By Regan Joswiak and Mike Duncan

ABSTRACT

Purpose: We examined how 10 best-selling technical communication textbooks delineated “informative” and “persuasive” purposes in discourse and, in response, suggest a more effective pedagogical alternative to this typical division that instead consistently emphasizes the rhetorical nature of all communication.

Method: We conducted a semantic analysis of 10 best-selling technical communication textbooks and present findings regarding the appearance of terms related to “informative” and “persuasive” concepts in three types of documents or genres: general discussions, reports, and presentations. To demonstrate the problematic findings in these books, we also examine and summarize recent literature in rhetoric and technical communication.

Results: Overall, a delineation of some sort between “informative” and “persuasive” communication was typically present, which—as literature in rhetoric and technical communication shows—contradicts practitioners’ roles as persuasive communicators. While some of the examined textbooks emphasized persuasion in their general discussions, this emphasis became inconsistent when they discussed oral presentations, and the genre of report-writing in particular lacked discussion about its persuasive elements.

Conclusion: We recommend a more complex, rhetorical, and consistent understanding of discourse that rejects an artificial divide between “informative” and “persuasive” in future technical communication textbooks and editions, especially in regard to all workplace communication.

Keywords: informative, persuasive, pedagogical theory, rhetorical theory, academy-industry conflicts

Practitioner’s Takeaway

The common division between “informative” and “persuasive” discourse in technical communication textbooks ignores a substantial shift in rhetorical theory since the early 1970s that regards all communication as persuasive to some degree—including texts that claim to be “informational.”

The discourse divisions and overall inconsistent discussions about documents present in Johnson-Sheehan’s (2018) Technical Communication Today, the primary text for the Society for Technical Communication’s Foundation Certification, fail to provide practitioners the rhetorical, persuasive perspectives that are necessary in their roles as technical communicators.

The writers of future editions and new textbooks, as well as teachers of technical communication, should reconsider the use of these distinctions in favor of a more holistic rhetorical treatment of technical communication.

Introduction

Students in technical communication are often taught to view all discourse rhetorically; persuasion, according to instructors, is an essential part of communication both inside and outside the workplace. However, equally often, students are also taught that there is a difference between “informing” and “persuading.” We submit that not only is there a dated conflict in the field between these two actions and concepts, but there is also a serious issue between these terms and technical communication pedagogy. We share Miller’s (1979) concern that “our pedagogy is weakened by submerged inconsistencies and contradiction” (p. 616) and, as a result, we explore these problems by closely examining 10 best-selling technical communication textbooks to analyze how the authors define and discuss these key terms. We then argue that a more consistent, theoretical, and practical presentation of rhetorical discourse in technical communication textbooks—namely, one that emphasizes the persuasive nature of all communication, including the seemingly “informative”—is needed to encourage students to view discourse through a rhetorical lens and to also better prepare them in their future roles as professional, persuasive communicators.

A Brief History of Discourse Division

Dividing discourse by purpose is as old as Cicero’s (55 BCE/2001) De Oratore, which was an oversimplification of complex speeches that often performed all three “offices” of instruction, pleasure, and persuasion. Such divisions were convenient because they rendered rhetoric easier to understand and teach; this quality was not lost on the various later developers of the “modes of discourse,” which can be traced directly to Latin rhetoric instruction, and were first codified in English in the 19th century. With the division of discourse into the four categories of narration, description, exposition, and argument, the complexities of writing were distilled into four neat pedagogical boxes, three-quarters of which did not contain any argument or persuasive element. The popularity and decline of these divisions in English writing pedagogy were well documented by Connors (1981), and his closing words are as valuable today: “The real lesson of the modes is that we need always to be on guard against systems that seem convenient to teachers but that ignore the way writing is actually done” (p. 455).

But pedagogical efficiency was not the only possible motive for dividing or classifying discourse. As Manolescu (2007) described, Campbell’s 1776 Philosophy of Rhetoric created a special “factual” category for testimonial evidence because he wanted the Christian gospels to be treated as factual rather than as persuasive. In a different but parallel way, as explained by Harned (1985), Bain’s 1866 landmark English Composition and Rhetoric—whose prescriptive compositional structures make our modern technical communication textbooks seem free-form in comparison—was driven by association psychology and the premise that “all minds think alike” (p. 50) and, accordingly, that all students could be taught mechanistically through modes. These two stances—that some discourse gets waved through as innocent of persuasion and that rigid theory rather than practice should drive pedagogy—are particularly problematic now, however, because of the ascent of the rhetoric of science subfield that has shown how the supposedly objective practice of scientific research is inherently rhetorical (Bazerman, 1988; Gross, 1996; Kuhn, 1962; Toulmin, 2003).

The issue of discourse categorizations surfaced again with Kinneavy’s (1971) A Theory of Discourse and the responses to his work. Dividing his book’s chapters to separately examine each aim, Kinneavy discussed reference discourse, an emphasis on reality; persuasive discourse, an emphasis on the decoder or audience; literary discourse, an emphasis on the product; and expressive discourse, an emphasis on the encoder or communicator (pp. 38–39). Kinneavy argued that while these different purposes and their uses need to be studied separately, as “each of these uses of language has its own process of thought,” the “aims overlap just as the modes of discourse [overlap]” (p. 40). He also emphasized the prominent role of persuasion in communication during his introduction to persuasive discourse, stating, “it is doubtful if any area of discourse is immune to persuasion” (p. 218).

