By Daniel Ding

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Based on my examination of the websites of 42 elite Chinese universities, this article reveals relationships between Confucian notions of collectivism and deference to superiors and content features on the university websites.

Method: Using content analysis, I examined the following features on the homepages of the Chinese university websites three times in three consecutive months:

- political/national agendas,

- history and tradition,

- important people,

- groups of people; and

- campus views.

Results: My three examinations indicate that the Chinese university websites consistently show certain aspects of the above five features, which serve rhetorical and social purposes: political and national agenda claiming authorship of website content, history/tradition justifying current status, important people guiding university work, large groups of people showcasing the CPC ideologies, and campus buildings and structures symbolizing social elites.

Conclusion: Confucianism helps us discern patterns in the design of Chinese university websites. Despite its limitations, this study serves as a small window into the many relationships between Confucianism and Chinese university websites.

Keywords: Confucianism, Web design, culture, collectivism, content hierarchy

Practitioner’s Takeaway

When developing websites for their companies in China, website developers need to create a content hierarchy on the websites, giving priority to the content that features collectivism and deference to superiors, like presentations of “overall agendas,” authority endorsement, group themes, traditions, and buildings. More specifically, they should give attention to the following five suggestions:

- Present national agendas on the website, or carry news that features national leaders, to stress the company’s interest in some notion of common good for the entire nation.

- Publish political leaders’ talks or show their pictures, particularly pictures of leaders visiting the company.

- Make connections between a company’s traditions and its current status.

- Stress themes of collectivism, such as groups of employees, faculty, students, families, or consumers.

- Feature company buildings, walls, gates, gardens, or landscapes.

Introduction

In the past twenty years or so, a large number of researchers and practitioners have studied websites developed in China (Chinese websites), mainly as a business or a marketing tool; very few researchers have studied impacts of Confucianism, the single most influential philosophy in China (Ding, 2006; Yum, 1996) on Chinese websites. This article specifically addresses this gap in the literature on culture and the Web by studying Chinese university websites. It is significant to study how Confucianism influences Chinese university websites, specifically for three major reasons.

First, communication between East and West “can be the most problematic” because of the extreme cultural differences between them (Barnum, 2011, p. 132). Chinese culture, particularly Confucianism, is very influential in the East (Ding, 2006; Fung, 1997; Yum, 1996), so studying how Confucianism influences Chinese websites helps to narrow the gap between the East and West in online communication expectations.

Second, China is the second largest economy in the world, and its economy is still developing at a rapid speed. China’s rapid development of economy has enabled China to expand the potential of its universities. Now it boasts the largest university student population in the world (Farnsworth, 2005; Gardner & Whitherell, 2007; Tang 2011). Globally, 20% of the world’s international students come from China (Choudaha & Chang, 2012). In the USA, Chinese students account for more than 31% of all international student enrolments in recent years (John, 2016; Zong & Batalova, 2016). On the other hand, China is hosting more and more international students. In 2016, for example, more than 440,000 international university students were enrolled in China, a 35% increase from 2012 (CSIS, 2018). In other words, more and more international exchanges are occurring between China and the rest of the world, especially the Western world. Online activities play an important role in these exchanges. Online communication is thus a major bridge between Chinese universities and other universities in the world. Therefore, the bridge builders—technical communicators—need, among other things, to understand the cultural expectations that underlie presentations of information on Chinese university websites.

Third, as one factor that influences Chinese university websites, Confucianism could be missed or misinterpreted by technical communicators, especially those from non-Confucian cultures. Thus, this article, through a content analysis of various visual and verbal information on Chinese university websites, reveals and interprets the connection between Confucianism and the content on the Chinese university websites.

To be more specific, I argue that the Confucian concept of human kindness (Ren) influences the content features on Chinese university websites and that these features serve various rhetorical and social purposes to represent the universities. I first review relevant literature on cultures and website design. Second, I introduce the Confucian concept of human kindness (Ren) as the major philosophical perspective that shapes the communication process in China. Third, I describe my research method and procedures. Next, I report the research results. Then, I analyze the significance of the results—the functions of the Web content features. Finally, I suggest some implications of my research findings for technical commination practitioners.

I want to be very clear about what I claim and what I do not claim in this article. Arguing for the impact of Confucianism in the creation of Chinese university websites does not suggest that Confucianism is the only factor that impacts the content on the Chinese university websites. Web design is influenced by many factors, such as general cultural values, marketing strategies, social considerations, legal issues, Web design theories, audience information needs, and practical measures. Thus, it would oversimplify the issue of Web design to imagine that the Chinese university websites are influenced by Confucianism only. However, as I will show, Confucianism does contribute to the design of the Chinese university websites, and, therefore, studying these websites from the angle of Confucianism will help to reveal patterns that audiences would not be able to see in the design of these Chinese university websites if we approach them from other angles.

Literature Review: Ways Cultures Shape Web Design

Scholarship in computer science, marketing business, sociology, communication, cultural studies, and Web design technology has already established that cultures affect presentations of information on the Web. Basically, there are two corpora: studies focusing on websites designed in countries other than China (non-Chinese websites) and studies focusing on Chinese websites. Studies from both corpora inform this article.

Studies on Non-Chinese Websites

Although many previous studies analyze website designs as driven by cultural values, content analysis seems to be a major research method in studies of Web content. For example, to either confirm or reject Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions, Callahan (2007) analyzes 900 university websites from 45 countries by comparing and contrasting people, buildings, animation, navigation styles, page length, and other design features on these websites. Similarly, Marcus and Gould (2012) introduce Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions by applying them to websites from various countries to demonstrate the cultural values indexed by the five dimensions. What is noteworthy is that they have identified and tested the features to look for on the Web that index each of the five cultural dimensions. For example, a highly collectivist culture may show group activities, official slogans, political agendas, government officials, or political leaders on the Web. Their study was first published in 2000, and, since then, it has been invoked or cited 1,067 times (Google, 2018), which suggests that it is very influential in the field. Singh’s (2003) study of websites from Germany, France, and the USA proposes a framework for studying website content in manifesting various cultural values. The study suggests that collectivist cultures and cultures that respect power may publish national policies and slogans, feature important people and groups, stress patriotism and history, and carry images of buildings. In this respect, Singh would agree with Marcus and Gould. St.Amant (2005) defines a strategy for analyzing and designing websites for users from various cultures. In his study, St.Amant points out that university websites can be used as the websites for prototype analysis because such sites employ features that are “accepted by a broad audience within a particular cultural group” (p. 82). This point is closely related to this current study because it suggests that within a particular culture, university websites well represent the cultural features.

The review of the above studies suggests that first, content analysis reveals that design of websites is shaped by local cultures. Second, some of the website content features are attributable to cultural dimensions of collectivism and deference to power.

Studies on Chinese Websites

Studies in this group are more closely related to this article. Again, content analysis appears to be the major research method in this group. Ding’s (2010) article, for example, compares the Chinese Foreign Ministry’s (CFM) website with the U.S. State Department’s website and shows that the CFM website tends to use numerical lists without using action-oriented verbs when providing instructions. Ding attributes this feature to the influence of Confucianism and another traditional Chinese cultural value of naming the unknown world with nouns. Ding’s is one of the very few studies that applies Confucianism to analysis of Chinese websites, though it analyzes navigation styles only. Hawes (2008) examines 119 Chinese corporations’ websites to see how the concept of “corporate culture” is represented on the websites of large Chinese corporations. Their analysis suggests that information representing cultural values “appear[s] to be a mixture of traditional Confucian principles … and socialist principles” (p. 57). Particularly telling is the author’s finding that these websites “take pains to publicize their support of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and its policies” (p. 53) and “display their Party credentials as a major aspect of their ‘corporate cultures’” (p. 54). This finding supports Marcus and Gould’s (2012) observation that a highly collectivist culture may display political agendas on its websites.

