doi.org/10.55177/tc884289

By Danielle De Arment-Donohue

ABSTRACT

Purpose: This article investigates why workplace lactation law, guidance, and policy may fail to support women. It examines the epistemological and ethical bases of technical communication governing Virginia K–12 teachers and considers complex material conditions and opportunities for social justice intervention.

Method: I employed a qualitative critical discourse analysis of three Virginia codes governing workplace lactation and one state human resources guidance document, examining their interaction with the Federal Labor Standards Act and 10 local school district policies. I drew on Technical and Professional Communication (TPC) social justice scholarship, disability studies, and apparent feminism scholarship to interpret my findings.

Results: Documents governing workplace lactation are based on an ableist mindset that marginalizes women’s bodies. They prioritize an ethic of expediency, draw on medical knowledge while ignoring women’s knowledge and material conditions, and perpetuate systemic inequities.

Conclusion: To promote social justice, technical communicators should continue questioning the epistemological and ethical bases of laws, policies, and guidance since documents informed by knowledge and ideologies that devalue the people they purport to protect will fail in implementation. Local policymakers need not wait for institutional changes but can look for opportunities to reimagine design approaches and intervene to create supportive, inclusive workplaces.

Keywords: Workplace Lactation, Technical Communication, Social Justice, Apparent Feminism, Disability Studies

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- To avoid perpetuating systemic inequities, technical communicators (TCs) should evaluate epistemological and ethical underpinnings of existing policies and question whose knowledge documents silence.

- Those designing local workplace policies can look to expand worker support and inclusivity, especially when federal or state agencies create gaps through vague language or absences and/or defer to their authority.

- TCs may seize opportunities to create more equitable workplaces by employing human-centered participatory design, drawing on apparent feminism to increase stakeholder support, and reallocating resources.

Introduction

In 2010, I stood in a faculty bathroom at my job teaching night school in a large, well-funded Virginia public school district, listening to my breast pump’s rhythmic whomps. I had taken a leave of absence (a privilege many do not have) from my full-time high school teaching job when my son was born because I couldn’t figure out how to navigate early motherhood and devote myself to work. Keeping what had been a second job allowed me to continue doing what I loved. Thankful for a flat surface to rest my pump on, I tried to relax as I leaned against the cracked chest of drawers someone had brought in to house teachers’ hygiene products. The minutes between my two classes ticked away. Someone knocked, and I hollered, “Occupied!” I remember feeling guilty about taking up this space for the whole break, stressed I wasn’t producing enough milk, and worried about finishing this job to get back to the work of teaching down the hall.

Many women are torn between the good mother ideal (Hausman, 2012) and workplace norms (Spitzmueller et al., 2018), creating an impossible tension between caring for their children and their professional duties, especially when institutions fail to recognize the labor that childcare requires. The incompatibility of these two ideals reinforces Durack’s (1997) problematization of the “dualistic thinking that severs public and private, household and industry, and masculine and feminine labor” (p. 257).

Breastfeeding has been historically characterized by shifting epistemological tensions between the medical field, cultural and social forces, and women. Early scholarship on breastfeeding rhetoric (Hausman, 2000; Koerber, 2005, 2006a, 2006b) traces tensions that emerged as the medical community, which formerly embraced the measurable technology of bottle-feeding, reckoned with science demonstrating human milk’s health benefits, leading organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in 1997 to declare it the “normative” standard for infant feeding (Koerber, 2006a). While establishing a norm may problematically position those who are unable to breastfeed, even those who are able and interested are often stymied by social and cultural forces. Today, the AAP (2022) recommends six months of exclusive breastfeeding and encourages continuing along with solid foods, citing benefits beyond one year for children but also mothers, who can experience protections from diseases such as diabetes and cancer. They also call for policies that protect against “workplace barriers” (para. 5).

Kindergarten through 12th grade (K–12) public school teachers are in a particularly complex position due to the nature of their workplaces and exemption from the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) because they do not qualify for overtime. In March 2010, the FLSA was amended to require employers provide reasonable break time and “a place, other than a bathroom, that is shielded from view and free from intrusion from coworkers and the public, which may be used by an employee to express breast milk” (U.S. Department of Labor, r.1). The U.S. Department of Labor (2010) “encourages employers” to provide breaks to employees not covered under FLSA and directs them to state laws (Reasonable Break Time). As of August 2021, 30 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico have laws governing breastfeeding in the workplace (NCSL, 2021).

Virginia recently added workplace lactation legislation, yet when I returned to teach in a small, rural district from 2017–2021, I witnessed women continuing to struggle to pump while maintaining professional expectations. Hausman et al. (2012) shed light on why many women do not end up breastfeeding—a path more common for Black and poor women. They describe how the “Social-Ecological Model” in public health considers social influences and how “choice paradigms” paint women as simply making choices in a bubble, uninfluenced by cultural and social forces around them (p. 6). This framing helps explain why, despite some legal efforts to acknowledge individuals’ needs, women still face challenges. Studying technical documents reveals how existing power structures sustain injustice and marginalization and uncovers opportunities for technical communicators (TCs) to intervene (Agboka & Dorpenyo, 2022; Walwema & Carmichael, 2021). My qualitative study draws on feminist scholarship and disability studies, employing critical discourse analysis (CDA) of recent Virginia law, guidance, and policies, to discover:

- How do Virginia workplace lactation laws and guidance position employees, employers, and knowledge of lactation practices?

- What values do documents governing workplace lactation espouse?

- What factors complicate the implementation of lactation law, guidance, and policy in Virginia K–12 public schools?

