By Rebekka Andersen and JoAnn Hackos

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Most refereed journals in the field of technical communication have as a goal to publish research articles on problems, trends, and practices in the field to meet the needs of readers working in both industry and academia. But academic researchers and journal editors know little beyond anecdotal stories about what industry readers actually think about the research articles they read in the journals.

Method: To better understand practitioner experiences with and perspectives on academic research, we conducted a 25-question survey of 187 practicing technical communicators. Questions focused on experience with trade and academic publications; interest level in reading academic articles based on titles and abstracts; types of publications and content found most useful, valuable, and relevant; and suggested changes for how academic research is designed or reported.

Results: The majority of respondents were either unfamiliar with or never or rarely read research published in the six main journals in the field. Common reasons given included difficulty finding and gaining access to journal articles, difficulty parsing practical applications, and difficulty making sense of dense and convoluted writing. But respondents also expressed strong interest in published research that has readily evident practical applications and relevance to current work practices.

Conclusion: Academic research in the field has the potential to reach and impact much wider audiences. We offer specific suggestions for how journals, professional organizations, researchers, and practitioners can better promote and increase access to published research and increase its relevance, value, and accessibility for industry readers.

Keywords: Academic research, value, relevance, accessibility, practitioner perspectives

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Practitioners are interested in academic research that is readily visible and accessible, that is relevant to current work practices, that emphasizes practical applications, and that is easy to read and understand.

- Practitioners can help shape the focus, design, and reporting of research by collaborating with researchers, offering work sites as study sites, serving on journal review boards, and offering journal editors constructive feedback.

- Practitioners can gain access to articles of interest by emailing authors directly or by looking for pre-published versions on Academia.edu, ResearchGate.net, or on the open access repository of a researcher’s institution.

INTRODUCTION

In November 2016, Technical Communication published a special issue on “Communication of Research Between Academic and Practicing Professionals,” edited by Mike Albers. The issue was devoted to exploring ways to improve the communication of research results between the field’s academic and practitioner communities. In his editorial introduction, Albers defined technical communication (TC) as a social science discipline with practical application and claimed that it thus stood “to reason that [TC] research should, if not be directly applicable, at least be understandable by those practitioners” (p. 293). But most academic research, he argued, was largely disconnected with practitioner research needs and poorly communicated to practitioners.

That special issue highlighted what we see as a significant problem facing the field of TC today: academic research, as both written and disseminated, is largely inaccessible to practitioners, and the value and relevance of the research to the problems that practitioners are trying to solve is often unclear (Albers, 2016; Blakeslee & Spilka, 2004; Clark, 2004; Dicks, 2002; Rude, 2015). Articles in the special issue described various dimensions of the academic and practitioner divide and offered research-informed recommendations for strengthening research-practice, academic-practitioner connections.

St.Amant and Meloncon (2016), for example, problematized the lack of practitioner voice in academic research and thus sought to better understand what research topics practitioners thought were important to examine and what research approaches they thought would work best to examine them. Through 30 asynchronous interviews with practitioners, St.Amant and Meloncon not only identified topics and approaches of interest but also learned that practitioners wanted more research to focus on real problems and audiences and to highlight applied results. Boettger and Friess (2016), too, found vast discrepancies in the topics most discussed in the field’s core professional and academic forums. To unify research, they called for more structured abstracts and implications statements across forums and for academics to identify new audiences and to engage more practitioners in their research.

Although the special issue from 2016 laid important groundwork for how the field can better sustain research-practice feedback loops, the issue as a whole focused more on identifying practitioner research interests, needs, and desired research approaches than on understanding practitioner experiences with academic research and practitioner-suggested strategies for improving the communication of research.

We thus wanted to build on the work published in that special issue by designing a study aimed to understand practitioner experiences with and perspectives on academic research, including practitioner suggestions for how the communication of academic research might be improved. We knew that to understand suggestions we needed to also understand underlying perspectives and experiences.

Our main research questions were as follows:

- What are practitioners’ experiences with academic publishing and/or research in technical communication?

- What kinds of academic research are practitioners most interested in reading and why?

- What kinds of publications and published content do practitioners find most useful for solving problems and/or improving processes and practices?

- How can the communication of academic research to practitioners be improved?

Our study included a 25-question survey of 187 practicing technical communicators, or people who worked as TC practitioners in non-academic contexts (e.g., as information developers, content strategists, technical editors). For each main research question, we asked a set of closed- and open-ended survey questions.

In this article, we offer a brief overview of the goals and intended audiences of the major research publications in the field followed by a brief discussion of why research focused on improving practice has been limited since the 1990s, despite several initiatives and numerous researchers who have called for and defined opportunities for conducting more research focused on practice. We then describe our study and report both quantitative and qualitative results of the survey. We end with a discussion of the primary concerns that practitioners raised about academic research, offering ideas for how journals and professional organizations might better promote and increase access to research and how authors and journals might increase the relevance, value, and accessibility of published research for non-academic readers. In this article, we use accessibility to refer to how academic research is both written and disseminated; we do not use accessibility to refer to the extent to which articles meet web or document accessibility guidelines.

BACKGROUND

The Need to Understand Practitioner Experiences with and Perspectives on Academic Research

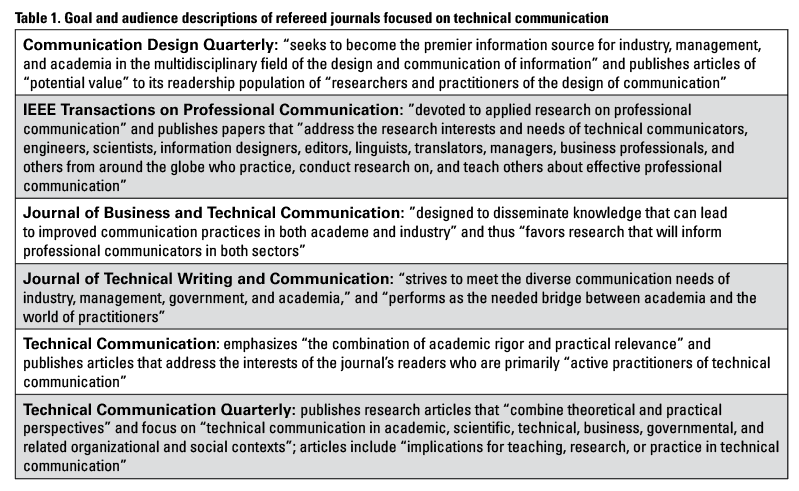

Practitioners’ experiences with and perspectives on academic research are important to consider because most refereed journals focused on TC have as a goal to publish research articles on problems, trends, and practices in the field to meet the needs of readers working in both industry and academia. As Table 1 shows, this primary aim is articulated in the aims and scope statements of five of the six refereed journals in the field (Technical Communication Quarterly being the exception, as its aim statement, at the time of this study, did not specify intended readers).

But neither authors of academic research nor journal editors or reviewers know much beyond anecdotal stories about what practitioner readers actually think about research published in the journals, including the extent to which they find the theory and research results applicable, relevant, and valuable. In an editorial in Technical Communication, deJong (2009) reflected on the journal’s aim of bridging the academic and professional world and commented, “I would be more than interested to see how technical communication professionals use and judge academic research contributions” (p. 98).

Research stakeholders would benefit a great deal from data that speaks to the frequency with which practitioners are reading the journals and the extent to which research topics and approaches, as well as the communication of research results, are meeting their needs.

The Disappearance of the “Improving Practice” Research Trajectory

It is no secret that academic research in TC has a reputation among practitioners of being irrelevant, too theoretical, too abstract, and difficult to access and understand. This reputation has been addressed in various publications and forums over the years (see, e.g., Albers, 2016; Andersen & Hackos, 2018; Bosley, 2002; Johnson, 2010 & 2018).

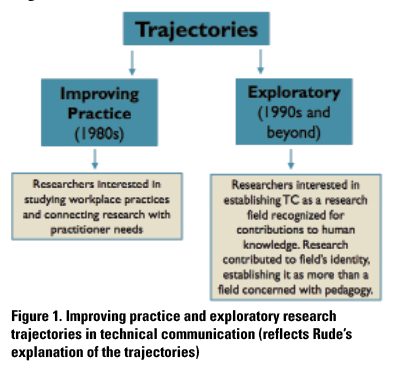

Rude (2015) explained the reputation in terms of the two research trajectories that the field has followed: the “improving practice” trajectory and the “exploratory” trajectory (see Figure 1). The improving practice trajectory was the focus of a great deal of research in the field in the 1980s and early 1990s; academic researchers were interested in studying workplace practices and connecting research with practitioner needs. Seminal works still referenced today include, among others, Rachel Spilka’s study of orality and literacy in the workplace (1990), Stephen Doheny-Farina’s study on writing in an emerging organization (1986), Karen Schriver’s Dynamics in Document Design (1996), and Dorothy Winsor’s Writing Like An Engineer: A Rhetorical Education (1996).

