By Diane Martinez

INTRODUCTION

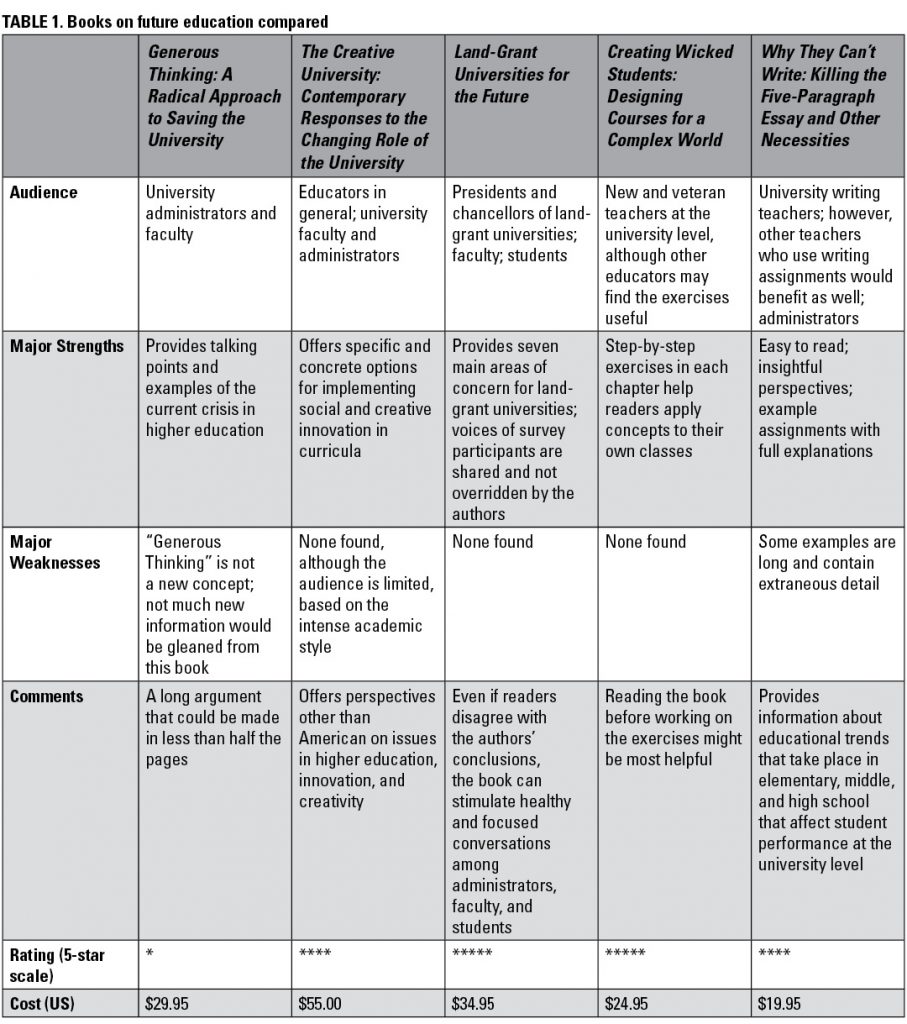

My goal in putting this series together was to read about the current conversations regarding higher education, starting with a broad stroke of the university and narrowing down to the classroom. I wanted to see what talking points these books had in common, if any, and what are some possible ways forward. One common theme I found is that the economic model of rankings and competition has degraded creativity and innovation in research, teaching, and service at universities. It also became clear that conversations about the current state and future of higher education around the world is a crucial conversation for all citizens, not just for academics, because creativity and innovation are the cornerstones of progress for any civilization.

GENEROUS THINKING: A RADICAL APPROACH TO SAVING THE UNIVERSITY

Generous Thinking: A Radical Approach to Saving the University is a timely book, given current debates regarding higher education in the United States. After World War II, the university was generally thought of as a public good that provided benefits to greater society; however, in recent decades, obtaining a college degree has been considered a private privilege, endeavor, and responsibility. Consequently, the public has become suspicious and possibly resentful about supporting an institution that is no longer seen as a public service but rather a place for only certain individuals to receive personal benefit. Kathleen Fitzpatrick connects this trend of the privatization of higher education with a lack of communication and engagement with the publics that universities are meant to serve. Her claim is that universities, and the people that work in and around them, need to shift their thinking regarding the work they do and who they ultimately serve from one of competitiveness and individuality to public service. Such change, Fitzpatrick claims, can occur through “generous thinking.”