To answer these questions, I review relevant scholarship; describe my methods and application of CDA; and discuss my findings, which reveal how state technical documents: (1) position lactation as a disability and signal whose bodies are welcome and unwelcome in the workplace, (2) are driven by an ethic of expediency that prioritizes institutions’ economic bottom-lines and productivity over women’s and children’s well-being, and (3) position employers as judges, privileging medical knowledge while disregarding women’s experiential knowledge and material conditions. Examining Virginia K–12 teachers’ working conditions, especially since the Covid-19 pandemic, highlights problems many industries face, such as staffing shortages and aging buildings with space limitations, conditions that disproportionately impact BIPOC women, who may face additional discrimination. I conclude by building on existing scholarship to suggest how TCs can reevaluate existing policies’ epistemological foundations to create more equitable workplaces by drawing on human-centered design and apparent feminism, which “invites participation from allies who do not identify as feminist but do complementary work” (Frost, 2018, p. 27).

Literature Review

Technical Documentation and Injustice

Recent turns toward cultural and social justice in technical professional communication (TPC) scholarship have exposed the myth of the apolitical, neutral technical document (Rose, 2016; Jones & Williams, 2017; Sims, 2022). Walwema and Carmichael (2021) urge TPC scholars to examine the language of documents with high stakes to see whom they privilege and marginalize. Jones and Williams (2022) encourage scrutiny of documents to record and question what is missing to account for silenced voices and actively seek information to address gaps. These approaches help unearth values and epistemological bases of workplace lactation documents.

Steven Katz (1992) focuses on people documents affect, warning TCs about the consequences of an ethic of expediency. His analysis of a Nazi memo reminds us that writing in a technically proficient manner preoccupied with maintaining an organization’s ethos can have dire impacts. An ethic of expediency dominates legal language and guidance governing lactation, creating problematic consequences for women in workplaces. Kimberly Harper’s (2020) critical discourse analysis of legal decisions and pregnancy literature reveals the centering of white motherhood and the silencing and maligning of Black mothers, exposing how biases in policy and implementation lead to life-threatening vulnerabilities and inequities.

Scholars such as Sims (2022) focus on human-centered design approaches and the action component of social justice in TPC. Such methods would counter the institutional ethos that has been passed down through reiterated language from the federal to state to local level in workplace lactation documents. Colton and Holmes (2018) call for TCs not to passively await institutional changes but actively seek justice and equity “within, alongside, and beyond institutional redress” (p. 21).

Disability Studies Lens

Though lactation is not considered a disability, the legal sphere discusses lactation in terms of limitations and accommodations. This common language and lactation’s liminal positioning makes aspects of disability studies particularly relevant to analyzing ideological underpinnings in legal and cultural views of the lactating body. In examining how TPC practices marginalize people with disabilities, Jason Palmeri (2006) discusses how “technical communication participates in the discursive process of normalization: legitimating and subjugating knowledges, examining and controlling workplace practices, forming subjectivities, and marking bodies as normal or deviant” (p. 49). Bennett (2022) calls on those in TPC to consider documents’ sociopolitical implications through ableist studies and disability justice, highlighting the problematic individualized view of disability that puts the onus on each worker to conform to a standard workplace. Such an attitude prevents systemic changes that could lead to more equitable conditions.

Workplace lactation requires rethinking spaces, and Dolmage’s (2017) idea of “the retrofit” explains how ableist framing of spatial accommodations marginalizes people. He uses this metaphor to demonstrate how accommodations in higher education are often inadequate and emblematic of larger systemic problems since they attempt to “‘fix’ spaces” that have not been constructed for a variety of bodies. He argues, “retrofits are not designed for people to live and thrive with a disability, but rather to temporarily make the disability go away.” He points out how these accommodations—in an attempt to address structural ableism—end up “accentuat[ing] and invit[ing] disablism” when individuals must single themselves out, taking on risk due to the power imbalance associated with asking for assistance (p. 70). Such issues play out under current governance of workplace lactation as individuals approach supervisors and navigate traditional spaces and expectations.

Roles of Feminist Scholarship

When applied to documents governing workplace lactation, feminist scholarship—both directly and indirectly related to lactation practices—helps lead TPC scholars and practitioners toward interventions by uncovering hidden values that marginalize women. Peterson and Walton (2018) call on researchers to employ feminist methods to draw attention to silences, absences, and delegitimized expertise in an effort to correct injustices (p. 425). Koerber (2006b) has examined how privileging medical expertise has devalued women’s knowledge, despite Wylie’s (2004) concept of inversion thesis that suggests how women’s experiences make them “epistemically privileged in some crucial respects” (Peterson & Walton, 2018, p. 424). In this case, teacher-mothers have invaluable, untapped tacit knowledge.

Further, Koerber (2005) describes how medical discourse favors regularity, consistency, and ideas of “normal” inherently at odds with women’s bodies, which are marked by fluctuation, changes, and variations deemed “irregular or abnormal” when judged by these standards (p. 309). Legal systems’ and industries’ use of medical knowledge as the epistemological basis for law and policy, compounded by an ethic of expediency prioritizing financial gain, further devalues individuals’ experiential knowledge. In their study of how institutional documents lead to trans oppression in shelters, Moeggenberg et al. (2022) note, “Through their erasure of difference and … singular focus on efficiency and expediency (Frost, 2016), technical communication genres can unwittingly reflect dominant ideologies through supporting neoliberal agendas (Harvey, 2007)” (p. 407). Laws and HR guidance are similarly informed by rigid conceptions of norms and privilege workplace authorities’ judgment and priorities.

If the ultimate goal is creating more inclusive workplaces that are set up ideologically, systemically, and spatially to support women, employing Frost’s (2016) apparent feminism offers ways to intervene because it stresses “being explicit about feminist identity in response to socially unjust situations,” (p. 407) making it well-suited to address workplace lactation—an issue long-relegated to the private sphere that receives pushback in public spaces. Public attention is currently focused on teacher shortages and working conditions, creating an opportune moment to make visible the difficulties teacher-mothers experience and gather allies outside of those who identify as feminists.

Peterson and Walton (2018) encourage TCs to address “gendered challenges” (p. 420). My methods are limited to analyzing discourse affecting all people who lactate, but I encourage readers to keep in mind the variety of bodies in workplaces. Research with different methods could better focus on the experiences of those who are most vulnerable such as BIPOC and trans or non-binary people.

