By Kristen R. Moore, Texas Tech University

Abstract

Purpose: This article reports on a study of professional public engagement specialists and their practices within one case of transportation planning. This study moves beyond the Environmental Impact Statement to reveal the practices used in making public engagement an inclusive and dialogic (rather than exclusive and one-way) process.

Methods: This qualitative study was conducted over two years and included formal and informal interviews, observations of workplace and public projects, and the collection of project documents.

Results: My findings suggest that technical communicators who hope to implement public engagement function across three different roles within the dialogic public engagement process: participant, facilitator, and designer.

Conclusions: The roles of participant, facilitator, and designer expand the potential of technical communicators and require an attention to understudied skills in the field of technical communication, including listening and interrogating boundaries.

Keywords: Public Engagement, Environmental Impact Statements. Intercultural Communication, Ethnography

Practitioner Takeaways:

- In developing public engagement plans, a focus on dialogue can improve the effectiveness and representativeness of the project.

- Technical communicators must commit to developing new skills in listening and intercultural communication if they are to effectively develop and implement public engagement as part of Environmental Impact Statements (EIS).

Introduction

Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) are reports mandated by law if major changes are to be made to a community or geographic location. EISs have been studied in Technical Communication with varying amounts of critique and support. While the limits of the EIS as a deliberative document are well-studied (Killingsworth & Palmer, 1992; Simmons, 2007; Waddell, 1996), EISs nonetheless report on complex, often technical situations and problems, making them a central genre for technical communication. As reports on decision-making processes, however, EISs provide only a limited perspective since they are often written by subject matter experts to meet governmental mandates. Much more can be understood from Environmental Impact Studies (EIStudies), or the research, discussions, and processes that precede the EIS. In studying the research process related to the EIS, technical communicators can more accurately understand the details of the project and, importantly, begin to see the potential to work towards activist ends that scholars like Simmons (2007), Waddell (1996), and Dayton (2002) seek.

This article draws on field research that investigated one Environmental Impact Study (EIStudy)—not the Statement—in order to suggest strategies technical communicators can use to develop engagement plans that are inclusive of diverse stakeholders and that rely on a dialogic rather than one-way approach to communication. These findings provide details, practices, and steps about public engagement that get obscured or overlooked in the EIS. Specifically, this research exposes the potential roles that technical communicators might play in the development of public engagement plans, which are a required part of the EIStudy. More traditional, text-based studies neglect the important work technical communicators can (and do) undertake as facilitators, participants, and designers of public engagement plans.

In the case I report, the Springdale Corridor Study1 (SCS), the public engagement plan was developed and implemented by VCC Communications, a consulting firm located in a Midwestern city. For two years, I studied the consultants as they worked in communities and in their offices, planning engagement projects, interacting with citizens, designing complex documents, and implementing long-term plans to involve citizens in public decisions. The six consultants and two project managers worked on projects with non-government organizations (NGOs), non-profit organizations, engineering firms, corporations, and local and city governments. In all cases, when they were hired to work on public engagement, they adhered to their shared vision for inclusive, representative and dialogic public engagement. In both my interviews and meetings with the VCC founders and consultants, the notion of public engagement as dialogic was prominent, as they described their interest in using policy-based projects to improve their local communities.

I use this case as a blueprint for understanding the work professional and technical communicators (PTC) do in public engagement planning, specifically as it can demonstrate the role activism might play in daily practices of PTC. This article suggests that technical communicators invested in social justice, public planning projects, and/or the efficacy of Environmental Impact Statements can augment their own public involvement by incorporating dialogic and inclusive practices. I begin by defining the terms public engagement and considering existing scholarship on the term. Then, I articulate the importance of dialogue, a central tenet of Patricia Hill Collins’ (2007) articulation of Black Feminist Theory, in the cases I studied. These two sections serve as a foundation for my central argument: in public engagement projects, technical communicators function as participants, facilitators, and designers of dialogue. These three roles require particular skills sets, some of which are clearly articulated by technical communication literature, some of which are not.

Defining public engagement

Within public planning, public engagement refers specifically to the process through which a group of citizens or community members become involved in a public project. Although the NEPA of 1969 does require public engagement, the specifics of the requirement are limited (78 40 C.F.R. § 1500.2(d).). In a report to Congress on the implementation of the NEPA, Luther (2005) describes the public engagement requirement in this way: “Specifically, agencies are required to provide public notice of NEPA-related hearings, public meetings, and the availability of environmental documents so as to inform public stakeholders that may be interested in or affected by a proposed action” (p. 26). For public planners, carrying out this directive is labeled public engagement, involvement, or participation.

The practitioners I studied specifically define public engagement as “a tool for bringing people together to discuss and resolve public policy issues” (VCC Communications, n.p.); this definition shifts the direction of public engagement as it has been discussed within technical communication. Much (though not all) work surrounding engagement has referenced pedagogical approaches to service-learning and community-based work. In general, this research can be characterized either as efforts to bridge the university and its local community or as responses to an imperative for training students to be civically involved or aware (Blythe, Grabill, & Riley, 2008; Bowdon 2004; Bowdon & Scott, 2003; Dubinsky 2001; Simmons 2010). Technical communication scholars often call this public (or community or civic) engagement (or participation or involvement), but I diverge from these definitions not because they are unimportant, but because practitioners’ frames and understandings of participation, involvement, and/or engagement exist outside of the university and its students. Instead, I turn to scholarly and practitioner work in public planning that has conceptualized public participation akin to the Springdale project I discuss in this article.

Both scholars and practitioners have conceptualized public participation through levels or degrees of citizen participation. The earliest example of this is Arnstein’s (1969) Ladder of Participation, which includes eight stages of participation. Arnstein groups her stages into three categories: nonparticipation (which includes therapy and manipulation), tokenism (including placation, informing, and consultation), and finally citizen power (partnership, delegated power, and citizen control). Arnstein’s foundational work suggests, in line with scholars in technical communication, that power must shift if citizens are going to be actively involved in decisions and planning.

