doi.org/10.55177/tc716309

By Soyeon Lee

ABSTRACT

Purpose: This article argues that transnational multilingual entrepreneurs, particularly immigrant Asian/American small business owners, negotiate their access to disaster recovery-related resources by tactically sharing their own user cases through translocal business networks and developing local ethnocultural collaborative entrepreneurships.

Method: This study was based on a 9-month user experience study across 14 entrepreneurial sites in two cities located in U.S.-Mexico border regions.

Results: User narratives from this study demonstrate that transnational multilingual small business workers tactically adopted nuanced collaboration tactics in navigating resource-constrained environments in post-pandemic workplace settings.

Conclusion: The study findings suggest that the binary notion of use and non-use of multilingual resources and the arrangement of multilingual content in federal disaster relief programs should be reconsidered to better situate human-centered design for transnational multilingual users in workplaces in under-resourced disaster-specific bureaucratic writing contexts.

Keywords: Transnational Multilingual Entrepreneurs, Bureaucratic Writing, UX Research

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Recognize immigrant multilingual small business entrepreneurs as technical communicators.

- Prioritize the needs of underrepresented multilingual users and honor their lived experiences and community-based localization practices in multilingual workplace contexts.

- Build a nuanced knowledge about complex contexts, in which local communities of underrepresented transnational multilingual entrepreneurs are situated and their linguistically, culturally, and racially diverse experiences and embodied interactions with government agencies are embedded, in the process of developing and localizing technologies and services.

Introduction

The recent pandemic severely affected ethnic and racial minority small business owners, drawing attention from scholars, practitioners, and policy makers. Minority entrepreneurs were disproportionately disadvantaged in accessing pandemic relief resources and aid, such as the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL): “The PPP initially relied on traditional banks to deliver loans, which favored existing customers at large banks and disfavored microbusinesses (businesses with fewer than 10 employees), non-employer businesses, and Black- and Latino- or Hispanic-owned businesses (which all tend to be unbanked or underbanked)” (Liu & Parilla, 2020). Although this discussion rightly points out the social inequality in business sectors during the pandemic, it often lacks fuller attention to transnational multilingual Asian/American business owners. According to Bloomberg, “60% of Asian-owned businesses nationwide missed out on financial aid,” and “immigrant-owned small businesses, often rely[ing] on cash and paper-based bookkeeping” had difficulties in generating the “extensive documentation required for government aid applications” (Yee et al., 2021).

While their economic and social distress associated with changing technological environments and monolingual documentation systems in workplace settings has been severe, immigrant multilingual Asian/American business owners and their lived experiences have yet to be fully investigated. To address this issue, this article presents empirical findings from case studies of Korean-speaking immigrant entrepreneurs and their user experiences in navigating three disaster assistance programs: the COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL), the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), and the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program, commonly offered by government agencies under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020.

Small business owners predominantly work in less bounded places, in which “traditional and stable ideas of public space, namely the forum, the legislature, the visible and well-bounded public” (Grabill, 2010, p. 199) are not clearly visible. And in small business sectors, organizational hierarchies are often unable to be clearly defined. Entrepreneurs and their rhetorical situations in extra-institutional contexts, such as self-employed workers or small business owners, have yet to have full attention from technical and professional communication (TPC) scholars. Citing Petersen’s (2014) study, for example, Walton (2016) pointed out that “elite notions of professionalism” that focus on the context of Global North, which encompasses so-called Western developed countries, often “exclude the experiences of marginalized groups” (p. 177). Similarly, Rajan (2021a) challenged dominant narratives that focus on individual professionals in the Global North by tracing grassroots entrepreneurs in India and their rhetorical practices.

Extending this important justice research, this article presents the results from an explorative and narrative-based study of how transnational multilingual Asian/American professionals who were self-employed or ran small businesses and who often served inner-city residents and urban areas interacted with technologies administered by government agencies. User narratives from this study demonstrate that transnational multilingual small business workers tactically adopted nuanced collaboration tactics in navigating resource-constrained environments in post-pandemic workplace settings. Based on a 9-month user case study across 14 entrepreneurial sites, including convenience stores, beauty-supply businesses, and clothing stores, serving mainly other BIPOC communities or lower-income neighborhoods across two cities located in U.S.-Mexico border regions, this article argues that transnational multilingual entrepreneurs negotiate access to disaster recovery-related resources by sharing their own user cases through translocal business networks and developing local collaboration tactics, which I call ethnocultural collaborative entrepreneurships. The findings of this study suggest that the binary notion of use and non-use and the arrangement of multilingual content in federal disaster relief programs should be reconsidered to better situate human-centered design for transnational and multilingual workplace users in under-resourced disaster-specific bureaucratic writing contexts.

Research Context

It is known that immigrants tend to be more self-employed than U.S.-born workers (Kochhar, 2015, p. 9; Min, 1990, p. 436). Businesses conducted by Korean immigrants in U.S.-Mexico border regions have shaped professional social webs with international customers who cross borders. Korean immigrant business owners often called businesses in U.S.-Mexico border regions Gukgyeong Jangsa (Korean for “border businesses”), which means trades located geographically and/or socioculturally close to borders. Often, my participants referred to their pre-2000s period as a highly prosperous time when many immigrants achieved rapid economic growth and were even considered a threat to other local business professionals in the region. For example, a Korean immigrant shop owner participant said, “Some wholesalers in [another city’s name] jokingly asked us, ‘Are you dumping items in the river?’ At that time, we had more than 15 stores in just one downtown area.” Particularly, in southern border regions, Korean immigrant entrepreneurs operated businesses in textile, clothing, and variety shops, although their populations in these regions made up a smaller proportion than they did in other states such as New York, where Asian/American communities made up a relatively significant proportion.

