Abstract

Purpose: Research shows that Western and Chinese technical communicators structure their documents in different ways. The research reported in this article is a first attempt to systematically explore the effects cultural adaptations of user instructions have on users. Specifically, we investigate whether Western (from Europe and North America) and Chinese (from the People’s Republic of China) users would benefit from a document structure that is theoretically assumed to reflect their cultural preferences.

Method: Using the SDL Trados Studio 2014 translation software package, a 2×2 experiment (N=80) was conducted with manual structure (Western versus Chinese) and cultural background (Western versus Chinese) as independent variables. The Chinese and Western manual structures were based on the literature on cultural differences between Western and Chinese technical communication. Dependent variables were task performance, knowledge, and appreciation of the software and the user instructions.

Results: Contrary to our expectations, no significant differences were found between the conditions. Both Western and Chinese participants performed equally well and were equally appreciative when using the Western and Chinese manual structure.

Conclusion: The results of our study raise questions about the validity and/or the relevance of the current insights regarding cultural differences in the structures of user instructions. Cultural differences found in content analytic research may reflect the habits of technical communicators rather than the preferences of users. However, caution is needed in interpreting our findings, as our research experiences also raised a number of methodological issues that must be addressed in future research.

Keywords:intercultural communication, cross-cultural communication, Chinese culture, user instructions, user manual, structure

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Cross-cultural research is not only useful for gearing user documentation to international user groups, but also gives us the opportunity to reflect on current practices in Western technical communication.

- A first comparison with Western and Chinese participants shows that cultural adaptations of the structure of user instructions do not seem to matter.

- More empirical research is needed involving a user perspective on cultural differences; content analyses of current practices in technical communication may not be very informative about user needs and preferences.

Introduction

As a result of the rapid developments in information and communication technology (ICT) and transportation in the past decades, the world has truly developed into a “global village,” such as that predicted by McLuhan (1962). The world has become smaller and smaller, communication around the globe has intensified, and markets are developing into global markets. Cross-cultural and intercultural communication have become increasingly important, not only because of the globalization and internationalization trends, but also because there is a lot of cultural diversity within our national boundaries.

Of all communication sub disciplines, technical communication may have the strongest need to develop an international and intercultural orientation, as technology does not stop at the border. International collaborations and international markets are increasingly important. As a consequence, we can see a growing interest, both in practice and in the literature, in the (related) issues of translation (for example, Lentz & Hulst, 2000; Maylath, 2013; Maylath, Vandepitte, Minacori, Isohella, Mousten, & Humbley, 2013), localization (for example, Agboka, 2013; Chao, Singh, Hsu, Chen, & Chao, 2012; St. Germaine-Madison, 2009; Zhu & St.Amant, 2010), and cultural differences (for example, Barnum & Li, 2006; Hall, De Jong, & Steehouder, 2004; McCool & St.Amant, 2009).

Despite the practical importance of intercultural and cross-cultural communication and the increased research interest for the topic, our knowledge regarding the role of cultural differences in technical communication is still limited and fragmented. Several factors may play a role at this point. First, the field of intercultural and cross-cultural communication is very broad: So many cultures, with variations on so many different aspects, may be compared to each other. Second, the possible research approaches vary. For instance, some studies take an emic perspective and try to understand a culture from within (for example, Yu, 2009), while others take an etic perspective and try to compare different cultures more objectively, from an outsider’s perspective (for example, Barnum & Li, 2006). Some studies focus on cultural differences that are manifest in documents; others focus predominantly on differences in users’ needs, preferences, and behaviors. Third, the research is methodologically complex, as language and translation issues must be taken into account and culture itself may affect the data collected (Hall, De Jong, & Steehouder, 2004; Peng, Nisbett, & Wong, 1997). Fourth, there is no conclusive theoretical framework to systematically investigate cultural differences. Top-down initiatives, such as Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010), as yet lack a convincing connection with the field of technical communication; bottom-up initiatives, such as Barnum and Li’s (2006) analysis of Chinese and Western documents, lack the comprehensive framework that would help us make sense of all differences.

In this article, we focus on cultural differences between Western countries and China. Those differences are particularly interesting because Chinese and Western cultures are the “most distant from one another and probably influenced one another the least” (Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001, p. 4). Indeed, several studies have indicated that there are differences within the domain of technical communication between China and Western countries (for example, Barnum & Li, 2006; Honold, 1999; Wang, Q., 2000; Wang, Y., & Wang, D., 2000).

It is important to realize, however, that differences between Chinese and Western technical communication may be attributed to several closely related factors, which cannot be isolated. One possible explanation involves the customs, needs, and preferences of users, which may reflect true cultural differences between China and the Western world. Another factor involves the writing habits that have developed independently of each other throughout the years. Yu (2009), for instance, shows that it is essential to know and understand the traditions of Chinese instructional texts to make sense of the current situation of technical communication in China. It would be too simple to assume a one directional relationship between the two factors: Writing habits may be based on assumptions about user preferences, but may shape user preferences at the same time. A third factor involves the different stages in the development of the field of technical communication: Technical communication and document design have a longstanding tradition in the Western world, but are only beginning to emerge in the Chinese context (Barnum, Philip, Reynolds, Shauf, & Thompson, 2001; Ding, D. D., 2011; Gao, Yu, & De Jong, 2013, 2014; Tegtmeier & Thompson, 1999). Of course, the developmental stage of technical communication is likely to affect the writing habits. Think of the developments in the Western world in the art of writing instructions in the past three decades (cf. Van der Meij, Karreman, & Steehouder, 2009).

At this stage, it would neither be justified to criticize technical communication in China using Western standards of high-quality technical communication, nor to assume that the current technical communication practices in China reflect optimal technical communication adapted to Chinese culture. In this constellation, content analyses of differences in documents may lead to ambiguous results, as they represent a mixture of anticipated user preferences, writing habits, and technical communication development. We would argue that user research is the key to an understanding of cultural differences between Western cultures and China, and is also the key to developing a technical communication body of knowledge within the Chinese context. For Western technical communication, such user research offers a mirror to reflect on the established technical communication principles that we may hold for universally true.

In this article we report on a first experimental study we conducted into the use and effects of culturally adapted user instructions by Western and Chinese participants. Western participants were defined as users from Europe and North America; Chinese participants were born and raised in the People’s Republic of China. In this study we focused on the structure of the user instructions. We designed two culture versions of user instructions, and compared how Western and Chinese participants reacted to and worked with them. Our hypothesis was that Western users benefit most from user instructions based on Western structuring principles, and Chinese users benefit most from user instructions based on Chinese structuring principles.

Before we describe the design and results of our study, we will first discuss the context of technical communication in China, the existing theories on cultural differences, and earlier research into Sino-Western cultural differences in technical communication.

Technical Communication in China

As a consequence of the fast economic growth of China and its gradual transition from a producing into a creative economy, technical communication as a profession and career opportunity is growing in China (Gao, Yu, & De Jong, 2013, 2014). Many large multinational companies, including Ericsson, Cisco, Motorola, Alcatel-Lucent, and Nokia Siemens, have set up their own specialized departments to develop technical documentation for the Chinese market. At the same time, originally Chinese companies such as Huawei, Haier, and Lenovo are rapidly expanding internationally, and thus need to be able to sell products as well as user support to foreign customers. The prospects for technical communicators in China are favorable.

