By Kim Sydow Campbell, Ryan K. Boettger, and Val Swisher

Abstract

Purpose: This teaching case examines challenges in developing technical communication students as organizational leaders managing content strategy through analysis of a graduate course incorporating a client project.

Method: Forty-five graduate students enrolled in a content strategy course conducted content audits and assessments for six clients. Their final strategic roadmap reports were analyzed to determine their aptitude for aligning content strategies with business goals.

Results: While students adeptly identified technical content quality issues, the majority struggled to connect these to business implications. A minority of students explicitly linked their strategic recommendations to business metrics, such as revenue growth. This outcome suggests a deficiency in achieving the course’s intent to instill a business-oriented approach to content strategy.

Conclusion: The case identifies several challenges, including client maturity levels, the intricacy of business contexts, and the ambitious scope of the course’s objectives. Proposed enhancements involve restructuring client interaction, integrating more industry expertise, focusing the project’s reporting component, and refining the course’s aims. These measures aim to strengthen the strategic business thinking and leadership capabilities of technical communication students.

Keywords: Content Strategy, Organizational Leadership, Pedagogy, Content Operations

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Technical communication students, like their professional counterparts, struggle to connect content issues with business causes and effects.

- To foster technical communication leadership, content strategy coursework should emphasize content as a business asset.

- Client projects in content strategy education are crucial for real-world experience, connecting content strategy and tactics with business goals.

- Collaboration with an industry professional when designing a content strategy course is highly recommended.

- Multiple content strategy courses would allow more emphasis on the various phases of such projects, especially the earliest discovery phase which focuses on the connection between content issues and business issues, including processes and technologies for managing and delivering technical content (i.e., ContentOps).

- Integrating business courses such as marketing research or organizational behavior into the curriculum might better prepare students for content strategy roles.

Introduction

Jack Molisani, who specializes in recruiting for technical communication positions, wrote that the number one business skill needed by job candidates is the ability to describe their value in terms that support their employers’ goals:

It is a safe assumption to say many technical communicators don’t truly understand that management’s job is to decrease costs and increase revenue and market share, and therefore those technical communicators can’t effectively communicate how they add to their organization’s bottom line. (Molisani, 2021)

We could not agree more strongly.

Molisani’s point is corroborated by industry surveys: 33% of technical communication practitioners could not report the value they provided to their employer in 2017 (Ludwig, 2021a), and 72% said they were not measured against specific content goals by their employer in 2020 (Ludwig, 2021b). When technical communicators cannot demonstrate how they contribute to their organization’s goals, they lack business knowledge, which has many well-known, negative consequences that include lack of respect for the profession. Complaints about lack of respect for the technical communicator’s role or skills are longstanding: limited organizational input (Rosselot-Merritt, 2020), poor treatment by internal customers (Rosende, 2016), stress from excessive workloads (Singer, 2001), inadequate advancement opportunities (Walsh, 2010), and so on. The complaints are both longstanding (Abel, 2007; Johnson, 2012) and global (Lopes & Godefroy, 2017). The perceived lack of respect and lack of business understanding signal a leadership vacuum within technical communication.

Building a better understanding of content and content creators as a business asset is a natural fit within content strategy coursework in technical communication degree programs. Content strategy professionals with technical communication roots have historically incorporated business value within their definitions of content strategy (e.g., Bailie & Urbina, 2013; O’Keefe et al., 2019; Rockley & Cooper, 2012; Swisher, 2014). Unlike their counterparts in marketing content strategy, they have dealt with the lack of budget for, and the resulting need for efficiency in, managing and delivering technical content in large organizations (i.e., ContentOps) since the beginning (Rockley & Cooper, 2012). In addition, there is evidence that more technical communicators are transitioning into content strategy work and that this more strategic role may put them in a position to earn higher salaries (Flanagan et al., 2022) as well as to avoid displacement by AI (Johnson, 2023). Trends also indicate technical communicators are rebranding themselves with alternate job titles—content designer, content specialist, content strategist—in attempts to better signal their skills in strategic thinking and business acumen (Albers, 2016). The strategic nature of content strategy work naturally identifies the content strategist as a leader.

In this paper, we share what we have learned about the challenges encountered in developing technical communication leaders in a content strategy course. We begin by summarizing our graduate-level, content strategy course. In particular, we identify the course materials that highlighted the status of content as a business asset. We then describe the six client projects completed by 45 students who took the course between 2021–2023. Finally, we gauge the potential of those 45 students to lead content strategy development at the conclusion of their projects by reporting and analyzing the recommendations they made in their strategic roadmap reports using the maturity model for content strategy development (Campbell & Swisher, 2023). We end by concluding that our goal of producing organizational content leaders remains a challenge and by offering avenues for overcoming it in the future.

Course Design and Project Overview

Our master’s-level course provides advanced study of content strategy for technical communicators, with six learning goals. The number one learning goal explicitly speaks to applying knowledge of business goals to technical content.

- Discussing technical content as a business asset and presenting content strategy development as a means of increasing business value.

- Gathering and organizing descriptive and quantitative/qualitative data about content performance through interviews of stakeholders, review of existing artifacts (e.g., personas, customer journey maps, etc.), and use of software tools (e.g., Excel, Google Analytics, etc.).

- Analyzing quantitative/qualitative data about content performance to achieve strategic insights.

- Applying project management tools/techniques (e.g., charter, WBS, Kanban, Trello, status updates, etc.) during a team content strategy project.

- Reflecting on content strategy knowledge and skill development through written blog posts in a content management system (CMS) like WordPress.

- Demonstrating professionalism through timely submission of deliverables, constructive interpersonal interactions, acceptance of feedback, and upholding team commitments.

These learning goals dovetail with the skills identified as most critical in content strategy (Flanagan et al., 2022). It is important to note that we provide a separate course in digital literacies, which is responsible for learning goals in what has typically been labeled as content management in technical communication (Bridgeford, 2020; Pullman & Gu, 2020).

Our content strategy course is required for graduate students pursuing both the Master of Arts in Professional and Technical Communication and the Graduate Academic Certificate in Technical Writing. Between 2021 and 2023, the course was delivered four times in an eight-week, asynchronous online format, which is typical for courses in both programs. Forty-five students completed the course in this timeframe. They represented diverse undergraduate majors, from technical communication to English to journalism to secondary education to information technology. The types and amount of work experience among students were also diverse. A few students enrolled directly after finishing their undergraduate degree. A handful of students were supplementing their credentials as current college English teachers to begin teaching technical writing. However, most students were transitioning from their current careers to one in technical communication.

