By Jeremy Rosselot-Merritt

Abstract

Purpose: In this paper, I discuss contemporary perspectives on the professionalization and legitimacy of technical and professional communication (TPC) as a field and describe results of an interview-based pilot study based in modified grounded theory. The purpose is to study perceptions of TPC and communication practice, particularly as those perceptions relate to professionalization and legitimacy of TPC as a field.

Method: The method of data collection is the semi-structured interview. In the study, I interviewed 14 participants in diverse industries about formal communications produced by their organizations, their perceptions of technical communication practice, and the possibility that their organizations will hire a technical communicator in the future. I then used a modified grounded theory approach to data analysis: one cycle of structural coding, a second cycle of pattern coding.

Results: Analysis of data suggests that, despite the importance of communication in organizations, perceptions of TPC as a field are variable and, though participants demonstrate a basic understanding of TPC practice, their perceptions are often incomplete, not reflecting the range of capabilities that TPC professionals often possess.

Conclusions: This pilot study suggests that challenges to the professionalization and legitimacy of TPC continue to exist. Addressing these challenges will require continuing alignment of academic and practical perspectives on the field, as well as continued work to promote TPC’s value in a range of workplace settings.

Keywords: professionalization, legitimacy, power, academic, practical

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

Study findings suggest that TPC as a field continues to face challenges to professionalization and legitimacy.

Perceptions of the field among non-TPC professionals are accurate on a basic level, but not on a level conducive to optimal use of and interaction with TPC professionals.

There are notable obstacles to expanded use of technical communicators in many workplace settings.

Technical communicators need

more training on organizational dynamics and on how to assert their value in the workplace.

Continued research on aligning academic and practical perspectives on TPC is needed; to help direct that research, continued, regular dialogue is needed between academic researchers and TPC professionals in industry.

Introduction

As a technical communicator, I have long been interested in what is valued in technical communication practice. This interest followed me from my first position as a technical writer more than 15 years ago to a second position as a communications specialist, then to my master’s coursework in technical and scientific communication, and then through two more positions I held with engineering firms before I decided to pursue a PhD in rhetoric and scientific and technical communication.

When I was a fledgling technical writer, I scarcely knew what a technical writer was. Once I became one, most of what I learned about how to be one came from on-the-job training, thanks to my senior colleagues in technical communication. Yet, both colleagues came into the field through non-traditional paths: one was a former advertising professional who became a technical writer decades later, and one was a graphic artist who came upon her new role when she realized her exceptional skills in Quark Xpress were valuable in helping the company manage its large volume of manuals.

We all arrived in technical communication somewhat unintentionally. A knowledge management scholar may say that we were struggling to codify tacit knowledge into an explicit framework (see, for example, Swan, 2007). This struggle took place while we faced regular challenges from management on the need to have three technical writers and from engineering on the idea that our department should stand alone from theirs because we needed that kind of autonomy in order to represent broad interests of cross-departmental stakeholders and external customers.

Over time, a certain theme became consistent in my experience: What we consider “technical communication practice” varies—not only in how it is considered but also in how it is applied in workplace settings. This variability leads to a broad spectrum of perspectives on how technical communication as a field is valued and, therefore, differences in how decision-makers in organizations decide to handle formal communications. Do they hire a technical communicator to manage communication projects? Do they leave it to the existing staff that (currently) does not include a technical communicator? If they do hire a technical communicator, does their existing staff know what the technical communicator is supposed to be doing—or is capable of doing, for that matter?

To begin addressing these questions, as well as better understanding what is valued in technical communication practice, we have to gain the perspective of working professionals—and not just practicing technical communicators (though we certainly need to talk to them as well). Because of the diversity of locations where technical communication takes place, we need to talk to people in spaces that technical and professional communication (TPC) research does not typically investigate.

Some scholars have taken this approach: for example, interviewing managers to gain insight on perceptions of important skills for practicing technical communicators to have (see Whiteside, 2003); interviewing 11 managers of communication departments to construct a “tapestry of voices,” or a “multilogue” as the authors call it (Stevens & Amidon, 2008, p. 12), on the experiences of managers and the factors that influence those experiences within organizations; and studying engineers whose work often intersected with technical communication (see Winsor, 2003; 2004). More recently, Emily January Petersen (2014) studied the professionalization of women working in professional communication roles from their homes, an “extra-institutional” workspace (p. 278), and Jeremy Cushman (2013; 2016) studied the rhetorical work taking place in an automotive repair shop. In his dissertation, Cushman (2013) argued that technical communication researchers should “continue rethinking definitions of the work we value,” including work that involves “traditional product-based labor” (p. 144).

In a similar fashion, I take a broad view of where technical communication can occur. As a researcher, I locate technical communication in any setting where technical communication practices are happening or can happen. As I will describe later in this paper, these practices may be performed by a TPC professional or a non-TPC professional (or both). In considering technical communication practice, I turn to the definition of technical writer/communicator offered by Henning & Bemer (2016):

Technical writers, also called technical communicators, produce documents in a variety of media to communicate complex and technical information. They employ theories and conventions of communication to develop, gather, and disseminate technical usable information among specific audiences such as customers, designers, and manufacturers. (p. 328)

This definition speaks to the role of technical writer/communicator. I base my approach to defining technical communication practice on Henning and Bemer’s definition because it accounts for “practical skills, conceptual skills, and flexibility” (p. 328) needed to address issues of professionalization and legitimacy in the field. Because I argue in this paper that technical communication practice is also taking place in settings where TPC professionals are not actually employed, I make a rhetorical move of applying this definition to settings where TPC professionals are and are not employed, thus emphasizing the practices taking place within organizational settings rather than the titles of the person performing the practices.

With this broad view of TPC practice, I seek to answer two research questions:

- How do individuals’ and organizations’ perceptions of technical communication practice contribute to legitimacy and professionalization of the field?

- How do organizations with and without technical communicators on staff handle formal communication projects?

In this article, I describe results of a pilot study involving interviews of workplace professionals designed to help answer these questions. I seek to bolster our understanding of workplace perceptions of TPC’s professionalization and legitimacy, as well as to offer an evolving perspective on the power that technical communication has in articulating meaning within organizations and for various stakeholders. To help position my research, I will first discuss some notable challenges that the field faces.

Professionalization, Legitimacy, And the Academy-Practice Gulf In Technical And Professional Communication

Technical and professional communication is arguably a “young” field. TPC developed from engineering education needs in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Connors, 1982) to see its own academic programs in the post-World War II era (Durack, 2003) with a corresponding growth in job opportunities (Adams, 1993). Today, TPC is a strong, established field with a robust job market and numerous baccalaureate, certificate, and graduate academic programs (see, for example, Meloncon & Henschel, 2013). The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that the demand for technical writing will grow 11% between 2016, when 52,400 technical writers were working in industry, and 2026, when 58,100 are projected to be working in the United States. The median annual wage for technical writers was $70,930 in May 2017 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017). Technical communicators have adapted their roles to the changing needs of a knowledge economy where technology and creativity are highly valued, and professional programs in the academy are responding. Clearly, all of this is good news.

Yet there are challenges as well. These include struggles with professionalization and legitimacy, a gulf between academic study and industry practice, and (despite the rosy view offered by the Bureau of Labor Statistics) uncertainty about where the field is headed in the future. Practitioners and academics within TPC have striven to professionalize the discipline: consider, for example, the Technical Communication Body of Knowledge (TCBOK), an effort begun in 2007 to help practitioners “train for and practice within the profession” (TCBOK, 2017; see, also, Coppola & Elliott, 2013). Professional certifications offered through the Society for Technical Communication (STC) give practicing technical communicators the ability to document their knowledge and proficiency (Society for Technical Communication, 2018). Yet TPC faces challenges of identity and visibility that continue today. Part of that challenge exists in the workplace in efforts toward professionalization, legitimacy, and recognition of the field; part of the challenge exists in the lack of consistency between academic and practical goals.

In general, professionalization can be thought of as the development of a field’s professional status, body of knowledge, and ways of being practiced. Previous scholarship has explored this concept, for example, in terms of three different kinds of professionalization (Carliner, 2012). These include formal professionalism, which assumes a structured level of expertise in which certain practitioners can claim expert status and recognized organizations help drive an aspiring discipline to a true status as an occupation; quasiprofessionalization, which emphasizes the roles and identities that people develop irrespective of how or whether those people’s roles and identities are defined by a formal organization; and contraprofessionalization, which encourages alternative paths to using paid professionals.