In a 1985 special issue of Technical Communication focused on “Research in Technical Communication,” editor Thomas Pinelli argued that the primary purpose of research should be to inform practice and that “good solid research advances the state of the art by contributing to the body of knowledge that in turn is applied to solve the numerous problems faced each day by practitioners” (pp. 6-7). At the time, research in the field had been limited; the issue thus served as a call for growing the body of research focused on TC, particularly research focused on the work problems practitioners needed to solve.

Beard, Williams, and Doheny-Farina (1989) noted in a follow-up article, “Directions and Issues in Technical Communication Research,” that despite wide agreement on the need for research that improves practice, practitioner input on research was largely lacking. To address the gap, the authors conducted a forum and survey at the 1987 International Technical Communication Conference to gather practitioner input on goals and directions for research as well as practitioner perspectives on published research in the field. The authors in particular wanted to find out if practitioners consulted published research and, if so, if they found it “valuable in solving their work problems” (p. 188). Interestingly, the vast majority of participants indicated that they regularly read published research, found the research helpful, and felt research was essential to evolving the profession (p. 190).

Rude (2015) suggested that interest in research focused on improving practice largely disappeared in the 1990s when the exploratory trajectory took off. She explained that researchers sought to establish TC as a research field recognized for its contributions to human knowledge; they thus began conducting research that focused primarily on “the ways in which texts act in the development and mediation of knowledge in a variety of settings” (p. 4). This research contributed to the field’s identity, establishing it as more than a field concerned with teaching and practice. A consequence of the exploratory trajectory pushing the boundaries of the field, however, has been limited research focused on improving practice.

Other cited reasons for limited research focused on improving practice include varied barriers to conducting applied research, particularly those of time, funding, rewards, and access. Blakeslee (2009), for example, found that researchers lacked the time, funding, and necessary institutional and departmental support and recognition (pp. 135-136). Further, promotion and tenure committees continue to value theoretical research and thus researchers on the tenure track often feel discouraged from conducting research designed to improve practice (a point Bosley, 2002, aptly makes).

The Many Calls for More Applied Research

Despite the challenges of conducting practice-focused research, many academic researchers agree that there is tremendous value in research that grows out of practice and that feeds back into practice (see, e.g., Albers, 2016; Andersen, 2011 & 2014; Rude, 2015). In fact, there have been numerous calls in the past 15 years for more research focused on improving practice. Davis (2013), for example, drew parallels between TC and other practice-oriented disciplines, arguing that “Ours is, like medicine and engineering, a discipline that must be immersed in solving real-world problems” (p. 30). Rude (2009), too, emphasized these parallels, suggesting that the knowledge we produce through research “must be recognized as enabling better work and use of the products it helps present to users” (p. 205). Interested in gauging the perspectives of 20 prominent researchers in the field, Blakeslee and Spilka (2004) found universal agreement that researchers need to investigate more research problems that industry considers important and that this research should lead to guidelines and best practices for the field.

The calls for more applied research and research that addresses defined needs have been answered by some. Two initiatives, the 2000 Milwaukee Symposium (see Mirel & Spilka, 2002, pp. xv-xvi) and the 2012 Industry/Academy Research Initiative (see Andersen, 2013a & 2013b; Benavente et al, 2013) serve as two prominent examples. The goals of both initiatives were to build stronger connections between research and practice and define shared research priorities—the outcome of both being a comprehensive list of research questions in need of scholarly and practical investigations aimed at improving practice.

Several seminal studies focused on improving practice, as well, have been published since the exploratory trajectory took off. These studies offer guidelines and heuristics that practitioners continue to apply to local contexts. Among others, example studies include Judy Ramey’s set of usability heuristics for website design (Ramey, 2000); Mike Albers’s and Loel Kim’s study of browsing behavior of users searching for information on a handheld device (Albers & Kim, 2002); David Dayton’s study of on-line editing by technical editors (Dayton, 2004); and Grice et al.’s usability heuristics and metrics for information products (Grice et al., 2013). These studies were published in Technical Communication and supported by the former STC Research Grants Program, which aimed to support practice-oriented research of value to practitioners. Other notable studies, also among others, have focused on best practices for creating instructional videos (ten Hove & van der Meij, 2015; Swarts, 2012); productive author-editor relationships (Eaton et al, 2008; Mackiewicz & Riley, 2003); strategies for increasing success in adoption of content management systems (Andersen, 2014; Gollner et al., 2015); project management for development teams (Lauren, 2018); and collaboration in international virtual teams (Brewer, 2015).

Research Methods

Given the aims of refereed journals in the field and renewed calls for more applied research, we wanted to learn the extent to which practitioners were reading research and whether they found the research helpful for problem solving. We wondered how experiences with and perspectives on academic research had changed since Beard, Williams, and Doheny-Farina (1989) conducted their survey of practitioner experiences and perspectives.

We thus designed a 25-question survey, employing what Creswell & Creswell (2017) called an “explanatory sequential design,” where the “intent is to first use quantitative methods and then use qualitative methods to help explain the quantitative results in more depth” (p. 6). Because we wanted to understand survey participants’ reasons for selecting the answers that they did, we included several open-ended questions on the survey inviting participants to share their stories and experiences. Responses to open-ended questions thus allowed us to better understand why participants viewed academic research the way that they did and how they imagined communication of academic research being improved to increase its value and relevance.

In addition to the survey, as part of a larger study, we conducted a series of interviews with practitioners who were established consultants or who were in managerial or senior positions in their organizations. We reported the results of the interviews in the paper “Increasing the Value and Accessibility of Academic Research: Perspectives from Industry,” published in the Proceedings of the 36th ACM International Conference on Design of Communication (2018).

Study instruments and recruitment materials underwent a full review from the UC Davis Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Survey Design

We designed the 25 closed- and open-ended question survey in an advanced version of Survey Monkey (Advantage Plan). The survey took respondents 30-45 minutes to complete.

The survey first asked questions about respondents’ roles as technical communicators and experiences with publishing in the field. It then asked respondents to review 18 titles and then 18 abstracts of articles published in recent issues of the six refereed journals in the field of TC (see Table 1). Titles and abstracts were included in the survey because we knew, based on our own experiences, that many practitioners would not be familiar with academic research; we thus wanted them to react to actual titles and abstracts rather than to assumptions or distant memories that they had about academic research. We selected three article titles from the most recent issue (as of May 2016) of the six journals. There were two exceptions:

Because one of us edited the March 2016 special issue and the September 2015 special issue of one of the journals, we included titles from the June 2015 issue (abstracts were included from the December 2015 issue).

Because the April 2016 issue of another journal focused on teaching and academic labor issues and the October 2015 issue included a series of commentaries from veteran academics, we selected titles from the July 2015 issue (abstracts were included from the January 2016 issue).

We selected 18 article abstracts from the same six journals in the issue published prior to the most recent issue, for a total of three abstracts from one issue of each journal (two exceptions described above). We did not include abstracts that focused on teaching or science policy or science communication. Journal editors, and in some cases editorial boards, granted us permission to use all abstracts included in the survey; neither the publishing journals nor article authors were identified.

We first asked respondents to review the titles and, next to each title, select their level of interest in reading the full article (Very Interested, Somewhat Interested, Not Interested). Respondents had the option of explaining why they might be interested in reading some of the articles but not others. We then asked respondents to review the abstracts and, next to each abstract, select their level of interest in reading the full article. Here, too, respondents were given the option of explaining their selections, and they were encouraged to describe their overall reaction to the article abstracts.

The survey ended with a series of closed- and open-ended questions about respondents’ personal experiences with and perspectives on academic publishing, including suggestions for how the design or reporting of academic research might be improved so to increase its relevance, value, and/or accessibility for practicing technical communicators.

Closed-ended questions included an “Other” option when appropriate and allowed respondents to enter their own answers (e.g., when asked to name the titles and/or areas of emphasis of the degrees or programs completed). Of the 23 closed-ended questions, seven offered respondents the option to “Please explain, if desired”—this option allowed us to collect qualitative comments to help us better understand quantitative selections.

We pilot tested the survey with three TC practitioners and revised it based on their feedback. The survey opened May 17, 2016 and closed June 28, 2016.