Instructional Materials Emphasizing Content as a Business Asset

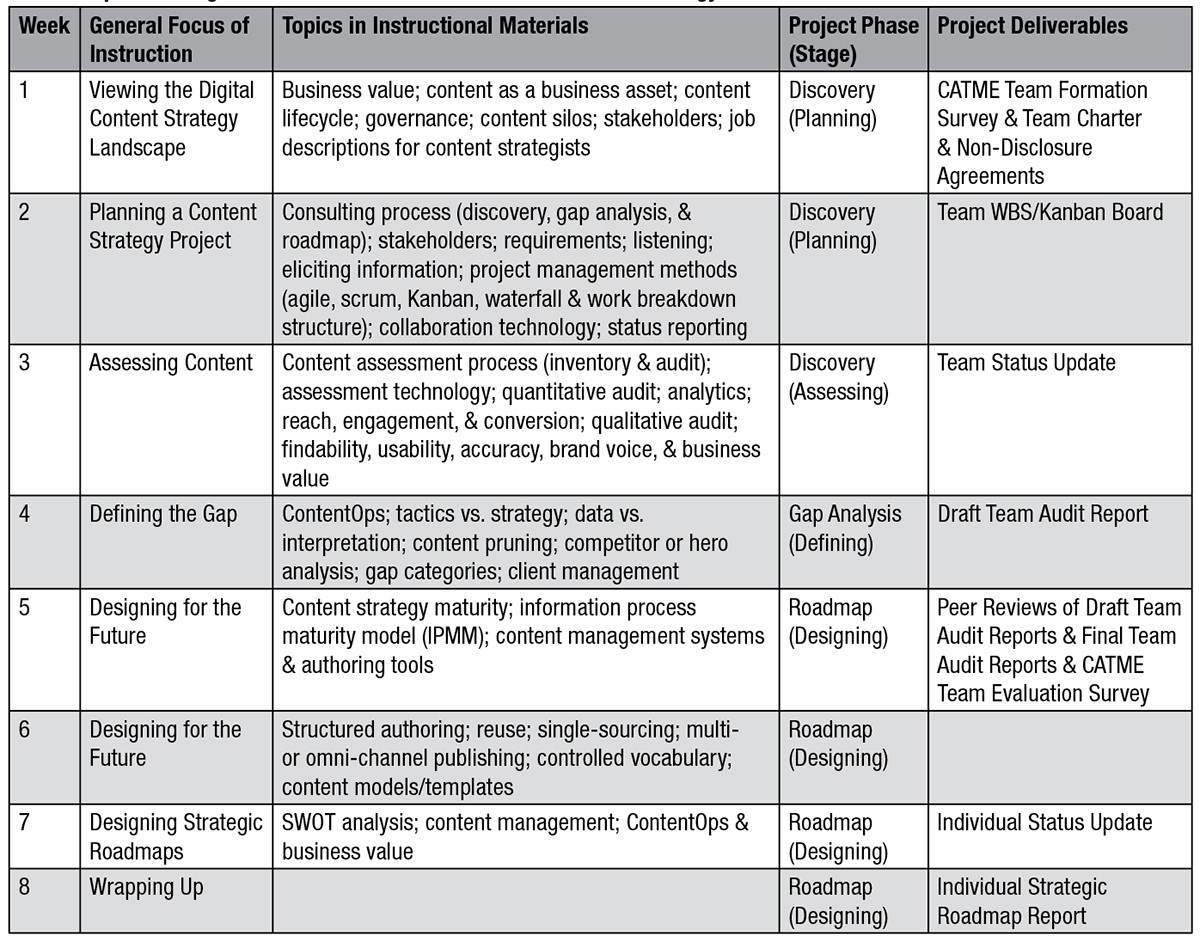

Instructional materials in the course included an industry-focused, project-organized, content strategy book (Nichols, 2015). Additional industry-focused readings, webinars, and podcasts were assigned throughout the eight weeks, with major topics summarized in Table 1.

To convey the course’s emphasis on content as a business asset, our number one learning goal, we detail below how four types of required, instructional material were used. First, one instructor video lecture introduced the learning objectives of the course, of which the first is understanding content as a business asset. Another explains several business concepts:

- Business value is understood as “profit” (see Figure 1). An extended definition and example are used.

- Unique value propositions explain how an organization’s product (or service) benefits its customers and how it’s different from what competitors offer. An example using organizational content is provided.

- Organizational silos typically result in content chaos, where accuracy, duplication and inconsistency between business units are the norm.

- Organizational hierarchy and the placement of content creators within an organization influence content governance (or its lack thereof).

For all organizations, including those that are nonprofit or public, profitability is key. More “profit” means expanding services for clients (Gunning, 2014) in addition to more money for owners or dividends for shareholders.

Second, the readings from Nichols (2015) described content strategy’s relation to not only the content experience of users or customers but also to ContentOps (i.e., the organizational people, processes, and technologies used to create and manage content) and content governance (i.e., who makes decisions about it).

Third, recorded videos of professionals made several points about the relation between content and business. For instance, one clarified that content strategy is not owned by marketing units or professionals despite their adoption of the phrase to mean “content marketing” (Halvorson, 2020). In another instance, a professional stated that strategy is the analysis phase of a business problem that determines how content can lead to corporate success (Bailie, 2020). In addition, our first client meeting showed the client representative introducing their organization, its customers, its goals, and its content team to the students.

Fourth, maturity models were introduced to focus specifically on content as a business asset. In Week 5 of the course, readings and the instructor’s video-lecture taught students about maturity models and expanded on how to think about content strategically within an organization. We offer below more detail on how students learned to identify promising directions for content strategy based on their perceptions of client maturity.

The Content Strategy Development Maturity Model

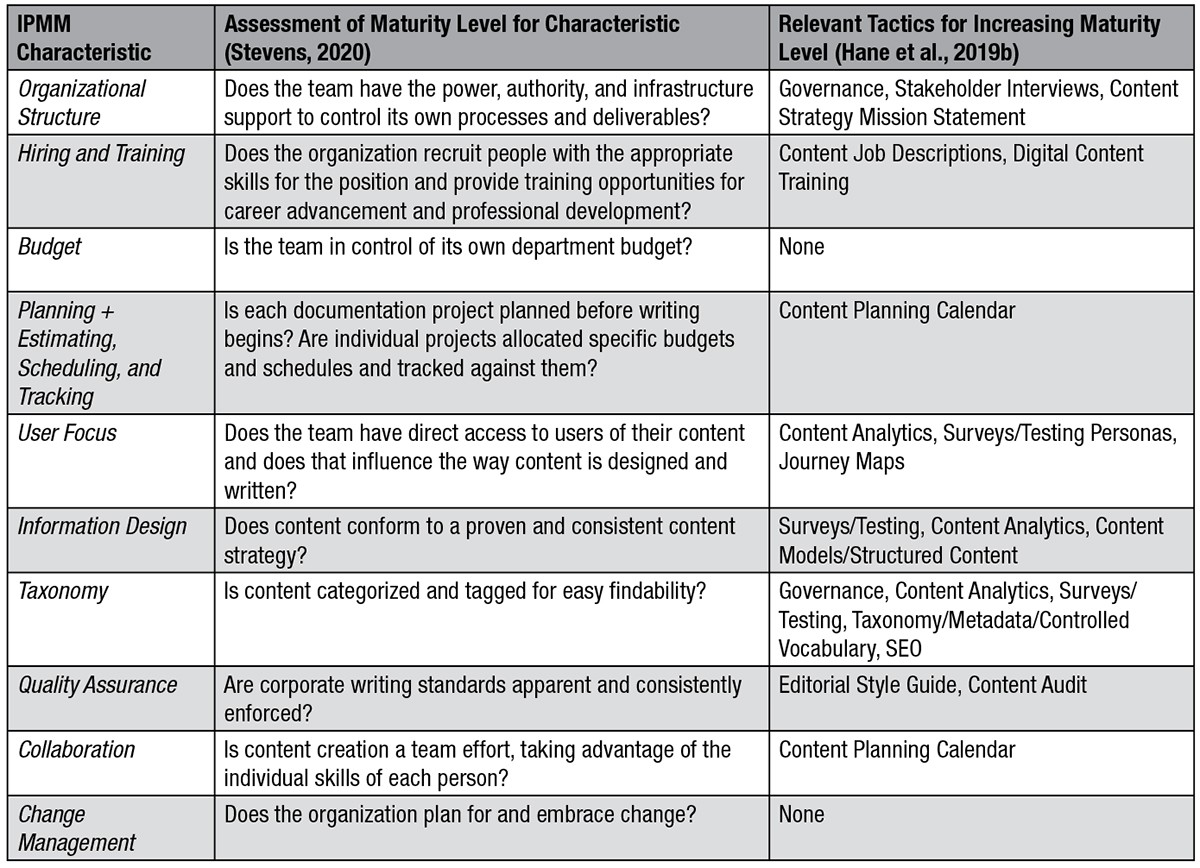

Students read about Campbell and Swisher’s (2023) maturity model for content strategy development, which is reproduced in Table 2. As Hackos wrote, “The purpose of a process maturity model is to provide guidance for organizations to establish best practices that promote excellence and ensure cost-effective outcomes” (2017, p. 1).