This trend was impacted by the rapidly growing Mexico-China economic trade and relationship starting in the 2000s. According to several participants in this study, as products from China, such as textiles and shoes, started to be directly imported into Mexico, the number of customers and wholesalers from Northern Mexico was dramatically reduced. Particularly, urbanization development plans accelerated this downturn, because many sources of capital and financial support favored bigger companies such as brand name stores, outlets, shopping malls, hotels, and tourism capitals. Furthermore, Korean immigrant entrepreneurs explained that their businesses anticipated an irreversible downturn due to the new trends in the aftermath of the pandemic. Many participants in my study reported they were under inevitable capitalist (de)global and protectionist forces in the aftermath of COVID impacts, what Nail (2022) termed “COVID capitalism,” that is, “the mutual alteration and amplification of COVID and capitalism” (p. 338, emphasis in original). They also indicated nuanced aspects in COVID-amplified inequalities, in which minority-owned businesses were falling behind the rapidly changing business trends:

There are only a few business owners who can maintain service. Only a few people are owners of grocery stores or restaurants, but their location and mode of operation are important. They should be businesses that operate to-go or drive-through services because restaurants with other types of services were blocked by the city.

As “only a few” businesses were favored in the context of the pandemic, the complexity of government regulations and technological changes such as online takeout delivery services were often described as inevitable and irreversible hurdles.

Some participants explained that a smaller business was likely to receive less assistance: “[During the pandemic] I shut down my store for more than a month, but we have just two employees, including my wife. Other businesses that have many employees, they got more assistance.” Other participants also described capitalist forces that were reinforced by the COVID-19 disaster by explaining how they struggled to catch up with the changing landscape in online commerce. One participant shared that he created an online account and listed his store with the Postmates service, a startup online platform, which delivered online orders to customers from small businesses, but soon it merged with Uber:

Uber only included the biggest stores, like big liquor stores, and then cut off other smaller stores…At the beginning [of the pandemic], I received some online requests for deliveries, but after some weeks, I did not have any orders…If I’d like to follow up with it, I need to spend a great deal of money, and that’s a problem. Many business people like me can’t do it [competing against Uber-favored stores].

For small business owners like this participant, the Small Business Administration (SBA), a federal government agency, implemented the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) through banks as forgivable loans to be used mainly for payrolls and other expenses including rent, utilities, and mortgage interest costs to sustain their businesses (BEA, 2021). Despite the intention, the programs were criticized due to their disparate access, given that the nature of the distribution relied on banks as intermediaries, which were likely to benefit big companies. Based on participant’s narratives and experiences, this article mainly focuses on the PPP, the Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL), and the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) programs. While the SBA website offers program information and instructions for application forms in 17 languages, it requires applicants to submit applications in English only and does not provide concrete guidelines (SBA, “COVID-19 Relief Options,” n.d.). Against this backdrop, this article is grounded in the following research questions:

- How did transnational multilinguals in different sectors communicate with COVID-19 related programs provided by government agencies and community organizations?

- What experiences and needs did they have for documentation and as users of public services in COVID-19 recovery?

- What challenges did they face in interactions with technical documentation and/or how did they achieve their communication goals through technical documentation?

Literature Review

To study the interactions of transnational multilingual small business owners with technical services and documentation in disaster recovery, I adopted interdisciplinary frameworks at the intersections of user experience (UX), social justice research and design, and intercultural entrepreneurship scholarship in technical and professional communication (TPC). These interdisciplinary frameworks resist inherent deficit-based approaches to multilingual users and implement social justice research and design in usability studies (Acharya, 2022).

Promoting justice-oriented and participatory UX studies, Rose (2016) called for attention to “resource-constrained contexts” that include “both developing countries and vulnerable or underserved populations in developed countries” where populations are situated “with limited access to, or reduced availability of, resources” (Rose, 2016, p. 433). Rose et al. (2017) examined UX design practices of insurance healthcare guidelines that better serve the local needs of Cantonese and Vietnamese immigrant users in nonprofit settings. Social justice-oriented UX research considers “marginalized, vulnerable, and potentially ignored groups” to examine the complexity of the notion of users (Rose, 2016, p. 429). Echoing this justice-oriented UX design approach, Cardinal et al. (2020) further critically examined “damage-based” exploitation in research and design processes embedded in the “extraction model of UX” and proposed a “multilingual UX design” as a participatory approach to UX design for/with marginalized communities by foregrounding community-based language and translation practices. Lancaster and King (2022) also asked “how and why and for whom we localize” (p. 1, emphasis in original) and investigated how design can include diverse user groups in global contexts.

This study adopts these recent methodological approaches in UX research and advocates for intercultural communication in workplace contexts (Evia & Patriarca, 2012; Fraiberg, 2021; Pihlaja, 2020; Rajan, 2021a, 2021b; Thatcher, 2006). Honoring diverse rhetorical traditions in U.S.-Mexico border regions, Thatcher pointed out, “In the United States, writing reflected and reinforced traditions of individuality, universalism, equality, and common law reasoning” while “the Mexican rhetorical traditions reflected and reinforced an in- and out-group orientation that is common in collective cultures, hierarchical social organizations, and particular or relational thinking patterns” (Thatcher, 2006, p. 388). This article foregrounds Korean immigrant small business entrepreneurs as linguistically, culturally, and racially marginalized users because they have addressed unique rhetorical exigencies under extremely constrained timeframes and under-resourced conditions to sustain their businesses and manage textual engagements in the aftermath of the pandemic. Nonelite technical and communicative expertise and the work of the “grassroots entrepreneurs” (Rajan, 2021b, p. 315) need to be highlighted through more grounded approaches to the notion of entrepreneurship, which is operated “not only by a desire to create economic or social value (Sarkar, 2018) but also by a combination of necessity, interest, and the desire to help members of different occupational communities” (Rajan, 2021a, p. 273).