Kinneavy’s (1971) chapter on expressive discourse underwent the most scrutiny, as critics found the distinction of the aim and the analyses used to demonstrate it questionable. Freeman (1973), for example, noted that Kinneavy attempted to explain the aim since it “obviously intrudes on, influences, and incorporates other kinds of discourse,” but the chapter was “more tentative” than others (p. 231). He also pointed to Kinneavy’s analysis of The Declaration of Independence as an expressive document and how “no one would deny the manifest self-expression of the desires of a people in this document, but it is also informative, certainly persuasive, and maybe a bit exploratory” (p. 231). O’Banion (1982) argued, similarly, that because Kinneavy ignored the rhetorical process of creating a text and instead developed a discussion that centered on static texts, there became “an unfortunate separation of the kinds of discourse,” with The Declaration of Independence’s persuasive elements being ignored (p. 199). Fulkerson (1984) added that the large structure of the document is deductive, since it contains conclusions drawn from premises, and noted that Kinneavy himself listed deduction as a feature of scientific discourse (a subcategory of reference discourse), which undermines his own analysis of The Declaration of Independence as expressive discourse.

Kinneavy’s (1971) claim about a text’s purpose (or aim) determining its structure was also considered problematic. To demonstrate issues with Kinneavy’s claim, Fulkerson (1984) examined Golding’s “Thinking as a Hobby” and explained that the essay is similar in structure to a scientific text, but “uses the classificatory mode in the service of exploratory or expressive aims” (p. 48). Fulkerson concluded, “Clearly then ‘aim’ in the broad sense does not determine structure, since several discourses with the same structure may have very different aims, and since pieces with the same general aim may have very different structures” (p. 48). As others have also discussed (Knoblauch & Brannon, 1984; Walzer, 1991), the taxonomic view that Kinneavy aligned with—the perspective that connects purpose to genre and, as a result, treats a text’s features as identifiable qualities of that purpose—is questionable. Knoblauch and Brannon (1984), in particular, challenged the taxonomic view and the generic purposes that classical rhetoric focuses on; instead, they argued that writers respond to multiple purposes, and “writers evolve and invoke operational purposes in the course of writing, specific and localized motives for choosing one sort of information over another” (p. 67).

Like Knoblauch and Brannon (1984) and their criticisms of generic purposes, Keith (1997) also cautioned against discourse classifications and considered the traditionally taught purposes of communication, or officia, to be “too crude for more practical purposes,” and warned that “they invite a serious mistake” (p. 305). Keith argued that the distinctions between persuasion, instruction, and entertainment can fall prey to practices that impact the effectiveness of the discourse, particularly with instruction: “Sometimes, instruction, or as we might say ‘informative communication,’ is contrasted with persuasion, and the logic criticized above is engaged: ‘Well, I’m just trying to convey information, nothing more, so the subject matter (information) will dictate all the important choices’” (pp. 305–306). The mistake here, according to Keith, is that other important considerations or limitations, such as audience, roles, and ethos, can be ignored with the classification of “informative” communication.

Post-Kinneavy Conflict

If anything, Kinneavy’s (1971) work and the criticisms of it, and the criticisms of discourse classifications, demonstrate the problem with our field’s discussions of aim and purpose: While no one disagrees that the informative and persuasive aims of discourse overlap (Kinneavy, 1971, p. 60), there is nonetheless an ongoing issue with textbook authors demonstrating how the aims overlap. Ultimately, Kinneavy’s treatment of purpose encourages a categorization of discourse that dissuades the reader from seeing the discourse beyond the categorization. As O’Banion (1982) argued, “By making only a few attempts at indicating the interrelationship of the discursive aims, and by treating each aim so independently that each chapter seems like a new beginning, Kinneavy unfortunately isolates what should be synthesized” (p. 200).

The most troubling aspect of this issue, however, is the conflict that occurs when instructors emphasize the rhetorical nature of all communication to students and then persist in distinguishing between “informative” and “persuasive” documents. Because all communication is rhetorical to some degree (Kinneavy, 1971, p. 218), the common divisions between informative and persuasive discourse are unhelpful and impractical, as writers “would be better off seeing themselves as persuasive” (Keith, 1997, p. 306). Kynell (1994) partially explored this problem in textbooks by studying five editions of Lannon’s textbook Technical Writing to determine how the field of technical communication has evolved over time, concluding that the discipline has shifted throughout the years to emphasize more persuasion and audience analysis. However, no other explorations such as Kynell’s (1994) exist in the literature.

From the perspective of rhetorical theory, the “all communication is rhetorical” stance is firmly in the so-called “big rhetoric” camp, defined well by Schiappa (2001) as “the theoretical position that everything, or virtually everything, can be described as ‘rhetorical’” (p. 200). We hold to less than that—namely, that all communication is rhetorical, not everything—but both positions came under fierce critique in the 1990s. Schiappa’s article provided a solid summation of the major debate, as well as the origins of “big rhetoric” in the seminal work of Weaver (1985) and Burke (1969), and he dismissed the objections of the “little rhetoric” critics, especially the common “if everything is rhetoric, nothing is” counterargument (pp. 268–272). Fourteen years later, McKerrow (2015), reviewing current rhetoric research, portrayed Schiappa’s (2001) piece as a decisive final defense (pp. 154–156). In our experience, however, there is still much informal debate on this issue among rhetoricians, especially technical communication experts.

Research Design

For our analysis, we selected 10 technical communication textbooks to examine how informative and persuasive discourse were discussed and defined. As Matveeva (2007) stated, “textbooks give instructors various pedagogical tools and materials for classroom discussions and activities, and textbooks are essentially what students buy, read, and use in learning. At least to a significant extent, textbook contents form technical writing pedagogy” (p. 151). Because textbooks “form technical writing pedagogy” (p. 151), it is pertinent to examine technical communication textbooks to develop a greater understanding of what technical communication students are learning.

What students are learning also has implications that extend outside of academia, as it is likely they transfer the information into other professional environments. According to Brady (2007), who conducted a qualitative study about what scientific and technical communication students used from their academic settings as they transitioned into their workplace environments, students can rely on the problem-solving and composing strategies they were taught from their textbooks and educators as they find themselves in new, unfamiliar professional environments. Given these implications, an analysis of what technical communication students are taught about informative and persuasive approaches is overdue.