Hillier (2003) studies some Chinese websites that use both Chinese and English, and claims that cultural context determines usability of bilingual or multilingual websites. Therefore, Hillier suggest that bilingual or multilingual website developers should consider both cultural and usability factors. Couched in Gould and Marcus’s (2012) theories, Hillier (2003) believes that content features on websites manifest “Hofstede’s cultural clusters” (p. 10). Hillier’s study suggests that content features identified by Gould and Marcus on websites correspond to associated cultural values. Qiu et al. (2004) focus on technical aspects of the top 100 Chinese universities by analyzing the “links” between websites, between Web pages, or between websites and Web pages. Though the authors do not employ Chinese culture in their study, they do point out that Web Impact Factors do not work for Chinese universities because their websites do not contain much “academic information” (p. 471) and that a Chinese university’s higher social status may attract more links to its website.

Tang (2011) analyzes ways pictures from the websites of 100 Chinese universities and 100 U.S. universities are used as marketing tools to attract potential students. Couched in Hofstede’s, Hall’s, and other cultural or marketing theories, Tang’s study shows that Chinese university websites, as a marketing strategy, display school administrators much more frequently than the US university websites. This finding supports Hofstede et al.’s (2010) and Marcus and Gould’s (2012) observations that high power-distance countries such as China show deference to authorities. Wurtz (2005), in her study, applies Hall’s and Hofstede’s cultural theories when analyzing the McDonald’s website from China and compares it with corresponding websites from some Western countries. The results show a great contrast between the websites from the high-context cultures and those from the low-context cultures, and thus indicate that the websites designed in collectivist cultural environments stress collectivist cultural values such as relationships and groups.

The review of the studies on Chinese websites, though limited in number, demonstrates that various Chinese cultural values shape the websites, but none of these studies analyze the websites consistently from the angle of Confucianism as an influencing factor. The above review suggests that we still know very little about how Confucianism contributes to the content features on Chinese websites or how these features function on the websites. To address these issues, I need first to introduce Confucianism in the next section.

Confucian Notions of Deference to Superiors and Collectivism

Because this article studies how Confucianism impacts the content on the Chinese university websites, this section introduces Confucianism, especially its concept of human kindness (Ren).

Researchers have already pointed out that Confucianism heavily influences communication process in the Chinese tradition (Huang et al., 1994; Yum, 1998; Ding, 2005; Abubaker, 2008). I’d like to stress that the two core values of Confucianism—proper human relations and modesty—affect the communication process in Chinese culture more than any other values of Confucianism.

In Confucianism, three basic ethical principles regulate social interactions, including communication:

- Ren (human-heartedness, to love others)

- Yi (to be righteous)

- Li (proper conduct)

These three principles guide all human behaviors in society (Chen, 1997) because they define “a traditional concept, that of chun-tzu or [morally] superior man” (Chan, 1998, p. 15) by providing standards for becoming a superior person (Herr, 2003). Simply put, the three principles enable us to differentiate a morally acceptable behavior from an unacceptable one.

Fung (1997) elaborates on the interrelatedness of these three principles: Ren is made manifest in Yi and Li. Yi means “ought-ness” of a situation (p. 42), meaning that to be righteous, people ought to fulfill certain duties in society. The primary duty is to love others, or Ren. But how do they show this “love”? For Confucius, they must follow Li, (proper conduct), “the written code of honor governing the conduct of aristocrats”—morally superior humans (Fung, 1997, p. 155). Li consists of several values that Confucianism holds up as moral standards, of which proper human relationships and modesty are most closely related to communication process.

Proper Human Relationships

Confucianism considers proper human relationships as the basis of a harmonious society. Confucius (1991) identifies five dual relationships: monarch-subject, father-son, husband-wife, elder-younger, and friend-friend (p. 31). Of these five dual relationships, family relationships are the basis of all relationships because the family is the basic unit of human community. For Confucius, therefore, the monarch-subject relationship is the extension of father-son relationship, so Fung (1997) points out that the dual relationship between monarch and subject “can be conceived in terms of that between father and son” (p. 21). The father-son relationship is the core of the five dual relationships, just as Yao (2001) argues that Confucius put the father-son relationship “above all other considerations” and family responsibilities above all other duties (p. 181). The family responsibilities entail that sons must love fathers, wives must obey husbands, and the younger must respect the elder. By extension, subjects must love, obey, and respect the monarch. Mencius (1991), who transmitted and developed the teachings of Confucius and who was second only to Confucius himself in creating the historical importance of Confucianism, claims that “if everyone loved his parents and treated his elders with deference, the whole world would be at peace” (pp. 122–123).

In the Confucian philosophical system, the monarch, the father, the husband, and the elder are superior to the subjects, the son, the wife, and the younger. These distinctions are further developed by Dong Zhongshu, a major Confucian philosopher in the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). When expanding on Confucius’s moral philosophy, Dong Zhongshu proposes that, in each dual relationship, the superior guides the inferior (He et al., 1982; Chan, 1998; Huang et al., 1994). In other words, the superiors have “become the standards for the inferiors to observe” (Chan, 1998, p. 277). So the inferiors must treat their superiors with deference, and only in this way can family or social harmony be maintained. When conflict occurs in the family or chaos occurs in society, the blame is always put on the inferior members because the inferiors must have behaved inappropriately towards the superiors; thus, the only way to resolve the conflict or to bring order out of chaos is for the inferiors to become humble, blame themselves, and show deference to the superiors (Yao, 2001).

Influenced by Confucianism, Chinese culture highly respects superiors and power. In the communication process, establishing proper human relationships requires communicators to pay deference to their superiors and power.

Modesty

Modesty, according to Confucianism, is another moral virtue that individuals must uphold. Confucius (1991) observes that “the morally superior has morality as his basic stuff and … by being modest gives it expression” (p. 157). Individuals display modesty by de-emphasizing the self and showing deference to others in social interactions. From Confucius’s perspective, individuals exist only through their relationships with others: Wherever they are, individuals must have a name defined by the relationship structure—monarch, subject, parent, son, wife, friend, etc. Individuals do not exist without assuming a name that designates their positions in the relationship structure (see also Yee, 2001, p. 71), because they believe that self-actualization occurs only in social relations. In Herr’s (2003) words, they exist in a “net of five human relations” (p. 471). This emphasis on relationships leads people in Chinese culture to deemphasize the self and to stress the collective (Huang et al., 1994; Winfield et al., 2000).

Driven by Confucianism, Chinese culture is highly collectivistic. In Chinese professional and technical communication, communicators usually deemphasize themselves by describing themselves in derogatory terms and describing others in laudatory terms while emphasizing the common interests of the collectives or of all parties involved, or they may stress the importance of long-term cordial relationships rather than their own business profits (Huang et al., 1994). Modesty requires communicators to pay respect to the collectives in the communicator process, in order to establish their own credibility.

Methodology

Formulating Research Questions

As the review of literature shows, researchers and practitioners provide strong evidence that content analysis reveals that cultural dimensions of power distance and individualism/collectivism are applicable to analyzing website content and that culture influences Chinese website design. However, none of the studies of Chinese websites is couched in Confucianism as an overarching influencing factor. Most of the studies look at the websites in the context of marketing/business, so we still know very little about how Confucianism contributes to the content features on Chinese websites or how these features function. If, as Steenkamp and Jan-Benedict (2001) have pointed out, websites used in different contexts, such as business vs. academics, manifest cultural values differently, certainly we have yet to lean how Chinese university websites manifest Confucianism. This article extends beyond the previous studies by examining how Confucian notions of collectivism and deference to power impact Chinese university website design. To do this, this article answers these two questions:

- How do the content features, both verbal and visual, on the Chinese university websites manifest Confucian notions of collectivism and deference to power?

- What rhetorical and social functions do the content features perform to represent the universities?

In answering the first question, we identify the surface content features as influenced by Confucian notions of collectivism and deference to power. But to gain a deeper understanding of the Web content, we need to go beyond just identifying the surface features. That is, we must also find out how they serve to virtually represent the universities in society, so we must also examine their functions. Researchers suggest that Web content features perform their various website functions to represent the Web owners (Herring et al., 2007; Liao et al., 2006), so the second research question has been formulated.

