by Julie Watts

ABSTRACT

Purpose: This study examines the value of requiring online master’s students in technical and professional communication (TPC) to design and conduct an independent research (IR) project as part of degree completion. Given that IR is a requirement in only a small percentage of TPC programs nationally, I wanted to discern IR’s value academically and in terms of applicable workplace skills, the benefits and challenges of conducting workplace-situated IR, and IR best practices.

Method: I conducted focus groups with faculty and surveyed alumni, students, and advisory board members to analyze IR perceptions.

Results: Respondents indicated that IR is an important intellectual outcome and desirable workplace skillset. Additional benefits include more ready engagement by students in workplace-situated IR and the potential to address workplace communication problems. Challenges involved gaining permission for a study, communicating IR recommendations to industry stakeholders via the academic thesis genre, and implementing workplace change based on IR results. IR best practices included embedding IR throughout coursework, providing sufficient resources, establishing a schedule, working with an advisor, and cultivating peer support.

Conclusion: IR’s academic and professional value needs to be better communicated to prospective and current students, faculty, and industry stakeholders. Students need guided opportunities to reflect on IR’s value to them as students and professionals, and they should have opportunities throughout coursework to identify an IR topic and build on it. More resources and opportunities for peer-to-peer IR support need to be developed as well as an alternate IR deliverable, more conducive to communicating research results to industry.

Keywords: research, technical and professional communication competencies, academia-industry divide, online teaching and learning

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- IR is a valuable academic and professional skill, helping technical communicators to practice identifying, researching, and solving communication problems and making them more marketable in the TPC industry.

- IR can investigate industry issues and help shape workplace communication.

- IR can connect academia and industry, providing student-professionals opportunities to use knowledge and skills from their courses and strategically apply these to investigate improvements to workplace communication practice.

- All stakeholders in the research process (students, faculty, employers) need support to best realize the benefits of research and its applications to industry’s communication issues and challenges.

The technical and professional communication (TPC) field has experienced an increase in degree and certificate programs, with baccalaureate, graduate programs, and professional development certificates more plentiful than ever (Melonçon, 2009; Melonçon, 2012; Melonçon & Henschel, 2013). Given this, programs must seek innovative ways to prepare technical communicators and to distinguish themselves from other credentialing opportunities (Johnson et al., 2018; Tillery & Nagelhout, 2015).

Our institution has offered an online master’s of science in TPC for 10 years, distinguished by what Lisa Melonçon (2009) calls a research-based “cumulative experience” (p. 141). A cumulative experience is a “thesis, project, portfolio, or practicum”—anything that “culminates the coursework of the graduate degree” (p. 141). Our program requires each student to work with an advisor to propose, design, and conduct independent research (IR), with the paper submitted to the Graduate School as a step toward degree completion. Few master’s programs require a similar experience: “68% of schools require a cumulative experience. Only 11% of schools require a traditional research based thesis, whereas most (70%) offer the thesis as an option” (p. 144). Our program’s IR often is workplace-situated, addressing or solving an organization’s communication issue. Because our university has promoted this for many years, the Graduate School includes this focus in its definition: “The paper . . . applies research methodology and principles relative to a particular discipline to solve a problem for a regional organization the results of which might apply only to the participating organization” (Research Guide).

I asked students, alumni, faculty, and advisory board members to analyze their perceptions about IR. This study’s impetus was three-fold. First, our students are working professionals, with the majority not planning to seek a doctoral degree. I wanted to investigate what benefits these students thought they gained from completing IR and whether they perceived these to be applicable in the workplace. Rachel Spilka (2009) argues that undergraduates who learn about research possess useful workplace skills. I wondered if student experiences completing IR during a master’s program translated similarly.

Second, our field encourages collaboration between academics and practitioners, especially conducting and disseminating research (Blakeslee, 2009; Spilka, 2000; see Technical Communication 2016, special issue on Improving Research Communication). One way of beneficially connecting these spheres is to collaborate on research that matters to both groups (Blakeslee & Spilka, 2004). Given this, I wondered how IR has been accepted into workplaces and whether project results have impacted workplace practices.

Third, I wanted to improve students’ experiences with IR. Of the students who completed IR, 40% have not finished within the semester timeframe identified as “standard” for its completion, suggesting that students’ preparation or their experiences could be improved. For many, completing IR increased their time-to-degree by at least one semester and has lengthened faculty advisement time accordingly. While degree completion issues are not uncommon (Denecke et al., 2009), one goal is to improve students’ experiences and to examine how IR is scaffolded in the program. In addition, scholarship recommending how to mentor students about research focuses mainly on doctoral students (Carpenter, 2015) and often does not attend to workplace-situated studies, which present unique challenges (Grant-Davie, 2005).

For my two-phase study, I answered these questions, conducting faculty focus groups and surveying alumni, students, and advisory board members to analyze IR perceptions. The results show the value and challenges of applying academic research to workplace problems, IR’s potential marketability, and how to foster connections between academia and industry.

- What value is IR to master’s students academically and in terms of applicable workplace skills?

- What are the benefits of conducting IR in the workplace? What are the challenges?

- What best practices do faculty, students, alumni, and advisory board members recommend for engaging in IR?

Literature Review

To situate these research questions and my study, I analyze how research is included in TPC curricula, the debate about the value of learning research, and how research may address TPC’s academia-workplace divide.

Research and Mentoring in Graduate Curricula

In her article advising prospective students about TPC graduate school, Angela Eaton (2009) writes that the inclusion of research as a program learning outcome differs between the master’s and doctorate: master’s programs “always prepare graduates to consume research and sometimes produce it,” while doctoral programs “always prepare [graduates] to produce it” (p. 150). This characterization is echoed in a curricular review of TPC master’s programs: nearly half of programs (48%) require a research methods course. However, only a small percentage of programs require students to conduct research as a cumulative experience (Melonçon, 2009).

Joyce Locke Carter (2013) describes how research is incorporated into the online Ph.D. program in technical communication and rhetoric at Texas Tech University. She writes that it includes a demanding expectation for research practice: “We have the most rigorous course requirements in research methods (4 courses) in the field of writing studies” (pp. 249–250). Students must attend an annual May Seminar, a two-week experience scheduled on campus. Students present their research, with faculty and peers “offer[ing] formative criticism designed to address performance, poster design, and engagement” (p. 263). Faculty share research in progress, “to model what we think scholarly inquiry looks like and to hopefully show our students what sharing formative ideas looks like” (p. 263).

Brent Henze (2006) analyzes a research-based internship designed for master’s students at East Carolina University. He believes that this internship benefits employers and students who work in industry (a population that does not benefit from the traditional internship model). In this “research-experiential internship” (p. 341), students locate a workplace problem that demands “advanced research in professional communication” (p. 342). The internship marries academic and industry work, by “tak[ing] advantage of the productive tension between the workplace goal (of solving the problem) and the academic goal (of using the problem as a learning opportunity)” (p. 344).

Another approach, also connecting academia with workplace contexts, is situated in an online graduate program. Keith Grant-Davie (2005) explains that the program’s internship was revised into “supervised workplace research projects” in which students were asked “to reflect on some of the practices in their workplace and to approach them with the critical eye of a researcher” (p. 221). Students were prompted to engage in “praxis . . . involv[ing] migrating frequently between application and reflection, between doing and pondering the ways things are done” (p. 222). A challenge of this approach was preparing students to conduct research. Using a committee structure (a chair and two faculty members) to advise each internship, Grant-Davie noted that teaching research methods appropriate for carrying out the project often fell to the chair: “Training individual students to conduct primary research was a very inefficient way to teach” (p. 227). Students’ lack of background in research methods and the demand on faculty time unfortunately led to the internship’s dissolution.