Campbell and Swisher (2023) explain their model and, in particular, the relationship between each of the IPMM characteristics in column one, the content tactics in column three, and business profitability with an extensive discussion of ContentOps. While we cannot repeat their discussion here, we will offer one critical example. If organizational structure for content work is not sufficiently mature (e.g., content professionals have little authority to influence processes), it must be the top priority in developing a strategic plan for content. The strategy must rely on a business case about the impact of centralized content authority on profitability to influence leaders. With evidence of lower profitability due to (a) lost revenue associated with content effectiveness and (b) increased expenses associated with the inefficiency of ContentOps (creating, managing, and distributing content), business leaders will be persuaded to pay attention to content in meaningful ways.

As Table 2 shows, the model displays tactics as the outcome of strategy (Bailie, 2024). For instance, one tactic for increasing maturity in organizational structure is governance, which can mean new policies for ContentOps across the organization that ultimately improve productivity. Students learned about governance throughout the course through a variety of instructional materials. Another tactic for increasing maturity in organizational structure is stakeholder interviews. These interviews are valuable as a means of building a business case for better governance by uncovering evidence of existing content issues—and potential allies within the organization (e.g., customer support). Students practiced some of this interviewing in the four client meetings although they were limited in meeting with only a single type of stakeholder.

In sum, instructional materials and course experiences were designed to expose the connections between the business and content. Evia recently wrote that ContentOps

does not aim to commodify all communications in an organization. The goals, instead, should be to perceive and treat valuable pieces of content as business assets and to establish and maintain workflows that implement a strategy for the automation of routine tasks related to content creation and processing (2024, p. 7).

This was precisely the goal in our content strategy course. As a result of the instructional materials and their experience completing a content audit, we expected students to demonstrate competency in the number one learning goal by the end of the course.

The Client Project and Major Deliverables

Many content creation educators (Spring & Nesterenko, 2018), including those in technical and professional communication (Campbell & Katan, 2022; Dumlao, 2022; Howard, 2020; Kastman Breuch, 2001; Kimme Hea & Wendler Shah, 2016; Willerton, 2013) have reported on their use of client projects to introduce students to the contexts within which they will work after graduation. We also designed our content strategy course around a client project, envisioning that students would come to understand more about content strategy by working closely with authentic content and the people in organizations who own it.

In Week 1, students read and viewed a video with an overview of the client project and samples of the major deliverables. These explained that the course’s instructional topics and deliverables (refer to Table 1) would move them through a client-based, content strategy project comprised of three phases based on the frameworks used by content strategy consultants (Bailie, 2020; Nichols, 2015; O’Keefe et al., 2019):

- Discovery: Teams planned their work and then inventoried and audited or assessed the client’s content during this phase.

- Gap Analysis: Teams defined the gap between the client’s current state (based on their content assessment) and the client’s goals in this phase. For Discovery and Gap Analysis project phases, students were divided into small teams of two to four, based primarily on their responses about scheduling virtual teamwork using CATME Team-Maker (Layton et al., 2010). Team content assessment findings and gap analysis were delivered to clients and the instructor as a spreadsheet and brief report at the end of Week 5.

- Roadmap: Individual students designed a strategic report for their client, recommending strategies and tactics, based on their prior team efforts in the earlier phases of the project. Roadmap reports were delivered to the instructor at the end of Week 8.

In brief, the two major deliverables connected with the client project were the content assessment spreadsheet with its brief report at the end of the gap analysis phase and the strategic report at the end of the roadmap phase. Because it was crafted by individual students and focused on content as a business asset, the strategic roadmap report provided an excellent measure of the 45 students’ ability to lead ContentOps within an organizational context.

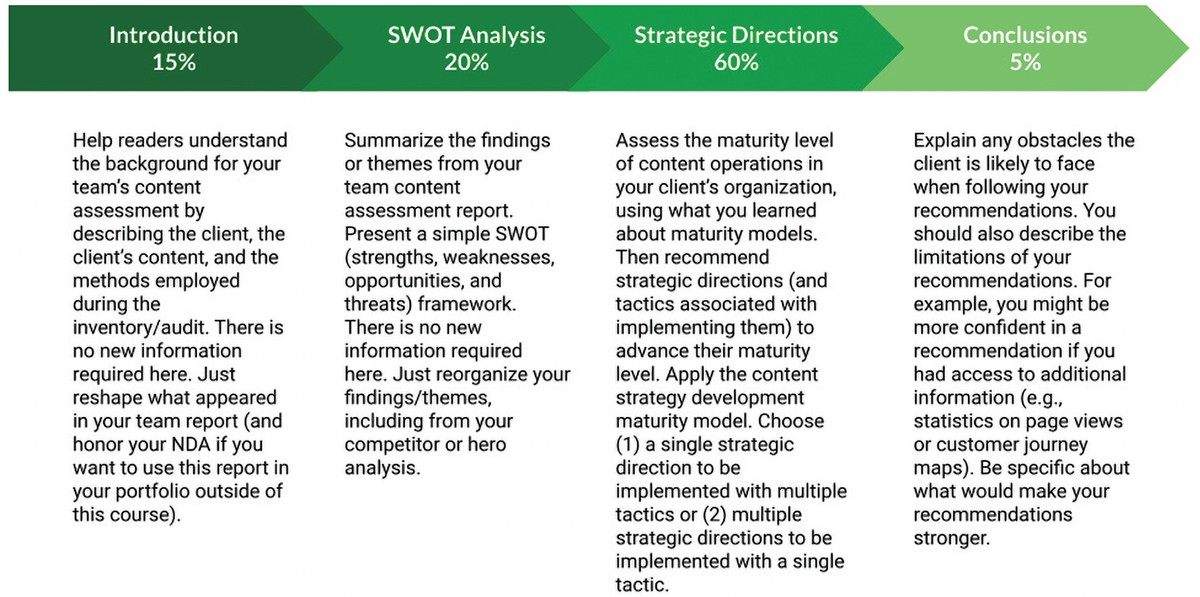

The individual roadmap reports required four major types of information, described to students as shown in Figure 2. Thus, these reports offered data for assessing the success of our client-based project in meeting the #1 learning goal of the course:

- Research Question: Do students demonstrate knowledge of content as a business asset and present content strategy development as a means of increasing business value in a report after a client-based content audit?

With adequate knowledge of content as a business asset, we hoped our students would select strategic directions and content tactics, as well as justify those selections, based on their relative value to the client’s business goals. Our research was exempt from IRB review because it involved data from existing instructor records. In addition, the data contained no personally identifiable information because it was previously anonymized for grading purposes by the instructor.

The Clients and Content for The Content Strategy Project

Students performed their content strategy work for one of four business clients assigned to them randomly by the course instructor. Clients were recruited by the instructor, who leveraged contacts with alumni of the department’s degree programs. All students signed a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) before gaining access to client information.

When clients initially agreed to participate, the instructor requested the following types of information to support students’ content strategy work:

- An organizational representative who could provide or develop (with help):

- A list of business pain points related to content (e.g., cost of or time to do updates, cost of translation, number of customer complaints due to findability or inconsistencies, etc.).

- A content vision or goal.

- Answers to questions about content maturity and other issues.

- Access to the items listed below.

- A body of content. Ideally, it would be inter-related content but “owned” by separate units (customer support, sales, training, marketing, etc.).

- Data on content consumption (e.g., Google Analytics, MozBar, etc.).

- Existing style guides, personas, and customer journey maps related to the content.

Client representatives participated in four synchronous, virtual meetings with specific purposes based on the stage of the students’ work on the content strategy project. Week 1: Introduce your company, products, customers, and competitors, as well as your role within the company. Week 2: Provide project content details, including business goals or KPIs (Key Performance Indicators). Week 3: Describe your content team workload and your access to users or customer data. Explain content governance and workflow or lifecycle. Answer student questions based on their content inventory and audit activities. Week 4: Answer student questions based on their competitor and gap analysis activities. Because students were enrolled in an asynchronous, online course, virtual meetings were scheduled based on client availability. Students were invited to attend live or to submit questions in advance and to watch recorded meetings afterward.