Research Method

To address the research questions, this article employs content analysis of various visual and verbal information on Chinese university websites, discussing how Confucianism influences the content information on the Chinese university websites. Content analysis is a very common method of investigation for studying websites (Babbie, 2015; Baek & Yu, 2009; Liao et al., 2006). Scholars indicate that content analysis of information on websites helps measure cultural impact on website content (Calabrese et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2005; Tang 2011; Wang & Cooper-Chen, 2009), and researchers have used content analysis to analyze verbal and visual representations on university websites (Hartley & Morphew, 2008; Saichaie & Morphew, 2014). They also use content analysis to analyze the purposes, functions, and themes of the content (Herring et al., 2007; Lawson-Borders & Kirk, 2005; Saichaie & Morphew, 2014; Trammell & Keshelashvili, 2005). Therefore, a content analysis of both verbal and visual information on Chinese university websites was conducted.

Data to Be Collected: Content Features for Analysis

To address the research questions, I need to identify the web content features that manifest Confucian notions of collectivism and deference to superiors. In this respect, scholarship has presented a wide variety of perspectives on culture and content features. For example, Hawes (2008), Marcus (2003), and Marcus and Gould (2012) suggest that collectivist cultures tend to show political/national agendas/announcements on their websites. Marcus and Gould (2012), Singh (2003), Singh and Matsuo (2004), and Singh et al. (2003, 2005) indicate that cultures that value deference to superiors tend to emphasize tradition/history on their websites. Marcus and Gould (2012), Paek (2005), and Singh and Martinengo (2015) discover that cultures that show deference to superiors focus more on illustrating important people, authorities, or government officials on websites. Marcus (2003), Singh and Matsuo (2004), Tang (2011), and Wurtz (2005) show that collectivist cultures often use images of groups on their websites. Dormann and Chisalita (2002), Marcus and Gould (2012), Okazaki and Alonso Rivas (2002), and Tang (2011) correlate portrayal of buildings, structures, and natural scenes on websites with cultures that value collectivism and stress deference to superiors. Singh’s (2003) framework for studying content features in depiction of cultural values on websites “has been empirically validated and shows adequate reliability” (Singh et al., 2005). Baack and Singh’s (2007) study of 274 websites from 15 countries in Asia, Europe, and North America seems to confirm the various correlations between cultures and website content the above cited scholars study. Informed by the above studies, this article chose the following five categories of Web content features for analysis:

- Political/National Agendas,

- History/Tradition,

- Important People,

- Groups of People, and

- Campus Views.

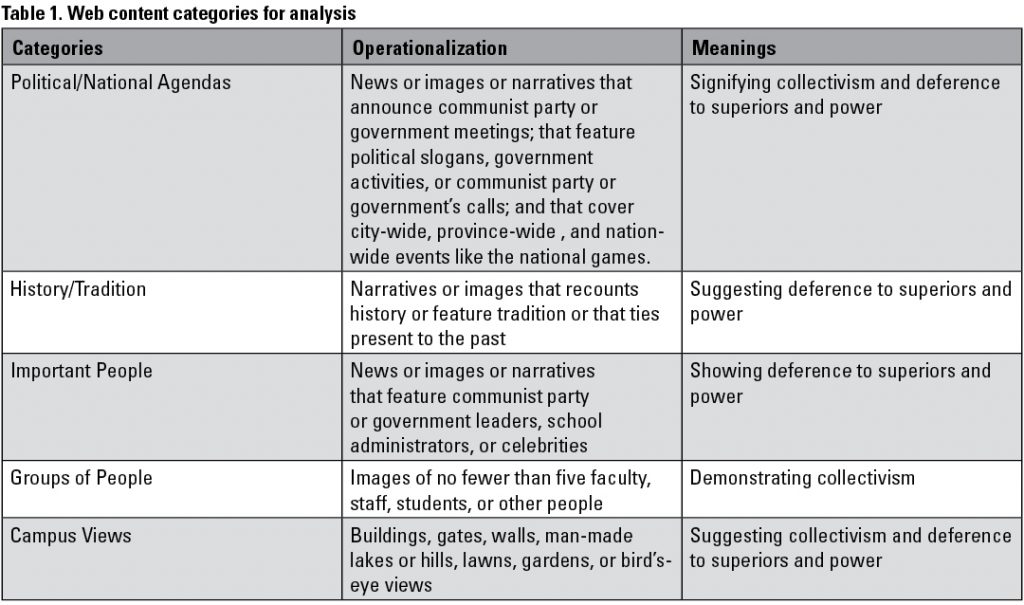

Based on these five features, I developed a rubric for collecting data from the websites. The rubric explicitly provided criteria to classify the content features and guided analysis. Table 1 shows the rubric—the content features for analysis, their operationalization, and their meanings.

Collecting Needed Data

Content analysis allowed me to collect the data I needed to address the research questions, because it is an empirically validated research method for studying both visual and verbal information “to identify the messages and meanings directly and through inference” (Saichaie & Morphew, 2014, p. 506; see also Krippendorff, 2004). Generally speaking, content analysis allows us to classify visual and verbal messages, analyze each of theme, assign each a category we have designed for the study, and designate a cultural value the category manifests, as evidenced in Simon’s (2001) and Baack and Singh’s (2007) studies. University websites are vehicles of communication that employ both visual and verbal messages, so content analysis enables us to classify and examine the university website content features. It enables us to establish crucial links between cultural dimensions and Web content features as driven by various cultural dimensions.In this particular study, content analysis allowed me to analyze all the verbal and visual messages and to classify them into one of the five categories, guided by the rubric as shown in Table 1. To be more specific, featuring political/national agendas and important people on websites demonstrates the website owners’ desire to pay respect to superiors and power. Showing history/tradition helps justify and reinforce the current status of superiors and power. Using groups of people suggests website owners’ endorsement of collectivism. Structures and buildings are symbols of power and represent collectivist achievements (Lasswell, 2017; Samuels & Samuels, 1989; Williams, 1996). In short, these five features give expression to the perspectives of power and collectivism.

Choosing Chinese Universities

Choosing Chinese Universities

I chose the websites of the 42 Double First-class (shuangyiliu) Chinese universities. In 2005, the Chinese government initiated the “Double First-class University Plan” and implemented it in 2007 in an effort to create world-class universities and disciplines by 2050 (Charlesworth Group, 2017). The Plan lists 42 Chinese universities, which are already elite universities in China and therefore are highly influential. According to a Chinese government spokesperson, these universities were selected through “a process of peer competition, expert review, and government evaluation” (ICEF, 2017). Because these 42 universities represent top-level education of China’s institutions of higher education, they represent China’s higher education in a more general sense.

Choosing University Websites

I examined only the homepage of a university’s website because a homepage represents “the face” of the university and serves as the official gateway to the other pages on the website (Askehave & Nielsen, 2005; Baek & Yu, 2009; Wang & Cooper-Chen, 2009; Tang, 2011; Zhang & O’Halloran, 2013). A homepage defines how a website is structured and information is organized (Bateman, 2008). Thus, I believe the homepage of a website is most directly and extensively affected by its native culture. In addition, studying a university’s entire website is beyond the scope of this paper.

Procedures

I scrutinized every homepage, counting both visual and verbal representations on the homepage. I also clicked buttons if and only if they suggested a category I was looking for, like “university history” and “students’ ideology work” because I wanted to find out the details of the content. I did not click any non-homepage buttons.

I browsed all the homepages of the 42 Chinese universities’ websites one by one on February 27, 2018. When I came to one homepage, I examined all the items on the page, including the lead image, images that accompany news, news items, narratives, announcements, and all the buttons. I analyzed each item and assigned it to one of the five content categories. If an item matched the feature I was looking for, I wrote down “1” under that feature. For example, under “campus views,” I wrote “1.” The number “1” means that one university’s homepage features “campus buildings, gates, walls, trees, hills, lakes, or lawns.” If news on a homepage reported a government officials’ activities, it counted as “1” under “important people.” If a large group also appeared, e.g., listening to the government official, then it also counted as “1” under “groups of people.” I want to emphasize that I focus on how many homepages display a particular feature, not how many times a particular feature appears on a university homepage. “One-time appearance” of a particular feature on a homepage is evidence, as significant as “two-time or three-time appearance” suggests the impact of culture. Finally, a picture featuring a group of people with structures as the background, such as a university gate, is recorded as both “groups of people” and “campus views.”

Because some universities update their websites every day or every week, to guarantee reliability of the results, I repeated the above procedure twice—one month and two months after my initial examination of the 42 universities’ websites.

