, C. I., & Weiss, W. (1951). The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly, 15(4), 635–650.

Hsieh, J.-K., Hsieh, Y. C., & Tang, Y. C. (2012). Exploring the disseminating behaviors of eWOM marketing: Persuasion in online video. Electronic Commerce Research, 12(2), 201–224.

Hughes, M., & Hayhoe, G. (2008). A research primer for technical communication: Methods, exemplars, and analyses. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group.

Kaminski, J., Jiang, Y., Piller, F., & Hopp, C. (2017). Do user entrepreneurs speak different? Applying natural language processing to crowdfunding videos. In Proceedings of the CHI’17 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Denver, CO: ACM.

Kämpfe, J., Sedlmeier, P., & Renkewitz, F. (2010). The impact of background music on adult listeners: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Music, 11(8), 1–25.

Kickstarter. (2018). Kickstarter stats. Kickstarter. Retrieved from https://www.kickstarter.com/help/stats

Kickstarter. (2017a). Campus. Kickstarter. Retrieved from https://www.kickstarter.com/campus

Kickstarter. (2017b). What tips do you have for making a great project video on a limited budget? Kickstarter. Retrieved from https://www.kickstarter.com/campus/questions/what-tips-do-you-have-for-making-a-great-project-video-on-a-limited-budget

Koch, J. A., & Siering, M. (2015). Crowdfunding success factors: The characteristics of successfully funded projects on crowdfunding platforms. In Proceedings of the 23rd European Conference on Information Systems. Munster, Germany.

Krause, A., Meyers, C., Irlbeck, E., & Chambers, T. (2015). What side are you on? An examination of the persuasive message factors in Proposition 37 videos on YouTube. In Proceedings of the Western AAAE Research Conference 2014. Kona, HI: American Association of Agricultural Education.

Lasswell, H. D. (1948). The structure and function of communication in society. The Communication of Ideas, 37, 117–130.

Lin, T. T. (2015). Online political participation and attitudes: Analysing election user-generated videos in Singapore. Communication Research and Practice, 1(2), 131–146.

Lindroos, T. (2016). Crowdfunding: Exploration of what influences campaign success (Unpublished MSc thesis). University of Helsinki, Finland.

MacNealy, M. S. (1999). Discourse or text analysis. In M. S. MacNealy (Ed.) Strategies for empirical research in writing (pp. 23–43). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Marelli, A. & Ordanini, A. (2016). What makes crowdfunding projects successful ‘before’ and ‘during’ the campaign? In D. Brüntje and O. Gajda (Eds.) Crowdfunding in Europe: State of the art in theory and practice (pp. 175–192). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Markel, M. (2012). Technical communication. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martins.

Marsh, C. (2007). Aristotelian causal analysis and creativity in copywriting toward a rapprochement between rhetoric and advertising. Written Communication, 24(2), 168–187.

Meyer, M. (2012). Aristotle’s rhetoric. Topoi, 31(1), 249–252.

Mitra, T., & Gilbert, E. (2014). The language that gets people to give: Phrases that predict success on Kickstarter. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (pp. 49–61). Baltimore, MD: ACM.

Mollick, E. R. (2014). The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 1–16.

Mollick, E. R. (2016). Containing multitudes: The many impacts of Kickstarter funding. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2808000

Morain, M., & Swarts, J. (2012). YouTutorial: A framework for assessing instructional online video. Technical Communication Quarterly, 21(1), 6–24.

National Center for Voice and Speech (n.d.). Voice qualities. Retrieved from http://www.ncvs.org/ncvs/tutorials/voiceprod/tutorial/quality.html.

Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Nielsen, J. (2004). Risks of quantitative studies. Nielsen Norman Group. Retrieved from http://www.useit.com/alertbox/20040301.html

Nielsen, J. (2005). Talking-head video is boring online. Nielsen Norman Group. Retrieved from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/talking-head-video-is-boring-online/

O’Connell, M., & Kurtz, D. (2012). How to make an awesome video. Kickstarter. Retrieved from https://www.kickstarter.com/blog/how-to-make-an-awesome-video

Plaisant, C., & Shneiderman, B. (2005). Show me! Guidelines for producing recorded demonstrations. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Symposium on Visual Languages and Human-Centric Computing (VL/HCC’05) (pp. 171–178). Dallas, TX: IEEE.