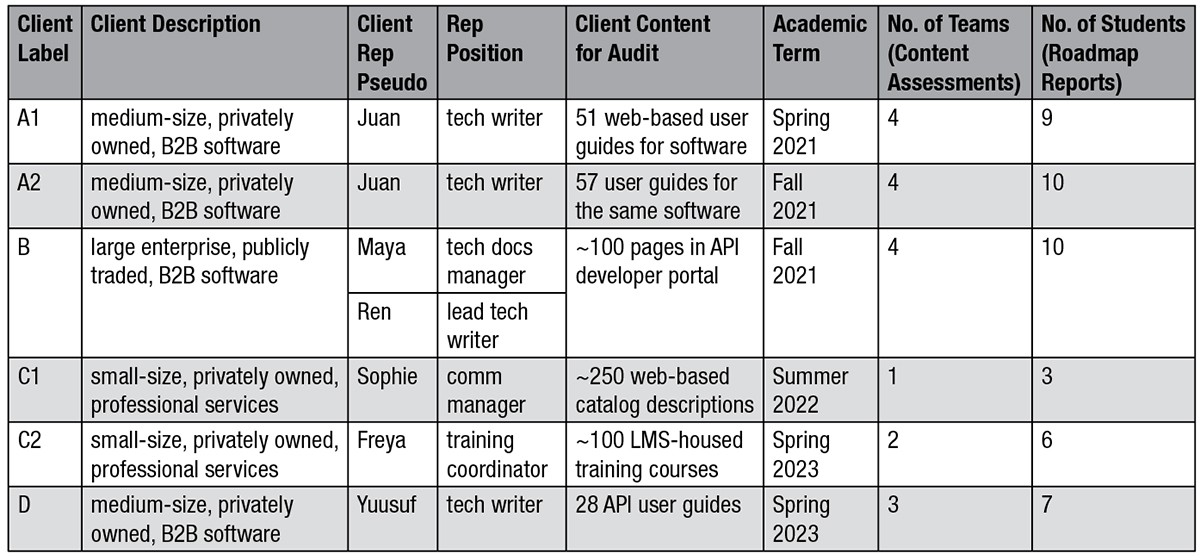

Details for the client projects are summarized using pseudonyms in Table 3. As indicated in Table 3, the clients represented diverse industries, from a publicly traded B2B software enterprise to a small professional services firm. The content clients supplied for project work also varied, including user guides, developer documentation, product descriptions, and professional development trainings. We should note that two of the same business clients participated in the project in different terms. For Client A, the student experience was nearly identical in both terms. However, the client supplied two different sets of user guides with distinct functions for the same software product. For Client C, the student experience was distinct in each term, with two different client representatives representing distinct content types within the same organization.

Results and Interpretation

We begin by sharing student perceptions of the content strategy project. Of the 28 whose anonymous comments were available from the institutionally administered course survey, 12 students named the project as what contributed most to their learning during the course and made positive comments like this one: “The content audit and assessment contributed most as it gave real experience in how to complete one and what could be expected when doing this type of work for a client.” The only negative project comments came from two students, who said the immensity of the project detracted from their learning.

Although there is much we could say when sharing our findings from these client projects, we limit ourselves to examining two topics that help to answer our research question focused on student competency in the number one learning goal: presenting content strategy development as a means of increasing business value. First, we discuss the maturity levels of our six clients and the potential challenge that presented in promoting the idea of content as a business asset. Second, we present some illuminating examples of student successes (and a few failures) in treating content strategy development as a means of increasing business value.

Client Maturity Levels

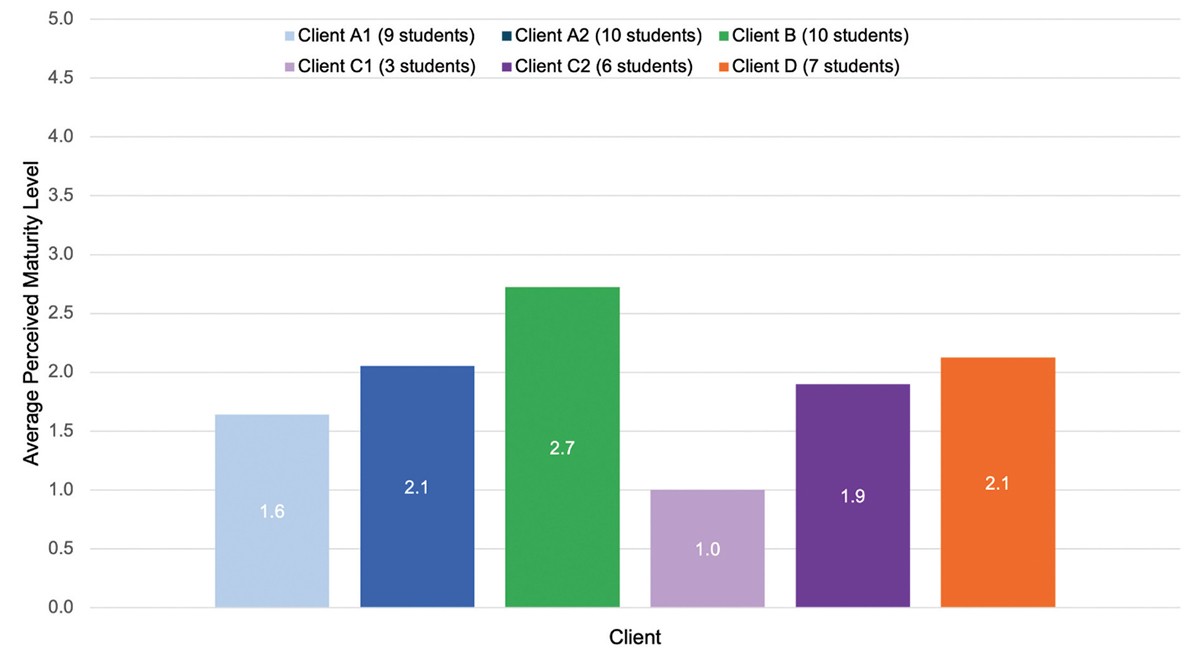

In Figure 3, we display each client’s maturity level, calculated as the average rating by the students who worked with them, with 5 representing the highest level. For inclusion in their report, students chose a scale from the maturity models covered in their instructional materials (Hackos, 2017; Hane et al., 2019b; Jones, 2018; Kunz, 2015). The highest levels of maturity in all models integrate ContentOps and the rest of the organization. For example, Hane et al. (2019b) describe their highest level as “Organizations that are focused on the environment, collaboration, and continually iterating, and are using 14 or more tactics…with greater weight on three tactics: analytics, governance, and content planning calendar…” (p. 10) where “People work together with shared goals, no longer operating in hierarchical organizational silos” (p. 11).

Our results demonstrate that, on average, students judged all clients as relatively immature, with Client B (a B2B software enterprise producing APIs) perceived as the most mature of the six but with an average rating of 2.7, just approaching the midpoint of the scale. Although Client C1 was rated lowest at 1.0, they were judged by only three students, who formed a single team for their content strategy project. The six students who worked with Client C2, however, rated the organization higher at 1.9 but still at a low level of maturity. Client C was a small professional services firm that provided training.

In general, we agree with the student ratings of client maturity. In fact, relatively low levels of maturity appear to be the norm in ContentOps. Research reported by two content strategy consulting groups (Hane et al., 2019b; Jones, 2019) found levels at the midpoint or higher were rare. As Bailie and Urbina wrote, “unless your organization is a newspaper or [has] a business model where producing content is your primary product, there has likely been little impetus to pay much attention to content” (2013, p. 214). This presents a challenge for instructors of content strategy because lower maturity levels mean the client representatives should be less aware of the connection between content and business issues. We did what we could to elicit that information from clients who participated in our requests for existing data and in our questions for client meetings. Not surprisingly, we cannot claim that the client representatives easily met our goal of sharing how they treat content as a business asset. In the analysis of student roadmap reports that follows, we did find some student successes despite our clients’ low maturity levels.