However, the academic support for the profession is still lagging behind. Despite earlier attempts to introduce the American version of technical communication in China (Barnum et al., 2001; Tegtmeier & Thompson, 1999), and pioneering activities by U.S. based scholars (Ding, D. D., 2010; Ding, D. D., & Jablonski, 2001; Ding, H., 2010; Duan & Gu, 2005; Yu, 2010), comprehensive academic programs on technical communication are still not offered by Chinese universities, although there are some international collaborations with Western programs and several universities are now offering standalone technical writing or technical communication classes. From the available accounts of such courses, it becomes clear that they focus less strongly on competencies related to the technical communication body of knowledge (cf. Coppola, 2010) than on more or less general (English) language skills (Ding, D. D., 2010; Ding, D. D., & Jablonski, 2001, Ding, H., 2010; Duan & Gu, 2005). Some researchers even advocate integrating technical communication into English for Specific Purposes (ESP) (Duan & Gu, 2005; Hu, 2004) or English Related to Individual Disciplines (ERID) (Ding, H., 2010) programs.

Other researchers emphasize the strong traditional relationship, in the Chinese context, between technical translation and technical communication, and argue that technical communication could be further developed in close relation to translation programs (Miao & Gao, 2010; Wang, C., & Wang, D., 2011). Indeed, as argued by Maylath (2013), due to the rise of machine and computer-aided translation, the boundaries between technical translation and technical communication are gradually disappearing.

Despite various initiatives to promote and further technical communication in China, there is still much room for improvement. H. Ding (2010), for instance, argues that the quality of Chinese instructions produced, not to mention the English instructions, is unsatisfactory. Technical communication practitioners largely do not have a specialized education in technical communication, and have little or no access to formal training or meetings. The research that is necessary to support the academic development of the discipline is still in its infancy, and a professional association (parallel to STC) and an academic journal (like Technical Communication) are still missing. Therefore, “no specialized profession of technical communication exists” (Ding, H., 2010, p. 301).

Theories on Cultural Differences

Several general theories have been developed to make sense of cultural differences. French and Bell (1979) proposed the so-called Iceberg Model. According to this model, a culture consists of two interrelated parts: “a visible top that represents the facts, the technology, the price, the rationale behind things, the brain (and hands of an engineer), the written contract of a negotiation in an explicit way,” and “an invisible bottom of emotions, the human relations, the unspoken and unconscious rules of behavior in an implicit way” (cf. Ulijn & St.Amant, 2000, p. 221). The main contribution of this model is that it raises awareness to the complexity and implicitness of culture, as the largest part of an iceberg is below the surface. Cultural differences may become manifest in explicit document characteristics or explicit user behaviors, but can (and should) be traced back to differences in the unspoken and unconscious rules between cultures. This corresponds to Hofstede’s Onion Model of culture, which states that values are at the core of a culture and there are various layers around this core (rituals, heroes, and symbols) (cf. Hofstede et al., 2010). These models help to conceptualize the general phenomenon of culture, but do not have any explanatory value regarding differences in technical communication between two cultures.

Other researchers have proposed frameworks of cultural dimensions, to characterize differences between cultures. Hofstede and colleagues developed in total six cultural dimensions, which reflect the underlying values in national cultures (Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede et al., 2010). The dimensions were originally derived from a worldwide survey of cultural differences, among 100,000 IBM employees in 50 countries. The six dimensions are:

- High versus low power distance: The extent to which people accept and expect hierarchy and unequal distributions of power.

- Individualism versus collectivism: The extent to which people prefer a loose network in which they basically should take care of themselves, or a tight network in which people take care of each other and are loyal to each other.

- Masculinity versus femininity: The extent to which people value competition, achievement, assertiveness, and material awards, or cooperation, well-being, care for the weak, and quality of life.

- High versus low uncertainty avoidance: The extent to which people feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguous situations.

- Long-term versus short-term orientation: The extent to which people value thrift and education and prepare for the future, or hold on to old traditions and view change with suspicion.

- Indulgence versus restraint: The extent to which people value enjoying life and having fun, or value the regulation of such pleasures with strict social norms.

Hofstede’s dimensions are very influential in the research into intercultural and cross-cultural communication. They help to characterize differences between cultures beyond the eye-catching and superficial differences. Although there have been several attempts to translate the cultural dimensions into specifications for interface design or user support (for example, Marcus & Gould, 2000; see Reinecke & Bernstein, 2011 for an overview), the translations of the value-based dimensions into specific design guidelines are not validated and are often somewhat far-fetched. The step from Hofstede’s dimensions to the practice of intercultural or cross-cultural technical communication appears to be a big one.

Another influential dimension is Hall’s (1976) distinction between high-context and low-context cultures. Hall’s dimension is based on the communication characteristics among people, and are, as a result, conceptually closer to the practice of technical communication than Hofstede’s six dimensions. According to Hall, “high-context cultures find the majority of the information in the physical context or internalized in the person, while very little is in the coded, explicit, transmitted part of the message, whereas low context cultures are the opposite” (p. 91). In general, Western countries are on the lower end of the scale, and China is on the higher end of the scale. The implication for technical communication could be that Western users need more explicit and detailed instructions, and Chinese users may be used to work with more implicit and general instructions. However, these assumptions have not been tested so far.

It is important to note that these theories imply several simplifications regarding the phenomenon of culture in communicative processes (and the same applies to the research we describe in this article). They are clear examples of etic approaches, aiming more at objectively pinpointing differences than at understanding a culture from within. Furthermore, they approach culture as a static and homogeneous concept, whereas it is plausible that culture in real life is dynamic: It evolves over time, it can be situation or context dependent, and it may involve the interaction between different systems or layers of culture. Much emphasis is given to differences between national cultures, but it is likely that there are cultural variations within geographical boundaries—for instance based on regional differences, organizational or occupational differences, sub groups, and individual variations. An example of a more dynamic and heterogeneous approach within technical communication can be found in Sun (2006). In addition, Fang (2005-2006, 2012) challenges the validity of bipolar dimensions, and proposes a Chinese worldview that comprises “both-and” relationships between the poles of a dimension instead of the underlying “either-or” approach. From this perspective, cultural dimensions themselves already represent a culturally-biased Western view on culture. The simplifications help us understand differences between national cultures, but at the same time may obscure similarities between national cultures as well as differences within a national culture.

Furthermore, the theories mentioned above represent top-down approaches for studying cultural differences. The cultural dimensions may be translated into very specific characteristics of the communication. As such, the theories can be helpful for making sense of the notion of culture, and for making broad generalizations about differences between cultures. However, they seem to offer relatively little clear-cut guidance for designing interfaces and user instructions. Their influence in the technical communication literature is therefore limited. In the following section, we will present an overview of the insights about cultural differences based on technical communication research. The research can be characterized as a bottom-up approach, it starts with pinpointing very specific differences and, where possible, tries to generalize the findings.

Technical Communication and Cultural Differences

Several studies have been conducted into the cultural differences between Western countries and China within the field of technical communication. In total, we found and analyzed nine such articles (Barnum & Li, 2006; Ding, D. D., 2003; Dragga, 1999; Honold, 1999; Wang, J., 2007; Wang, Q., 2000; Wang, Y., & Wang, D., 2009; Yu, 2009; Zhu & St.Amant, 2007). We will first provide a broad overview of the studies. After that, we will focus on the differences found with respect to the structuring of user instructions, as this is the topic of our research.