This study expands social justice research in technical writing (Walton et al., 2019) and usability and UX scholarship (Acharya, 2022) by investigating the localization practices of understudied marginalized users (Agboka, 2013; Dorpenyo, 2020; Sun, 2006; Sun & Getto, 2017; Rose et al., 2017; Rose et al., 2018). The technical and communicative practices of language minority migrant entrepreneurs and their textual labor in interacting with government bureaucracies have yet to be fully studied.

Method

This study (IRB No. 1838733) was conducted between November 2021 and July 2022. At the time of the study, the three programs (EIDL, PPP, and PUD) were closed, and my participants were receiving emails and letters from agencies requesting repayment of the loans or provide evidence for forgivable loans. By using community-based action research methods, I investigated the user experience (UX) of transnational multilingual small business owners in response to disaster-related government recovery programs. To highlight the lived experiences of minority entrepreneurs, this article uses UX research methods in workplace settings by networking narrative-based approaches in human-centered design (N. N. Jones, 2016) and the rhetoric of entrepreneurship (Spinuzzi, 2017). Building on the definition of entrepreneurship offered by Spinuzzi (2017), I conceptualize the notion of translocal and ethnocultural collaborative entrepreneurships, in which rhetorical agency and coalitions are enacted as central pathways to advocating for themselves as agentive technical communicators in the rhetorical process of problem-solving.

Data collection and analysis

I conducted interviews through narrative-based approaches (N. N. Jones, 2016), observations, and artifact collections to understand participants’ user experiences. At the time of the study, the federal relief programs had closed the application periods, and thus I mainly relied on participants’ voluntary recollective narratives. Narratives are powerful in their capacity “to disrupt and resist because they can create an individual’s reality while informing how that individual makes meaning of that constructed reality” and help participants “articulate their values and beliefs” (N. N. Jones, 2017, p. 328). In the field of UX, narratives, storytelling, and testimonios increasingly adopt justice-oriented methods that can empower marginalized user groups (Rivera, 2022). I first asked potential interviewees to answer a brief questionnaire that asked about their years of residence in the United States, language repertoires, technological communicative tools, and media channels through which they accessed information about COVID-19 relief aid. At the time of the interviews, participants pointed out that their accounts were already closed and that they were unable to share the interfaces of their accounts on the SBA portals. One of the challenges in studying disaster recovery technologies is that they are not easy to track down. Mostly, those accounts are closed after the relief period ends, and participants’ artifacts are often hard to collect due to their nature (e.g., participants’ financial information and affective refusal to revisit the complexity of the materials). Three participants shared copies of their application forms after deleting their information in PDF and professional emails between the SBA and themselves. I invited them to a follow-up individual interview or a group interview in a workshop format to generate ideas for actionable solutions, but one participant responded. I expanded the participant pool by snowball sampling across two cities. Interviews were mostly about 45–90 minutes. Participants preferred doing an interview in their workplaces, in a space behind their cash registers or in a small office room. I observed their daily professional activities after the interview ended and when they allowed me to stay and observe them as a researcher. For data analysis, I adopted the recently emerging “mobility system”-based approaches that investigate the transnational literacies of entrepreneurs and their complex networks and mobility in geological spaces (Fraiberg, 2021). By using constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006), I generated 183 code entries and 19 code clusters and synthesized them into two themes: collaboration and non-use of institutional multilingual content.

I revealed my background to the participants during the study. I grew up as the daughter of parents who operated a small clothing store in South Korea and, at the time of the study, had lived in the United States for about 9 years across “transnational social fields” (Levitt & Schiller, 2004, p. 1003). Given this shared position, I had an advantage, as I was able to understand cultural cues and material conditions under which immigrant entrepreneurs were situated (e.g., vulnerable to political and immigrant policy changes, public health crises such as COVID-19, and intensive working conditions, as described in one participant’s narrative, “We work for 364 days, being off for only one day, Christmas Day”). But I also acknowledge that my position cannot help me fully understand their perspectives because I am working in a different job sector and under different legal statuses in the United States than they are.

I recruited 20 participants across two cities and, out of the 20 participants, 16 reported that they were self-employed or were small business owners. Participants’ ages varied: one participant was in the age range of 35–44 while five participants were in the range of 45–54, five participants were in the range of 55–64, and six participants were in the range of 65–74. Out of 20 participants, 16 people were small businesses owners and had often worked (previously or at the time of the study) as local nonprofit community workers while four participants were community workers without having business ownership. Out of 16 business owner participants, one participant identified as female while 15 participants identified as male. Out of 16 small business owners, 14 reported that they applied for at least one of the federal aid programs. Out of 16 participants, other than English, 12 people reported they speak mainly Korean, three participants speak Korean and Spanish, and one participant speaks Korean and Chinese, both as primary languages. While most participants had lived in the United States more than 15 years, the years of residency varied: 15–29 years (n=8) and 30–44 years (n=8). Their businesses ranged from small retail stores (n=8, clothing, convenience, beauty supplies, and other types of stores) to service providers (n=6, restaurant, custodial, and other services).