Formalizing into the curriculum these types of research opportunities is challenging but necessary. Jennifer Turns and Judith Ramey (2006) report on the University of Washington’s credit-based research groups, recommending that deliberate program integration is key to long-term success. These groups are vertically integrated, involving faculty, graduate students, undergraduates, and even community members. Participants may be involved from start to finish or they may assist with data analysis. The authors note that participants learn a great deal and cultivate disciplinary identity: “The opportunity to gain high-context insider knowledge associated with solving these problems (and subsequently to use that knowledge) . . . lead[s] to opportunities to feel more central to the research community, thus developing more of a researcher identity” (p. 304).

As these authors show, having students achieve research outcomes often involves more than simply enrolling students in courses: Students need to apply their skills and be mentored. Beverly Zimmerman and Danette Paul (2007) show that the TPC classroom is a valuable mentoring site. Mentoring complements the teaching relationship by “providing students with a role model or a sense of what they can become in the field . . . and developing a deeper and more ongoing supportive relationship with students” (p. 179). Mentoring programs are excellent ways for students to partner with professionals. The Society for Technical Communication (STC) coordinates the STC Mentor Board, pairing mentors with mentees, “foster[ing] personal and professional growth” (STC Mentor Board). While a TPC mentoring relationship takes on many forms (Eble, 2008), in the broader literature about research mentoring, best practice guides about dissertation advisement are most numerous (Carpenter, 2015).

Many of these offer advice for successful dissertation completion, including scheduling and developing a support network (Kochon, 2015) and identifying roles that faculty should adopt to help ensure student productivity. Serena Carpenter and her colleagues (2015) found that, besides the research role, faculty should adopt intellectual (research guidance), psychosocial (encouragement), and career roles. Vicente Lechuga (2011) also emphasizes that mentors help “develop graduate students’ sense of professional competence” (p. 766). Assisting students in this way means working to “operationalize equality” between faculty and student “by showing respect and mutual concern” (Miles & Burnett, 2008, p. 117).

One study examining the mentoring relationship between a faculty member and her undergraduate TPC researchers echoed these findings. Seven independent-study students collaborated on a project in which they applied research, presentation, and publication skills (Eaton et al., 2008). Students’ experiences participating in all stages of research was “an entirely new kind of learning” (p. 171). The project was successful because students were “research partners” and engaged in group decision-making (p. 160). Working with a mentor meant that research became “personalized”: “I let them see that I didn’t always know the answer, and that I often double-checked my initial inclinations using research texts” (p. 161).

Value of Research to Students and Professionals

Technical communicators are being hired into the “creative economy” in which problem-solving and research skills are critical (Bekins & Williams, 2006, p. 287). Many argue that a “greater variety of methods” should be present in program curricula (Rude, 2009, p. 177), and others lament that “research training” in TPC “is still uneven” (Blakeslee, 2009, p. 146), even though research methods is one of the “essential aspects of technical communication” (Melonçon & Henschel, 2013, p. 59).

Some suggest that research should be taught more frequently, but others believe its definition should be examined. Rachel Spilka (2009) maintains that undergraduates need to know more about research conducted in the workplace, which she calls “practitioner research,” which is “conducted by technical communicators as part of their routine or their specialized job responsibilities” (p. 217). Practitioner research is “local and limited, confined to the solution of internal problems” and with the potential to be “diverse . . . across types of contexts, [and] situations” (p. 217). Practitioner research often is not disseminated, making it “invisible to academics” (p. 224). Thus, research possesses flexible meanings and purposes relative to its context. Indeed, examining TPC studies analyzing which skills employers and alumni value suggests that to be true. Identifying skills valued by TPC professionals and managers is important for students and faculty to know (Kim & Tolley, 2004). Several studies indicate that research is not a skill used by TPC professionals. However, given the definition of practitioner research, this may not be the case; a handful of studies identify analysis or problem-solving skills that seem analogous to research.

Amy Whiteside (2003) surveyed and interviewed 24 TPC graduates from 10 undergraduate programs and 37 managers of technical communication units and conducted an analysis of schools’ programs to “suggest areas where technical communication students may need more preparation before entering business and industry” (p. 305). In this study, research as such is not mentioned. However, 57% of managers and 21% of recent graduates indicated that more preparation was needed in “problem solving skills” (p. 213). Whiteside notes that “problem-solving skills” help one “to understand how the product and device works in order to articulate its function to the user” (p. 314). This work involves research—analyzing existing documentation, interviewing subject matter experts, and/or testing the device.

Clinton Lanier (2009) examined skills listed in 327 technical writing job ads during a three-month period. While research was not one of the identified skills, 12% of the ads called for “analytic skills” (p. 58). This term, similar to problem-solving, is not defined by Lanier; however, he does classify it as a subcategory of project management. Wielding skills in analysis is one facet of successful research in that documents, data, situations, and/or users must be examined carefully as part of nearly any research process. Using Lanier’s study as a starting point, Rhonda Stanton’s (2017) survey of five recruiters and 60 job ads to determine what skills hiring managers look for in entry-level TPC employees found that “problem-solving skills” were “an important consideration when interviewing candidates” (p. 227). Likewise, “analytical skills” were included in nearly 25% of the 60 job ads examined (p. 231).

Greg Wilson and Julie Dyke Ford’s (2003) interviews with seven master’s program alumni revealed that participants needed more “practice obtaining difficult information” and “learned the hard way that information is not always readily handed over” (p. 157). While this skill may involve ascertaining how to access subject matter experts, it also suggests having strategies to seek data to complete tasks, a characteristic of practitioner research. James Dubinsky’s (2015) study involving eight TPC technology sector practitioners described how research was conducted—how “technical communicators gathered the data necessary to create usable products” (p. 125). The study showed that several “analytical approaches” were used—everything from “interviews with users or customers” to “focus groups” and “analysis of technical support or customer support data” (p. 125).

Literature suggests that the frequency of research differs by job or career sector. Eva Brumberger and Claire Lauer’s (2015) analysis of 914 TPC job postings during a two-month period indicated that research was relevant to each of the five job categories they analyzed: technical writer/editor, content developer/manager, grant/proposal writer, medical writer, and social media writer. However, the percentage in which research was mentioned as a competency differed by category, with research being most frequently cited in grant/proposal writer (62%), medical writer (50%), and technical writer/editor ads (40%), and less frequently mentioned in content developer/manager (28%) and social media writer (28%) (p. 236). Craig Baehr’s (2015) study also indicated differences in the frequency of research: “Research skills are acknowledged as important in user-centered content development, yet not considered to be absolutely essential to specific organizational roles” (p. 113).

Other studies note the presence of research but indicate its use is low (Hart & Conklin, 2006; Giamonna, 2004). Kenneth Rainey and his colleagues (2005) used surveys and interviews with 67 TPC managers to identify TPC competencies. Conducting research was identified as a “tertiary competency” along with usability testing, content management, budgeting, and awareness of cultural differences (p. 323). Similarly, Miles Kimball’s (2015) study ranked field research and usability research at the bottom of a list of TPC competencies: “This ranking reinforces evidence suggesting that usability testing and field research may be ideal skills, but not ones that practicing professionals have much time to apply” (p. 139).

