Jackie Damrau, Editor

Books Reviewed in This Issue

The reviews provided here are those that are self-selected by the reviewers from a provided list of available titles over a specific date range. Want to become a book reviewer? Contact Dr. Jackie Damrau at jdamrau3@gmail.com for more information.

Every Brain Needs Music: The Neuroscience of Making and Listening to Music

Larry S. Sherman and Dennis Plies

Crisis Communication Strategies: Prepare, respond and recover effectively in unpredictable and urgent situations

Amanda Coleman

Interfaces and Us: User Experience Design and the Making of the Computable Subject

Zachary Kaiser

Composing Health Literacies: Perspectives and Resources for Undergraduate Writing Instruction

Michael J. Madson, ed.

Technical Writing for Dummies

Sheryl Lindsell-Roberts

The Language of Learning

Phylise Banner and Dawn J. Mahoney, eds.

Talking on Eggshells: Soft Skills for Hard Conversations

Sam Horn

Language, Society and Power: An Introduction

Annabelle Mooney and Betsy Evans

Content Audits and Inventories: A Handbook for Content Analysis

Paula Ladenburg Land

How to Talk Language Science with Everybody

Laura Wagner and Cecile McKee

Better Presentations: How to Present Like a Pro (Virtually or in Person)

Jacqueline Farrington

The Good Enough Job: Reclaiming Life from Work

Simone Stolzoff

The Long Journey of English: A Geographical History of the Language

Peter Trudgill

Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity Centered

Don Norman

Design for Learning: User Experience in Online Teaching and Learning

Jenae Cohn and Michael Greer

AI and Writing

Sidney I. Dobrin

The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is: A History, a Philosophy, a Warning

Justin E.H. Smith

The History of Color: A Universe of Chromatic Phenomena

Neil Parkinson

Making Sense of Mass Education

Gordon Tait, Nerida Spina, Jenna Gillett-swan, and Peter O’Brien

Every Brain Needs Music: The Neuroscience of Making and Listening to Music

Every Brain Needs Music: The Neuroscience of Making and Listening to Music

Larry S. Sherman and Dennis Plies. 2023. Columbia University Press. [ISBN 978-0-231-20910-6. 270 pages, including index. US 32.00 (hardcover).]

Every Brain Needs Music: The Neuroscience of Making and Listening to Music is the compilation of a musical neuroscience collaboration—a synopsis of what science knows and does not yet know about how making, practicing, performing, listening, and learning music affects the brain. And beyond that, how those effects spill over into the human experience.

The book’s layout attracts the musical reader with its orchestra labels. The introduction is a “Prelude” followed by an “Overture,” a short summary of the book. Each subsequent chapter is labeled with a numerical “movement.” Music lovers will delight at the final chapter, “Coda,” knowing that the coda of a song is a short ending following one or more repeated sections.

The first “movement” begins with a detailed description of basic neuroscience. This includes the most common method of studying the active mind—a procedure called functional magnetic resonance (fMRI). It is very similar to a regular MRI but specific for the brain; it “detects the changes in the flow of blood through tiny vessels in different regions of the brain and changes in blood oxygenation, which represent changes in neuronal activity” (p. 11).

Many of the preliminary results discussed are based on fMRI studies—flawed as it is as a measure of brain activity. One significant discovery with this technique is that music alone (not other sounds) triggers specific areas of the brain. This could redefine what music is from a neuroscience perspective. Also considered was a qualitative survey taken of professional musicians of all types with the results being compiled into general trends within bar graphs included in Appendix A.

The other “movements” (chapters of this book) on practicing, performing, and listening are most relevant to many readers while the “movements” on improvising and composing pertain to a smaller percentage of their audience. All chapters discuss specific studies related to a comparison of music type and how fMRI results (or similar PET scanning) differ and how those results might be interpreted.

All readers who have ever practiced and performed music at any level can relate with the statement, “Mastering a piece can be an ongoing process of unfolding its meaning, in terms of both personal expression and the composer’s intention. It’s a search. It’s never boring, but always challenging in positive ways, for music holds poetic space” (p. 70).

Overall, this collaborative book presents a thorough synopsis of current musical neuroscience research. Unfortunately, much of it is still in the infancy stage as current technology only allows us to surmise connections between brain parts. The specific mechanisms and interchanges beyond the basic neuron level are not yet understood on a chemical level.

In the “Coda,” Larry Sherman states, “I’m struck by the amount of computational power it takes to perceive and respond to music and the fact that we still have much to learn about the underlying circuitry involved in how sound is processed in the auditory cortex before traveling to other areas of the brain” (p. 198). This coda is perhaps the prelude to yet another set of movements to be written when this is discovered.

Julie Kinyoun

Julie Kinyoun is an on-call chemistry instructor at various community colleges in Southern California. An avid reader, she enjoys reviewing books that help her become a better educator.

Crisis Communication Strategies: Prepare, respond and recover effectively in unpredictable and urgent situations

Crisis Communication Strategies: Prepare, respond and recover effectively in unpredictable and urgent situations

Amanda Coleman. 2023. 2nd ed. KoganPage. [ISBN 978-1-3986-0941-9. 230 pages, including index. US$34.99 (softcover).]

Crises, by definition, happen without warning. Communicators must therefore respond without the luxury of enough time to consider their responses. In the second edition of Crisis Communication Strategies: Prepare, respond and recover effectively in unpredictable and urgent situations, Amanda Coleman provides the tools you’ll need to plan for and successfully respond to crises. The book’s packed with strategies for developing and implementing communication plans that work. The key? Coleman repeatedly emphasizes the importance of understanding stakeholder needs by means of audience analysis, of developing stakeholder-specific plans, of planning and testing to confirm the plans work, and of frequently reviewing plans to account for changes in an organization’s operating context. Most technical communicators assume that communication is emotionally neutral, with clarity and concision—skills we need to learn and use even outside a crisis—more important than any emotional context. Coleman sets her book apart from most communication books you’ve read by repeatedly emphasizing the audience’s physical and emotional needs. Crises are emotionally and physically exhausting, both inside the organization and out. Communication can’t succeed without mitigating these problems by first gaining the audience’s trust through judiciously chosen words accompanied by actions consistent with the words.

Crisis communicators must continuously acknowledge the audience’s feelings and fears to provide reassurance. They must listen to and respect the audience’s emotional responses. Unlike most technical communication, crisis communication can’t be one-way; it must change from dictation to dialogue. Many organizations think that online discussion forums can replace personalized support from organization representatives. During a crisis, they can’t.

