doi.org/10.55177/tc710097

By Kristen R. Moore, Timothy R. Amidon, and Michele Simmons

ABSTRACT

Purpose: In this article, we offer a praxis-driven framework that practitioners, scholars, and administrators can use to differentiate between equity and inclusion challenges and move toward catalyzing individual and/or coalitional action. We argue that distinguishing between equity and inclusion as two different potential problem types provides an opportunity for imagining a range of more just and equitable solutions. Acknowledging our margins of maneuverability and tacking in and out of potential realms for action allow practitioners to enact those solutions in practical and context-driven ways.

Method: Following the definitional work of Iris Marion Young (1990) and Rebecca Walton, Kristen Moore, and Natasha Jones (2019) surrounding justice, we delineate relationships between justice, equity, and inclusion before offering a four-step process that practitioners, scholars, and administrators can deploy in order to envision and enact contextually specific tactical actions to redress inequity and exclusion in TPC workplaces and programs.

Results: Through the application of the four-step process to contextualized examples of equity and inclusion challenges, we illustrate the utility of this approach as an actionable strategy for revealing and addressing inequity and exclusion within TPC workplaces and programs.

Conclusion: The work of doing equity and inclusion is an ongoing endeavor that requires vigilance and imagination. Identifying whether we frame a problem as inclusion or equity makes visible the arguments available within specific contexts, acknowledges our margin of maneuverability, and enables us to consider the realm where initial change is possible. Our proposed process provides but one point of entry into the field’s long-standing pursuit of justice.

Keywords: Equity, Inclusion, Social Justice Turn, 4Rs, Margin of Maneuverability

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- A four-step approach to pursuing equity and inclusion as a workplace practice is illustrated and offered.

- By defining equity and inclusion as different aims, practitioners will be better equipped to communicate about and enact equitable and inclusive practices.

- By identifying their margin of maneuverability within the workplace, practitioners can specify whether practices, participatory cultures, processes, or policy are the most advantageous sites for change relative to their aims.

Equity and Inclusion as Workplace Practices

The just use of imagination cannot take up static residence in the heads and hearts of allies and accomplices. The just use of imagination must be transformative.

Dr. Natasha N. Jones & Dr. Miriam F. Williams

Introduction: What Does It Mean to Do Equity and Inclusion in the Workplace?

What does it mean to do equity and inclusion work? To transform our workplaces into sites where all members of our community not only survive but thrive? When Jones and Williams (2020) called for a more just use of imagination, they implored technical and professional communicators to engage in equity and inclusion work as accomplices ready to do the continuous work of recognizing and responding to harms, redressing inequities, and transforming our world(s). We love these ideas, but the work is often mundane: it’s in the details of emails, in the discussions about how to proceed with decisions, in the fourth conversation with a supervisor or chair about the ways inequities have creeped into our hiring practices. These mundane practices comprise equity and inclusion work; yet they are seldom at the center of diversity, equity, inclusion, and access initiatives1 that emerge from our workplaces. Instead, grandiose Equity Plans are rolled out with few details about how to enact them; statements are made about how we support our Black coworkers, but strategies for redressing harms are omitted. This breakdown occurs even in technical communication programs and workplaces across the nation that have adopted social justice frameworks.

Take for example, this situation: a supervisor in the workplace learned that one of the entry-level engineers was repeatedly ignored and dismissed by senior management. This entry-level engineer reported to HR that even in meetings, the senior manager refused to look at them, refused to answer their questions, and left them feeling “defeated and depleted.” Although the entry-level engineer isn’t certain these are about race—he’s Black—it certainly feels like it. When HR reaches out to the supervisor (the engineer has declined to file an official report), the supervisor is not sure what to do and reaches out to the equity and inclusion office for advice: Should the unit work to be more inclusive? Reprimand the supervisor for inequitable treatment? What should happen next?

We consider equity and inclusion breakdowns like this communication design problems that technical communicators with expertise in social justice can address. As diversity, equity, inclusion, and access initiatives emerge across the nation (e.g., DOD, 2022; General Motors, 2022; Ford Foundation, 2022; among many others), technical communicators can and should be leading the mundane communication work required to achieve equity and inclusion. At present, however, too few technical communicators focus on or publish the intentional practices (including tactics, strategies, or rhetorics) necessary for engaging in this work, especially when the work is building arguments that lead to change. For instance, while recently working with a cross-institutional team on an NSF proposal, one of us observed folx who espoused the value of diversity, equity, inclusion, and access but struggled when it came to translating those concepts into structural processes that could engender material change. Similarly, while working with upper administrators to enact equitable policies for students, these administrators often struggled to convey or “message” out on these policies. Consequently, we not only argue that diversity, equity, inclusion, and access needs an action plan (hearkening back to the earlier work of Porter et al., 2000) but also needs tools (hearkening to the more recent work of Walton et al., 2019) that allow us to recognize, reveal, reject, and replace exclusionary, oppressive, and inequitable structures. That is, enacting diversity, equity, inclusion, and access requires sustained, concentrated effort toward planning and enacting change. We sense that most would agree. Still, in our own efforts to pursue diversity, equity, inclusion, and access in workplaces, we’ve found the lack of specificity surrounding how to do this rhetorical work a disorienting and curious omission from the best practices of the field.

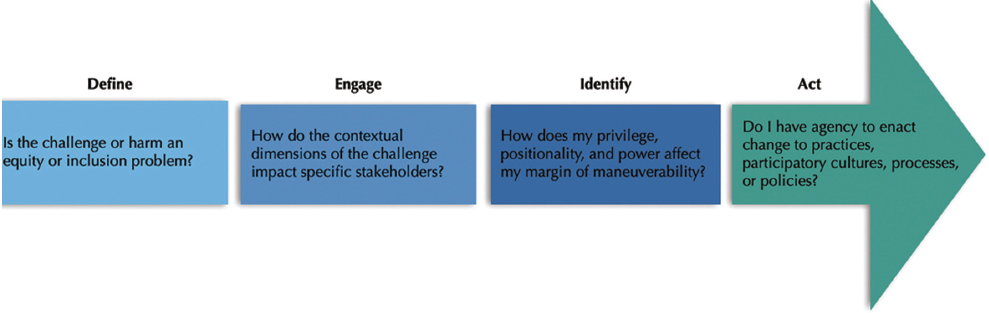

Despite the robust body of scholarship in Technical and Professional Communication (TPC) that has been focused on social justice (Haas & Eble, 2018; Walton et al., 2019; Scott, 2003; Blackmon, 2004; Simmons, 2007; Williams, 2010; Haas, 2012; Edenfield & Ledbetter, 2019; Gonzales, 2018; Opel & Sackey, 2017; Sackey, 2019; Jones & Williams, 2020; Itchuaqiyaq, 2021; McKoy et al., 2022) as well as action scholarship such as the Multiply Marginalized Scholar List (Itchuaqiyaq, 2022), anti-racist scholarly reviewing practices heuristic (2021), Technical Communication Quarterly special issues on Black TPC (2022), the action-oriented ATTW 2022, and the Bibliography of Works by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in Technical and Professional Communication (Sano-Franchini et al., 2022), the field has had limited engagement with diversity, equity, and inclusion as separate, distinct concepts. As such, the clear distinctions among terms and definitions, which are often a mainstay of technical communication, remain limited. In this article, we offer up definitions of two concepts, equity and inclusion, as a means of supporting technical communicators as they enact social justice in productive ways, with a particular focus on how institutional and workplace contexts shape one’s margin of maneuverability, defined as an individual’s ability to navigate situations given their positionality, privilege, and power (Moore et al., 2021). More specifically, we aim to translate theoretical concepts into praxis by offering TPC practitioners a four-step process for moving from deliberation to action—a contextualized roadmap—as it relates to equity and inclusion challenges they are attempting to address in local context:

- Define whether the challenge is best addressed as an equity and/or inclusion problem within a specific context.

- Engage how the challenge affects stakeholders by moving from conceptual “E” equity and “I” inclusion toward contextual “e” equity and “i” inclusion.