Strategic Directions and Tactics in Roadmap Reports

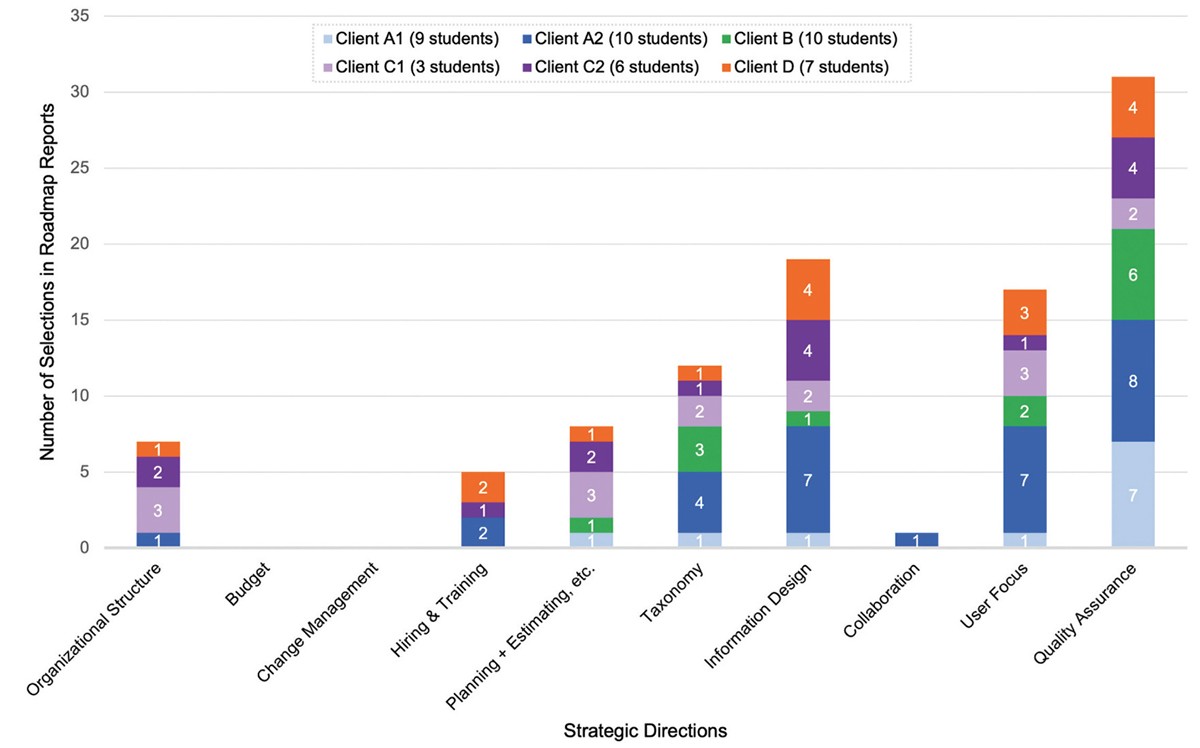

Asking students to select strategic directions and tactics for their clients from the maturity model for content strategy development in the strategic roadmap report allowed us to investigate what and how much students learned about treating content as a business asset. Figure 4 displays the distribution of all strategic directions for the six client projects as selected by the 45 students in their reports.

Quality assurance was the most common strategy selected by students. On the one hand, this result means that students in the course showed significant awareness of the use of style guides as a tactic for content quality assurance (refer to Table 2). All six clients received recommendations to use or improve style guides from a majority of the students who worked with them on a content project. In particular, 15 of the 19 (79%) students working with Clients A1 and A2 recommended assuring content quality with style guides.

On the other hand, style guides do not directly impact the client’s business outcomes. One student justified their focus on quality assurance by noting that Client A2 often brings in subject-matter experts (SMEs) to write user guides because the content workload is too great for the two technical writers. The student reasoned that the SMEs need a style guide, along with training, to produce higher-quality content. Unfortunately, we see the most critical business implication as taking SMEs away from the jobs they were hired to do. How much did it cost the company to have these employees create content? Does it make good business/financial sense to have people whose primary job is not technical writing do the writing? The student viewed the situation through a tiny lens of style guides and editing to optimize content quality. This was truly a lost opportunity, signaling the student did not connect their content findings to business causes and effects. Without that insight, the student would be unlikely to function as an effective content leader within an organization.

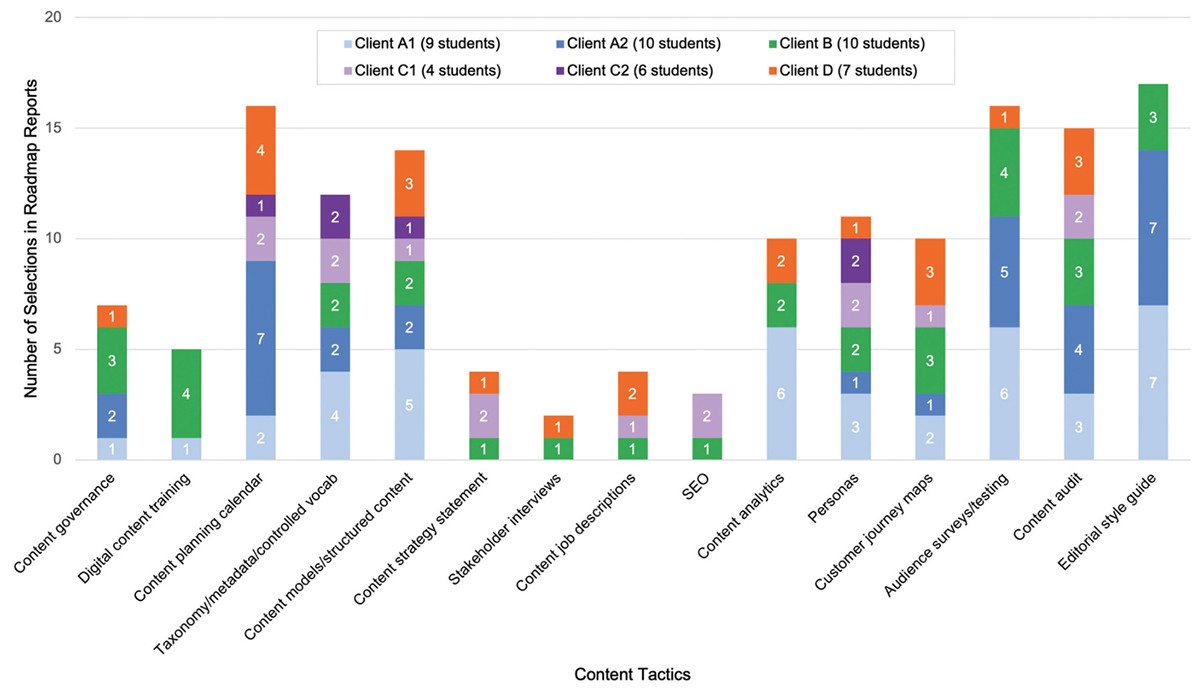

Information design was the second most common strategy selected by students for their clients. Again, this result means that students in the course recognized its importance in developing a content strategy. Although all six clients received recommendations to follow this strategic direction, Figure 5 shows that most students focused on audience surveys or testing tactics for implementing that strategy while fewer recommended its associated tactics of content models or structured authoring (see Table 2).

As we described above, the strategic directions and tactics in the maturity model for content strategy development vary in the directness with which they connect to business outcomes. The information design strategy impacts content directly but an organization indirectly. Adopting an information design strategy that implements structured authoring demonstrates an unequivocal focus on operational efficiency (Andersen & Batova, 2015; Dayton & Hopper, 2010; Hart-Davidson, 2010; Pullman & Gu, 2007). Students learned about these tactics primarily in Week 6, when tactics were the sole focus of course materials.

To explore an example for Client C2, 4 of the 6 (67%) students working with that client recommended information design as a strategic direction; however, they focused almost exclusively on adopting templates for content types to increase consistency. Only one student specifically suggested structured authoring as a tactic for implementing that strategy. Sadly, they also argued the value of using structured authoring was increased content consistency. No student who worked with Client C2 mentioned structured authoring or content models as a means of increasing business outcomes by cutting business costs through content reuse—despite its pointed emphasis in Week 7 of the course. Yet this is the number one reason organizations adopt it (Rockley & Cooper, 2012; Swisher & Preciado, 2021). This apparent lack of insight would make it difficult to lead a content group effectively within an organization.