The best-laid plans fail when they become dusty binders, ignored on someone’s shelf. Instead, they must become living parts of the organization’s daily processes so that everyone understands their role in a crisis and can immediately act or support the actions of others. Many scrupulous response plans were prepared after the SARS and MERS pandemics; people died during the Covid-19 pandemic because few of these plans were followed. They’d been forgotten.

There are, inevitably, omissions and oddities: Coleman doesn’t start by defining “crisis” and listing typical crisis types, from physical (explosions) to “soft” (stolen confidential data), which remain implicit until later in the book. This makes it difficult for readers to build their own list of scenarios they must plan for. Adding a chapter on vulnerability analysis would solve this problem. Although Coleman mentions the importance of decision-support tools (checklists, flowcharts) and of support, the book has no Web page that links to key traditional and new social media, including discussion forums and groups of communication colleagues, nor links to important tools such as sample plans, downloadable templates, and software links (reputation monitors).

Criticisms notwithstanding, Crisis Communication Strategies is a great introductory textbook, and even non-crisis communicators will learn much from this book.

Geoff Hart

Geoff Hart is an STC Fellow with more than 35 years of writing, editing, and translation experience. He’s the author of two popular books, Effective Onscreen Editing and Write Faster With Your Word Processor.

Interfaces and Us: User Experience Design and the Making of the Computable Subject

Interfaces and Us: User Experience Design and the Making of the Computable Subject

Zachary Kaiser. 2023. Bloomsbury Visual Arts. [ISBN 978-1-3502-4524-2. 224 pages, including index. US$29.95 (softcover).]

In Interfaces and Us: User Experience Design and the Making of the Computable Subject, Zachary Kaiser draws the dotted line from the established frameworks of physical design assets, like posters, to define what he calls “computable subjectivity” as it relates to user experience design (UXD) to create interfaces. These interfaces are part of the slow, methodical conversion of people into information processors to be classified only as the data they provide as computable subjects. After the foundational research tying the book’s concepts to Foucault’s theories of “biopolitics” and “biopower” that shape algorithmic classification powering predictive technology, Kaiser informs readers this makes it possible for UXD to infer and create restrictions that “guide” user interaction with every interface.

After Kaiser shares the main underpinnings and recognized influences for his findings, he walks through the impact of people being reduced to the information processes that can be derived from knowing nuanced and nano-specific data points about their behavior. He explores the moral, emotional, and resulting political probabilities from normalizing the reduction of people to computational subjects that he believes will lead to UXD being used to create future behaviors. Technological advances like the inclusion and normalization of statistical analysis for optimization as far back as 1940 are referenced to show readers how long corporations have planned to introduce and normalize cybernetics, so that the data derived from people would create people’s reality.

A case is made about the negative consequences of “Neoliberal Healthcare” executed through wearable technology like the Amazon Halo. Kaiser argues this technology and the response to the ability to optimize oneself will lead to negative consequences like anxiety because of the moral dilemma people will feel for “not optimizing” one’s health. He also states this will lead to superfluous (a crasser word was used) jobs, superfluous people, and moral degradation for those who “buy-in” to the datafication of their health.

If viewing human computer interaction through the lens provided by Kaiser, contributors to data driven products—including those tasked with UXD—will create a damaging future where every interface becomes an instrument of control disguised as a tool for interaction. Each person contributing to the creation of interactive products is playing a part in supporting an economic outcome like what led to “Chile Socialist Cybernetics” that were lauded as helpful but responsible for more harm than good. Kaiser proposes instead of aiding well-meaning or ill-informed corporations that further the “propagation of computable subjectivity” UX designers should engage in “Luddite” (UX) Design Education that should be taught as a form of resistance that will slow down or stop the ability to produce “the fictions that begin in the minds of tech company CEOs and founders” (p. 136).

Shawneda Crout

Shawneda Crout works as a technical project manager and an author. When she isn’t working on a project, solve, system, or process, you’ll find her working on her next book. Learn more at shawneda.com.

Composing Health Literacies: Perspectives and Resources for Undergraduate Writing Instruction

Composing Health Literacies: Perspectives and Resources for Undergraduate Writing Instruction

Michael J. Madson, ed. Routledge. [ISBN 978-1-03-229926-6. 236 pages, including index. US$44.95 (softcover).]

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the public’s lack of health literacy worldwide, and governments and universities are taking notice. Poor health literacy is associated with higher rates of hospitalization and premature death as well as “risky behaviors, ill health, and mismanagement of chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, and asthma” (p. 1). The question is, who should teach students health literacy and how should we teach it? Composing Health Literacies: Perspectives and Resources for Undergraduate Writing Instruction, edited by Michael J. Madson, seeks to answer those pressing questions by suggesting ways in which higher education might place health literacy instruction in undergraduate writing instruction (UWIs) programs.

Composing Health Literacies is divided into three main parts, each addressing a different component of teaching health literacy in a UWI context. Part 1 addresses assignments and courses, Part 2 profiles programs that have successfully integrated health literacy instruction into their UWI programs, and Part 3 discusses rhetorical and contextual studies that may further illustrate how health literacy can be woven into a UWI curriculum.

Madison’s edited collection is valuable because it approaches the subject from many different perspectives. Although all the contributors, except one, are employed at universities within the United States, the authors look at UWI and health literacies from a variety of perspectives, ranging from medical programs to English and rhetoric programs, to public health programs. Exploring these varying perspectives is valuable for technical writing instructors housed in English and other non-medical departments at universities because it lets us survey ways in which medical professionals integrate their subject matter into their undergraduate writing courses.

According to Madson, the audience for Composing Health Literacies includes instructors of health career-focused undergraduate education as well as other instructors involved with undergraduate writing unrelated to medicine who wish to include health literacy topics within their classroom (pp. 8-9). As a Professor of English who teaches medical rhetoric along with technical writing, I could envision including some of these assignments and health literacy topics in my courses. The inclusion of these topics into first-year composition courses may be a harder sell, however, as many of these programs have greater limitations on the topics and genres they can teach. Further, the political climate of some areas within the United States may make addressing health literacy in writing classrooms risky for instructors.

Despite some of the limitations of the text, Composing Health Literacies would be a useful addition for the library of any instructor of undergraduate writing. This text presents a fresh take on writing instruction for technical writing instructors who have some flexibility within their curriculums.

Nicole St. Germaine

Nicole St. Germaine is a Professor of English and the Coordinator of the Technical and Business Writing Program at the Natalie Z. Ryan Department of English at Angelo State University.