Research and the Academia-Workplace Divide

In their study analyzing stakeholder theory and program administration, Jim Nugent and Laurence José (2015) confirm the presence of an academic-practitioner divide: “As a theoretical discipline rooted in workplace practice, technical communication finds itself circumscribed by a persistent dichotomy between academy and industry” (p. 11). Carolyn Rude (2015b) believes that cultivating shared goals between academia and industry strengthens our discipline but that “barriers” include perceptions about differing “values and cultures,” an inability to establish a “shared research focus,” and limited access to “meet in shared forums” (p. vi). Rude recommends establishing joint research questions: “Conversations about shared interests and needs should occur at the program level and beyond to determine foci for research” (p. vii).

Bridging this divide is important, in that mature disciplines rely on research to drive workplace practice, and this practice drives research (Spilka, 2000; Tebeaux, 1996). Research helps to build not only TPC’s identity but also individual professional identities (Rude, 2009; Rude, 2015a). Research strengthens our field, including scholarship about teaching and learning (Pope-Ruark, 2012) and studies in which academics and practitioners find value (St.Amant, 2015). Research collaboration enables academics and practitioners to “help one another professionally” and to achieve a “broader understanding about research across the greater field” (St.Amant & Melonçon, 2016, p. 346). Collaboration encourages everyone’s strengths, emphasizing that “[p]ractitioners do not belong to a simple homogenous category, and, of course, academics do not either” (Lauren & Pigg, 2016, p. 309).

Studies recommend strategies for using research to diminish this divide, noting that all research phases can be reevaluated. Gaining access to industry for research is challenging (Rude, 2009). However, when access is gained (Spinuzzi, 2010; Gollner et al., 2015), the benefits are clear. The workplace is only one type of site: other more novel environments for academic/practitioner collaboration include the classroom (Thrush, 2006) and electronic spaces such as the TCBOK, a technical communication body of knowledge wiki developed by a group from STC. The TCBOK, which assembles critical TPC knowledge, involves academics and practitioners (Coppola & Elliot, 2013).

Studies also recommend approaches for rethinking what questions to investigate. In studying TPC’s “core content” and its audiences, Ryan Boettger and Erin Friess (2016) argue for conducting research addressing industry issues: “Groups . . . (journal editors, bloggers, subsections of academics) must communicate, align and devise concrete solutions to real problems,” all the while “enable[ing] practitioner perspectives to influence our content more” (p. 324). Carolyn Rude (2015a) echoes this by noting that research should “facilitate industry practices” (p. 359) and researchers should “construct better, and more relevant, studies that could have potential generalizable application” (p. 357).

Toward this end, Joel Kline and Thomas Barker (2012) recommend a model for helping practitioners and academics to collaborate: a communities of practice CANFA model (collaborate, apply, facilitate, negotiate, and activate). They note that CANFA enables both groups to cultivate “one negotiated professional identity” since “professionalism rests on accepting and then transcending academic or practitioner identity” (p. 45).

Reaching academic and practitioner audiences is critical, and studies recommend dissemination approaches such as publishing research in venues other than academic journals (Boettger & Friess, 2016). In addition, research should be drafted with the “information-seeking needs of industry practitioners” in mind (St.Amant & Melonçon, 2016, p. 353), mimicking the “dissemination patterns that are used and valued by practitioners,” including concision and “report[ing] the most actionable and practical information” (Hannah & Lam, 2016, p. 340).

Solutions for completely ameliorating the academia-workplace divide have not been entirely successful; however, the argument for doing is strengthening. My study of the value of incorporating IR into a master’s program may provide another avenue for using academic research to help address industry problems and shape workplace communication trends.

Research Design

IR Program Requirement

Four of our 10 program learning outcomes concern research, and IR is a required step toward degree completion: Students must “have the primary responsibility for designing, conducting, and reporting the research,” understand and ethically apply “the basics of research design and data analysis,” and “effectively communicate ideas in writing” (“Research Expectations,” Research Guide). Students may fulfill their IR credit in one of two ways: ENGL-735 or ENGL-770. Three credits (ENGL-735) of the 30-credit degree can be IR; each student works with a faculty advisor to complete it. Students may enroll for 6 IR credits (ENGL-770), graduating with a 33-credit degree; in this case, the IR is advised by a three-member faculty committee. Students planning to pursue doctoral studies often enroll for 6 credits. The deliverable submitted to the Graduate School for ENGL-735 and ENGL-770 uses the same template, an academic thesis format. During the last five years, 17% of IR projects were 6 credits. In my analysis of the student and alumni surveys, I did not distinguish between respondents who enrolled for 3 or 6 IR credits.

Students are advised to complete IR during their final program semesters, and most enroll for IR during their final semester. Students work with the program director to identify a research topic and draft a prospectus, describing the research questions, methods, and a brief literature review (Appendix A). Students are encouraged to look to their workplaces for potential topics, although doing so is not a requirement. Once a prospectus is complete, students email their draft to a faculty member with whom they are interested in working. Once an advisor is identified, the student is enrolled into IR, which students have one year to complete.

In my program, IR has been formalized into the curriculum (Turns & Ramey, 2006). While IR is not an internship, it closely resembles the “research-experiential internship” described by Henze (2006), as projects often focus on investigating a workplace problem. While students learn about research methods in their courses, a responsibility for helping students to conduct research and write up their results falls to the advisor (Grant-Davie, 2005).

Methods and Participants

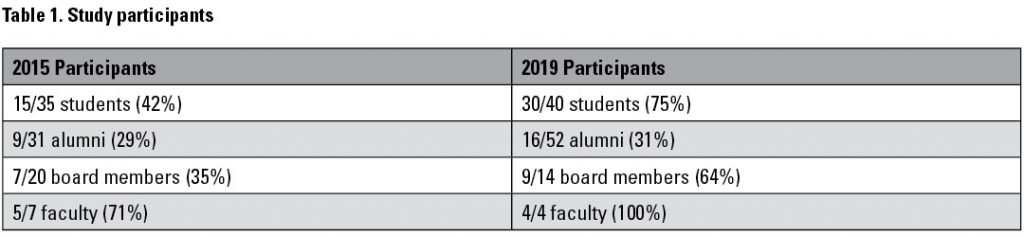

After Institutional Review Board approval, I conducted a two-phase study, collecting data in 2015 and in 2019. Table 1 shows the number of participants for each phase.

Student and alumni surveys

During 2015 and 2019, I distributed surveys to alumni (Appendix B) and students (Appendix C) to determine their IR satisfaction. During both phases, participants received individual email invitations via Qualtrics and surveys were available for five weeks.

Board member surveys and interviews

During 2015, I distributed a survey to all program advisory board members, which included faculty and employers, capturing their IR perceptions (Appendix D). Given the industry-focused nature of the study, I wanted to target industry voices for phase two. In 2019, I collected interview data from 14 of the 20 board members—only those employed in industry. To do so, I individually emailed each participant questions 2–5 from the 2015 board member survey. This standardized, open-ended interview strategy allowed me to ask the same questions to each participant and to use their time efficiently (Quinn Patton, 2015).

Faculty focus groups

During 2015, I invited program faculty with IR experience to a 1-hour focus group meant to capture advisor and student best practices (Appendix E). During 2019, additional faculty had IR advisement experience, and I invited them to a focus group, using the same questions and one-hour timeframe. Focus groups were preferable, allowing for “enhanced data quality” in that participants heard others’ responses and could contribute to the conversation (Patton, 2015, p. 478). I audiotaped the sessions and served as notetaker and facilitator. I transcribed the sessions, identifying relevant themes.