Each of the three approaches emphasizes different views of professional organizations, bodies of knowledge, formal education, professional events, and certification. In TPC, for example, formal professionalization calls for the structured efforts of organizations like STC, a defined body of knowledge, organized degree programs in the discipline, educational conferences, and recognized certification programs. A quasiprofessional view reduces the emphasis on formal organizations and degree programs, which it sees as optional, and holds knowledge as organically gained and disciplinary identity as individually defined. Finally, to those who think in contraprofessional terms, a structured body of knowledge is limiting and constraining, as is professional certification; in this view, organizations may have networking benefits but can also constrain professionals, and formal education can be useful but is not a substitute for proficiency. Each of these approaches has value; however, their application in TPC is inconsistent.

In TPC, both practitioners and scholars have noted the importance of professional identity and status. For example, Savage and Sullivan (2001) pointed out a consistent theme in practicing writers’ accounts of industry experience: that of “professional status and recognition” for the field (p. xxvi). They wrote: “Beginners are concerned with establishing their own status as professionals, and veterans tell about hard-won battles for professional standards and recognition, fought not simply for their individual careers but for their profession as a whole” (p. xxvi). Rachel Spilka (2002) argued that “to move the field closer to professionalization, technical communicators need to argue a clear vision for the field’s future” (p. 12). In addressing TPC’s development as a profession, Pringle and Williams (2005) asserted that “[t]echnical communication has quite possibly arrived as a profession” and that “technical communication has quite possibly arrived at a point where we are able to articulate a set of professional attitudes and practices that give us a sense of group identity” (p. 369). In addition, calling it “zeitgeist in the age of irony,” Coppola (2012, p. 5) addressed professionalization through a comprehensive literature review and historical analysis in her introduction to a special issue of Technical Communication, citing Evetts’s (2011) sociological analysis of professionalism and Hart-Davidson (2001), Salvo (2006, reviewing Power and Legitimacy in Technical Communication, Volume II), Spinuzzi (2008), and Swarts (2011) as examples of scholars who have identified TPC’s “bypassing” of the “traditional notion of profession to arrive at a completely different view of contemporary professionalization” (p. 1).

In another example, through her thematic analysis of 15 graduate student internship reports, Bloch (2011) asserted that the “professional consciousness” of interns represented in the study sample had “eroded over time,” with many interns feeling that their field was marked with low status in organizations; she then called on interns, faculty members, and industry supervisors alike to take steps to help improve the internship experience and the professionalization of the field as a whole. Professionalization is not simply informal or anecdotal; it is subject to analysis and research, a fact that relates to St.Amant and Meloncon’s (2016b) call to better align practical concerns and research questions. For the practicing technical communicator, professionalization is of particularly great importance in obtaining and keeping gainful employment, and in constructing ethos in their role within an organization. In this way, professionalization is not only a matter of academic inquiry or perceptions within the field of TPC; it is also a matter of what other stakeholders—managers, HR professionals, colleagues, clients, and others—think and “know” about the field.

Closely tied to professional identity is the notion of legitimacy. When one asks if a field is legitimate, the question is about value, permanence, and marketability. For instance, in TPC, the growth of networked communication, the Internet, Web 2.0, and ubiquitous mobile technologies helps create a need for people who can document and describe these technologies in broadly accessible terms (i.e., practicing technical writers) and for people who can research the communicative acts surrounding them (i.e., TPC researchers), enhancing the field’s legitimacy.

Notably, Kynell-Hunt and Savage approached this theme with their edited collections Power and Legitimacy in Technical Communication: The Historical and Contemporary Struggle for Professional Status (2003) and Power and Legitimacy in Technical Communication: Strategies for Professional Status (2004). In volume 1, Savage argued for the professionalization of a field that “lacks the status, legitimacy, and power of mature professions” (p. 1) and “goes beyond identifying characteristic skills and knowledge of the field. It also involves prioritizing such competencies” (p. 3). This prioritization derives from a defined a set of professional values and beliefs. Savage also argued that, in order to expand opportunities for technical communicators to flourish, “alternative sites of practice” (p. 4) must be identified. This call relates indirectly with calls to expand sites of technical communication research as well; one example of this call can be found in Cushman’s (2013; 2015; 2016) aforementioned work on rhetorical moves taking place in an automotive repair shop.

A significant challenge to the professionalization and legitimacy of TPC exists in a gulf between academic theory and industry practice. Several examples of this gulf exist. One can be found in differences in disciplinary emphases resulting in part from differences in goals and reward systems in academic and professional spaces (Kynell & Tebeaux, 2009, citing Gambrell, 1998). Another example can be found in tensions between the academic and industry sides of the field. Blakeslee and Spilka (2004) wrote of an historically “strained” relationship between the academy and industry that derives from practitioners’ belief that academic research is irrelevant to the workplace and academics’ belief that workplace practice is lacking in theoretical foundation, too concerned about practical interests, and (among its practitioners) unwelcoming of academic input (see Moore, 2008, pp. 82–83).

These scholars demonstrate the academy-industry gulf as it plays out occupationally and affectively. More recently, in an introduction to a special issue of Technical Communication, Michael Albers (2016) stated that “[a]cademics’ research is poorly communicated to practitioners. An unsurprising but disconcerting statement, considering that technical communication is inherently practical” (p. 293). He later wrote, “Simultaneously, there is a gulf of communicating practitioner needs to the academics” (p. 293). Albers found that this gulf existed for years (at least since 1995, he mused). St.Amant and Meloncon (2016b) also offered a pragmatic view of this research-practice dichotomy in their Technical Communication article “Reflections on Research: Examining Practitioner Perspectives on the State of Research in Technical Communication.” They noted that, despite this dichotomy, both practitioners and researchers of TPC have a unifying need for research. Cooperation between practitioners and researchers helps the collective body of knowledge to grow—in meaningful ways—and it enhances the legitimacy of the field.

On the whole, therefore, legitimacy can be thought of as an affirmative value placed on the field internally (by practitioners) and externally (by other professionals). Legitimacy derives from professional identity, which derives in large part from a set of competencies. As Carliner (2012) observed, how those competencies and identities are developed varies among different approaches to professionalization. What I am interested in studying is how technical communication as a profession is perceived both within and outside TPC, how those perceptions relate to its perceived legitimacy, and what implications can be drawn from those learnings.

Method

To more fully investigate perceptions of the professionalization and legitimacy of TPC, I conducted a pilot study in which I interviewed 14 non-TPC and TPC professionals about their perceptions of technical and professional communication. I incorporated a theoretical framework based on power and articulation theory that informed question selection and data analysis. The method is the semi-structured interview; data analysis consisted of a modified grounded theory analysis in two passes—a first-pass structural coding, a second-pass pattern coding. The study and its associated recruitment and consent materials have been approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Theoretical Framework: Power and Articulation

In terms of theory, I am bringing to bear an important theme in considering the value of technical communication: power—a term with broad meaning, but one of specific importance in technical communication. In Power and Legitimacy in Technical Communication, volume 1, Jennifer Daryl Slack, Daryl James Miller, and Jeffrey Doak (2003) related communication theory with power. Reviewing three communication models—transmission, translation, and articulation—they first explained the transmission view as simplistic and a view that understands communication as moving from one point to another. In this view, “Power … must be understood as possessed by the sender and measured by the ability of the message to achieve the desired result in the receiver. To communicate is to exercise power” (p. 175). The translation view of communication complicates the transmission view by adding the receiver, who can reconstruct the meaning in their own way. In an articulation model of communication, the view of communication is complicated even more significantly. The articulation view, concerned with “the struggle to articulate and rearticulate meaning and relations of power” (p. 181), “points to the fact that any identity is culturally agreed on or, more accurately, struggled over in ongoing processes of articulation and rearticulation” (p. 184). In addition, articulation theory compels us to reframe how we think of meaning and power:

The concepts of meaning and power are dramatically refigured in articulation theory. Meanings cannot be entities neatly wrapped up and transmitted from sender to receiver, nor can they be two separate moments (meaning 1 contributed by the sender and meaning 2 contributed by the receiver) abstractly negotiated in some sort of circuit. Like any identity, meaning—both instances and the general conception—can be understood as an articulation that moves through ongoing processes of rearticulation. From sender through channels to receivers, each individual, each technology, each medium contributes in the ongoing process of articulating and rearticulating meaning. (Slack, Miller, & Doak, 2003, p. 184)

In Slack, Miller, and Doak’s model of power, imputing authorial power to the technical communicator must extend (but not wholly discard) a transmission view of communication in accurately characterizing the technical communicator’s place in communicative power dynamics. The place of the receiver (translation view) and the movements that take place through articulations and rearticulations in technology and media (articulation view) must also be considered. These articulations and rearticulations must take into consideration cultural factors that bear upon meaning.