Generous Thinking: A Radical Approach to Saving the University is a timely book, given current debates regarding higher education in the United States. After World War II, the university was generally thought of as a public good that provided benefits to greater society; however, in recent decades, obtaining a college degree has been considered a private privilege, endeavor, and responsibility. Consequently, the public has become suspicious and possibly resentful about supporting an institution that is no longer seen as a public service but rather a place for only certain individuals to receive personal benefit. Kathleen Fitzpatrick connects this trend of the privatization of higher education with a lack of communication and engagement with the publics that universities are meant to serve. Her claim is that universities, and the people that work in and around them, need to shift their thinking regarding the work they do and who they ultimately serve from one of competitiveness and individuality to public service. Such change, Fitzpatrick claims, can occur through “generous thinking.”

Generous thinking is “a mode of engagement that emphasizes listening over speaking, community over individualism, [and] collaboration over competition” (p. 4). Thus, Fitzpatrick sets out to explain the concept of generosity and how it applies to building a better relationship between the university and publics. In particular, she spends two chapters discussing how faculty can engage and inform the public about their research and work by reading together. Given that the public funds most state universities, she makes the case that the research and work that goes on at a university should not be hidden from the public through publication in only obscure venues, such as academic journals, which are not intended for public consumption. She explains that faculty, for instance, can make public appearances, but they should also make their work publicly accessible. Publicly accessible, to Fitzpatrick, means posting work in public spaces, using open source publication processes, writing for public audiences, and seeking public commentary, as she did with the original manuscript of her book. Her main argument is that the university sets itself up as being superior to those outside the borders of academia, but the public has plenty to contribute to the work taking place on campuses. Such participation and engagement would clearly demonstrate how the university is a public good, which would create community linkages between the university and the public, and, consequently, once more garner public support.

Higher education is in a crisis, most especially the arts and humanities. Federal mandates force universities into the role of being a means for only workplace preparation, and such demands have changed the university environment and what it means to have a college education. Thus, a book that addresses such critical issues in our society is important. The problem with Generous Thinking, however, is that Fitzpatrick offers too little. In the Introduction, she states “I am asking us to take a closer look at the ways that we connect with a range of broader publics” (p. 4). The key here is the word, “look,” which is basically all she does. What she offers is a scholarly piece of writing on the abstract concepts of community, connection, commitment, and engagement. In fact, the writing comes off as a composite of so many sources with long-winded explanations of their significance to her overall argument that trying to track down the main ideas for each chapter is a constant hunt. And she offers no real solutions. Fitzpatrick ends the book with the obvious question: “‘okay, so what do we do?’…a question that is going to require more minds than mine to answer” (p. 236). The book is basically ‘here’s what we all have to think about,’ but anyone who is mildly aware of mainstream media coverage on higher education would already be asking the same questions she does. The idea of generous thinking becomes just a term Fitzpatrick uses to say ‘we have to do better to connect with the public,’ which, yes, is true, but that same argument could have been made just as well in probably less than half the length of the book.

THE CREATIVE UNIVERSITY: CONTEMPORARY RESPONSES TO THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE UNIVERSITY

The Creative University: Contemporary Responses to the Changing Role of the University is a selection of papers from the 2016 Creative University Conference at Aalborg University, Denmark, which “represent a range of responses to the question: What is a ‘creative university’?” (p. 1). The creative university is difficult to pin down in that it is a concept, a “response to societal changes” (p. 1) that calls for new pedagogies to “develop students’ innovative and creative thinking, where students as well as teachers are expected to break with habitual actions and thoughts” (p. 2). This concept presents a tall order for higher education due to the multitude of philosophical questions it raises, many that are addressed in this book. Thus, it is a beneficial book for educators, graduate students, and employers across disciplines.