Survey Recruitment

We distributed the survey to a mailing list hosted by the Center for Information-Development Management (CIDM) and to 11 TC-focused LinkedIn groups that each had 1000 or more members. The CIDM is a professional organization that brings together managers of information development teams and thus largely comprises experienced practitioners in decision making positions; the mailing list included both members and non-members of the CIDM. The 11 TC-focused LinkedIn groups included the CIDM, Content Management Professionals, Documentation and Technical Writing Management, Documentation Managers, IEEE Professional Communication Society, Society for Technical Communication, Technical Writer Forum, Technical Writing and Content Management, Technical Writer in Action, Technical Publication and Documentation Managers Forum, and The Content Wrangler Community.

We used purposeful sampling in distributing the survey announcement and instrument to these groups because we wanted to specifically recruit practicing technical communicators. In the announcement that we sent to the CIDM mailing list and to the LinkedIn groups, we clarified our inclusion criteria through two opening questions: Are you a practicing technical communicator? Are you interested in research that can help you address problems and understand trends in the field? We followed these questions with the following statements:

If yes, please take this survey to help us identify how academic research in the field of technical communication can be better communicated and made more accessible to you. We want to hear about your experiences with and perspectives on academic research, and we want to know what kind of research you find most valuable and relevant.

For practicing technical communicators who might have felt disqualified due to not being familiar with academic research in the field, we further clarified that respondents did not need to be familiar with academic research to complete the survey and that the survey included sample titles and abstracts of research-based articles for their review and response.

All survey respondents, regardless of whether they completed the full survey, were invited to enter a drawing to win one of eight $50 Amazon gift cards.

Analysis

We did not attempt to establish statistical relationships among variables. For closed-ended responses, percentages and frequency counts were calculated by students enrolled in a Communication in Statistical Collaboration course at Virginia Tech (they were senior Statistics majors). The students conducted exploratory data analysis using descriptive statistics to create graphical representations of data distributions.

We analyzed open-ended responses looking for common themes in response to the questions. After identifying the main themes, we reviewed responses again and coded all instances of the theme. We then pulled comments that, in our professional judgement, best represented identified themes for each question.

Results and Discussion

In this section, we report descriptive results of the survey. We organize our reporting of results based on the five general categories of questions asked (these categories reflect our main research questions):

- professional and educational background

- experience with trade and academic publications focused on technical communication

- interest level in reading academic articles based on titles and abstracts

- types of publications and content found most useful, valuable, and relevant

- suggested changes for how academic research is designed or reported

Because not all respondents answered every question, we identify the number of respondents for each survey question. A total of 187 people took the survey.

Professional and Educational Background

Questions one through five asked respondents to share information about their professional and educational background. We first asked respondents to identify their role or roles in their organization and the number of years they had worked in the field of TC. We then asked respondents to describe their educational backgrounds.

Organizational roles and years in field

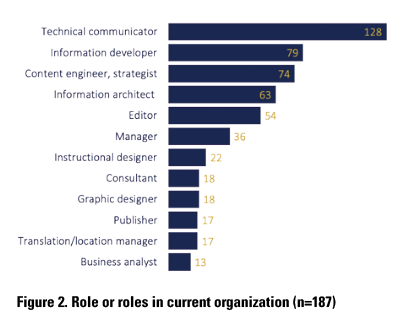

Respondents were asked to identify their role or roles in their current organization. We listed 17 roles plus an “Other (please specify)” option. The list is regularly used on surveys conducted by the CIDM. Figure 2 shows the range of roles represented by respondents (the total is greater than 187 because this was a “check all that apply” question).

Over 68% of respondents identified as technical communicators (n=128), while 42% identified as information developers (n=79) and 40% as content engineers or content strategists (n=74). The role of information architect (n=63) and editor (n=54) were also common. Given recent reports pointing to a decline in traditional technical writer roles and an increased need for people who can work with content at a strategic level (see, e.g., Kimball, 2016; Molisani & Abel, 2012), we were not surprised to see that nearly as many respondents identified as content engineers or content strategists as did information developers, a title that has largely replaced that of technical writer. Of those respondents who selected “Other” (n=23), however, six specified “technical writer” as their role.

Respondents were also asked to indicate for how long they had worked in the field. More than 70% of respondents (n=136) had worked in the field for more than 11 years, with 35% having worked in the field for more than 21 years (n=65). Notably, 56% of respondents indicated that they were working in management (n=105), and 35% had worked in management for four or more years (n=66). These numbers tell us that the majority of respondents were experienced technical communicators working in decision-making positions; the majority were thus well positioned to evaluate the relevance and value of academic research as well as to apply research results.

Educational background

We also wanted to know what degrees or programs respondents had completed as well as the titles and/or areas of emphasis of those degrees or programs.

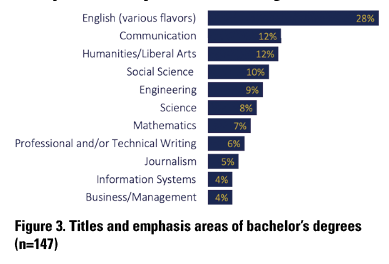

In total, 76% of respondents (n=140) reported having completed a bachelor’s degree or higher (of the total 184 respondents who answered this question). This percentage includes those who had completed a master’s degree (n=79), PhD (n=9), or post-baccalaureate program (n=4). Additionally, 21% of respondents (n=40) indicated that they had completed an academic or professional certificate, and 17% (n=32) indicated that they had completed a professional certification.

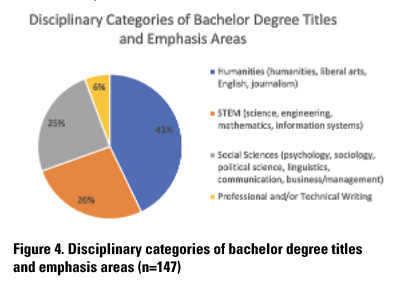

Of those who reported having completed a bachelor’s degree or higher, the disciplines or foci of the degrees varied widely. Degrees represented STEM fields, the social sciences, the liberal arts/humanities, and business/management.

Because respondents were asked to self-report titles and emphasis areas, answers were wide ranging and written in varied ways (e.g., “Communications” versus “Mass Media and Marketing”). We classified titles and emphasis areas into general disciplinary areas, as represented in Figure 3. Some respondents had completed two bachelor’s degrees and hence we received 147 responses (important to note given that only 140 respondents indicated having completed a bachelor’s degree). We did not specify what counted as an “emphasis area”; these might include minors, concentrations, or certificates.

We included in the “English (various flavors)” category titles and emphasis areas typically offered through traditional English Departments, such as “English literature and rhetoric” and “English, with an emphasis in writing.” Because we wanted to know how many respondents focused on professional and/or technical writing in their undergraduate education, we counted any titles or emphasis areas that mentioned professional and/or technical writing (or communication) as a separate category. If a respondent completed a bachelor’s degree in English with a concentration in professional writing, for example, we counted that response as professional and/or technical writing, not English. However, if a respondent listed three emphasis areas, such as political science, philosophy, and business and technical writing, we counted that response as three unique areas (Social Science, Humanities/Liberal Arts, and Professional and/or Technical Writing); thus, the total percentage of titles and emphasis areas added up to more than 100%.

Figure 4 presents the breakdown of degree titles and emphasis areas according to disciplinary categories (with Professional and/or Technical Writing listed as its own category).

Only 6% of respondents (n=9) listed technical and/or professional writing (TPW) as their degree title or emphasis area. Seven in this count had English or Communication degrees with an emphasis in TPW. Two had full-fledged degrees (meaning required core courses and elective courses focused on various aspects of TPW).

Survey results indicate that most respondents who studied TPW at the college level did so in a graduate program. Of the 79 respondents who had completed a master’s degree (43%), 26 listed technical and professional communication (TPC) as their primary area of study (note the shift from “writing” at the bachelor’s level to “communication” at the master’s level). This means that roughly 14% of the technical communicators who completed the survey (n=187) had studied TPC at the graduate level (we did not ask those who had completed PhDs to list degree titles or areas of emphasis). It was not clear if the 9 respondents who focused on TPW in their bachelor’s program had completed masters’ degrees and, if so, what they had studied.

Of the 40 respondents who had completed a professional or academic certificate (22%), half had completed certificates in TPC.

These numbers tell us that a good number of respondents were not likely to have been exposed to academic research in TC as undergraduate or graduate students. Those who had completed undergraduate degrees in fields other than TPC may have read research in a required technical writing service course, and we can safely assume that the 14% of respondents who had completed master’s degrees in TPC were exposed to a range of research methods and publication venues in the field as graduate students. But most respondents, if they were familiar with academic research in TC, would have likely learned about that research outside of a TPC degree or certificate program.