Technical Writing for Dummies

Technical Writing for Dummies

Sheryl Lindsell-Roberts. 2023. 2nd ed. Wiley Publishing, Inc. [ISBN 978-1-394-17675-5. 384 pages, including index. US$29.99 (softcover).]

If you have seen any of the For Dummies books, then you should know what to expect from this one. They all follow a tried-and-true template and are aimed at new learners, people who are curious about a subject, but who feel a little stupid in the face of what they don’t know. They serve this audience well. The writing is chipper and reassuring, and they do a good job of quickly familiarizing the reader with the essential elements of their subject.

While basic in its coverage, even experienced technical writers may want to have a look at the second edition of Technical Writing for Dummies. Technical communication is a broad, complex, and quickly evolving field. No matter how experienced you are, there are areas you have not experienced but should know about. Much has changed since this book’s first edition appeared 20 years ago, and it does its best to cover emerging technologies and methods of working.

Those interested in breaking in will appreciate the book’s summary of the skills and qualities you need to succeed, and its advice on creating portfolios, a LinkedIn profile, and so on.

Throughout the advice is good, if basic. It emphasizes the importance of planning and offers a useful model template for a technical writing brief, a variety of documentation plan in which you gather and record information about document type, presentation context, audience profile, schedule, resources, team, and so on. You can download a ready-to-be-filled-in version of the writing brief from the Dummies website.

Sheryl Lindsell-Roberts covers the subject’s basics—focus on user needs, strive for clarity and consistency, use the active voice, chunk information, follow conventions for handling types of lists, and so on. Her book also offers basic advice for producing a variety of frequently written documents—user manuals, abstracts, specification sheets, and executive summaries.

Technical communication often requires research, so the book covers designing questionnaires and surveys, and the ins and outs of finding answers online.

Not all technical communication results in a written document, so Lindsell-Roberts covers topics such as giving presentations, and such new technologies as e-learning and gamification.

Turning to the working environment, the book discusses working collaboratively, building trust, giving constructive feedback, team etiquette, and tools, such as those used for videoconferencing.

Technical Writing for Dummies rounds things out with a host of ancillary subjects including protecting intellectual property, advice for writing white papers, and publishing in professional journals.

No profession is without its downsides, so Lindsell-Roberts wraps up her book with common frustrations you may encounter—work overload and time pressure, problems with subject matter experts, poorly defined and managed projects, and others.

A series of appendices reviews punctuations and grammar and defines common abbreviations and technical terms.

While it will not replace experience or formal training, if you are curious about the technical writing profession, need a good overview of the challenges you might face, and wonder whether you might be a good fit, Technical Writing for Dummies will serve.

Patrick Lufkin

Patrick Lufkin is an STC Fellow with experience in computer documentation, newsletter production, and public relations. He reads widely in science, history, and current affairs, as well as on writing and editing. He chairs the Gordon Scholarship for technical communication and co-chairs the Northern California technical communication competition.

The Language of Learning

The Language of Learning

Phylise Banner and Dawn J. Mahoney, eds. 2023. XML Press. [ISBN-978-1-937434-84-7. 166 pages, including index. US$25.95 (softcover).]

The Language of Learning is a handy reference book compiled by Phylise Banner and Dawn J. Mahoney providing 52 words and phrases used in the learning industry from 52 instructional design and learning practitioners. Many of the authors may be familiar to the readers as they have been participants in various STC activities.

The structure of The Language of Learning reminds me of a set of building blocks. There are five main sections: Design, Strategy, Implementation, Evaluation, and Innovation. By grouping related words and phrases this way, a flow builds from one term to the next. Each author’s definition answers the same set of questions: What is it? Why is it important? Why does a business professional need to know this?

There is care and thought behind this, where the divisions, the questions, and the discussions build on one another. This is not a dry presentation of definitions, but a fuller discussion that may spark additional research. Information is presented conversationally, enabling readers to link what they already know to what they are learning. The explanations are accessible, in plain language and immediately useful. The definition shows how a word or phrase is related to creating effective learning programs. Additional resources include a glossary of additional terms, a references section, a contributor index, and a subject index.

I found the References section facilitated an impulse to dive more deeply into a particular topic by using the links to the source material. The Language of Learning is a book that will spark a desire to learn more about a word or phrase but will provide sufficient information to understand the word or phrase. It may not be a book to just sit down and read cover to cover, but it is a delight to assess one’s understanding of a word or phrase. Checking a definition can morph into an invitation to explore further through the business professional section and the wealth of references. Each definition includes a short professional biography of the author and their contact information.

Who can benefit by adding The Language of Learning their resources shelf? Everyone engaged in constructing any kind of learning communication. Students may find it easier to find a quick answer here than in a textbook. It will be especially useful to those technical communicators who have decided to transition into instructional design, as well as those technical communicators whose job duties have been expanded to include providing instructional design content.

Marcia Shannon

Marcia Shannon, CPTC, is an STC member in the Carolina Chapter and IDL SIG. With more than 30 years in IT, finance, and insurance, Marcia has written procedures and job aids, trained co-workers and customers, and provided user support. Although retired, she is looking for more adventures in technical communications.

Talking on Eggshells: Soft Skills for Hard Conversations

Talking on Eggshells: Soft Skills for Hard Conversations

Sam Horn. 2023. New World Library. [ISBN 978-1-60868-849-4. 348 pages, including index. USD$19.95 (softcover).]

Improving communications in an organization, office, school, or home would for sure be an admirable goal, and Talking on Eggshells: Soft Skills for Hard Conversations makes an admirable attempt to help people achieve this goal. Anyone trying to improve communications in any setting will benefit from reading Sam Horn’s book. This can include in a situation, for example, where you have communication issues anywhere from a toxic work environment to a school or family issue.

Horn’s background is indeed impressive as she tackles a wide array of topics as someone ignoring rules or boundaries (p. 197), someone being manipulative (p. 255), and “someone is making my life miserable” (p. 184).

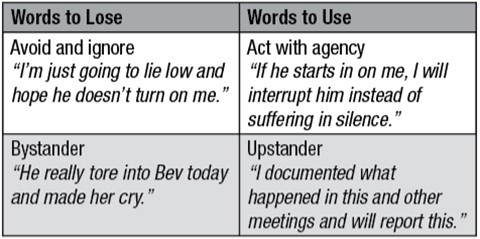

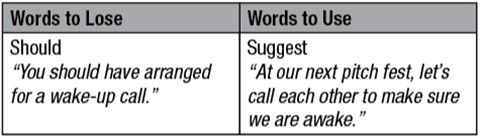

The author tackles the topic of dealing with a bully providing in part the following advice besides recommending that you document an incident (p. 283).