Articulation is also addressed by Henning and Bemer (2016). Balancing legitimacy and power in their argument for greater clarity in the functions of technical writing, Henning and Bemer (2016, p. 314) argued that an “articulation of what technical communicators are grants the field power in presenting a united front in the workplace and in explaining work responsibilities. It legitimizes the profession as a whole by giving technical communicators a way to measure themselves (against the definition) to show others (and themselves) the value of what they are accomplishing.” This is an argument that may seem commonsense at first but resonates well with practicing technical communicators who have struggled to articulate their roles (ideal or actual) despite vocal advocacy for their value. The authors also pointed out the multifaceted definition of power itself: It can refer to ability or capacity, influence, or authority. I consider all three as part of the collective construct of power in combination with the articulation view of communication that Slack, Miller, and Doak described because such a concept of power takes into account both its functional and communicative dimensions.

To better understand the potential power of the technical communicator to engage in this articulation scenario, it is important to understand both the potential value of the technical communicator in different workplace settings and articulations of the value of communication by the people with whom technical communicators will potentially work in such diverse settings. In promoting professionalization, scholars have called for constructing a coherent and consistent body of disciplinary knowledge as well as promoting a consistent identity for the field. St.Amant and Meloncon (2016a), for example, addressed this concept directly when they called for unifying scholars behind common research questions and a shared vision of TPC despite its multidisciplinarity: “It is a case of unity equals power,” they wrote (p. 268), and later: “commonality brings not only legitimacy but also power” (p. 268, italics in original) by promoting a shared understanding both within and outside the field. In promoting legitimacy, scholars have called for identifying critical competencies (Carliner, 2001; Hart-Davidson, 2001; Rainey, Turner, & Dayton, 2005; Lanier, 2009) and expanding sites of technical communication practice (Savage, 2003; Cushman, 2013).

Competencies, in large part, allow us to take steps in professionalizing our field; with that professionalization comes legitimacy; with legitimacy comes stability, status, and prestige. In a larger sense, legitimacy promotes power, enabling the technical communicator to become an agent in a complex process of articulation and rearticulation—a person who, given a level of professional understanding and respect, has the capacity both to write and to influence important processes within an organization.

Question Design, Data Collection, and Sampling

In this pilot study, my primary method of data collection was the semi-structured interview. Wengraf (2001) described the semi-structured interview as “designed to have a number of interviewer questions prepared in advance” but with such questions being “sufficiently open that the subsequent questions of the interviewer cannot be planned in advance but must be improvised in a careful and theorized way” (p. 5). This type of interview was suitable for this study because it allowed me to frame questions of particular research interest while allowing for the kind of dialogic improvisation that would permit me as an interviewer to ask for elaboration or clarification on points that came up in different discussions.

Aside from demographic questions, most of the questions I asked in each interview (listed in Appendix A) were designed to help address one (or a combination) of four constructs: articulation in organizational communication processes, professionalization of TPC, legitimacy of TPC, and power. The first construct, how articulation takes place in an organization’s communication processes, was addressed in questions 4, 5, and 6, which deal specifically with formal communications produced by an organization for internal and external audiences. Professionalization and legitimacy of TPC were addressed in questions 7, 8, and 9, which are intended to help characterize each participant’s perception of technical communication and their organization’s apparent openness to hiring a technical communicator in the near future. By assessing responses to questions 4 through 9, I can better understand the functional and communicative dimensions of power in the articulation processes taking place, how a technical communicator does or could fit into those processes, and how perceptions of TPC among working professionals in the study affect the (potential) power that technical communication practice has in those organizations.

As mentioned earlier, I have framed this study as a pilot study, a type that has found considerable relevance in TPC research (see, for example, Gonzales & Zantjer, 2015; Karatsolis et al., 2016; Meloncon, England, & Ilyasova, 2016; Rice-Bailey, 2014; Zhou & Farkas, 2010). As part of their research on the status of contingent faculty in TPC, Meloncon, England, and Ilyasova described the applicability of the pilot study to their work, citing as part of that applicability a piece by van Teijligen and Hundley (2002) entitled “The Importance of Pilot Studies.” This piece is especially helpful in identifying both the utility of the pilot study and the reasons for conducting one. At least four of those reasons are especially applicable to this study: testing the research instrument (in this case, the set of interview questions being used), establishing whether the sampling frame and technique are effective, identifying potential logistical problems with the research protocol, and collecting preliminary data.

The selection and sampling process involved a combination of convenience sampling and snowball sampling (Koerber & McMichael, 2008, citing MacNealy, 1999). The convenience sample emphasizes the convenience of recruiting certain people or groups of people for research. Snowball sampling emphasizes a preexistent connection between researcher and participants.

Previous research in TPC has successfully incorporated these methods of data collection and sampling. Interviews have been used to help illuminate topics related to technical communication practice and industry issues (see, for example, Amidon & Blythe, 2008; Baehr, 2015; Pringle & Williams, 1995; Virtaluoto, Sannino, & Engeström, 2016; Whiteside, 2003; Wilson & Ford, 2003). In one recent exploratory study by Wall and Spinuzzi (2018), semi-structured interviews of nine people in content marketing roles helped provide preliminary insight into the functions of content marketing, the practices and genres associated with it, and how its practitioners assess the effects and success of their efforts. Within TPC-oriented journals over the last ten years, the use of convenience sampling (see, for example, Kumi et al., 2013; Spinuzzi, 2012; Yu, 2008; Zhang & Kitalong, 2015) and snowball sampling (see, for example, Petersen, 2014; Walton, 2013; Yu, 2008) can be observed in multiple studies.

In the case of this study, both types of sampling applied because I recruited both people I identified incidentally (through LinkedIn or a “passing by” interaction) as well as people I knew from previous work experiences. This approach allowed me to engage in conversations with people with whom I share a common schema or base of experience while allowing for opportunities to involve participants from unfamiliar or previously unknown sources. As a researcher, I found this allowance beneficial as it led to a more varied dataset—an allowance consistent with the goal of including diverse workplace settings. In the pilot study, I included both TPC professionals and non-TPC professionals (see the section on Participant Characteristics, Backgrounds, Roles, and Organizational Characteristics for more details) because I wanted to see whether different perceptions of the field and of communicative practice would emerge and what considerations I would need to make as the study expands.

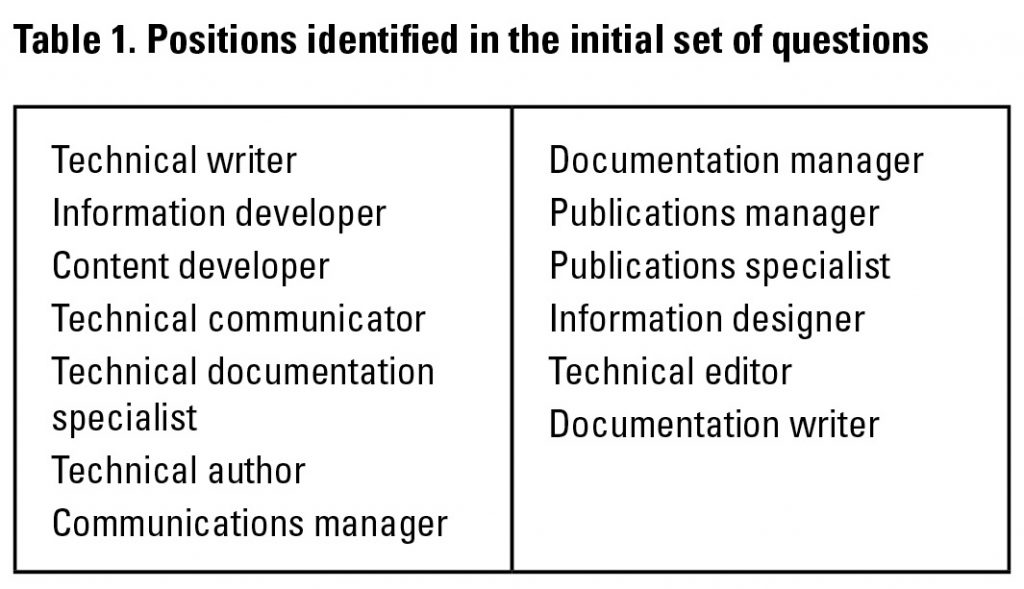

Most of my initial contacts with participants came through LinkedIn or email. If participants expressed an interest, I asked them a set of questions to determine the kind of organization for which they worked (for-profit, non-profit, or otherwise), their familiarity with organizational communications, and whether technical writers and related positions were employed in their employing organizations (see Table 1). The position titles used in the lattermost question derived from Baehr, 2015. If a participant answered that their company employed anyone with these titles, or if the participant was actually a technical writer, I generally invited the participant to continue onto the interview stage, noting that perspective relative to the study goals.