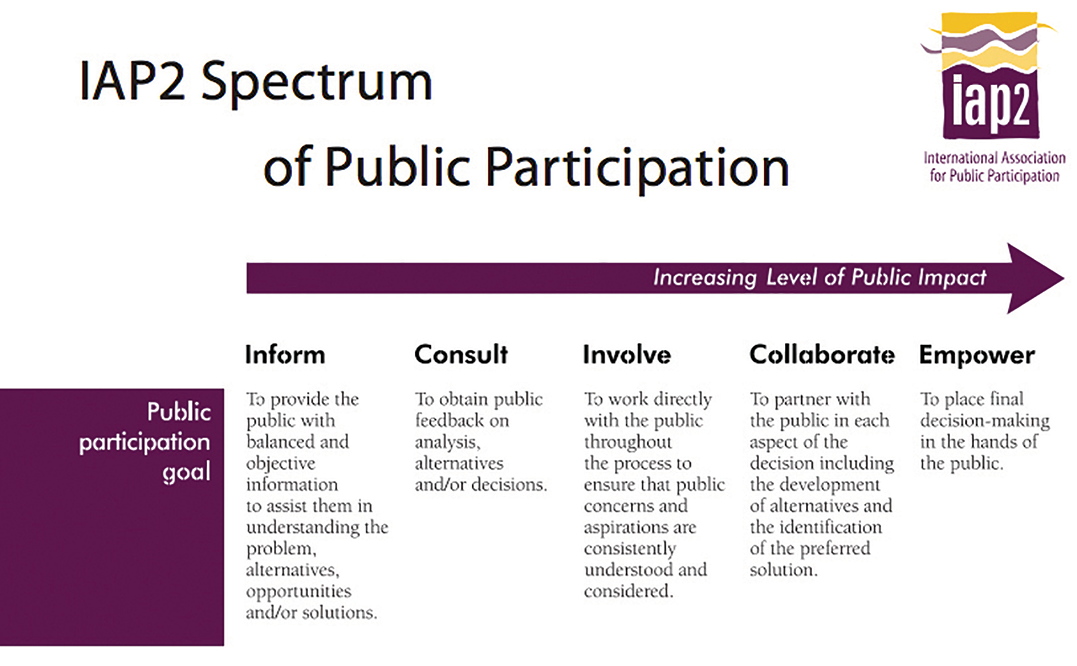

Other models reflect a similar spectrum of engagement, albeit with fewer stages or levels. Lukensmeyer and Torres (2006) suggest public participation extends across four levels: information, consultation, engagement, and collaboration. These four levels graduate in depth of public participation, and the final level “collaboration” represents the ideal participation level because it includes “processes [that] build capacity for lasting cooperation among groups and policy implementation” (p. 17). The International Association of Public Participation (IAP2), a professional organization dedicated to public participation, adds a fifth level of participation, which they term “empowerment.” Empowerment suggests that citizens have power over the decision at hand—that what citizens decide is what will happen.

In practice, these levels get used as conceptual frames for deciding how to proceed in a public engagement plan (see Figure 1). However, for technical communicators, more details are needed in order to effectively implement a public engagement plan.

This article refocuses public engagement as a technical communication practice and explicates how the expert public engagement consultants at VCC implemented their process. I follow previous scholars in discussing steps and practices for involving citizens in public decision-making. In both “Wicked Environmental Problems” (Blythe, Grabill, & Riley, 2008) and “Embracing New Policies” (Williams & James, 2008), for example, the authors report on the role technical communicators can play in implementing public engagement plans. Blythe, Grabill, and Riley report on their role working with community members to help them make and seek knowledge about a dredging project in Harbor, MI. Williams and James report on their role in reaching diverse communities through a public involvement program for the City of Houston’s Bureau of Air Quality Control. These articles demonstrate Simmons’ (2007) claim that technical communicators can and should be involved in developing public participation plans. Like these scholars, I see public engagement as a prime area for technical communicators to work and research because it involves designing documents and processes that help citizens understand the complexities of transportation and urban planning projects. Additionally, as these scholars demonstrate, technical communicators can become citizen advocates, seeking to create more equitable and just decisions about policies and community development.

Unlike these models for studying public policy, however, my research focused on practitioners who enact public engagement projects, an approach that can offer other professional communicators in public projects an alternative view of public engagement. Rather than work with community members or as part of a consultant team, I carefully studied the work of professionals so as to report their strategies back to technical communicators who seek to enter transportation and urban planning vis-à-vis public engagement. Having purposefully divorced the study from university-driven principles or definitions of community or public engagement, I provide a frame for understanding public advocacy within the context of a consulting business.

VCC Communications and the Springdale case

In Springdale, IL, the stakes were high: the Federal Railroad Association’s plans to develop high-speed rail between two metro areas would leave Springdale (the hub between the two metro areas) to absorb the projected 100% increase in the freight and passenger rail by 2020. The city knew that its three current corridors would be inadequate for this increased rail and that reconstruction of one or all of the current corridors would be necessary in order to accommodate the increase. Although Springdale was historically a rail town, its citizens were troubled by the increase in noise, the disruption of traffic patterns, and the potential reification of the racial tensions that had plagued the city for over a century. The city secured an engineering firm (Hendricks Engineering) to complete the EIStudy, and Hendricks, in turn, hired VCC Communications to develop and implement a public engagement plan.

As part of the SCS team, the consultants developed a comprehensive, iterative plan for involving citizens in the EIStudy. Because of the history of racial division in the city, most notably represented by the 10th street corridor, the consultants at VCC knew they needed an inclusive process that could reach as wide a range of citizens as possible. The consultants’ objectives in the Springdale case reflected Simmons’ (2007) and Paretti’s (2003) desire for just and ethical processes, but across their public engagement projects, the consultants confronted the problem that Koch (2013) addresses: institutional processes dictate how flexibly citizens can be integrated into the decision-making structure. In a staff meeting in February of 2010, the VCC consultants mapped their own projects (both past and present) across IAP2’s spectrum of participation (see Figure 1), an activity that helped measure their daily work alongside the professional organization’s recommended framework. Given the bureaucratic complexity of the consultants’ public participation projects—not to mention the financial and time constraints—the project mapping revealed that few of their projects realistically fit into the “empowerment” category because rarely do citizens have control over the final decision.

However, as my study reveals, professional communicators can inch their projects toward more just and equitable decision-making through the design of the engagement plan. In the SCS case and in other cases, the consultants use dialogic and inclusive practices alongside an iterative approach to designing the engagement plans in order to resist the defeatist attitude that might come with limited ability to move the project towards empowerment. In the Springdale Corridor Project, the consultants leaned on dialogues with stakeholders to inform their public engagement plans. This recursive process of continuous refinement existed in tension with the institutional timelines and the financial constraints of the project, so the consultants balanced the maintenance of projected outcomes and schedules alongside the need to accommodate citizen concerns. Their public engagement was founded on the notion that dialogue–both with citizens and among citizens–helps make apparent public concerns that might otherwise be left unseen.

The importance of dialogue has seldom been discussed as an approach to inclusivity in either technical communication or in public planning, and this is perhaps because few practitioners follow what I see as a Black Feminist approach to building their projects. Black Feminist theories2 (while not monolithic) build directly from the daily practices of Black women as they often chip away at issues of social justice through a wide array of daily work in communities, families, and workplaces. The consultants I studied aimed to bring about positive change to their communities and the organizations they worked with through their daily work, and in this way they were admittedly activist in their approach to professional communication. I identify their work as a portrait of Black Feminist activism not simply because the consultants themselves are Black women but also because their commitment to dialogue and inclusivity reflects Patricia Hill Collins’ (2009) articulation of one version of Black Feminism. In Black Feminist Thought, she explains that Black feminists build knowledge from their lived experiences (p. 275-279) and from dialogue (p. 279-284) and they use this knowledge as part of a social justice project that is dedicated to institutional transformation. I saw these foundational tenets of Black feminism enacted at VCC and in the Springdale case. As I have argued elsewhere (Moore, Forthcoming 2018), this approach to knowledge-making particularly ameliorates discussions of public participation, which, in its most just and ethical forms, empowers citizens and invites their lived experiences to affect the project at hand. As such, the theory provides a foundation for prioritizing dialogue in public engagement and for assuming that public engagement rooted in dialogue has the potential for institutional transformation.