Experience with and Access to Trade and Scholarly Publications in Technical Communication

In this section of the survey (Questions 6 through 15), we asked respondents to share their experience with reading, authoring, and/or reviewing trade and scholarly publications focused on TC topics.

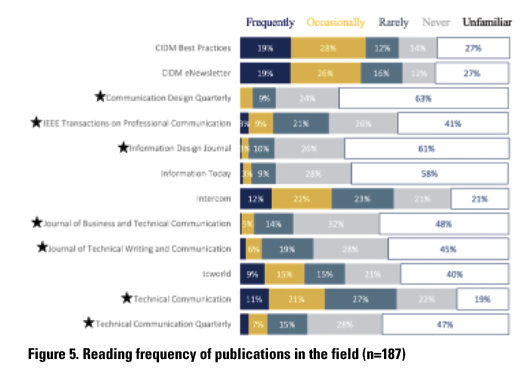

To determine reading frequency of established publications in the field, we asked respondents to indicate how often they read or skim a particular publication. We listed seven journals (all refereed) and five trade magazines or newsletters. Respondents could select frequently, occasionally, rarely, never, or unfamiliar. Respondents were asked to select “unfamiliar” if they had not heard of a publication. Figure 5 shows reading frequency (refereed journals are starred).

Not surprisingly, trade publications were read more frequently than scholarly publications, with the exception of Information Today, an online magazine geared toward professionals in the information industry (not specific to TC). Because we recruited participants from the CIDM mailing list and 11 TC-focused LinkedIn groups, including the STC LinkedIn group, we were also not surprised to see that 47% of respondents frequently or occasionally read the CIDM Best Practices newsletter (available to CIDM members), 45% the CIDM eNewsletter (free access), and 34% the STC trade magazine, Intercom (available to STC members).

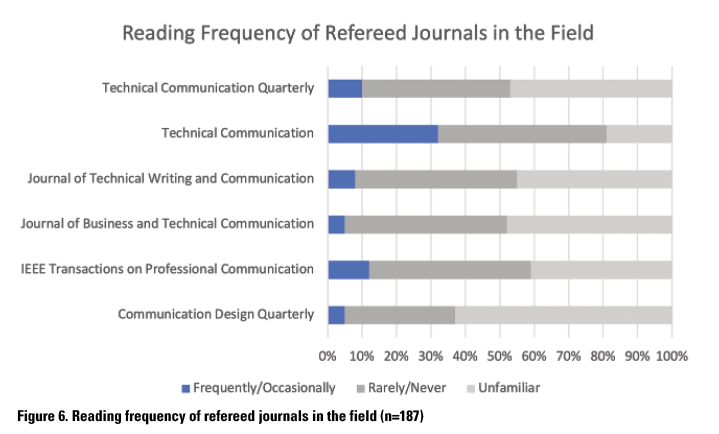

We were surprised, however, by the number of respondents who indicated that they were either unfamiliar with or rarely/never read refereed journals in the field. Figure 6 shows a breakdown of how often respondents read or skimmed these publications. We grouped Frequently/Occasionally, Rarely/Never, and Unfamiliar to get a better sense of reading frequency.

The vast majority of respondents were either unfamiliar with or rarely/never read five of the six refereed journals in the field. The journal Technical Communication was the exception; 32% of respondents indicated that they frequently or occasionally read the journal, a number that may reflect the number of respondents who indicated that they were STC members (n=56, or 30%). Other organizational memberships included the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) (n=10, or 5%), which publishes IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, and the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) (including SIGs) (n=8, or 4%), which publishes Communication Design Quarterly. Members of these organizations can access their publications for free (non-members must pay a subscription fee or be affiliated with a university to access them). The low percentage of respondents who were members of IEEE or ACM may in part explain the high percentage of respondents who were unfamiliar with or rarely/never read their respective journals.

The Journal of Business and Technical Communication, Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, and Technical Communication Quarterly are accessible via direct subscription (institution or individual) or through university libraries (primarily faculty members and students have access, though some organizations do give access to library holdings); this may be another explanation for reading frequency results. The low percentage of respondents who had completed degrees in TPC may, in part, also explain the number of “unfamiliar” responses.

But we also gave respondents an opportunity to explain their reading frequency selections. Reasons given among the 26 respondents (of 187) who offered an explanation included lack of budget for subscriptions and thus lack of access (n=11), preference for other publications (n=4), lack of relevance (n=3), lack of familiarity (n=3), lack of time (n=3), and poor readability (n=2). Notably, all reasons respondents gave focused on why they selected rarely, never, or unfamiliar. Some did not read because they simply did not have access to or did not know where to find research; others did not read because they did not find the research relevant or they found it too difficult to sift through.

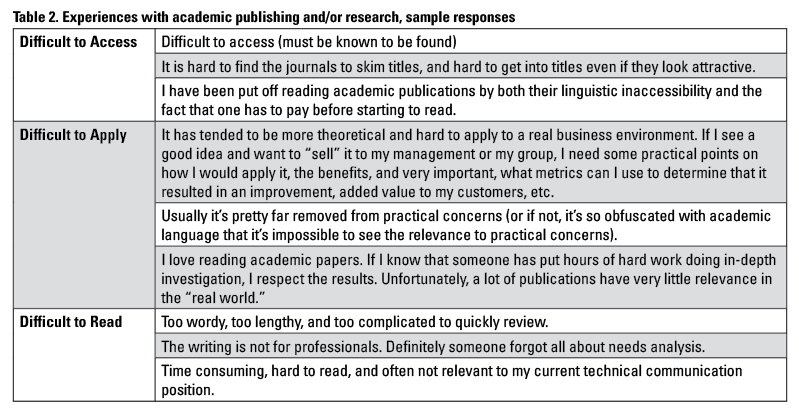

More telling explanations for reading frequency selections came from the final question of our survey (Q25): What is your experience, in general, with academic publishing and/or research? We received 107 responses to this open-ended question: some respondents opted to describe their experience with academic publishing (e.g., as an author of several articles, as a member of a review board) while others opted to describe their basic familiarity with academic research (e.g., “No experience” or “Read some academic articles in college”). Yet others opted to share their experiences as readers of academic research in the field of TC. Of the respondents who commented specifically on their experience as readers (n=44), 5 reported positive experiences and 39 reported negative experiences linked to three frustrations: difficulty finding and gaining access to journal articles, difficulty parsing practical applications, and difficulty making sense of dense and convoluted writing.

Table 2 includes sample responses that capture these frustrations.

In addition to asking respondents about the frequency with which they read trade and scholarly publications in the field, we asked them several questions about authorship. Of the 187 respondents, 33 (18%) had published experience-based or research-based content (e.g., survey results, case study) in a trade publication (e.g., white paper, magazine, newsletter). Of these, most had published a magazine or newsletter article or a blog post.

We also asked respondents if they had published experience-based or research-based content in a scholarly publication (e.g., a refereed book, edited collection, or journal). Only 16 respondents (8.5%) said yes, with 14 indicating that they had published a refereed article and 10 indicating that they had published a chapter in a refereed edited collection (some respondents had authored multiple publications). A higher number of respondents had experience with the academic publishing process through serving as a reviewer for a scholarly publication (n=41, or 22%) or serving on the editorial board of an academic journal (n=11, or 6%). These numbers suggest that about a quarter of respondents (25%) were familiar with the process by which research gets vetted and published in scholarly publications.

Overall, results for this section of the survey indicate that the majority of the 187 respondents, all of whom identified as practicing technical communicators, were either unfamiliar with or rarely/never read scholarly publications in TC. Those who frequently/occasionally read or rarely/never read research articles tended to find them difficult to access, read, and apply. We speculate that the 25% of respondents who had experience with the academic publishing process as authors, reviewers, or editors likely read research articles with more frequency than those without experience.

Interest Level in Reading Journal Articles Based on Titles and Abstracts

Questions 16 and 17 asked respondents to indicate their level of interest in reading a journal article based on its title or title plus abstract and to explain why they might be interested in reading some articles but not others. We included titles and abstracts in the survey because we knew that many practitioners would not be familiar with academic research and thus we wanted them to react to actual titles and abstracts rather than to assumptions or distant memories that they had about academic research.

Question 16 listed 18 titles of articles published in the most recent issues of six refereed journals in TC (three titles each). Only article titles, not author names or publication titles, were given. Next to each title, we asked respondents to select Very Interested, Somewhat Interested, or Not Interested.