Results

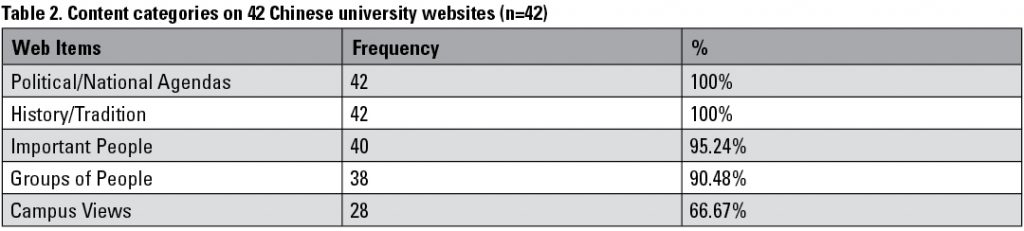

This article argues that Confucian notions of collectivism and deference to superiors impact content on Chinese university websites. Indeed, of all the 42 homepages, 42 promote “national and political agendas”; 42 feature “history/tradition”; 40 depict “important people”; 38 portray “groups of people”; and 28 display “campus views,” including buildings, university walls, gates, or landscapes.” Table 2 summarizes all these numbers.

Political/National Agendas

Fort-two (42) university websites carry items that promote “national and political agendas,” as Table 2 shows. This category of content features signifies “collectivism and deference to superiors and power,” as Table 1 indicates. This is perhaps the most prominent feature on the homepages of the university websites so that when our eyes scan a page, we constantly encounter words or phrases like “Proudly stride into the new era (a phrase coined by Xi Jinping, referring to the years under his rule), “the Party,” “Xi Jinping,” “political tasks,” “the Party’s original aspirations,” “Study the proceedings of the Party’s Congress,” and “study the series of speeches by Xi Jinping.” Pictures of political leaders presiding over CPC meetings are often used as the background of political slogans.Political/national agendas appear in several formats. First, they may appear as lead images. Second, they may appear in news reported on the homepages, often with accompanying pictures. Third, they may appear in the column of announcements on the homepages. More often, they appear as clickable images placed either towards the bottom of the homepages or on the side. They feature Xi Jinping’s profile picture, the emblem of the CPC, the site of the CPC Congress, or a picture of Xi Jinping addressing the Congress. All the 42 universities have these images on the homepages of their websites.

History and Tradition

Forty-two (42) university websites contain the feature of “history and tradition,” which suggests “deference to superiors and power,” as Table 1 indicates. Most of the universities show their histories and traditions by employing clickable buttons on top of the homepages. These buttons are labeled variously “General Survey,” “Overview,” “History,” or “University Tradition.” Some universities employ clickable images that display some photographs from the past or the exhibition hall of the university’s history. A click on one of the buttons embedded within the image will take you to a page that features extensive discussions of the university’s history and tradition.

This feature often registers accounts of particular individuals significant in the history of the university, such as famous graduates, political figures, or social dignitaries. For example, Qinghua University lists Xi Jinping and Hu Jintao; Beijing University boasts Mao and Hu Shi.

Important People

Forty (40) university websites contain the feature of “important people.” This feature suggests “deference to superiors and power,” as seen from Table 1. The types of important people who appear on the university websites are government officials and/or school administrators. They are always depicted as authoritative figures giving instructions or as caring leaders visiting faculty, staff, or students or touring campus. For example, Ocean University of China’s homepage devotes its lead image to Vice Premier Liu Yandong, who, among a large of group of school administrators and faculties, is talking to a man. The caption claims that Politburo Member and Vice Premier Liu is issuing directives. Similarly, Beijing University’s homepage devotes its lead image to a large but crowded hall where school administrators are sitting at a large table in the middle among a huge crowd to celebrate the Chinese New Year of 2018. Tsinghua University’s homepage features a picture of school administrators visiting faculties on the Chinese New Year’s Day.

Groups of People

Thirty-eight (38) university websites depict “groups of people,” a feature that demonstrates “collectivism,” as shown by Table 1. These websites feature two types of groups. First, groups of faculty, staff, or students collectively bring honor to campus; second, groups of faculty, staff, or students attend political meetings. For example, Zhengzhou University’s homepage features four rows of students singing on the stage of a vocal competition. More often, the homepages publish pictures of large meeting halls with huge crowds of participants. For example, Minzu University of China’s homepage carries a picture of a large group attending a CPC meeting on campus. East China Normal University’s homepage shows a picture of 15 school administrators posing for pictures at the site of the Shanghai Municipal Congress of the CPC. Yunnan University devotes the lead image on its homepage to its campus-wide faculty meeting.

Campus Views

Twenty-eight (28) university websites show “campus views,” a Web feature that suggests “collectivism and deference to superiors and power,” as Table 1 indicates. The homepages of the 42 universities’ websites often depict large structures on campus, including a bird’s eye view of campus, groups of buildings, single buildings, and campus gates with walls. For example, the homepage of Renmin University of China carries a large picture of a tall building with a wall extended to its right surrounded with bamboo groves. Northwestern Polytechnic University carries serval pictures of buildings with decorated walls on its homepage. The lead image of Zhongshan University’s homepage features two walls with a building in between; Shandong University and Huazhong University of Science and Technology devote their homepages to pictures of campus gates with walls extended to either side.

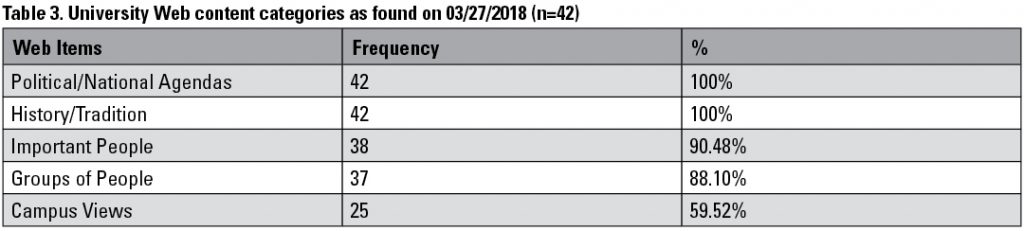

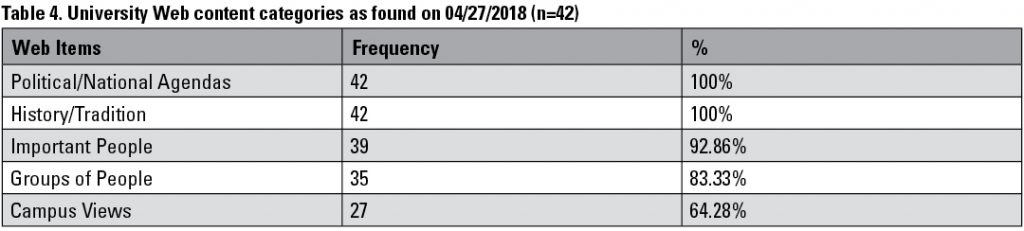

My Second and Third Examinations

To guarantee reliability of the data, I examined the homepages of the 42 universities’ websites two more times, on March 27 and April 27, because some universities update their homepages every day or every week. The results of my second and third examinations are consistent with the results of my initial examination. Tables 2 and 3 illustrate the results of my second and third examinations.

As you can see from these two tables, rates of the first two categories remain the same, which suggests that these two are essential to a Chinese university website. In other words, the website seems compelled to demonstrate the prominence of these categories by presenting them constantly on the Web. The rates of the other three features changed very slightly, but the changes do not alter consistency of the results throughout my three examinations of the websites. So the results of my examinations of the homepages of the 42 Chinese universities’ websites suggest that these universities may update the content but not the content categories. My findings suggest that these universities’ websites value collectivist interests and show deference to superiors, two cultural values motivated by Confucianism. To understand how the five content categories function, I will analyze their functions in the next section.

Discussion

In this article, I argue that Confucian notions of collectivism and deference to superiors contribute to the content features on Chinese university websites and that these features serve various rhetorical and social purposes to represent the universities. The previous section shows that the Chinese university websites contain various aspects of the five content features that manifest these two Confucian notions. In this section, I discuss the rhetorical and social functions of the five content features on the websites.