Once formal consent was obtained from a participant, I offered the participant the option of being interviewed in person, in a remote synchronous session (such as Skype), or by email. Because many of the participants were located outside of my primary residential area, many of the interviews took place over email, a method which offered the benefit of convenience to the participant but lacked the dialogic back and forth of synchronous methods. Nonetheless, I was able to gather data and when necessary expand on the base conversation using this method.

In the case of email-based interviews, I copied and pasted the data into a document maintained in a secure repository permitted by the University. In the case of remote synchronous or face-to-face interviews, I recorded the audio with the participant’s permission, converted the audio to a reliable compressed format, and uploaded the file—along with my handwritten notes—to the same secure repository where any email-based interviews are recorded. Only the study supervisor and I had access to the raw data and any personally identifiable information about participants. All data were de-identified in the analysis process.

Data Analysis and Coding Method

I used modified grounded theory as a basis for establishing a theoretical framing for the study data that I obtained. Charmaz (2006) described the grounded theory approach as “methods consist[ing] of systematic, yet flexible guidelines for collecting and analyzing qualitative data to construct theories ‘grounded’ in the data themselves” (p. 2). In this way, the data themselves drove the theoretical development; the conduit for that development was a qualitative coding of the data that I conducted after the interviews were completed.

Analysis of data was primarily textual. To facilitate ease of analysis, I copied and pasted responses from interview questions into an Excel spreadsheet. I then analyzed each response in two coding cycles. In the first cycle, structural coding was applied. In The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, Johnny Saldaña (2009) defined this type of coding as one that “applies a content-based or conceptual phrase representing a topic of inquiry to a segment of data that relates to a specific research question used to frame the interview” (p. 66). In the second cycle, pattern coding was applied. Saldaña (p. 152) cited Miles and Huberman’s (1994, p. 69) definition of pattern codes, which identified them as “explanatory or inferential codes [that] identify an emergent theme, configuration, or explanation.” More specifically, in the first pass, I established these categories of responses based on interview questions: type of company, role, (educational) background, perception, communication types, communication handling, communication effectiveness, and openness to hiring a technical communicator. After each phrase, I added a colon, followed by a qualitative remark that captured the specific characteristic, feeling, or assessment point that the participant reported. Some phrases tended to be simpler than others. For instance, the role was noted exactly as provided by the participant in response to the question about their position; perception, on the other hand, was determined through a combination of direct response and interpretation based on responses to one or more questions. If insufficient data were provided to make a reasonable assessment, that category was noted as “Inconclusive.”

In the second cycle, I examined the data at length, looking for repeated themes from the interviews both in the structural analysis from the first cycle (especially from the perception, communication types, communication handling, and openness to hiring a technical communicator categories) and in the interviews themselves; eventually, I identified several themes that I expound upon in the Analysis and Discussion section below. This is also the part of the process in which I extracted relevant quotations from the interviews.

Analysis and Discussion

In this section, I will discuss the results of qualitative analysis of interview data as I described in the previous section. Of the 14 interviews, 8 were conducted via email, 5 were conducted in person, and 1 was conducted by phone. Due to geographical distance between many of the participants and me, face-to-face interviews were not always feasible; because of scheduling conflicts, in many cases, email became the most efficient way of gathering responses from many of the participants. This method of data collection seemed to work well for nearly all of the participants who participated in this way. Of the challenges I experienced using email (which will be further discussed in the Observed Limitations section below), none of them prevented participants from asking questions or participating if they desired to do so, and none of them prevented me from gathering useful data. In some cases, I did follow up with participants via email in order to clarify specific points—an affordance allowed by the semi-structured nature of the interviews. All of the interviews took place between October 2017 and March 2018. The questions asked of each participant were the same; the interview content then evolved from those questions.

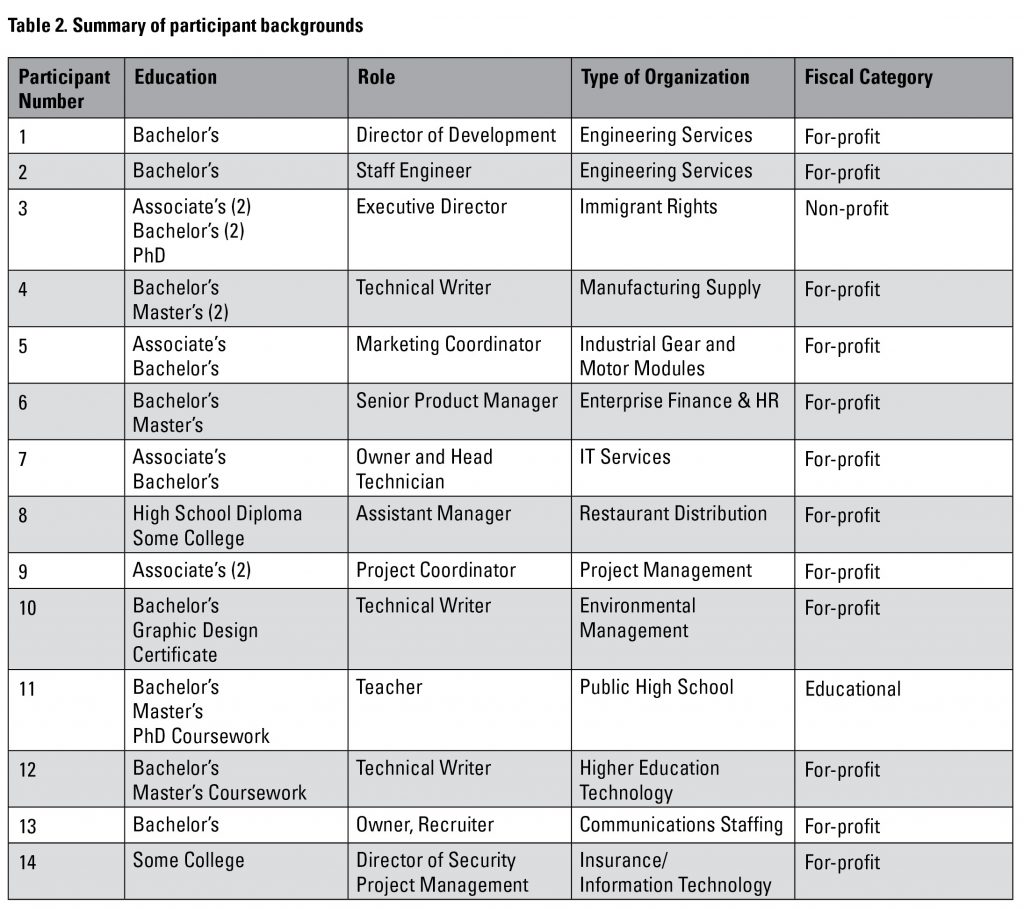

Throughout this section, I will denote specific participants with a numerical identifier (1-14), followed by a three-letter designator indicating whether the person is currently a TPC professional (TPC) or a non-TPC professional (NON). The four TPC professionals include three practicing technical writers (Participants 4, 10, and 12) and the owner of the communications staffing company (Participant 13). The other ten participants are considered non-TPC professionals.

Participant Characteristics, Backgrounds, Roles, and Organizational Characteristics

Participants in the study were from diverse backgrounds. Nine participants were male; five were female. Based on interview results, I determined that eight of the participants held functional, non-management, non-executive roles within their organizations; three worked in management or executive roles, one supervised the activities of students but did not exercise any supervision of her colleagues, and two were owners of a business. 12 worked for organizations based in the American Midwest or with a significant presence in the American Midwest, 1 worked for a company based in the American South, and 1 worked for a company based on the West Coast. All but one worked primarily in offices located in major metropolitan regions (metropolitan statistical areas with populations of 1 million or more).

Of the 14, 3 were full-time technical writers, while 1 had previous technical writing experience although her title and primary job functions were not focused on technical writing. One had been a technical writer previously and now owns a company handling communication placements. Nine of the participants were not technical writers and had no known previous experience in such a role. In terms of educational background, all of the participants had a high school diploma. Ten had at least one bachelor’s degree, one had two associate’s degrees, and two had some college (no degree completed). Four had at least one graduate degree. The degrees represented a broad spectrum of programs, including biology (2), civil engineering, liberal arts, professional writing, business, paralegal studies, management information systems, mechanical engineering, network systems administration, English literature, journalism (2), mass communication, music education, and German studies.