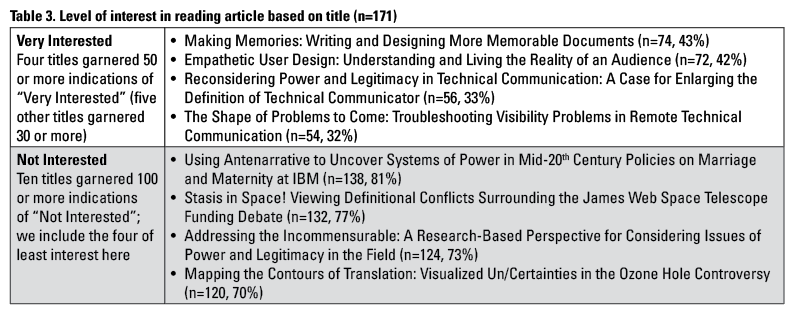

Table 3 includes the titles of articles that respondents (n=171) were most interested and least interested in reading.

The four titles of most interest to respondents focused on either improving the user experience or understanding changing job roles (see Table 4). The articles held the promise of helping readers understand how they might improve the user experience through better writing and design or how they might better argue for the value they bring to their organizations. Below is a sampling of comments that represent the most cited reasons why respondents selected “Very Interested” (note: 100 respondents offered comments):

- “Most selected have more of a practical application to the work I do. The remainder are areas of interest but I don’t have the time to pursue and, finally, the remainder are way too esoteric.”

- “The articles that interest me seem to be written on a subject that would impact my work.”

- “I am very interested in articles that address the influence and expanding role of technical communicators. I like to know where I can contribute in that role.”

- “I’m interested in articles which help me do my work better and more easily, or which directly contribute to my advancement as a communicator or as a human being. I’m not so interested in articles which are aimed solely at other academics or which appear to be navel-gazing.”

- “It’s the combination of a subject that interests me with a title that indicates minimal academic jargon. Academics who write about technical communication should make an extra effort to be clear and direct.”

The four titles of least interest to respondents did not convey clear practical applications and/or were considered too academic or obscure. Below is a sampling of comments that represent the most cited reasons why respondents selected “Not Interested” (note: 100 respondents offered comments):

- “Some of the titles are so long and full of jargon that I don’t hold out much hope for the article to be more engaging than the title.”

- “Some [titles] seem too academic and I do not feel like I can learn anything applicable to my role or future roles as tech writer”

- “Most of the titles are dreadfully off-putting, and academic articles are often poorly written with little obvious connection to real-world applications. If the title sounds really pretentious or obscure, I’m not interested.”

- “I look for keywords or phrases that I’m interested in: examples in this list would be personas, definition of technical communication, crowd-sourced help. If the title contains words that seem like academic jargon, I’m almost certain to put the article in the “not interested” pile. Examples: antenarrative, incommensurable.”

- “These titles seem too far removed from my daily work experience; sometimes it is difficult to tell from the wording of the title whether the article might be of interest.”

Results for Question 17 further pointed to respondents’ overall desire for articles that had practical applications and were written in plain language. Question 17 asked respondents to read or skim 18 article abstracts (with titles) from the same six journals (three abstracts each); the abstracts were published in the second most recent issue at that time. After skimming or reading the title and abstract, respondents were asked to select their level of interest in reading the full article: Very Interested, Somewhat Interested, or Not Interested. Only article abstracts, not author names or publication titles, were given.

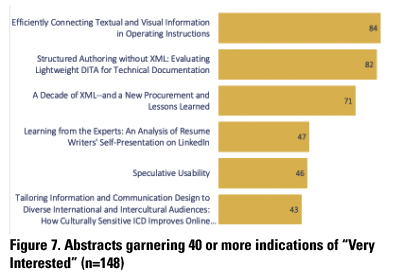

Figure 7 presents the titles of articles that respondents indicated they would be “Very Interested” in reading after having read or skimmed the article abstract. Six of the 18 articles garnered 40 or more indications of “Very Interested” (n=148); that is, 27% of respondents indicated a strong interest in six articles. Only three of those six were selected by half (50%) or more of all those who responded to the question.

What all of the titles and abstracts in Figure 7 have in common is the promise of offering readers a practical takeaway—something that they could take back to their teams and apply to the benefit of their organization or customers. The titles and abstracts also focused on topics relevant to respondents’ current work practices or projects.

Notably, the abstracts associated with these titles were also well structured with clear headings. “Efficiently Connecting Textual and Visual Information,” for example, included the following bolded headings: research problem, research questions, literature review, methodology, and results and conclusions. Readers could quickly skim through the abstract to determine if the topic was of interest. One respondent wrote that she “appreciates chunked, multi-part abstracts” over those presented as “walls of text.” Only two of the six journals included in the survey (namely, Technical Communication and IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication) required authors to write structured abstracts with set headings, and five of the six titles and abstracts represented in Figure 7 are from those two journals. Worth noting here, as well, is that while several respondents appreciated the headings, they did not like the long block of text interrupted by only bold words in IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication. The lack of a visual hierarchy and white space discouraged reading.

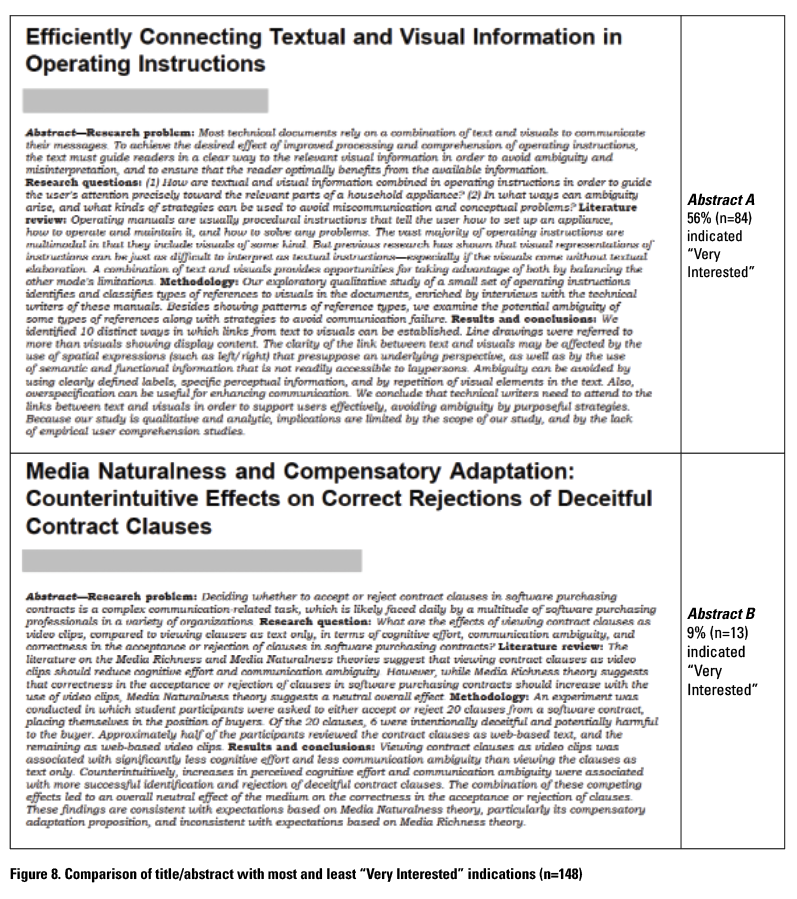

Titles and abstracts garnering the most “Not Interested” indications were described by respondents as not having any practical application, not being relevant to current work projects, and/or being too academic, esoteric, or difficult to parse. Figure 8 presents a comparison of the title and abstract that received the most “Very Interested” indications to the title and abstract that received the least “Very Interested” indications. Both articles were published in the same issue of IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication.

Abstract A describes a qualitative study that addresses two research questions: “(1) How are textual and visual information combined in operating instructions in order to guide the user’s attention precisely toward the relevant parts of a household appliance? (2) In what ways can ambiguity arise, and what kinds of strategies can be used to avoid miscommunication and conceptual problems?” The questions suggest to readers that the article will help them to both better understand and improve the user experience. The results and conclusions also point to a research-supported strategy that readers can apply: “We conclude that technical writers need to attend to the links between text and visuals in order to support users effectively, avoiding ambiguity by purposeful strategies.” The title and abstract are further written in plain language (i.e., use of active voice and pronouns to speak to the reader; closeness of subject, verb, and object in independent clauses).