Methodology

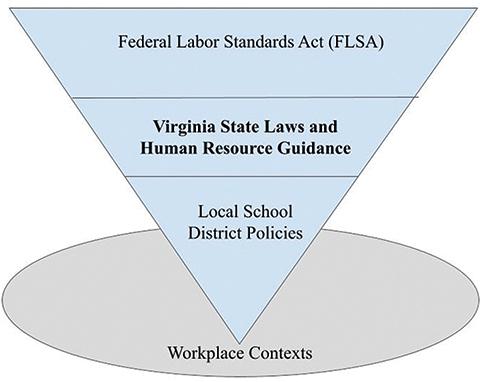

Virginia public schools serve as a model of many workplaces that are governed by layers of hierarchical laws, guidance, policies, and local contexts where implementation occurs. Since these are highly connected, I draw on Fairclough’s (1992) three-dimensional view of critical discourse analysis, which emphasizes intertextuality and focuses on analysis of context, text production and interpretation, and the text itself. This approach is relevant due to the intertextual relationships between the three levels of hierarchical text involved in governing workplace responses to lactating teachers—federal, state, and local school districts—but CDA also aids in unearthing the values, ideologies, and power dynamics inherent in these documents and how they are implemented in local contexts. Walwema and Carmichael (2021) employ this approach to study U.S. labor and immigration laws’ relationship to hiring documents, highlighting the rhetoric’s ecological nature and exposing how language can exclude.

Data Collection

To develop my dataset, I first searched for Virginia law related to workplace lactation and guidance from the state’s human resources department concerned with implementing workplace lactation. Three codes and a policy document were most relevant to this study’s scope and goals:

- §2.2-3909, “Causes of action for failure to provide reasonable accommodation for known limitations related to pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions,” is part of the Virginia Human Rights Act passed in July 2020, and lays out what is required of employers.

- §22.1-79.6, “Employee lactation support policy,” effective 2014, mandates each local school district create its own policy.

- §2.2-1201.14b, “Duties of Department; Director,” states Virginia’s HR director shall develop personnel policies related to break time for nursing mothers and lays out stipulations for these policies.

- Virginia State Human Resources Department’s (VDHR) website offers a document, “Breaks for Nursing Mothers–Resource Guide,” published in 2019 to provide more guidance for employers than the law supplies with a question and answer format.

These documents are the second layer of a hierarchy of documentation (See Figure 1). To understand how they relate to the top and bottom of the hierarchy, I compared them to the Federal Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and local policies from 10 school districts, representing each of Virginia’s Department of Education’s (VDOE) eight superintendent regions.

Data Analysis

I employed three stages of analysis to provide an ecological perspective. First, I examined the FLSA’s language in order to code state language that repeats federal law and determine how state laws and guidance echo and/or differ from federal standards. To study the implementation of code §22.1-79.6, which requires school districts to create a lactation policy, I examined 10 local policies. Eight of these were remarkably brief and simply repeated state language.

In the second stage, I analyzed the three Virginia legal codes, HR resource guide, and district policies according to the tenets of CDA (Johnstone, 2008). Drawing on Jones et al.’s (2016) positionality, power, and privilege, I considered how their language positions employers and employees in addition to coding wording choices and the documents’ epistemological underpinnings. I made three passes of the data, refining my codes each time. Segments were almost always one sentence or shorter, and I employed simultaneous coding when one sentence or phrase surfaced more than one code.

Analyzing three hierarchical levels of texts assisted in understanding how local contexts are ultimately governed, but to better consider implementational complexity, in the last phase of analysis, I considered how references to time and space—two prominent codes that emerged—relate to current workplace contexts in Virginia public school buildings. Consulting information from the VDOE and National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) afforded a view of current challenges in worksites.