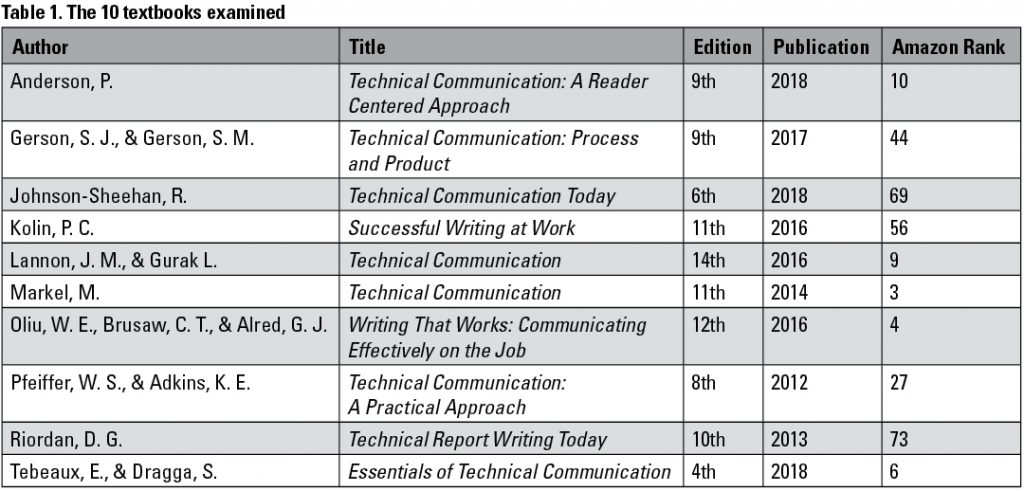

The textbooks we selected for this study were published between 2012 and 2018. All of the textbooks have a generalist focus, and the selection was based on longevity and popularity. To determine the popularity of the textbooks, we referred to the sales-ranking system of Amazon.com for a list of best-selling textbooks under the category of “Best-Sellers in Technical Writing Reference.” Under this category, Amazon lists 100 best-sellers, and the list is updated hourly. Because the category includes reference books and textbooks beyond a generalist focus, we referred to the list of textbooks that Boettger and Wulff (2014) used for their analysis, which was based on Wolfe’s (2009) analysis, for textbooks to compare to Amazon’s category. We then selected the textbooks from these studies that appeared on Amazon’s best-selling list, which demonstrates their continued popularity since the publication of the authors’ analyses.

Most of the selected textbooks are in the 9th edition or later, which shows longevity in the classroom, particularly because all also appeared in Boettger and Wulff’s (2014) or Wolfe’s (2009) studies. We would like to note that because Amazon updates the rankings hourly—and because the category includes textbooks beyond a generalist focus, reference material, and different editions of the same textbooks—the specific ranking of each textbook is not critical to our study, though we provide the rankings for reference (Table 1). The authors who consistently ranked within the top 15 during this study were Markel (2014); Lannon and Gurak (2016); Oliu et al. (2016); Anderson (2018); and Tebeaux and Dragga (2018). The remaining authors ranked in the top 25–75. The list was last accessed on August 26, 2018.

To gain insight on how informing and persuading is taught to technical communication students, our textbook analysis was semantic. In the selected textbooks, we looked for terms such as “inform,” “informative,” “informational,” “persuasive,” “persuade,” “persuasion,” and other permutations by examining indexes, the table of contents, and chapters, including examples and checklists. Then, we created categories to make distinctions between how the authors discussed the terms. We categorized the data as follows:

- General discussions, which includes how the authors introduced “persuasive” and “informative” elements, definitions, or documents.

- Reports, which includes discussions about informative/informational reports, progress reports, and scientific or empirical research reports.

- Oral presentations, which includes discussions about “informative” or “persuasive” presentation types.

The reason for such categorizations is because of a distinctive pattern that emerged as we searched for the terms in the textbooks; it was apparent throughout the course of the analysis that, in addition to the introductory materials dedicated to the concepts, these terms were frequently connected to types of reports and oral presentations.

The reason for such categorizations is because of a distinctive pattern that emerged as we searched for the terms in the textbooks; it was apparent throughout the course of the analysis that, in addition to the introductory materials dedicated to the concepts, these terms were frequently connected to types of reports and oral presentations.

Results

In the following sections, we provide the results and analysis of the discourse in each of the three categories.

General Discussions

The analysis of the textbooks revealed many differing discussions about “informing” and “persuading.” Two of the textbooks (Kolin, 2016; Tebeaux & Dragga, 2018) emphasized persuasion rather than creating and defining a category for informative documents. Kolin (2016), for example, stated that there are six basic functions of writing: “(1) to provide practical information, (2) to give facts rather than impressions, (3) to supply visuals to clarify and condense information, (4) to give accurate measurements, (5) to state responsibilities precisely, and (6) to persuade and offer recommendations” (p. 20). Rather than divide the information further, however, he emphasized persuasion’s importance. For example, he stated, “Persuasion is a crucial part of writing on the job. In fact, it is one of the most valuable skills you need in the business world” (p. 23). Similarly, Tebeaux and Dragga (2018) made the statement that “all writing is persuasive: It must convince the reader(s) that the writer has credibility and that the writer’s ideas have merit” (p. 226). The other textbooks did not communicate a position as easily distinguishable, however.

Five of the textbooks (Gerson & Gerson, 2017; Johnson-Sheehan, 2018; Lannon & Gurak, 2016; Oliu et al., 2016; Riordan, 2013) divided persuasive information from other forms of writing. Riordan (2013), Lannon and Gurak (2016), and Gerson and Gerson (2017) discussed how communication has the purpose to inform, instruct, or persuade. Despite these divisions, Lannon and Gurak stated, “Almost all workplace documents, to some extent, have an implicitly persuasive goal” (p. 34, emphasis in original). Riordan, however, asserted that “most writers use technical writing to inform” (p. 6) and failed to discuss whether there is an overlap between informative and persuasive goals. Because he stated that technical writing is used to inform—with the implication that this is its purpose—the overlap is even less clear. Additionally, in Riordan’s “Worksheet for Planning” checklist, he posed a question: “Why do I need to convey that message? To inform? To instruct? To persuade?” (p. 66). The lack of a combination option leaves the impression that the types are completely separate.