Abstract B, by contrast, presents the results of an experiment focused on the acceptance or rejection of software contract clauses delivered as text or video. Researchers asked, “What are the effects of viewing contract clauses as video clips, compared to viewing clauses as text only, in terms of cognitive effort, communication ambiguity, and correctness in the acceptance or rejection of clauses in software purchasing agreements?” The question suggests to readers that the article will help them understand the effects (or outcomes) of viewing clauses as video clips versus texts, but unlike Abstract A, the question does not imply whether the article will focus on practical applications. The results and conclusions focus solely on the theoretical, leaving practitioner readers without a sense of how the article might be useful: “These findings are consistent with expectations based on Media Naturalness theory, particularly its compensatory adaptation proposition, and inconsistent with expectations based on Media Richness Theory.”

While Abstract B certainly focuses on a topic with potential practical applications, the abstract does not point to what these applications might be nor for whom, and the writing overall is much harder to parse than that of Abstract A.

Types of Publications and Content Found Most Useful, Valuable, and Relevant

The next series of questions in the survey asked respondents to indicate the types of publications and content that they have found most useful, valuable, and relevant as practicing technical communicators. We wanted to know what respondents read and why, and we also wanted to know if they would be interested in reading research-based articles on topics of interest and relevance to them. We briefly summarize results of these questions below.

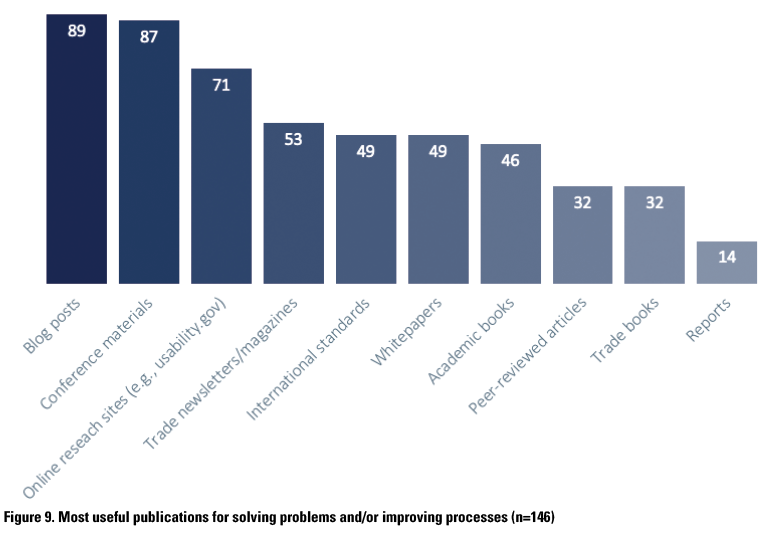

Question 19 asked respondents what types of publications they had found most useful for solving problems and/or improving processes and practices. Figure 9 presents results for the 10 publication types listed (respondents could check all that apply).

Blog posts, conference presentations and proceedings, and online research sites such as usability.gov and plainlanguage.gov were deemed the most useful publications, with trade newsletters/magazines, international standards, and white papers close behind. A good number of respondents also found academic books (n=46, or 32%) and peer-reviewed articles (n=32, or 22%) useful, though explanatory comments indicated that some respondents conflated academic and trade books. In addition to perceived usefulness, the lower numbers for scholarly publications overall likely reflect respondents’ lack of familiarity with and access to academic research.

Blog posts, conference presentations and proceedings, and online research sites such as usability.gov and plainlanguage.gov were deemed the most useful publications, with trade newsletters/magazines, international standards, and white papers close behind. A good number of respondents also found academic books (n=46, or 32%) and peer-reviewed articles (n=32, or 22%) useful, though explanatory comments indicated that some respondents conflated academic and trade books. In addition to perceived usefulness, the lower numbers for scholarly publications overall likely reflect respondents’ lack of familiarity with and access to academic research.

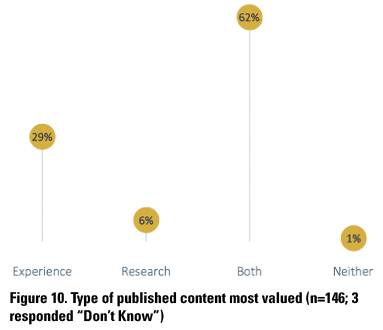

We then asked respondents what type of published content they most valued (Question 20). We wanted to know if they preferred content based on experience (e.g., experience reports that describe a problem or situation and the applied solution) or content based on research (e.g., an empirical study that uses quantitative or qualitative methods to examine a problem or question). Options included content based on experience, content based on research, I value both types equally, I do not value either type, and don’t know.

Respondents largely valued both experience-based and research-based content, as shown in Figure 10.

Respondents largely valued both experience-based and research-based content, as shown in Figure 10.

While only 15 respondents offered explanations for their selection, responses were illuminating. Several respondents emphasized the need for research and experience to co-exist, highlighting the value of insights gleaned from experience and recommendations based on results of a rigorous methodological study. One respondent explained the difference in value added this way: “Research tells you what can work and how, while experience often tells you why it worked or how to adjust in case adjustments are required.” Another offered the following response: “To solve a practical problem, experience-based is better. To answer bigger more complex questions, research is usually more trustworthy.” Results of this and previous survey questions suggest that practitioners value valid and reliable research data to guide decision making, but they find research that is irrelevant to the questions they need to ask or problems they need to solve of little value.

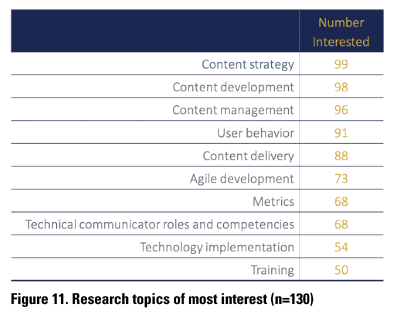

To determine what kind of research practicing technical communicators would be most interested in reading, we asked a follow-up question: Would you be interested in reading research-based articles (quantitative and qualitative studies, content analysis studies, systematic literature reviews) that examine topics such as content strategy, user behavior, metrics, and processes (e.g., content development, content delivery, technology implementation)? The topics listed were drawn from results of a previous survey that asked participants of the 2012 CIDM Best Practices Conference to list and describe topics for which they would appreciate having research data (Andersen, 2013a).

An overwhelming 89% of respondents (130 of 146) answered “Yes” to being interested in reading research-based articles on these topics. Those who answered “Yes” were then asked to select which topics for research-based articles would be of most interest (they could check all that apply). Figure 11 presents a breakdown of level of interest.

All topics were of interest to some respondents, with topics directly relevant to current information development practices of most interest (those focusing on how best to plan, create, manage, and deliver modular content for reuse and multichannel publishing). The results reflect respondents’ overall desire for published research that has readily evident practical applications and relevance to current work practices.

All topics were of interest to some respondents, with topics directly relevant to current information development practices of most interest (those focusing on how best to plan, create, manage, and deliver modular content for reuse and multichannel publishing). The results reflect respondents’ overall desire for published research that has readily evident practical applications and relevance to current work practices.

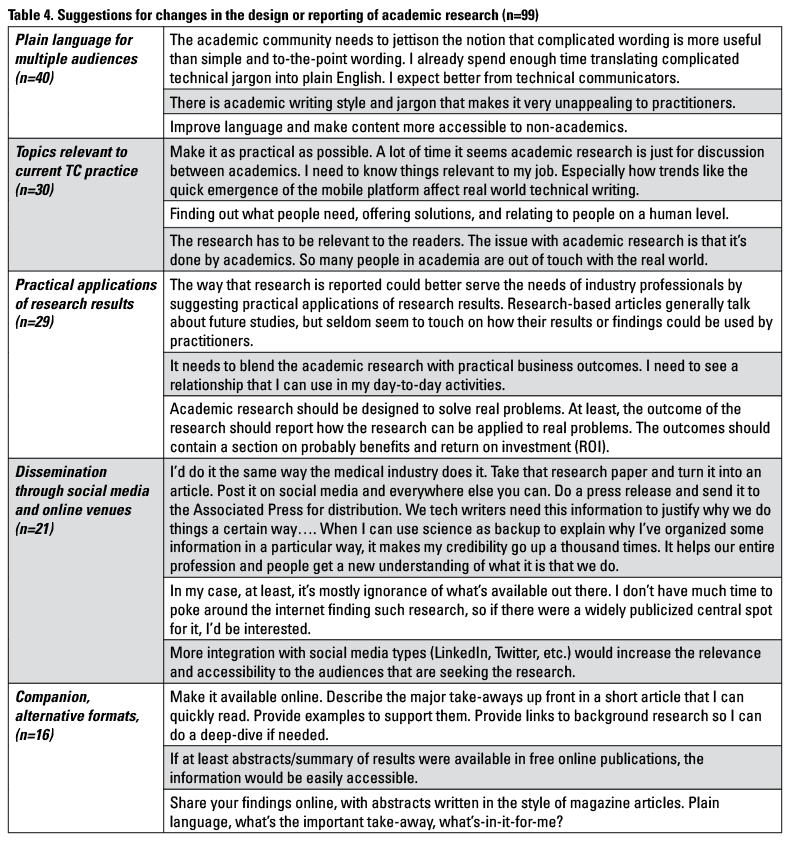

Suggested Changes for How Academic Research is Designed or Reported

At the end of the survey, we offered respondents an opportunity to share suggestions for how academic research in TC might be better designed or reported to increase the relevance, value, and/or accessibility of the research to practicing professionals.