- Identify the margin of maneuverability that you possess as an individual and/or member of a coalition to affect change relative to the challenge.

- Act by focusing your individual and/or coalitional labor within a specific realm (practices, participatory culture, process, policy) where you can improve the material conditions for those that are the most marginalized, vulnerable, or harmed by the challenge.

We argue that distinguishing between equity and inclusion as two different potential problem types provides an opportunity for imagining a range of more just solutions. Acknowledging our margins of maneuverability and tacking in and out of potential realms for action allows practitioners to enact those solutions in practical and context-driven ways.

We describe the situation above as fairly straightforward in terms of justice: the supervisor is engaging in microaggressive behavior, causing organizational and individual harm. That is bad. It’s racist. It’s tied to all sorts of cultural norms. Yet, at present, the problem is ill-structured and, for many, addressing it could be overwhelming. Our DEIA approach aims to create some structure for ill-defined equity and inclusion problems.

The opening example is obviously both an equity and inclusion problem. The supervisor’s microaggressive behavior reflects and reifies systems of oppression; it also creates an exclusionary, toxic work environment. Beyond simply naming the behavior as bad (which is limited in its impact) or calling HR to give a boiler plate workshop (probably called “How to be Less Racist, But Only if You Want To”) or to facilitate a brownbag discussion (probably about “Racism is Bad, Have you Heard?”), accomplices and those committed to systemic change have other options for moving to action.

We posit that an accomplice within this workplace could instead approach this problem by defining, structuring, and contextualizing it, and use the DEIA framework to move strategically from an ill-defined problem (Big Jim’s a racist) to a structured problem (Big Jim is enacting inequitable supervisory practices; or Big Jim’s not being inclusive). All of these problems are technically accurate. (Sorry, Big Jim.) But, as we aim to show, the technical description we embrace shifts how we act, the arguments we make, and how we can more effectively deploy them to enact social justice.

We have organized the article in the following fashion. We first define equity and inclusion as concepts and explain how and why they require different arguments: We suggest that by treating them as technically distinct concepts, we can labor with more precision, tactics, and agency toward realizing the aims of justice in TPC contexts. Second, we sketch a four-part process—define, engage, identify, act—and offer a heuristic for applying this process to situated equity and inclusion efforts in workplaces and institutions. Third, we apply the heuristic process to three contextualized examples of equity and inclusion challenges and apply the heuristic/four-step process to each example to articulate how this tool scaffolds the work of moving from approaching equity and inclusion as values or concepts toward contextualized action in one of the realms where TPC practitioners often possess a margin of maneuverability for tactical agency: practices, participatory cultures, processes, policies. We close with an invitation for scholar-practitioners in TPC to not only apply the four-step process, but also share their experiences applying the tool in local contexts, critiquing aspects of its efficacy and usefulness, and/or adapting and building on the process in subsequent work.

Current Approaches to Equity and Inclusion in TPC: A Brief Review Of Literature

As a field, TPC has become increasingly engaged with social justice and diversity, equity, inclusion, and access across a range of topics, including localization (e.g., Lancaster & King, 2021; Smith, 2022; Agbozo, 2022; Shivers-McNair & San Diego, 2017; Gonzales & Turner, 2017), user-experience design (Rivera, 2022; Gonzales, 2018), rhetorics of health and medicine (e.g., Novotny et al., 2022; Manthey et al., 2022; Frost et al., 2021), social justice (Haas & Eble, 2018; Walton et al., 2019; Acharya, 2022), and risk and disaster communication (e.g., Simmons, 2007; Simmons & Grabill, 2007; Haas & Frost, 2017; Banyia, 2022). In a recent issue of TC, for example, Rivera (2022) examined the use of testimonio as a method for attuning to the cultural plurality of places, and Acharya (2022) considered the role an mHealth app in advancing equity and inclusion in the Global South. Indeed, this work engaging equity and inclusion within the field has spanned a considerable depth of contexts and audiences ranging from Smith’s (2022) research to improve usability for aging and elderly populations and Mangum’s (2021) focus on amplifying indigenous voices to Baniya’s (2020) inquiry into disaster response during earthquakes in Nepal and Shivers-McNair and San Diego’s (2017) development of localization practices for collaborating within makerspace communities. These examples are laudable, and we want to take a moment to recognize the crucial (and often painstaking) work that a wide number of scholars have taken in order to engender the “social justice” turn in TPC (Haas & Eble, 2018; Walton et al., 2019).

Still, limitations in our approaches persist, in part because applying diversity, equity, inclusion, and access is hard when we haven’t clearly articulated them as distinct endeavors. Too often, the concepts are conflated and treated as a big tent without the critical attention to their distinct features to make a difference in actual workplace contexts. More specifically, we sense folx struggling to move away from diversity, equity, inclusion, and access as abstract ideas and toward actions that increase justice in workplaces and institutions. We contend, then, that lumping equity and inclusion together limits our ability to move toward action in precise and effective ways. Additionally (or, perhaps as a result), the diversity, equity, inclusion, and access practices written about in publications don’t always directly extend to the various contexts where members of TPC work. For simplicity’s sake, we categorize diversity, equity, inclusion, and access work as either inward facing or outward facing: inward facing diversity, equity, inclusion, and access projects focus on the discipline; outward facing projects focus on the impact of the field on the broader community or industry. We perceive a lack of discussion about how these contexts interrelate and integrate between the approaches TPC has been formulating within scholarship: Can our theories of social justice port into other contexts? Are the approaches to equity and inclusion in TPC applicable in a range of contexts? We think so.

One promising example of scholars connecting the field to broader applications is Sackey’s (2020) work in the context of the design of wearable technologies. He observed that “developers focus more on oversaturated markets filled with mostly young, white, middle-class consumers than the poor or chronically-ill” (p. 33). On one hand, Sackey’s example illustrates an outwardly focused problem with inclusivity in TPC: Design approaches tend to center “normative” user-populations within dominant approaches to design, marginalizing lower-class, BIPOC, poor, disabled, and chronically ill populations by failing to include or consider the ways wearables might respond to needs and challenges of lower-class, BIPOC, poor, disabled, and/or chronically ill populations. On the other hand, Sackey’s example also illustrates an outwardly focused problem of equity in TPC: Design approaches are not simply exclusionary of these populations—the exclusions give rise to inequities in terms of who benefits from wearing such technologies—e.g., the ability to garner personal insights on an individuals’ longitudinal health trends; the ability to receive alerts such as trending toward a high-risk physiological state such as diabetic emergency.

Certainly, Sackey (2020) isn’t the only scholar doing the work to connect the field’s inward-facing social justice and diversity, equity, inclusion, and access initiatives with the more outward-facing impacts. Yet, few scholars begin with this objective in mind; we do. Not enough attention has been paid to how diversity, equity, inclusion, and access, as concepts, offer a range of distinct tactical approaches for addressing injustice in particular contexts.

Defining Terms

In her groundbreaking work on justice and oppression, Iris Marion Young (1990) articulated the strength of differentiating among definitions of justice when she offered a critique of understanding justice through a distributive framework; instead, she outlined a nuanced framework for understanding justice as the counterpart of oppression. Her “Five Faces of Oppression” has served as a foundation for recognizing justice as tied to both equity and inclusion. In defining justice as fundamentally connected to violence, cultural imperialism, marginalization, exploitation, and powerlessness, Young offered a granular distinction among types of exclusion and inequities, giving us the language and strategies for identifying how different practices of oppression make possible and acceptable institutional and individual acts of injustice. She aligned exploitation, marginalization, and powerlessness to relations of power that affect people’s material lives and their access to resources (p. 58). Oppressions such as cultural imperialism, on the other hand, work to exclude nondominant groups, “rendering the particular perspective of one’s own group invisible at the same time as they stereo-type one’s group and mark it out as Other” (p. 59). Justice, she maintains, requires both access to material resources and decision-making as well as a space for difference (p. 61). The differentiation gives Young’s readers (like us) additional strategies for addressing systems of oppression.