Findings

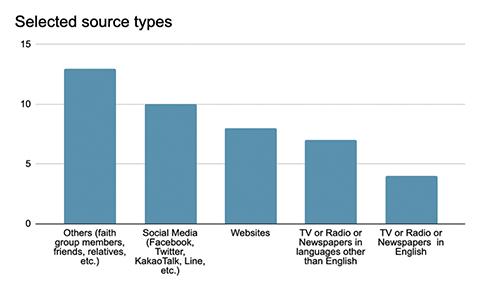

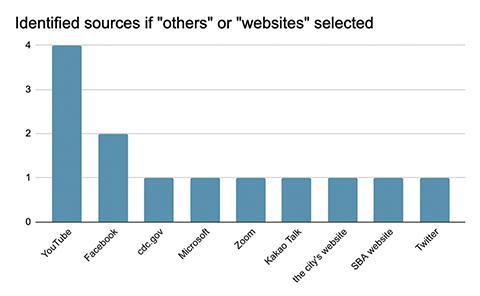

The results of the questionnaires (n=14) show how the participants accessed information about COVID-19 recovery-relevant public programs for small businesses. In multiple choice questions about source types, the participants mostly selected the categories of “other” (n=13), “social media” (n=10), and “websites” (n=8) rather than traditional news sources such as TV, radio, or newspapers (Figure 1). Those who selected “other” as main sources shared that many of them used YouTube (n=4) (Figure 2). These questionnaire-based results helped me understand their interviews and synthesize the narratives and emerging themes with their media environment contexts. Overall, changes in technology played a significant role in their daily entrepreneurial activities. The interviews showed that social media platforms such as KakaoTalk—an instant messaging app widely used in Korean communities—were used to gain knowledge about what public programs were available, when they started, and how other business owners worked on their application forms. Axial coding of the interviews produced two sub-themes around collaboration, which emerged against “documentary governance” (Smith & Schryer, 2008, p.140) and the “textual authority” (Devitt, 1991, p. 347) in bureaucracy and workplace contexts.

Overall, participants’ interviews indicated how the participants managed the application process through collaboration. Instead of talking about challenges or pain points throughout the recovery process such as “language barriers” and lack of “access,” participants detailed how they communicated with their friends and co-workers through their personal networks on YouTube and KakaoTalk to learn about the programs and complete the application form submissions.

Examining different narratives revealed that, unlike the government websites’ assumption that the application writing process occurs between one individual applicant and the form, the participants’ activities were collaborative processes. Many participants were unclear about what the programs were and what details were involved due to the distributed nature of the process they adopted. They said that they could not remember many parts of the process. Their accounts were already closed, and they did not want to look back at them in detail, as memories about them were entangled with emotion and embodied labor. In many cases, they were required to bring supplementary documents that proved the number of their employees, their status, and tax reports, which entailed multiple steps. This volatility of the textual materials in their narratives was common across participants.

In the following sections, I will describe collaborative rhetorical tactics my applicant participants (n=14) adopted during the process with public recovery systems and programs. In interactions with these public recovery systems, participants leveraged a wide range of what Kimball (2017) called “radical sharing” (p. 4). To de Certeau’s two tactics, la perruque and bricolage, Kimball (2017) added “radical sharing” as a third tactic that can be described as a “newfound individual capability of sharing our tactics with people the world over at great speed and with great effect” (p. 4), based on the Internet infrastructure. This sharing practice contrasts with a typical understanding of users of application forms, that is, users who are “conceived of as isolated autonomous consumers, or as self-conscious groups” (p. 2). Helped by S. L. Jones’s (2005) continuum, emerging themes will be presented in three sections: less overt collaborative interactions (translocal or contextual collaboration), more overt collaborative interactions (ethnocultural collaboration), and non-use of institutional multilingual content. The first two types of collaborative interactions exemplify the notion of Kimball’s (2017) radical sharing, in which migrant entrepreneurs gained agency in “making things happen” (p. 4), and further extend the radicalness in their sharing by critically intervening in unequally networked systems through collaboration based on linguistic, cultural, racial, and ethnic identities.

Managing Less Overt Collaborative Interactions and Translocal Literacy Networks

Extending the notion of collaboration, described as “interaction by an author or authors with people, documents, and organizational rules in the process of creating, creating documents” (S. L. Jones, 2005, p. 450), I use the term collaboration to describe those organizational writing activities that entail interactions with other people and technologies including documents, web-based documents, and administrative rules in multilingual and multimodal contexts. Proposing a taxonomy, S. L. Jones (2005) coined the term less overt collaboration and described this collaboration as contextual collaboration, given its complex interaction that “involves the context of the organization itself” (p. 450). Contextual collaboration was originally proposed by Winsor (1989) to describe the context in which “any individual’s writing is called forth and shaped by the needs and aims of the organization, and that to be understood it must draw on vocabulary, knowledge, and beliefs other organization members share” (p. 271).

Overall, interviews suggested that participants were adaptive to changing policies and programs by completing contextual interactions through digital tools such as mobile applications and web-based materials. Participants often assembled digital technologies and user-generated instructions through YouTube. I would call this group of participants (n=9) those who self-regulated the application processes through less overt collaboration that is centered on translocal online literacy networks.

Often, this group of participants said they needed to contact their CPAs, remotely located yet Korean-speaking CPAs in other states, or friends to seek information about the public programs or do what S. L. Jones termed “document borrowing” (p. 452), that is, “collaborating by borrowing from other documents, generally ones existing prior to the current writing task” (p. 452). The participants said that they leveraged genre knowledge, such as accounting terminology and financial literacy obtained from other applicants’ cases via YouTube and comments under the videos or other social media platforms, which is similar to “contextual collaboration” (S. L. Jones, 2005; Winsor, 1989). This group of participants often said that the application form itself was not hard and the questions in the form were generally in plain language. However, they also reported that the words were ambiguous in certain areas.