If a co-worker overslept and missed an important presentation you had to consequently make alone, consider the following (p. 94) as explained by Horn.

Horn’s advice makes me think she is like a friend who is also a professional who can provide some most welcome, useful advice. This can be especially helpful to someone who tends, as I do, to avoid confrontations when it would do me better to address an issue and solve a problem ideally as Horn shows with kindness.

Jeanette Evans

Jeanette Evans is an STC Associate Fellow; active in the Ohio STC community, currently serving on the newsletter committee; and co-author of an Intercom column on emerging technologies in education. She holds an MS in technical communication management from Mercer University and undergraduate degree in education.

Language, Society and Power: An Introduction

Language, Society and Power: An Introduction

Annabelle Mooney and Betsy Evans. 2023. 6th ed. Routledge. [ISBN 978-0-367-63844-3. 286 pages, including index. US$38.95 (softcover)].

Language, Society and Power: An Introduction provides a critical examination of sociolinguistics with contemporary topics and examples. The book is clearly a textbook, so readers should be aware of the deep dive that each chapter takes into linguistic matters. Teachers in disciplines other than linguistics, such as technical and professional writing, might find the text relevant in a variety of classes because of the comprehensive coverage on complex and critical issues regarding language and language use.

Ten of the eleven chapters take readers from the basics of linguistics, such as discussing what language is and what it represents, to more timely subjects of language and politics, media, gender, ethnicity, and age. There are also chapters on linguistic landscapes, how language is linked to class and symbolic capital, and global Englishes.

The chapters are consistent and well organized. They begin with an introduction and thorough definition of the chapter’s subject (what is gender, for instance), and then moves on to more complicated issues related to the subject, with technical words bolded and well defined. There are activity boxes in each chapter, which I considered to be one of the strong points of this book because the activities are usually on modern issues or perspectives and challenge readers to use chapter material and think critically. They would serve well as starters for class discussions. For instance, in “Language and Ethnicity,” readers are asked to define their own ethnicity and distinguish between their ethnicity and that of other people, meaning they must engage in thinking about the characteristics they use to define themselves and compare them to the characteristics they use to define others. This activity is a precursor to further coverage on racism, reclaiming terms, language variation, and ethnicity and identity, all material that people see and hear about in mainstream news and present-day social conversations.

Another strength of the book is the presentation of critical perspectives on each subject. Readers are presented with several perspectives or theories on a subject, and Annabelle Mooney and Betsy Evans critically examine each one for issues of equality, equity, inclusion, and humane, respectful treatment for everyone. They clearly show the connection between language and how it can be used to create uneven power that benefits some and marginalizes others, and how simple modifications could reposition that power and create a balance. For example, in “Language and Gender,” discussion on marked and unmarked terms show how marked terms, such as women’s titles (Miss, Mrs., and Ms.) always reveal information about her that the unmarked term, Mr., does not reveal about men. Or how the ‘cis’ in cisgender is one way to unmark the presently marked term transgender. And the last chapter, “Projects,” is incredibly helpful for greater engagement through project descriptions that promote engagement and critical thinking for each chapter.

Language, Society and Power addresses incredibly important and timely issues regarding the influence of language in a world that is struggling to understand how language functions in society.

Diane Martinez

Diane Martinez is an STC member and an associate professor of English at Western Carolina University where she teaches technical and professional writing. She previously worked as a technical writer in engineering, an online writing instructor, and an online writing center specialist.

Content Audits and Inventories: A Handbook for Content Analysis

Content Audits and Inventories: A Handbook for Content Analysis

Paula Ladenburg Land. 2023. 2nd ed. XML Press. [ISBN 978-1-937434-82-3. 252 pages, including index. USD$29.95 (softcover).]

Paula Ladenburg Land begins her book with the sentence: “Audits are all around us” (p. xiii). In the second edition of Content Audits and Inventories: A Handbook for Content Analysis, created in the wake of new developments in technical communication—such as UX writing, the increasing prevalence of structured authoring, and new software tools that can supposedly assess content for you—Land reaffirms the importance of content auditing as a method for evaluating content against business and user goals. She reminds us that, “Content inventories and audits provide a valuable window into the current state of your organization’s content” (p. 27).

Land is also careful to distinguish between a content inventory and a content audit, a common confusion among professionals who are new to content strategy. A content inventory is the process of “creating an organized listing of content assets” (p. xvi), whereas a content audit is a “qualitative evaluation of content against a set of defined criteria” (p. xvii). A content inventory gives you the foundation for assessing content, but you must go further and rigorously assess content through a full audit if you want to determine “whether the content supports business and user goals” (p. xviii).

The main bulk of Content Audits and Inventories is devoted to the process of conducting a content audit, with accessible section titles such as “Planning Your Audit Project” (p. 1), “Building the Audit” (p. 37), and “Conducting the Audit” (p. 97). Each chapter within these sections is grounded in examples of actual practices, such as in Chapter 8: Selecting and Defining Audit Criteria where Land presents a sample rubric for auditing content for audience sensitivity and usability/readability (p. 73). The chapters are short, to-the-point breakdowns of each content auditing step, which is admittedly a complex process.

Sprinkled throughout the book are also helpful callout sections such as “What if I Missed a Criterion” that attempt to troubleshoot common issues with auditing (p. 62). In addition, a series of appendices provide a wealth of resources for auditing, including Appendix A: Sample Content Inventory (p. 190), Appendix B: Stakeholder Interview Template (p. 191), and Appendix C: Content Audit Checklist (p. 195). In a relatively compact volume, there is little this reviewer, himself a content auditing expert, can imagine adding. Content Audits and Inventories quite simply provides everything one needs to know to conduct effective, efficient content audits.

And anyone who has delved deeply into content strategy readings can immediately grasp the value of such a book. There is no more complete source on content auditing anywhere in existence. Every book on content strategy mentions the broad strokes of content auditing and its importance, but none have devoted more than a chapter to explaining how to perform an audit. Readers will find within the pages of Content Audits and Inventories not only important considerations for understanding the goals and methods of content auditing, but also practical, hands-on advice for performing them.

Guiseppe Getto

Guiseppe Getto is a faculty member at Mercer University. He is also Director of Mercer’s M.S. in Technical Communication Management.