Political/National Agendas

No other features manifest the Confucian notions of collectivism and deference to superiors more prominently than this feature. It appears to be the overarching theme that frames the entire homepage, as all the 42 university websites analyzed display this feature on their homepages. Often, this feature takes up the entire homepages, as demonstrated by Xian Jiaotong University, Rennin University, Yunnan University homepages, just to name a few. Thus, these homepages look more like portals to governments’ websites.

The heavily politicized feature on the homepages translates into authorship. In other words, this feature fulfils the rhetorical function of authorship. In the Chinese tradition, authors did not create texts; instead, “texts created their authors” (Denecke, 2017, p. 344). For example, traditionally, Confucius has been considered the author of The Analects simply because it carries his teachings and invocations though the text was composed by his disciples after his death. The attribution of authorship to authoritative figures helps enhance the significance of the text and facilitate its authoritativeness, as in the case of The Analects. The impact of this particular way of generating authorship stretched well beyond early Chinese dynastic periods, going on to shape our views of authorship even in present-day China.

The heavily politicized feature on the homepages translates into authorship. In other words, this feature fulfils the rhetorical function of authorship. In the Chinese tradition, authors did not create texts; instead, “texts created their authors” (Denecke, 2017, p. 344). For example, traditionally, Confucius has been considered the author of The Analects simply because it carries his teachings and invocations though the text was composed by his disciples after his death. The attribution of authorship to authoritative figures helps enhance the significance of the text and facilitate its authoritativeness, as in the case of The Analects. The impact of this particular way of generating authorship stretched well beyond early Chinese dynastic periods, going on to shape our views of authorship even in present-day China.

The strong authorial presence in the Web text through recurring images and names of the political leaders with their official titles as seen, for example, on Lanzhou University’s homepage, the CPC agenda as evidenced on, for example, Xinjiang University’s homepage, and political slogans as displayed on, for instance, East China Normal University’s homepage, outright call for a paradigmatic author figure. This author figure serves as a political, moral, ideological, administrative, pedagogical, and perhaps even academic authority in the Web text, just as Confucius serves as the ideological, pedagogical, and moral model in The Analects.

At a more societal level, this authorial presence then serves the purpose of building an ideologically unified social structure. This presence ensures that only one voice is upheld—the voice of the Party and the government. Chinese culture prefers monism instead of pluralism; especially in creating and transmitting values, beliefs, and ideas; particularly those of the ruling class (Zhang, 1991). The author figure on the websites serves to strengthen administrative power and official ideology and to coordinate with the national agenda that ideological and political work must be stressed in pedagogy and in the entire curriculum (Xi, 2016). Looked at in this way, the authorial presence on the university websites serves as pedagogical as well as ideological authority. It is just one online mechanism for the CPC to maintain its domination over college education and curriculum. It represents the CPC’s attempt to spread its ideology as the sole legitimate ideology, to unify values, beliefs, and ideas, and to manipulate the consciousness of college instructors and students. As Lu (2017) forcibly argues, many of the CPC’s rhetorical strategies to govern the nation are “rooted in Confucian tradition” (p. 20).

History/Tradition

Chinese culture always stresses the roles of history and tradition in society. In Chinese antiquity, Confucius (551–479 BCE) invoked history and tradition of the Xia dynasty (ca. 2070–ca.1600 BCE) and the Shang dynasty (ca. 1600–ca.1046 BCE) as model societies. Confucius highly praised Zhou because it was devoted to these past two dynasties by emulating their splendid civilization. Confucius himself loved history and tradition, so he called for “applying the past rituals” to his own society (Confucius, 1991, p. 125). Here, Confucius saw civilization as cultural growth, born in the past but stretched through time to his own society. More important, he argued that individuals should apply past knowledge to their contemporary situations, as Ames (1983) points out.

This tradition of flirting with the past continues to impact the present-day Chinese society, as suggested by all 42 university websites that showcase their histories and traditions. These universities often appeal to the past to show their “thick and heavy” (hou zhong, meaning rich and extended) historical traditions, as, for example, Beijing University, Xian Jiaotong University, and Sun Yat-sun University websites show. Rhetorically, the historical narratives serve to show the universities’ political and academic muscle. Extended years of ideological and academic tradition is a guarantee that a university will set a new record both ideologically and academically. Like Confucius who looked to the past for inspirations to support his philosophy of “applying the Zhou rituals,” here, Chinese universities draw inspirations from the past to showcase their current ideological excellence and academic excellence.

The historical narratives convey traditional values, but they also have values for the present tasks and constitute the foundation for the present as well. These universities recognize their historical traditions as a new starting point to build themselves into world-class universities. Like Confucius who applied historical knowledge to his contemporary circumstances, they also carry historical traditions one step further in applying them to the present situations. It seems that learning various traditions from the past is essential to elite education, which is thus infused with values attributed to history and tradition. However, the “History” or “Tradition” of a university does not just narrate the past as a series of events but stresses it as a series of actions taken by the university. In other words, the university searches for the past to reinvigorate the present; the university uses the past as a means to bolster the present, in the way urged by Confucius.

Important People

The homepages often carry images that show political leaders or school administrators inspecting campus and visiting faculty, staff, or students. This feature graphically exemplifies Confucian notions of veneration for superiors and emphasis on collectivism.

Representing rulers and officials in Chinese culture as revered by common people can be traced back to the beginning of Chinese writing. For example, Classic of Poetry (Gao, 1987), a Confucian classic, composed and compiled between approximately 10th century and 6th century BCE, praises clan leaders as virtuous exemplars, champions of agriculture, and builders of land. In Chinese antiquity, dynastic monarchs were portrayed as authoritative figures setting cultural standards, as we read in Confucius’s (1991) Analects, or as caring rulers sharing pleasures with common people, as we find in Mencius (1991), another Confucian classic.

In my three examinations of the 42 Chinese university websites, at least 38 portray important people, such as government officials and school administrators. These websites portray the important people as the authoritative figures like the rulers in the Confucian classics: They are guiding university work by setting standards, as evidenced by, for example, the websites of Shanghai Jiaotong University and Ocean University of China. These images serve the rhetorical purpose of demonstrating to society that the institutions of higher education are under the leadership of the government and the CPC.

In addition, government officials and school administrators are also depicted as caring leaders who share pleasures with faculty, staff, or students, especially on holidays, as the dynastic monarchs do in Mencius (1991). For example, Tianjin University’s website depicts the secretary of the CPC Tianjin Municipal Committee and the mayor celebrating the Chinese New Year’s Day with faculty and students on campus. This celebration suggests a feeling of friendship and trust between the officials and the faculty and students. They would rather rely on each other’s companionship and joys to spend the most important Chinese traditional holiday than stay with their own families. At a more societal level, this strategy demonstrates that harmony exists on campus, as government officials and faculty and students share ideas and experiences; they simply support each other.

In short, the appearance of the political leaders and school officials on the university homepages sends clear messages that the government officials loom large on campus, that the institutions of higher education are under the leadership of the Party, and that the universities respect these leaders and officials.

Groups of People

In ancient China, masses of people were classified into groups. Records of Rituals (ca. 481–221 BCE), a Confucian classic, classified them into the old, the strong, and the young (Wu & Lai, 1992, p. 529). Confucius (1991) himself classified them into the old, the friends, and the young. As Ames (1983) explains, in ancient China, rulers were expected to “orchestrate the collective energies of the people” to guarantee success (p. 146). In the Chinese tradition, using the collective efforts of groups seems to serve two purposes (Ames, 1983, pp. 143–146). First, rhetorically, it helps generate collective wisdom which cannot be matched by any individuals. Second, at a more societal level, using the collective efforts of groups helps secure a ruler’s success in running the society.