We draw inspiration from this definitional approach, as we ask: What strategies for action might emerge if we were to differentiate among these concepts? Or, perhaps even more precisely, we wonder how differentiating from and reorienting to these concepts might open up new opportunities for TPC scholars and practitioners to engage in a “just use of imagination” (Williams & Jones, 2020) within their workplaces. This imaginative work might help us support the larger aims of working toward equity and inclusion in worksites where TPC scholars and practitioners perform labor, author policy, educate students, train the workforce, and/or engage in scholarship.

To address these questions, we’ve turned toward the collaborative work of Walton, Moore, and Jones (2019), which we find particularly valuable for considering distinctions between conceptions of justice (e.g., distributive or procedural justice) and their carry-on implications for equity and inclusion. While discussing procedural justice, for instance, Walton, Moore, and Jones explained that equity must be differentiated from equality in order to achieve justice, as “the sameness required by equality-based perspectives of fairness … cannot help but preserve the status quo, operating as a tool of oppression” (p. 41). Conversely, the authors argued that “equity is relative … [because f]actors such as relative need, relative contribution, and relative levels of oppression may be taken into consideration by equitable procedures and equitable distributions” (p. 41). Indeed, realizing justice-oriented workplaces requires us to go beyond “simply” treating all the same. Instead, equity requires shifting resources (money, power, and positions) relative to the differing and relative levels of privilege, positionality, and power that various individuals and groups possess within our workplaces.

So, what do we mean by equity and inclusion? Certainly, differentiations among equity and inclusion already exist. The “seats at the table” metaphor proliferates to explain diversity, equity, inclusion, and access. Within this metaphor, access emphasizes the structural barriers (e.g., assistive technologies like ramps or elevators may be needed to get to the room where the table is located) that limit the ability of historically marginalized and oppressed groups (HMOGs) from gaining entry to a seat at the table; diversity emphasizes who is present and absent from table (e.g., there are many men, few women, and even fewer BIPOC individuals at the table); inclusion emphasizes whether specific individuals and groups are treated with respect and have a voice for participating in discussions at the table (e.g., women at the table are present, but are repeatedly interrupted or ignored); equity emphasizes whether their opportunities to participate are fair relative to their peers (e.g., men at the table are paid more than women, despite the fact that they are performing the same work at that table). Or, we can look to academic definitions such as Cuyler’s, who defined equity as “fairness in addressing the historic unfairness of [historically marginalized and oppressed groups (HMOGs)]” and inclusion as “belonging, one of many measures of quality of life” (2023, p. 87).

For us, these are good starting places. One of the most significant dimensions affecting equity, as we understand it operating within workplaces, is that inequity catalyzes over time and across locations and systems. For example, Taslimi et al. (2017) demonstrated that equity can be defined in response to a particular crisis, as in disaster response (e.g., Hurricane Katrina), or in anticipation of future problems, as in hazardous materials disposal (e.g., Newport Chemical Weapons Depot). The dynamicity within Taslimi et al.’s approach is particularly crucial for technical communicators building arguments toward equity, which too often gets posited as a steady state goal rather than a responsive and ongoing project. Indeed, Patricia Hill Collins, in Black Feminist Thought, clarified this in her frameworks for articulating power constructs and oppression as shifting and malleable: Activists (and, we will add, technical communicators) can shift power constructs and oppression toward equity. Analogously, whereas equity requires a dynamic focus on the degree of fairness of individuals’ and groups’ relative resources, power, and decision making within and across locations and systems over time, inclusion can require resources and responsive decisions as well as shifts in respect, treatment, and participation that emerge from individual and organizational behavior. Here, we make the, perhaps, obvious point that organizations are comprised of individuals, so organizational efforts toward inclusion that don’t engage individuals or work toward shifting organizational culture are unlikely to be effective. Like equity, inclusion is not a stasis; rather, it’s a repeated activity that seeks to shift traditionally exclusive spaces toward inclusion of those who do not occupy dominant positions. University of Michigan’s Defining DEI suggests that inclusion occurs when “differences are welcomed, different perspectives are respectfully heard and where every individual feels a sense of belonging” (2023). When we have worked toward equity or inclusion, we find the two objectives differ in meaningful ways: Equity prompts us to think about what resources could be shifted in order to provide additional opportunities for marginalized folx to be successful; inclusion prompts us to think about what cultural changes could be made in order to provide marginalized folx with a sense of belonging.

How do TPC practitioners, scholars, and administrators address equity and inclusion within workplaces? Bay (2022) recently argued that one potential action-oriented approach to address these issues is within TPC courses. Centering recent calls from Haas (2020) and Jones and Williams (2020) for the field of TPC to take “explicit action against systemic racism” (Bay, 2022, p. 213), Bay explained that undergraduate courses can have “a broad impact on students … [and] produce lasting impact and transformation toward equity and inclusion” by equipping the next generation of professionals in the field with tools necessary for “creat[ing] more inclusive and equitable workplaces” (p. 214). Thereafter, Bay recognized the groundbreaking work of Shelton (2020), before sketching an assignment within a community-based, service-learning course that called on students to describe how they might promote inclusion within the local community. One particularly valuable aspect of this assignment, from our perspective, is that it emphasized that “issues of inclusion are not abstract concepts but are local, grounded, and applied” (Bay, 2022, pp. 217–218).

We are inspired by this work and other scholars in the field who are pulling the field along a socially just trajectory. Indeed, as practitioners in editorial, administrative, supervisory, and/or mentoring roles, we recognize the promise of differentiated approaches that first specifically target equity or inclusion before turning toward the “local, grounded, and applied” work of contextually redressing those issues (Bay, 2022, p. 218). Once we’ve re-dressed those particular issues, we, then, must recursively reorient to these concepts relative to the issues and contexts within which we are operating. From our experiences, reported here, equity and inclusion are related but different objectives and, as our examples (described below) illustrate, arguments for inclusion and equity comprise different logics and pursue different outcomes. The need for understanding how to structure arguments is great. As Moore et al. (2021) demonstrated, experts in social justice work (broadly construed) often make calculated decisions about what to say, when to say it, and how to say it to particular groups. The “reveal” moment—or when an injustice is discussed, articulated, or conveyed to another—matters. Reveals happen in-the-moment or after-the-fact, depending on the context, and according to Moore et al. (2021), they require a prior recognition that an injustice has occurred. Throughout the zeitgeist, an emphasis on recognizing injustices has been great; yet, the applied work of communicating about, intervening in, and replacing these injustices has been underdiscussed.

Ultimately, we suggest that because equity and inclusion work toward distinct ends they must be differentiated, and/but then, they must be reoriented because these ends work as co-extensive variables affecting the quality of justice in a specific location. From an action perspective, we might work to fix a part of a system to address equity (e.g., we might procure resources that allow us to address gender-inequity in equal-pay for equal-work). However, if we never go back and work toward healing, those people that have been alienated by the system do not have inclusion. Again, these are different objectives and doing work to improve them is laudatory. However, we believe that it is important for TPC to improve the precision through which we address them, as different responsive actions get us to different outcomes in equity or inclusion.

Engaging Concepts within Contexts

In addition to defining terms, the work of equity and inclusion needs to be contextualized in order for individuals to move to action (consult Jones et al., forthcoming). We describe this as moving from Big “E” Equity and Big “I” Inclusion (the abstract concepts) to little “e” equity and little “i” inclusion (what these abstract concepts look like in situ). This indicates the need to move from abstract notions of Equity and Inclusion into the specific contexts of the work. For example, we can posit equity (or inclusion) as our goal and even define it within our institutions, but the specifics of building toward equity within our particular units creates complexity and challenges. If we return to our opening example with Big Jim, we can see how true this is: It might bring about inclusion for the new engineer to fire Big Jim for his microaggressive behavior. Yet, the local policies for hiring and firing make it difficult to imagine a spoken microaggression prompting dismissal.