The Creative University: Contemporary Responses to the Changing Role of the University is a selection of papers from the 2016 Creative University Conference at Aalborg University, Denmark, which “represent a range of responses to the question: What is a ‘creative university’?” (p. 1). The creative university is difficult to pin down in that it is a concept, a “response to societal changes” (p. 1) that calls for new pedagogies to “develop students’ innovative and creative thinking, where students as well as teachers are expected to break with habitual actions and thoughts” (p. 2). This concept presents a tall order for higher education due to the multitude of philosophical questions it raises, many that are addressed in this book. Thus, it is a beneficial book for educators, graduate students, and employers across disciplines.

Like the concerns raised in Generous Thinking, contributors to The Creative University address pressing issues related to universities increasing their interaction with the public, moving away from standardized performance metrics and fostering creativity through innovative instruction, for instance. They present concrete examples of creative and innovative pedagogy, as well as discuss reasons why higher education must move away from standardization that relies on mere economics and metrics to motivate knowledge production and knowledge exchange. For instance, the chapter “The Importance of Imagination in Educational Creativity When Fostering Democracy and Participation in Social Change” describes how students responded and reimagined an energy solution when a nuclear power plant was proposed in a Danish community. In response to the overall social rejection of the power plant, students and faculty at a Danish Folk High School built the world’s largest windmill. The chapter, however, is not only a narrative about how this technological and social feat was accomplished; it discusses the philosophical concepts, such as how creativity is defined, what elements make up a democratic education, and where does student agency fit into these larger concepts.

I don’t normally provide a laundry list of topics covered in a book; however, it is worth highlighting the wide range of philosophical concepts and creative and innovative pedagogy readers will encounter in this book, including:

- using practice-based research to produce “something that requires long hours, intense thought, and considerable technical skill” (p. 31);

- teaching students to be comfortable with uncertainty and have productive failings;

- exploring whether Bildung has “any relevance in the postmodern world of instrumentalist and pragmatic approaches to education” (p. 53);

- using constructivism to foster innovation and creativity in instruction;

- defying economic narratives where knowledge is judged by its economic impact and moving instruction toward traditional academic values associated with social engagement with citizens;

- presenting a new model university focused on “social entrepreneurship and social inclusion than on market-oriented activities” (p. 150); and

- developing a digital public university that also serves as a public good.

What many contributors point to is that quantity does not equal quality and that, in many ways, “one root cause of the lack of theoretical advance is the academic incentive system; where it has become more important to be productive than creative” (p. 144). Thus, there is a strong commitment to reimaging the postmodern university that has taken an economic turn and consequently stifled innovative and creative learning, thinking, and actions, the very elements that allow civilization to progress.

LAND-GRANT UNIVERSITIES FOR THE FUTURE: HIGHER EDUCATION FOR THE PUBLIC GOOD

Land-Grant Universities for the Future: Higher Education for the Public Good is based on a survey conducted by Stephen M. Gavazzi and E. Gordon Gee with 27 land-grant university presidents and chancellors who agreed to participate in the study. The survey consisted of four basic questions on the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) to land-grant universities.

Land-Grant Universities for the Future: Higher Education for the Public Good is based on a survey conducted by Stephen M. Gavazzi and E. Gordon Gee with 27 land-grant university presidents and chancellors who agreed to participate in the study. The survey consisted of four basic questions on the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) to land-grant universities.

Before launching into their study results, the book begins with a chapter on the historical mission of land-grant universities and the evolution of these universities over the past 150 years. This is an important chapter because the “land-grant mission is not a well-known concept among American citizens” (p. 29), and “there is tremendous variation in how the land-grant mission is expressed across America” (p. 40). The First and Second Morrill Acts, the Hatch Act, and the Smith-Lever Act all played significant roles in defining the core activities of the land-grant university—teaching, research, and service—but there is no set mandate on what it means to engage with the community. In other words, how does the land-grant university serve the very people it was intended to serve?

Probably the most interesting chapter of the book, “Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats” outlines seven themes that emerged from the SWOT analysis study, which are provided below.