Study Design and Data Collection

The Springdale Corridor Study (SCS) was one of three cases of public engagement I studied as part of a workplace ethnography at VCC Communications. My data collection began in the fall of 2009 and extended through early 2012; my methods included daily observations in the office and field, semi-structured interviews with all consultants and project managers, and document collection and analysis. My research on the SCS, specifically, began in February of 2010 before the Notice of Intent—a document that declares the governing body’s intent to conduct an EIS—was released. Within the Springdale community, I attended all of the public open houses, one series of advisory group meetings and a handful of other community events. Within the VCC offices, I attended two formal planning meetings for the project: one with the entire staff of VCC Communications and one with a subset of the staff who were leading the project. I also observed and participated in informal discussions of and planning for the Springdale Project during my three months of daily office observations. During these observations, I took field notes, engaged in informal interviews with team members, and traveled to various out-of-office events, like recording studio sessions, meetings with clients, and luncheons with citizens. Additionally, I collected all documents produced for the Springdale Corridor Project [including earned media] and the results from citizen evaluations and feedback from a number of public events.

Throughout the project, I drew on Black Feminism and critical methodologies to guide my research; as a white woman working among Black women, I took care to mind what Jackie Jones Royster (1996) calls “home training.” She advises that “when you visit other people’s ‘home places,’…you simply cannot go tramping around the house like you own the place, no matter how smart you are, or how much imagination you can muster…” (p. 32). This might seem obvious for qualitative researchers, but in my research, this meant not just being polite—it meant gladly adopting the “resident white girl” position, sharing personal stories during storytelling times at meetings, and adopting the firm’s communal attitude, often rolling up my sleeves to pitch in with work. I sought to support the work of the consultants in whatever ways I could, from taking pictures, to editing documents, to helping consultants learn new technologies. I did so not only because I believe we are ethically bound to enact reciprocity with our participants, but more specifically because culturally that is how VCC did things: everyone together, all hands on deck. I introduce this positioning in part because where the Springdale project certainly introduces issues of voicelessness, justice, and equity, my choice to investigate these consultants was motivated by the fact that Black women in our field have been all but ignored and erased as legitimate practitioners. In order to investigate successfully without co-opting or appropriating their work, I adopted their empathetic and activist, communal and dialogic visions of the world in order to reflect “notions of honor, respect, and good manners across boundaries” with a particular note that the “communities in our nation [that] need to be taken seriously” include Black women technical communicators (Royster, 1996, p. 33).

Dialogic and Inclusive Public Engagement

In the SCS, the consultants used a number of public engagement practices and models that they describe as dialogic (see Table 1 for an overview). When they name their work dialogic, they mean that their practices seek to create two-way communication where all stakeholders of the project (including themselves) both speak and listen. This approach, then, diverges from the one-way communication typically used to engage the public. Often, requirements for public involvement are satisfied by public meetings, in which citizens are invited to listen to engineers or public officials explain what will happen with their cities or communities. As Aleia, one of the consultants working on the SCS said, “We don’t do public meetings. That’s not engagement.” For the VCC consultants, engagement implies a dialogic approach—not the broadcasting of news featured in public meetings.

Table 1 Dialogic Events, Activities and Participants

|

Dialogic Practices |

Dialogic Activity |

Who Dialogued |

|---|---|---|

|

Stakeholder interviews |

VCC consultants interviewed stakeholders |

Consultants [listened] and Stakeholders [spoke] |

|

Informative Communications |

Consultants circulated informative brochures, web material and posted materials on kiosks |

Consultants [spoke] and Stakeholders [listened] |

|

Community Presentations |

VCC consultants attended community group meetings, presented information, and informed citizens about the project; |

Consultants [spoke] and Stakeholders [listened]; Stakeholders [spoke] and Stakeholders and Consultants [listened] |

|

Community Advisory Group Meetings |

Stakeholder groups met to learn about and discuss the project. |

Consultants [spoke] and Stakeholders [listened]; Stakeholders [spoke] and Stakeholders and Consultants [listened] |

|

Public Open Houses |

VCC designed a series of interactive activities; Stakeholders moved through stations that informed them about the projects; Stakeholders asked SMEs about particular elements of the project; Stakeholders posted and read one another’s comments about the project. |

Stakeholders [spoke] and Stakeholders [listened]; SMEs[spoke] and Stakeholders [listened]; Stakeholders [spoke] and SMEs [listened]. |

Brulle (2010) troubles one-way communication in his discussion of messaging campaigns that claim to further citizen interest and involvement. And yet, as Brulle notes of the campaigns he studied, “In place of sustained dialog and interaction between citizens and their leadership, we are offered a one-way communication in which individual citizens are treated as objects of manipulation and control” (p. 89). VCC Communications actively avoids this type of “public relations” or “spin messaging,” as Brulle names it. In fact, the consultants went to great lengths during my ethnographic research to articulate that their work is interested in including more people in decisions–not in managing citizens through mailings and public meetings. In their minds, this kind of public relations runs in direct conflict with their approach to engagement. Merely talking at citizens does not constitute engagement for this organization; engagement works towards dialogue. As I discuss later, technical communicators who aim to engage citizens in ethical and just decision-making projects must develop skills that include listening as well as effective speaking and writing skills.