Results

IR Value Academically and Professionally

As program director, answering this question about IR’s value to students academically and professionally is critically important. Discerning what these stakeholders perceive about IR allows me to better engage in key conversations about program value. For example, when future industry partners ask me, “Why is IR worthwhile? Why should I potentially devote company resources toward supporting this?” I can tell them. Similarly, when prospective students or new graduate faculty ask me, “Given the time it takes to complete IR as well as the resources needed to support IR instructionally, why should this be a program requirement?” I can tell them. Most important, the responses demonstrate that IR is a common denominator in terms of value to both academia and industry. Thus, IR can assist in cultivating shared goals between these spheres, strengthening our discipline and helping to break down “barriers” about differing “values and cultures” (Rude, 2015b, p. vi).

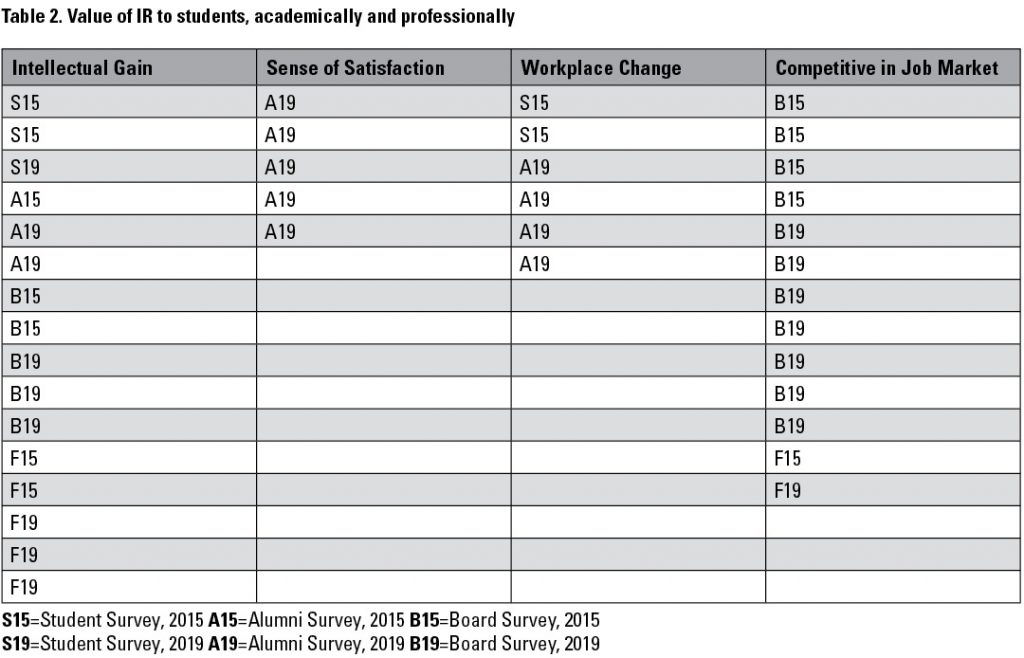

Table 2 summarizes the results of student, alumni, faculty, and board member perceptions about IR’s value, academically and professionally, identifying four major themes. While not all respondents used the surveys or focus groups to comment about IR’s value, those that did agreed that IR is an important academic skill to practice (Melonçon & Henschel, 2013) and one that benefits students professionally (Spilka, 2009). The intellectual gain of completing IR was valuable, and this was the only theme that members of all groups mentioned. Alumni indicated that a value of IR was a sense of satisfaction about its completion, and primarily board members but faculty as well indicated that IR made students more competitive in the job market. Students and alumni noted IR’s value for workplace change.

The intellectual gain noted by study respondents characterized IR as a stimulating, expected part of master’s degree work. As one former student noted, “The whole process challenged me, and as a result, I improved my writing and learned much about conducting research” (Alumni Survey, 2015). With a board member concurring, “The IR could also be a great place to stretch, intellectually, a good bit” (Board Survey, 2015). Faculty agreed that earning a master’s degree equated to IR skills proficiency: “Because if you don’t come out of a master’s program without being able to conduct IR, what are we doing?” (Faculty Focus Group, 2019). The IR is a true “cumulative experience;” as one board member noted, “I’m assuming the IR gives the student an opportunity to pull together all of their program learning, to date—a capstone of sorts. That type of exercise is invaluable for solidifying student learning” (Board Survey, 2019).

Some respondents also perceived that IR’s value lay beyond its worth as a programmatically situated set of skills: “Research is the life skill, the professional skill where the real value lies” (Faculty Focus Group, 2015). One board member discussed IR’s value in elevating academic learning and to students’ industry success:

Students spend a majority of their academic career responding to questions, prompts, and problems that have been pre-figured for them to achieve specific learning outcomes, and an IR project removes those guardrails, requiring that they fashion their own questions, methods, data collection, analysis, and reporting. Moreover, to be successful, they need to do this while seeking out and responding to feedback from mentors and stakeholders. This sort of work more closely matches the level of ownership they’ll need to have in their professional lives to be successful. (Advisory Board Survey, 2019)

Alumni respondents seemed to concur with this, noting the satisfaction of IR completion, “I never thought I could tackle a project as extensive as IR but so happy I did and to this day remains as one of my most significant accomplishments” (Alumni Survey, 2019).

Respondents, particularly board members, perceived that the possession of IR skills made students more marketable. Respondents noted that IR distinguishes students employed in their current role: student-employees “go above and beyond their colleagues by showing initiative, brighter ideas, and a higher ability to spearhead projects independently or in a team setting” (Board Survey, 2019). Possessing IR skills helps with employee review: “Research skills are invaluable when evaluating job candidates as research often builds strong critical thinking skills, ability to analyze large data sets into key take-aways, ability to translate numbers into writing, etc.” (Board Survey, 2019). Students are competitive for new positions: “I view the capstone project as a positive approach and potentially a differentiator for the program. As a hiring manager, an applicant with applied experience is significantly more valuable than one with the credential, only” (Board Survey, 2015).

Some student and alumni respondents indicated that IR’s value meant facilitating change in their workplace. Some indicated that change occurred: “The results of my research have been well-implemented at my current organization and have positively impacted public-facing communication” (Alumni Survey, 2019). While others pointed to its potential: “It started a discussion about an issue that my coworkers weren’t aware of” (Alumni Survey, 2019) or “Hopefully it will bring problems to light and create change to resolve them” (Student Survey, 2015).

Benefits and Challenges of Workplace-situated IR

An obvious benefit of workplace-situated IR, as evidenced by the discussion above, is the value it brings to students. However, faculty and board members noted other benefits. Faculty discussed the exigence that workplace-situated IR brings to a project: “There’s automatic engagement. Essentially [students] have an audience. They are doing this for their employer or for what they’re doing on a day-to-day basis” (Faculty Focus Group, 2015). Faculty noted that a workplace context often facilitated research:

It’s a problem that they are trying to tackle not just to check a box or to get a piece of paper, it’s their job. . . . That reality impacts the work because the contexts are right in front of them. So that in some ways makes doing the research easier. (Faculty Focus Group, 2019)

Board members cited other benefits of IR, including happier employees (“allowing employees to explore their curiosities and passions, which ideally pursues retention long term”) and improving the company’s bottom line (“it’s also cheaper than hiring a contractor to do the work”) (Advisory Board Surveys, 2019).