In terms of industries represented, 12 of the participants worked for organizations that fit the study definition of for-profit, 1 worked at a non-profit, and 1 worked for an educational organization. More specifically, the industries represented include the following: IT, Immigrant Rights, Enterprise Finance & HR, Manufacturing Supply, Engineering Services (2), Restaurant Distribution, Project Management, Environmental Management, Industrial Gear and Motor Modules, Public Education, Higher Education Technology, Communications Staffing, and Insurance/IT.

Results of Second-Cycle Coding

As I discussed in Data Analysis and Coding Method, Saldaña (2009) cited Miles and Huberman’s definition of pattern coding as that involving “explanatory or inferential codes, ones that identify an emergent theme, configuration, or explanation” (p. 69, cited in Saldaña, 2009, p. 152). Saldaña also pointed out pattern coding’s suitability for second-cycle coding with the purpose of “development of major themes from the data” (p. 152). I conducted pattern coding with this purpose in mind, specifically focusing on the perception, communication types, communication handling, and openness to hiring a technical communicator categories from structural coding and the interviews themselves. From this process emerged four patterns of interest:

- The need for diversified skills related to communication within organizations and knowledge of organizations themselves

- Varying knowledge of what TPC is

- Commonalities of communication types

within organizations - Reported effectiveness of communications produced by organizations

Patterns 1, 2, and 3 showed evidence of a pattern, but specific supporting examples varied among participants. Pattern 4 showed responses that were more consistent.

Also of interest in the study findings was an additional observation that came up consistently: that participants reported limited openness to hiring a technical communicator in the foreseeable future. I include this observation as a notable result, first, because it did emerge as a consistent finding and has significant ramifications for the use of a technical communicator in those organizations, and, second, because factors contributing to this finding are worth considering both in the study and as part of a larger discussion about the use and marketability of TPC in the workplace. However, because of the multifactorial nature of this phenomenon and the fact that several externalities may influence it, I did not consider it a “pattern” in the way that I considered the other four patterns and, therefore, have included it in this section as an observation.

Pattern 1: The need for diversified skills related to communication within organizations and knowledge of organizations themselves

The need for skill diversification in technical communication practice is not a new theme, and the importance of communication skills within organizations came to light in all 14 of the interviews. Technical communicators have long been asked to extend their roles beyond writing and editing to address organizational needs in project management, customer service, and other areas (see, for example, Amidon & Blythe, 2008; Coppola & Elliott, 2013; Kampf, 2006; Whiteside, 2003).

Findings from this study reinforce that idea—not simply because participants identify it as important in TPC professionals, but more because they identify it as important for themselves and their colleagues, and because skill diversification is an area where technical communicators tend to thrive. In articulation processes within organizations, skill diversification seems to increase the effectiveness of communications and, perhaps just as important, the functional and communicative power that a person has.

For example, Participant 3 [NON], the nonprofit director, reported that she “[wears] many hats” in her role, with duties including “grant research and writing, corporate and individual fundraising, strategic planning, program design and evaluation, web design and marketing, and hiring employees and attracting volunteers.” This “wearing of many hats” affords her the ability both to help articulate meaning in her organization and to occupy a position of power. Participant 14 [NON] reported that management at his company would like the communications specialist in his department to take on diversified roles such as project management; as this happens, the communications specialist will take on expanded roles in multiple articulation scenarios.

As skills go, there is also something to be said about the skill of maintaining cognitive distance from the product or process about which a practicing technical communicator is writing. One of the three practicing technical writers (Participant 4 [TPC]) stated:

It should be noted that I understand very little about the products we make. That is partially because I have no mechanical intelligence, but also because I think it’s very important that I maintain that outsider’s ignorance. It prevents

me from creating a manual that is littered with jargon and shorthand language that the user may not understand.

Yet, this same person reports how important it is to be able to interface with people who have the information he needs: “Sometimes [correcting errors in manuals] requires chasing down someone who knows the details,” he said. “Most people here are good about responding and working with me, but some have to be cornered to get them to pay attention.” This observation leads to an evolving thought that, in a practicing technical communicator, organizational knowledge is just as or more important than product knowledge. Participant 12 [TPC] added an element of organizational culture in her interview, pointing out the “informal and relaxed” nature of her workplace and how that culture impacted internal communication processes. In 64% (9/14) of the interviews, knowledge of the organization was expressed as an important concept. In study terms, organizational knowledge became strongly associated with power and articulation.

Pattern 2: Varying knowledge of what technical communication is

Another finding is the varying, inconsistent, and often incomplete knowledge of what technical communication actually is. This would be a relatively manageable problem if the people managing technical communicators were technical communicators themselves, or if the people hiring them had previous ample training and experience working with technical writers. In a number of cases represented here, this is simply not happening. Participants reported the following thoughts on what technical communication actually involves, grouped into categories of TPC professionals and non-TPC professionals.

TPC Professionals’ Responses

- “Operator instructions and parts manuals” (Participant 10 [TPC])

- “Content experience … [although] labels are changing as the scope of work shifts away from a documentation focus toward a client focus” (Participant 12 [TPC])

- “A more current and updated way of stating my background, which is conventional technical writing … It’s funny how that term technical writer will not die [despite changes in the field since the 1970s].” (Participant 13 [TPC])

Non-TPC Professionals’ Responses

- “How can I communicate pieces of my

business [such as financials] to my audience”

(Participant 1 [NON]) - “Someone who writes user guides and repair manuals… . having knowledge in a technical field as well as communication knowledge… . a hybrid who can accurately simplify complicated information to various audiences” (Participant 3 [NON], who has supervised a group of TPC professionals in the past)

- “Communications about the internal working of our products from an engineering perspective” (Participant 5 [NON])

- “development or developer type information, or communication just for the development staff” (Participant 6 [NON])

- “Manuals, technical terminology, resumes” (Participant 7 [NON])

- “Explaining a process … interpretation of information” (Participant 8 [NON])

- “Someone who is explaining things of a technical nature to folks who aren’t technical[ly] minded” (Participant 9 [NON])

- “The specifics of how something is going to happen, how to do a certain task, or how to deal with a certain product” (Participant 11 [NON])

- “A lot about detailed information for technologists, but not for the general business populace.” “Architecture documents.” “Project requirements.” (Participant 14 [NON])

These quotations reflect responses to question 7 in the semi-structured interviews: “When you hear the term ‘technical communication,’ what comes to mind?” (Note that the full list of questions can be found in Appendix A.) Clearly, much of the understanding within this sample population has to do with manuals, instructions, explanations of technical subject matter—and certainly technical communication is very strongly associated with those concepts. But nowhere do participants discuss “expanded” competencies such as visual design, project management, or knowledge management (one notable exception to this came in one response to the question about openness to hiring a technical communicator, where Participant 14 [NON] said that his company would like their communications specialist to take on project management and other roles). In one case, Participant 6 [NON] stated, “I’m not sure what a technical communicator would do, or what that role is responsible for.” Another, Participant 3 [NON], who had managed a team of communication specialists in the past, reported that she is “not familiar with the training of a technical writer” but that she (correctly) “suspect[s] that there is more to a technical writer than meets the eye.”

This pattern has considerable implications for TPC’s professionalization and legitimacy, at least within the study population. Whether the goal is formal professionalization, quasiprofessionalism, or contraprofessionalism (to use Carliner’s terms again), TPC needs a consistent, or “unified” vision, as Henning and Bemer called it, in order to achieve the kind of legitimacy that will make it viable and ensure that it is understood across disciplines. More research is needed to better measure that consistency.