Broad Overview of the Available Research

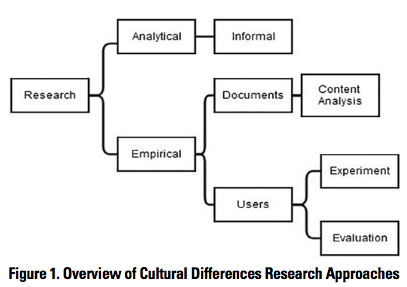

Figure 1 gives an overview of possible research approaches. We first distinguish between analytical approaches (without formal data collection), and empirical approaches (with formal data collection). A second distinction, within the empirical approaches, is that between a focus on documents and a focus on users. In the case of a focus on documents the research method is a (qualitative or quantitative) content analysis. In the case of a focus on users, a distinction can be made between experimental (or quasi-experimental) research and evaluation research. In experimental research, randomized groups of participants are exposed to manipulated document versions and the results are compared; in quasi-experimental research, the division of participants over conditions cannot be random (for instance when Chinese and Western participants are compared). In evaluation research, the reactions of one group of participants to one document version are examined.

Of the nine studies, we categorized one as an analytical approach (Dragga, 1999). The majority of the research could be categorized as content analysis (Barnum & Li, 2006; Ding, D. D., 2003; Wang, J., 2007; Wang, Q., 2000; Wang, Y., & Wang, D., 2009; Yu, 2009). Only two studies were (quasi-) experimental (Honold, 1999; Wang, Y., & Wang, D., 2009) and one study could be characterized as evaluation research (Zhu & St.Amant, 2007). However, it must be noted that the content analyses were generally rather informally conducted and reported, and that the two (quasi-)experimental studies did not meet the rigor that is normally associated with experiments. Although inspiring, the available research into cultural differences is methodologically not very strong, and the user’s perspective is both qualitatively and quantitatively underexposed.

Together, the nine studies identified potential differences between Chinese and Western technical communication in four main categories: structure, style, visual design, and user behavior. Structure is about the organization and clustering of documents, including the ordering of information, the use of headings, introductions, paragraphs, and links. As structure is the theme of our research, we will discuss the findings within this category in more detail in the next sub section.

Style involves the language use in documents. In general, simplicity and clarity seem to be valued higher in Western cultures than in China, given a preference for authoritative and official jargon, poetic language, and indirect and general expressions in Chinese documents (Barnum & Li, 2006; Zhu & St.Amant, 2007). Visual design involves the document layout as well as the use of tables and figures. In general, Western documents seem to use more page design elements (Barnum & Li, 2006; Wang, Q., 2000) and fewer illustrations (Wang, Y., & Wang, D., 2009) than Chinese documents. Besides, the relationship between visuals and text appears to be different: redundant and explicitly connected in Western documents, and complementary and not connected in Chinese documents (Barnum & Li, 2006; Ding, D. D., 2003; Wang, Q., 2000; Wang, Y., & Wang, D., 2009). User behavior refers to differences in the way users handle instructions. The literature suggests that Chinese users may have a better understanding of images than Western users, a stronger urge to immediately apply instructions, a stronger tendency to learn by heart, and an inclination to use online sources and interpersonal communication (Honold, 1999; Wang, Y., & Wang, D., 2009).

Of course, it cannot be emphasized enough that these conclusions should be treated with caution. We merely summarize findings that are reported in more detail and with more grayscale in the specific studies. Furthermore, it should be noted that many of these findings are based on single studies, conducted in very specific contexts.

Chinese and Western Views on Document Structure

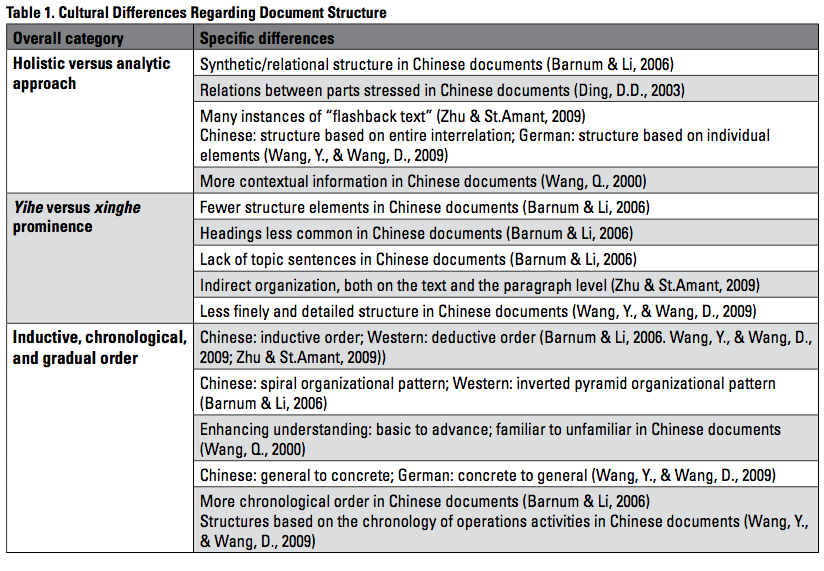

Below, we will discuss the research findings on document structure in more detail. Fortunately, the research findings on structural differences are more elaborate than those on differences in style, visual design, and user behavior. Table 1 provides an overview of the cultural differences regarding document structure that we found. We construed three overall categories to group the findings: (1) holistic versus analytic approach, (2) yihe versus xinghe prominence, and (3) inductive, chronological, and gradual order. All findings regarding structure are based on content analysis; user research is not available as yet.

Holistic versus Analytic Approach. According to Nisbett et al. (2001), the cognitive processes of East Asian people tend to be more holistic, whereas Western people have a tendency towards an analytic thinking pattern. Holistic thinking focuses predominantly on understanding an object in its entirety; analytic thinking assumes dissecting an object in its parts and figuring out how these parts contribute. This distinction is quite fundamental, and can be seen in many different fields, such as science, medicine, and art.

It seems plausible that such differences in thinking affect the way people write and use documents. Indeed, several studies found evidence for that. Barnum and Li (2006) observe that Chinese documents generally reflect a holistic approach, referring to it as “synthetic” (as opposed to “Cartesian”) thinking patterns. They connect this characteristic to eschewing headings (which would disrupt the flow) and an inductive organization (we will discuss these two characteristics under the other two sub headings). D. D. Ding (2003) further specifies the holistic thinking patterns by referring to a stronger emphasis on interrelations between instructions and other parts of a document. Likewise, Zhu and St.Amant (2009) notice relatively many instances of “flashback text” in a document: referrals to earlier parts, which Westerners would not find very useful and even potentially confusing. Comparing German and Chinese manuals, Y. Wang and D. Wang (2009) conclude that “a system was structured on the basis of an entire interrelation or context in the Chinese documents, but individually and separately structured as individual elements in the German ones” (p. 45). Furthermore, Q. Wang (2000) argues that new ideas are presented with more contextual information because of the holistic and relational thinking patterns.

Yihe versus Xinghe Prominence. An important difference between Chinese and Western languages can be summarized using the pinyin terms yihe and xinghe (somewhat related but not entirely identical to the linguistic terms parataxis and hypotaxis, respectively; cf. Li, 2011). Liu (2006) defines yihe as “the way to connect words and sentences by meanings and logics, but not linguistic forms (including lexical and morphological means),” and xinghe as “the way to connect words and sentences by linguistic forms” (p. 74). In a yihe-prominent language, clauses can be placed after each other without using means to make their relationship explicit; in a xinghe-prominent language, the relationship between clauses is specified. Lian (1993) speaks of “semantic coherence” versus “formal cohesion” (p. 46). The distinction appears to connect to the aforementioned notions of high-context and low-context cultures (Hall, 1977; cf. Wang, Y., & Wang, D., 2009). See the following examples:

Yihe-prominent language: It snowed hard. The plane was canceled. I had to postpone my holiday.

Xinghe-prominent language: It snowed hard, so the plane was canceled. Therefore I had to postpone my holiday.