Findings

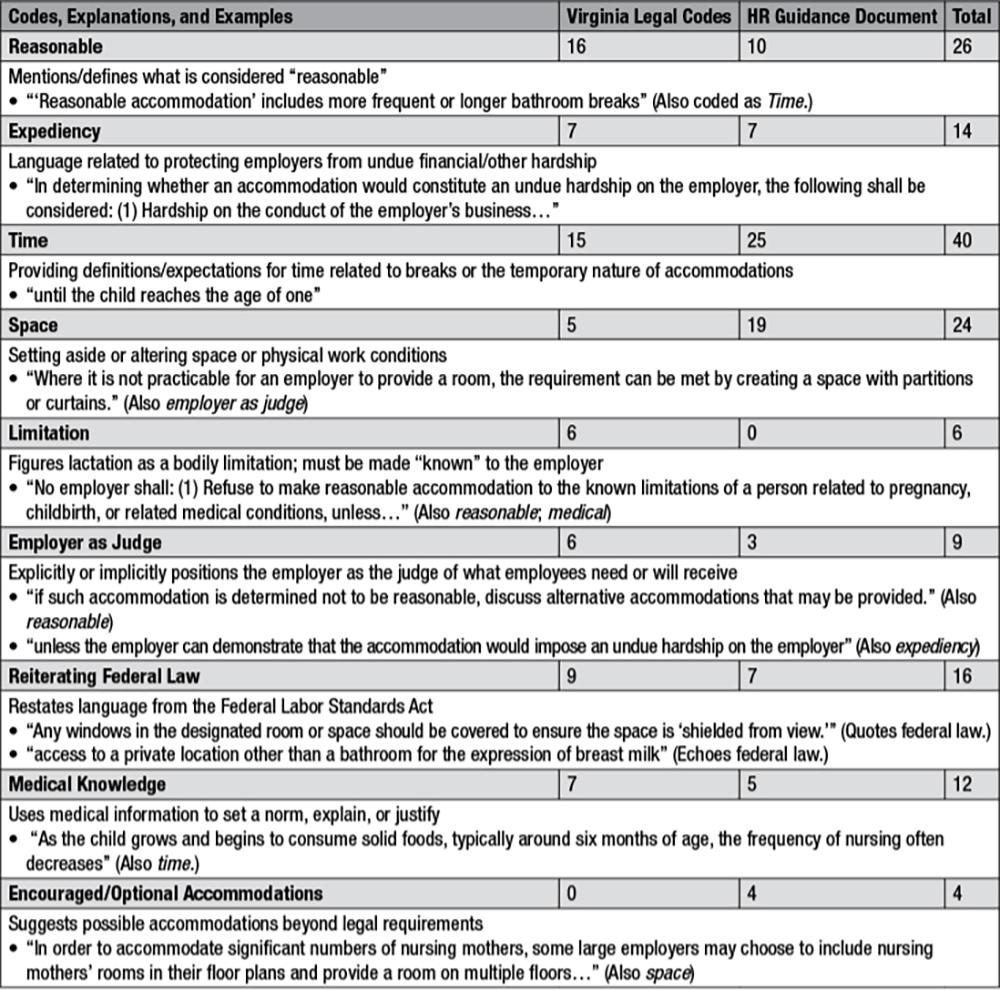

CDA of the three Virginia legal codes and the HR guidance document yielded patterns demonstrating epistemological underpinnings, values, and positioning of employers and employees (See Table 1).

Since the documents discuss when and where breaks will occur, the codes time and space were frequent, with 40 instances of time. Though related, I limited time to practical matters of application that create boundaries regarding when workers may take breaks and for how long and identified expediency as language related to protecting employers from undue financial or other hardships, which occurred 14 times. Language explaining how to handle space and physical work conditions occurred 19 times in the HR guidance document since it clarifies what is and is not required for employers in a variety of work environments. The guidance document presents four occurrences of encouraged/optional accommodations beyond legal requirements.

Reiterations of federal law appeared 16 times, demonstrating adherence to previous approaches from the top of the hierarchy. In total, 26 segments of text define and clarify what is reasonable, which is one way the documents echo legal language associated with disabilities in addition to the six times the legal codes figure lactation as a bodily limitation that must be made known to the employer. I found language positioning the employer as a judge nine times in the documents and language associated with medical knowledge, which sets a norm and/or explains or justifies, 12 times.

Discussion

Figuring Lactation as a Disability

Lactation occupies a complex position in the legal sphere, which defines it as a medical condition related to pregnancy and childbirth. Lactation is not accounted for in the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), but language associated with disability and a deficit conception of lactation are evident throughout these documents, which refer to employers’ “limitations” in the legal codes and center the notion of “reasonable accommodation.” Women’s bodies are still marginalized and viewed as problematic in the workplace—even where they occupy majority status as in the 76% female K–12 education field (NCES, 2018).

In alignment with Palmeri’s (2006) points about technical documents setting “norms” and defining deviant bodies, Virginia’s legal codes and HR guidance employ medical knowledge to set standards and expectations for what employers should consider “normal,” such as the guide’s answer to how long breaks should be, which explains, “the act of expressing breast milk alone typically takes about 15-20 minutes” (VDHR, p. 2). Many bodies do not conform to this timeline, which is associated with a high-quality double-pump, highlighting a possible socioeconomic inequity. People in high-stress jobs may find letdown (the release of milk) takes longer due to the relaxation it often requires. If individuals are dehydrated or spending meal breaks pumping, they will face further difficulty (La Leche League International, 2022). The guide next offers one of two considerations accounting for employees’ material conditions, mentioning other factors such as the length of time it may take to “walk”—note another normative assumption—to the lactation space, fetch their pump from its stored location, or access a sink (VDHR, p. 2).

These are vital concerns, and the document cites the Department of Labor’s consideration of all “steps reasonably necessary” when assessing the reasonableness of break time; however, these ideas are complicated when the document states workers do not need to be compensated for break time unless it coincides “with other breaks considered to be work hours and last[s] for 20 minutes or less.” Additional material conditions are overshadowed by this language: “If the employee uses significant additional time, the employer should permit the employee to adjust her [sic] schedule to make up the time, charge appropriate leave time as necessary, or to be docked for that additional time” (VDHR, p. 4). This sets up the employee to possibly attempt to rush the process, which could result in getting an infection or contamination, taking a financial penalty, resigning, or deciding breastfeeding is not possible if they cannot fit the norm presented.

Bennett (2022) examines various warrants related to disability such as the notion of “bodymind as able,” exposing how such assumptions “perpetuate problematic understandings of disability as a personal issue” and allow employers to create “individual accommodations to align individuals with a standard work environment, rather than environmental changes to include … individuals as they are” (p. 232). The guidance document contains five questions about lactation space, which emphasize worries about a lack of resources to accommodate lactating employees. Answers reassure employers they are “not obligated to maintain a permanent, dedicated space for nursing mothers” (VDHR, p. 2). Rather than having a visible, dedicated space, the document repeatedly informs employers of just how little they need to do. For example, where no room is available, they can “creat[e] a space with partitions or curtains,” and they do not have to provide refrigeration but must allow workers to bring their own cold storage (VDHR, p. 3).

Dolmage’s (2017) notion of retrofitting is key to current workplace lactation approaches. Since the ADA passed in 1990, the public has begun to understand disability in terms of space, yet he notes temporary accommodations are based on a “compliance” orientation toward disability that allows access but precludes “the possibility of action for change” (p. 77). Accommodations that are temporary after-thoughts preserve traditional notions of the workplace as a space designed for non-disabled, masculine bodies. Imagine schools where lactation spaces were permanent, visible fixtures women could count on without special accommodation when planning a family.