Much like student and alumni perceptions about IR’s value to workplace change, board members and faculty also articulated this as a benefit. Several board members noted IR’s potential to impact decision making in several ways: “using data to drive decisions;” IR “would allow for an in-depth look at a particular duty or aspect of a job that otherwise may be overlooked;” and an “opportunity to examine an issue using the latest theories, approaches and potentially some different tools” (Advisory Board Surveys, 2019). Faculty also noted the enthusiasm students have for workplace-situated IR: “His project applies to his job so there’s this extra thing that he really wants to know and really to take back” (Faculty Focus Group, 2015).

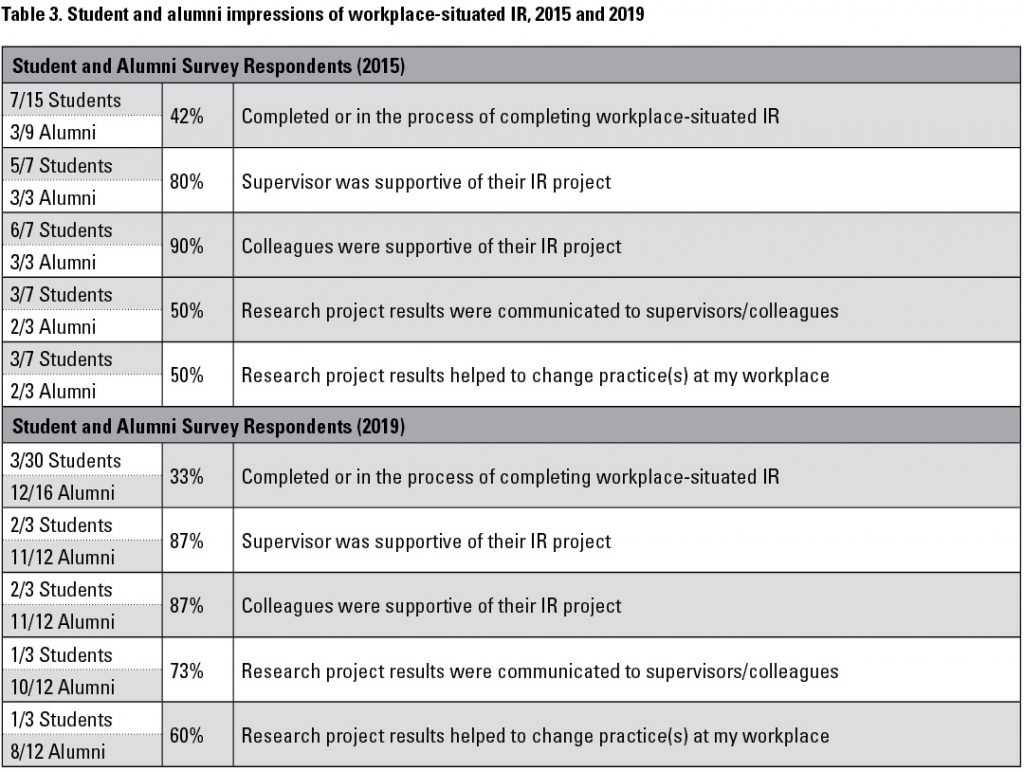

Table 3 shows the percentage of student and alumni respondents in 2015 and 2019 who completed or were in the process of completing workplace-situated IR as well as the levels of support they received. Table 3 shows whether IR results were communicated to stakeholders and notes their impact on altering workplace practice. The fairly high percentages of supervisor and colleague support are not surprising, as students who propose IR generally do so within their companies and need to have approval and often colleague support. In 2015, 50% of respondents indicated that their IR “helped to change practice(s) at my workplace,” while this percentage increased to 60% in 2019.

Enacting such workplace change can be challenging, however, and students and board members discuss why. IR often does not point to recommendations: “My results were very mixed, which made it difficult to suggest any concrete changes to the communication process I studied” (Student Survey, 2015). Sometimes, the results do recommend action but the organization is challenged to implement it: “If processes have been in place for several years, it can be difficult to convince others to try something new” (Advisory Board Survey, 2015).

Respondents also noted the difficulty of simply launching workplace-situated IR. Employer reluctance, access to data, employee/colleague collaboration, and timing were just some of the challenges: “Supervisors and the IR department are concerned of anything that might not show my employer in a favorable light. As soon as they found out my paper would be published they forbid a survey and use of non-public data” (Student Survey, 2015). Often, IR data are proprietary: “Legal departments almost always need to get involved to determine issues of confidentiality of information” (Advisory Board Survey, 2015) and “privacy issues and data security/protection regulations are increasingly strict” (Advisory Board Survey, 2019). Involving colleagues can be difficult: “Employers are busy and it’s hard to fit more meetings into their schedule” (Advisory Board Survey, 2015). When an industry project needs to be launched immediately, phases of research may not coordinate: “Viability would be hindered by the lead time that it takes to gain IRB [institutional review board] or similar approval” (Advisory Board Survey, 2015). Supervisors also may be uneasy about incorporating IR into existing duties: “how the research would insert itself into [employees’] workflow and how much time it would take up” (Advisory Board Survey Survey, 2019).

Faculty also noted that workplace-situated IR may possess different challenges than other IR. Notably, students can become overanxious to address their workplace singularly: The IR topic “can be too narrow at times. I [as faculty advisor] need to bring it out a little bit and to think more broadly about it . . . to also show how it would be relevant to other industries” (Faculty Focus Group, 2015). Students can be reluctant to situate the issue within TPC literature: “The con there too is . . . not wanting to find the literature because they’re so into solving the problem” (Faculty Focus Group, 2015). Likewise, students may be hesitant to examine the topic using a theoretical lens, saying, “If it’s a workplace piece . . . then why do I need all of this theory to inform it?” (Faculty Focus Group, 2019).

While the IR deliverable prompts students to comprehensively situate their project and argue for their results, faculty noted that the deliverable, a templated academic genre required by our institution’s Graduate School, was not the most effective for students to practice and limited their ability to communicate IR recommendations to workplace stakeholders and supervisors: “They need to conduct the research, they need to frame the study, they need to be able to understand it, but the writing up of that, sometimes I struggle if we need that” (Faculty Focus Group, 2019). Many institutions are moving away from a traditional thesis or dissertation format (Robinson & Dracup, 2008; Thomas et al., 2016), and some faculty expressed that they would like more choices: “This field work is not like an academic thesis, this is a different beast. There needs to be more flexibility” (Faculty Focus Group, 2015).

Faculty noted that this academic format often stymied students’ ability to communicate their IR recommendations to industry. One faculty member explained:

I feel like she [a previous advisee] should have been able to take that lesson she learned from her research and bring it back to her company . . . but there is no way that will happen if she said, ‘Well, you should read my paper.’ . . . But being able to design a project, do the research and then defend your arguments enhances [students’] ability to be able to become thought leaders in their industry. (Faculty Focus Group, 2019)

One former student echoed this sentiment, “I never really understood the purpose of all the formatting conventions of academic papers. . . . I was kind of embarrassed to send the full paper to colleagues because of this. . . . I think it would be ideal if the deliverable was something more fitting for a business environment” (Alumni Survey, 2019).

Faculty discussed the possibility of using other “not scholarly” deliverable forms to communicate IR results (Faculty Focus Group, 2015). They discussed the feasibility of requiring a presentation and/or slide deck where students would be asked to “talk about [the research] in intelligent ways,” noting that an “oral defense” would better mimic what students would “do when you go out and stand in your board room, when people are saying, ‘Why should we invest in X?’ Well because” (Faculty Focus Group, 2019).