Under Gerson and Gerson’s (2017) “Determining Your Goals” section, they listed similar categories: inform, instruct, persuade, and build trust and rapport. The most problematic section is when the authors gave examples of informative communication. They stated, “Often, you will write letters, reports, and e-mails merely to inform” (p. 38). With this statement, the authors created a false division between informing and persuading, and ignored the implicit persuasion in these types of correspondence. Oliu et al. (2016) communicated a similar division, though they only made distinctions between instruction and persuasion. For example, when illustrating different types of writing, they stated, “Although the purpose of the maintenance manual is to instruct rather than to persuade the audience, its organization differs from that used for the sales brochure” (p. 38). Such statements fail to communicate persuasion’s role in documents.

Unlike the other four authors, Johnson-Sheehan (2018) introduced informative and persuasive categorizations through verb lists in his first chapter when he discussed how to create a purpose statement. He provided a list of action verbs under each of the headings of “Informative Documents” and “Persuasive Documents” that expressed the purpose of the document, and he also delineated between plain and persuasive style. In a later chapter dedicated to these styles, Johnson-Sheehan explained that “there are times when you will need to influence people to accept your ideas and take action” and “in these situations persuasive style allows you to add energy and vision to your writing and speaking” (p. 450). However, he also noted, “In a sense, all forms of scientific and technical communication are persuasive in some way” (p. 367). While it is important that Johnson-Sheehan made a distinction between the different tones and styles of various documents, explaining the topic in these ways confuses the issue because the first chapter prepares the reader for an unnecessary division between the two, while later chapters discuss an overlap between the terms.

The remaining textbooks (Anderson, 2018; Markel, 2014; Pfeiffer & Adkins, 2012) used diverse language to describe the functions of documents and used terms other than “informative” or “persuasive.” For example, Anderson (2018) categorized a document’s function with the terms “useful,” which he stated dominates instructions, and “persuasive,” which he stated dominates proposals. However, according to Anderson, “Every workplace communication must possess both to succeed” (p. 9). While Anderson made the connection between the two clear, this connection was not explicitly stated in other textbooks.

Pfeiffer and Adkins (2012) provided a “continuum” of determining a purpose, which was between a “neutral, objective statement” and a “persuasive, subjective statement,” and stated a writer’s purpose will “fall somewhere within this continuum” (p. 38). They offered examples of neutral messages, such as a “letter inviting the reader to an event” (p. 164), but this example is not a neutral request. In an invitation to an event, the language itself may not be strongly persuasive (which is how they defined the persuasive category), but all invitations are inherently persuasive because of their purpose: to entice the reader to attend an event, or at least to acknowledge the event and account for its existence.

Markel (2014) provided another example of delineating between informative and persuasive approaches: He created categories for verbs that depend on the reader’s purpose, differentiating between “communicating verbs” and “convincing verbs.” Markel described the verbs as “those used to communicate information to your readers and those used to convince them to accept a particular point of view” (p. 108). Markel added, “Sometimes, of course, you can have several purposes” (p. 108). However, creating these distinctions misleads readers into thinking that they can create documents that are free from persuasion.

Reports

Like the general discussions of informative and persuasive information, the textbooks we examined had vastly different perspectives about the persuasive status of reports. Specifically, the terms we searched for emerged in informative/informational reports, progress reports, and scientific or empirical research reports. These discussions ranged from directly stating that these reports are persuasive documents to only describing them as informative in nature.

All of the textbooks that discussed “informational” or “informative” reports discussed them without mentioning how the documents operate on a persuasive level. Pfeiffer and Adkins (2012), Markel (2014), Lannon and Gurak (2016), and Gerson and Gerson (2017) devoted sections to reports, and all explained how reports inform the audience. For example, Pfeiffer and Adkins (2012) described informative reports as “a means of conducting daily operations and record keeping in organizations” (p. vii), and Lannon and Gurak (2016) stated that “these reports help keep an organization running from day to day by providing short, timely updates” (p. 473). Markel (2014) described them similarly: “Informational reports share one goal: to describe something that has happened or is happening now. Their main purpose is to provide clear, accurate, specific information to an audience” (p. 446). Finally, Gerson and Gerson (2017) stated, “Informational reports focus on factual data. They are often limited in scope to findings: ‘Here’s what happened’” (p. 403). Collectively, these authors emphasized how these reports provide or record information and excluded persuasive terminology.

Interestingly, even though Pfeiffer and Adkins (2012) neglected to discuss informative reports in general as operating persuasively, they did make this distinction with progress reports: “Progress reports contain mostly objective data. Yet they are sometimes written in a persuasive manner. Progress reports tell your supervisor or the client that your project is on task, on time, and on budget” (p. 355). It should be noted that the authors stated progress reports are “sometimes” written this way, but not always. This definition differs greatly from Tebeaux and Dragga’s (2018), which stated, “Keep in mind that proposals and progress reports are persuasive documents. You write to convince your reader of the merit and integrity of your work” (p. 222). Anderson (2018) provided a similar discussion with progress reports and stated that “generally, you want to persuade your readers that you are doing a good job” (p. 456). In his “Writer’s Guide for Revising Progress Reports” at the end of the chapter, he also asked, “Does your draft include each of the elements needed to create a report that your readers will find to be useful and persuasive?” (p. 457).

Gerson and Gerson (2017) also used the report as an example of persuasive communication, though they only did so in a chapter under their “Communicating to Persuade” section, and stated, “Maybe you will write your annual progress report to justify a raise or a promotion.” (p. 38). In their progress report chapter, they stated that the document can “inform your reader(s) of any difficulties encountered” (p. 420). Given the persuasive nature of progress reports, the discussion would have been more effective if the authors included persuasion under the report’s description. This said, Gerson and Gerson, along with Tebeaux and Dragga (2018) and Anderson (2018), are the only authors to include how progress reports are persuasive. Other authors either stated that the report is a document that “informs” its audience about a project (Johnson-Sheehan, 2018; Kolin, 2016; Lannon & Gurak, 2016; Oliu et al., 2016; Riordan, 2013) or defined it without using informative or persuasive terminology (Markel, 2014).