Among translation scholars Chinese is considered to be a yihe-prominent language, while English and other Western languages are seen as xinghe-prominent languages (Li, 2011; Liu, 2006; Wang, J., 2007; Wang, T., 2010). Although yihe and xinghe prominence originally and predominantly apply to the sentence level, it is possible to apply them to the structuring of text as well (cf. Halliday, Matthiessen, & Matthiessen, 2014).

Several studies found evidence that yihe is the principle of organization in Chinese documents. Barnum and Li (2006), Y. Wang and D. Wang (2009), and Zhu and St.Amant (2009) all noticed that document structure is less explicitly defined in Chinese technical communication. Barnum and Li (2006), for instance, state that Chinese documents contain fewer structural elements such as headings and show a lack of topic sentences. They also show that elements such as an introduction and a conclusion have a less obvious structuring function than in Western documents. According to Y. Wang and D. Wang (2009), “[t]he German textbooks and service manuals were more finely and detailed structured than the Chinese ones” (p. 47). Zhu and St.Amant (2009) talk about an “indirect organization” and an “implied pattern,” largely without structural markers such as headings. They argue that even main points are often not clearly indicated as such, and that the lack of explicit structure can also be found on the paragraph-level, where “random bits of information seem to be combined in a paragraph, and it is left to the reader to intuit the overarching theme that holds this information together”(p. 178).

Inductive, Chronological, and Gradual Order. Fan (2000) states that the relationship to nature is one of the eight important Chinese cultural values and essential concepts. Tao, fatalism, and harmony all relate to this value. Therefore, Chinese people like to follow the natural process of how things happen. The preferred Chinese order of information in documents is inductive, chronological and gradual, which are assumed to reflect practical experience and cognition. In contrast, the Western order could be characterized as more businesslike and task-oriented.

Several studies found evidence for these assumptions. Barnum and Li (2006), Y. Wang and D. Wang (2009), and Zhu and St.Amant (2009) all observed that Chinese documents are often structured inductively, whereas Western documents often have a deductive organization. According to Barnum and Li (2006), this results “in a writing pattern that reflects a spiral, with the main idea developed in a roundabout or spiral pattern that emerges through the paragraph as well as the document” (p. 152).

Q. Wang (2000) found that Chinese popular science articles and instruction manuals are often structured from basic to advanced, and from familiar to unfamiliar, while Western manuals are more focused on specific tasks. Similarly, Y. Wang and D. Wang (2009) found that Chinese textbooks about an engine fuel injection system start from general information, whereas German textbooks start from the specific system. They noticed a corresponding difference in user behavior. Chinese users searched information from general to concrete, whereas German users searched from concrete to general.

Finally, both Y. Wang and D. Wang (2009) and Barnum and Li (2006) noticed a stronger emphasis on chronology as organizational principle in Chinese documents.

To Conclude

Our overview of earlier research shows that the insights about Sino-Western cultural differences are still limited and fragmented. In particular, user-based research is largely missing, and the content analytic research comparing document characteristics is somewhat informal and diverse. However, with regard to the structuring of documents some clear differences can be mentioned, which are all supported by more than one study. We summarized the differences using three (related) overall categories: (1) holistic versus analytic approach, (2) yihe versus xinghe dominance, and (3) inductive, chronological, and gradual order. These structural differences between Chinese and Western documents formed the starting point for our research.

Method

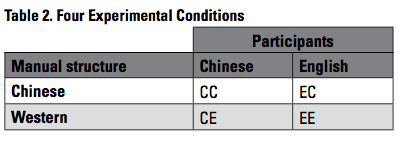

To answer the research question, a 2×2 experiment was designed, in which participants had to use user instructions to perform a number of tasks with a translation software package. Document structure (Chinese versus Western) and participants’ cultural background (Chinese versus Western) were the independent variables in our study, and task performance, knowledge, and appreciation of the software and the user instructions were the dependent variables. Table 2 gives an overview of the four conditions in the experiment.

Artifact: SDL Trados Studio 2014

We selected SDL Trados Studio 2014 as the software package for the experiment. SDL Trados is a popular computer-aided translation tool, used by over 200,000 translation professionals worldwide. The software is well-designed and available as a free 30-day trial version. It has both an English and a Chinese interface. And most importantly, it is a tool that is unfamiliar to people outside the field of professional translation, which made it possible to eliminate the influence of differences in prior knowledge and experience.

SDL Trados increases productivity and translation quality using translation memory and terminology management. Translation memory can be seen as the core technology of SDL Trados. It involves a database that stores previously translated text segments for future use, so that translators do not need to translate the same sentences twice. Terminology management involves a customized dictionary in which translators can create new entries and their definitions. This is particularly useful to safeguard consistency and accuracy of terms, especially in collaborative translation projects. The mechanisms of translation memory and terminology management are similar; the main difference is that translation management stores sentences or even paragraphs, whereas terminology management stores words or phrases.

In addition, SDL Trados helps to manage translation projects. Word counts, analyses and reports are automatically generated to monitor a translation project. SDL Trados also allows assigning specific tasks, setting deadlines, and tracking the status of a project.

User Tasks

We designed seven related user tasks that had to be performed with the SDL Trados Studio 2014 package. Participants had to create a translation memory within 25 minutes. They were not allowed to use any resources except for the user instructions they were given. The seven tasks all had to do with the (for outsiders difficult) concept of translation memory. For instance, two tasks were creating a new abbreviation, and creating an untranslatable element for the translation memory.

The principle of translation memory is as follows. Translation memory uses text alignment functions to split the original and translated texts into language pairs, and stores those pairs. When translators are working on a document, translation memory searches and compares what is being translated with previously translated segments, and provides suggestions. Translators may accept or reject the suggestions given by the translation memory. Even if there are no matches in a text, translators can save their work in the translation memory for future translation projects. As such, translation memory helps translators to avoid meaningless repetitive work and to focus on new texts. This is especially useful for large translation projects, in which the repetition rate is usually high. The translation memory is created by the translators, so it is empty at first. For an optimal use of its functionality, translation needs to be added in the translation memory. The larger the translation memory, the higher the reuse rate will be.

For our study, tasks centered on the translation memory were appropriate, as they involved both specific procedural instructions and a deeper understanding of the meaning of the concept translation memory.

Manipulations of the User Instructions

There are official manuals of Trados Studio 2014 available in various languages. The manual was designed in English by Western technical communicators, and then localized into other languages. The user instructions used in the experiment were designed based on the official manuals. They comprised three pages of information.

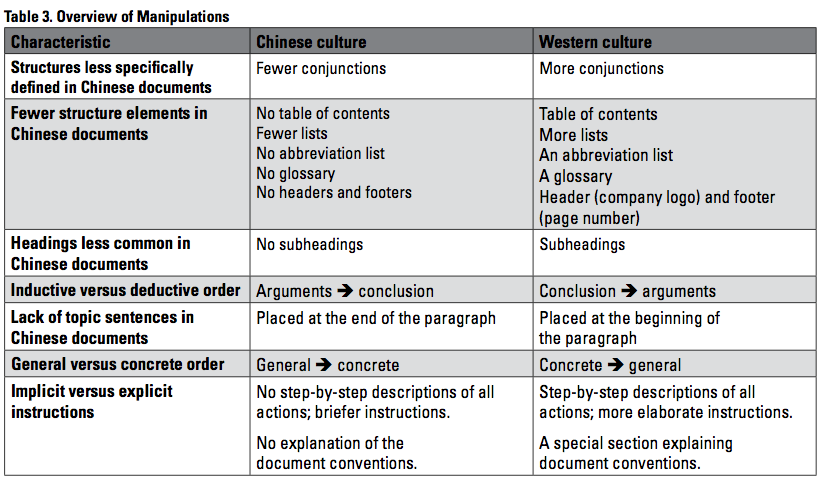

In total, we created four versions of the user instructions. For the specific user tasks selected, the relevant parts were redesigned in accordance with what prior research had found about Chinese and Western principles for structuring. Of both cultural versions, two language versions were made: a Chinese one and an English one. We did so to eliminate the influence of different language levels (for Chinese participants, an English manual is considerably further removed from their mother tongue than for Western participants), and also for reasons of ecological validity for the Chinese participants.