It’s easy to shy away from a contextual approach because it may yield an incomplete, partial solution: Instead of fixing the whole system, we might be working to shift just one or two particular practices. Although this can feel dissatisfying, we offer it as a practical move that allows us to focus on the moments, locations, and practices where equity and inclusion actually affect our everyday lives. This approach can be generative in helping us to build more effective arguments within workplaces because we have limited margins of maneuverability, including power and resources to affect change (we’ll discuss MoM more in the following section). It also prompts us to engage with a just use of imagination to be more creative in our solutions and more accountable to one another.

Thus, Big “E” equity, for us, often results in an abstraction or a lean toward performativity, whereas little “e” equity, gets at the types of lived experiences and realities that individuals and groups have with equity in their everyday lives in a given institution. Individuals perceive and experience equity through the mundane little “e” aspects of relations, interactions, and moments that comprise our daily lives within workforces and institutions. For the work we do in TPC, we find it less exigent to wade into theoretical discussions about the ontological relationships of E/equity and I/inclusion, as devoting too much effort to a conceptual approach can be used a tactic to obfuscate and obscure our ability to make immediate, contextualized change in locations where equity and inclusion actually matters for those who are marginalized and oppressed within our workplaces. While having a good sense of these concepts is important, as theory and practice are both critical to praxis, we find that, too often, institutional efforts do not meaningfully approach equity and inclusion through the type of fine-grained contextual lens necessary for the generative and imaginative work of challenging and redressing injustices in our workplaces. Flipping from concept to context to focus on e/i can help us envision and prioritize the kinds of solutions and responses that may not be immediately visible when equity and inclusion are considered from a more distant and abstract conceptual perspective.

When Kristen has engaged with faculty, students, and staff in equity and inclusion workshops (and she’s done it a lot), the need to articulate the concept of equity or inclusion is often dwarfed by the context for equity or inclusion, which creates tensions, problems, and pushback that deserve discussion. Stakeholders generally need to understand Equity or Inclusion conceptually before they can apply them; yet, the application of equity or inclusion in context is where the struggle occurs. Partially, of course, this could stem from the fact that it’s possible that it is cognitively and psychologically less face-threatening, rhetorically speaking, for dominant groups to discuss and approach these concepts through the kinds of distance abstraction affords. Yet, we would argue that a focus on the conceptual meaning often defers the actual work of enacting e/i in a localized context where specific people are being oppressed and perpetuating oppression. Thus prompts our aim at a roadmap toward contextualized praxis, toward action.

Identifying our Margin of Maneuverability

Our first two steps: Defining terms and moving them into context allow us to appropriately communicate and set up the problems an institution or workplace faces tied to equity or inclusion, but as we move to action, our possibilities are constrained by our margin of maneuverability. Margin of maneuverability, as Moore et al. (2021, Redressing Inequity) explained, accounts for the relative and dynamic agency we might exercise as actors within a situated moment and place. Possibilities for action emerge from our positionality as well as our relative privilege: We might recognize an inequity in pay for our colleagues (this is actually happening for one of us authors) but our ability to replace that inequity is limited. As such, the work is revealing the problem to folx with a wider margin for action, convincing them to reject the inequitable behavior and work toward change in coalition.

The margin of maneuverability provides a useful framework for decision-making when an individual attempts to address an exclusionary or inequitable practice because (as with the movement from Big “E” to little “e”) it works in practicalities, prompting a technical communicator to acknowledge their own potential for working and strategizing within the context. In short, understanding one’s own margin of maneuverability allows for activists and institutional change-makers to optimize their individual and collective potential. It also allows change-makers to navigate situationally complex systems of inequity because it prompts individuals to seek coalitions for change when their own margin of maneuverability is severely limited when compared to the inequities they seek to address. Within our model (Define, Engage, Identify, and Act), identifying our own margin of maneuverability shapes the next step, wherein we recommend working toward action.

In the opening vignette, the supervisor likely does not have firing and hiring power over the senior engineer; even if he does, he might not be well-positioned to bring that about given the localized context, as we discussed above. Where does their power lie? What are their options? Following a contextual analysis of a harmful situation or event, an actor can assess how their individual and/or collective “privilege, positionality, and power”—what Moore, Walton, and Jones (2021) have described as the 3Ps—might allow for or limit the potential opportunities for action that exist. Through such consideration, individuals may discover that a number of potential avenues for action may exist within their margin of maneuverability, but there may be advantages and disadvantages (particularly risks to oneself or others) associated with various potential avenues within a MoM. Some readers might be thinking, “But isn’t this approach to thinking about MoM an out for folx who simply don’t want to act?” Sure. Those who don’t want to act, won’t. We’re providing MoM as a blueprint or contextualized form of analysis.

We recognize MoM building on the spatial analytics discussed by Porter et al. as an agentive approach for better understanding how power and opportunities for action reside within and between the contextual dimensions of an institution or workplace (2000). In particular, whereas post-modern mapping might help us consider where spatial boundaries exist within and between institutions, MoM considers the opportunities for agency available for individual or coalitional action at particular contextual levels (e.g., classrooms, programs, departments, colleges, universities, corporations, municipalities, states, industries).

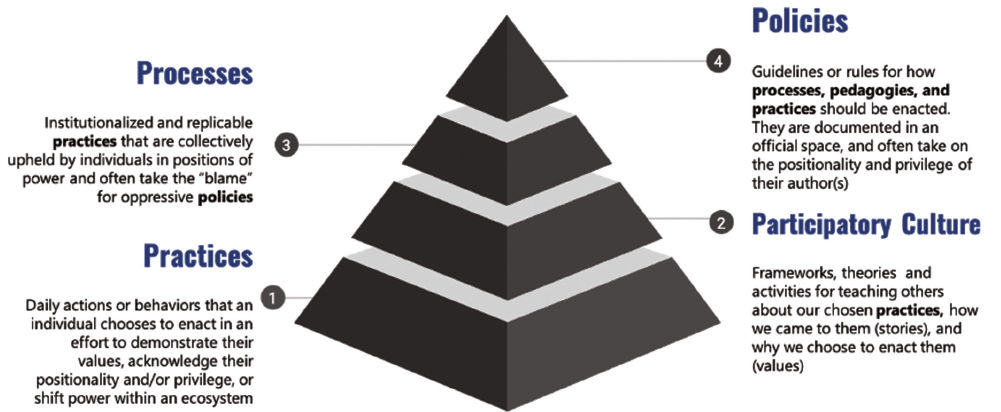

Acting with Purpose

We discern the process of defining, engaging and identifying as iterative, and as we move toward action, the need for working iteratively expands: Where within our context and within our margin of maneuverability can equity or inclusion be most effectively enacted? In our experience, identifying four different realms for enacting change and engaging coalitional work helps to narrow down the immediate next steps for change. Stone and Moore’s (2021) visualization of coalitional action supports this work. As they articulated it, when organizations work toward equity and inclusion, four realms must work in alignment: policy, process, participatory culture (pedagogy), and practices (consult Figure 2). They argued that equitable policy often fails because it lacks processes to uphold them and, as importantly, organizations will implement a policy without considering the pedagogical or participatory activities needed to connect those policies with practices. For instance, one of us works in an organization that recently declared a Safe Learning Environment Policy within its laboratories. Yet, because the policy was declared without accountability processes or trainings to support how we implement the equity-driven policy, practices within the organization have yet to change. Correcting the misalignment of our policies and daily practices requires engaged, coalitional work. In particular, Stone and Moore (2021) identified that breakdowns arise because people don’t often recognize the connections among and/or misalignment between these realms: Simply changing a process means that it just lays on top of the issue–ultimately, we need to work to address practices, participatory cultures, processes, and policy, including how they are related as infrastructures that can support or redress inequity and exclusion within workplaces. Thus, breaking the components down can help us begin to identify where the types of tactical agency to begin building forward momentum can occur!