The authors also discussed scientific reports—lab reports, specifically—or empirical research reports. One author, Anderson (2018), used persuasive terms that appeared in his discussion about empirical research reports. In his “Writer’s Guide for Revising Empirical Research Reports,” he listed “persuades readers that this research is important to them” and “presents information in a clear, useful, and persuasive manner” (p. 427) on his checklist. The majority of the authors who used informative or persuasive terms, however, discussed lab reports (Markel, 2014; Pfeiffer & Adkins, 2012), and one author (Johnson-Sheehan, 2018) discussed both lab reports and scientific reports separately.

While Johnson-Sheehan (2018) discussed both scientific reports and lab reports, he presented contradicting information in his style sections for each. In the “Brief Reports” chapter, which contained both progress reports and lab reports, he described the style of the documents: “Generally, brief reports follow a plain style and use a simple design. These documents are mostly informative, not overly persuasive, so you should try to keep them rather straightforward” (p. 298). Then, in a separate chapter titled “Formal Reports,” he discussed scientific reports. Under the heading “Using Plain Style in a Persuasive Way,” which followed the definition of scientific reports, he stated, “Reports are persuasive in an unstated way, putting the emphasis on the soundness of methodology, the integrity of the results, and the reasonableness of the discussion” (p. 340). Because scientific reports and lab reports share the same structure for reporting information, the persuasion that he discussed as a part of the methodology, results, and discussion for scientific reports should also have been discussed for lab reports. Furthermore, he described lab reports (and progress reports) as having a plain style and failed to mention how plain style can be used persuasively with lab reports, though he did so with scientific reports, as though they are unrelated documents.

Markel (2014), however, stated the lab report’s persuasive function: “At first glance, a lab report might appear to be an unadorned presentation of methods, data, and formulas. It isn’t. It is a carefully crafted argument meant to persuade an audience to accept your findings and conclusions” (p. 516). He also stressed the importance of persuasion for the scientific community. According to Markel, if scientists and engineers “want to contribute to their fields, they must convince readers that their findings are valid. For this reason, the ability to write clearly and persuasively is both necessary and valued in the sciences and engineering” (p. 517). Pfeiffer and Adkins (2012), however, offered a description opposed to Markel’s (2014): “Lab reports record and communicate the results of laboratory studies; therefore, they are primarily informative” (p. 358). Although they stated lab reports are “primarily” informative—implying a potential to be persuasive—they leave persuasion out of the conversation. Because it is common to regard reports as informative documents, it is noteworthy that only Markel and Anderson (2018) defined lab reports as persuasive documents, and only Johnson-Sheehan (2018) defined scientific reports as persuasive documents, though with contradictions.

Oral Presentations

Most of the textbooks separated oral presentations into informative and persuasive categories, regardless of how the authors discussed persuasion in earlier sections or chapters. Pfeiffer and Adkins (2012) and Riordan (2013), however, described presentation techniques without creating informative or persuasive divisions, along with Johnson-Sheehan (2018). Instead, Johnson-Sheehan’s “Presenting and Pitching Your Ideas” chapter focused on providing information about presentation considerations and strategies, and he stated that “even when you aren’t making a presentation or pitching new ideas, you will still need to speak clearly and persuasively” (p. 554). When he discussed defining a presentation’s purpose, he provided examples such as, “My goal is to persuade elected officials that climate change is a looming problem for our state,” and then stated, “For more help on defining your purpose, go to Chapter 1” (p. 556). If students refer back to Chapter 1, however, they encounter the divisions between informative and persuasive documents, which then transfers this dichotomy to speech.

Four other textbooks (Anderson, 2018; Gerson & Gerson, 2017; Lannon & Gurak, 2016; Markel, 2014) implied or stated that readers could have a dual purpose of informing and persuading. Of the four authors, the only one who communicated a clear overlap amongst the four books was Anderson (2018), who used the terms “useful” and “persuasive” to describe oral presentations, as he previously did with written communication in his introductory chapter. He stated that “even the most overtly persuasive presentations” will include information the audience can “use” to make to decisions (p. 355). Additionally, in his “Writer’s Guide for Creating and Delivering Oral Presentations” he asked, “What three or four points will your listeners find most helpful and persuasive?” (p. 335).

The other authors who discussed an overlap, however, included problematic statements. For example, Markel (2014) suggested that readers consider the purpose of the presentation and asked readers, “Are you attempting to inform or to both inform and persuade?” (p. 21). However, this implication—that presentations can only be informative—discourages readers from considering persuasive strategies, or even from being conscious of the possibility. Similar issues surfaced in Lannon and Gurak’s (2016) Technical Communication. The authors stated that if the reader’s “primary purpose” (p. 577) is to inform or persuade, then there are criteria for each in terms of what information to include. However, there was no explanation about the possibility of a combination of purposes and, instead, they suggested the reader select one.

Gerson and Gerson’s (2017) chapter contained more problematic explanations of purpose. They stated, “Almost every oral presentation has an element of argument/persuasion to it—as does all good written communication. You will usually be persuading your audience to do something based on the information you share with them in the presentation” (p. 513). However, in addition to stating that “almost every” presentation contains persuasion, they also divided presentation goals into inform, instruct, or persuade. The authors’ division raises the question of why these categories were included if, as they stated, persuasion is important in presentations. The distinction only makes determining a purpose more challenging, rather than more achievable.