How to Talk Language Science with Everybody

How to Talk Language Science with Everybody

Laura Wagner and Cecile McKee. 2023. Cambridge University Press. [ISBN 978-1-108-79492-3. 268 pages, including index. US$34.99 (softcover).]

Language is full of amazing phenomena, and language scientists can lead others to “Aha!” moments by revealing little-considered aspects of the language people use every day. The question is “How?” The answer: “doable demos,” self-contained language-science activities to use in informal settings like festivals, libraries, and museums—places where people go to have fun and learn. In How to Talk Language Science with Everybody, Laura Wagner and Cecile McKee provide a step-by-step plan to develop your own doable demo.

The authors caution readers to ditch the school mindset. In free-choice settings, no one is required to attend, or even pay attention. It’s up to you to generate excitement and hold people’s interest. The adage “Get ‘em in the booth” applies, and the authors suggest pitches to attract passersby, like “Do you want to trick your brain?” or “Get your free spectrogram here!”

Wagner and McKee do a stellar job of putting the “everybody” in How to Talk Language Science with Everybody, describing scaffolding techniques to reach an audience with wide-ranging experiences and ages, from toddlers to adolescents to adults. The activities described take advantage of natural curiosity and are “doable” with few outside resources. Attention-getting giveaways like a spectrogram printout (p. 85), a headband with a picture of a brain (p. 47), and name tags written in the international phonetic alphabet (p. 134) add to the enjoyment.

This how-to guidebook is geared specifically to language scientists—linguists, psychologists, speech pathologists, audiologists, computer scientists, anthropologists, and the like—but the core lessons apply to any science communication. The book contains 20 well-organized chapters that emphasize different components of “how to talk language science,” with engagement techniques based on Paul Grice’s Conversational Maxims and adherence to the known-new contract, that is, finding common ground with your audience before imparting new information.

Every chapter has an Opening and Closing Worksheet with guiding questions to help you produce a doable demo. However, I found the worksheets less helpful than other regular chapter components, especially the Worked Example Box, which gets into the nitty-gritty of sample demos in many subdisciplines of linguistics, and the informative Further Reading section.

The authors promise practical advice and certainly deliver, with specifics that make the book shine. Wagner and McKee offer tips for finding and working in various venues. They cover must-know considerations that many learn only by trial-and-error, such as bringing a tablecloth to store equipment out of sight; labeling cords, boxes, and electronics; and having extras like tape, markers, pens, chargers, etc. The list is extensive.

The authors’ tone is open and friendly but not cloying. One of the goals of the doable demo is to show that science learning can be fun and can happen anywhere. Communicating language science is ripe for “Aha!” moments, and How to Talk Language Science with Everybody helps you to help others have their own “Aha!” moment.

Bonnie Denmark

Bonnie Denmark is an STC Member and Coordinator of the Business and Technical Writing Option at Western Connecticut State University. She was previously a software developer, focusing on natural language applications and human factors.

Better Presentations: How to Present Like a Pro (Virtually or in Person)

Better Presentations: How to Present Like a Pro (Virtually or in Person)

Jacqueline Farrington. 2022. Ideapress Publishing. [ISBN 978-1-64687-046-2. 198 pages, including index. US$19.95 (softcover).]

Better Presentations: How to Present Like a Pro (Virtually or in Person) is part of the “Non-Obvious Guides” series which “focus on sharing advice that you haven’t heard before” (Publisher’s Note page). However, while readers with presentation experience will likely gain a few new techniques they will already be acquainted with much of the book’s content.

This is not a critique of Jacqueline Farrington’s experience and expertise regarding the topic. Farrington draws upon her acting and former Yale Drama School faculty member experience “…to help clients create presentational performances that are more dynamic, engaging, human, and authentic” (p. iii). Her advice also covers virtual presentations, which have become a common presentation format.

Better Presentations is intended to be a guide. It is written succinctly with practical tips and brief “Story” sections that clarify the topics with Farrington’s personal experiences and anecdotes from sports, acting, and other fields. The book’s format, with bulleted lists and appropriate use of color and formatting making section topics and key points easily identifiable and facilitates its use as a guidebook.

Farrington mentions that the guidebook provides an online resources component for more in-depth information to the topics she introduces and directs readers to the online appropriate resources throughout the book. For example, in Chapter 5, “Voice”, the book instructs readers to “Visit Online Resources for: A listening guide to audit and improve your voice” (p. 62).

Unfortunately, when I tried to access the online resources component (www.nonobvious.com/guides/betterpresentations), it was not available at the time of the review. I looked forward to reviewing these resources as I was interested in learning more about the topics that Farrington introduced in the book. I found the “Coming Soon!” explanation on the website disappointing as a reviewer and a disservice to readers who purchase the book. Readers should have access to the entire content.

Because the online component is an integral part of Better Presentations, I cannot recommend this book as I was unable to review the entire guidebook.

Ann Marie Queeney

Ann Marie Queeney is an STC senior member with more than 20 years’ technical communication experience primarily in the medical device industry. Her STC experience includes serving as a Special Interest Group leader, 2020-2022 Board member, and CAC (Communities Affairs Committee) Chair. Ann Marie is the owner of A.M. Queeney, LLC.

The Good Enough Job: Reclaiming Life from Work

The Good Enough Job: Reclaiming Life from Work

Simone Stolzoff. 2023. Penguin Random House. [ISBN 978-0-593-53896-8. 240 pages, including notes. US$28.00 (hardcover).]

Simone Stolzoff examines the culture of workism in The Good Enough Job: Reclaiming Like from Work. Through stories of workers, Stolzoff examines common myths such as “this company is like a family” and “do what you love and never work a day in your life” (p. xxiv) According to Stolzoff, these stories “live in the tension between seeing work as a means to an end and seeing work as the end itself” (pp. xxiv–xxv).

As I read this book, I found it incredibly easy to relate to each person in these stories. They are driven, ambitious, and passionate but also burned out, disenchanted, and exhausted. And, just like me, their identity and their work were linked. Take Divya Singh, for example, who spent seven years nurturing the idea of a dairy-free product line into the successful company, Prameer. When she finally left, she said there was a “gaping hole in [her] identity” (p. 9).

The highlight of these stories, though, is that each person developed a strong sense of who they were when they weren’t working, which resulted in a healthier relationship to their work. For Divya, she says, “I know my price…Because I developed my identity outside of work, there’s a cost that if work cuts into it—if it ever costs me a larger part of my identity and my life—I know it’s not worth it” (p. 18).