The websites of the Chinese universities value group work, as at least 35 university websites depict large groups of faculty or students. Images portraying large groups of students or faculty on the homepages serve the rhetorical purpose of generating collectivist wisdom. For example, the lead picture on Sichuan University’s homepage depicts a large group of beautifully dressed students performing at China’s Spring Festival Evening Concert, a nationally prestigious show. The message is loud and clear: honor is brought home only through collectivism. More often, group work is emphasized when a university website portrays images of large groups of people attending a CPC conference or other political meetings, as is illustrated by, for instance, the websites of Minzu University of China, East China Normal University, and Yunnan University. Sometimes, groups are represented as studying and practicing the CPC ideology or Xi’s thoughts on socialism. These strategies, at a more societal level, serve to declare that the CPC ideology and Xi’s thoughts are popular among faculty, staff, and students. They collectively practice the CPC ideology and XI’s thoughts. Images of groups of people on the university websites intend to show group solidarity in politics. In this respect, using the collective strengths helps guarantee success in propagandizing the CPC ideology.

It appears that the Chinese universities, like the ancient Chinese rulers using the concerted strengths of groups, rigorously gather the physical and intellectual resources of the faculty and students to create a positive impression that people collectively support and practice the CPC ideology.

Campus Views

In Chinese culture, one issue facing the rulers of ancient China was to maintain social order, so Confucianism “pursued cosmological harmony through thoughtful architecture and land use” (Williams, 1996, p. 669). Driven by this thought, the imperial court was always thought to be the center of the universe, surrounded by various subservient social classes in circles radiating from the center (Wang, 2014; Xiao, 1990). In this way, the walls surrounding cities ensured hierarchical order to reflect Confucius’s cosmological order, thus effecting the “harmonious organization of the cities” (Xiao, 2014, p. 36). The walls and the structures within them “were imbued with the signs of power, authority, and hierarchy” (Samuels & Samuels, 1984, p. 204).

If a city is a small cosmos, then a university is a small city, as Samuel (1986) seems to suggest, as at least 25 university websites in my three examinations illustrate. University walls with various buildings within the walls are imbued with ideology, reflecting university institutional hierarchy. Therefore, the buildings on campus and university walls and gates are not just structures in space but symbols of power, authority, and hierarchy. In China, a university is considered a community of high prestige and reputation where knowledge is generated and where, in Xi’s (2016) words, humans are shaped intellectually and ideologically. It is the center of knowledge and ideological education. The walls mark the boundary of this center, just as the city walls serve to mark the boundaries of various social groups. The university walls with gates serve to delineate insiders and outsiders. So the university websites often portray walls, as illustrated by the websites of Tian Jin University, South China University of Technology, and University of National Defense, just to name a few. A university is at once open and shut, open to the insiders who enter through the open gate, but a restricted physical site for the outsiders who are barred by the walls and the closed gate, sustaining order within the university. As Tang (2011) has pointed out, the walls and gates “imply power, esteem, and stability of Chinese universities” (p. 427), a point Tang brings up but does not pursue in her discussion of using university websites as marketing strategies.

Hierarchically Mapping Virtual Sites of Chinese Universities: A Summary of Content Functions

As my above discussion suggests, Confucianism helps us classify content features on Chinese university websites and these features serve various rhetorical and social purposes. The Chinese university websites could also be “spaces”—virtual sites with their own images, texts, and arguments. As virtual spaces, they offer a unique venue for us to interpret the connections between Confucianism and the visual and verbal compositions on the websites.

These Web content features are actually related to each other in terms of underscoring the CPC leadership in China’s institutions of higher education: The political/national agendas are prioritized on the university websites; university history/tradition historically legitimize the current political/national agendas; political leaders directly provide the CPC leadership by giving instructions; large groups of people practice the CPC ideologies; and university campuses, supposed to be open spaces, are enclosed with walls symbolizing social hierarchies as assigned by the CPC and the government.

By taking a cue from Li’s (2017) and Chen’s (2017) creative use of a traditional Chinese concept of “Nine Regions” represented by nine concentric circles, we can map the virtual sites of the Chinese universities—the five content features—to the ancient Chinese diagram of nine regions. Figure 1 illustrates the locations of these sites in five concentric circles.

The national/political agendas occupy the center of the circles; university history/tradition take the next circle as the site where the political/national agendas are justified historically; portrayals of important people possess the next circle as the site where the leaders inspect university work to ensure the political/national agendas are implemented; large groups of people show up in the next circle as practitioners of the CPC ideology; and campus buildings and structures enjoy the peripheral circle as the site which encloses social elites who implement the political/national agenda.

Implications for Practitioners

In this article, I have shown that Confucianism influences the content features on these Chinese university websites and that these features serve various rhetorical and social purposes to represent the universities. Specifically, the results indicate that, to a large extent, Chinese university websites tend to promote the cultural values of collectivism and demonstrates deference to superiors—two important Confucian philosophical notions. My findings should have several implications for practitioners, particularly those who develop websites for their company branches or offices in China.

First, they should define strategies for creating a content hierarchy on the websites.

Chinese government leaders and high-level administrators are heavily propagandized on the websites (as they are reported and featured in political /national agendas, news, or campus visits). This involvement seems to be one way that Chinese university website developers manage the websites. In this respect, it is China’s version of the “central management system” discussed by Gould et al. (1999), if only to provide and demonstrate standardization of information on the websites. Meanwhile, this involvement suggests that some content is assigned “higher priority” than others. That is, the university websites demonstrate a complex tiered system for granting “privileges” to various content components, thus creating a content hierarchy on the websites. This hierarchy is explicitly reinforced by the functions of the features. The feature that enjoys higher status on the website is highlighted, exhibiting the power and high status endowed by the hierarchy. Therefore, website developers need to rank-order the content and give priority to the content that features collectivism and deference to superiors, like presentations of “overall agendas,” authority endorsement, group theme, traditions, and buildings/nature. More specifically, they should give attention to the following five suggestions:

- Establish a good working relationship with the government, to cover events of nationwide scope like national meetings or to use features that inspire a general sense of pride like national athletic teams wining world championships, or to carry news that features the national, local, or company leaders. Or simply employ features to show the company’s interest in some notion of common good such as nationwide efforts to green the country. This strategy means that the information on the organization’s website corroborates what is endorsed by the authority. Meanwhile, it demonstrates that the company cares for state affairs instead of just pursuing profits.

- Feature government leaders, administrators, or high-level management on the website by publishing their talks or showing their pictures, particularly leaders visiting the company. This feature suggests that the company gives sufficient attention to the superiors and their talks. It also shows the company’s appreciation for the leaders’ inspecting the company and for providing instructions. This approach tells the public that the company shows deference to superiors.

- Make connections between a company’s traditions and its current status. This shows the company has continued to follow for a long time the practices, principles, and beliefs of the company, thus revealing a tradition of endurance of the company’s cultural traits. In this way, people can perceive a consistency of the company’s long-term reputation, thus believing that the company will continue to enjoy the reputation.

- Stress themes of collectivism, such as groups of employees, faculty, students, families, or consumers. Using group themes sends the message to society that the company has the collective support. It also suggests that the company is using the collective strength of the masses.

- Feature company buildings, walls, gates, gardens, and landscapes. By featuring buildings and landscapes, the website developer stresses the reputation and social status of the company. Also the developer highlights the company’s function as an area for collective interactions of its members housed within the buildings. In this respect, featuring buildings and landscapes is not unlike the creation of virtual geographic environment in the project of Virtual London as described by Hudson-Smith et al. (2005) and Virtual Kyoto as presented by Nakaya et al. (2010).

Conclusion

I have shown that Chinese university websites manifest Confucian notions of collectivism and deference to superiors by featuring political/national agendas, stressing history/tradition, portraying important people, depicting groups, and showing campus views. I have also shown that these features serve various rhetorical and social purposes to represent the universities. However, as I have emphasized in the Introduction, Confucianism is just one of several factors that influences the content features of the Chinese university websites. This study also has its limitations, so more research is needed in the future.