“Accommodation” is also a key concept in David Dobrin’s (1983) definition of technical communication as “writing that accommodates technology to the user,” which scholars have challenged (p. 227). Scott (2018) asserts, “Rather than asking how we can accommodate users,” TCs should “ask how we can responsively redress those users who are marginalized by technical communication through the redistribution of resources (technological, rhetorical, and otherwise)” (p. 306). In underfunded workplaces, this orientation opens up possibilities for both how TCs might rethink the process of writing policy to make it more human-centered and participatory and consider how to reallocate resources to meet the needs of the people policies affect, in addition to the community impacted when employees resign.

Ethic of Expediency

Increasing expenditures heighten institutions’ anxiety, and employers may see the law as an unfunded mandate. The state attempts to reassure employers by emphasizing an ethic of expediency. In addition to stressing the bare minimum for compliance, the guidance document lists accommodations that can be made such as adding a lactation room to the floor plan if there are many people to accommodate, providing refrigeration, “ideally” having electricity to run a pump, and having a sink nearby for the employee to wash their hands and pump equipment. It states, “While such additional features are not required, providing such spaces may decrease the amount of break time needed,” emphasizing the reason for including them would be to increase work time, rather than considering human needs, and framing accommodations as creature comforts rather than ways to facilitate health, reduce stress, and support employees as humans (VDHR, p. 3). Such an attitude is reminiscent of Steven Katz’s (1992) point that “[i]n a capitalistic society, technological expediency often takes precedence over human convenience, and sometimes even human life” (p. 207).

While code §2.2-3909 states employers cannot refuse “reasonable accommodation” for lactating employees, they do not have to make an accommodation if they can demonstrate it “would pose an undue hardship” on the employer, which would only be necessary to prove if the employee pursued legal action. The definition of “undue hardship” includes:

- Hardship on the conduct of the employer’s business, considering the nature of the employer’s operation, including composition and structure of the employer’s workforce;

- The size of the facility where employment occurs; and

- The nature and cost of the accommodations needed. (VHRA, B.1)

The language is concerned with the employer’s ability to remain productive and avoid financial strain and is sufficiently vague, so it is unclear what constitutes a cost that would preclude the accommodation. Such uncertainty may dissuade an employee from pursuing legal action.

Katz (1992) explains when we are overly concerned with the “‘efficient’ operation” of a system, we can fail “the people the system is supposed to serve.” State documents governing and guiding workplace lactation reiterate and reinforce federal law, attempt to mitigate financial worries, and emphasize minimal accommodations, echoing Katz’s point that “[i]n any highly bureaucratic, technological, capitalistic society, it is often the human being who must adapt to the system” (p. 207). The capitalistic underpinnings of the documents position women as secondary to the financial impacts on the organization’s ability to conduct business as usual.

Employer as Judge

Katz (1992) also extends his argument to how technical communication governs deliberative discourse about “what should or should not be done,” tending to base decisions on expediency (p. 200). Legal code §2.2-3909 offers this language that sets the stage for deliberative discourse:

Each employer shall engage in a timely, good faith interactive process with an employee who has requested an accommodation pursuant to this section to determine if the requested accommodation is reasonable and, if such accommodation is determined not to be reasonable, discuss alternative accommodations that may be provided. (VHRA, C)

The employer’s communication is required to be “timely,” in “good faith,” and “interactive,” suggesting a discursive process with a back-and-forth. Yet, the second half of the sentence reveals the purpose is for the employer to judge the reasonableness of any requested accommodation. As Katz reminds us, the ethic of expediency underlying “deliberative rhetoric can be made to serve exclusively the technological interests of “the State” (p. 207). The documents figure the employer not as a supportive colleague but as the guardian of the organization’s resources.

The guidance document establishes norms from which employers can make decisions about individuals, leaving those individuals’ input potentially undervalued. The basic nature of medical knowledge the documents reference indicates the audience, employers who assess what is reasonable, includes those with little to no familiarity with women’s bodies. For this and other reasons—their relationship with the supervisor, embarrassment, desire to be a “good worker”—women may not approach their supervisors. Similarly, Dolmage (2017) notes the ADA places the responsibility on the individual seeking accommodations, “admitting that dominant pedagogies privilege those who can most easily ignore their bodies” (p. 80).

Jones et al.’s (2016) positionality, privilege, and power concepts that “impact social capital and agency” in their framework for more inclusive TPC research, remind us to consider the context of these discussions (p. 220), which require lactating employees discuss an intimate aspect of their bodies in the workplace with someone in a position of power. Though 76% of 3.5 million K–12 teachers are female, as of 2020, a mere 27% of superintendents were female (AASA, 2020). Of 10 school district policies, six make the superintendent responsible for the lactation space. The gender disparity may contribute to power imbalances and a possible lack of understanding of the material and embodied realities employees face.

Additionally, Jones et al. (2016) remind us of intersectional considerations and how multiply-marginalized individuals encounter compounded difficulties. In 2018, 79% of teachers identified as white (NCES, 2021). The odds are that BIPOC employees will be having these conversations with white supervisors, exacerbating problematic power dynamics. Harper (2020) uncovers how the “welfare queen” trope positions Black mothers as opportunistic or criminal for seeking the same advantages as white mothers. Moeggenberg et al. (2022) examine the problematic nature of “good faith” in documents that allow discrimination against trans individuals, asserting they align “‘good faith belief’ with scrutinization of another’s body” to determine their fate (p. 421). In code §2.2-3909, employees are subject to their supervisor’s judgment of whether their bodily needs are reasonable, regardless of biases or lactation knowledge.

With disabilities, once an attempt at accommodation has been made, Dolmage (2017) explains there is typically no “feedback loop;” instead, the individual seeking accommodations is supposed to be “thankful” regardless of the accommodation’s efficacy (p. 81). Similarly, the code’s framework for the process closes after any accommodation decision, regardless of efficacy.