VCC as participants in dialogue

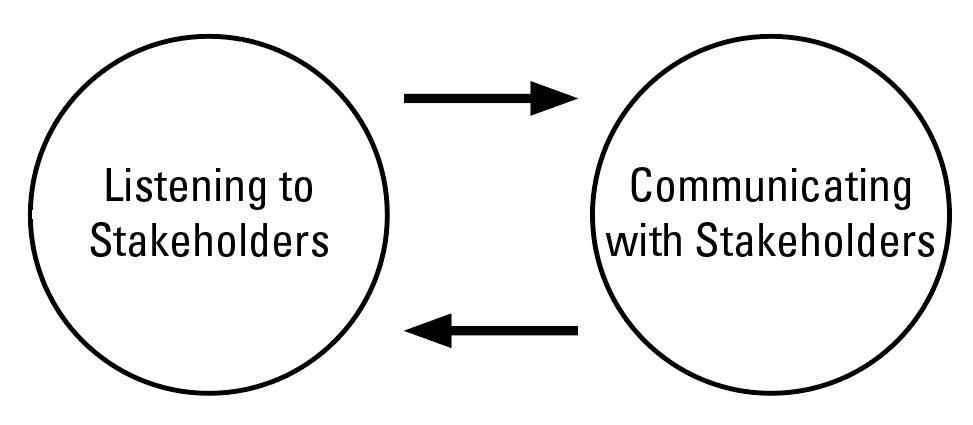

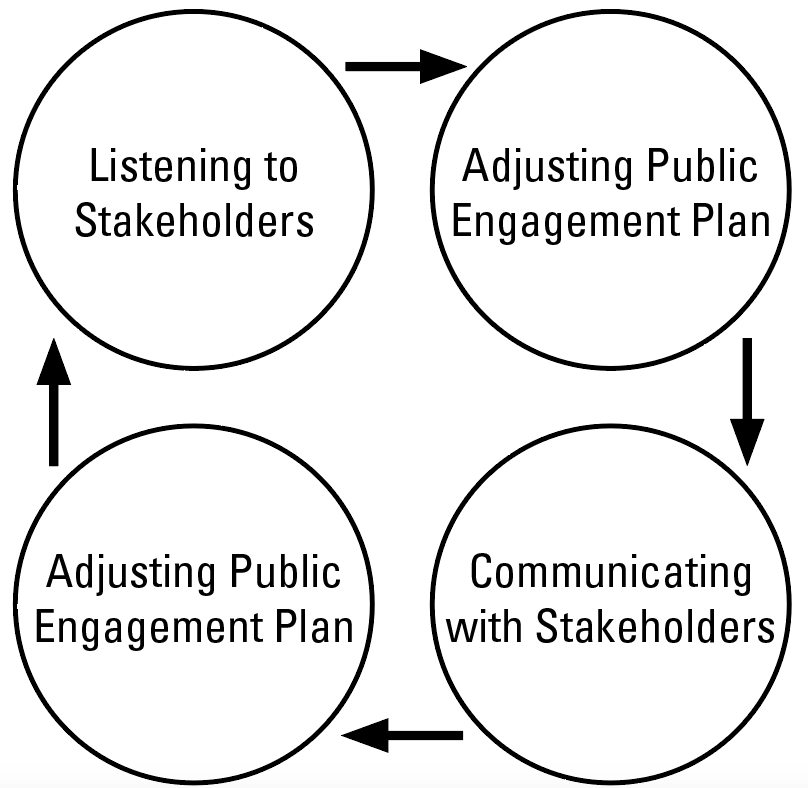

One way to describe these kinds of dialogic practices is through the role the consultants played in dialoguing with citizens and other stakeholders; they both listened to and spoke with citizens. A simple diagram of this might look like Figure 2, where there’s a two-way delivery of information. But, as I’ll describe, the consultants used the information they gained from stakeholders to inform their plan for public engagement—creating an iterative model of dialogue and planning that is much more complicated than the term dialogue initially implies (see Figure 3). Their public engagement planning, then, can be characterized as both flexible and deeply invested in citizen input.

VCC began the SCS with a robust research and listening phase. In Springdale, this phase included interviews with a wide range of stakeholders, including community leaders, residents of various areas of Springdale, public officials, and members of the steering committee. Stakeholder interviews were held at locations of the stakeholders’ choice and, with permission, they were video-recorded and transcribed. These interviews explored stakeholder concerns about the SCS and established the breadth of concerns that the public engagement process would need to address, accommodate, or expose. For example, Drew, owner of Drew Management Services and a member of a citizens’ club, reported his concerns about racial divides, “One of the social issues in the city is whether or not the railroads will divide certain communities from the rest of the city. And that’s a critical concern in the African American community where that has been a historical pattern.” The consultants took note and began anticipating the kinds of struggles facing this particular project, and this initial comment helped the consulting team prepare to take additional steps to demonstrate their sensitivity to racial concerns, which historically had fallen to the wayside in public projects. In addition to structured interviews, they responded to citizen concerns. One of the consultants and several other Steering Committee members spent several hours walking along the 10th Street corridor with citizens that live nearby. They heard the noises of trains and felt the vibrations of the current rail traffic.

The consultants coupled this responsive listening and researching with additional communication that might more aptly be described as the other half of dialogue, speaking. In practice, the work began as informing citizens about the project and circulating key information about it, including the when and where of project events and involvement opportunities. VCC consultants and project managers went to lengths to widely circulate information about the project itself—particularly as the project began. Their informational engagement techniques included a website with comprehensive information about the project, information kiosks at key community locations, bimonthly newsletters to keep citizens apprised of the project, and a Springdale Corridor Study video.

A more concrete form of dialogue occurred through the community presentations that the VCC consultants delivered throughout the SCS. They committed to giving presentations about the SCS to any community group who wanted to know more about it—at the time and location of the group’s choosing. More than 30 times, the VCC Communications team traveled to churches, community centers, neighborhood associations, or small group meetings to discuss the study with citizens, to answer questions, and to clarify the ways that citizens could contribute to the process. Over the course of the project, the consultants gave presentations to and made personal contact with over 1,000 citizens in the Springdale area, demonstrating their personal interest in the citizens by engaging in dialogue with individuals. Because the consultants honored personal experiences and dialogue as meaningful knowledge for the project, the public engagement process not only reached many citizens but also served as a relationship-building process among citizens and between the consultants, SMEs, and citizens.

VCC as facilitators of dialogue among peer stakeholder groups

Although VCC often participated in dialogue (either through the iterative two-way model or through face to face conversations), they also worked to facilitate dialogue among peer groups. In Springdale, I saw this facilitation primarily in the advisory groups, which VCC consultants organized in response to earlier listening in their public engagement planning (see also Moore, 2016). Based upon stakeholder interviews and their knowledge of public engagement, consultants Rose, Aleia, and Lana developed four advisory groups to the Steering Committee: the Medical Advisory Group (MAG), the Community Advisory Group (CAG), the Business Advisory Group (BAG), and the Public Official Advisory Groups (POAG). These groups represented what I call peer stakeholder groups because members of each group had relatively equal position and power in the decision-making process; I differentiate this from cross-level grouping, which might group public officials (who have more relative power in the process) with citizens (who tend to have less). In facilitating these meetings, the consultants were at times participants in dialogue, but they also facilitated dialogic opportunities among stakeholders.

The development and facilitation of the CAG signaled the kinds of cultural difference that needed to be researched and considered in both the final decision and in the development of future engagement events. It included 18 community members, including presidents of neighborhood associations, church leaders, and representatives from other community groups. During each meeting, the advisory groups received updates on the project and were prompted to discuss the updates, to consider the way the new information shaped or changed their views.When I attended one of the Community Advisory Group meetings (CAG), Rose and Leah facilitated the meeting, using a PowerPoint to share new information on the project. The advisory groups provided a chance for conversations across constituents whose primary focus would be the same. Thus, the CAG was primarily responsible for assessing the ways the project would affect communities around Springdale.

Although portions of the CAG meetings focused on questions and answers with the team, the advisory group provided an opportunity for community members to hear, dispute, and discuss differing points of view. The first CAG meeting, particularly, featured a number of disputes wherein community members dialogued with one another; other discussions affirmed and validated the concerns of peer community members. For example, one citizen described,

I worry too about whether or not the outcome of this study is just a foregone conclusion. Maybe it is. But, one of the things I want to do and hope we can do as a community is put some faith in the study and see what the facts tell us. I do hope that no matter what happens, that our participation as neighborhood and community groups will give us a say about what’s best for our city. I am tired of the divisions about who benefits from these major decisions and who doesn’t. The other thing I am nervous about is that the amount of money made available for High Speed Rail is not enough to mitigate its negative impacts. I’m also concerned about having much more freight move through our city.

Where the study team members listened, another citizen listened and then responded:

I too share some of your concerns, particularly the one about there not being enough money.

The public engagement consultants did answer questions in these meetings, but one of their primary roles was to facilitate dialogue among citizens and to allow citizens to share questions and concerns with one another and the study team.

As a further step towards peer dialogue, the CAG functioned as an organizational site for citizen-motivated engagement and dialogue. Members of the CAG took the information they’d obtained from the CAG meetings and circulated that information to other community members. Some members of the CAG went door to door to invite citizens to public events. In this way, the CAGs served as an additional dialogic force for the larger overarching dialogic frame. Not only did CAG members talk with one another, but they communicated the information to local churches, neighborhood groups, and community centers. The engagement efforts of the advisory groups extended another level into the community, as citizens worked outside of the institutionalized structure set up by the consultants.