As technical communicators work to deploy equity or inclusion as workplace practices, these four realms can become sites of inquiry and action, guiding our movement toward equity or inclusion. While Stone and Moore (2021) offered these as mechanisms for coalitional work and organizational alignment, we adapt their four realms as sites for institutional change. Rather than prescribe an approach, our approach invites others into conversation as we understand the work of equity and inclusion as necessarily collective and coalitional. A “paradox of agency,” as Blythe explained, is that it operates within institutions through collective power that “we gain [sic] not by being an autonomous individual, but by being part of something larger, by being part of systems that constrain and enable simultaneously” (2007, p. 173). This paradox is both a pernicious and potentially liberatory dimension of institutions as systems: As agents, we can acquiesce to the status quo, which might perpetuate and maintain injustice within our institutions or we might leverage the impartial power and relative agency within MoM to enact changes (even those that are imperfect) to our institutions.

Our final action-oriented step invites technical communicators to consider how they might enact change, and Stone and Moore’s (2021) framework provides sites of potential change. That is, if the first two steps of our process respectively deal with defining what equity and inclusion challenge we’re dealing with and engaging where the challenge resides as a site for potential redressing exclusion or inequity, and the third step involves identifying our margin of maneuverability based on who we are based on our privilege, positionality, and power, then the fourth step deals with what institutional levers are contextually available to us. If we don’t have maneuverability in one area (perhaps we can’t change a system or a policy), we can use this tool to identify additional paths, including whom we might recruit and mobilize as coalition members. Two points of caution are warranted here: First, that it’s not as simple just picking a realm and working within it. Instead, we suggest that you select a realm where you have maneuverability and then work to build coalitions that can work across the other realms. For example, the White engineer could go directly to management without consent from his peer. Or, he can suggest to his peer that they consider going to the union—that he wants to be an ally and that that means going together and standing together to stand against the continuation of this behavior in the workplace. Second, the margin of maneuverability discussion can become an easy out, especially for those with relative privilege. We adopt Stone and Moore’s framework so to galvanize us to think critically about how many ways we might effect change in our organization.

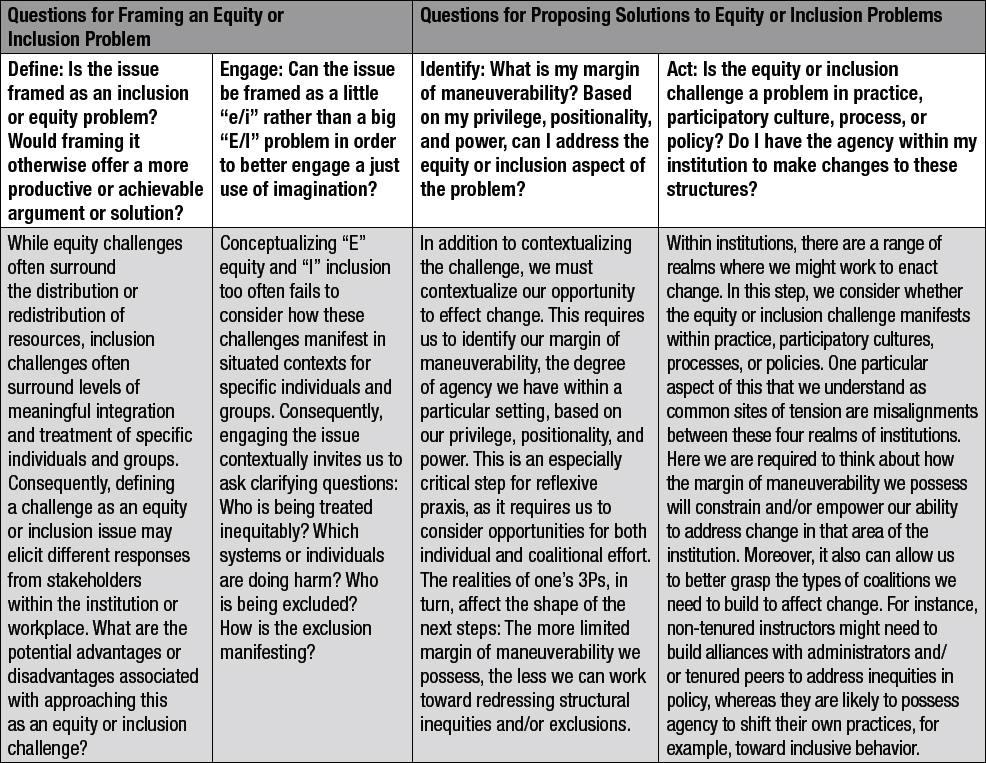

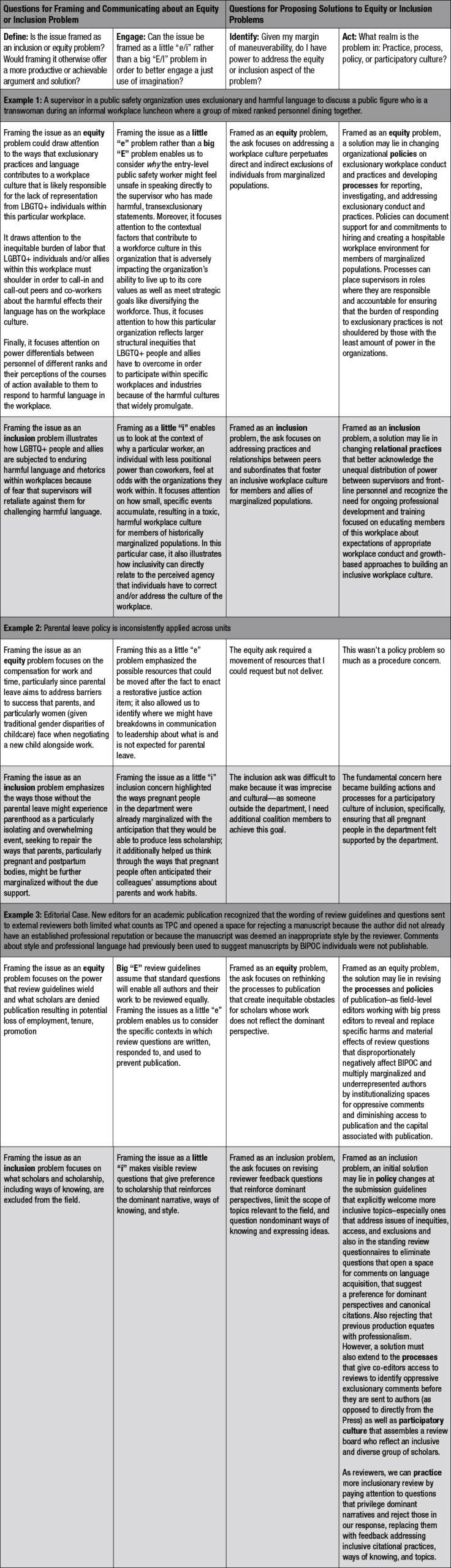

Devising a Plan & Doing the Work

The struggle to do the work of equity and inclusion is, in part, a communication challenge that can usefully be divided into two related areas: Framing the problem and proposing solutions. In Table 1: Framing and Proposing Solutions to Equity and Inclusion Problems (below), we offer heuristic questions that technical communicators can use to scaffold their application of the four-step process to particular equity and inclusion problems growing from situated locations. Next, we sketch three case studies drawn from our experiences within workplaces, including discussion questions that could be used with students in classrooms or professionals in workshops. Thereafter, we apply the four-step process as an analytic, illustrating how the tools help scaffold the work of defining and differentiating between equity and inclusion within a particular event, moving from equity and inclusion as abstract concepts to context-specific challenges that we might take action to address, considering our margin of maneuverability in the situation, and creating an action plan that seeks to address practice, participatory culture, processes, and policy.

This section provides two potential ways of thinking through our heuristic. First, we offer the cases without our analysis and with discussion questions. We imagine that your organization might need opportunities to think through problem-solving when it comes to equity and inclusion. These cases provide a mechanism to facilitate those conversations. Second, in Table 2, we provide our own analysis as a sort of “key” to helping illustrate the way we have used this heuristic to frame and solve equity and inclusion problems.