Table 3 provides an overview of the main structural differences between the two cultural versions. In the Appendix, specific examples (in English) of the materials are offered. During the design process of the user instructions, a certificated trainer of SDL Trados reviewed the manuals to make sure there were no mistakes related to the content about Trados. A professional translator reviewed and edited the re-designed (EE and CC) and translated versions (CE and EC) to make sure that they were completely equivalent.

Participants

Forty students with a Western cultural background and 40 Chinese students at the University of Twente were recruited for the research. Western was geographically defined in our study, and comprised Europe and North America. Of the Western participants, the majority had a Dutch (18) or German (12) background; other nationalities included: France, Albania, Spain, U.S., Italy, and Slovakia. None of the Western participants had ever been in China. All Chinese participants were from mainland China (the People’s Republic of China), and had come to the Netherlands to study. None of the participants had ever heard of the SDL Trados Studio 2014 software before. The male-female ratio was in perfect balance. We recruited participants with an engineering and a social sciences background. The ratio between those study backgrounds was also in perfect balance.

Using gender and study background as primary allocation criteria, we randomly assigned the Western participants to the conditions of the Chinese and Western cultural instructions in English, and assigned the Chinese students to both cultural versions in Chinese. This resulted in four perfectly similar groups of participants. Afterwards, we checked for differences in participants’ age. An analysis of variance showed that there were no significant differences between the conditions (the mean age was 22.7).

Procedure

The data were collected in individual sessions, which were all held in a quiet room. All participants used the same laptop computer. At the start of the session, the facilitator briefly introduced the experiment. Then the participants were asked to switch off their communication devices and read and sign a consent form. The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university.

Each participant received a document with the task description. They had up to five minutes to read it. When they indicated that they knew what they should do, one of the user instructions versions was handed to them and the facilitator started recording time. During the process, the facilitator observed and did not communicate with the participant. The participant was not asked to think aloud, to avoid reactivity in the data collection (Van den Haak, De Jong, & Schellens, 2003, 2007). The facilitator stopped recording time when the participant finished the task or when the time exceeded 25 minutes. As soon as the participant finished the task, he or she was asked to fill out a questionnaire. If the participant wanted to be informed about the results of the experiment, he or she could leave an email address.

After each experiment, the translation memory the participant had created was stored in different folders. Besides, all the records in Trados were deleted to make sure that the user interface was in its original status for the next participant.

Dependent Variables

Four dependent variables were included in the research: task performance, knowledge about the SDL Trados Studio 2014 package, appreciation of SDL Trados Studio 2014, and appreciation of the user instructions.

Task performance was measured using direct observation. The aggregated success score for the seven tasks was taken as an overall measure of effectiveness. These tasks formed a sufficiently reliable scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .75). The time taken for the complete set of assignments was used as a measure of efficiency. A last performance measure was the number of attempts by the users to create a translation memory (this is indicated by the number of translation memories a participant had created).

The remaining dependent variables were measured using a questionnaire, which the participants filled out after the task execution. Just like the rest of the research materials, the questionnaire was designed in English and Chinese. A professional translator reviewed and edited the questions, to make sure that they were equivalent.

Participants’ knowledge about SDL Trados Studio 2014 was measured using a set of nine comprehension questions, in the form of statements. Participants had to indicate whether they thought a statement was true or false, and also had a “don’t know” option. Examples of statements were “Translation memory enables translators to never translate the same sentences again,” and “Besides system elements, users can define customized fields in Trados.” Two measures were derived from the nine comprehension questions: a success score (total number of correct items), and a doubt score (total number of items with “don’t know” answer). The knowledge questions did not form a sufficiently reliable scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .53), which indicates that there is probably not one underlying construct. Still it can be maintained that more correct answers indicated more successful participants.

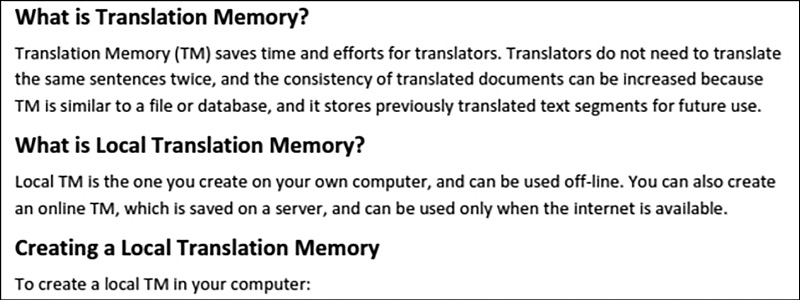

Participants’ appreciation of the SDL Trados Studio 2014 software involved both usability and usefulness. Usability was measured using items based on the Software Usability Scale (SUS). SUS is a reliable and robust scale for measuring the usability of a wide range of products and services (Bangor, Kortum, & Miller, 2008; Bangor, Staff, Kortum, & Miller, 2009; Lewis & Sauro, 2009). Examples of items are “I found Trados unnecessarily complex,” and “I felt very confident using Trados.” We complemented the usability questions with four items that focused more on satisfaction and experience (for example, “It is pleasant to use Trados”). Usefulness was measured using six items. Examples of items are “I think Trados is a useful tool for translators,” and “I think Trados meets the needs of translators.” All items were measured on five-point Likert scales. Factor analysis with Varimax rotation showed that there were three underlying constructs in this part of the questionnaire: usability-complexity (three items, Cronbach’s alpha = .62), usability-ease of use (nine items, Cronbach’s alpha = .90), and usefulness (six items, Cronbach’s alpha = .87).

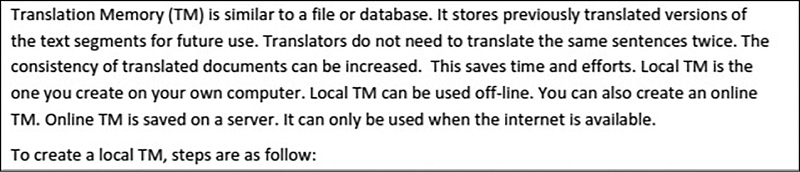

Participants’ appreciation of the user instructions involved four aspects: usability (eight items; for example, “I am satisfied with this manual,” and “the manual is user friendly”), language use (four items; for example, “The language of the manual is clear,” and “Sentences in the manual are complicated”), organization (nine questions; for example, “The structure of the manual is confusing,” and “I could easily find the information I need in the manual”), and layout (five items; for example, “The manual looks crowded and busy,” and “The manual is professionally designed”). Factor analysis with Varimax rotation showed initially that there were six underlying constructs, but after removal of confounding questions we ended up with a three-factor solution: instructions usability (five items, Cronbach’s alpha = .90), instructions structure (five items, Cronbach’s alpha = .86), and instructions language use (three items, Cronbach’s alpha = .73).

Results

We report the results of the experiment in four sub sections: task performance, comprehension, appreciation of SDL Trados Studio 2014, and appreciation of the user instructions. The data were analyzed using analysis of variance, with participant background and user instructions version as independent variables. We looked for main effects, which would indicate that either cultural background of the participants had a significant effect on the scores irrespective of the version of the user instructions they used, or the version of the user instructions had a significant effect on all participants. Most importantly, however, we looked for interaction effects, which would indicate that Chinese and Western participants reacted differently to the two versions of user instructions. A significant interaction effect would support our expectations. At the end of the Results section, we describe observations during the sessions with participants.