We remind readers that all master’s and many graduate certificate students in these programs complete a separate digital literacies course in which they create modular content with DITA-like standards and then reuse some of it to publish in multiple channels from a single source in a component content management system (CCMS). The content strategy course is intended to focus on why or when—not how—to use content authored and managed as components. Some of the 45 students in the content strategy course had completed the digital literacies course before taking the one in content strategy. Nevertheless, they ignored the business potential of structured authoring for creating efficiency and increasing profits for their client.

The strategic direction of user focus was also a commonly selected strategy of students in their reports. One such student hinted at the business value of Client D’s content by stating that more user-focused content, as used by a competitor, could help them attract, satisfy, and retain customers. That student also listed several business-focused questions in the report’s conclusion as potential limitations of her recommendations. In this particular case, we might guess the client’s low maturity level created an insurmountable obstacle in the form of missing information that prevented this student from fully committing to treating their content as a business asset. However, another student mentioned the potential of increases to Client D’s key performance indicator of annual recurring revenue if they embedded a user-feedback option in their published guides. This student clearly and directly connected the strategic direction of user focus to business goals. Thus, we cannot attribute the former student’s lapse to the low maturity of their client.

As Figure 4 shows, the tactic of implementing a content planning calendar was a popular choice among students for five of six clients. Most students discussed this tactic as a means of implementing the planning + estimating strategy by removing outdated content to enhance user experience. Again, the student focus was on content quality. However, one student working with Client D mentioned the potential of content planning to support three strategic directions: planning + estimating, collaboration, and organizational structure. (This student was also the only one to present a single tactic as a means of implementing multiple strategic directions.) The student, who connected a content calendar with getting everyone in the organization on the same page for all ContentOps, also mentioning its impact on lifecycle planning, information design, and quality assurance, was exceptionally astute. We are confident this student can lead a content team based on their roadmap report because they connected content with business concerns.

Interestingly, five of the nine students who worked with Client C1 or C2 recommended organizational structure as a strategic direction. We hope the fact that their client was rated as the least mature means they recognized that foundational organizational changes were imperative to address content issues. One student who worked with Client C1 emphasized the tactic of content governance in her discussion of addressing organizational structure, including the need for a single owner of content and a prescribed content lifecycle. Hackos categorized organizational structure as the “first and most pivotal” characteristic of maturity for a technical content team because all other characteristics rely upon it (2007, p. 55). While a few other students mentioned content lifecycles, not one recognized that a content leader was paramount to addressing content issues within that organization. This strategic direction was applicable to most, if not all, of these six clients because of their low maturity levels. A single student demonstrated the ability to recognize organizational structure as the most critical aspect of their recommended content strategy. We should note that a previous analysis of tactic selections by hundreds of professionals revealed no identifiable pattern of adoption based on maturity level (Campbell & Swisher, 2023).

The least recommended strategy was collaboration. A single student presented it as of potential to Client A1. We are somewhat surprised as students regularly expand their thinking about future careers after the content strategy course and have specifically mentioned a newly recognized interest in working across organizational units. We interpret that attitude as highly desirable because Batova (2018) found it was a key motivator for technical writers who successfully managed the adoption of a component content management system in their organization. Recognizing the business value of collaboration is a prerequisite to effective leadership in organizations (Hackos, 2017). Effective collaboration is needed to develop content governance and effective workflows (Swisher & Preciado, 2021).

In general, our students were able to identify issues with technical content quality, and they understood how to address those issues by conducting user tests, implementing a planning calendar, adopting style guides, and so on (Fig. 4). This result is gratifying but not surprising as most, if not all, of the students’ coursework emphasized their future roles as content creators or designers. A few students were also capable of identifying and addressing content management issues and recommending their client become more mature by developing a taxonomy or metadata plan. We consider this encouraging news. The students who recommended such a strategy demonstrated useful knowledge for leading a technical communication team in industry. Overall, however, we are disappointed the students failed to discuss the business causes or effects surrounding the content issues they identified during the project. Instead, they conflated content and process problems. They focused almost exclusively on issues of content quality, usually characterized as a function of consistency, without connecting them to organizational issues. We believe this signals there was limited success in meeting our number one learning goal for students to think about content as a business asset and, thereby, to demonstrate their potential as leaders.

Challenges in the Client-Based Content Strategy Project

In the hope that others can learn from our experience, we present the most challenging issues we faced in teaching content strategy and how we hope to address them in the future.

Challenge 1: Client maturity

Clients might be screened to include only those with information about business pain points related to content or with specific KPIs related to the technical content team’s performance. In other words, the instructor might seek only clients with a higher maturity level, which would more likely reinforce the connection between content and its business value. We have limited confidence in this option for improving student learning. Any instructor who implements client-based course projects knows the intricacies and difficulties of client recruitment (Howard, 2020). The relatively low number of sophisticated content teams (Hane et al., 2019a; Jones, 2019) would exacerbate those difficulties. In addition, we found overwhelming evidence that our students were hyper-focused on content problems and missed existing opportunities to connect content and business issues despite low client maturity.

The one immediate change we advocate is revising the detail and order of agendas for client meetings. Clients were directed to discuss their organizational context, including business goals and key performance indicators, in Meeting 2. That agenda can easily be moved to Meeting 4, when students are finalizing their team content assessment and preparing to begin the strategic roadmap report. A revised and expanded agenda for that meeting:

- Explain the organizational context of content creation: Who do you report to within the organization? What type of access do you have to users or customer data? What other units do you regularly interact with? What type of interactions?

- Discuss the business goals that relate to content creation: How is your unit’s success measured by the organization? How are individual content creators assessed? Is your unit’s success related to business goals or KPIs?

- Answer student questions based on their content assessment, as well as competitor and gap analysis activities.

- Prepare students to move from the audit findings to recommendations.

We have not seriously considered replacing the client-based project because students overwhelmingly want the opportunity to work with real content and the people who create and manage it in organizations. It may be possible to create a simulation that could capture that context; business school instructors appear to be successful at creating such pedagogical tools (e.g., Wharton Interactive at University of Pennsylvania, 2023). However, simulations are rare in technical communication, and publishing one would require determined faculty members with significant expertise and resources.

Challenge 2: Business complexity and instructor knowledge

Every organization represents a unique, complex system within which content is created (Bailie & Urbina, 2013). Complex systems have many dynamic variables that must be untangled to achieve insights because parts of the system display behaviors and characteristics that go beyond what the individual part does on its own (Project Management Institute, 2015). That complexity means even those with extensive business training and experience need help to determine which levers to pull to increase profits, hence, the global growth of the management consulting industry, whose market size in the U.S. was approximately 329 billion dollars in 2022 (Statista Research Department, 2023).

Business complexity means there is no simple solution for content strategy instructors to supplement their knowledge to teach students to be strategic about content by considering a client’s organizational system. We believe collaboration between educators and industry pros is the best option. Our own collaboration has been irreplaceable in the technical communication programs where we teach; it certainly prompted what we have learned and shared in this teaching case. There are others collaborating across the academic and industry split (Albers, 2016; Andersen & Evia, 2019; Evia, 2024). One specific way in which we will emphasize the importance of treating content as a business asset going forward is to add a content strategy consultant presentation meeting to the course schedule in Week 6, as students transition from team content assessment to individual strategic roadmaps in the client project. That virtual meeting will be recorded, so that it can be used by students who cannot attend the live session or who take the course later. In Week 7, we will also add a podcast focused on content strategy return on investment (Kinsey & Pringle, 2019).

Challenge 3: Content strategy and course packaging

We considered course delivery details as potential limitations on student learning. Given the specialized nature of graduate-level education, we think it is reasonable to expect students to engage deeply and effectively with the material and client project in our course within an eight-week period. Real-world parallels reinforce this view; customer analysis projects in professional settings often operate on similar, if not tighter, timeframes and involve a breadth of information gathering and analysis. However, the learning outcomes and project scope within this condensed course structure merit additional examination.

