By Brian C. Britt and Rebecca K. Britt

ABSTRACT

Purpose: This study investigates the role of need for cognition and narrative believability when using a mobile device to take a guided tour of a new location, informing future research and practice in both narrative design and media ecology.

Method: Experiment participants (n = 141) toured a new research facility using one of three combinations of navigation aids (a smartphone only, a brochure and a smartphone, or a brochure only) as a guide. An ordinal regression analysis and multivariate regression analysis were used to assess the relationships among navigation aids, narrative believability, need for cognition, and perceived ease of navigation.

Results: Use of a smartphone only or a brochure in tandem with a smartphone were positively related to evaluations of the narrative as highly consistent as well as perceptions that the narrative offered a high degree of coverage. However, using a brochure in tandem with a smartphone was negatively related to perceived ease of navigation, while narrative plausibility had a positive effect on perceived ease of navigation.

Conclusion: This study illustrates how different mobile devices result in a range of interpretations of the same materials and, ultimately, different levels of success in real-world navigation. Even a simple narrative can aid wayfinding if users find it sufficiently plausible. More broadly, the results suggest the need for research to facilitate the development of more engaging multimedia tour guides.

Keywords: narrative believability, need for cognition, NBS-12, mobile media, guided mobile tour

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Mobile tour guides that emphasize a highly plausible narrative—even a fictional one—may enhance engagement with the tour and help users to more easily navigate the physical space.

- Providing more information or multiple sources of information may enhance appreciation of a narrative but cause users to experience navigational difficulty.

- Self-directed tours should employ a single, well-designed navigation aid rather than multiple devices that only compete with one another for participants’ attention.

The use of mobile technologies to navigate physical locations including museums, cultural exhibits, research facilities and other locales has expanded in recent years (Cho & Park, 2014; Crider & Anderson, 2019; Humphreys & Liao, 2011; Kim, Seo, Yoo, & Ko, 2016; Van Winkle & Lagay, 2012). Often, audio/video tours tell stories in which a virtual narrator leads the way through a narrative, which may be either true or fictionalized, rather than merely providing factual information about the sites being visited and directions to reach subsequent landmarks. Such narratives provide a greater sense of logic and clarity to tour participants’ efforts to traverse a given physical location, with the media and their content offering an organizing mechanism for their understanding of the tangible space and their experience in navigating it (see Oppegaard & Grigar, 2014, for a discussion of intermediality connecting media content with the sensations and interactions within the physical space itself). Thus, narratives allow users to understand the physical space on a deeper level and facilitate smoother, more satisfying navigation (Dow et al., 2005; Garau, 2014) as well as a more meaningful experience (Hunter, 2016). Technical communication theories and techniques may help to enhance such experiences, particularly since scholars are already engaging in related tasks, such as generating new theories and applying those theories to the development of software and other tools that serve specific user needs (Conway, Oppegaard, & Hayes, 2020), analyzing the presentation of technical content in web interfaces (Walwema, 2020), and studying the use of language in tour-related signage (Towner, 2019), thus putting technical communication theories directly into practice.

Narrative-based guided mobile tours must address two otherwise unconnected goals. First, they must provide navigational information in a manner that participants can understand, recall, and replicate through their own behaviors in the environment, thus allowing them to traverse the physical space in the intended fashion. In other words, the content of a guided mobile tour must be carefully crafted so that users can apply the information provided therein towards accurate tour navigation (Chen, 2012; Drucker, 2008; Forsberg, Höök, & Svensson, 1998; Häkkilä, Rantakari, Virtanen, Colley, & Cheverst, 2016; Mandelbaum, 2012; Rizvic, 2011; Sun, Tang, Ye, & Zhu, 2015).

Second, the narratives provided in such guided mobile tours must be sufficiently engaging that they maintain tour participants’ interest and therefore serve a complementary role rather than detracting from the overarching tour experience. In so doing, the communicative framework of the narrative, as it is situated within appropriately selected media, provides a clear organizing scheme for the guided tour itself. Without such a structure, users could lose interest in the story, become confused, and feel a decline of agency (Dow et al., 2005; Van Winkle & Lagay, 2012). As such, the extent to which users perceive the narrative to be believable is of paramount importance, as a narrative that tour participants do not deem believable may detract from the perceived legitimacy of the tour, distract them from the tour directions rather than augmenting their understanding and engagement, and ultimately inhibit their navigation.