Task Performance

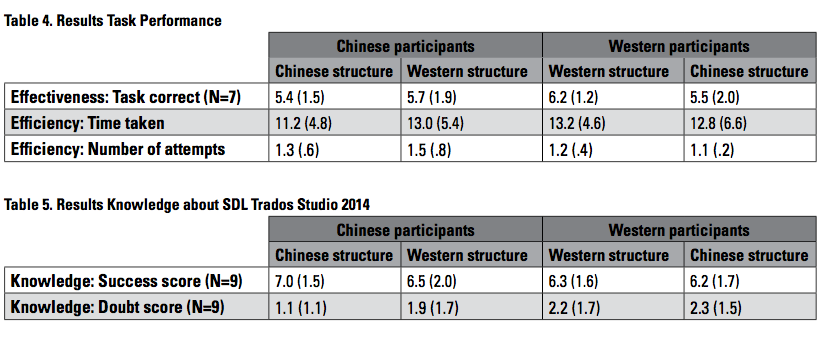

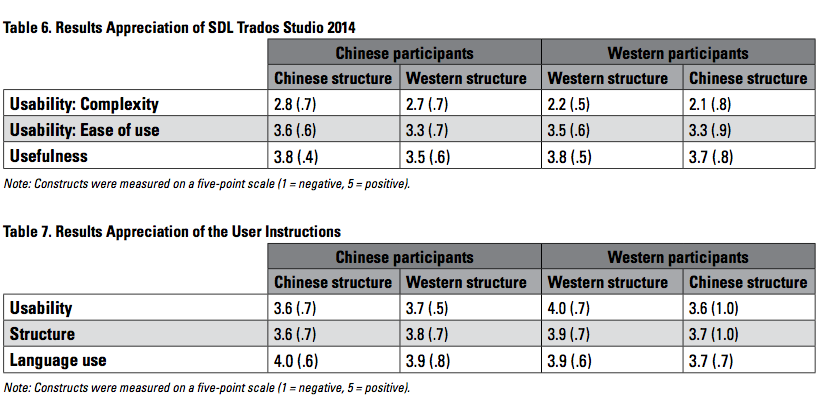

Table 4 shows the results of the four conditions on task performance. For effectiveness (number of tasks correct), no main effects were found of participant background (F(1,76)=.644, p=.425) and user instructions version (F(1,76) =1.79, p=.185), and, most importantly, no interaction effects were found (F(1,76) =.161. p=.689). Similar results were found for time taken. There was no significant main effect of participants’ background (F(1,76)=.481, p=.490), no significant main effect of user instructions version (F(1,76)=.811, p=.371), and no interaction effect (F(1,76)=.324, p=.571). Regarding the number of attempts, we found a significant main effect of participant background: The Chinese participants made more attempts to finish the task (F(1,76)=5.677, p<.05). We did not find a main effect of user instructions version (F(1,76)=2.30, p=.134) or an interaction effect (F(1,76)=.422, p=.518). From these results, it must be concluded that the version of the user instructions did not have a main effect on task performance, and that Chinese and Western participants did not work better with their own culturally adapted version.

Knowledge about SDL Trados Studio 2014

The results regarding the knowledge questions can be found in Table 5. The tendency is the same as with task performance. Regarding participants’ success score, no main effects were found for participant background (F(1,76)=1.71, p=.195) and for user instructions version (F(1,76)=.274, p=.602). Also no interaction effect was found (F(1,76)=.616, p=.435). Regarding participants’ doubt score, there was a significant effect of participant background: Western participants gave more “don’t know” answers (F(1,76)=4.627, p<.05). We found no main effect for user instructions version (F(1,76)=1.235, p=.270) and no interaction effect (F(1,76)=1.982, p=.163). These results corroborate the lack of significant effects regarding task performance.

Appreciation of SDL Trados Studio 2014 Software

The scores regarding the participants’ appreciation of the software package may be found in Table 6. Again, no significant effects involving user instructions version were found. For usability-complexity (how difficult the participants found the software), there was a significant effect of participant background: Western participants found it more difficult to use and learn Trados (F(1,76)=15.735, p<.001). However, we found no effect of the version of the user instructions (F(1,76)=.028, p=.867) and no interaction effect (F(1,76)=.253, p=.617). For usability-ease of use (how easy the participants found the software to work with), no significant main effects were found for participant background (F(1,76)=.091, p=.763) and user instructions version (F(1,76)=.031, p=.862), and no interaction effect was found (F(1,76)=2.412, p=.125). The results regarding usefulness followed the same pattern: no effect of participant background (F(1,76)=.381, p=.530), no effect of user instructions version (F(1,76)=.309, p=.580), and no interaction effect (F(1,76), 2.576, p=.113). Again, no evidence was found for main or differential effects of the version of user instructions.

Participants’ Appreciation of the User Instructions

To conclude, Table 7 presents the results regarding participants’ appreciation of the user instructions. Regarding the usability of the manual, no significant main effects were found for participant background (F(1,76)=.771, p=.383) and user instructions version (F(1,76)=2.575, p=.113). Also no interaction effects were found (F(1,76)=1.541, p=.281). Regarding structure, no significant main effects were found for participant background (F(1,76)=.221, p=.640) and user instructions version (F(1,76)=.997, p=.321), and no interaction effects (F(1,76)=.032, p=.861). Finally, for language use similar findings can be reported: no main effect of participant background (F(1.76)=1.781, p=.186;), no main effect of user instructions version (F(1,76)=.049, p=.825), and no interaction effect (F(1,76)=1.002, p=.320). It must therefore be concluded that the cultural adaptation of the manual did not even affect participants’ appreciation of the manual itself.

Observations

During the sessions, the facilitator made several observations about the participants’ behaviors. First, it was clear that the participants, both Western and Chinese, had a preference for exploring the software package themselves, using their prior general knowledge about software and their expectations of the translation tool. They only used the user instructions when they thought the task went beyond their previous knowledge, or when they had tried many times but failed. When in trouble, many participants first tried to use the embedded help in the software.

When using the user instructions, the participants, both Western and Chinese, appeared to be impatient: They tended to skip descriptions and “long” text parts, and seemed reluctant to turn pages (even though the user instructions only consisted of three pages). Some of the participants said that user instructions can only be helpful if they help solving problems. So they argued that the order of information (from most important to least important) should be trouble-shooting information, procedural information, and conceptual information.

A final observation involved a remarkable difference between the Chinese and the Western participants. Many Chinese participants appeared to see the experiment as a test, and wanted to how they performed compared to other participants. For instance, they asked how many participants had finished the tasks correctly, what their ranking was, or what the shortest completion time was. None of the Western participants asked such questions. This seems to reflect a stronger competitive orientation in Chinese culture.

Discussion

Main Findings

The research described in this article is a first attempt to systematically and experimentally investigate the effects of an isolated aspect of cultural adaptation (namely the structure of user instructions) on Western and Chinese users. The main findings of our study can be summarized very briefly and straightforwardly. Our experiment did not yield any evidence for the superiority of the Western or the Chinese way of structuring user instructions, nor did it confirm that culturally adapted user instructions work better for either Western or Chinese users. As such, the results do not seem to support the assumed relevance to adapt the structure of user instructions to the cultural background of users (Barnum & Li, 2006; Ding, D. D., 2003; Dragga, 1999; Honold, 1999; Wang, J., 2007; Wang, Q., 2000; Wang, Y., & Wang, D., 2009; Yu, 2009; Zhu & St.Amant, 2007).