To address this ambiguity, this group of participants reported that they believed that computer skills augmented English skills in the application process. For example, one participant explained that managing applications via the Internet is more important than reading, speaking, and writing in English: “I don’t speak English well. But I can do the Internet well …. Everything needs to be done through computers.” This interview excerpt means that for participants, computer skills can be more productive in the application process although they feel somewhat less confident working with English only monolingual materials. The most important resources are not English skills but the ability to understand materials through digital tools that can help them network with or consult materials or instructions from other small business owner applicants, often remotely located, and work with them on the application.

Another participant reported that he used YouTube materials and media channels in Korean:

In the beginning, it was very hard to understand the process of the program. So, I followed multiple YouTube channels about the PPP application and watched relevant YouTube videos all the time to catch up on the updated information about PPP. The polices and guidelines from the SBA were changing too frequently, and I relied a lot on YouTube videos and comments below those videos.

This participant’s response also offers an example of “less overt collaboration,” as he relied on previous application cases and experiences to gain knowledge about its genre-based terms (e.g., accounting terminology) from other distant applicants. Another participant talked about how he used YouTube to learn from other small business owner applicants and CPAs who updated shifting policies.

I did the form on my own. You know, English is not my language, but if you go to YouTube, there are lots of applicants …. The problem is that those languages are ambiguous even in forms in Korean. Then, you can imagine how ambiguous those forms in English would be. But by using Korean applicants’ cases, other applicant’s cases, and multiple YouTube channels by CPAs, I compared them to each other.

Other participants reported that they networked with other transnational entrepreneurs through social medial platforms such as KakaoTalk for information in other states, where information in Korean was more abundant and quickly circulated. For example, a participant who started a business five years ago after moving from another state explained that he actively used information from friends through translocal networks, where many Korean immigrant populations exchanged information about disaster recovery programs for small business owners. Other participants’ narratives also display that they often less overtly collaborated with Korean online communities or Korean-speaking CPAs, located in other states.

These user narratives, which highlighted YouTube as a place for translocal online communities in which they examined other user cases, show how radical sharing occurred in the disaster recovery process in using translocal networks that often compensated for their self-reported lack of English skills, the ambivalent meaning of the form, and changing bureaucratic policies that govern the programs in disaster recovery-specific situations.

Coordinating More Overt Collaborative Interactions through Local Ethnocultural Networks

While some participants operated the application processes in a self-regulated way through less overt collaboration, other participants used more overt collaborative interactions and local ethnocultural networks. Specifically, those who showed more overt collaborative interactions showed what S. L. Jones (2005) referred to as “hierarchical collaboration” (p. 459). This group of participants (n=5) displayed a kind of mentoring interaction, in which one experienced applicant offered advice or mentorship in person to other applicants. Some participants who ran small retail stores mentored by generally using digital tools and web-based media literacies such as translation apps and local news media. Other participants leveraged this mentorship and human relations to navigate the application process in resource-constrained contexts. For example, one participant volunteered to help other Korean immigrant small business owner applicants apply for the programs while inviting them to his store.

This participant further explained that he read two local newspapers and two Mexican newspapers to publish bi-monthly local Korean newspapers, which is unpaid volunteer work he started five years before the time of the interview. While using multiple digital translation apps, including Google Translate and Google Lens, he compared what he translated in Korean with other media including YouTube channels. As a local newspaper editor, he particularly emphasized the point that he wanted to meet the needs of Korean immigrant small business owners including himself, who lacked locale-specific news about relief programs which was covered neither by local news nor by national English newspapers: “I read four newspapers: [city name] Times and presses from Mexico. Although I don’t speak Spanish, I can translate them. Google Translate translates all languages into Korean. I am responsible for delivering correct information.”

The same manner was applied in his approach to translation. The participant said that he used multiple translation apps. He showed how he daily used Google Translate and Google Lens to crosscheck if the meanings of the words and website information he intended to deliver were correct. By gathering information from diverse news media and websites and translating information into Korean, he helped more than 20 local business owners near his own store access information about the public relief programs.

The user narratives of those who got help from this participant exemplify how a more overt collaborative action occurred. Commonly, they assigned power and agency to other experts or applicants and actively collaborated with each other to complete the applications through in-person communication and verbal group communications. One participant, who runs a restaurant said, “I don’t know what I don’t know. I don’t know what PPP is, what SBA is, I just know that government helps us with aid, then, I would say, then, okay. But I don’t know what SBA is, I don’t know what exactly SBA is. But I think I should get help. I reported my incomes and paid taxes for 20 something years.” Often, participants said they don’t know what they don’t know and do not access information through TV, radio, or newspapers as they don’t have time to view them. This participant also said, “Do you think I have time to watch TV? I don’t have time for that. Anyway, I can’t watch TV as I don’t know English.” Participants often shared how they stopped learning English after they attempted to meet their own desire to learn English: “When I started my business, I didn’t know English or Spanish. I went to community college to learn English, I went up to the level 7 out of 10, but I needed to run my business and study English at the same time; it [doing both] was too hard once the level went beyond 7.” Negotiating their literacy, access to information, and rhetorical agency, these participants leveraged personal networks, human relations, social media, and resource coordination to learn about the presence of recovery programs and apply for them.

When asked what if there were no expert or more experienced applicants around them, one participant said: “Why are you asking that? [laughing] There ARE resources. In that case, I will find another person.” Then, he continued:

Maybe, it would be very hard. But why are you saying there would be no one, although there is actually one. What if there is no one like a hyeongnim [Korean for brother], you mean? Then, I will find other young Korean transnational business owners who can speak English, maybe I would ask them to help me with the application process. I would say, literally I can’t do it [the application process] on my own.