VCC consultants as designers of dialogue across power levels

In the previous two sections, I’ve discussed dialogue between stakeholders and the consultants and dialogue among peer stakeholders. My study also suggests a third kind of dialogue among stakeholders of differing power levels. This kind of dialogue edges the public engagement process towards the calls from technical communicators like Simmons (2007) and Waddell (1996), who are invested in the efficacy of the public engagement used by governments. In this section, I focus on the two public open houses designed and implemented by the consultants to demonstrate the ways dialogue occurred across power levels.

Two open houses were featured as part of the SCS, and both of them were structured through a series of informative stations, which were set up to cover a particular topic or area of research in the EIStudy. The first open house, for example, had eight stations that covered a range of issues about the project, including details about potential approaches to absorbing the projected rail, and the plan for the EIStudy. In designing the open houses, the consultants insisted that members of the study team attended the entirety of the open house, offering citizens ample opportunity to dialogue directly with subject-matter experts and decision-makers at the open house. Thus, each station was staffed by the engineers, who could speak to the citizens directly and answer questions about the information at that station. For example, one engineer was responsible for researching the vibration and noise pollution that would result at particular crossings; she stood close to the station that covered the potential vibrations so that citizens could ask her directly to clarify a visual or explain the effects of increased rail on their particular residence. Other members of the team wore nametags to indicate that they could answer questions about the project or discuss potential problems or concerns without being tied to a particular station.

In addition to speaking directly to decision-makers, citizens and other stakeholders dialogued through written feedback as well. In the first open house, the VCC consultants developed a public engagement station where citizens were first invited to see the plan for public engagement and then asked to provide feedback about their concerns. The consultants collected information about the concerns of citizens in the form of evaluative questionnaires. Rather than keep those concerns in a box or stuffed in a folder, the citizens were asked to post their comments (with or without their names) on a wall covered with butcher paper, which organized the concerns into areas of concern: 3rd street, 10th street, 19th street, or general concerns. Citizens could write as many concerns down as they wanted, but they were asked to place their comments in the corresponding section to give a visual indication of the geographic location on which citizen concerns and questions were focused.

The public engagement station served to create dialogue in several ways. Most obviously, the citizens communicated with the study team about their concerns and questions—and, in turn, engineers and public officials could (and did) respond, follow up, and ask their own questions. Posting written comments on the wall, a second form of dialogue, was both cross-level dialogue and peer dialogue. In posting their comments, citizens were able to read and respond to one another’s concerns. I observed citizens read the concerns about one of the corridors and then go back to the comment forms to articulate new or different concerns, even after they had already posted concerns. Additionally, public officials and subject matter experts could visually see the concerns about certain corridors stack up, and they were able to read the comments directly from the forms—in the words and writing of the citizens themselves. In all, the consultants gathered 200 written responses to a public input form, which asked citizens to share answers to three questions about their concerns, desires for improvement, and the values that should inform the study. The public input results became motivators for the next phase of the project, and they were presented to all advisory groups, SMEs, and public officials involved in the project.

The public open house structure was designed to encourage dialogue with both SMEs and public officials, who traditionally have more power in these processes than citizens (see Waddell 1996). Because citizens moved through the space on their own and had access to SMEs, they could dialogue directly with individuals making decisions about the project. Although there are limits to this model, this dialogic situation provides an alternative to the kinds of questioning and discussion featured in public meetings. This kind of cross-level dialogue—dialogue between members with different levels of power over the project—occurred in part because the consultants designed a space that allowed for citizens to move through informational displays at their own pace with direct access to the project team along the way. This design privileges citizens as users of the space and prioritizes the ability of these users to determine their own course: the dialogue was on-demand and citizen engagement with decision-makers was immediate and frequent.

VCC consultants as inclusive planners

These efforts to create dialogic engagement (see Table 1) serve as practical steps that technical communicators can take to design opportunities for dialogue among stakeholders in projects like the Springdale Case. However, such efforts fall short of moving public engagement to the realm of what is just and ethical (to borrow Simmons’ terms) if they are not coupled with an inclusive approach to soliciting citizen participation. In other words, even robust dialogue among only elite decision-makers and business owners, for example, does not move public engagement towards just and ethical ends. So technical communicators who hope to adopt dialogic practices must also invest in inclusive practices that tend to citizens’ specific needs. As Rose, one of the principal VCC consultants advises:

Meaningful participation is work enough without adding scheduling, transportation, childcare, learning and language barriers. Convenience is a recognized commodity in virtually every aspect of life and must become so in public decision-making. If we want higher audience attendance and participation, then we must design our outreach processes with our audiences in mind.

She continues, connecting this rhetorical approach of designing for specific audiences to the need for inclusivity:

We must schedule around their availability; choose meeting sites where they live, work and play; ensure that these sites are readily accessible by public transportation; provide child supervision, if requested; and supply food when meeting during meal times. We must also design input processes that respond to their learning styles and education levels and, if necessary, offer language supports for those whose native language is not English. If this seems like a lot of work, thatʼs because it is. However, creating an inclusive environment is essential to counteracting the forces of isolation that habitually undermine public decision-making.

In this section, I provide an overview of three practical and widely applicable strategies for developing inclusive engagement strategies: 1) exhaustive approaches to informing citizens; 2) using multiple modes of interaction; and 3) carefully planned locations and timing for planned events (see also Moore, 2016).

The consulting firm I studied goes to great lengths in their engagement projects (the SCS is no exception) to exhaust their avenues of communication with citizens. In Springdale, this effort began with mailings and the interviews I discuss above. The mailings included a newsletter and a letter, sent to hundreds of Springdale citizens across the city and county. The mailing list included citizen lists secured by collating neighborhood association membership lists, community church membership lists, steering committee suggestions, and stakeholder interviews. The firm aims to make their projects and events inclusive of as many diverse stakeholders as possible and to achieve “representativeness,” which they define as “involving all affected publics.” VCC consultants seek to guarantee that as many views as possible are represented in the final report on the project. As such, the exhaustive mailing list included citizens across the various railways and across the demographic makeup of Springdale, IL. The additional informational, one-way communication I discuss above also sought to reach wide numbers of citizens.

Beyond the exhaustive initial communicative activities that aimed to engage as many citizens as possible, the engagement firm sought to include citizens through multiple media and modes. The media I discuss in the informational communication strategies are quite obviously diverse. For example, the website, which held information about all meetings/events (both how to become involved with the events and what had occurred at those events), was coupled with large kiosks across the city and with print newsletters. These various media aimed to encounter citizens where they would typically find themselves—either at the public library or on the Internet. Beyond a multimedia effort, the consultants insisted that the public open houses provide multiple media for citizens to engage with complex technical material. Citizens could view informational videos and dialogue with engineers to learn more about the project. Many of the “stations” included complex visuals and information, which may have been difficult for some citizens to understand. But those visuals were coupled with interactive maps and opportunities to dialogue with the engineers who made the visuals. These multimedia and multimodal approaches develop inclusivity across learners and citizen concerns. If citizens needed to ask questions about a visual, engineers or other project members were available to answer specific questions. This form of inclusivity moves towards the kinds of inclusivity featured in Universal Design (Center for Universal Design), and it demonstrates the value of inclusivity espoused and enacted by VCC Communications.