Themes that emerged from our coding of responses (n=99) included a desire for research articles that

- are written in plain language with multiple audiences in mind (n=40),

- focus on topics relevant to current technical communication practice (n=30),

- focus on practical applications of research results (n=20),

- are disseminated through social media and other accessible online venues (n=21), and

- are written in companion, alternative formats emphasizing main points, results, and takeaways (n=16).

Respondents who wanted to see more research relevant to current practices also tended to comment on the need for research-based articles to explain how results can be used by practitioners. We saw these themes as related but distinct and thus coded them as such. The same pattern was found in comments calling for research to be easily discoverable (better promoted) and to be structured and formatted in such a way as to allow for quicker distillation of main points, results, and takeaways.

Table 4 presents sample suggested changes that represent the main themes that emerged from our coding of responses.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Survey results indicate that practicing technical communicators are interested in academic research that is readily visible and accessible, that is relevant to current work practices, that emphasizes practical applications, and that is easy to read and understand. These results align with those of St.Amant and Meloncon (2016) and Boettger and Friess (2016) and do not necessarily offer new insights into practitioners’ experiences with and perspectives on academic research. But they do reinforce the need for authors and journals to do more to reach and engage technical communicators working in the profession.

The majority of our survey respondents were either unfamiliar with or never or rarely read research published in the six main refereed journals in the field. We did not find this result surprising given the low percentage of respondents who had degrees in the field (and thus would likely not have been exposed to TC research in college). Even so, respondents overwhelmingly were interested in knowing about relevant and potentially useful research, and many, through explanatory comments, acknowledged the value of empirical studies over anecdotal stories or experiential reports. Results gleaned from empirical studies can lend credibility and authority to business cases for resources, initiatives, or changes needed to improve processes or solve problems.

It is clear from our survey and series of interviews (see Andersen & Hackos, 2018) as well as from the results of studies published in the November 2016 special issue on “Communication of Research Between Academic and Practicing Professionals” that academic research in the field—in both its design and reporting—has the potential to reach and impact much wider audiences. In the next sections, we offer ideas for how journals and professional organizations might better promote and increase access to published research and for how authors and journals might increase the relevance, value, and accessibility of practice-oriented research for non-academic readers.

Promotion

Academic research is not well promoted. When a new journal issue or book is published, an announcement is occasionally made on one of the academic listservs, such as the Association of Teachers of Technical Writing or the Council for Programs in Technical and Scientific Communication. Academics in general know to browse the table of contents of journals in the field every few months, as the issues are published quarterly. But journals and book publishers seldom promote issues, individual articles, or books in social media groups or on online platforms frequented by industry readers.

Because academics rely on published research for teaching and for conducting their own research, they are well trained to find and motivated to seek out research on particular topics, either through searches on Google Scholar, university library databases, or journal websites. The model for promoting academic research in TC has tended to rely on a “pull” rather than “push” approach.

What this means is that academic research, particularly new research, may not be on the radar of many practicing technical communicators. And given that many practitioners come from other disciplines and programs of study and thus may not be aware of the field’s research journals, they may not know to even look for academic research on particular topics (more than 40% of our respondents were not aware of five of the journals). One of our respondents offered the following comment:

Honestly, I didn’t know how much research-based content was available until I started this survey. We need to spread the word a LOT more. Suddenly, I feel like I’ve been living under a rock! This is fascinating, important work and should be celebrated and expanded on!

Given that research journals in TC have as a goal to meet the needs of readers working in industry and academia, we encourage journals and other research stakeholders to find more ways to promote articles in venues frequented by practitioners. The Recent and Relevant column in Technical Communication represents one effort to do so. The column, available to STC members in the online version of the journal, provides readers “an efficient way to keep up with technical communication scholarship in a variety of journals that readers might not have time to check individually.”

Some preliminary ideas for how journals, authors, and professional organizations can better make research relevant to practitioners more visible are as follows:

Some preliminary ideas for how journals, authors, and professional organizations can better make research relevant to practitioners more visible are as follows:

- Publicize new journal issues and articles through social media. There are dozens of active TC groups on LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook, and article titles and abstracts that highlight practical applications are likely to be noticed.

- Create a social media presence for each journal to allow readers in industry and academia to follow them on different platforms. When promoting research relevant to practitioners, journals might tag practitioner groups and highlight practical applications of research results. Doing so will bring more traffic to sites on which the journals have a presence and in turn raise the visibility of published research.

- Promote published research relevant to practitioners at industry conferences. One survey respondent recommended that conferences set aside a segment of their agenda to focus on results of academic research for the topic of that conference. Titles and abstracts of relevant research articles might also be included in the conference program or in a section of the conference proceedings.

- Promote published research on existing online repositories. Example repositories include the STC Technical Communication Body of Knowledge (TCBOK) and the Crowdsource Technical and Professional Communication project spearheaded by Chris Lam of the University of North Texas.

Practitioners, too, can increase their exposure to published research by following the journals on social media and by signing up for new content alerts on the Stay Connected sections of the websites for JBTC, JWTC, and TCQ. Alerts are communicated through email or RSS feeds.

Access

Because access to journal articles requires an individual or institutional subscription to a journal, a membership to a professional organization, or a student or faculty affiliation with a university, many practitioners do not have a way to read the full text of articles of interest. Fewer organizations, as well, have budgets for journal subscriptions or organizational memberships, further limiting practitioners’ access to published research in the field. Individual journal articles can be purchased (fees range from $30 to $45), but as our survey findings reveal, the titles and abstracts often do not communicate the value of individual articles to practitioners—and titles and abstracts are the only article content accessible from journal websites and Google Scholar (unless an article has been unlocked allowing full access). If the value of an article is not clear, and if the title and abstract are difficult to parse, practitioners are not likely to want to purchase the article.

In a blog post, Tom Johnson (2010) lamented how inaccessible the field’s journals are to practitioners, suggesting that “for a discipline geared towards improving the profession, cloistering up the research makes no sense.” We agree, but we also recognize that the for-profit publishing model on which three of the journals operate is not going to change anytime soon, nor is the organizational membership model on which the other three journals operate. Journals additionally must cover publishing, editing, and production costs.

Most TC journals offer authors the option to publish open access, which allows authors to post and share their work free of charge anywhere, anytime, no restrictions. However, this option comes with a steep fee. For example, Taylor and Francis, which publishes Technical Communication Quarterly, charges authors an article publishing charge (APC) of $2995.00; likewise, SAGE, which publishes the Journal of Business and Technical Communication and the Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, charges $3000.00. The vast majority of authors (including their non-profit or for-profit employers) cannot afford this fee and receive no recognition or reward (through performance or promotion and tenure reviews) for paying to make their work accessible to a broader audience.

Making journal articles easier for practitioners to access is a crucial step toward increasing the impact of academic research on TC work in non-academic contexts. To increase access and, by logical extension, readership, journals might consider offering online subscriptions and online access to specific articles at as low a price point as possible within their business models. Professional organizations sponsoring journals might also consider offering online subscriptions separate from membership dues, allowing non-members access to journals at an affordable price point. Doing so may raise the profile of research sponsored by the organizations and in turn attract new dues-paying members who are interested in other tangible benefits of membership.

Given our survey findings, we think another good way to increase practitioner access to research is for journals to offer alternative, companion formats for articles of relevance to practitioners. Numerous respondents called for short articles in executive summary format, written in a magazine style, that explain how research results might be applied in particular contexts or to particular problems; they were interested in being able to quickly locate a study and determine its value and relevance for workplace practice. St.Amant and Meloncon (2016) and Boettger and Friess (2016) made similar recommendations based on their research findings.