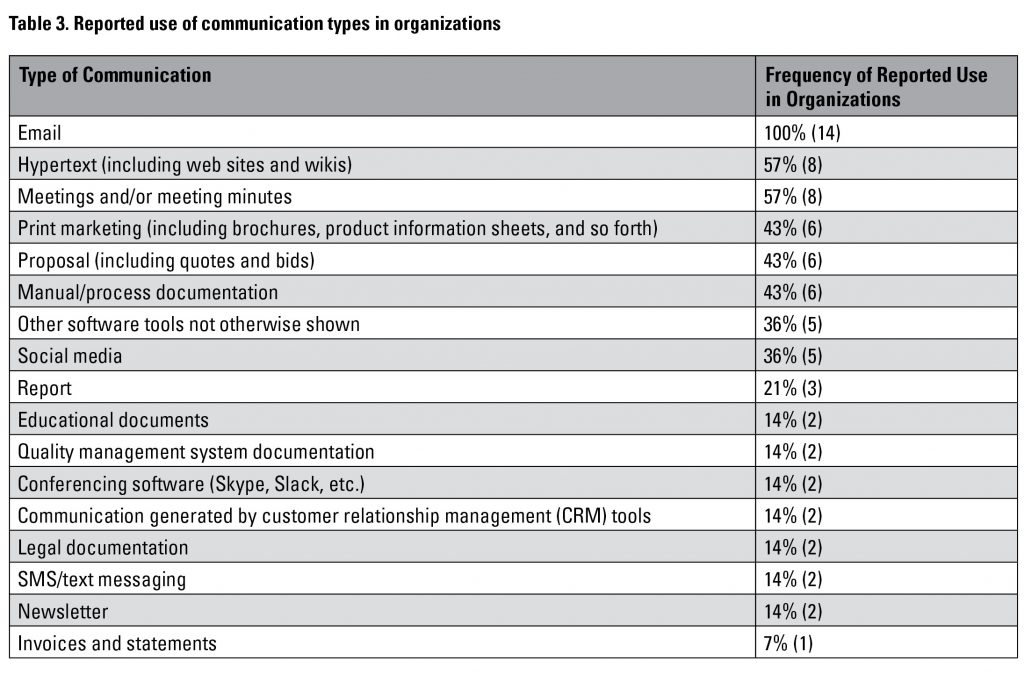

Pattern 3: Common communication types within organizations

The communication type that overwhelmingly emerged through the interview set was that of email. A full 100% (14/14) of participants mentioned it as being important in their organizations, and it was often the very first to be mentioned at all. Most of the time, it was discussed in the context of internal communication. Some participants, such as the high school teacher (Participant 11 [NON]), used it to communicate with external customers (namely, parents); at other organizations, it is often used for the purpose of sending job quotes and proposals, even if the participant is not directly involved in the process. Two of the practicing technical communicators in the study (Participants 4 [TPC] and 10 [TPC]) reported using email extensively; most of their reported interactions were with internal colleagues.

A few points are important to mention here. First, it is likely that not every participant is aware of, or mentioned, every communication type represented in their organization; therefore, these numbers are likely underrepresentative of certain communication types in organizations (it is difficult to imagine, for example, that social media are used by only 36% of the organizations in the study, a fact that likely reflects participants’ lack of exposure to that communication type in their organizations). Second, every participant did mention at least one—and, in a vast majority of cases, more than one—communication type that helps define goal-directed actions within each organization. Third, formal communication is taking place within all of the sampled organizations, and it is taking place a lot. Finally, we know that, in the study population, many formal communications are being created without the involvement of TPC professionals, raising the question of whether adding a technical communicator to those processes will result in formal communications that are produced more efficiently or that better address audience needs.

The important takeaway, though, is not simply that certain kinds of formal communications are taking place within the organizations in this study, but that these communications are (in a large number of cases in this particular sample) produced by non-TPC professionals. If this finding holds in a large number of organizations, there is arguably some untapped potential for expanded use of technical communicators (who are often markedly less expensive than subject matter experts, such as engineers, to the organizations that employ them). If the market for technical communicators will grow 11% between 2016 and 2026 as the Bureau of Labor Statistics suggests, how much would that percentage grow if managers, subject matter experts, HR professionals, and others in companies without TPC professionals on staff were more aware of the professional capacities of technical communicators? This is a question that must be considered as we continue to assess efforts toward professionalization and legitimacy of TPC.

Pattern 4: Reported effectiveness of organizational communication processes

Broadly speaking, 9 of the 14 participants (64%) reported their organizations’ communication processes to be effective or at least partly effective. There was some degree of nuance in nearly all responses; for example, Participant 11 [NON] stated the processes were effective “when used correctly.” Another stated that processes were generally effective; however, there were grammatical issues in many of the communications produced. Participant 4 [TPC] felt he did not have a proper frame of reference and was uncertain about the answer.

Three participants provided mixed responses: the engineer (Participant 2 [NON]) and director of security project management (Participant 14 [NON]) felt that their companies’ internal processes are at least somewhat ineffective but that external communications with clients are more effective, while the technical writer in higher education technology (Participant 12 [TPC]) reported that “[p]rofessional communication with external stakeholders is not formalized, but is probably more effective than our internal communications.” Finally, two participants reported ineffective communication processes in their organizations. Participant 9 [NON], a manager of project management software in her company, plainly stated:

Formal communications here are not good. We have to draft them if there is any significant unscheduled downtime for any of our clients. We just recently created a process for this but the process has not been working and it doesn’t follow what works best for us. We have too many people trying to manage something instead of picking someone to handle it. If we do pick someone to handle it, they aren’t around when we need them to communicate. Or they don’t listen to everything that happened and communicate the wrong thing.

Participant 1 [NON], the engineering director in the study, acknowledging that “communication is tough,” felt that improvements were needed in invoicing and forecasting, aligning communication objectives with corporate vision, and achieving transparency in both internal and customer communications.

Observation: Limited Openness to Hiring a Technical Communicator in the Foreseeable Future

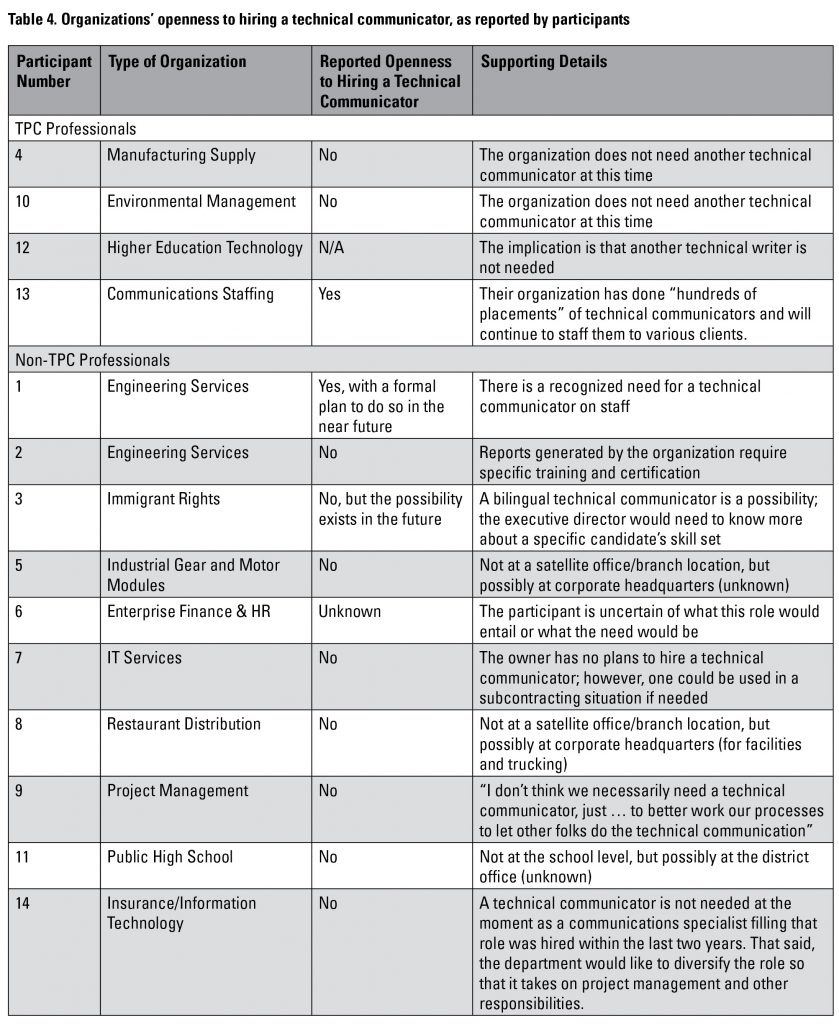

In determining an organization’s “openness” to hiring a technical communicator, I assessed the likelihood that an organization would actually consider hiring a technical communicator in the foreseeable future (a somewhat arbitrary term here, but for practical purposes, within six months). If the participant reported that their organization is or will be actively seeking a technical communicator for hire, I assessed the openness to hiring as affirmative. If the participant plainly reported that this was not likely to happen based on their knowledge, I assessed the openness as negative. This openness was not binary in many cases, and there were nuances in the responses.

Based on participants’ responses to the last question—“Do you feel management would be open to the idea of hiring a technical communicator?”—most of the organizations where they work did not plan to hire a technical communicator in the foreseeable future; this is true at ten of the organizations (71%), including the three organizations that already employ a technical communicator. Of the two definite affirmatives, Participant 1 [NON] reported that his organization (an engineering services company) would be actively seeking one in the very near future; Participant 13’s [TPC] company places technical communicators with client organizations on a regular basis. Participant 6 [NON] was unable to answer the question conclusively because of uncertainty on what the role would entail.