The remaining three authors (Kolin, 2016; Oliu et al., 2016; Tebeaux & Dragga, 2018) discussed categories without specifying an overlap of informative and persuasive goals. Kolin (2016) stated, “Divide your presentation into major sections that best accomplish your objective, whether to inform, to persuade, or to document” (p. 636). Similarly, Oliu et al. (2016) suggested, “State and explain your key points—points that will inform or persuade your audience” (p. 492). With Tebeaux and Dragga’s (2018) oral report section, this delineation appeared in their discussion about organizational techniques: “This method will help your audience follow your ideas if you are giving an informative speech, an analytical speech, or a persuasive speech” (p. 301). These types of speeches—and how they are different or similar from one another— however, were not explained further.

Rhetorical Implications

Our analysis revealed many differing and contradicting ways informative and persuasive communication were handled in these textbooks. While some authors, such as Tebeaux and Dragga (2018) and Kolin (2016), emphasized persuasion in their general discussions, this emphasis became inconsistent when addressing oral presentations. Most authors excluded persuasion from report discussions; save for Tebeaux and Dragga (2018), Gerson and Gerson (2017), Anderson (2018), and, briefly, Pfeiffer and Adkins (2012) with progress reports; and only Markel (2014), Anderson (2018), and Johnson-Sheehan (2018) with scientific or empirical research reports.

We should note the possibility that the problematic logic and false dichotomy between informative and persuasive purposes may not be the product of firm ideologies or careful planning but of questionable conception and execution, which is ironic given that the subject of the textbooks is effective technical communication. That said, there is also an acknowledged gap between academy and industry, with academics and practitioners having divergent interests within the field (Boettger & Friess, 2016; St.Amant & Meloncon, 2016). However, to assume that the contradictions and problematic discussions within some of the textbooks are only because of differences between academics and practitioners would be an oversimplification. We do feel that the conflict between academy and industry is an important point to raise, however, because as Boettger and Friess (2016) discussed, it is important for practitioners to have a more active voice and role in the field’s scholarly production; the differences between what practitioners find relevant and what academics believe is relevant cannot be ignored.

Regardless of what caused the false dichotomies, the results of our analysis are significant for practitioners and students for several reasons. Johnson-Sheehan’s (2018) Technical Communication Today is the “body of knowledge” that candidates use for the Society of Technical Communication’s Foundation Certification, also referred to as the Certified Professional Technical Communicator (CPTC) designation. Our results indicate an issue for practitioners seeking this certification since Technical Communication Today contained the discourse divisions that are impractical for practitioners to be using; these divisions, however, are inescapable throughout the certification process because of the textbook’s material being the foundation for the study guide and exam. The CPTC Study Guide’s criteria for a successful candidate under the “Written Communication” category, for example, included the ability to “explain when and how to use plain and persuasive styles” (Society for Technical Communicators, 2016, p. 4). We must ask if these are the strategies that we want CPTC practitioners to be learning.

The textbook contradictions ultimately undermine the practitioner’s role. As Henning and Bemer (2016) stated, “Technical communicators do more than simply communicate; they employ particular modes of thinking to generate communication because they have common, specific goals” (p. 332). The many roles of technical communicators include deciding how to present ideas effectively to an audience and, to achieve this goal, technical communicators need to view discourse from a rhetorical, or persuasive, perspective. Ornatowski (1992) noted, “Technical writers are always inevitably rhetoricians precisely because they are ‘useful’ to employers and their writing is ‘effective’” (p. 100, emphasis in original). Because of this role, technical communicators must possess an awareness of their rhetorical purpose for composing, the wide variety of possible stakeholders in their audience, and the full range of argumentative choices available and their effects (Orantowski, 1995, p. 579).

The collaborative nature of the technical communicator’s role is also essential in creating effective deliverables (Hart & Conklin, 2006; Henning & Bemer, 2016; Rainey et al., 2005). Practitioners need to negotiate, problem-solve, and persuade to obtain the information they need from their colleagues and subject-matter experts, which is demonstrated in Brady (2007) and Wilson and Ford’s (2003) interviews with practitioners. This collaborative role, therefore, calls for a pedagogy that addresses rhetorical skills and knowledge of the subtle persuasive strategies evident not only in writing, but in communication holistically. The authors who categorized texts as either informative or persuasive focused on deliverables and written communication; likewise, many of the authors who acknowledged the importance of persuasion primarily did so with written communication (Gerson & Gerson, 2017; Kolin, 2016; Markel, 2018; Pfeiffer & Adkins, 2012; Riordan, 2013; Tebeaux & Dragga, 2018). Both groups neglected to discuss the rhetorical nature of interpersonal communication with colleagues, for example, which is an essential aspect of technical communication.

If students are led to believe that communication can be, as Pfeiffer and Adkins (2012) suggested, “neutral” and “objective,” or purely informational, then they are not prepared for the more complex aspects of rhetoric that are essential to effective communication. As others in the field have discussed (Dobrin, 1983; Miller, 1979; Ornatowski, 1992; Rutter, 1991), viewing forms of communication as objectively informative is not productive, useful, or desirable, save for those who would conceal persuasion’s presence. Furthermore, as Ornatowski (1992) argued, “If writing documents is only a matter of clearly marshalling objective facts and reasonable texts, ‘ethical’ problems should not arise. Something would either be a fact or not be a fact, be clearly relevant or be clearly irrelevant” (p. 99). Because of the complex intricacies of workplace communication, however, students and future practitioners must consider more than conveying information clearly, neutrally, and objectively for their purpose, whether the communication is an email to a colleague or a report to a manager.

Students must recognize these complexities to address what the communication needs to achieve; if scientific documents are perceived as only informing, then a critical purpose is ignored. As noted by Miller (1979), “Scientific observation relies on tacit conceptual theories, which may be said to ‘argue for’ a way of seeing the world. Scientific verification requires the persuasion of an audience that what has been ‘observed’ is replicable and relevant” (p. 616). Ultimately, even communication that seems informational needs to be considered on a persuasive level to create the desired impact on readers. Therefore, it is important to recognize that all writing operates persuasively in either implicit or explicit ways, and “all functional writing, including scientific and technical writing, is rhetorical: writers and readers together create meaning and knowledge through language” (Goldstein, 1984, p. 25). It is also important to recognize the need for consistently communicating purpose to technical communication students to assist them in their roles as effective practitioners.