Ploetzner, R., & Lowe, R. (2012). A systematic characterisation of expository animations. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(3), 781–794.

Randomness and Integrity Services Ltd. (2016). True random number service. Retrieved from https://www.random.org/

Reyes, J., & Bahm, C. (2016). Crowdfunding: Applying collective indexing of emotions to campaign videos. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing Companion. San Francisco, CA: ACM.

Rieber, L. (2000). Computers, graphics, and learning. Madison, WI: Brown & Benchmark.

Rife, M. C. (2010). Ethos, pathos, logos, kairos: Using a rhetorical heuristic to mediate digital-survey recruitment strategies. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 53(3), 260–277.

Ritzenhein, D. N. (1998). Content analysis of fundraising letters. New Directions for Philanthropic Fundraising, 22(1), 23–36.

Smith, P. L., & Ragan, T. J. (1999). Instructional design. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Steinberg, S. M., & DeMaria, R. (2012). The crowdfunding bible: How to raise money for any startup, video game or project. Retrieved from http://www.crowdfundingguides.com/The%20Crowdfunding%20Bible.pdf

Strickler, Y. (2011). Shortening the Maximum Project Length. The Kickstarter blog. Retrieved from https://www.kickstarter.com/blog/shortening-the-maximum-project-length

Swarts, J. (2012). New modes of help: Best practices for instructional video. Technical Communication, 59(3), 195–206.

ten Hove, P. & van der Meij, H. (2015). Like it or not. What characterizes YouTube’s more popular instructional videos? Technical Communication, 62(1), 48–62.

Tirdatov, I. (2014). Web-based crowdfunding: Rhetoric of success. Technical Communication, 61(1), 3–24.

Tonks, D. G. (2002). Marketing as cooking: The return of the sophists. Journal of Marketing Management, 18(7–8), 803–822.

van der Meij, H., & van der Meij, J. (2013). Eight guidelines for the design of instructional videos for software training. Technical Communication, 60(3), 205–228.

Young, T. E. (2013). The everything guide to crowdfunding: Learn how to use social media for small-business funding. Avon, MA: Adams Media.

Welbourne, D. J., & Grant, W. J. (2015). Science communication on YouTube: Factors that affect channel and video popularity. Public Understanding of Science, 25(6), 706–718.

About the Authors

Aileen Cudmore is a technical writer and information developer from Cork, Ireland. She has a background in science writing and teaching, and holds a PhD in ecology from University College Cork. She received her MA in technical communication and e-learning from the University of Limerick, where she completed the research study described in this paper. She is available at aileencudmore@gmail.com.

Darina M. Slattery is Head of Technical Communication and Instructional Design at the University of Limerick, where she has also directed graduate programs. Her teaching and research interests include e-learning, technical communication, learning analytics, and virtual teams. She has published widely and is a reviewer for several international journals, including the British Journal of Educational Technology, IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, and Communication Design Quarterly. Her co-authored book Virtual Teams in Higher Education: A Handbook for Students and Teachers was published in 2016. She is available at Darina.Slattery@ul.ie.

Manuscript received 8 September 2017, revised 1 February 2018; accepted 19 April 2018.

Appendix A. List of videos included in final analysis

Appendix B. Codebook for recording the external properties of videos

Unit of data collection: Campaign videos listed in Appendix A, which were randomly selected from the Kickstarter technology projects that were launched in the first three months of 2016.

Project ID: Fill in the video’s ID number.

Project title: Give the title of the Kickstarter project.

Project success: Indicate whether the project reached its funding goal or not.

- Failed. The project failed to reach its funding goal.

- Successful. The project succeeded in reaching its funding goal.

URL: Give the website address of the project page.

Creator: Give the name of the project creator. All projects must be from first-time creators.

Campaign start date: Give the date on which the creator launched the project on Kickstarter.

Campaign duration: Report the total length of the campaign, in days.

Currency: Report the currency used for the project.

- Australian Dollar

- British Pound

- Canadian Dollar

- Euro

- New Zealand Dollar

- Swedish Krona

- Swiss Franc

- US Dollar