Finally, VCC Communication consultants carefully planned their events so as to accommodate as wide a range of schedules as possible. Indeed, many public meetings or engagement events in public planning projects exclude citizens because 1) they are held during times that exclude those that work second-shift jobs, catering instead to white collar workers, whose hours are 9-5 ordinarily, or 2) they’re held at locations that make attendance difficult for particular groups of people. One example of this kind of oversight comes from an urban planning project I researched in West Prairie, TX, where meetings to discuss the future of the city were consistently held between 5:30 and 7:30 pm. In the Springdale case, the consulting firm insisted that public open houses extended from 4 pm to 7 pm – longer than the engineers believed to be necessary but long enough to accommodate citizens with differing schedules. The consultants also developed strategies for engaging citizens in locations and at times most convenient for citizens. The community presentations, for example, were an “on demand” engagement event, where citizen groups, from churches to neighborhood associations to business groups, could request that the consultants (and other steering committee members) attend their already scheduled meetings to report on the status of the Springdale case, answer questions, and receive feedback from citizens about the project. These presentations demonstrate inclusivity through an attention to citizen needs both in terms of location and timing.

Central Skills for Public Enagement

My findings provide an overview of basic public engagement practices (see Table 1) and suggest strategies for enacting these practices in inclusive ways (see Table 2). In addition, these findings provide technical communicators with three different potential roles in dialogic and inclusive technical communication: participant, facilitator, and designer (see Table 3). Perceiving the consultants in these roles can help technical communicators determine their own role in public engagement projects and move public engagement projects toward more just and activist ends. In addition, while I link the import of dialogue at VCC with Black Feminist theory, I want to be clear that anyone invested in positive change—not just Black women or Black feminists—can adopt the strategies enacted by the consultants in my study. But adopting a dialogic approach to public engagement requires a particular set of skills that technical communicators can nurture, invest in, and adopt (See Table 4).

In some ways, Table Four demonstrates the ways technical communicators are already prepared to develop public engagement plans for transportation and urban planning. Indeed, some do (see Blythe, Grabill, & Riley, 2008: Williams & James, 2008). However, the consultants in my study also demonstrated some skills that technical communicators typically do not develop overtly. Although technical communicators openly specialize in and discuss document design, research, and cross-cultural communication, rarely does the importance of listening and of interrogating boundaries, especially as it prepares technical communicators to design dialogues across space and time, come to the fore as central skills. But for the consultants I studied, these skills were central to their ability to function as facilitators, participants, and designers of dialogue with stakeholders. I argue that these skills can augment work we do in the area of public engagement as well as approaches to all areas of technical communication that require collaboration, qualitative research, or interdisciplinary work.

Listening: A technical communication skill

Listening is a central skill for the consultants I studied as they facilitate and engage with dialogue. Throughout my research, I observed the VCC consultants attempt to give voice to those typically unheard, but their public engagement also included revisions of their processes to accommodate citizens. These revisions might be seen as an effort to listen differently—to allow the citizens to dictate how the listening happens. This move echoes Savage’s (2013) call for an increased attention to listening as one approach to more ethical and responsible cross-cultural communication. As part of the larger EIStudy, the firm’s commitment to listening to citizens on their own terms (on their own turf, in their own time) established trust in the process. Hoff-Clausen (2013) ties trust directly to listening in the Danske Bank credit collapse, claiming that “the explicit act of listening contributes to the rebuilding of trust by providing acknowledgement” (p. 433). In Springdale, it was not merely listening that established trust—but listening in ways that reflected the values of the communities they were working with. This is represented by their community presentations, where they listened when and where citizens requested, or by their decision to walk the 10th Street corridor at the request of citizens. In order to develop effective public engagement, then, listening must be tied to actionable outcomes that reflect the values of the communities in which our projects are embedded.

Table 2 Inclusive Best Practices for Public Engagement (Adapted from Moore, 2016)

|

Inclusive Practices |

Central Details |

|---|---|

|

Exhaustive Circulation of Information |

Develop a stakeholder list that casts as wide a range as possible, across geographic location, demographics, and community roles. |

|

Multimodal and Multimedia Engagement |

Create opportunities for engagement across learning styles (including kinesthetic, visual, oral/aural, and linguistic) Use multiple media to communicate stakeholders; don’t assume they’ll prefer digital media. |

|

Scheduling for Diverse Stakeholders |

Consider the living, work, and family situations of potential stakeholders and schedule meetings at convenient locations and times for all stakeholders. |

Table 3 Technical Communicator Role in Dialogic Public Engagement

|

Types of Dialogue |

TCers’ Roles |

Primary Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

|

TCer to Stakeholder |

Participant |

Speak or listen to stakeholders to develop a public engagement plan |

|

Peer Dialogue |

Facilitator |

Prompt citizens to speak or listen with one another—the consultant is present but not the primary speaker or listener |

|

Cross-Power-Level Dialogue |

Designer |

Create situations for dialogue among stakeholders across power levels—the consultant creates activities or designs spaces that prompt stakeholders to speak or listen |

Table 4 Skills and competencies necessary for Technical Communicator’s Role in Dialogic Public Engagement; Bolded items are under-studied in technical communication

|

Role of TCer |

Selected Skills and Competency Required |

|---|---|

|

Participant |

Listening Boundary Work Document Creation Research Cross-Cultural Communication |

|

Facilitator |

Listening Boundary Work Cross-Cultural Communication Public Speaking Leading Discussion/Facilitation |

|

Designer |

Listening Designing Space and Schedules Boundary Work Cross-Cultural Communication Documentation Creation |

Feminist and critical researchers have long seen qualitative research methods as opportunities for giving voice to individuals whose stories, perspectives, or views are typically ignored or left out of important questions. These methods, like the semi-structured interviews used in the Springdale case, are not merely data collection techniques; they can also be reinvented as listening techniques. Put another way, they can be seen as a re-investment in listening. However, such a stance may require, as in the case of the consultants, a commitment to building communities and relationships through these methods. This commitment moves beyond merely seeing the value in others’ stories or perspectives and may require seeing public engagement as what Tuhiwai Smith (2012) describes as “community research” rather than mere person-based research or field research. Critical approaches to person- or field-based research have focused on respect for the individual participant. Community research attempts to validate not just the individual speaking but the community or site of research. This approach to listening moves beyond merely employing qualitative research methods and draws technical communicators into a community advocacy role.

But listening as an engagement strategy is an ecological activity—it requires not just an attention to what is said, but to the site of engagement. VCC’s approach to listening in the SCS (and other cases) depended on their willingness to engage with the city. As I heard the VCC consultants discuss the 10th Street corridor walk, I began to understand that feeling the vibrations, hearing the traffic, and spending time with the city were a part of their engagement process. And they had already engaged with the city in these ways before the citizens requested a corridor walk. In claiming that engagement is ecological, I do not merely mean that it required multiple modes of engagement. I also mean that listening—as seen in VCC’s work—requires putting the claims of all stakeholders in relationship with one another. Rose, one of the consultants, describes this work as intentional listening, wherein listening allows central/main ideas to emerge. These central ideas, of course, are accompanied by some agreement/convergence and some disagreement/divergence, bringing about fresh insights and new ideas. The intentional listening, then, allows for decisions and conclusions to emerge. And so the VCC consultants not only listen to individuals and places, but they also listen for institutional possibilities and community potentials.