Example 1 — Misgendering and Transexclusion within a Public Safety Organization

A group of eight public safety professionals, White, working- and middle-class, cis-hetero men, are sitting together at a lunchroom table, sharing a table to celebrate the retirement of a mid-level manager. As a public safety organization, the workplace is organized in a paramilitary format with various workers of varying ranks. The group consists of a manager, two supervisors, two senior-level public safety personnel, and three entry-level public safety personnel. In terms of workplace power dynamics, this is an informal context, where paramilitary protocol is relaxed and members across rank can (mostly) speak freely. However, power differentials continue to play a role in dynamics, as directly challenging individuals at higher ranks is almost commonly coded as insubordination and occasionally met with retaliation. All but two of the workers—one of the supervisors and one entry-level worker—at the table politically identify as Moderate or Conservative.

During the lunch, the discussion swings toward the decision of a neighboring station to temporarily replace the American flag that usually flies behind their apparatus with the Inclusive Pride Flag in order to demonstrate solidarity with members of the LGBTQ+ community during pride month. Although some personnel discuss and complain about the choice that station has made, labeling it as “political,” one of the supervisors makes a pejorative comment about fairness in sports, while misgendering a transathlete that has currently been receiving a significant amount of attention in the news. One of the entry-level personnel looks directly to the other supervisor, who is senior to the other supervisor within the organization, to determine how he will respond to the situation and express his discontent with the statement. The senior supervisor begins to speak up, and the junior supervisor attempts to backtrack his misgendering, stating, “I mean ‘they’,” while looking directly at the entry-level member: “You know, we’re learning and growing and trying to be more inclusive here.” The entry-level member who forwarded the look to the senior-supervisor has sought to educate his coworkers about how such statements cause harm. Although the entry-level member recognizes a level of some growth in the junior supervisor, he still feels an internalized conflict with the alignment of his personal values; the stated core values of the organization, “Service,” “Integrity,” “Respect,” and “Compassion;” and the hostile and exclusionary language directed toward LGBTQ+ people by members of the organization.

Questions for discussion: Do you understand this primarily as an equity or inclusion issue? In what ways does this example reveal conceptual “I”/”E” issues in inclusion/equity? In what ways does this example reveal contextual “i”/”e” issues in inclusion/equity? How do you perceive your margin of maneuverability to respond to this challenge as a senior-supervisor/mid-level manager/another entry-level member of the organization? What realm appears to be the most viable for moving toward enacting change: Specifically, how would you change practice, participatory culture, process, or policy if you sought to address this as an issue of inclusion? Conversely, how might you change practice, participatory culture, process, or policy if you sought to address this as an equity issue? Whom might you seek to enlist as coalitional allies based on your understanding of the dynamics within this workplace context? What might change about your understanding of the dynamics of one of the entry-level personnel was a Black cisgender woman? Or if one of the senior-level personnel was the parent of a transgender child?

Example 2 — Parental Leave Policy

In another TPC program, the university provides parental leave accommodation for birthing parents, offering a full semester off from teaching for the semester nearest to the birth. Despite the provision of this policy, a concern is raised to a program administrator recognized as an equity and inclusion advocate within the department that a pair of eligible instructors have not received leave for recent births. The program director looks into the discrepancy in the implementation of these accommodations and works with instructors—who articulate distinct perspectives on taking advantage of the leave. One of the birthing parents desperately needs the course release, even several years later; the other does not feel it is necessary. Both express concern that the parental leave will be very important for a number of the faculty coming behind them, and they want to be sure there is a culture of acceptance surrounding parental leave. The program director works to develop a restorative response and ensure that both parents are offered after-the-fact amends. When offered, one reiterates that while others might need it, she doesn’t (at least, not at this point).

The equity issue here is, perhaps, obvious: Other birthing parents across the unit receive course releases—but two of them didn’t get that time off from teaching. This is fundamentally inequitable treatment. But if we shift to look at it from an inclusion issue, which is perhaps less obvious in this case, we perceive a need to address the participatory culture as well as the policy and process for implementation. Through a participatory culture lens, the inclusion issues crystallize: Once the parental leave policy (once handled as an individual request or need) becomes part of the organizational culture, parents (especially women, who are often marginalized in the STEM fields) experience not only less resistance to success but an increased sense of belonging. That is, the effect is not only on the individuals affected by this particular example: Future parents enter into the organization and are immediately supported by both the policy and the organizational culture.

It’s worth noting the converse: If one of the parents excused themselves from the “after-the-fact amends” offered, the equity issue would have been addressed at the individual level, but it would have left a potential inclusion issue within the realm of participatory culture. Opting out of the offered leave might have implied that parental leave was only necessary if the parent was not a particularly effective scholar—more of a crutch than an equity-driven policy. This creates a culture of exclusion for those parents who seek and use the parental leave policy. Further, when birthing parents enter an organizational culture that doesn’t evenly implement policies, they risk being ostracized or criticized for their choices to engage. The inclusion solution here required a coalitional action on the part of the parents; the equity solution required a procedural change on the part of the leadership: The parental leave is now publicized and reinforced up the ladder, as well as organizationally.

Questions for Discussion: Do you understand this primarily as an equity or inclusion issue? In what ways does this example reveal conceptual “I”/”E” issues in inclusion/equity? Parental leave policies are already addressing an equity issue. How does the policy breakdown in this case? How do you perceive your own margin of maneuverability to respond to this challenge? What realm seems the most viable for moving toward enacting change: Specifically, how would you change practice, participatory culture, process, or policy if you sought to address this as an inequity issue? Conversely, how might you change practice, participatory culture, process, or policy if you sought to address this as an inclusion issue? Whom might you seek to enlist as coalitional allies?

Example 3 — Editorial Revisions

New editors for a publication recognized that the wording of review guidelines and questions sent to external reviewers both limited what counts as TPC and opened a space for rejecting a manuscript because the author did not already have an established professional reputation or because the manuscript was deemed an inappropriate style by the reviewer. Comments about style and professional language had previously been used to suggest manuscripts by BIPOC individuals were not publishable.

Questions for Discussion: Do you understand this primarily as an equity or inclusion issue? In what ways does this example reveal conceptual “I”/”E” issues in inclusion/equity? How do you perceive your own margin of maneuverability to respond to this challenge? What realm seems the most viable for moving toward enacting change: Specifically, how would you change practice, participatory culture, process, or policy if you sought to address this as an inequity issue? Conversely, how might you change practice, participatory culture, process, or policy if you sought to address this as an inclusion issue? Whom might you seek to enlist as coalitional allies?

Limitations and Conclusion

This study emerged from our own daily practices of doing work toward equity and inclusion. As we worked to imagine new ways forward and navigated our own institutions, we struggled to find published strategies that can be applied in the workplace. This article aims to fill that gap. We conclude with three takeaways that can guide others seeking to enact change in their organizations:

- In communicating the need for change, precise definitions and realms of action are helpful tools for getting work done. Our four-step process is one way of working toward effective communication in equity and inclusion work.

- In imagining how we can work toward justice, we need to consider local contexts in which we enact change, including reflecting on our own margins of maneuverability, identifying potential accomplices and coalition members, and working to address policies, processes, practices and participatory culture.

- Regardless of where and how we begin working to address harm (from an equity or inclusion frame; with policy or process), the work is ongoing, not a steady state.

This article works to delineate a strategy for implementing change, but its limitations are many. First, we haven’t studied the impacts of this approach systematically; designing such a study would be incredibly difficult because inequities emerge constantly and in sensitive contexts. Nonetheless, one of us is working with scholars in systems engineering to establish a model for understanding the impact of these kinds of initiatives. Second, we haven’t discussed the difficulties recognizing injustice in their complexities. It’s worth noting that learning to recognize injustices is a skill worthy of focus. As Moore et al. (2021) reported, recognition accrues over time and through a range of activities, including reading and dialogue. As we gain competency in recognition, though, our best bet is to listen to and honor those who live at the margins. Finally, the examples we offer are limited in their scope and explanation and draw on the experiences of us authors, who occupy positions of relative privilege as White, hetcis, tenured professors. As we begin to enact these steps, more nuanced examples that emerge from other positionalities and vulnerabilities will allow us to refine, critique, and further examine the impact of our heuristic.