The content strategy course described in this paper purposefully limits itself to the three initial phases of content strategy: students begin in the discovery phase, move on to the gap analysis phase, and finally to the strategic roadmap phase (Bailie & Urbina, 2013). The phases that typically follow are identified for students but otherwise ignored. In industry, the content strategist would focus on the details of implementing the strategy and tactics, measuring their impact, and optimizing results (Nichols, 2015) typically included in ContentOps (Bailie, 2024).

In fact, the first phase (discovery) is key to identifying business problems related to content teams that should guide the development of strategic solutions. Rockley & Cooper (2012) devoted five chapters in their book on content strategy to determining business requirements; before they introduced the content audit as one aspect of discovery, they emphasized the importance of analyzing customer data, identifying business pain points, and understanding the content lifecycle, with its people and processes. This foundational discovery phase might merit a dedicated course to ensure students learn how to view the organizational context within which complex content issues arise.

Although segmenting the content strategy curriculum could provide a more focused and in-depth exploration of the typical strategy development phases, academic realities—staffing availability, faculty subject-matter expertise, availability of clients for projects—must also be considered. Yet, technical communication is known for its interdisciplinarity, and possible curriculum limitations could be addressed by partnering with other departments in other colleges. We suspect that students would be better prepared for an intensive, single eight-week course in content strategy if they had foundational business knowledge, such as financial literacy, organizational behavior, and marketing research. By leveraging the expertise available in business schools, our programs could offer a more thorough education that prepares students to navigate the complexities of content strategy within various organizational contexts. Although prerequisite courses can result in scheduling issues, this is an avenue we will consider going forward.

Conclusion

To summarize, we began by documenting the perceived lack of respect expressed by many technical communicators and by arguing that their overall lack of business understanding is a contributing factor and, more importantly, generates a leadership vacuum within the field. Because we believe building a better understanding of content as a business asset is a natural fit within content strategy coursework in technical communication degree programs, we described how we emphasize it in the course materials for students in our graduate programs. We then reported details for the six client projects completed by 45 students in our content strategy course between 2021–2023. The clients represented diverse organizations with a range of content types that were assessed by students. When interpreting the students’ final strategic roadmap reports for the project, we noted one major success: all students were able to identify issues with technical content quality and address them with appropriate tactics (e.g., adopting style guides, creating content models, etc.). Ultimately, we concluded that our goal of preparing technical communicators to be organizational content leaders was unmet. Despite emphasizing the connection between content and business value throughout the course, we found that most students struggled to explicitly link their content strategy recommendations to business outcomes in their final client project reports.

The most recommended strategies from students, quality assurance and information design, focused on increasing content quality. Another commonly recommended strategy, user focus, was rarely connected to business goals. Relatedly, the often-recommended tactic of user testing was treated as a means of implementing the information design strategy by increasing content quality. Another commonly selected tactic, a content planning calendar, was inappropriately discussed as a way to improve content quality by implementing the planning + estimating strategy, which instead focuses on budgets and schedules.

Only a handful of the 45 students explicitly and convincingly connected content issues with business causes or effects. One student recommended implementing user feedback to increase revenue through maintaining customers. A single student recommended the tactic of structured authoring but connected its adoption only to increased content consistency, with no mention of the efficiency inherent in content reuse and reduced business costs. One student recommended a content planning calendar to be strategic about planning + estimating, collaboration, and organizational structure. Of the students who recommended a strategy focused on organizational structure to address governance, only one connected their recommendation to the need for a content champion or leader.

To address some of these challenges, we propose enhancements, such as restructuring client interactions, collaborating with industry experts, refining project deliverables, and potentially integrating foundational business courses into the curriculum. One improvement we can make with little effort is to emphasize to students that the SWOT analysis required in their roadmap reports must focus on the organization (Puyt et al., 2023). The majority of students ignored the fact that their instructional materials explained and demonstrated SWOT as a technique for analyzing organizations. Instead, many attempted to apply SWOT to the content itself, which was universally unsuccessful and probably contributed to their lack of business focus in their strategic directions. In the future, we will make the focus explicit in the assignment instructions, but we will also ask students to submit a draft of their SWOT analysis in their status update due in Week 7. In that way, the instructor can intervene if needed before the student completes their roadmap report.

Future research might explore the effectiveness of these proposed solutions and identify additional strategies for developing technical communication students’ business acumen and strategic thinking skills in the context of content strategy coursework. Such research could provide valuable insights into bridging the gap between academia and industry practices.

Our experiences described in this case study certainly underscore the need for closer alignment between technical communication research and industry practices. As Friess and Boettger (2021) reported, there is a disparity between the scholarly focus on rhetorical aspects and practitioners’ emphasis on more tangible concerns. However, the trend toward process-oriented research suggests an opportunity for academics to contribute to the growing field of content strategy and address the leadership vacuum identified in our study. In the introduction to his Technical Communication special issue on improving research communication, Albers (2016) argued that technical communication had the opportunity to lead on the scholarship in information architecture; however, it ceded that work to library science, which now houses these academic programs. “The train for information architecture has left the station, and we’re still on the platform,” Albers wrote, “The train for content strategy is loading, and we don’t see too many academic researchers with tickets” (Albers, 2016, p. 296).

References

Abel, S. (2007). Most documentation managers don’t use metrics as performance measures. The Content Wrangler. https://www.brighttalk.com/webcast/9273/272013?utm_campaign=channel-feed&utm_source=brighttalk-portal&utm_medium=web

Albers, M. J. (2016). Improving research communication. Technical Communication, 63(4), 293–297.

Andersen, R., & Batova, T. (2015). The current state of component content management: An integrative literature review. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 58(3), 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2016.2516619

Andersen, R., & Evia, C. (2019). What leaders in industry and academia think about technical communication training and education. Proceedings of the 2019 STC Technical Communication Summit.

Bailie, R. (2020). Video interview on content strategy with Kim Sydow Campbell.

Bailie, R. (2024). Defining content operations. In C. Evia (Ed.), Content operations from start to scale: Perspectives from industry experts (pp. 13–24). Virginia Tech Publishing.

Bailie, R. A., & Urbina, N. (2013). Content strategy: Connecting the dots between business, brand and benefits. XML Press.

Batova, T. (2018). Work motivation in the rhetoric of component content management. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 32(3), 308–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651918762030

Bridgeford, T. (2020). Teaching content management in technical and professional communication. Routledge/ATTW Series in Technical and Professional Communication.

Campbell, J. L., & Katan, D. (2022). User-centered design (UCD) and transcreation of non-profit communications in a technical communication classroom. IEEE International Professional Communication Conference, 2022-July, 444–450. https://doi.org/10.1109/ProComm53155.2022.00087

Campbell, K. S., & Swisher, V. (2023). A maturity model for content strategy development and technical communicator leadership. Journal of Technical Writing & Communication, 53(4), 286–309.

Dayton, D., & Hopper, K. (2010). Single sourcing and content management: A survey of STC members. Technical Communication, 57(4), 375–397.

Dumlao, R. J. (2022). Collaborating successfully with community partners and clients in online service-learning classes. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472816221088349

Evia, C. (2024). Introduction. In C. Evia (Ed.), Content operations from start to scale: Perspectives from industry experts (pp. 1–12). Virginia Tech Publishing.

Evia, C. (Ed.). (2024). Content operations from start to scale: Perspectives from industry experts. In C. Evia (Ed.), Content operations from start to scale: Perspectives from industry experts. Virginia Tech Publishing. https://doi.org/10.21061/content_operations_evia

Flanagan, S., Getto, G., & Ruszkiewicz, S. (2022). What content strategists do and earn: Findings from an exploratory survey of content strategy professionals. Proceedings of the 40th ACM International Conference on Design of Communication (SIGDOC ’22), 15–23.

Friess, E., & Boettger, R. K. (2021). Identifying commonalities and divergences between technical communication scholarly and trade publications (1996–2017). Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 35(4), 407–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/10506519211021468

Gunning, S. K. (2014). Identifying how U.S. nonprofit organizations operate within the Information Process Maturity Model. SIGDOC 2014—Proceedings of the 32nd Annual International Conference on the Design of Communication. https://doi.org/10.1145/2666216.2666220

Hackos, J. T. (2007). Information development: Managing your documentation projects, portfolio, and people. Wiley.