Listening, finally, breeds concrete, actionable results. One of the most important lessons learned from VCC’s public engagement process is that listening requires response and action. One claim VCC makes about its public engagement process is that it is results-oriented, and in some ways this claim is market-driven: they tell their clients that their engagement process gets results. But, importantly, in my interviews, three consultants mentioned that one of the most important elements of their engagement work is allowing citizens to see the ways they have been listened to. For example, in Springdale, citizens told the consultants that they wanted Steering Committee members to come see where they lived, and the consultants responded by developing an additional event in the public engagement plan. When citizens suggested one approach to addressing the increased rail might be to take the railroads out of the city center entirely, the project team investigated that alternative and presented the results from their investigation. Moving the railroads outside of the city center entirely proved to be an unfeasible solution (because of the marshy land surrounding the city), but the option was considered and transparently reported on because listening and actionable responses were a priority of the project.

Interrogating boundaries: A technical communication skill

An additional skill employed throughout the dialogic and inclusive engagement process was boundary work—or recognizing where boundaries existed in the project and determining how to produce meaningful dialogue despite these boundaries. According to Wilson and Herndl (2007), boundary work involves interactions that lead to discussion, collaboration, or understanding across boundaries. They draw on Star and Griesemer’s (1989) articulation of boundary object and claim that boundary work focuses specifically on the epistemological differences between groups of scientists, planners, or business owners. Wilson and Herndl see potential for boundary objects to move beyond mere coordination; instead they see boundary work as shifting the stability of boundaries. They explicate how a knowledge map used in a Los Alamos National Laboratory project became an object that “circumvented the experts’ move to demarcate their particular disciplinary or institutional claims as epistemically superior, [and] [b]oundaries became more contingent than abstract and absolute” (p. 147).

In public engagement projects, where the role of both physical and cultural boundaries are so important, boundary work can be considered central to project success. In the Springfield project, the consultants negotiated a host of historical, cultural, economic, and political boundaries; indeed, in dialoguing with stakeholders, facilitating peer stakeholder dialogue, and in designing cross-power-level dialogue, technical communicators are challenged to consider the ways a range of boundaries impact the potential for change in a community. For example, the creation of advisory boards, when considered in terms of boundary work, becomes more than the mundane organization of bodies; instead, the advisory boards can recreate, blur, or reiterate cultural and political boundaries. In light of my findings, I consider Wilson and Herndl’s definition of boundary work, which focuses on epistemological boundaries, too limited to accommodate the kinds of boundary work technical communicators must engage in for public planning. For planning projects, boundary work needs to account for physical boundaries present in transportation and urban planning as well as the more nebulous boundaries that exist because of power differentials.

Porter, Sullivan, Blythe, Grabill, and Miles (2000) articulate the importance of boundary interrogation, which falls under the umbrella of boundary work and more appropriately conceptualizes the boundaries technical communicators must negotiate. Because Porter et al. draw on cultural geographers for their definition, they see the boundaries of institutions as not merely cultural or institutional but also material, allowing for a more literal interpretation of boundary work. Boundary interrogation involves both the rhetorical boundaries created through cultural power structures as well as the material boundaries. Further, they see boundary interrogation as explicitly tied to “the power moves used to maintain or even extend control over boundaries” (p. 624). This makes boundary interrogation a particularly apt conceptualization for the skills VCC consultants use in creating cross-power-level dialogue in public engagement processes. The consultants worked across physical, political, and cultural boundaries to transgress and challenge the traditionally exclusive silos of decision-making in public planning.

The move towards dialogic and inclusive public engagement, then, requires that technical communicators attend to boundary work—both physical boundaries and sociocultural and/or political. In the Springdale Corridor Study, the 10th street train tracks, as an example, created a physical boundary that exists between two cross streets. Although those boundaries could change if citizens decided to start using one of the crossings for new purposes like a rally or sit-in, the regular train schedules limit the possibilities for restructuring that particular boundary. But many citizens also considered it a racial boundary, where the Black community is segregated from the white community. This sociocultural boundary is a less obvious one, wrapped up in over a century of racial tensions. As the consultants found out through dialogue and an investment in understanding citizens’ lived experiences, the boundary has been built through years of disappointment after well-intentioned projects fall flat, disagreement about how to proceed with city planning, and dismissal of the Black community’s concerns. In engaging citizens along the 10th street corridor, as I discussed above, VCC learned to consider this corridor as a double(d) boundary. The ability to see this doubled boundary builds from community listening as well as the acknowledgement of citizens’ lived experiences of the city as racially charged. Layering the physical boundary with the cultural boundaries expressed by citizens shaped the project in meaningful ways, both in how the consultants planned the public engagement events and in how they facilitated dialogue among citizens.

Because boundary work provides an approach to assessing physical and material boundaries, it can also help with a final under-examined skill: designing for schedules and spaces. Given the strong history of user-centered design in technical communication, many citizen-centered approaches to engagement may seem commonsensical. However, designing schedules and spaces for citizens challenges the materials of traditional design. Boundary work can help. For example, Rose suggested we accommodate citizens’ schedules through convenient location, but how did the consultants know to hold CAG meetings at a local church east of the 10th street corridor? Part of these decisions may grow from logical reasoning: some place close to the citizens. But when citizens were coming from around the city, boundary interrogation and work helped the consultants discern that scheduling the meetings west of the 10th street corridor would cause already discouraged and cynical citizens to feel out-of-place and in someone else’s community. Incorporating boundary interrogation into the technical communication skills set can enable citizen advocacy in intentional and ethical ways that are not possible when we ignore the material, rhetorical, and cultural boundaries of a project.

Conclusion and Limits of Study

Ideally, the conclusion of this article would report on the SCS project’s final outcome and provide a neat and tidy epilogue to the data I report here. But, as Lana shared in an interview, transportation planning projects take years—sometimes decades—to come into fruition; indeed, the SCS involved plans for the construction of rail in 2020. At the time of this writing, the SCS project continues to be in the planning phases and VCC continues to engage citizens in discussions of the project. You might be wondering how that could be. In 2011, because of federal funding issues and changes to the long term railroad planning, the SCS project was folded into a larger railway project, truncating the initial plans for public engagement but extending the timeline of rail development projects in Springdale. These unforeseen changes to projects present challenges for technical communicators who pursue ethical and just public engagement: technical communicators ultimately have very little control over the project. But this factor, I think, makes the investment in dialogue, listening, and boundary work of clear import for technical communicators.

This EIStudy reveals the messiness of working towards ethical and just ends within the bounds of an EIS and highlights the messiness of working with citizens on large-scale planning projects. In interviews, both Jocelyn and Rose expressed frustration about the institutional processes that constrain their work, but they suggested that this connection to the government, engineering firms, and other corporate entities that control the projects are not all bad. They reported, in fact, that the painstaking steps of inclusive and dialogic public engagement processes serve as instructive models for NGOs and engineering firms. Both of them spoke of specific cases wherein continued dialogue with firms and organizations resulted in less resistance to public engagement and increased citizen involvement at the decision-making level. In this way, the kinds of institutional transformation pursued by Black feminists can also be adopted by technical communicators who see the need for shifting corporate culture to be accepting of citizen input, open to dialogue as a knowledge-making activity, and engaged with citizens as legitimate participants in public planning.