References

Acharya, K. R. (2022). Promoting social justice through usability in technical communication: An integrative literature review. Technical Communication, 69(1), 6–26. https://doi.org/10.55177/tc584938

Agboka, G. (2014). Decolonial methodologies: Social justice perspectives in intercultural communication research. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 44, 297–327. https://doi.org/10.2190/TW.44.3

Agboka, G. Y. (2013). Participatory localization: A social justice approach to navigating unenfranchised/disenfranchised cultural sites.Technical Communication Quarterly,22(1), 28–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2013.730966

Agbozo, G. E. (2022). Localization at users’ sites is not enough: GhanaPostGPS and power reticulations in the postcolony. Technical Communication, 69(2), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.55177/tc041879

Anti-racist scholarly reviewing practices: A heuristic for editors, reviewers, and authors. (2021). https://tinyurl.com/reviewheuristic

Baniya, S. (2022). Transnational assemblages in disaster response: Networked communities, technologies, and coalitional actions during global disasters. Technical Communication Quarterly, 31(4), 326–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2022.2034973

Baniya, S. (2020). Managing environmental risks: Rhetorical agency and ecological literacies of women during the Nepal earthquake [Special Issue: Rhetorics and Literacies of Climate Change]. Enculturation, 32. http://enculturation.net/managing_environmental

Bay, J. (2022). Fostering diversity, equity, and inclusion in the technical and professional communication service course. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 65(1), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2021.3137708

Blackmon, S. (2004). Violent networks: Historical access in the composition classroom. JAC, 24(4), 967–972. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20866667

Blythe, S. (2007). Agencies, ecologies, and the mundane artifacts in our midst. In P. Takayoshi & P. Sullivan (Eds.), Labor, writing technologies, and the shaping of composition in the academy (pp. 167−186). Hampton Press.

Cuyler, A. (2023). Access, diversity, equity, and inclusion in cultural organizations: Challenges and opportunities. In A. Rhine & J. Pension (Eds.), Business issues in the arts (pp. 83–104). Routledge.

De Hertogh, B. L., & DeVasto, D. (2020, October). User experience as participatory health communication pedagogy. In Proceedings of the 38th ACM International Conference on Design of Communication (pp. 1–4).

DoD. (2022). Department of Defense Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility Strategic Plan: Fiscal Years 2022–2023. https://media.defense.gov/2022/Sep/30/2003088685/-1/-1/0/DEPARTMENT-OF-DEFENSE-DIVERSITY-EQUITY-INCLUSION-AND-ACCESSIBILITY-STRATEGIC-PLAN.PDF

Eble, M. F. (2020). Transdisciplinary mentoring networks to develop and sustain inclusion in graduate programs. College English, 82(5), 527–535. https://www.proquest.com/openview/7a087e7a86e95f8243863ca3d8dbadf0/1?pqorigsite=gscholar&cbl=42044

Edenfield, A. C., & Ledbetter, L. (2019). Tactical technical communication in communities: Legitimizing community-created user-generated instructions. SIGDOC’19: Proceedings of the 37th ACM International Conference on the Design of Communication (pp. 1–4).

Ford Foundation. (2023). Diversity, equity, and inclusion. https://www.fordfoundation.org/about/people/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/

Frost, E. A., Gonzales, L., Moeller, M. E., Patterson, G., & Shelton, C. D. (2021). Reimagining the boundaries of health and medical discourse in technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(3), 223–229. https://doi./org/10.1080/10572252.2021.1931457

Gates Foundation. (2023). Diversity, equity, and inclusion. https://www.gatesfoundation.org/about/diversity-equity-inclusion

Gutiérrez y Muhs, G., Niemann, Y. F., González, C. G., & Harris, A. P. (2012). Presumed incompetent: The intersections of race and class for women in academia. Utah State University Press.

Guston, D. H. (1999). Stabilizing the boundary between US politics and science: The role of the Office of Technology Transfer as a boundary organization. Social Studies of Science, 29(1), 87–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631299029001004

Guston, D. H. (2001). Boundary organizations in environmental policy and science: An introduction. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 26(4), 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/016224390102600401

General Motors. (2020). The GM Justice and Inclusion Fund. https://www.gm.com/commitments/justice-inclusion-fund

Gonzales, L. (2019). Designing for intersectional, interdependent accessibility: A case study of multilingual technical content creation. Communication Design Quarterly Review, 6(4), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1145/3309589.3309593

Gonzales, L., & Baca, I. (2017). Developing culturally and linguistically diverse online technical communication programs: Emerging frameworks at University of Texas at El Paso. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(3), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2017.1339488

Gonzales, L., & Turner, H. N. (2017). Converging fields, expanding outcomes: Technical communication, translation, and design at a non-profit organization. Technical Communication 64(2), 126–140. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26464442

Gonzales, L. (2018). Sites of Translation: What multilinguals can teach us about digital writing and rhetoric. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv65sx95

Haas, A. M., & Eble, M. F. (2018). Key theoretical frameworks: Teaching technical communication in the Twenty-first century. Utah State University Press.

Haas, A. M. (2012). Race, rhetoric, and technology: A case study of decolonial technical communication theory, methodology, and pedagogy. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 26(3), 277–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651912439539

Haas, A. M., & Frost, E. A. (2017). Toward an apparent decolonial feminist rhetoric of risk. In D. G. Ross (Ed.), Topic-driven environmental rhetoric. Routledge.

Harvard Extension School. (2023). Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging Leadership Graduate Certificate. https://extension.harvard.edu/academics/programs/equity-diversity-inclusion-and-belonging-leadership-graduate-certificate

Hill Collins, P. (1990). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

Itchuaqiyaq, C. U. (2021). Iñupiat ilitquasiat: An Indigenist ethics approach for working with marginalized knowledges in technical communication. In R. Walton & A. Y. Agboka (Eds.), Equipping technical communicators for social justice work: Theories, methodologies, and pedagogies (pp. 33–48). University Press of Colorado.

Itchuaqiyaq, C. U. (2022, March 15). Multiply Marginalized Scholar List. https://www.itchuaqiyaq.com/mmu-scholar-list

Jones, N., Moore, K. R., & Walton, R. Forthcoming. Building inclusive TPC programs: Practical, research-based recommendations. In Technical Writing Program Administration.

Jones, N. N., & Williams, M. F. (2020). The just use of imagination: A call to action. The Association forTeachers of Technical Writing. https://attw.org/blog/the-just-use-of-imagination-a-call-to-action/

Jones, N., Savage, G., & Yu, H. (2014). Tracking our progress: Diversity in technical and professional communication programs.Programmatic Perspectives,6(1), 132-152.

Kim, L., & Lane, L. (2019, October). Dynamic design for technical communication. InProceedings of the 37th ACM International Conference on the Design of Communication(pp. 1–7).

Lancaster, A., & King, C. S. T. (2022). Localized usability and agency in design: Whose voice are we advocating? Technical Communication, 69(4). https://www.stc.org/techcomm/2022/10/28/localized-usability-and-agency-in-design-whose-voice-are-we-advocating/

Mangum, R. (2021). Amplifying Indigenous voices through a community of stories approach. Technical Communication, 68(4), 56–73. https://www.stc.org/techcomm/2021/10/27/amplifying-indigenous-voices-through-a-community-of-stories-approach/

Manthey, K., Novotny, M., & Cox, M. B. (2022). Queering the rhetoric of health and medicine: Bodies, embodiment, and the future. In J. Rhodes, & J. Alexander (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of queer rhetoric (pp. 438–444). Routledge.