Passing Power Down the Hierarchy

Fairclough (1992) calls texts “sensitive barometers of social processes,” asserting intertextual analysis can indicate social and cultural change (p. 211). The Department of Labor states, “The FLSA does not preempt State or local laws that provide greater protections to employers (Fact Sheet #73, para. 4). This language passes power to the state level, opening the door for further support, and while it sounds promising, the state law—though it requires break time for workers who are exempt from the FLSA—in large part simply reiterates the federal language. It also requires local school districts to develop policies of their own, but a sample of those policies demonstrates how few districts take concerted action beyond state requirements, missing opportunities to use local knowledge and teacher input in the policy design process. This example is similar to eight of the 10 policies that are one-two sentences and reiterate state language:

The Superintendent shall designate a non-restroom location in each school as an area in which any mother who is employed by the County … may take breaks of reasonable length during the school day to express milk to feed her [sic] child until the child reaches the age of one. The area must be shielded from public view. (Frederick County Public Schools)

When the policy and guidance are sparse and merely reiterative, public school administrators must negotiate supporting employees in their particular contexts on their own. As an exception to these anemic policies, Fairfax County’s comparatively robust policy contains words like “support” and “collaborate” and references a lactation support program. This is one of the wealthiest districts in the state, but it may serve as a model.

Space, Time, and the Nature of the Job

All three levels setting law and policy mandate a space that is not a bathroom, which is “shielded from view,” “private,” or “free from intrusion from coworkers and the public,” depending on the document. The HR guidance document addresses some difficulties with providing space in localities when it suggests using partitions or curtains and achieving privacy “through means such as signs that designate when the space is in use, or a lock on the door” (p. 3). In schools, curtains and a sign will not guarantee privacy in an environment where children, some of whom cannot read, are present.

Spatial concerns are exacerbated in overcrowded workplaces with shared space. Virginia schools highlight these problems since 40.5% of buildings are currently at or above capacity and 29.4% more are nearing capacity (Dickey & Ramnarain, 2021, slide 7). Over half of schools are more than 50 years old, and only 78% comply with the ADA (slides 8, 13). Although some newer buildings may have been designed with lactation spaces, this is not a current requirement, so most are subject to retrofitting.

Even when buildings have a dedicated lactation space, without organizational support, it may not be effective. Porter and Oliver (2016) examine how a program that set aside lactation spaces at Virginia Tech missed opportunities to create larger discussions about gender equity since space alone is not sufficient to create a supportive climate at work without “a continued conversation” among the workplace community (p. 82). They warn ensuring privacy and seclusion alone risks “closet[ing] lactation as a female-body specific act to maintain the universal disembodied individual” (p. 88). Individuals facing lactation issues must not be expected to take on the additional burden of the public conversations required to fully include them in the workplace to achieve gender equity. We need apparent feminism here—the support of others, especially those who have not experienced lactation—to help create these conversations.

Where time is concerned, though law and guidance reiterate that employers must allow break time, neither federal nor Virginia state law requires compensation. Lucas and McCarter-Spaulding’s (2012) examination of factors impacting breastfeeding and employment reveals “often policy solutions and supportive workplaces assist those already privileged,” and differences often intersect “with socially constructed class and race identities” (pp. 154, 144). For example, in the United States, Black women are less likely to breastfeed, and higher socioeconomic status is associated with longer breastfeeding rates, regardless of race. BIPOC women are underrepresented in careers where they may have space and time to express milk, and in teaching, they are more likely to face greater complexity in approaching supervisors for accommodations. Longer maternity leave is associated with longer breastfeeding, and returning to work “decreases breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity” (p. 145). Most teachers needing to maintain their income must return to work six weeks postpartum, increasing the need for lactation support at work if they intend to breastfeed. Policy application impacts individuals differently, creating ample opportunity to perpetuate systemic injustice and potential bias in one-on-one interactions between teachers and supervisors.

The very nature of the job further complicates break time since taking at least 20 minutes every three hours to pump is challenging without supportive supervisors and colleagues. Considering the career centers around caring for and instructing minors who cannot be left unattended, break time requires cooperative planning. Spitzmueller et al. (2018) find jobs with high workloads and requiring “mothers to be consistently and continuously mentally engaged in their work” make pumping difficult. They note highly regimented work schedules may offer well-spaced breaks conducive to pumping (p. 466). Teaching’s workload often exceeds contract hours and requires constant mental engagement as teachers respond to individuals and re-plan on the fly to meet the group’s needs. The schedule, while highly regimented, has few breaks, which are not necessarily evenly spaced. Elementary school teachers may only have one break during the day when students attend art, music, or P.E.

Hiring a floating substitute to cover classes is a useful strategy, which can help any employee who has an unplanned absence or needs to take a half-day to tend to a sick child, but it’s an added cost, and it may be difficult to maintain given shortages: at the start of the 2022–2023 school year, almost half of districts reported unfilled teaching jobs (St. George, 2022). Resignations were responsible for 51% of teacher vacancies, and substitute positions have become harder to fill (IES, 2022). It has become common for teachers to cover each other’s classes, often without additional compensation, which positions lactating teachers as indebted, having infringed on another’s planning time. Recent public attention on shortages makes conditions ripe for increasing support for teacher well-being initiatives.

Conclusion and Implications

While the state has sanctioned an opportunity for school districts to offer further support through localized policies, districts tend to merely adopt the state’s ethos and language, continuing to figure lactation as a disability, maintain the ethic of expediency, and ignore women’s knowledge and material conditions. Studying how teachers have managed to make pumping work and how they struggled would offer institutions key information to better support women even in challenging contexts. In her study of Florida school district policies, Phillips (2020) finds private space, ample time, and supportive administrators and colleagues resulted in better teacher experiences. She recommends each school have its own policy to “fill the gap” left open by larger district and state policies and “reevaluate” them to ensure they “create a work environment that focuses on the teacher” (p. 110). While I agree, it is important to consider how leaving so much decision-making up to the individual site is a double-edged sword since local realities may require flexibility to meet women’s needs, but federal and state language and guidance mandating supportive climates and attitudes would make support the expectation rather than the luck of the draw.