To further understand the influence of narratives on guided mobile tours, we must also account for cognitive factors that may affect navigation and engagement with narratives. Need for cognition (NFC), a commonly used variable in assessing persuasion outcomes from narrative messages (Owen & Riggs, 2012; Rosenbaum & Johnson, 2016), is largely concerned with an individual’s tendency to expend cognitive effort. This construct is closely related to the elaboration likelihood model (ELM), as individuals with greater NFC tend to engage with the central route of message processing to a greater degree, focusing more on systematic evaluations of factual information and evidence, than with the peripheral route in which heuristics and general impressions take precedence (Petty & Cacioppo, 1981). In the context of a guided mobile tour, the degree of thought that a user is inclined to devote to the narrative may influence perceptions of its believability. This, in turn, may affect the extent to which the user learns the pattern of behaviors—the directions—necessary to traverse the physical space in the intended sequence (Bandura, 1986), ultimately influencing the navigation experience.

To the authors’ knowledge, no prior research has examined the potential relationships between NFC, narrative believability, and perceived ease of navigation in a self-guided tour context. As such, this study assesses the relationships among these three constructs to demonstrate how technical communicators designing tour narratives can apply NFC and narrative believability to improve tour outcomes. This is particularly relevant as mobile devices are increasingly used, developed, and influenced by technical communicators with careful attention to their content, information, design, and structure. The current study uses an exploratory approach to assess the relationships between NFC, narrative believability, and perceived ease of navigation in the context of a guided mobile tour, thereby illustrating their importance for technical communicators designing tour narratives. More directly, this study demonstrates the potential application of these theories to real-world technical communication in the context of mobile tours, thereby presenting a unique opportunity for practitioners to utilize these theoretical connections in novel ways.

STUDY FRAMEWORK

As the array of personal communication devices has proliferated in recent years, the principles of computer-mediated communication (CMC) have increasingly been applied beyond traditional computers alone (Carr, 2020). Consequently, identifying and utilizing theories in ways that account for the affordances and constraints of different technological devices—that is, the tangible properties of an object that enable or inhibit potential uses—is crucial. To that end, in this exploratory study, we look to the constructs of NFC and narrative believability within the long-established framework of social cognitive theory to inform the theoretical processes and practices of technical communication.

Need for Cognition

Cohen, Stotland, and Wolfe (1955) defined NFC as “a need to structure relevant information in meaningful, integrated ways. It is a need to understand and make reasonable the experiential world” (p. 291). In essence, NFC refers to an individual’s general cognitive motivation toward in-depth thought—following the central processing route of the elaboration likelihood model—which itself is related to curiosity and the need to experience situations in meaningful ways. Of course, individuals may bring other intrinsic motivations to tour experiences (e.g., Kim, Ahn, & Chung, 2013, who found that perceived enjoyment—one possible intrinsic motivation—affected intent to use ubiquitous tour information services via a mobile device), but NFC is especially important in narrative-based mobile tour contexts, as individuals who are more motivated to broadly pursue intellectual stimulation may likewise be more inclined to engage with narratives. A longstanding body of scholarship has found a positive relationship between high levels of NFC, a greater need to evaluate the quality of messages, and the desire to read (Cacioppo, Petty & Morris, 1983; Thompson & Haddock, 2012; Williams-Piehota, Pizarro, Silvera, Mowad, & Salovey, 2006), all of which highlight the wide-ranging importance of NFC throughout one’s engagement with a mobile tour.

Social Cognitive Theory

To address the role of navigation in the current study, social cognitive theory (SCT; Bandura, 1986) provides a framework that, alongside NFC, helps to explain behaviors associated with a guided mobile tour. SCT explains learned behavior in terms of environmental factors (physically external factors such as the environment where one is located), individual self-efficacy (the confidence one has in performing a behavior) and reciprocal determinism (the mutual influence between a person’s behavior and the environment in which the behavior is enacted). Past research has found a strong relationship between NFC, self-efficacy, and learning in explaining actual outcome success (Elias & Loomis, 2002). In the domain of technical communication, SCT has informed the development of an e-health competency scale to inform health interventions (Britt & Hatten, 2016), and social cognitive effects have likewise been used pedagogically in the design and piloting of technical communication courses for software engineers (Mirel & Olsen, 1998), among other such contributions.