Caution

Again, I urge caution with regard to the impact of Confucianism on the design of the Chinese university websites. First, although in this article I emphasize the two Confucian notions as influences on the Chinese university website content, I do not mean to suggest that Confucianism is the only force or that other forces, such as social, marketing, Web design, legal, ideological, are absent or unconnected. Actually, as my review of literature suggests, the marketing factor is another force that influences many website designs, but focusing on these forces is clearly beyond the scope of this article. Second, as my analysis of the five categories of the Web content features suggest, CPC ideology is closely connected with the roles of the two Confucian notions in influencing the Chinese university websites. Ever since the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220CE), Confucianism has been a major philosophy that influences generations of Chinese dynastic governments and they have always used it to claim suzerainty over the entire country (Fung, 1997). The current Chinese government is no exception. In other words, the CPC and its ideologies are heavily influenced by traditional Chinese culture of Confucianism, as Zheng (2010) points out in his book. Indeed, the Communist notions of collectivism and deference to the Party and the state have their roots in the Confucian notions of collectivism and deference to superiors, according to Brown (2001), Callis (1959), Reischauer and Fairbank (1960), and Winfield et al. (2000). However, like the previous dynastic governments who used Confucianism as a governing tool, the current Chinese government seems to employ Confucianism, particularly its notions of collectivism and deference to superiors, as an ideological and rhetorical strategy for demanding the universities to design their websites in such a way as to show deference to the CPC leaders and its ideologies. In this case, the CPC uses Confucianism, in Ching’s (1997) words, “as a double-edged sword” (p. 65). That is to say, while it lends support to the websites that highlight the CPC ideologies and thus legitimize the ideologies, it suppresses others that do not show deference to the ideologies.

Meanwhile, I must also note that we should not assume invariance of local cultural effects, because as business becomes increasingly global, international communication has become a more fluid and individualized practice. Intercultural exchanges have taught communicators to use communication strategies and cultural conventions from different cultures. Many website developers from non-Western regions, such as Asia, have adopted some of the Western cultural assumptions in developing websites (Kim et al., 2009). Meanwhile, as Kjeldgaard and Askegaard (2006) have pointed out, the globalizing forces do not diminish the impacts of local cultures on Internet communication.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

I must also point out that the results of this study are limited in significance because the 42 Chinese universities, though the top universities in China, are only a small portion of the 2,500 some universities in China. Nonetheless, the small portion I have analyzed clearly demonstrates the extent to which Confucianism affects the design of the university websites. This small portion reveals the relationships between Confucianism and Chinese university website design.

In addition, the data used in this study are not longitudinal, but only from one point in time, i.e., spring of 2018. Therefore, they reflect the features on the Chinese university websites as they appeared in spring of 2018. Probably, the results are somewhat limited in scope; thus, I propose that we should look at the results in context and interpret the significance of the results as limited to one specific point in time. In future research, we can expand studies to cover Chinese businesses and organizations and more Chinese universities, perhaps 20 of each from each province, over a period of five years, as Callahan and Herring (2012) performed their study of the webpages of 1,140 universities from 57 countries over five years. We might also examine presentations of information on Western university websites as a foil against which we might foreground patterns in the design of Chinese university websites. In addition, we could also examine the extent to which university websites in other Confucianism-dominant countries and regions are influenced by the two Confucian philosophical notions. All these studies should sharpen our understanding of Chinese university websites as shaped by Confucianism. Finally, it must be emphasized that, despite its limitations, this study serves as a small window into the many relationships between Confucianism and Chinese university websites.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his appreciation to the editor of this journal and the three anonymous reviewers for the time and work they put in to helping revise drafts of this article. This article draws on their ideas and suggestions.

References

Abubaker, A. (2008). The influence of Chinese core cultural values on the communication behavior of overseas Chinese students learning English. Annual Review of Education, Communication & Language Sciences, 5, 105–135.

Alahmadi, T., & Drew, S. (2016). An evaluation of the accessibility of top-ranking university websites: Accessibility rates from 2005 to 2015. In DEANZ Biennial Conference (pp. 224–233).

Ames, R. (1983). The art of rulership: A study in ancient Chinese political thought. University of Hawaii Press.

Askehave, I., & Nielsen, A. E. (2005). Digital genres: A challenge to traditional genre theory. Information Technology & People, 18(2), 120–141.

Baack, D., & Singh, N. (2007). Culture and web communications. Journal of Business Research, 60(3), 181–188.

Babbie, E. R. (2015). The practice of social research. Nelson Education.

Baek, T., & Yu, H. (2009). Online health promotion strategies and appeals in the USA and South Korea: a content analysis of weight-loss websites. Asian Journal of Communication, 19(1), 18–38.

Ban, G. (1986). History of Han dynasty. In Twenty-five Histories (Vols. 1–12). Shanghai Guji Publisher.

Barnum, C. M. (2010). What we have here is a failure to communicate: How cultural factors affect online communication between east and west. In K. St.Amant & F. Sapienza (Eds.), Culture, communication, and cyberspace: Rethinking technical communication for international online environments (pp. 131–156). Baywood.

Bateman, J. A. (2008). Multimodality and genre. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bennet, A., Eglash, R., & Krishnamoorthy, M. (2010). Virtual Design Studio: Facilitating Online Learning and Communication between US and Kenyan participants. In K. St.Amant & F. Sapienza (Eds.), Culture, communication, and cyberspace: Rethinking technical communication for international online environments (pp. 185–205). Baywood.

Brown, C. (2001). Red in red dye: Precedents for Maoism in Chinese culture. Unpublished master’s thesis, Utah State University, Logan. (Dissertation Database Accession No. AAI1406724)

Calabrese, A., Capece, G., Di Pillo, F., & Martino, F. (2014). Cultural adaptation of web design services as critical success factor for business excellence: A cross-cultural study of Portuguese, Brazilian, Angolan and Macanese web sites. Cross Cultural Management, 21(2), 172–190.

Callahan, E. (2005). Cultural similarities and differences in the design of university web sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(1), 239–273.

Callahan, E. (2007). Cultural differences in the design of human-computer interfaces: A multinational study of university websites (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuestDissertations and Theses database.

Callahan, W., & Herring, S. (2012). Language choice on university websites: Longitudinal trends. International Journal of Communication, 6, 322–355.

Callis, H. (1959). China: Confucian and communist. Holt.

Chan, W. (1998). A source book in Chinese philosophy (4th ed.). Princeton University Press.

Charlesworth Group (2017, October 3). New Chinese Double First Class University Plan released. https://cwauthors.com/article/double-first-class-list

Chen, G. (1997, November). An examination of PRC business negotiating behaviors. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Communication Association, Chicago. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED422594)

Chen, J. (2017) Sites I. In W. Denecke, W. Li, & X. Tian (Eds.). Classical Chinese literature (1000 BCE–900 CE) (pp. 424–437). Oxford University Press.

Ching, J. (1997). Mysticism and kingship in China the heart of Chinese wisdom. Cambridge University Press.

Choudaha, R., & Chang, L. (2012). Trends in international student mobility. World Education News & Reviews, 25(2), 1–5.

Confucius. (1991). Annotations of four books (X. Zhu, Ed.). Zhonghua Book Press. (Original work published 1190.)

Cooper-Chen, A. (1995, August). The second giant: Portrayals of women in Japanese advertising. Paper presented at the meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication Annual Convention, Washington, DC.

CPC. (2017). Education in “Two Studies and One Make.” Communist party member network. http://www.12371.cn/

CPC. (2018). Lu Jian appointed president of Nanjing University (rank of deputy minister). Nanjing University news network. http://news.nju.edu.cn/show_article_2_48515

CPC and the State Council. (2017). Strengthen and improve ideological and political work in the institutions of higher education. http://news.sciencenet.cn/htmlnews/2017/2/369076.shtm

CSIS. (2018). Is China both a source and hub for international students? China power project. https://chinapower.csis.org/china-international-students/

Davis, B., Chen, T., Peng, H., & Blewchamp, P. (2010). Meeting each other online: Corpus based insights on preparing professional writers for international settings. In K. St.Amant & F. Sapienza (Eds.), Culture, communication, and cyberspace: Rethinking technical communication for international online environments (pp. 157–182). Baywood.

Denecke, W. (2017). Literature and metaliterature. In W. Denecke, W. Li, & X. Tian (Eds.), Classical Chinese literature (1000 BCE–900 CE) (pp. 342–346). Oxford University Press.

Ding, D. (2006). An indirect style in business communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 20(1), 87–100.

Ding, D. D. (2010). Pleasure in naming all the parts of the known in their expected order: How traditional Chinese agrarian culture influences modern Chinese cyberspace communication. In K. St.Amant & F. Sapienza (Eds.), Culture, communication, and cyberspace: Rethinking technical communication for international online environments (pp. 111–129). Baywood.