Yet, history shows waiting for larger systemic changes will leave women right where they are. In December 2010, the Department of Labor sought public input about the March 2010 Reasonable Break Time amendment to the FLSA because of requests for additional guidance, but determined “regulations may not be the most useful or effective means for providing initial guidance to employers and employees,” citing “the variety of workplace environments, work schedules, and individual factors that will impact the number and length of breaks required by a nursing mother, as well as the manner in which an employer complies with break time requirement” (para. 5). To date, no additional regulations have been instituted.

TCs need not wait for federal action to articulate local policies utilizing women’s knowledge of material conditions in their buildings and their actual physical needs. Disappointed with the medical community’s lack of information on exclusive pumping, McCaughey (2021) coins the term tactical motherhood, citing Holladay (2017), who suggests “‘official’ documents be reconsidered or rewritten to reflect the kinds of knowledge (and tactics)” women offer (pp. 34, 44). Further research gathering teacher-mothers’ experiential knowledge will benefit policy-makers and is something I intend to pursue. As Jones and Williams (2022) suggest, scholars and TCs can learn from questioning and seeking out what is missing from technical documents. In many cases, participatory, human-centered design involving end-users at all phases of the design process and taking material conditions into account can begin to fill in those blanks. McKinley Green (2020) notes expanding our understanding of people beyond “their efficient and productive use” illuminates them as “individuals who navigate identities, commitments, and public beyond and apart from their interaction with technologies” (p. 333).

Workplace lactation documents in Virginia schools serve as a case study TCs can use to begin to question and discuss how epistemological and ethical bases of policies and guidance affect workers in local contexts. Further, rethinking a deficit orientation toward lactation that figures it as requiring temporary accommodation would pave the way for changes in spaces that can benefit all. At the local level where policies are implemented, in addition to seeking employee input, TCs can consider how to make lactation spaces permanent, visible fixtures; how work coverage can be at-the-ready; and/or how requirements can be implemented to ensure supervisors and others are educated on lactation support to begin to change local conditions and even set an example for the state and federal levels. To garner support from stakeholders, TCs can draw on apparent feminism by citing worker shortages and encouraging employees to share experiences to demonstrate the consequences of relying on existing policy and guidance alone, which leaves critical fields like teaching and nursing especially vulnerable without intervention.

References

AASA (2020, February 10). AASA releases key findings from American Superintendent 2020 Decennial Study. AASA. https://www.aasa.org/content.aspx?id=44397

Agboka, G. Y., & Dorpenyo, I. K. (2022). Curricular efforts in technical communication after the social justice turn. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 36(1), 38–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/10506519211044195

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2022, June 27). American Academy of Pediatrics calls for more support for breastfeeding mothers within updated policy recommendations [Press release]. https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2022/american-academy-of-pediatrics-calls-for-more-support-for-breastfeeding-mothers-within-updated-policy-recommendations/#:~:text=AAP%20recommends%20that%20birth%20hospitals,years%20especially%20in%20the%20mother.

Frost, E. (2016). Apparent feminism as a methodology for technical communication and rhetoric. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 30, 3–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/10506519156022

Frost, E. (2018). Apparent feminism and risk communication. In M. F. Eble & A. M. Haas (Eds.), Key theoretical frameworks: Teaching technical communication in the twenty-first century (pp. 23–45). Utah State University Press.

Bennett, K. C. (2022). Prioritizing access as a social justice concern: Advocating for ableism studies and disability justice in technical and professional communication. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 65(1), 226–240. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2022.3140570

Colton, J. S., & Holmes, S. (2018). A social justice theory of active equality for technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 48(1), 4–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616647803

Dickey, K., & Ramnarain, V. (2021). Needs and conditions of Virginia public school buildings and Virginia’s school facilities guidelines: Presentation to the board [PowerPoint slides]. Virginia Department of Education.

Dobrin, D. (1984). What’s technical about technical writing? In New essays in technical and scientific communication: Research, theory, practice. P. Anderson, J. R. Brockman, & C. R. Miller (Eds). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315224060

Dolmage, J. (2017). Academic ableism: Disability and higher education. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9708722

Duties of Department, Director, § 2.2-1201.14b. https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title2.2/chapter12/section2.2-1201/

Durack, K. (1997). Gender, technology, and the history of technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 6(3), 249–260. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427625tcq0603_2

Employee Lactation Support Policy, § 22.1-79.6. https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title22.1/chapter7/section22.1-79.6/

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and text: Linguistic and intertextual analysis within discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 3(2), 193–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926592003002004

Fairfax County School Board. (2016). Policy 4425 duties, responsibilities, and rights of employees’ lactation support programming. https://go.boarddocs.com/vsba/fairfax/Board.nsf/files/AE3GPX44D484/$file/P4425.pdf

Frederick County School Board. (2014). 569P – Lactation support. https://www.frederickcountyschoolsva.net/site/default.aspx?PageType=2&PageModuleInstanceID=5604&ViewID=1c43854f-5875-4d47-be5f-0e18028c22cb&FlexDataID=12441

Green, M. (2020). Resistance as participation: Queer theory’s applications for HIV health technology design. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(4), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2020.1831615

Harper, K. C. (2022). The ethos of Black motherhood in America: Only white women get pregnant. Lexington Books.

Hausman, B. (2000). Rational management: Medical authority and ideological conflict in Ruth Lawrence’s Breastfeeding: A guide for the medical profession. Technical Communication Quarterly, 9(3), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572250009364700

Hausman, B. (2012). Chapter 1. Feminism and breastfeeding: Rhetoric, ideology, and the material realities of women’s lives. In P. Smith, B. Hausman, & M. Labbok (Eds.), Beyond health, beyond choice: Breastfeeding constraints and realities (pp. 15–24). Rutgers University Press.

Hausman, B., Smith, P., & Labbok, M. (2012). Introduction. In P. Smith, B. Hausman, & M. Labbok (Eds.), Beyond health, beyond choice: Breastfeeding constraints and realities (pp. 1–12). Rutgers University Press.