This participant’s interview suggests that participants compensated their lack of resources and self-reported literacy skills with their ethnocultural resources. In this sense, more overt collaboration in post-pandemic contexts among Korean immigrant entrepreneurs is similar to migrant workers from Mexico who learned English in their own way in the basement of a grocery shop in a small town in a Midwestern state, described in Kalmar’s (2001) ethnographic work (p. 22) or immigrant Latinx custodial workers whose literate repertoires and knowledge are unfairly undermined in workplaces by “white English supremacy” (Remigio Ortega et al., 2022, p. 36), in that their literacy work and labor across different contexts are commonly entangled around racial discrimination, monolingual paradigms, and xenophobic climates against migrant workers of color and emerged as self-reliant pathways to sustain not only their professional lives but also their own human dignity based on their race and ethnicity, by “inverting the hierarchy” (Kalmar, 2001, p. 21).

Another participant, who ran a small retail store, also reported his overt collaboration with other applicants. However, it should be noted that overt collaboration does not necessarily lead to successful procedures or results. For example, he reported that he ended up returning the benefits he received to the government agency.

But, on a website, I happened to see a Korean lawyer’s comments about other applicants’ cases that are similar to my temporary worker [visa type] status and applications. The comments said that those cases are not supposed to take the benefits. I was scared, so I returned the benefits I received by returning a check. Some months later, the office called me, and they said I was eligible to receive the benefits. But I just left it as it was [returned] and did not apply for them again.

The uncertainty created lots of tension and distress (“I was scared”) and took emotional labor as he needed to negotiate with immigration-relevant policies and communicate with the office to confirm his eligibility.

Overall participants’ interviews suggest that creating a rhetorical network or flow is more important than translating words in the form or instructions. This group of participants often shared their challenges stemming from linguistic and cultural differences, and this shared history seemed to enable them to create an ethnocultural community in which members help other members in a timebound and resource-constrained situation, based on their communal embodied experiences while doing business.

Non-Use of Institutional Multilingual Content

Except for one participant, interviewees mostly mentioned that they did not use translated materials in Korean provided by government agencies for the application process. Neither group mentioned a Korean translation, except for one participant, and their user narratives suggested that only one participant used the Korean translations of the forms and instructions.

In my observation of the website, forms in Korean were listed, along with other multiple instruction or information sheet files, without a hierarchical design. Therefore, it was hard to see the presence of the forms in Korean. More importantly, information in plain language that the website promised to comply with in offering public programs in the form or information sheets does not seem to align with language accessibility (SBA, “Plain Language,” n.d.). For example, the phrase “a final balloon payment” (emphasis in original) observed from my participant’s SBA email artifact or “safe harbor” observed from a PPP form in PDF look plain and clear, but these are in fact jargon and financial terminology and need more contextual explanation. In the document translated into Korean, “safe harbor” is translated as Anjeon Gyuchik, which can be back translated into “safety rules.” From the left side menu of the SBA website, a section titled “COVID-19 Recovery Information in Other Languages,” an obvious typo remained the same throughout my study period: “신청서는 드시 영어로 제출해야 합니다. 아래 문서는 모두 정보 제공 목적으로만 제공됩니다,” which can be back-translated to “your application st (the first syllable “mu” missing from the word “must”) be submitted in English. The following documents are provided for information purposes only” (SBA, “PPP Loan Forgiveness,” n.d.). Also, in the PDF form titled “Economic Injury Disaster Loan Supporting Information” (SBA, “EIDL Supporting Information,” n.d.), the multilingual applicant was told in a more threatening tone: “I certify under penalty of perjury under the laws of the United States that the foregoing is true and correct” was translated into Korean as “본인은 상기 내용이 사실이며, 위증 시 미국 법률에 따라 처벌받는다는 것을 인증합니다,” which can be back-translated into the sentence “I certify that the foregoing is true and correct and that, in case of perjury, I will be punished by the laws of the United States.” This observation is similar to the findings of analyses of language in mortgage documents (N. N. Jones & Williams, 2017) and of the instruction documents of the asylum application (Sims, 2022), in which plain language itself does not lead to justice. Human-centered design needs to be implemented to address inequality and injustice embedded in technical documents and the materiality of the text and form.

The participants seemed to be acutely aware of these power structures, embedded in the web-based infrastructures of the programs. Although the SBA website offers “multilingual” information, it does not seem to be scanned, noticed, and used by potential applicants. As N. N. Jones and Williams (2017) noted, delivering complex information requires “recalibrating our understanding of plain language’s purpose, with an eye toward design and not just information dissemination” (p. 428). The design of the multilingual section of the SBA websites seemed to work like a “file cabinet” (Redish, 2012, p. 3) rather than a usable interface designed to help applicants find resources and feel empowered to complete the process. This finding can be supported by the fact that although multilingual resources were offered on the website, the participants, particularly the participants who used a more overt collaboration, did not use these resources and thus seemed to be closer to non-users, specifically, the “rejecters” or the “excluded” (Wyatt, 2003, p. 67).

Discussion and Conclusion

These user narratives advocate the reconsideration of the multilingual use of public systems and programs. The participants’ use and textual labor in application procedures entail collective care, emotion, and affective and embodied practices, which are often entangled with community histories, racial experiences, and entrepreneurial contexts under disaster-specific capitalism and global forces. Commonly, they rejected or were excluded from multilingual resources and alternatively arranged translocal and ethnocultural collaborative entrepreneurships. Their “radical sharing” (Kimball, 2017, p. 4) based on digital infrastructures and ethnocultural networks seemed to be enacted by grassroots community empowerment and implemented due to their own hesitance about using institutional multilingual resources or resistance against implicit logics embedded in them, often based on deficit-based approaches to minority users, even though those resources seemingly looked inclusive.