If our results are confirmed in future research on user instructions, this may be indicative that cultural differences based on national culture—as far as they involve the structuring of user instructions—are counteracted by the emergence of a worldwide “community of practice” when it comes to using instructions (Eckert, 2006). A community of practice “identifies a social grouping not in virtue of shared abstract characteristics (for example, class, gender) or simple co-presence (for example, neighborhood, workplace), but in virtue of shared practice” (p. 683). It is imaginable that the situation of using user instructions in fact is highly similar for users from all cultures, and software and user instructions may create similar expectations, preferences and thought processes across cultures. This would relativize the relevance of cultural differences in a very small area, namely concerning the structuring of user instructions.

However, it should be kept in mind that this is only a first, single experiment into this phenomenon, and our research experiences give way to several methodological considerations that may have implications for future research. So it is not the time to draw firm conclusions about the irrelevance of cultural adaptations of the structure of user instructions. Instead, we see it as an opening to further discussion of this theme.

The results of our study may be considered far from spectacular. In general, researchers often feel reluctance to publish research that only yields nonsignificant results. There is value in our study, however, in avoiding significance bias in the academic literature (this refers to a tendency among researchers to mostly submit studies with significant results, and a tendency in editorial processes to mostly accept studies with significant results, which may lead to a biased overall picture), in setting the stage for more user-based intercultural or cross-cultural research in technical communication, and in sharing and discussing methodological issues with this type of research.

Methodological Considerations and Suggestions for Future Research

Several methodological considerations follow from our results and experiences. A first consideration involves the position of the user instructions in our study. From our observations, we noticed reluctance among the participants to actually use the user instructions during their task performance. Within the sessions, the user instructions may have played a less prominent role in the perspective of the users than we originally foresaw. This may have weakened the sensitivity of the research design to find effects of the cultural adaptations. Solutions may be found in different directions. On the one hand, we could think of designing an experiment in which participants are obliged to use the manual (even though that may be hard to implement). On the other hand, we could think of using a different technical communication genre than user instructions (some of the content analytic studies focused more on technical reports and Web sites, for instance). It would be interesting to replicate our study in either direction.

Another consideration involving the user instructions might be that both versions of the user instructions were still relatively far removed from what would be an ideal type of user support in the eyes of the participants. In our research we based our materials on an existing manual, which could be considered to be positive for the ecological validity of the research. However, in the view of (at least some of) the participants, our variations in structuring may merely reflect marginal differences, when compared to the structure they would find more geared toward adequate user support: for instance, instructions supporting the exploratory behaviors of users, and offering help when they get stuck, comparable to the principle of “Minimalism” (cf. Van der Meij & Carroll, 1995). Indeed, our observations suggest that exploratory user behavior and reluctance to use the instructions were prominent among users of both cultural backgrounds. A problem here is that there is no content analytic research in this very specific area that can help us guide the design of experimental materials.

One could also question other choices that we made in our research. For instance, it is conceivable that the advantages of structure will become more apparent to users when the amount of text they are exposed to is larger and when navigating is a more prominent aspect of the task execution. It is also imaginable that a larger task, more tasks with the software package, or a higher task complexity would challenge the design of the user instructions more, and therefore would generate more sensitivity to pinpoint cultural differences. The mean scores on task performance and comprehension were relatively high in our study. A replication with longer documents of user instructions and larger, more, or more complex tasks would be an interesting follow-up to this study.

A last consideration involves the selection of participants. The Chinese participants in our study all lived and followed education in The Netherlands, and therefore may have been influenced by the Western way of structuring documents. It would be interesting to replicate our study with participants in China who never went abroad. It should be noted, though, that such a cultural influence assumption may only be an explanation for the lack of significant findings among Chinese participants: They may originally be used to the Chinese way of structuring, but in their acculturation process in the Netherlands have also gotten used to the Western way of structuring. We cannot explain the lack of significant findings among Western participants, who had never been to China before, but apparently had no clear preference for the Western way of structuring.

In sum, more research is needed in this fascinating area of investigation. The design and results of our study and our experiences and observations provide various interesting areas for future research. And let us not forget the other domains that we identified: style, visual design, and user behavior. Given the growing importance of intercultural and cross-cultural technical communication, more research attention for cultural differences between users is in our view essential.

Practical Implications

Although it is too early for firm conclusions, our research shows that it may be ill-advised to simply adopt the suggestions given by content analytic studies about differences between Western and Chinese documents in the way information is structured. The practices of Western and Chinese technical communicators may indeed reflect cultural differences, but may not reflect the preferences of users. Neither of the two versions of the user instructions appeared to be superior for either of the two cultural backgrounds. As such, the results may relativize the importance of structuring in user instructions, or call for a more drastic, user-centered way of structuring that goes beyond either version of the instructions used. It should be noted that such a conclusion can only be preliminary at this stage, and that the research findings do not apply to cultural differences on other aspects (for example, style or visual design) and cultural differences in the structuring of other technical documents (for example, reports).

APPENDIX: Examples of the Manipulations

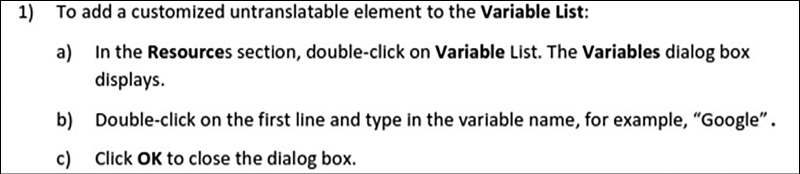

1. Use of Subheadings

Western version: Subheadings

Chinese version: No subheadings

2. Deductive Versus Inductive Order

Western version: Deductive (conclusion ➞ arguments)

Chinese version: Inductive (arguments ➞ conclusion)

3. Explicit Versus Implicit Instructions

Western version: Explicit instructions (with lists)

Chinese version: Implicit instructions (without lists)

4. Concrete-to-General Versus General-to-Concrete Order

Western version: Concrete-to-general order

Chinese version: General-to-concrete order

References

Agboka, G. Y. (2013). Participatory localization: A social justice approach to navigating unenfranchised/disenfranchised cultural sites. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22(1), 28-49.

Bangor, A., Kortum, P. T., & Miller, J. T. (2008). An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 24(6), 574–594.

Bangor, A., Staff, T., Kortum, P., & Miller, J. (2009). Determining what individual SUS scores mean : Adding an adjective rating scale. Journal of Usability Studies, 4(3), 114–123.

Barnum, C., & Li, H. (2006). Chinese and American technical communication: A cross-cultural comparison of differences. Technical Communication, 53(2), 143–166.

Barnum, C. M., Philip, K., Reynolds, A., Shauf, M. S., & Thompson, T. M. (2001). Globalizing technical communication: A field report from China. Technical Communication, 48(4), 397-420.

Chao, M. C., Singh, N., Hsu, C.-C., Chen, I.F. N., & Chao, J. (2012). Web site localization in the Chinese market. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 13(1), 33-49.

Coppola, N. W. (2010). The Technical Communication Body of Knowledge initiative: An academic-practitioner partnership. Technical Communication, 57(1), 11-25.

Ding, D. D. (2003). The emergence of technical communication in China—Yi Jing (I Ching) the budding of a tradition. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 17(3), 319–345.

Ding, D. D. (2011). When traditional Chinese culture meets a technical communication program in a Chinese university: Report on teaching technical communication in China. Technical Communication, 58(1), 34–51.