For many of us who live in a culture of workism, it’s not easy to develop a sense of self that is separate from our work. We wrestle with it “every time we decide whether to spend an extra hour at the office or to check our email on a Sunday” (p. xxv). The boundary between work and life is so easily blurred if we let it. Stolzoff even shares his own struggles: “The truth is, I’m embarrassed by how my sense of self-worth is tethered to my productivity. Despite writing a book about right-sizing work’s place in our lives, I’d be lying if I told you I’d found an easy way to do so myself” (pp. 179–180).

While Stolzoff doesn’t provide any quick fixes to separate your self-worth from your work, he does share the experiences of those who have struggled to develop healthier relationships with work. Their stories prompt readers—like me—to examine their own relationship to work. I highly recommend The Good Enough Job to people who live and work in a work-centric society.

Sara Buchanan

Sara Buchanan works at London Computer Systems, a property management software company, in Cincinnati, OH. In her free time, she’s an avid reader, enjoys cooking, and doting on her cats: Buffy and Spike.

The Long Journey of English: A Geographical History of the Language

The Long Journey of English: A Geographical History of the Language

Peter Trudgill. 2023. Cambridge University Press. [ISBN 978-1-108-94957-6. 192 pages, including index. US$24.99 (softcover).]

Linguists typically study language genealogically, by showing how one language descends from a previous one. Genealogy, however, is also geography: linguistic relationships, and therefore genealogical linkages, are determined by languages “travelling from one place to another” (p. 1). The history of English is a record of its 5000-year journey “chronologically and spatially…from the heart of the Eurasian landmass…to the furthest ends of the earth” (p. 1).

The journey to modern English begins in Central Asia around 4000 BC when the Indo-European language “underwent geographical expansion” that resulted in different dialects and “eventually, different languages, of which Germanic was one” (p. 4). As Germanic spread into southern Scandinavia, Northern Germany, and the North Sea Coast, it split into early versions of German, Dutch, Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, Icelandic, Frisian, and English—each language distinguished linguistically through geographical difference.

The Germanic geographic movement collided with the Proto-Celtic languages then dominant in Europe, beginning the “3000-year long retreat by Celtic” (p. 18). The diminution of Celtic was accelerated by the rise of Anglo-Saxon in Britain around AD 450. Hired as mercenaries by Romanized Britons, the Anglo-Saxons eventually revolted, gaining “control of most of England” and achieving “gradual domination” of the Celts (p. 37), who were driven to the periphery of Britain, with only Welsh, Cornish, Cumbric, and Gaelic enclaves remaining. Speakers of Breton fled to northern France (the future Normandy), so that by AD 600 Welsh, Cornish, and Breton had essentially been replaced by Anglo-Saxon. By AD 900, the displacement of Britons by Anglo-Saxons was such that they “gave their name to the whole of England—as well as the language” (p. 46).

The largest expansion of English, however, occurred with overseas colonization, especially in North America, as the English took lands “from native peoples” and earlier settlers like the French. Three factors enabled the expansion: English speakers arriving in America; extermination or expulsion of indigenous people; and “language shift” or gradual absorption of English by native populations (p. 76–77). The acquisition of French lands after the French and Indian War in 1763, the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the defeat of Mexico by Texas, and California statehood accelerated the spread of English throughout the United States and Canada. The rise of Indian Boarding Schools similarly compelled indigenous children to speak English and adopt European culture.

Within a hundred years, English had expanded from the “eastern seaboard of North America” (p. 114) to areas as remote as Australia and New Zealand, where imposition of English destroyed “aboriginal cultures and languages” (p.127); and India, where English became an official lingua franca or “second language” (p. 164) enabling common governance of different linguistic minorities.

Will English remain the world’s dominant language? As Peter Trudgill shows, any language can decompose into different dialects and languages. Modern English is no different. Only time and geographical change will tell.

Donald R. Riccomini

Donald R. Riccomini is an STC member and Emeritus Senior Lecturer in English at Santa Clara University, where he specialized in engineering and technical communications. He previously spent twenty-three years in high technology as a technical writer, engineer, and manager in semiconductors, instrumentation, and server development.

Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity Centered

Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity Centered

Don Norman. 2023. The MIT Press. [ISBN 978-0-2620-4795-1. 376 pages, including index. US$29.95 (hardcover).]

Can design create a better world? What is the role of the designer in creating this better future? Is success even possible, or is it already too late? Don Norman explores the answers to these questions in his latest book, Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity Centered. He argues that design is at the center of the climate crisis, and that just about everything that exists in the world today is designed. In his arguments about design’s role in creating the climate crisis, Norman reminds us that Victor Papanek, a very influential, controversial designer and design critic, once said, “There are professions more harmful than design, but only a very few of them” (p. 21). Design for a Better World considers designs’ role in causing, as well as solving, the climate crisis.

This book presents and argues for a humanity-centered approach to design, rather than human-centered design. Human-centered design has been the battle cry for several decades in design. Norman argues that human-centered design tends to focus on individual needs, and to solve the climate crisis, or at least to reduce the symptoms, we need to focus our efforts on more than just individual needs. Instead, a humanity-centered approach to design considers humanity as a whole, it addresses the entire ecosystem, and the environment as well as all living creatures.

Throughout the book, the tone is balanced on the edge of a knife, wavering between somewhere just on the verge of alarmist, to hopeful for a better future. However, it never crosses over into full-on alarmism, likely because Norman understands that if he goes that route, he will lose most of his readers, who will give up because they will perceive that the situation is already hopeless. Thankfully, this is not the story he presents. Design for a Better World contains many ideas for design reform, education reform, and business reform, but Norman argues that small steps are more manageable in the form of modular. Additionally, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, and instead he argues that a modular approach is the key. Design is at the heart of the solutions Norman presents, but he also argues that designers can’t solve these problems alone, and the designers need to work with stakeholders in addressing problems at a modular level.

Don Norman is a designer, researcher, and engineer specializing not only in design but also in psychology. Like his other books, the writing in Design for a Better World is very accessible and largely targeted at practicing designers. Anyone interested in design and climate change reform would learn much from this book. Norman’s book should be required reading for everyone because, as he reminds us, “Everyone is a designer” (p. 188).

Amanda Horton

Amanda Horton holds an MFA in Design and teaches graduate and undergraduate courses at the University of Central Oklahoma (UCO) in design history, theory, and criticism. She is also the director of the Design History Minor at UCO.