The idea that all communication operates persuasively, and that no document or utterance just “informs,” may be difficult for students to reconcile in both an ethical sense and practical sense. Because technical communicators often encounter ethical dilemmas, the issue of ethics in technical communication has been heavily discussed (see Dombrowski, 2000), and undergraduate and graduate curricula often include chapters, modules, or entire courses in ethics for this reason (Malone, 2011). Despite this emphasis, the ethical dilemmas that technical communicators encounter at work are likely far more than they are prepared for through this curricula; as Dombrowski (2000) discussed regarding the shortcomings of ethical codes of conduct, ethical behavior “cannot be reduced to mechanical conformance to rules, because generalized rules cannot capture the complex contingency of real, particular situations, and because ethical conduct usually involves a heavy measure of personal judgment and decision making” (p. 4). While ethical conduct may be too difficult to capture in text, what we can do, however, is continue teaching students how to critically assess their communication decisions and teach them to be aware from the beginning that not only is all workplace writing rhetorical, but all general workplace communication is as well. Addressing this issue early will be to their advantage, as this guidance not only prepares them for considering the implications of their communication, but it also prepares them for the collaborative nature of their roles.

Instructors of technical communication have an ethical responsibility to represent the rhetorical complexities of real-world professional environments. To do otherwise is to actively mislead students and, in the process, fail to prepare them for what they will actually encounter in the workplace. As Brady (2007) stated, “What we teach matters” (p. 58). Understanding that all communication is rhetorical enables students’ interactions with the text to extend beyond just the information, to include moving the considerations toward whether the information is being effectively communicated to the text’s specific audience and “ultimately can inform their practice as they negotiate the fluid rhetorical contexts of the workplace” (Brady, 2007, p. 59).

Recommendations

Out of the textbooks examined, two stood out for avoiding many of the issues we have discussed. Tebeaux and Dragga (2018) excluded discourse categorizations in introductory discussions, instead emphasizing persuasion in reports and general writing. Anderson (2018) also communicated the importance of persuasion throughout general discussions, reports, and presentations. Therefore, these two hit closest to the mark if we had to suggest any of the books, though we will make clear that because Tebeaux and Dragga (2018) included discourse divisions in oral presentations, and because of Anderson’s (2018) unnecessary initial “useful” and “persuasive” divisions, the books are not exempt from our recommendations, which follow.

We propose:

- The distinction between “informative” and “persuasive” discourse should be eliminated. It may be useful to describe a text as “informative,” but only as a strategy of persuasion. Students do not need “informative” or “persuasive” categories to determine a rhetorical approach and accomplish their writing goals and, in any case, the division is false and misleading.

- Persuasion should be discussed with deliverables, written communication, and interpersonal communication between technical communicators, colleagues, and subject-matter experts. We noted a lack of discussion about persuasion with subject-matter experts in particular as we searched for discourse divisions.

- Both the subtle and overt persuasiveness of arguments that reports make should be discussed and analyzed. As the centerpiece of many technical writing courses with objective aims, reports are particularly susceptible to the “informative” label.

- Oral presentations should be linked to the discussions that occurred in other chapters about written texts. For example, if documents are characterized as always being persuasive, then given that oral presentations are based on similar guidelines to those of written documents, presentations merit the same treatment. The instruction presented for each of these forms of communication should be consistent.

We realize it is unrealistic to expect a quick, dramatic change in how this topic is discussed; however, we challenge those in the discipline to provide further clarity for technical communication students—and practitioners seeking certification—in their rhetorical roles. Stating a writer’s purpose is “to inform” is not specific enough to help the modern technical writer achieve his or her goal, “because it doesn’t take into account where the audience is starting from (with respect to the writer/speaker and the subject matter) and what the writer/speaker wants the audience to do with the information” (Keith, 1997, p. 307).

We believe students need more experience dealing with the thesis of “big rhetoric”—namely, that all communication, including their own writing and speech, no matter how neutral it may appear, has persuasive elements and intentions. By presenting some varieties of technical discourse as “informative,” we do them no favor but instead allow for rhetorical manipulation without awareness. The aim of the discipline is to both enable skill and promote understanding of that skill. Technical communication textbooks and curricula could present the relationship between rhetoric, writing, and speech in a more consistent manner that does not shrink away from the persuasive nature of all documents. Doing so will help in guiding our students toward becoming more effective and ethical technical communicators.

References

Anderson, P. (2018). Technical communication: A reader centered approach (9th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Bazerman, C. (1988). Shaping written knowledge: The genre and activity of the experimental article in science. University of Wisconsin Press.

Boettger, R. K., & Friess, E. (2016). Academics are from Mars, practitioners are from Venus: Analyzing content alignment within technical communication forums. Technical Communication, 63(4), 314–327.

Boettger, R. K., & Wulff, S. (2014). The naked truth about the naked this: Investigating grammatical prescriptivism in technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 23(2), 115–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2013.803919

Brady, A. (2007). What we teach and what they use: Teaching and learning scientific and technical communication programs and beyond. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 21(1), 37–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651906293529

Burke, K. (1969). A rhetoric of motives. University of California Press.

Cicero. (2001). On the ideal orator. (J. May & J. Wise, Trans.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published ca. 55 BCE)

Connors, R. (1981). The rise and fall of the modes of discourse. College Composition and Communication, 32(1), 444–455.

Dobrin, D. N. (1983). What’s technical about technical writing? In P. V. Anderson, R. J. Brockmann, & C. R. Miller (Eds.), New essays in technical and scientific communication: Research, theory, practice (pp. 227–250). Baywood Publishing Company.