In the context of a guided mobile tour, the elements of SCT are intrinsic to the activity. In simpler terms, the environmental factors that are important for SCT are part and parcel of the tour environment in the sense that there could be no tour in the absence of the environment. A tour participant who perceives oneself to be effectively navigating the tour may consequently build his or her self-efficacy and gain sufficient confidence to enact learned behaviors as the tour progresses (see Bandura, 2009; Christy et al., 2017) such that individual differences between tour participants, narrative structures, and tour delivery mechanisms may impact perceived ease of navigation, which could in turn influence self-efficacy as a potential secondary outcome. Lastly, the act of navigating the physical environment via the tour directions, learning more about the physical space and progressing through the tour narrative as a result, is emblematic of the reciprocal determinism that Bandura (1986) describes.

Narratives

Perhaps the preeminent feature of a narrative is its potential for persuasive impact, particularly in the context of a mobile tour where the narrative directly affects real-world beliefs and behaviors because it serves as a navigational aid. Green and Brock (2000), for instance, showed that when a person is absorbed or “transported” into a narrative, that narrative has the capacity to influence the individual’s behaviors to more closely align with the story being told. In much the same vein, Busselle and Bilandzic (2008) found that narratives affect phenomenological experiences and subsequent action regardless of whether a narrative is fictional, but violations of external realism and narrative realism that signify a misalignment with external reality or a lack of internal consistency disrupt the construction of mental models to represent and comprehend the narrative, lessening its persuasive power.

At their core, narratives are ubiquitous in human interactions, have existed throughout humankind as a way to experience life, and are thought to be a fundamental part of the self (Bruni & Baceviciute, 2014; Goodson & Gill, 2011). Narratives are a part of daily life; reading books, watching movies, and browsing the Internet are all commonplace examples of narrative engagement, each of which may significantly influence our attitudes and beliefs (Bruni & Baceviciute, 2014; Green & Brock, 2000) with effects that often persist long after initial exposure (Bal & Veltkamp, 2013; Brumi & Baceviciute, 2014). This stands in contrast with, for example, listening to classical music, which lacks a narrative that can influence our beliefs or eventual behaviors.

The Role of Narratives in Navigation

In the context of mobile tours, such narratives, which are carefully crafted to facilitate navigation, have been described as “a vehicle through which the work of the institution gets done” (Burdelski, Kawashima & Yamazaki, 2014, p. 329). In some institutions, such as museums, historical sites, and parks, narratives are often used in face-to-face guided tours or presented on mobile devices as part of a storytelling practice to engage visitors while providing an educational experience (Stephens, 2018).

Navigation, in turn, describes a person’s ability to effectively progress from one location to a desired destination (Kawai & Kashihara, 2010). Navigation is itself an active process that is propelled by internal knowledge of one’s present location and any external conditions in the given environment (Hunter, 2016). For instance, Bandura (1997) argues that when people observe a set of actions (such as the steps necessary to navigate from an origin point to a destination, whether enacted by a third party or provided as directions from a tour guide), they mentally envision themselves replicating the third party’s prior actions and are thus able to perform the same sequence of behaviors themselves or even improvise novel shortcuts (Burles et al., 2020). This is a pattern-oriented approach that influences their subsequent behavior, allowing them to reproduce the steps to which they were exposed even though they were provided with those directions via textual or auditory instructions rather than witnessing their enaction live.

In short, tour participants draw upon the step-by-step instructions provided by others to learn sequences of behaviors that will allow them to effectively navigate the physical space, then enact those behaviors themselves to reinforce their understanding of the environment and how they can traverse it, ultimately translating the directions received as indirect “observations” into navigational proficiency. Although the patterns of behaviors are provided in the form of directions that tour participants must mentally construct rather than firsthand observations that they directly witnessed, the fundamental logic underlying their learning and navigation remains the same as in the original conception of SCT.

Prior research has addressed narration and narrative design in technical communication, although much of this research is dated, such as Barton and Barton’s (1988) argument that the importance of narration should be conveyed in the classroom, Blyler’s (1996) examination of narrative theory in postmodernist ethnographic research, and Perkins and Blyler’s (1999) text addressing the role of narrative in several key communication contexts. These older studies, alongside a few more recent counterparts (e.g., Lemanski, 2014, which mostly explored Web sites and other professionally oriented virtual communication), primarily focus on the role of narratives in corporate and pedagogical communication rather than technical communication design itself. As such, the current study provides an essential starting point that connects narrative research with communication design.