Johnstone, B. (2008). Discourse and world. Discourse analysis (2nd ed.). Blackwell.

Jones, N., & Williams, M. F. (2017). The social justice impact of plain language: A critical approach to plain-language analysis. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 60(4), 412–429. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2017.2762964

Jones, N., & Williams, M. F. (2022). Archives, rhetorical absence, and critical imagination: Examining Black women’s mental health narratives at Virginia’s Central State Hospital, IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 65(1), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2022.3140883.

Jones, N., Moore, K. R., & Walton, R. (2016). Disrupting the past to disrupt the future: An antenarrative of technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 25(4), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2016.1224655

Katz, S. B. (2004). The ethic of expediency: Classical rhetoric, technology, and the Holocaust. In Johnson-Eilola & Selber (Eds.), Central works in technical communication (pp. 35–43). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1992)

Koerber, A. (2005). You just don’t see enough normal: Critical perspectives on infant-feeding discourse and practice. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 19(3), 304–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651905275635

Koerber, A. (2006a). From folklore to fact: The rhetorical history of breastfeeding and immunity, 1950-1997. The Journal of Medical Humanities, 27(3), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-006-9015-8

Koerber, A. (2006b). Rhetorical agency, resistance, and the disciplinary rhetorics of breastfeeding. Technical Communication Quarterly, 15(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427625tcq1501_7

La Leche League International. (2022). Pumping milk. LLLI. https://www.llli.org/breastfeeding-info/pumping-milk/

Lucas, J., & McCarter-Spaulding, D. (2012). Chapter 12. Working out work: Race, employment, and public policy. In P. Smith, B. Hausman, & M. Labbok (Eds.), Beyond health, beyond choice: Breastfeeding constraints and realities (pp. 144–156). Rutgers University Press.

McCaughey, J. (2021). The rhetoric of online exclusive pumping communities: Tactical technical communication as eschewing judgment. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2020.1823485

Moeggenberg, Z. C., Edenfield, A. C., & Holmes, S. (2022). Trans oppression through technical rhetorics: A queer phenomenological analysis of institutional documents. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 36(4), 403–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/10506519221105492

NCES: National Center for Education Statistics. (2021). Characteristics of public school teachers. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/clr

NCSL: National Conference of State Legislatures. (2021, August 26). Breastfeeding state laws. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/breastfeeding-state-laws.aspx

Palmeri, J. (2006). Disability studies, cultural analysis, and the critical practice of technical communication pedagogy. Technical Communication Quarterly, 15(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427625tcq1501_5

Petersen, E. J., & Walton, R. (2018). Bridging analysis and action: How feminist scholarship can inform the social justice turn. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 32(4), 416–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/10506519187801

Phillips, M. M. (2020). K–12 teachers’ experiences “With or without” Breastfeeding/Pumping policy in the school workplace (Order No. 28025876). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2437187762). http://mutex.gmu.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/k-12-teachers-experiences-with-without/docview/2437187762/se-2

Porter, J., & Oliver, R. (2016). Rethinking lactation space: Working mothers, working bodies, and the politics of inclusion. Space and Culture, 19(1), 80–93.

Reasonable break time for nursing mothers, Department of Labor, 75, 244 Fed Reg. 80073 (December 21, 2010). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2010-12-21/html/2010-31959.htm

Rose, E. (2016). Design as advocacy: Using a human-centered approach to investigate the needs of vulnerable populations. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(4), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616653494

Scott, J. B. (2018). Afterword: From accommodation to transformation. In M. F. Eble & A. M. Haas (Eds.), Key theoretical frameworks: Teaching technical communication in the twenty-first century (pp. 23–45). Utah State University Press.

Sims, M. (2022). Tools for overcoming oppression: Plain language and human-centered design for Social Justice. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 65(1), 11–33. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2022.3150236

Spitzmueller, Zhang, J., Thomas, C. L., Wang, Z., Fisher, G. G., Matthews, R. A., & Strathearn, L. (2018). Identifying job characteristics related to employed women’s breastfeeding behaviors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(4), 457–470. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000119

U.S. Department of Labor. (2010, March 23). Section 7(r) of the Fair Labor Standards Act – Break time for nursing mothers provision. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/nursing-mothers/law

U.S. Department of Labor. (2023). Fact sheet #73: FLSA protections for employees to pump breast milk at work. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fact-sheets/73-flsa-break-time-nursing-mothers

Virginia Department of Human Resources. (2019). Breaks for nursing mothers – Resource guide. https://www.dhrm.virginia.gov/docs/default-source/hrpolicy/policyguides/breaks-for-nursing-mothers—resource-guide-5-15-19.pdf?sfvrsn=0

Virginia Human Rights Act, Chapter 39, § 2.2-3900. https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacodefull/title2.2/chapter39/

Walwema, J., & Carmichael, A. F. (2021). “Are you authorized to work in the U.S.?” Investigating “inclusive” practices in rhetoric and technical communication job descriptions. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(2), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2020.1829072

About the Author

Danielle De Arment-Donohue is a Writing and Rhetoric PhD student at George Mason University and an assistant professor of English at Laurel Ridge Community College. One of her research interests is the concept of transfer in composition pedagogy. She also researches rhetoric related to the feminization of teaching, teacher well-being, and workplace lactation experiences. She hopes her research contributions in these areas lead to more equitable working conditions in education that consider employees’ lived experiences. Her chapter, “Schooling the Public: Empathy in K-12 Teachers’ Social Media Posts during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” will appear in the forthcoming edited collection, Through Lines: Meditations on Academic Labor, Gender, and Lessons of the Long 2020, published by University of South Carolina Press. Danielle holds master’s degrees from George Mason University and the University of Virginia and is a National Board Certified Teacher. She began her career as a high school English teacher and has taught composition at Northern Virginia Community College and Shenandoah University. Danielle De Arment-Donohue can be reached at ddearmen@gmu.edu.