Faculty and students also commented on their confusion concerning the difference between ENGL-735 (3-credit IR) and ENGL-770 (6-credit IR). Like several programs at our institution, either course fulfills students’ IR requirement, and the Graduate School does not distinguish clearly between the two. Moreover, the deliverable for both is the same (the academic thesis). In general, I advise those students who plan to pursue doctoral work toward the 6-credit option. However, a clearer distinction between the two options seems needed: “I think it should be a little clearer about the differing goals of the 735 vs. 770. . . . It’s hard to say exactly why the goals became less distinct as I started the project, but I remember at the time thinking that myself and my adviser had slightly different understandings about the two options” (Alumni Survey, 2019). As faculty advisors commented, “The main components of both [options] are very similar. . . . The basics are the same” (Faculty Focus Group, 2015) and “The thing that would help me . . . is having a clearer sense of the objectives of the IR requirement, and then if those are differentiated between the 735 and 770 paper” (Faculty Focus Group, 2019).

IR Best Practices

Because IR is an individualized pedagogical activity, I wanted to hear what participants thought worked and what needed work in terms of IR preparation and practice. While conclusions regarding the IR deliverable and IR course options will be examined in the subsequent section, several recommendations regarding curriculum integration, resources, and advisor and peer roles are discussed below.

Deliberate curriculum integration

I advise our students to identify IR as a concluding element in their degree, with most enrolling for IR during their final semester. Respondents indicated that students should discern IR topics earlier, with IR better integrated throughout the program: “Begin the discussion of the thesis in the very first class and carry it through so that students do not wait until they are done with their classes to begin thinking about what they would like to write about” (Alumni Survey, 2015). A student recommended, “Start the research paper in a required introductory course within the first nine (9) credits, preferably taught by the Program Director. . . . Setting it up early means students can incorporate what they learn in subsequent courses” (Student Survey, 2015).

Resources and models

In 2015, 61% percent of alumni respondents stated that the IR information on the program website helped to “prepare them to engage in IR”; in 2019, this percentage increased to 68%. While students are using Web resources, more information is needed. Students were challenged to develop their IR topics, so more resources could be devoted to this: “Actually coming up with the idea and the proposal was very difficult. I would have loved a lot more guidance on that process” (Alumni Survey, 2019). Respondents wanted more detail describing “how to find a chair, write the proposal” and so forth (Alumni Student Survey, 2015). Faculty also wanted a “clearly defined guide” stipulating the “skills students should need” coming into IR, using language from the program outcomes, so faculty and students would better understand what preparation students need before embarking on IR (Faculty Focus Group, 2019).

Advisor role

Respondents agreed the faculty advisor was key in IR success: “Personally, I need my advisor to help keep me grounded and set a reasonable scope” (Student Survey, 2019). One student indicated the advisor should be selected earlier: “I think students would have to pick an advisor before 50% completion of degree. That way the advisor and student can establish communication, set up the goals, proposed timeline, hone the topic etc.” (Student Survey, 2015). Advisor availability also was important: “My advisor was very dedicated to guiding me through the research process” (Alumni Survey, 2015). As one student noted, “I never felt as though I was alone in my work and could always reach out to the program director or advisor” (Alumni Survey, 2019). Providing “timely feedback” was critical (Alumni Survey, 2019)—as one faculty member stated: “I try to be quick in terms of reviewing their drafts. I ask students to tell me what specifically they want me to look at” (Faculty Focus Group, 2015).

Schedules and contact

Students establish an IR timeline in their prospectus, and this was important to success: “Set up a timeline and stick to it. It’s easy to fall behind without hard deadlines” (Alumni Student Survey, 2015). Several students spoke to this by noting IR’s time-consuming nature: “Give yourself lots of time to complete the project and do lots of prep work. Everything seems to take longer than you think it will” (Alumni Survey, 2019). Several alumni recommended students select topics they were “passionate” about: “This project takes up so much of your time and life that you don’t want to be consumed with a topic that you’re only ‘somewhat’ interested in” (Alumni Survey, 2019). Faculty also noted the importance of consistent contact: “[Weekly meetings] gives them some accountability, and even if there is really very little to report at least you do check in” (Faculty Focus Group, 2015).

Peer support

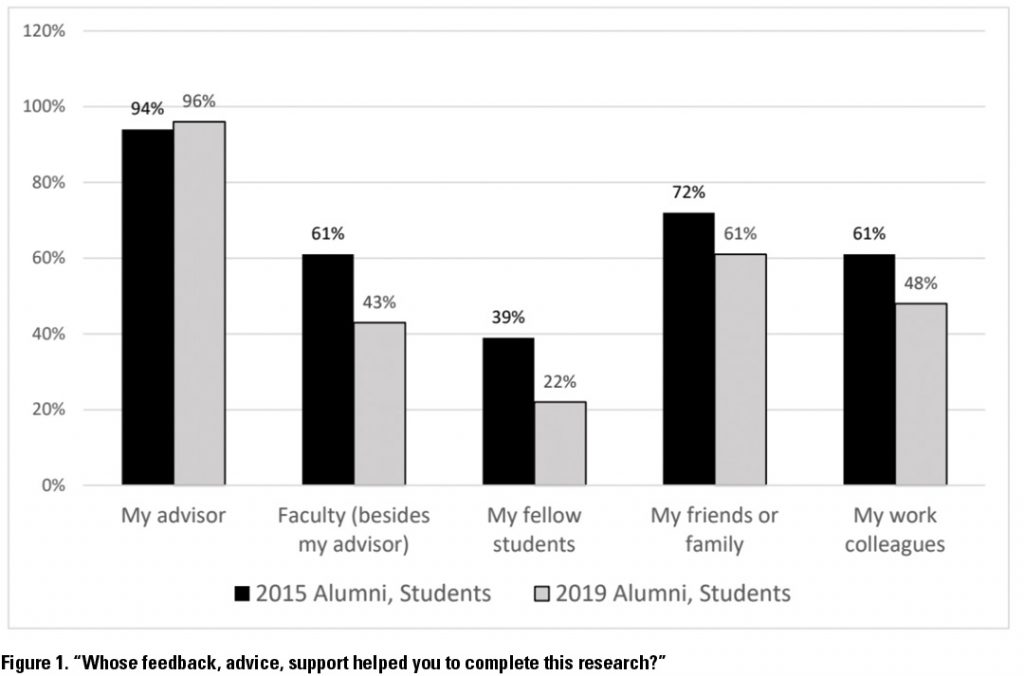

Figure 1 shows how students and alumni who completed IR responded to the question, “Whose feedback, advice, support helped you to complete this research?” The most critical support systems included the advisor as well as friends/family. The lowest rated category was “my fellow students.” This lack of peer-to-peer support also appeared in other responses: “As an online student I suspect I missed out on a lot of the support, discussion, and personal anecdotes about the research process that were available to students who were closer to campus” (Alumni Survey, 2015). Another student noted that technology could have assisted: “As a distance learner, I didn’t have a cohort of other students to get together with for ideas or help. But that could definitely be done remotely/virtually” (Alumni Survey, 2019).