Dombrowski, P. M. (2000). Ethics and technical communication: The past quarter century. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 30(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.2190/3YBY-TYNY-EQG8-N9FC

Freeman, R. (1973). Review [Review of the book A theory of discourse: The aims of discourse, by James L. Kinneavy]. College Composition and Communication, 24(2), 228–232. https://doi.org/10.2307/356519

Fulkerson, R. P. (1984). Kinneavy on referential and persuasive discourse: A critique. College Composition and Communication, 35(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/357679

Gerson, S. J., & Gerson, S. M. (2017). Technical communication: Process and product (9th ed.). Pearson.

Goldstein, J. R. (1984). Trends in teaching technical writing. Technical Communication, 31(4), 25–34. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43092097

Gross, A. (1988). The rhetoric of science. Harvard University Press.

Harned, J. (1985). The intellectual background of Alexander Bain’s “modes of discourse.” College Composition and Communication, 36(1), 42–50.

Hart, H., & Conklin, J. (2006). Toward a meaningful model for technical communication. Technical Communication, 53(4), 395–415. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43090790

Henning, T., & Bemer, A. (2016). Reconsidering power and legitimacy in technical communication: A case for enlarging the definition of technical communicator. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(3), 311–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616639484

Johnson-Sheehan, R. (2018). Technical communication today (6th ed.). Pearson.

Keith, W. (1997). Science and communication: Beyond form and content. In James H. Collier and David M. Toomey (Ed.), Scientific and technical communication: Theory, practice, and policy (pp. 299–326). Sage Publications.

Kinneavy, J. L. (1971). A theory of discourse: The aims of discourse. W.W. Norton & Company.

Knoblauch, C. H., & Brannon, L. (1984). Rhetorical traditions and the teaching of writing. Boynton/Cook.

Kolin, P. C. (2016). Successful writing at work (11th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Kuhn, T. (2012). The structure of scientific revolutions: 50th anniversary (4th ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Kynell, T. (1994). Considering our pedagogical past through textbooks: A conversation with John M. Lannon. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 24(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.2190/Y6V9-1WYH-6P70-LXX0

Lannon, J. M., & Gurak, L. J. (2016). Technical communication (14th ed.). Pearson.

Malone, E. A. (2011). The first wave (1953–1961) of the professionalization movement in technical communication. Technical Communication, 58(4), 285–306. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43092884

Manolescu, B. (2007). Religious reasons for Campbell’s view of emotional appeals in philosophy of rhetoric. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 37(2), 159–180.

Markel, M. (2014). Technical communication (11th ed.). Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Matveeva, N. (2007). The intercultural component in textbooks for teaching a service technical writing course. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 37(2), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.2190/85J8-2P74-1378-2188

McKerrow, R. (2015). “Research in rhetoric” revisited. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 101(1), 151–161.

Miller, C. (1979). A humanistic rationale for technical writing. College English, 40(6), 610–617. https://www.jstor.org/stable/375964

O’Banion, J. D. (1982). A theory of discourse: A retrospective [Review of the book A theory of discourse: The aims of discourse, by James L. Kinneavy] College Composition and Communication, 33(2), 196–201. https://www.jstor.org/stable/357627

Oliu, W. E., Brusaw, C. T., & Alred, G. J. (2016). Writing that works: Communicating effectively on the job (12th ed.). Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Ornatowski, C. M. (1992). Between efficiency and politics: Rhetoric and ethics in technical writing. Technical Communication Quarterly, 1(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 10572259209359493

Ornatowski, C. M. (1995). Educating technical communicators to make better decisions. Technical Communication, 42(4), 576–580. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43089802

Pfeiffer, W. S., & Adkins, K. E. (2012). Technical communication: A practical approach (8th ed.). Pearson.

Rainey, K. T., Turner, R. K., & Dayton, D. (2005). Do curricula correspond to managerial expectations? Core competences for technical communicators. Technical Communication, 52(3), 323–352. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43089277

Riordan, D. G. (2013). Technical report writing today (10th ed.). Wadsworth.

Rutter, R. (1991). History, rhetoric, and humanism: Toward a more comprehensive definition of technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 21(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.2190/7BBK-BJYK-AQGB-28GP

Schiappa, E. (2001). Second thoughts on the critiques of big rhetoric. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 34(3), 260–272.

Society for Technical Communication (2016, April). Certified Professional Technical Communicator (CPTC) study guide. https://www.stc.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/09/cptcstudyguide.pdf

St. Amant, K., & Meloncon, L. (2016). Reflections on research: Practitioner perspectives on the state of research in technical communication. Technical Communication, 63(4), 346–364.

Tebeaux, E., & Dragga, S. (2018). Essentials of technical communication (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Toulmin, S. (2003). The uses of argument. Cambridge University Press.

Walzer, A. E. (1991). The meanings of “purpose.” Rhetoric Review, 10(1), 118–129. https://www.jstor.org/stable/465520

Weaver, R. (1985). Language is sermonic: Richard M. Weaver on the nature of rhetoric. LSU Press.

Wilson, G., & Ford, J. D. (2003). The big chill: Seven technical communicators talk ten years after their master’s program. Technical Communication, 50(2), 145–159. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43089118

Wolfe, J. (2009). How technical communication textbooks fail engineering students. Technical Communication Quarterly, 18(4), 351–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572250903149662

About the Authors

Regan Joswiak is the assistant director of the Writing Center at the University of Houston-Clear Lake. Her research interests include rhetorical theory, academy and industry conflicts in technical communication, and writing program administration. She is available at joswiak@uhcl.edu.

Mike Duncan is an associate professor of English in the Technical Communication concentration at the University of Houston-Downtown. His scholarship ranges from rhetorical criticism and style to technical communication and early Christianity. His research has been published in College English, JAC, Rhetorical Society Quarterly, Rhetorica, Philosophy & Rhetoric, and Informal Logic, among others, and he has co-edited the collection The Centrality of Style. He can be reached at duncanm@uhd.edu.

Manuscript received 6 July 2018, revised 25 September 2018; accepted 21 November 2018.