Ding, D. D., & Jablonski, J. (2001). Challenges and opportunities: Two weeks of teaching technical communication at Suzhou University, China. Technical Communication, 48(4), 421–434.

Ding, H. (2010). Technical communication instruction in China: Localized programs and alternative models. Technical Communication Quarterly, 19(3), 300–317.

Dragga, S. (1999). Ethical intercultural technical communication: Looking through the lens of Confucian ethics. Technical Communication Quarterly, 8(4), 365–381.

Duan, P., & Gu, W. (2005). English for specific purposes: The development of technical communication in China’s universities. Technical Communication, 52(4), 434-448.

Eckert, P. (2006). Communities of practice. In K. Brown (Ed.), Encyclopedia of language and linguistics (2nd ed.) (pp. 683-685). Boston, MA: Elsevier.

Fan, Y. (2000). A classification of Chinese culture. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 7(2), 3–10.

Fang, T. (2005-2006). From “onion” to “ocean”: Paradox and change in national cultures. International Studies of Management & Organization, 35(4), 71-90.

Fang, T. (2012). Yin yang: A new perspective on culture. Management and Organization Review, 8(1), 25-50.

French, W. L., & Bell, C. (1979). Organization development: Behavioral science interventions for organization improvement. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Gao, Z., Yu, J., & De Jong, M. (2013). Technical communication in China: A world to be won. Intercom, 60(1), 11-13.

Gao, Z., Yu, J., & De Jong, M. (2014). Technical communication education at the Peking University: Establishing technical communication as a professional discipline. tcworld (August), 11-13.

Hall, E. T. (1977). Beyond culture. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Hall, M., De Jong, M., & Steehouder, M. (2004). Cultural differences and usability evaluation: Individualistic and collectivistic participants compared. Technical Communication, 51, 489–503.

Halliday, M., Matthiessen, C. M. I. M., & Matthiessen, C. (2014). An introduction to functional grammar. (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Honold, P. (1999). Learning how to use a cellular phone: Comparison between German and Chinese users. Technical Communication, 46(2), 196–205.

Hu, Q. (2004). Technical writing, comprehensive discipline and scientific translation. Chinese Science & Technology Translators Journal, 17(1), 44–46.

Lentz, L., & Hulst, J. (2000). Babel in document design: The evaluation of multilingual texts. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 43(3), 313–322.

Lewis, J. R., & Sauro, J. (2009). The factor structure of the system usability scale. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 5619, 94-103.

Li, J. (2011). Xinghe vs. yihe in English-Chinese translation – Analysis from the perspective of syntactic construction. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 19(3), 189–203.

Lian, S. (1993). Contrastive studies of English and Chinese [in Chinese]. (2nd ed.). Beijing, China: Higher Education Press.

Liu, B. (2006). Comparison and translation of Chinese and English [in Chinese]. Beijing, China: China Translation and Publishing Corporation.

Marcus, A., & Gould, E. W. (2000). Cultural dimensions and global Web user-interface design. Interactions, 7(4), 32–46

Maylath, B. (2013). Current trends in translation. Communication & Language at Work, 1(2), 41-50.

Maylath, B., Vandepitte, S., Minacori, P., Isohella, S., Mousten, B., & Humbley, J. (2013). Managing complexity: A technical communication translation case study in multilateral international collaboration. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22(1), 67-84.

McCool, M., & St.Amant, K. (2009). Field dependence and classification: Implications for global information systems. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60, 1258-1266.

McLuhan, M. (1962). The Gutenberg galaxy: The making of typographic man. Toronto, CA: University of Toronto Press.

Miao, J., & Gao, Q. (2010). Building special programs for MTI — Concepts and contents of technical writing [in Chinese]. Chinese Translation, 2, 35–38.

Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108(2), 291–310.

Peng, K., Nisbett, R. E., & Wong, N. Y. C. (1997). Validity problems comparing values across cultures and possible solutions. Psychological Methods, 2(4), 329-344.

Reinecke, K., & Bernstein, A. (2011). Improving performance, perceived usability, and aesthetics with culturally adaptive user interfaces. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 18(2), 1–29.

St. Germaine-Madison, N. (2009). Localizing medical information for U.S. Spanish-speakers: The CDC campaign to increase public awareness about HPV. Technical Communication, 56(3), 235-247.

Sun, H. (2006). The triumph of users: Achieving cultural usability goals with user localization. Technical Communication Quarterly, 15(4), 457-481.

Tegtmeier, P., & Thompson, S. (1999). China is hungry: Technical communication in the People’s Republic of China. Technical Communication, 46(1), 36–41.

Ulijn, J., & St.Amant, K. (2000). Mutual intercultural perception: How does it affect technical communication? Some data from China, the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Italy. Technical Communication, 47(2), 220–237.

Van den Haak, M. J., De Jong, M. D. T., & Schellens, P. J. (2004). Retrospective vs. concurrent think-aloud protocols: Testing the usability of an online library catalogue. Behaviour & Information Technology, 22(5), 339-351

Van den Haak, M. J., De Jong, M. D. T., & Schellens, P. J. (2007). Evaluation of an informational Web site: Three variants of the think-aloud method compared. Technical Communication, 54(1), 58-71.

Van der Meij, H., & Carroll, J. M. (1995). Principles and heuristics for designing minimalist instruction. Technical Communication, 42(2), 243-261.

Van der Meij, H., Karreman, J., & Steehouder, M. (2009). Three decades of research and professional practice on printed software tutorials for novices. Technical Communication, 56(3), 265-292.

Wang, C., & Wang, D. (2011). Technical writing and cultivation of professional translators. Journal of PLA University of Foreign Languages, 34(2), 69–73.

Wang, J. (2007). Thoughts on xinghe and yihe. Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 39(6), 409–416.

Wang, J. (2009). Convergence in the rhetorical pattern of directness and indirectness in Chinese and U.S. business letters. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 24(1), 91–120.

Wang, Q. (2000). A cross-cultural comparison of the use of graphics in scientific and technical communication. Technical Communication, 47(4), 553–560.

Wang, T. (2010). Comparison of xinghe and yihe in English-Chinese translation. Journal of Chifeng University, 31(7), 143–144.

Wang, Y., & Wang, D. (2009). Cultural contexts in technical communication: A study of Chinese and German automobile literature. Technical Communication, 56(1), 39–50.

Yu, H. (2009). Putting China’s technical communication into historical context : A look at the Chinese culinary instruction genre. Technical Communication, 56(2), 99–110.

Yu, H. (2010). Integrating technical communication into China’s English major curriculum. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 25(1), 68–94.

Zhu, P., & St.Amant, K. (2007). Taking traditional Chinese medicine international and online: An examination of the cultural rhetorical factors affecting American perceptions of Chinese-created Web sites. Technical Communication, 54(2), 171-186.

Zhu, P., & St.Amant, K. (2010). An application of Robert Gagne’s nine events of instruction to the teaching of website localization. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 40(3), 337-362.

About the Authors

Qian Li received a double master’s degree of technical communication and computer-aided translation from the University of Twente (The Netherlands) and Peking University (China). She is now a PhD candidate at the University of Twente. Contact: q.li@utwente.nl

Menno D.T. de Jong is a full professor of communication science at the University of Twente (The Netherlands). He specializes in technical and organizational communication and is the former editor of Technical Communication. Contact: m.d.t.dejong@utwente.nl

Joyce Karreman is an assistant professor of communication science at the University of Twente (The Netherlands). Her research interests include the design, the use, and the evaluation of instructive documents. She teaches courses in technical writing and user support. Contact: j.karreman@utwente.nl

Manuscript received 21 July 2015; revised 13 August 2015; accepted 14 August 2015.