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study demonstrated that IR is valuable to TPC master’s students academically and in terms of applicable workplace skills. Unfortunately, students do not seem to realize how competitive IR makes them (Table 2). Given that only 11% of master’s programs require IR as a cumulative experience, my program needs to do a better job of communicating this value to students and prospective students. This information needs to be integrated into existing marketing materials, including the program’s website, its print and video promotional materials, and in its prospective student communication. A synopsis of the study results can be integrated into these materials along with survey and focus group quotes. Expertise from the advisory board also should be tapped to learn how they believe IR’s value should be communicated.

Students should be prompted to reflect on what IR has taught them academically and professionally. Once students have completed IR, they have no guided opportunity to reflect on this, even though reflection is highly beneficial (Westberg & Jason, 2001). Our program requires incoming students to complete a course-embedded online student orientation to help familiarize them with the skills and behaviors they should possess to succeed online (Watts, 2019). A second online orientation of sorts may be needed before students exit the program: one used to help students analyze their learning and its benefits. This online experience could be modular and self-paced, and students could reflect on their courses, IR, and how these experiences helped them to achieve the program’s learning outcomes and what this achievement says about them as TPC professionals. These results could be used in place of an exit interview and could complement existing program assessment and alumni surveys.

Several advising changes will be made to help improve students’ IR preparation. Initially IR was conceived of as an experience completed near the program’s end. Instead, students will be advised to identify an IR topic earlier and seek ways to build on that topic through coursework. A required course taken early in their program familiarizes students with TPC theory and research, and this course will now introduce students to the IR process and use IR as a lens with which to discuss and apply research. Students also will be encouraged to extend the length of their IR registration from a single semester to 2 or 3, which will give students more time to read, write, and think about their topic.

Results indicate that students rely on friends and family for support during IR but do not rely on their fellow students (Figure 1). Students do not have opportunities to connect with one another outside of courses. To address this, I am working with our institution’s social media coordinator to launch a campaign using Facebook Groups to provide an alternate channel of communication for students, which also will invite prospective students, alumni, faculty, and board members. The Group could serve as a springboard for students to connect about IR questions and concerns, and for alumni, faculty, and board members to share their ideas.

Relying on existing program and Graduate School Web resources as well as an outdated program manual is not providing students, faculty, and industry partners the information they need to prepare for and engage in IR. Students and faculty need a pre-IR guide, linked to existing program outcomes, communicating clear expectations for student IR preparedness. The program outcomes concerning research should be invoked, as should the courses where such outcomes are practiced. The guide should include expectations for the program director and advisor roles in IR, describing best practices for students and faculty. Inviting industry partners to complete a survey before, during, or after the IR project situated in their workplace is near completion could provide a wealth of information not only about best practices for timing and integrating research into the workplace but also how to impact workplace practice. Our institution’s Career Services office engages similarly with industry when coordinating students’ cooperative education, and their resources could be used as models. Providing feedback opportunities and extending resources to industry cultivates more substantive partnerships, helping to populate our board, recruit, and further improve IR. Achieving this level of communication with industry could go a long way toward breaking down the academia-workplace divide.

Study participants want to see more distinction between the 3-credit and 6-credit IR course options as well as an alternate deliverable in lieu of the traditional academic thesis. The 6-credit IR course option could retain the academic thesis format, while the 3-credit option could include an alternate deliverable, one more conducive to communicating research results to industry. Doing so would enable students who engage in workplace-situated IR to more effectively communicate their results and recommendations to stakeholders. Programs are moving away from traditional thesis and dissertation formats to better “prepare scholars for future professional pursuits” (Thomas, 2016, p. 82), noting that writing in traditional formats is “different from the process of completing research post-graduation” (p. 83). Concerns with alternate formats involve ensuring that students have adequate opportunities for engaging in “writing to learn” about the IR process, including posing research questions, situating the study in the research, and describing how methods were deployed (Faculty Focus Group, 2019).

The impetus for this study was three-fold: to investigate the benefits of IR to students academically and professionally, to identify how IR might encourage collaboration between academics and practitioners, and to improve students’ IR experiences. The study shows that stakeholders perceive IR’s value as an important intellectual outcome and desirable workplace skillset. Given this, the program aims to better showcase this value and work to sustain and improve it.

IR provides opportunities to promote productive connections between academia and industry. Moreover, communication challenges that stymie workplace efficiency, accuracy, or productivity can find an audience with IR. Student-professionals, intimately knowledgeable about a workplace context and its communication challenges, are uniquely poised to collaborate with faculty and colleagues to help address or even ameliorate these challenges. Moreover, IR investigations promote an awareness of industry—its problems, values, contexts, practices, and so on—often not afforded to academics. The program aims to better facilitate this relationship—more satisfactorily preparing faculty and students for IR while listening and responding to industry feedback about strategies to integrate IR and implement any relevant recommendations.

The study shows specific ways not only to improve students’ experiences with IR but also to improve the experiences of faculty and industry partners. More deliberate curricular scaffolding, additional resources, a formalized feedback loop from the program to the workplace and back, and alternate IR deliverable options are some of the strategies to be implemented. By instituting changes like these, IR will become a lynchpin, connecting academia and industry, providing student-professionals opportunities to use knowledge and skills learned from their courses and strategically apply these to investigate improvements to workplace communication practice.

References

Baehr, C. (2015). Complexities of hybridization: Professional identities and relationships in technical communication. Technical Communication, 62(2), 104–117.

Bekins, L. K., & Williams, S. D. (2006). Positioning technical communication for the creative economy. Technical Communication, 53(3), 287–295.

Blakeslee, A. M., & Spilka, R. (2004). The state of research in technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 13(1), 73–92.

Blakeslee, A. M. (2009). The technical communication research landscape. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 23(2), 129–173.

Boettger, R. K., & Friess, E. (2016). Academics are from Mars, practitioners are from Venus: Analyzing content alignment within technical communication forums. Technical Communication, 63(4), 314–327.

Brumberger, E., & Lauer, C. (2015). The evolution of technical communication: An analysis of industry job postings. Technical Communication, 62(4), 224–243.

Career Services, Co-op Information. University of Wisconsin-Stout, https://www.uwstout.edu/academics/career-services/cooperative-education-program.

Carpenter, S., Makhadmeh, N., & Thornton, L.-J. (2015). Mentorship on the doctoral level: An examination of communication faculty mentors’ traits and functions. Communication Education, 1–19.

Coppola, N. W., & Elliot, N. (2013). Conceptualizing the technical communication body of knowledge: Context, metaphor, and direction. Technical Communication, 60(4), 267–278.

Denecke, D., Frasier, H., & Redd, K. (2009). The Council of Graduate Schools’ PhD completion project. In R. G. Ehrenberg and C.V. Kuh (Eds.), Doctoral education and the faculty of the future (pp. 35–52). Cornell University Press.

Dubinsky, J. M. (2015). Products and processes: Transition from ‘product documentation to … integrated technical content.’ Technical Communication, 62(2), 118–134.

Eble, M. F., & Gaillet, L. L. (2008). Stories of mentoring: Theory and praxis. Parlor Press. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uws-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3440416

Eaton, A., Rothman, L., Smith, J., Woody, R., Warren, C., Moore, J., Strosser, B., & Spinks, R. (2008). Mentoring undergraduates in the research process: Perspectives from the mentor and mentees. In M. F. Eble and L. L. Gaillet (Eds.), Stories of mentoring: Theory and praxis. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uws-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3440416

Eaton, A. (2009). Applying to graduate school in technical communication. Technical Communication, 56(2), 149–171.