1) Concerns about funding declines versus the need to create efficiencies

2) Research prowess versus teaching and service excellence

3) Knowledge for knowledge’s sake versus a more applied focus

4) Focus on ranking versus an emphasis on access and affordability

5) Meeting the needs of rural communities versus the needs of a more urbanized America

6) Achieving global reach versus closer-to-home impact

7) Exploring benefits of higher education versus the devaluation of a college diploma (pp. 59–60)

Supported by lengthy quotes from survey responses, the authors explain each theme as it relates to the historical, present, and future of land-grant universities.

Understanding the issues alone is not enough to chart a future for land-grant universities, and wisely, the authors included chapters on the impact of governing bodies, and the role and impact of faculty and of students, each chapter addressing the seven themes from varying perspectives. Land-Grant Universities for the Future ends with “Charting the Future of American Public Education,” a chapter dedicated to answering the “‘so what?’ question” (p. 150) and aimed to provide guidance toward “restoring the American citizenry’s confidence in its public institutions of higher learning through the establishment and maintenance of more harmonious relationships with community stakeholders” (p. 150). Additionally, the authors advocate for an undergraduate course on understanding the mission of land-grant universities and building leadership and advocates in the 21st century for these institutions. A syllabus for the course is provided as an appendix.

The book’s audience reaches beyond presidents and chancellors; it is accessible and pertinent to undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, board members, and state legislators, all who will benefit from the candid discussions about critical issues that affect not only land-grant universities, but all American public higher education in the present century.

CREATING WICKED STUDENTS: DESIGNING COURSES FOR A COMPLEX WORLD

I consider myself an experienced professor, and I put a lot of work and time into designing and redesigning my courses every semester; however, Creating Wicked Students: Designing Courses for a Complex World opened my eyes to how I can improve my classes and better prepare my students to be creative, critical, and contributing members of a particular field and of society at large; in other words, how to be “wicked students.”

I consider myself an experienced professor, and I put a lot of work and time into designing and redesigning my courses every semester; however, Creating Wicked Students: Designing Courses for a Complex World opened my eyes to how I can improve my classes and better prepare my students to be creative, critical, and contributing members of a particular field and of society at large; in other words, how to be “wicked students.”

In this book review series so far, the progression of texts has moved from general concepts of rethinking higher education, creating new university models, and revisiting historical missions to adjust for modern times, to this current book on designing courses that prepare students for today’s expeditiously dynamic world. Through this series of texts, one thing is constant: What we’ve done in the past does not work today; we must educate students in ways that prepare them to deal with today’s “wicked problems, that is, situations where the parameters of the problem and the means available for solving them [are] changing constantly” (p. 3). Most educators want students to participate in life in “thoughtful and constructive ways” (p. 4), and Paul Hanstedt provides readers with valuable resources and guidelines for doing just that at the course level. He focuses on giving students authority through “authorship, the ability to write and rewrite, shape, and create” (p. 5). Our courses, he contends, must be training grounds for students to practice authority while they are learning, not delaying the practice for when they graduate. Thus, this book is intended to help instructors design courses that “develop students’ capacity to be engaged and deliberate citizens” who “engage in meaningful dialogue with the larger sociopolitical contexts beyond college” (p. 9).

Chapters are scaffolded to address course design issues as a progression: goals, course structure, assignments, exams, pedagogical techniques, and assessment. There are even two stopping points in the book, Intermission chapters, that encourage readers to pause, reflect on previous chapters, the exercises they’ve worked through, and prepare for the next section. Creating Wicked Students is craftily written to allow readers the option to read and work through the chapters and exercises in order or skip around as they see fit.

There are many helpful qualities about this book that bear mentioning, such as the multiple boxed exercises in each chapter with step-by-step instructions to work on new or existing courses all the way from goals to assessment. Resources like Krathwohl’s revision of Bloom’s taxonomy help to develop course goals that push students to assume authority, and numerous examples that show readers how to take a seemingly good goal, assignment, or exam question, and move it into contexts of uncertainty that allow students to synthesize information and “‘make decisions in the midst of uncertainty’” (p. 66). Hanstedt does a superb job of not locking assignments into certain disciplines; he explains and shows how one assignment in social sciences, for instance, can be modified to fit an English class. By the time readers reach the end of the book that includes six appendices with six different assignments, it is easy to see how those assignments can be revised for almost any course a reader may teach.