Design for Learning: User Experience in Online Teaching and Learning

Design for Learning: User Experience in Online Teaching and Learning

Jenae Cohn and Michael Greer. 2023. Rosenfeld Media. [ISBN 978-1-959029-16-8. 198 pages, including index. US$49.99 (softcover).]

Those of us who teach or train online and are interested in user experience (UX) design and instructional design have been waiting for a book like Design for Learning: User Experience in Online Teaching and Learning for many years. As Jenae Cohn and Michael Greer claim in their opening chapter, “Learners are not sponges who absorb information through osmosis. But many learning platforms are unconsciously based on a model that defines learning as information transfer” (p. 8). In place of this paradigm, they suggest a move toward learning experience design, a blend of UX and instructional design that “defines learning as an active and interactive process” (p. 9). Rather than focusing on the “content” of learning, the learning experience designer model “encourages designers to focus on what the learners are doing—or how they are using the content and why” (p. 10).

The rest of the book proceeds to lay out how to design learning spaces that are interactive and assume an active learner. This includes processes such as Learning about Your Learners (Chapter 2), Setting the Foundation (Chapter 3), and Building a Space for Online Learning (Chapter 4). The book also includes chapters that focus on particular modes of learning, such as Producing Videos (Chapter 7), and Facilitating Live Webinar Presentations (Chapter 8). Finally, the book describes how to increase interaction in online learning with chapters like Building Connections Among Learners (Chapter 9), Giving Your Learners Feedback (Chapter 10), and Reviewing Your Learning Experience (Chapter 11).

Each chapter contains several recommended activities, such as on page 40 of Chapter 3 when the authors describe how to build a learning map, or a “plan for designing and building your learning experience.” It gives specific examples for such activities, such as an example learning map on pages 41-2–42 from a class on how to meditate. Rosenfeld Media books are known for their accessible, down-to-earth language that make them great introductions for people who are new to a discipline; this book is now different.

As someone with significant experience in UX, instructional design, and teaching online, however, this reviewer found very valuable information in Design for Learning as well. Though I have not personally created a learning map for courses and trainings I’ve done, I’ve engaged in similar activities and the ability to name this course planning process and link it to best practices in design is significant. As an academic, I’m most excited to use this book for teaching purposes. However, as many current students in technical communication who are interested in UX may struggle to see its relevance to instructional design, where the ADDIE model is arguably the dominant paradigm.

Though I can’t speak for an entire field, Design for Learning seems to be an important bridge between instructional designers who view the ADDIE model as the best practice and UX designers who see the UX process as the best practice. The book connects UX and instructional design in simple, relatable terms that both newcomers and seasoned professionals will find useful.

Guiseppe Getto

Guiseppe Getto is a faculty member at Mercer University. He is also Director of Mercer’s M.S. in Technical Communication Management.

AI and Writing

AI and Writing

Sidney I. Dobrin. Broadview Press. [ISBN 978-1-55481-651-4. 128 pages, including index. US$19.95 (softcover).]

AI and Writing by Sidney Dobrin helps students and instructors understand how Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) works and how it can be incorporated into formal writing instruction.

Dobrin looks at GenAI from two perspectives: the conceptual and the applied. Conceptual AI addresses how artificial intelligence (AI) might impact societies, economies, and cultures and how we teach and learn writing. It also contends with ethical issues for AI use and the way in which AI technologies are developed. Applied AI deals with how to use AI responsibly, which means understanding the what ifs and whys of AI.

The author doesn’t explain how to use specific platforms, but he does offer practical instruction on using GenAI platforms for writing tasks, whether they be academic, professional, or personal. Each chapter ends with “so what?” questions and scenarios for conceptual and applied AI.

For example, in Chapter 3, Integrity, learning objectives include describing ways in which GenAI and plagiarism are connected. A question at the end of the chapter is, “So what if you use GenAI without citation? What would be the likely outcome—in terms of academic and social integrity and student learning—if we had no restrictions on these practices?” (p. 42).

One of the conceptual considerations at the end of this chapter asks, “In what ways might GenAI exacerbate student cheating [assuming that students tend to cheat when they have little interest]? Are there any ways in which it might actually discourage cheating?” (p. 42).

Finally, considerations for applied AI include asking GenAI to define plagiarism and whether using GenAI is a violation of academic integrity.

If you’re interested in evaluating the role of GenAI as a writing tool (for better or for worse), AI and Writing presents a plethora of conceptual and applied AI questions, along with discussion questions, that will have you considering its use from every angle. You’ll learn about:

- Identifying hallucinations (outputs that are false but appear correct)

- Showing your work (your writing process)

- Using GenAI for research, drafting, and revising

- Writing and refining prompts

- Creating images from words

- Developing and applying GenAI skills

This is a good read for contemplating the future of writing, especially as it applies to teaching people how to write academically and in their career of choice. Answering the questions at the end of each chapter would be time well spent for considering the ramifications of this technology.

Michelle Gardner

Michelle Gardner is a copywriter and content editor in the life sciences industry and the technology sector. She has a bachelor’s degree in journalism: Public Relations from California State University, Long Beach, and a master’s degree in computer resources and information management from Webster University.

The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is: A History, a Philosophy, a Warning

The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is: A History, a Philosophy, a Warning

Justin E.H. Smith. 2022. Princeton University Press. [ISBN 978-0-691-21232-6. 208 pages, including index. US$27.95 (softcover).]

In The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is: A History, a Philosophy, a Warning, Justin E.H Smith presents the myriad challenges and changes inherent in this age of social-mediated lives and shortened attention spans. He quickly moves towards a discussion of how the ideas that surround various human endeavors have woven together in imaginative leaps and metaphorical connections to lead to the creation of the internet and the ways of being it entails. He argues that the internet is not an aberration of history—it is instead an extension of our human “excrescence” that runs through a history of philosophers, scientists, and (sometimes) con men (p. 52). This book is not a quick summation of what the internet is—it is instead a readable, but challenging, work of philosophy and history that will likely upend the context in which the reader considers the internet and its place in history and the natural world.