Giamonna, B. (2004). The future of technical communication: How innovation, technology and information management and other forces are shaping the future of the profession. Technical Communication, 51(3), 349–366.

Gollner, J., Andersen, R., Gollner, K., & Webster, T. (2015). A study of the usefulness of deploying a questionnaire to identify cultural dynamics potentially affecting a content-management project. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 53(3), 289–308.

Grant-Davie, K. (2005). An assignment too far: Reflecting critically on internships in an online master’s program. In K. Cargile Cook and K. Grant-Davie (Eds.), Online education: Global questions, local answers (pp. 219–227). Routledge.

Hannah, M. A., & Lam, C. (2016). Patterns of dissemination: Examining and documenting practitioner knowledge sharing practices on blogs. Technical Communication, 63(4), 328–345.

Hart, H., & Conklin, J. (2006). Toward a meaningful model for technical communication. Technical Communication, 53(4), 395–415.

Henze B. R. (2006). The research-experiential internship in professional communication. Technical Communication, 53(3), 339–347.

Johnson, M. A., Simmons, W. M., & Sullivan, P. (2018). Lean technical communication: Toward sustainable program innovation. Routledge.

Kim, L., & Tolley, C. (2004). Fitting academic programs to workplace marketability: Career pathos of five technical communicators. Technical Communication, 51(3), 376–386.

Kimball, M. A. (2015). Training and education: Technical communication managers speak out. Technical Communication, 62(2), 135–145.

Kline, J., & Barker, T. (2012). Negotiating professional consciousness in technical communication: A community of practice approach. Technical Communication, 59(1), 32–48.

Kochon, F. (2015). Strategies for dissertation writing success. In R. L. Calabrese and P. Smith (Eds.), The faculty mentor’s wisdom: Conceptualizing, writing, and defending the dissertation (pp. 27–34). Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Lanier, C. R. (2009). Analysis of the skills called for by technical communication employers in recruitment postings. Technical Communication, 56(1), 51–61.

Lauren, B., & Pigg, S. (2016). Toward multidirectional knowledge flows: Lessons from research and publication practices of technical communication entrepreneurs. Technical Communication, 63(4), 299–313.

Lechuga, V. M. (2011). Faculty-graduate student mentoring relationships: Mentors’ perceived roles and responsibilities. Higher Education, 62(6), 757–771.

Locke Carter, J. (2013). Texas Tech University’s online PhD in technical communication and rhetoric. Programmatic Perspectives, 5(2), 243–268.

Melonçon, L. (2009). Master’s programs in technical communication: A current overview. Technical Communication, 56(2), 137–148.

Melonçon, L. (2012). Current overview of academic certificates in technical and professional communication in the United States. Technical Communication, 59(3), 207–222.

Melonçon, L., & Henschel, S. (2013). Current state of U.S. undergraduate degree programs in technical and professional communication. Technical Communication, 60(1), 45–64.

Miles, K. S., & Burnett, R. E. (2008). The minutia of mentorships: Reflections about professional development. In M. F. Eble and L. L. Gaillet (Eds.), Stories of mentoring: Theory and praxis. Parlor Press.

Nugent, J., & José, L. (2015). Stakeholder theory and technical communication academic programs. In T. Bridgeford and K. St.Amant (Eds.), Academy-industry relationships and partnerships: Perspectives for technical communicators (pp. 11–30). Baywood Publishing.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed). SAGE Publications.

Pope-Ruark, R. (2012). Back to our roots: An invitation to strengthen disciplinary arguments via the scholarship of teaching and learning. Business Communication Quarterly, 75(4), 357–376.

Rainey, K. T., Turner, R. K., & Dayton, D. (2005). Do curricula correspond to managerial expectations? Core competencies for technical communicators. Technical Communication, 52(3), 323–352.

Research Guide, University of Wisconsin-Stout. https://www.uwstout.edu/academics/colleges-schools/graduate-school

Robinson, S., & Dracup, K. (2008). Innovative options for the doctoral dissertation in nursing. Nursing Outlook, 58, 174–178.

Rude, C. D. (2009). Mapping the research questions in technical communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 23(2), 174–215.

Rude, C. (2015a). Building identity and community through research. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 54(4), 366–380.

Rude, C. (2015b). Foreword: Considering partnerships and relationships in the field. In T. Bridgeford and K. St.Amant (Eds.), Academy-industry relationships and partnerships: Perspectives for technical communicators (pp. v–ix). Baywood Publishing.

Spilka, R. (2000). The issue of quality in professional documentation: How can academia make more of a difference? Technical Communication Quarterly, 9(2), 207–220.

Spilka, R. (2009). Practitioner research instruction: A neglected curricular area in technical communication undergraduate programs. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 23(2), 216–237.

Spinuzzi, C. (2010). Secret sauce and snake oil: Writing monthly reports in a highly contingent environment. Written Communication, 27(4), 363–409.

Stanton, R. (2017). Do technical/professional writing (TPW) programs offer what students need for their start in the workplace? A comparison of requirements in program curricula and job ads in industry. Technical Communication, 64(3), 223–236.

St.Amant, K. (2015). Introduction: Rethinking the nature of academy-industry partnerships and relationships. In T. Bridgeford and K. St.Amant (Eds.), Academy-industry relationships and partnerships: Perspectives for technical communicators (pp. 1–8). Baywood Publishing.

St.Amant, K., & Melonçon, L. (2016). Reflections on research: Examining practitioner perspectives on the state of research in technical communication. Technical Communication, 63(4), 346–364.

STC Mentor Board. Society for Technical Communication. https://www.stc.org/mentor-board/

Tebeaux, E. (1996) Nonacademic writing into the 21st century: Achieving and sustaining relevance in research and curricula. In A. H. Duin and C. J. Hansen (Eds.), Nonacademic writing: Social theory and technology (pp. 35–55).

Thomas, R. A., West, R. E., & Rich, P. (2016). Benefits, challenges, and perceptions of the multiple article dissertation format in instructional technology. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 32(2), 82–98.

Thrush, E. A., & Hooper, L. (2006). Industry and the academy: How team-teaching brings two worlds together. Technical Communication, 53(3), 308–316.

Tillery, D., & Nagelhout, E. (2015). The new normal: Pressures on technical communication programs in the age of austerity. Baywood.

Turns, J., & Ramey, J. (2006). Active and collaborative learning in the practice of research: Credit-based directed research groups. Technical Communication, 53(3), 296–307.

Watts, J. (2019). Assessing an online student orientation: Impacts on retention, satisfaction, and student learning. Technical Communication Quarterly, 28(3), 254–270.

Westberg, J., & Jason, H. (2001). Fostering reflection and providing feedback. Springer Publishing Company.

Whiteside, A. L. (2003). The skills that technical communicators need: An investigation of technical communication graduates, managers, and curricula. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 33(4), 303–318.

Wilson, G., & Dyke Ford, J. (2003). The big chill: Seven technical communicators talk ten years after their master’s program. Technical Communication, 50(2), 145–159.

Zimmerman, B. B., & Paul, D. (2007). Technical communication teachers as mentors in the classroom: Extending an invitation to students. Technical Communication Quarterly, 16(2), 175–200.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Julie Watts is professor of English at University of Wisconsin-Stout, where she teaches courses in document design, first-year composition, and theory and research. She is founding director of the M.S. Technical and Professional Communication. Her research interests focus on program assessment as well as the communicative dynamics and culture of the classroom learning community, and what instructors can do to facilitate student learning. She is available at wattsj@uwstout.edu.