Two participants (Participants 3 [NON] and 7 [NON]) reported that their organizations would consider the possibility if the circumstances were fitting. Both participants are in positions of leadership: the executive director of a non-profit (where a bilingual technical writer could be useful in helping her with documentation and communication needs) and the owner of an IT services company (where technical communication services could be outsourced for print marketing and other needs).

The table below summarizes each organization’s openness to hiring a technical communicator as reported by study participants. Supporting details of each participant’s response are also provided.

Originally, I had considered this phenomenon a pattern among the pilot study’s findings, essentially like the four patterns discussed above. However, later feedback led me to realize that this phenomenon is different in a few key ways. First, organizations may not have a legitimate need to hire a technical communicator (or, put another way, a technical communicator may not add much value to an organization in its present form); in such cases, there may not be much more to say about it from a research perspective. In addition, the need derives from many factors—budgets, quantity of work, and so on—that are both difficult to control and difficult to generalize.

As I thought about the “openness to hiring” phenomenon, though, I realized that it can have an impact on the employment and use of technical communicators; and, at the very least, it merits discussion as a study observation. To that end, I will expand on factors that appeared to have an impact on whether a technical communicator would be hired in the organizations in question; these factors emerged from my analysis of study data thus far, and I intend to see how they bear out in interviews in further research.

Based on pilot study data, the lack of openness to hiring a technical communicator in these cases may derive, at least in part, from one of three factors. One is lack of knowledge of what a technical communicator actually does (or is capable of doing) among people making personnel decisions. Participant 6 [NON], a product manager, captured this idea well: “I’m not sure what a technical communicator would do, or what that role is responsible for.” Even Participant 3 [NON], a non-profit director who stated there would be some openness to the idea, stated, “I would need to know more about the skills of a [particular] technical writer before making the decision.”

Other participants focused on an implied exclusivity of writing skills or genre-oriented tasks of a technical communicator (as opposed to other, more diversified skills) as a basis for that lack of openness. Participant 2 [NON], an engineer, reported that “I don’t think my current company would be interested in hiring someone for the strict purpose of writing reports.” Participant 7 [NON], an IT services owner, reported no near-term plans to hire a technical communicator but said the possibility of subcontracting one existed when he needs trifolds or someone to focus on “the linguistics of it [marketing materials].”

A second factor is a perception that the competencies a technical communicator possesses (writing, editing, visual design, document control, and so on) can be duplicated by employees who are already on staff. This perception emerged specifically in three of the interviews in my study. Participant 9 [NON], a project coordinator, exemplified this well: “I don’t think we necessarily need a technical communicator, just need to better work our processes to let other folks do the technical communication.” Even one of the practicing technical communicators, Participant 10 [TPC], reported a limited perceived value of an additional technical communicator at his organization: “I believe the roles that a position like technical communicator would fulfill are adequately shared by many departments within the company [where] I work. The shared information and information dispersal responsibilities seem to be handled well by the group.” Though the participant did note that, with time and growth, openness to the idea of hiring a technical communicator may increase, this point underscores the importance of two themes: (1) potential challenges to pathways toward employment for technical communicators and (2) the importance of competency diversification and understanding of contextual fit within an organization.

One finding that emerged three times (and worth noting) was that organizations with a central office and one or more satellite offices may have different needs for a technical communicator. This finding was noted in interviews of the marketing coordinator at a large gear and module company (Participant 5 [NON]), the assistant manager at a large regional restaurant supply company (Participant 8 [NON]), and the teacher at a local school district (Participant 11 [NON]). Participants who worked at the satellite or branch office would say that their office did not have an immediate need for a technical communicator, but that it was possible that the central office may. For example, Participant 8 [NON] indicated that there would be no need for a technical communicator at the store level; however, the company’s facilities and trucking divisions (headquartered in a different state) may be able to use a technical communicator to write standard operating procedures for facility setups and instructions for their delivery drivers. This point implies that the technical communicator’s role in larger organizations may become more valuable at the organization’s headquarters, where corporate operations are overseen, large amounts of documentation are produced, and various kinds of communications are centralized and dispersed to satellite locations.

Notable Overlaps and Dichotomies in Data Across Findings Among All Participants and Within Sub-Groups

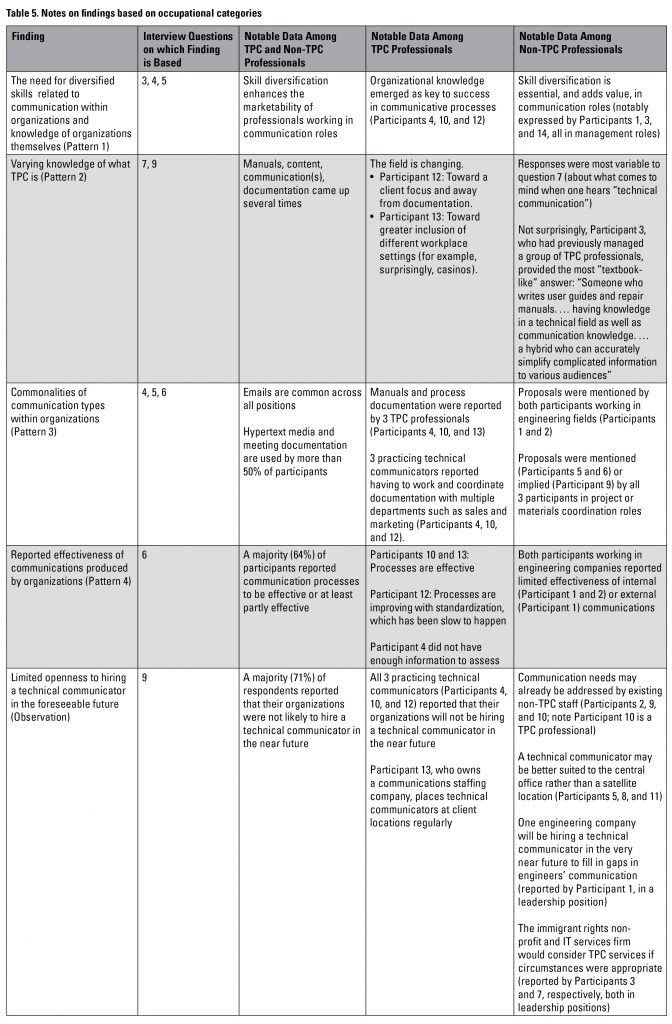

I noted some overlaps and differences in study data within different sub-groups and across different categories of findings. Many of these overlaps and differences were discussed in preceding sections. For ease of reading, I have organized notable similarities and differences in the findings among all participants, TPC professionals, and non-TPC professionals into the table below. In some cases, I observed more granular findings within industrial/occupational sub-groups (such as people working in engineering or management roles) and have noted those as well.

Implications

This study points to several notable implications that merit discussion and further research. First, interview data from participants suggest that TPC as a field continues to face challenges to its professionalization and legitimacy. Although these challenges cannot be generalized from a single pilot study, data suggest both the difficulty of positioning technical communication as a profession in organizations across a broad economic spectrum and the need to continue researching professionalization and legitimacy empirically. As the results of this research are formally communicated in the discipline’s journals, we need to ensure that the findings most pertinent to industry best practice continue to reach TPC professionals and that they, in turn, continue to communicate their needs to researchers.

Second, perceptions of TPC among non-TPC professionals reveal accurate conceptions of the field on a basic level; however, those conceptions lack the depth needed for an accurate understanding of the profession in a broader sense. Perceptions of the field’s functions ranged from communicating financial and business data to writing user documentation to “development or developer type information” to “explaining things of a technical nature.” In aggregate, participants’ responses suggested a kaleidoscope of perceptions with evidence of understanding fundamental aspects of TPC; however, nowhere did a participant mention visual design, knowledge management, or what some in industry might consider other “value-added” functions of TPC; and only once was project management mentioned as a specific competency.

On one level, this observation is understandable. People in one profession work with people in other professions without thinking much about what it is that their colleagues do. Why would a non-TPC professional care about, or need to care about, technical and professional communication? Furthermore, why would a technical communicator care about what non-TPC professionals think about the TPC field?