Like the Intermission chapters, the conclusion offers a final breath to reflect on Creating Wicked Students as a whole, and Hanstedt offers four cautions about course design that are worth considering. I wonder if that advice might be better put up front because the book can be overwhelming if read cold and worked through one chapter at a time. Readers might consider reading the book through one time and then going back and working on the exercises gradually. Both veteran and new teachers—and subsequently their students—will benefit greatly from either a quick or in-depth read of this book.

WHY THEY CAN’T WRITE: KILLING THE FIVE-PARAGRAPH ESSAY AND OTHER NECESSITIES

For the last book in this series, I wanted to look at higher education in the classroom. Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities delivers this perspective from both teachers and students.

For the last book in this series, I wanted to look at higher education in the classroom. Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities delivers this perspective from both teachers and students.

Part I: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay is on target with the book’s title and provides overarching reasons for why “Johnny Could Never Write.” John Warner argued that students are not successful writers after they graduate because they are not taught writing in ways they will experience it outside of the classroom. There is a system-wide emphasis on product, not process—and a whole host of other reasons that make up Part II: The Other Necessities.

It is in this second part where I became disoriented to the book’s purpose based on what I thought I was getting into; I thought I was reading about how to teach writing. Part II, however, is about almost everything we are doing wrong in our educational system. When I say “we,” though, I mean the mandates and faddish curricula that trickle down to teachers from those on the high court of education, some who are not even educators but businesspeople, many with a product to sell. At first I kept wondering when Warner was going to get back to writing, but chapter after chapter I was fascinated by the ludicrous twists and turns that national educational standards and policies have taken, many of which often countered research that had been around for years before the latest fad taking hold. I was also shocked to read what goes on in public schools today, such as the use of “ClassDojo, a behavior-tracking app that lets teachers award points or subtract them based on a student’s conduct” (p. 46). As Warner pointed out, just how would anyone feel about school when your performance is constantly being monitored and displayed for all to see? It’s no wonder that some students proclaim to love learning and hate school as he mentioned several times. Although I didn’t catch it immediately, Part II is important to understanding Part III because it describes what students face on a regular basis regarding school atmosphere, how they are under constant surveillance, the stress they face with standardized testing, and the faddish curricula they must weather every few years, including trends associated with technology.

Part III offers exactly what it is titled: “A New Framework.” This part of the book rides the waves of the previous section and offers countermeasures to those problematic mandates. By providing thorough explanations and example assignments, Warner shows how to “make writing meaningful and make meaningful writing.” Part IV: Unanswered Questions touches on lingering questions, such as how to teach grammar, what to do about grades, how this information applies to younger students, and what kind of support teachers really need.

Why They Can’t Write was an inspiring read that should not be limited to teachers; I highly recommend it for administrators, too. There were times in the early part of the book where some examples became extraneous, but the good news is that Warner is a talented writer where I never had to backtrack or read over anything twice to get his point.

REFERENCES

REFERENCES

Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. 2019. Generous Thinking: A Radical Approach to Saving the University. John Hopkins University Press. [ISBN 978-1-4214-2946-5. 260 pages, including index. US$29.95 (hardcover).]

Gavazzi, Stephen M. and E. Gordon Gee. 2018. Land-Grant Universities for the Future. John Hopkins University Press. [ISBN 978-1-4214-2685-3. 202 pages, including index. US$34.95 (hardcover).]

Hanstedt, Paul. 2018. Creating Wicked Students: Designing Courses for a Complex World. Stylus. [ISBN 978-1-6203-6697-4. 180 pages, including index. US$24.95 (softcover).]

Lund, Birthe and Sonja Arndt, eds.. 2019. The Creative University: Contemporary Responses to the Changing Role of the University. Koninklijke Brill. [ISBN 978-9-0043-8412-5. 198 pages. US$55.00 (softcover).]

Warner, John. 2018. Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities. John Hopkins University Press. [ISBN 978-1-4214-2710-2. 273 pages, including index. US$19.95 (hardcover).]

About the Author

Diane Martinez is an associate professor of English at Western Carolina University where she teaches technical and professional writing. She previously worked as a technical writer in engineering, an online writing instructor, and an online writing center specialist. Diane has been with STC since 2005.