The book contains five chapters. The first, “A Sudden Acceleration,” provides an incisive critique of what it means to exist in this moment of rapid change at the hands of social media and the internet in general. The second, “The Ecology of the Internet,” draws a connection between means of communication that exist in nature, such as the clicking of whales that can be heard by another whale across the globe and the attempts and triumphs of human telecommunications—from the bizarre and fantastic, such as a system of transatlantic communication involving snails, to the telegraph and the “screens and cables and signals in the ether” of the internet (p. 84). The third, “The Reckoning Engine and the Thinking Machine,” unpacks the illogical and metaphysical arguments that ground technophilic claims such as this world being a simulation and artificial intelligence (AI) truly ever being able to gain consciousness. The fourth, “‘How closely woven the web’: The Internet as Loom,” investigates the ways in which seemingly unrelated concepts interplay with each other through metaphor to help create new meanings and, subsequently, new inventions. Finally, in the fifth, “A Window on the World,” Smith presents a more personal viewpoint of how the internet serves as his window on the world through Wikipedia and through being able to see detailed pictures of distant galaxies, even during the isolation of a global pandemic.

Overall, The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is provides a unique way of seeing the often-overwhelming advance of the internet, AI, and computers in widely different contexts than most readers likely would have otherwise considered. Technical communicators looking for quick insight into a history and philosophy of the internet will have to dig a bit to find it, and Smith’s diverse approach sometimes does not feel completely justified.

Dylan Schrader

Dylan Schrader is a proposal developer at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, where he also earned MAs in English and Professional Communication.

The History of Color: A Universe of Chromatic Phenomena

The History of Color: A Universe of Chromatic Phenomena

Neil Parkinson. 2023. Frances Lincoln. [ISBN 978-0-7112-6679-7. 256 pages, including index. US$28.00 (hardcover).]

Throughout history, humans have grappled with the nature of color and its role in our world. Artists, philosophers, and scientists have all investigated the properties of colors and attempted to strengthen our societal understanding of how color works. Across the centuries these researchers collaborated, argued, and theorized with each other, ultimately developing the field of color studies. Now, in Neil Parkinson’s The History of Color: A universe of chromatic phenomena, he surveys the evolution of this field from antiquity to the modern era. Along the way, Parkinson familiarizes readers with such seminal texts as Aristotle’s On Colors, Isaac Newton’s Opticks, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Theory of Colours, to name a few.

The History of Color divides the evolution of color theory into four historical periods, with each one meriting its own chapter. The early chapters, covering the classical period through the mid-19th century, are defined by the quest to understand color. In these eras, artists and scientists had little to no grasp of what color was, or how the different colors related to each other. The various theories are mostly varying degrees of ridiculous, including such ideas as color being indicative of “cosmic power”, or that color was simply a visual representation of musical notes. Gradually the foundations of color theory were developed, such as with Newton’s revelation that color is formed from rays of light. In the latter chapters covering more recent history, the study of color shifts more to the domain of the artist, and accordingly “publications on the subject of color began to move from the ‘how’ to the ‘how-to’” (p. 134). Recent developments on color have focused more on aesthetic study, and the literature reflects this.

It is fascinating to see the gradual evolution of color theory, particularly thanks to the lavish illustrations throughout the book. It seems like every theorist developed their own color wheel to explain the relations between colors, and most of these are faithfully reproduced in The History of Color. These graphics highlight how little we understood color, and it is satisfying to chart the evolution as primary colors and eventually the modern color spectrum is identified by scientists. Still, the book does throw out many names, theories, and book titles, and it can feel a little dry to read for long periods. Thankfully, each history chapter is broken up by short essays about the impact of color in different domains. These include such contexts as food, printing, commerce, and even language. These were my favorite sections of the book, as they really emphasized how color has impacted our world.

Overall, The History of Color is an excellent survey of the evolution of color throughout our world. The chronological chapters provide a thorough if occasionally dry narrative of how color theory evolved, and the essays highlight the impacting that this evolving knowledge had on human society.

Nathan Guzman

Nathan Guzman is a graduate student studying technical communication at the University of Alabama–Huntsville. His background is in aerospace engineering with plans of becoming a full-time editor upon graduation. Nathan is an avid reader interested in reading anything that expands his knowledge of the world and how it works.

Making Sense of Mass Education

Making Sense of Mass Education

Gordon Tait, Nerida Spina, Jenna Gillett-swan, and Peter O’Brien. 2023. 4th ed. Cambridge University Press. [ISBN 978-1-0091-0532-3. 440 pages, including index. US$86.00 (softcover).]

The fourth edition of Making Sense of Mass Education argues for the role of philosophy in mass education in a digital world. Gordon Tait et al. aim to explain the context of mass education with a focus on Australia through a postmodern philosophical lens: “The mass school is a site of great ethical and epistemological complexity, and philosophy can help us make sense of it in ways the other disciplines cannot” (p. 6). In this edition of the text, the authors provide updated data and research and address the rapidly changing context of technology and Australian education, which includes discussions of school funding equity.

Tait et al. systematically analyze and offer counterpoints to the modernist sociologies in an easy-to-digest format and language. The text begins with a reassessment of the modernist conceptual framework of education through a postmodern lens then moves through a discussion of governance and the cultural contexts of contemporary education. Specifically, each chapter is structured around identifying common myths about mass education to unpack and debunk them.

The authors also argue that philosophy can address some challenges that the field of education alone does not. Part 4 focuses on the role of philosophy and mass education. “Philosophy is particularly important to education.…there have been 2500 years’ worth of disputes about exactly what it is and how it ought to work” (p. 295). The authors argue for the value of philosophy in understanding the larger structure of education, the value of the academic discipline of philosophy, and encourage educators to make use of the discipline in their work to better contextualize their role and to help them develop personal philosophies. Of particular interest, Chapter 9 explores the implications of data collection and the increasing “datafication” of contemporary mass education. Chapter 12 addresses the role of technology in education and questions if digital technology is the answer to challenges facing the education system.

Making Sense of Mass Education achieved its goal of a clear, inclusive, and accessible language. It effectively summarizes complex philosophical arguments and movements, educational law, and unpacks the role of class, sex, and race in Australian education over time. While the authors offer thoughts on alternative education and potential changes to the mass education system, they do not offer a definitive solution for these challenges in their statement, “Understanding those theories, and what they say about mass schooling, isn’t really a quest for the ‘right’ answer” (p. 401). This book is not for you if you are an educator looking for the “right” answers or an academic seeking to learn more about the history of education. However, anyone interested in the context of the philosophy and structure of education in a postmodern, digital world will find a clear, accessible discussion of the value of philosophy in understanding mass education.

Amy Mandt

Amy Mandt is an STC student member. She is the Pre-Health Program Manager at the University of Alabama in Huntsville and an MA student of technical writing. Amy previously earned her M.Ed. and taught English with more than ten years of STEM education experience.