Both questions are important, and their answers derive from the fact that TPC, by its very nature, necessitates an inextricably collaborative dynamic among disciplines that is foundational to the success of a professional communication or project. Here, I again turn to the articulation view of communication that Slack, Miller, and Doak provided; in this process, the technical communicator becomes a part of the articulation and rearticulation of meaning co-constructed by various actors in communicative events. In this process, the technical communicator contributes a set of skills and sensitivities that optimally lead to clearer, more audience-centered communications yielding benefits for users, organizations, and stakeholders, including employees. Yet the process, and thus the benefits to end-user communications, are compromised when the technical communicator’s role and capacity are not fully understood by managers, subject matter experts, and others involved in creating, managing, and disseminating published communications. In some scenarios, decision-makers may leave the technical communicator out of the process completely; in others, they may decide not to hire (or may not think of hiring) a technical communicator, even when doing so would benefit an organization or project significantly.

The fact that the decisions of non-TPC professionals so often impact TPC professionals in profound and often existential ways speaks to the importance of how non-TPC professionals perceive and understand the field. In many organizations, particularly smaller ones, the person who manages any technical communicators on staff is a non-TPC professional with a background in engineering, sales, marketing, law, or some other discipline. There is a great deal of variability as to whether this person has extensive experience working with technical communicators, what kind of value the person places on TPC as a field, or whether the person has even had a class in professional writing. The same is true of those with whom the technical communicator must work on communication projects and even those who will be making decisions on whether to hire one. In the process of articulating meaning and finding a place of power in larger organizational and economic landscapes, the TPC professional must therefore consider the perceptions and backgrounds of non-TPC professionals involved in communicative dynamics.

A third implication that study data suggest is that obstacles exist to expanding the use of technical communicators in some workplace settings. In the study, these obstacles sometimes resulted from organizational size, whether the office is a company’s central or satellite location, the assumption of roles by non-TPC professionals, and a lack of understanding (by non-TPC professionals) of TPC as a profession and the value it brings. Questions need to continue to be asked, first, about how advocacy for the field of TPC can be promoted, as well as the contexts in which such advocacy should take place. In addition, questions should be asked about how non-TPC professionals develop an understanding of the field of TPC and how those in the field—both academics and practitioners—can help expand that understanding.

Findings also suggest that technical communicators need greater training in organizational matters. Among important considerations in this area are, potentially, how organizational politics function, how to navigate different organizational structures, how to assert their value in diverse workplace/organizational settings, and how to deal with unexpected contingencies that result from a lack of understanding of what they do. As teachers of TPC, we should ask such questions as: Can the acquisition of organizational knowledge be taught as a competency in TPC courses? If so, are we doing a good enough job teaching students about it? Even though organizational knowledge is often developed organically, there is something to be said about the importance of topics like organizational communication, organizational culture, and organizational psychology as part of a technical communicator’s professionalization.

Finally, there is an ongoing need to research the alignment of academic and practical perspectives on TPC. Conceptually, academics are interested in theory and pedagogy; practitioners particularly want to know about important competencies and how to make themselves continually marketable in a changing economy. Both benefit from and have a vested interested in research, and research is a significant piece of continuing to find common ground between theory and practice. As I indicated in the first implication on professionalization and legitimacy, academic research and industry practice must continue to inform one another; there must be a dialogue. Organizations like STC will continue to be instrumental in this dialogue.

Observed Limitations

As with any study, this research presents potential limitations that should be acknowledged. Over the course of my research so far, I have identified potential limitations in these areas.

Limitations of sampling method: As I discussed in the methods section, the qualitative sampling method I have used in the study is that of the snowball and convenience sample. This sampling method provides many benefits; however, one of the intrinsic limitations is that the base sample population is limited to people I previously knew or had previously encountered in some capacity. A truly random sample would be difficult to achieve in a study of this type; however, other sampling methods could be employed in future studies.

Limitations of participants’ organizational knowledge: An employee of an organization will have certain knowledge of that organization and its work processes—knowledge that varies as a result of what level in an organizational hierarchy the person occupies, what department they work in, what organizational artifacts the employee encounters through the course of their work, and where an employee works spatially and geographically.

Limitations of access: In the context of this research, I am referring to two kinds of access: my access to particular people and workplaces; and participants’ access to information, resources, and artifacts. If, for example, a study participant had broad access to an organization’s quality system, they are much more likely to know about the organization’s quality system documentation (standard operating procedures, work instructions, and so on). On the other hand, that same person may have nothing to do with customer-facing documents, such as project proposals, which substantially limits the data that I can get regarding the processes associated with customer-facing documentation in that organization.

Limitations of interview settings: Once I had recruited and obtained the proper written consent from study participants, the greatest challenge that remained was how to conduct the interview (where the brunt of the study data were collected). In this study, it is nearly impossible to standardize the interview format due to factors like geographical distance, scheduling, and the stated preferences of individual participants. As a result, the interview formats have varied from face-to-face to email-based to one phone interview (in the pilot study, none of the interviews was conducted using Skype or another synchronous meeting tool, although the study design does allow for that possibility). A face-to-face interview provides greater opportunity for conversational give-and-take that is more difficult to duplicate via email. On the other hand, email provides greater ease of documentation yet still provides an opportunity for follow-up. Though, as a researcher, I would prefer a more standardized format, I find that the format flexibility is beneficial to participants; of those who were interviewed, I did not have significant difficulty gathering data or following up when needed.

Limitations of design: The original study design did not include a request for artifacts such as marketing materials and proposal template text, and therefore no specific plans were included for an analysis of such artifacts. In discussion with a colleague, I recognized that having these artifacts could provide another important basis for analysis. This recognition leads to two possible adjustments to the study design, and they are not mutually exclusive: (1) asking participants in writing about obtaining written artifacts and (2) analyzing publicly accessible artifacts (such as Web content). Option 1 would require additional IRB review and written approval from participants and their organizations’ leadership. Option 2 would be both easier to implement and less likely to lead to conflicts with organizational leadership. Both would result in changes to the current study design.

CONCLUSION

Through my ongoing research, I seek to ask questions that will help us answer questions of significance to the legitimacy and professionalization of the field; in doing so, I hope to help TPC scholars think of questions that we have yet to ask in research on technical and professional communication practice—questions that academics will ask in large part to help the practical side of the field to grow its identity, marketability, and continued viability in industry settings.

When I first proposed this study, I was interested in learning about the types of formal communications that take place in organizations, how those communications were being created, and how technical communication was perceived by people working in different organizations. In many ways, those goals held steady from the beginning; however, they expanded to include notions of professionalization, legitimacy, and power because those constructs are inherent to the stability, viability, and marketability of technical communication as a field. Although I disagree with Pringle and Williams’s (2005) assertion that “[t]echnical communication has quite possibly arrived as a profession,” I believe that the field continues to professionalize and that our work as researchers will aid in that process. Through this professionalization will come greater legitimacy and power to articulate both linguistic and organizational meaning.

I see the contribution of this ongoing research as pragmatically combining academic theory with professional practice—not to seamlessly unify academic and industry views of technical writing, but to assert ways in which the two views can inform and learn from each other, exemplifying the productive affinity that St.Amant and Meloncon (2016b) suggest, identifying ways in which technical communicators can better professionalize and enhance their legitimacy in multiple disciplines, and building a more unified image of TPC and its value as perceived by people outside the discipline.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable input on the manuscript, as well as the following people for their encouragement and input on this project: Lee-Ann Kastman Breuch, Jason Tham, and Ruth Perrine Tudor Finke. Finally, the author acknowledges the Council for Programs in Technical and Scientific Communication (CPTSC) for related funding of subsequent phases of this research.

References

Adams, K. (1993). The history of professional writing instruction in American colleges. Dallas, TX: Southern Methodist University Press.

Albers, M. J. (2016). Improving research communication. Technical Communication, 63, 293–297.

Amidon, S., & Blythe, S. (2008). Wrestling with Proteus: Tales of communication managers in a changing economy. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 22, 5–37.

Baehr, C. (2015). Complexities in hybridization: Professional identities and relationships in technical communication. Technical Communication, 62, 104–117.

Blakeslee, A. M., & Spilka, R. (2004). The state of research in technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 13, 73–92.

Bloch, J. (2011). Glorified grammarian or versatile value adder? What internship reports reveal about the professionalization of technical communication. Technical Communication, 58, 307–327.

Blythe, S., Lauer, C., & Curran, P. (2014). Professional & technical communication in a Web 2.0 world: A report on a nationwide survey. Technical Communication Quarterly, 23, 265–287.

Carliner, S. (2001). Emerging skills in technical communication: The information designer’s place in a new career path for technical communicators. Technical Communication, 48, 156–175.

Carliner, S. (2012). The three approaches to professionalization in technical communication. Technical Communication, 59, 49–65.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Connors, R. J. (1982). The rise of technical writing instruction in America. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 12, 329–352.

Cushman, J. (2015). “Write Me a Better Story”: Writing stories as a diagnostic and repair practice for automotive technicians. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 45, 189–208.