This research has demonstrated that transnational multilingual small business owners leveraged radical sharing at two levels in a resource-constrained: less overt collaborative interactions and more overt ethnocultural collaborative interactions. Furthermore, the context of how multilingual resources were offered also seemed to be important. Multilingual resources were not established from the beginning and were not provided consistently across different types of documents (e.g., information sheets, forms, and instructions for each program), and thus the participants were often unaware of the presence of multilingual resources. This irregular and inconsistent content arrangement led to the failure to build trust between government agencies and minority small business owner applicants who were already constrained by time and resources. This study shows that transnational multilingual users mostly navigated the application process of public programs without official translations. In workplace writing studies and human-centered design scholarship, this study is consistent with the findings from other multilingual UX studies and social justice research and design work in technical writing (Cardinal et al., 2020; Rose et al., 2017). Beyond the correctness of translation, even beyond plain language discourses in bureaucratic writing, it is more important to design when, how, and where multilingual content is situated and localized in consideration of specific community-based contexts.

[T]he design, development, and dissemination of multilingual content relies not only on successful translation of written information, but also on ethical collaborations between communication designers and the multilingual communities we increasingly seek to support. Multilingual communication design is a rhetorically situated practice that should be informed by the expertise of multilingual users (Cardinal et al., 2020, p. 2).

In sum, transnational multilingual users’ narratives help us complicate the binary of use and non-use of institutional multilingual resources and understand minority small business owners’ non-use or rejection of multilingual resources and their ethnocultural radical sharing, which is similar to work of “information coordinators” (S. L. Jones, 2005, p. 464). Their narratives suggest that in a more necessity-driven context (Rajan, 2021a, 2021b), the binary of user and non-user needs to be reconceptualized because those views tend to flatten differences between users or non-users and multilayered and embodied contexts. Small business owners mostly had to adapt their tasks to the roles of technical writers, accountants, and collaborators in response to the digital environment for application processes (e.g., email accounts, government portals, and digital forms) and resource-constrained contexts.

Given the specificity of the pandemic, disaster recovery programs for small businesses, relevant policies, and criteria were newly implemented and constantly changing. Institutional multilingual arrangements reinforced monolingual paradigms, in which those resources were translated without considering multilingual users’ contexts and embodied labor under material conditions and resource-constrained contexts. Transnational multilingual entrepreneurs enacted their agency drawing from collective knowledge gained from translocal ethnic communities and technological resources. Their narratives highlight the need for future research to further involve their practices and perspectives at an early design stage and the need to consider a more nuanced way to promote diversity, equity, inclusion, and social justice in technical communication between government agencies and minority entrepreneurs.

Acknowledgements

I thank the participants in this study, who shared their time and stories during their daily business hours. This project was supported by the Career Enhancement Awards from the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Texas at El Paso.

References

Acharya, K. R. (2022). Promoting social justice through usability in technical communication: An integrative literature review. Technical Communication, 69(1), 6–26. https://doi.org/10.55177/tc584938

Agboka, G. (2013). Participatory localization: A social justice approach to navigating unenfranchised/disenfranchised cultural sites. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22(1), 28–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2013.730966

BEA (Bureau of Economic Analysis U.S. Department of Commerce). (2021, May 17). Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://www.bea.gov/help/faq/1408

Cardinal, A., Gonzales, L., & Rose, E. J. (2020). Language as participation: Multilingual user experience design. In Proceedings of the 38th ACM International Conference on Design of Communication (SIGDOC ‘20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, Article 28, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1145/3380851.3416763

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

Devitt, A. (1991). Intertextuality in tax accounting: Generic, referential, and functional. In C. Bazerman & J. Paradis (Eds.), Textual dynamics of the professions: Historical and contemporary studies of writing in professional communities (pp. 336–357)University of Wisconsin Press.

Dorpenyo, I. (2020). User localization strategies in the face of technological breakdown: Biometric in Ghana’s elections. Palgrave Macmillan.

Evia, C., & Patriarca, A. (2012). Beyond compliance: Participatory translation of safety communication for Latino construction workers. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 26(3), 340–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651912439697

Fraiberg, S. (2021). Unsettling start-up ecosystems: Geographies, mobilities, and transnational literacies in the Palestinian start-up ecosystem. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 35(2), 219–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651920979997

Grabill, J. T. (2010). On being useful: Rhetoric and the work of engagement. In J. M. Ackerman & D. J. Coogan (Eds.), The public work of rhetoric: Citizen-scholars and civic engagement (pp. 193–208). University of South Carolina Press.

Jones, N. N. (2016). Narrative inquiry in human-centered design: Examining silence and voice to promote social justice in design scenarios. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(4), 471–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616653489

Jones, N. N. (2017). Rhetorical narratives of Black entrepreneurs: The business of race, agency, and cultural empowerment. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 31(3), 319–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651917695540

Jones, N. N., & Williams, M. F. (2017). The social justice impact of plain language: A critical approach to plain-language analysis. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 60(4), 412–429. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2017.2762964.

Jones, S. L. (2005). From writers to information coordinators: Technology and the changing face of collaboration. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 19(4), 449–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651905278318

Kalmar, T. M. (2001). Illegal alphabets and adult literacy: Latino migrants crossing the linguistic border. Routledge.

Kimball, M. A. (2017). Tactical technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2017.1259428

Kochhar, R. (2015, October 22). Three-in-ten U.S. jobs are held by the self-employed and the workers they hire: Hiring more prevalent among self-employed Asians, Whites and men. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2015/10/22/three-in-ten-u-s-jobs-are-held-by-the-self-employed-and-the-workers-they-hire/#:~:text=Self%2Demployed%20Americans%20and%20the,available%20for%20the%20first%20time

Lancaster, A., & King, C. S. T. (2022). Localized usability and agency in design: Whose voice are we advocating? Technical Communication, 69(4), 1–6.