McKoy, T. M., Shelton, C. D., Sackey, D. J., Jones, N. N., Haywood, C., Wourman, J. L., & Harper, K. C. (2022). Introduction to special issue: Black technical and professional communication [Special Issue]. Technical Communication Quarterly, 31(3), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2022.2077455

Moore, K. R. (2016). Public engagement in environmental impact studies: A case study of professional communication in transportation planning. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59(3), 245–260. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/7515000

Moore, K. R., Walton, R. & Jones, N. N. (2021). Redressing inequities within our margin of maneuverability: A narrative inquiry study. Proceedings of the ASEE Virtual Annual Conference Content Access (pp. 1–11).

National Science Foundation. (2023a). NSF Supports DEIA.

National Science Foundation. Broader Impacts. (2023b). https://beta.nsf.gov/funding/learn/broader-impacts

National Science Foundation. (2022). Broad Agency Announcement: Regional Innovation Engines. https://sam.gov/opp/68c9f585eed7457a9c1c1fe5dd6ae9a2/view

NASA. (2022). Strategic Plan for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility. https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/nasa_deia_strategic_plan-fy22-fy26-final_tagged.pdf

Novotny, M., DeHertogh, L. B., Arduser, L., Hannah, M. A., Harper, K., Pigg, S., Rysdam, S., Smyser-Fauble, B., Stone, M., & Yam, S. S., (2022). Amplifying rhetoric of reproductive justice within rhetorics of health and medicine. Rhetoric of Health and Medicine, 5(4), 374–402. https://doi.org/10.5744/rhm.2022.5020

Opel, D. S., & Sackey, D. J. (2017). Reciprocity in community-engaged food and environmental justice scholarship. Community Literacy Journal, 14(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.25148/CLJ.14.1.009052

Popham, S. L. (2016). Disempowered minority students: The struggle for power and position in a graduate professional writing program. Programmatic Perspectives, 8(2), 72–95. https://cptsc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/vol8-2.pdf

Porter, J. E., Sullivan, P., Blythe, S., Grabill, J. T., and Miles, E. A. (2000). Institutional critique: A rhetorical methodology for change. College Composition and Communication, 51(4), 610–642. https://doi.org/10.2307/358914

Rivera, Nora. (2022). Understanding agency through testimonios: An Indigenous approach to UX research. Technical Communication, 69(4), 8–26. https://doi.org/10.55177/tc986798

Rose, E. J., & Walton, R. (2015, July). Factors to actors: Implications of posthumanism for social justice work. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual International Conference on the Design of Communication (pp. 1–10). https://doi.org/10.1145/2775441.2775464

Rose, E. J., & Cardinal, A. (2021). Purpose and participation: Heuristics for planning, implementing, and reflecting on social justice work. In R. Walton & G. Y. Agboka (Eds.), Equipping technical communicators for social justice work: Theories, methodologies, and pedagogies (pp. 75–97). Utah State University Press. https://upcolorado.com/utah-state-university-press/item/4001-equipping-technical-communicators-for-social-justice-work

Sackey, D. J. (2020). One-size-fits-none: A heuristic for proactive value sensitive environmental design.Technical Communication Quarterly,29(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2019.1634767

Sánchez, F. (2019). Trans students’ right to their own gender in professional communication courses: A textbook analysis of attire and voice standards in oral presentations. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 49(2), 183–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472816188173

Sano-Franchini, J. (2017). What can Asian eyelids teach us about user experience design? A culturally reflexive framework for UX/I design.Rhetoric, Professional Communication and Globalization,10(1), 27–53. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1064&context=rpcg

Scott, J. B. (2003). Risky rhetoric: AIDS and the cultural practices of HIV testing. Southern Illinois University Press.

Shelton, C. (2019). Shifting out of neutral: Centering difference, bias, and social justice in a business writing course.Technical Communication Quarterly,29(3), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2019.1640287

Shivers-McNair, A., & San Diego, C. (2017). Localizing communities, goals, communication, and inclusion: A collaborative approach. Technical Communication, 64(2), 97–112. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26464440

Simmons, W. M. (2007). Participation and power: Civic discourse in environmental policy decisions. State University of New York Press.

Simmons, M., & Grabill, J. (2007). Toward a civic rhetoric for technologically and scientifically complex places: Invention, performance, and participation. College Composition and Communication, 58(3), 419–448. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20456953

Smith, A. (2022). Everyone is always aging: Glocalizing digital experiences by considering the oldest cohort of users. Technical Communication, 69(4), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.55177/tc674376

Stone, E., & Moore, K. (2022) Illustrating coalitional shifts for socially just design through two case studies. ACM SIGDOC, 2022.

Taslimi, M., Batta, R., & Kwon, C. (2017). A comprehensive modeling framework for hazmat network design, hazmat response team location, and equity of risk. Computers & Operations Research, 79, 119–130. http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~batta/Taslimi%20C&OR%20Paper.pdf

Tham, J. C. K. (2020). Engaging design thinking and making in technical and professional communication pedagogy.Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(4), 392–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2020.1804619

Trauth, E. (2021). “From Homeless to Human Again”: A Teaching Case on an Undergraduate” Tiny Houses and Technical Writing” Course Model. Technical Communication, 68(4), 88–101. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/stc/tc/2021/00000068/00000004/art00007

United States Department of Agriculture. (2022). Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility Strategic Plan Fiscal Year 2022–2026. https://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/usda-deia-strategic-plan.pdf

University of Colorado. Equity Certificate Program. Anchutz Medical Campus. https://www.cuanschutz.edu/offices/diversity-equity-inclusion-community/news-events-and-learning-opportunities/heal-trainings-and-workshops/equity-certificate-program

University of Michigan. (2023). Defining DEI. https://diversity.umich.edu/about/defining-dei/

Visa. (2023). Inclusion + Diversity. https://usa.visa.com/about-visa/diversity-inclusion.html

Walton, R., Moore, K. R., & Jones, N. N. (2019).Technical communication after the social justice turn: Building coalitions for action. Routledge.

The White House. (2021). Executive Order on Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in the Federal Workforce (14035).

Williams, M. F. (2010). From Black codes to recodification: Removing the veil from regulatory writing. Routledge.

Williams, M. F. (2006). Tracing W.E.B. DuBois’ “color line” in government relations. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 26(3), 271–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/10506519211064

Young, I. M. (1990). Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton University Press.

About the Authors

Dr. Kristen R. Moore is an associate professor of technical communication in the Departments of Engineering Education and English at the University at Buffalo. Her research explores the role of technical communication in addressing inequity in the academy and public sphere. Her most recent co-authored book, Technical Communication After the Social Justice Turn, articulates an applied theory of equity and inclusion that she used to enact change. Her scholarship has been published in a range of venues, including the Journal of Business and Technical Communication, Technical Communication Quarterly, Technical Communication and Social Justice, Technical Communication, and IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication.

Dr. Timothy R. Amidon is an associate professor of digital rhetoric who holds an appointment in the Department of English and the Department of Environmental & Occupational Health in the Colorado School of Public Health at CSU. His research explores the interrelationships of technology, workplace literacy, rhetorics of health and safety, as well as data ownership and human agency. His scholarship has appeared in Communication Design Quarterly, Technical Communication Quarterly, Journal of Business and Technical Communication, Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, and a number of edited collections.

Dr. Michele Simmons is a professor of English, faculty affiliate in the Institute for the Environment and Sustainability, faculty affiliate in Emerging Technology in Business + Design, and former Director of Professional Writing at Miami University. Her research examines the intersections of civic engagement, research methodologies, user experience, and participatory design, and focuses on how communities collaborate across difference to address complex problems for social change. Her scholarship has been published in a range of venues, including Technical Communication Quarterly, the Writing Instructor, Programmatic Perspectives, and numerous edited collections.

1 In this article, we use the full terms diversity, equity, inclusion, and access rather than the acronym DEIA to refer to these ideas as concepts and/or initiatives. This is to avoid confusion with our use of DEIA within this article as an acronym for a four-step process; Define, Engage, Identify, Act; that can be used to move toward action addressing diversity, equity, inclusion, and/or access challenges within workplaces.