Dormann, C., & Chisalita. C. (2002). Cultural values in website design. Paper presented at the Eleventh European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics, Catania, Italy.

Durrant, S. (2017). Tradition formation: Beginnings to Easter Han. In W. Denecke, W. Li, & X. Tian (Eds.), Classical Chinese literature (1000 BCE–900 CE) (pp. 377–386). Oxford University Press.

Farnsworth, K. (2005). A New Model for Recruiting International Students: The 2+2. International Education, 35(1), 5–14.

Fung, Y. (1997). A short history of Chinese philosophy (3rd ed., D. Bodde, Tran.). Free Press.

Gardner, D., & Witherell, S. (2007). Open doors 2007: International students enrollment in US rebounds. Institute of International Education. http://opendoors.iienetwork.org/?p¼113743

Google. (2018). Google Scholar. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C23&q=Crosscurrents%3A+cultural+dimensions+and+global+Web+user-interface+design&btnG=

Gao, H. (Ed.). (1987). New commentary on Classic of Poetry. Shanghai Classics Publishing House.

Hartley, M., & Morphew, C. (2008). What’s being sold and to what end? A content analysis of college viewbooks. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(6), 671–691.

Hawes, C. (2008). Representing corporate culture in China: Official, academic and corporate perspectives. The China Journal, 59, 33–61.

He, Z., Bu, J., Tang, Y., & Sun, K. (1982). A history of Chinese thoughts. Chinese Youth Press.

Herr, R. (2003). Is Confucianism compatible with care ethics? A critique. Philosophy East & West, 53, 471–489.

Herring, S. C., Scheidt, L. A., Kouper, I., & Wright, E. (2007). Longitudinal content analysis of blogs: 2003–2004. Blogging, citizenship, and the future of media, 3–20.

Hillier, M. (2003). The role of cultural context in multilingual website usability. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 2(1), 2–14.

Hofstede, G. (1997). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of themind. McGraw-Hill.

Hsu, S., & Barker, G. (2013). Individualism and collectivism in Chinese and American television advertising. International Communication Gazette, 75(8), 695–714.

Huang, Q., Andrulis, R. S., & Chen, T. (1994). A guide to successful relations with the Chinese: Opening the Great Wall’s gate. International Business Press.

Hudson-Smith, A., Evans, S., Batty, M. (2005). Building the virtual city: Public participation through e-democracy. Knowledge, Technology & Policy, 18(1), 62–85.

ICEF. (2017, October 4). China announces new push for elite university status. http://monitor.icef.com/2017/10/china-announces-new-push-elite-university-status/

John, T. (2016, November 14). International students in US colleges and universities top 1 million. Time. http://time.com/4569564/international-us-students/Google Scholar

Kjeldgaard, D., & Askegaard, S. (2006). The glocalization of youth culture: The global youth segment as structures of common difference. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(2), 231–237.

Kim, H., Coyle, J. R., & Gould, S. J. (2009). Collectivist and individualist influences on website design in South Korea and the US: A cross-cultural content analysis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14(3), 581–601.

Kirppendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). Sage.

Lasswell, H. D. (2017). The Signature of power: Buildings, communications, and policy. Routledge.

Lawson-Borders, G., & Kirk, R. (2005). Blogs in campaign communication. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(4), 548–559.

Leibold, J. (2010). More than a category: Han supremacism on the Chinese internet. The China Quarterly, 203, 539–559.

Li, W. (2017). Moments, sites, and figures: Editor’s introduction. In W. Denecke, W. Li, & X.

Tian (Eds.), Classical Chinese literature (1000 BCE–900 CE) (pp. 399–401). Oxford University Press.

Liao, C., To, P. L., & Shih, M. L. (2006). Website practices: A comparison between the top 1000 companies in the US and Taiwan. International Journal of Information Management, 26(3), 196–211.

Lu, S. (2016). History of Chinese culture. Lujiang Publishing House.

Lu, Ning. (2017). “The Little Red Book lives on: Mao’s rhetorical legacies in Contemporary Chinese Imaginings.” In S. Hartnette, L. Keranen, & D. Conley (Eds.), Imagining China: Rhetorics of Nationalism in an age of globalization (pp. 11–45). Michigan State University Press.

Marcus, A. (2003). Global/intercultural user interface design. In A. Sears, & J. Jacko (Eds.), Human Computer Interaction Handbook: Fundamentals, evolving technologies, and emerging applications (2nd ed., pp. 441–463). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Marcus, A., & Gould, E. W. (2012). Globalization, localization, and cross-cultural. In J. Jacko (Ed.), Human Computer Interaction Handbook: Fundamentals, evolving technologies, and emerging applications (3rd ed., pp. 341–366). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mencius. (1991). Mencius. (D. C. Lau, Tran.). New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Nakaya, T., Yano, K., Isoda, Y., Kawasumi, T., Takase, Y., Kirimura, T., Tsukamoto, A.,

Matsumoto, A., Seto, T., & Iizuka, T. (2010). Virtual Kyoto project: Digital diorama of the past, present, and future of the historical city of Kyoto. In T. Ishida (Ed.), Culture and Computing (pp. 173–187). Springer.

Okazaki, S., & Alonso Rivas, J. (2002). A content analysis of multinationals’ Web communication strategies: cross-cultural research framework and pre-testing. Internet Research, 12(5), 380–390.

Paek, H. J. (2005). Understanding celebrity endorsers in cross-cultural contexts: A content analysis of South Korean and US newspaper advertising. Asian Journal of Communication, 15(2), 133–153.

Qiu, J., Chen, J., & Wang, Z. (2004). An analysis of backlink counts and web Impact Factors for Chinese university websites. Scientometrics, 60(3), 463–473.

Reischauer, E., & Fairbank, J. (1960). A history of East Asian civilization. Houghton Mifflin.

Saichaie, K., & Morphew, C. C. (2014). What college and university websites reveal about the purposes of higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(4), 499–530.

Samuels, C. (1986). Cultural ideological and the landscape of Confucian China: The traditional si he yuan (master’s thesis). https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0097135

Samuels, M., & Samuels, C. (1989). Beijing and the power of place in modern China. In J. Agnew & J. Duncan (eds.), The power of place: Bringing together geographical and sociological imaginations (pp. 202–227). Unwin Hyman.

Simon, S. J. (2000). The impact of culture and gender on web sites: an empirical study. ACM SIGMIS Database: the DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 32(1), 18–37.

Singh, N. (2003). Culture and the World Wide Web: a cross-cultural analysis of web sites from France, Germany and USA. In American Marketing Association, 14, (pp. 30–31).

Singh, N., & Martinengo, R. (2015). Studying cultural values on the web: a cross-cultural study of US and Mexican Web Sites. In Proceedings of the 2002 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference (pp. 146–146). Springer.

Singh, N., Kumar, V., & Baack, D. (2005). “Adaption of cultural content: A webmarketing focus.” European Journal of Marketing, 39(1–2), 71–86.

Singh, N., & Matsuo, H. (2004). Measuring cultural adaptation on the Web: a content analytic study of US and Japanese Web sites. Journal of Business Research, 57(8), 864–872.

Singh, N., Zhao, H., & Hu, X. (2003). Cultural adaptation on the web: A study of American companies’ domestic and Chinese websites. Journal of Global Information Management (JGIM), 11(3), 63–80.

Singh, N., Zhao, H., & Hu, X. (2005). Analyzing the cultural content of web sites: A cross-national comparison of China, India, Japan, and US. International Marketing Review, 22(2), 129–146.

St.Amant, K. (2005). A prototype theory approach to international website analysis and design. Technical Communication Quarterly, 14(1), 73–91.

St.Amant, K. (2010). Culture, cyberspace, and the new challenges for technical communicators. In K. St.Amant & F. Sapienza (Eds.), Culture, communication, and cyberspace: Rethinking technical communication for international online environments (pp. 1–9). Baywood.

Tang, T. (2011). Marketing higher education across borders: a cross-cultural analysis of university websites in the US and China. Chinese Journal of Communication, 4(4), 417–429.

Trammell, K. D., & Keshelashvili, A. (2005). Examining the new influencers: A self-presentation study of A-list blogs. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 82(4), 968–982.