Hackos, J. T. (2017). Information process maturity model. IEEE International Professional Communication Conference. https://doi.org/10.1109/IPCC.2017.8013946

Halvorson, K. (2020). Video interview on content strategy with Kim Sydow Campbell.

Hane, C., Lewis, D., & Marsh, H. (2019a). Association content strategies for a changing world.

Hane, C., Lewis, D., & Marsh, H. (2019b). Measuring and advancing your content strategy maturity. Intercom, March/April, 8–12.

Hart-Davidson, B. (2010). Content management: Beyond single-sourcing. In R. Spilka (Ed.), Digital literacy for technical communication: 21st century theory and practice (pp. 128–143). Routledge.

Howard, T. (2020). Teaching content strategy to graduate students with real clients. In G. Getto, J. Labriola, & S. Ruszkiewicz (Eds.), Content strategy in technical communication (pp. 119–153). Routledge/ATTW Series in Technical and Professional Communication.

Johnson, T. (2012). Technical communication metrics: What should you track? I’d Rather Be Writing. https://idratherbewriting.com/2012/03/02/technical-communication-metrics-what-should-you-track/

Johnson, T. (2023, October 6). What I learned in using AI for planning and prioritization: Content strategy might be safe from automation. I’d Rather Be Writing.

Jones, C. (2018). A content operations maturity model. GatherContent Blog.

Jones, C. (2019). The content advantage (Clout 2.0): The science of succeeding at digital business through effective content (2nd ed.). New Riders.

Kastman Breuch, L.-A. M. (2001). The overruled dust mite: Preparing technical communication students to interact with clients. Technical Communication Quarterly, 10(2), 193–210.

Kimme Hea, A. C., & Wendler Shah, R. (2016). Silent partners: Developing a critical understanding of community partners in technical communication service-learning pedagogies. Technical Communication Quarterly, 25(1), 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2016.1113727

Kinsey, G., & Pringle, A. (2019, July 29). Calculating return on investment for your content strategy. Content Strategy Experts Podcast from Scriptorium.

Kunz, L. (2015, September 4). Your guide to content strategy maturity models. Leading Technical Communication.

Layton, R. A., Loughry, M. L., Ohland, M. W., & Ricco, G. D. (2010). Design and validation of a web-based system for assigning members to teams using instructor-specified criteria. Advances in Engineering Education, 2(1), 1–28.

Lopes, L., & Godefroy, L. (2017). Raising awareness of the value of technical communication: Different contexts, but a common challenge. In Hypotheses. ComTech Universite de Paris. http://comtechp7.hypotheses.org/files/2017/10/Raising_TC_value_awareness.pdf

Ludwig, T. (2021a). Survey breakdown: 33% Of writers can’t report their own value—here’s how to start. Heretto Blog by Jorsek. https://heretto.com/survey-breakdown-33-of-writers-cant-report-their-own-value-heres-how-to-start/

Ludwig, T. (2021b). Survey breakdown: 72% of writers aren’t measured on specific content goals. Heretto Blog by Jorsek. https://heretto.com/writers-not-measured-on-specific-content-goals/

Molisani, J. (2021). Business skills for technical communicators. Intercom, November/December, 9–11.

Nichols, K. P. (2015). Enterprise content strategy: A project guide. XML Press.

O’Keefe, S., Pringle, A., & Swallow, B. (2019). Understanding content strategy as a specialized form of management consulting. Technical Communication, 66(2), 127–136.

Project Management Institute. (2015). Business analysis for practitioners: A practice guide. Project Management Institute.

Pullman, G., & Gu, B. (2007). Guest editors’ introduction: Rationalizing and rhetoricizing content management. Technical Communication Quarterly, 17(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572250701588558

Pullman, G., & Gu, B. (2020). Reconceptualizing technical communication pedagogy in the context of content management. In T. Bridgeford (Ed.), Teaching content management in technical and professional communication (pp. 19–39). Routledge/ATTW Series in Technical and Professional Communication.

Puyt, R. W., Lie, F. B., & Wilderom, C. P. M. (2023). The origins of SWOT analysis. Long Range Planning, 56(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2023.102304

Rockley, A., & Cooper, C. (2012). Managing enterprise content: A unified content strategy (2nd ed.). New Riders.

Rosende, S. M. (2016). Technical writing: The “Rodney Dangerfield” of career choices. LinkedIn Pulse. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/technical-writing-rodney-dangerfield-career-choices-susana-rosende-/

Rosselot-Merritt, J. (2020). Why are technical writers often treated as such an unimportant part of a company? I’d Rather Be Writing. https://idratherbewriting.com/blog/why-technical-writers-treated-as-unimportant/

Singer, W. (2001). What do technical writers find stressful? TechWhirl. https://techwhirl.com/what-do-technical-writers-find-stressful/

Spring, R., & Nesterenko, A. (2018). Liberal vs. professional advertising education: A national survey of practitioners. Journal of Professional Communication, 5(2), 15–40.

Statista Research Department. (2023, December 18). Consulting services industry worldwide: Statistics and facts. Statista.

Swisher, V. (2014). Global content strategy: A primer. XML Press.

Swisher, V., & Preciado, R. L. (2021). The personalization paradox: Why companies fail (and how to succeed) at delivering personalized experiences at scale. XML Press.

University of Pennsylvania. (2024, January 14). Wharton Interactive.

Walsh, I. (2010). How technical writers can move further up the food chain. Klariti Tips & Tools. https://www.klariti.com/technical-writing/2010/01/15/how-technical-writers-can-move-further-up-the-food-chain/

Willerton, R. (2013). Teaching white papers through client projects. Business Communication Quarterly, 76(1), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569912454713

About the Authors

Dr. Kim Sydow Campbell is Professor and Director of Corporate Relations in the Department of Technical Communication. She received her PhD in Rhetoric, Composition and Linguistics from LSU in 1990, and held positions at Auburn, the Air Force Institute of Technology, and the University of Alabama. She has published more than forty refereed papers and book chapters. Dr. Campbell was honored with the Jay R. Gould Award for Excellence in Teaching in 2022 from the Society for Technical Communication. She has also won honors as the Kitty O. Locker Outstanding Researcher Award from the Association for Business Communication, the Alfred N. Goldsmith Award for Outstanding Contributions to Engineering Communication and the Emily K. Schlesinger Award for Service from the IEEE Professional Communication Society. She served as Editor-in-Chief of the IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication from 1998 to 2008. She enjoys cooking, swimming, and playing with her dogs.

Dr. Ryan Boettger is Professor and Chair of the Department of Technical Communication at the University of North Texas. He received his PhD and MA in Technical Communication and Rhetoric from Texas Tech University. Dr. Boettger has published award-winning research in technical communication and writing studies journals. He is co-creator (with Stefanie Wulff, University of Florida) of The Technical Writing Project funded by the National Science Foundation. He is the former editor for the Wiley/IEEE Press book series in Professional Engineering Communication and the former deputy editor-in-chief for IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication. Dr. Boettger has over a decade of experience as a technical communicator, working as an editor for the Texas Army National Guard and as the Managing Director of Grant Proposal and Program Development for the Laura W. Bush Institute for Women’s Health. He enjoys TRX, running, hiking, cooking, and spending time with his family and friends.

Val Swisher is the Founder and CEO of Content Rules, Inc. Val enjoys helping companies solve complex content problems. She is a well-known expert in content strategy, structured authoring, global content, content development, and terminology management. Val believes content should be easy to read, cost-effective to create, and efficient to manage. Her customers include industry giants such as Google, Cisco, Visa, Meta, and Roche. Her latest book is The Personalization Paradox: Why Companies Fail (and How to Succeed) at Creating Personalized Experiences at Scale (XML Press, 2021). Val is on the Advisory Board for the Technical Communication Programs at the University of North Texas. When not working with customers or students, Val can be found sitting behind her sewing machine working on her latest quilt. She also makes a mean hummus.