Levitt, P., & Schiller, N. G. (2004). Conceptualizing simultaneity: A transnational social field perspective on society. International Migration Review, 38(3), 1002–1039. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00227.x

Liu, S., & Parilla, J. (2020, September 17). New data shows small businesses in communities of color had unequal access to federal COVID-19 relief. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/new-data-shows-small-businesses-in-communities-of-color-had-unequal-access-to-federal-covid-19-relief/

Min, P. G. (1990). Problems of Korean immigrant entrepreneurs. The International Migration Review, 24(3), 436–455. https://doi.org/10.2307/2546368

Nail, T. (2022). What is COVID capitalism? Journal of Social Theory, 23(2–3), 327–341, http://doi.org/10.1080/1600910X.2022.2075905

Petersen, E. J. (2014). Redefining the workplace: The professionalization of motherhood through blogging. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 44(3), 277–296. https://doi.org/10.2190/TW.44.3.d

Pihlaja, B. (2020). Inventing others in digital written communication: Intercultural encounters on the U.S.-Mexico border. Written Communication, 37(2), 245–280.

Rajan, P. (2021a). Making-do on the margins: Organizing resource seeking and rhetorical agency in communities during grassroots entrepreneurship. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 35(2), 254–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651920979999

Rajan, P. (2021b). Making when ends don’t meet: Articulation work and visibility of domestic labor during do-it-yourself (DIY) innovation on the margins. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(4), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2021.1906449

Redish, J. (2012). Letting go of the words: Writing web content that works (2nd ed.). Morgan Kaufmann. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2010-0-67091-X

Remigio Ortega, G., Guzman Gomez, A., & Marotta, C. (2022). Innovaciones y historias: A home- and community-based approach to workplace literacy. Community Literacy Journal, 16(2), 22–46. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/communityliteracy/vol16/iss2/31

Rivera, N. K. (2022). Understanding agency through testimonios: An indigenous approach to UX research. Technical Communication, 69(4), 8–26. https://doi.org/10.55177/tc986798

Rose, E. J. (2016). Design as advocacy: Using a human-centered approach to investigate the needs of vulnerable populations. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(4), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616653494

Rose, E. J., Edenfield, A., Walton, R., Gonzales, L., Shivers-McNair, A., Zhvotovska, T., Jones, N., Garcia de Mueller, G. I., & Moore, K. (2018). Social justice in UX: Centering marginalized users. In Proceedings of the 36th ACM International Conference on the Design of Communication (SIGDOC ‘18). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 21, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1145/3233756.3233931

Rose, E. J., Racadio, R., Wong, K., Nguyen, S., Kim, J., & Zahler, A. (2017). Community-based user experience: Evaluating the usability of health insurance information with immigrant patients. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 60(2), 214–231. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2017.2656698

SBA. (n.d.). COVID-19 relief options. Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://www.sba.gov/funding-programs/loans/covid-19-relief-options/covid-19-economic-injury-disaster-loan/about-targeted-eidl-advance-supplemental-targeted-advance

SBA. (n.d.). EIDL supporting information. Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://www.sba.gov/document/support-covid-19-eidl-supporting-information#korean

SBA. (n.d.) Plain language. Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://www.sba.gov/about-sba/open-government/information-quality/plain-language

SBA. (n.d.). PPP loan forgiveness. Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://www.sba.gov/document/support-faq-about-ppp-loan-forgiveness#korean

Sims, M. (2022). Tools for overcoming oppression: Plain language and human-centered design for social justice. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 65(1), 11–33, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2022.3150236.

Smith, D. E., & Schryer, C. F. (2008). On documentary society. In C. Bazerman (Ed.), Handbook of research on writing: History, society, school, individual, text (pp. 113–127). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Spinuzzi, C. (2017). Introduction to special issue on the rhetoric of entrepreneurship: Theories, methodologies, and practices. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 31(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651917695537

Sun, H. (2006). The triumph of the users: Achieving cultural usability goals with user localization. Technical Communication Quarterly, 15(4), 457–481. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15427625tcq1504_3

Sun, H., & Getto, G. (2017). Localizing user experience: Strategies, practices, and techniques for culturally sensitive design. Technical Communication, 64(2), 89–94.

Thatcher, B. (2006). Intercultural rhetoric, technology transfer, and writing in U.S.-Mexico border Maquilas. Technical Communication Quarterly, 15(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427625tcq1503_6

Walton, R. (2016). Making expertise visible: A disruptive workplace study with a social justice connexions: An International Professional Communication Journal, 4(1), 159–186. https://doi.org/10.21310/cnx.4.1.16wal

Walton, R., Moore, K., & Jones, N. N. (2019). Technical communication after the social justice turn: Building coalitions for action. Routledge.

Winsor, D. A. (1989). An engineer’s writing and the corporate construction of knowledge. Written Communication, 6(3), 270–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088389006003002

Wyatt, S. (2003). Non-users also matter: The construction of users and non-users of the Internet. In N. Oudshoorn & T. Pinch. (Eds.), How users matter: The co-construction of users and technology (pp. 67–79). The MIT Press.

Yee, A., Tartar, A., & Cannon, C. (2021, October 28). New York’s once-thriving Asian businesses struggle to recover from 4,000% unemployment spike. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-nyc-asian-american-recovery/

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Soyeon Lee is an assistant professor of Rhetoric and Writing Studies at the University of Texas at El Paso. Her research focuses on transnational environmental communication, user experience studies, and community-based approaches to technical writing. Her research has appeared in Composition Forum, Journal of Rhetoric, Professional Communication, and Globalization, and Technical Communication Quarterly. Email: slee15@utep.edu