This study is decidedly limited in its scope—most specifically in its ability to accurately portray the project from citizens’ perspectives. My primary site of study was the VCC firm, and my objective was to learn about their approach to public engagement. This limits the claims I can make about citizen involvement, and it limits my ability to offer often voiceless citizens a voice. Additionally, these findings come from one case of public engagement as enacted by one firm (though many of these practices were mimicked in two other cases I studied). My perspective on the project came from within the public engagement firm, which increases my knowledge of the planning, preparation, and position the consultants took in the cases. At the same time, my focus on the firm excludes robust knowledge about the ways other decision-makers, like Hendricks Engineering or the Federal Railroad Association, viewed the engagement practices.

Even so, the practices that the consultants use in order to further inclusivity can be employed by technical communicators to augment the treatment of citizens in public engagement processes. My findings reveal practices not explicated in the EIS, and they reveal a yet unreported approach to building public engagement around dialogue. The skills, practices, and approaches that VCC Communications enacts in their public engagement planning projects are, I think, widely applicable outside of the specific realm of public planning.

As practitioners increasingly work across cultures and engage with communities unlike their own, principles of dialogue and inclusion can be guideposts for our work. In other words, I argue that technical communicators should participate in, facilitate, and design dialogue whenever we enter communities; practices I report here can be modified or implemented whole piece for a range of community research and corporate projects. Any attempt to plan for future changes can be augmented by incorporating listening and boundary work into our skill sets. That said, in this article, I have only skimmed the surface of discussing the strengths of both listening and boundary work for technical communication, and notably, I provide only a truncated frame for seeing Black Feminism as a practice-based foundation for technical communication. These topics warrant much more research and reflection on their implementation in the workplace. In other words, this article is just one early effort in much larger discussions about what it means to implement ethical, just, and effective technical communication in the public sphere.

References

Arnstein, S. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4):216–224.

Blythe, S., Grabill, J., & Riley, K. (2008). Action research and wicked environmental problems: Exploring appropriate roles for researchers in professional communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 22, 272-298.

Bowdon, M. (2004). Technical communication and the role of the public intellectual: A community HIV-prevention case study. Technical Communication Quarterly, 13(3), 325-340.

Bowdon, M., &. Scott, J.B. (2003). Service learning in technical and professional communication. New York: Longman.

Brulle, R. (2010) From environmental campaigns to advancing the public dialog: Environmental communication for civic engagement. Environmental Communication, 4(1),82-98.

Dayton, D. (2002). Evaluating environmental impact statements as communicative action. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 16(4):355-406.

Dubinsky, J. (2001) Service-learning and community engagement: Bridging school and community through professional writing projects. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED459462.pdf

Herndl, C. & Brown, S. (Ed.). (1996). Green culture: Environmental rhetoric in contemporary America. Madison, WI: U of Wisconsin Press.

Hoff-Clausen, E. (2013). Attributing rhetorical agency in a crisis of trust: Danske Bank’s act of public listening after the credit collapse. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 43(5), 425-448.

Killingsworth, M. J., & Palmer, J. S. (1992). Ecospeak: Rhetoric and environmental politics in America. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois U Press

Koch, P. (2013) Bringing power back in: Collective and deliberative forms of power in public participation. Urban Studies, 50(14), 2976–2992.

Lukensmeyer, C. J., & Torres, L. H. (2006). Public deliberation: A manager’s guide to citizen engagement. IBM Center for the Business of Government Collaboration Series. Retrieved from http://www.businessofgovernment.org/pdfs/LukensmeyerReport.pdf

Luther, L. (2005). The National Environmental Policy Act: Background and implementation. Congress Research Service Report for Congress. Washington DC: Library of Congress. Retrieved from http://nationalaglawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/crs/RL33152.pdf

Moore, K. (2016) A case study of professional communication in transportation planning. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59.3, 245-260

Moore, K. (Forthcoming 2018). Black Feminist Epistemology as a Framework Community-based Teaching. Integrating Theoretical Frameworks for Teaching Technical Communication). Ed. by Angela Haas & Michelle Eble. Utah State University Press. 34 pp.

Paretti, M. C. (2003). Managing nature/empowering decision-makers: A case study of forest management plans. Technical Communication Quarterly, 12(4), 439–459.

Porter, J., Sullivan, P., Blythe, S., Grabill, J., & Miles, L. (2000). Institutional critique: A rhetorical methodology for change. College Composition and Communication, 51(4), 610-642.

Royster, J. J. (1996) When the first voice you hear is not your own. College Composition and Communication, 47(1), 29-40.

Savage, G. (2013, May). Global technical communication: A voice of neo-colonialism or social justice? Paper presented at the Texas Tech University Technical Communication and Rhetoric May Seminar, Lubbock, TX.

Simmons, W. M. (2007). Participation and power. Albany, NY: State U of New York Press.

—. (2010). Encouraging civic engagement through extended community writing projects: Re-writing the curriculum. The Writing Instructor. Retrieved from http://www.writinginstructor.org/simmons-2010-05

Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907-39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3): 387–420.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). London: Zed Books.

Waddell, C. (1996). Saving the great lakes: Public participation in environmental policy. In C. Herndl & S. Brown (Eds.), Green culture: Environmental rhetoric in contemporary America. Madison, WI: U of Wisconsin Press.

Williams, M.F, & James, D.D. (2008). Embracing new policies, technologies, and community partnerships: A case study of the city of Houston’s Bureau of Air Quality Control. Technical Communication Quarterly, 18(1), 82–98.

Wilson, G., & Herndl, C. G. (2007). Boundary objects as rhetorical exigence: Knowledge mapping and interdisciplinary cooperation at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 21(2), 129–154

About the Author

Kristen R. Moore is an assistant professor of Technical Communication and Rhetoric at Texas Tech University. Her research interests include institutional rhetoric and change, cultural rhetorics, and public technical communication with a focus on making public decision-making more representative and equitable. As a founding member of Women in Technical Communication, she also researches feminist mentoring and its potential for advocacy in organizations. Her work has also been published in IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, the Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, the Journal of Business and Technical Communication, and edited collections.

Manuscript received 13 July 2016, revised 1 November 2016; accepted 5 January 2017.

Endnotes

- All city, project, organization, and personal names in this article are pseudonyms, per the author’s IRB protocol. This research was approved by the author’s IRB board in 2009.

- In introducing Black Feminist theory as a frame for dialogic public engagement, I risk oversimplifying the theory for audiences who have little exposure to it and, further, I risk suggesting that we can borrow or co-opt theoretical positions from marginalized groups without careful and thorough positioning. I more fully discuss the foundations of Black Feminist theory and my own positioning in a forthcoming chapter, but in this piece, rather than Whitewash the article, I honor the theoretical underpinnings of the argument I’m building by 1) openly connecting daily practices of Black women with the theories that have been developed from them, 2) integrating these theories without drawing away from the practical takeaways from the study to center on race, and 3) offering a portrait of Black women as technical communicators that might take baby steps towards integrating alternative theories into the field.