Offering companion articles would allow journals to better promote articles, reaching a wider audience, and to increase readership—companion articles may also encourage readers to purchase the original article. Communication Design Quarterly (CDQ) has recently launched an Abstract Showcase that could serve as a model, though the abstracts are not yet searchable online. Other venues with potential for disseminating companion articles include STC’s Notebook blog and the Communication Resources section of the IEEE ProComm website. Journals or professional organizations might also consider sponsoring a research seminar or podcast series. CDQ has also recently launched a podcast “to promote key articles and increase awareness of the publications” (the first episode was released in February 2020).

We envision journal editors inviting authors who publish research on topics relevant to practitioners to write companion articles. However, formal recognition for these important contributions to the field will be essential, as many authors do not publish in venues read by practitioners because academic personnel committees continue to value and reward refereed publications, often dismissing other publication types for having little “impact.” Practitioner authors may also benefit from official recognition.

To increase access to academic research, we further suggest that authors consider posting pre-published versions of articles on Academia.edu and ResearchGate.net, social networking sites for sharing research, as well as on open access repositories such as Open DOAR, which lists open access repositories for each university that makes articles by its faculty available to the public. We suggest, as well, that authors in academia post pre-published versions of articles in the open access repository of their university (the UC system, for example, uses eScholarship to support faculty in increasing the reach of their scholarship); these repositories are designed to make research articles authored by faculty available to the public at no charge. Each of the journal publishers allows for authors to post their accepted manuscripts (pre-proof stage) on any websites, repositories, or social media channels.

Relevance and Value

Rude (2009), in mapping the research questions most examined in the field, identified four categories into which research tends to fall. These include disciplinarity (e.g., What are our definitions, history, status, possible future, and research methods?), pedagogy (e.g., What should be the content of our courses and curriculum?), practice (e.g., What design practices are inclusive of international users and users with disabilities?), and social change (e.g., How do texts function as agents of knowledge making, action, and change?). These categories of research remain essential in an ever-evolving and changing field, and the questions that emerge within them continue to require different research approaches (e.g., social, critical, theoretical, empirical).

Regardless of the foci of research or approach taken, however, our survey findings reveal that authors can do more to articulate the value and significance of their research for readers working in both industry and academia. For example, an author might explain how a practitioner can use a theoretical framework to examine or think through a particular problem or situation, or use the results of a content analysis of several websites to inform accessible design considerations for content portals. In the series of interviews that Andersen & Hackos (2018) conducted with practitioners, one interview participant offered the following perspective on what she saw as the value of theoretical research:

Exposing and illustrating the utility of theoretical frameworks is useful to practitioners and can be used to improve practice or the thinking about practice. The practitioner sourced articles can lean toward superficiality so these theoretical frameworks can help practitioners perform better work and certainly to improve how they communicate what they have observed or learned.

Respondents of our survey offered similar perspectives. They were interested in a variety of research topics and approaches, but they were not interested in reading articles that spoke only to other academics. We want to note, as well, that many respondents did not find brief practitioner takeaways or implications for practice sections useful; in fact, a few mentioned how these sections sometimes seemed like afterthoughts or add-ons. They wanted to see discussions of practical applications connected to actual use cases, and they wanted authors to make applications explicit rather than expecting readers to figure them out.

St.Amant and Meloncon (2016) encouraged authors to ask who they envision as benefactors of their research, how they can best communicate their research to these benefactors, and how their research projects contribute to the larger whole (p. 274). These are important questions given the aims of research journals in the field. The larger whole includes both the profession and the discipline of TC, yet readers in the profession often feel that they are not intended benefactors of published research.

In addition to the suggestions already discussed, we offer the following ideas for how research stakeholders might increase the relevance and value of published research for non-academic readers:

- All stakeholders. Encourage researcher-practitioner collaborations, in the design and reporting of research projects. Professional organizations and journals are best equipped to connect academics and practitioners with mutual research interests and provide an infrastructure to support research collaborations (e.g., post call for proposals, create forums for match-making, create awards for articles with measurable impact on practice). Practitioners could propose research questions and studies needed, and academics could help categorize, refine, and consolidate questions and proposed studies. Practitioners might also ask their organizations if they’d be willing to fund a study that promises a clear return on investment.

- All stakeholders. Make it easier and more desirable for researchers to conduct studies at work sites and recruit practitioners as subjects (as opposed to students). Several survey respondents noted that studies that only use student subjects are less likely to be convincing and useful. Practitioners can volunteer work sites and provide researchers access, and academic administrators can revise standards for promotion and tenure to recognize the time commitment for conducting work-site research and reward such research in review processes.

- Journals. Revise submission guidelines and templates to encourage authors to address the value and significance of their research for both industry and academic readers in article abstracts and introductions. Journals should also provide clear guidelines for writing sections on implications for practice. Editorial boards might consider hosting workshops for authors at conferences on how to articulate the relevance and value of their research for non-academic readers.

- Journals and practitioners. Recruit more practitioners to review manuscripts and periodically seek their feedback on the extent to which journals are meeting the needs of industry readers. Practitioners, too, can contact journal editors to express interest in serving as a reviewer; in this role, they can help shape the communication of research and the practical value of results.

- Academics. Design studies that address research questions that grow out of practice and feed results back into practice to improve practice, at which point new research questions might be generated. Writing alternative, companion articles that practitioners can easily find, read, and use is one way to feed results into practice.

Writing Style

Better promoting and increasing the accessibility, relevance, and value of academic research for non-academic readers will positively impact these readers’ perspectives on and experiences with academic research. However, if published research is a chore to read, most non-academic readers will not take the time to translate it. Long noun strings, excessive nominalizations, academic jargon, six-line sentences, weak sentence cores (main idea does not appear in the subject and verb of the independent clause), absence of sentence agents (who is doing what to whom or what) and more are common in research articles. The practicing technical communicators who responded to our survey said overwhelmingly that this abstruse writing style contributed to their negative views of academic research.

An inaccessible writing style is a key reason why practitioners often feel that academic research is not written for them. Tom Johnson (2010), a prominent practitioner voice in the field, spoke to this problem on his blog, “I’d Rather Be Writing”:

I haven’t said much about the readability of academic research. Mainly, I find the academic’s focus on rhetoric to be one of the great ironies of academia. Rhetoric, so frequently emphasized in academic settings, is the art of fitting the message to the audience. Supposing the academic’s audience is the practitioner, does the way academics deliver their information—with academic jargon, endless explanations of methodology, and prose that strips out all sense of humanity—show any principles of rhetoric? Since academics do understand rhetoric, I can only assume they are crafting their message correctly for their audience. That audience is other academics, not practitioners.

While many academic researchers have called for more applied research focused on improving practice and for more collaboration with practitioners in defining research needs and questions (see, e.g., Albers, 2016; Blakeslee & Spilka, 2004; Rude, 2015), few researchers have addressed the need for research to be written in a writing style that is more inclusive of non-academic readers. Yet this was the number one suggested change to how research is reported offered by our survey respondents.

Given that refereed journals in the field aim to be relevant to readers working in both industry and academia, we urge the journals to address writing style in their submission guidelines and to encourage reviewers to provide feedback on writing style in later stages of the review process. The submission guidelines for Technical Communication have addressed writing style for some time:

The purpose of Technical Communication is to inform, not impress. Write in a clear, informal style, avoiding jargon and acronyms. Use the first person and active voice. Avoid language that might be considered sexist, and write with the journal’s international audience in mind.

The Journal of Technical Writing and Communication also asks authors to “write in clear, concise, coherent prose, using active voice whenever possible.” To better enforce writing style expectations, journals might consider expanding on these expectations in submission guidelines, pointing authors to helpful resources, and emphasizing how a clear, accessible writing style can expand the reach and impact of the research.

Two particularly helpful resources that journals might point to include the Federal plain language guidelines, published on plainlanguage.gov, and The Global English Style Guide by John R. Kohl (2008). Plain language is a movement for clear communication that emphasizes clear writing, structure, and design. Its rich history spans various business, government, and public sectors, including technical communication activities within those sectors; Schriver (2017) extensively documents this history in her award-winning article, “Plain Language in the US Gains Momentum: 1940-2015.” Although plain language has evolved to focus on whole-text communications, on how all aspects of communication design shape findability, comprehension, and usability, it continues to focus as well on clear writing; the Federal plain language guidelines describe numerous strategies for writing clear, concise, and conversational sentences. The Global English Style Guide, with its focus on writing texts for global audiences, also offers authors a plethora of strategies for revising sentences, with special attention given to grammatical constructions, terminology issues, and explicit sentence structures. Each strategy is accompanied by explanations and examples. Because some strategies are more appropriate for writing technical documentation than for writing research articles, journals might identify strategies that align with the needs of their global readers and integrate those directly into submission guidelines.