In broaching this connection, let us start with the construct of ease of navigation. We may conceptualize ease of navigation as the extent to which an individual is able to progress toward specified destinations without experiencing confusion, uncertainty, or outright navigational errors, which is naturally a core objective of guided mobile tours. For instance, Damala, Cubaud, Bationo, Houlier, and Marchal (2008) developed a mobile tour guide with augmented reality components, and they found that tour participants using the device reported reasonably good ease of navigation despite experiencing significant challenges in handling the device itself. Broadly speaking, the perception that one is effectively navigating a physical space—which we may describe as perceived ease of navigation—could increase those individuals’ self-efficacy, helping them to make more confident navigational decisions throughout their engagement with that physical space as well as other unfamiliar venues they may encounter in the future.

With that in mind, mobile devices are popular means to direct tours, using audio, video, and textual information to lead participants through museums, universities, churches, cultural exhibits, and ports, among other locales and events of interest (Cormier, 2009; Sanz-Blas & Buzova, 2016). Studies in navigation and guided tours have explored how mobile devices can aid the navigation process (Cuddihy & Spyridakis, 2012; Laxman, 2011; Sung & Mayer, 2012), although most of the research that refers to “navigation” focuses on the usability of multimedia devices as opposed to successfully traversing a physical space or the perception of doing so. Device usability—that is, the user’s ability to work within the affordances and constraints of a device to obtain desired information, move between content sections, and otherwise access material, regardless of any impact beyond the boundaries of the device itself—is certainly important in its own right. However, in the context of a guided mobile tour, usability is best seen as a means to an end, with that end being satisfactory movement through a physical space between intermediate destinations or toward a desired end location.

In some settings, mobile devices have simply replaced traditional audio tour guides, which typically included a cassette tape or other handheld device that provided recorded spoken commentary. A few tours following this tradition leverage technological affordances to offer additional features—for instance, Kountouris and Sakkopoulos (2018) developed an app that programmatically selects tour stops based on users’ individual preferences, thereby providing a customized tour—but the core logic of using the device to simply offer navigational directions and information about each stop remains the same.

Increasingly, however, multimedia tours tell a story, with a pre-recorded virtual tour guide providing a narrative to make the experience more compelling (Zwarun & Hall, 2012; Dow et al., 2005). Such narratives may be invaluable to the tour experience. As Kamarainen, Reilly, Metcalf, Grotzer, and Dede (2018) observed, among other benefits, the affordances of modern communication technologies allow tour designers to incorporate elements such as “creative narratives … that engage learners in new and unexpected ways” (p. 264). In short, although modern communication technologies present significant constraints that are not exhibited through face-to-face interaction and other modalities (e.g., the absence of sensory cues such as interpersonal physical presence and tactile sensations, the lack of feedback mechanisms that a live tour guide might offer when relying upon static textual or multimedia information, etc.), their capabilities may nonetheless allow technical communicators to design narratives to greatly improve the tour experience.

However, research to date has not explored the impact of the believability of such narratives on an individual’s ability to navigate an unfamiliar territory. This is a key gap in the literature, as knowing what specific narrative elements have the greatest impact on navigation would help tour designers to craft more effective, engaging narratives to address their users’ needs across myriad user groups and contexts. For instance, if a tour participant deems the narrative highly believable, that may engender a heightened focus on its entertainment and informational elements alike and, consequently, greater success at applying directions to traverse the physical space. At minimum, those who are preoccupied with the tour narrative may be less inclined to dwell on navigational failures and perceive their efforts to be more successful. In this way, narrative believability may be intrinsically related to perceived ease of navigation.

Pennington and Hastie (1991) outlined several key components that jointly “determine acceptability of a story, and the resulting level of confidence in the story” (p. 527), representing the overarching construct of narrative believability. These components were initially used in the context of jury trials to assess how believable jurors would deem witness testimony, but they may similarly be applied to a fictional narrative of uncertain veracity presented to tour participants in the hope that they will engage with and commit themselves to the narrative.

The first such component, coverage, refers to “the extent to which the story accounts for evidence presented at trial” (pp. 527-528), or in the case of a guided mobile tour, evidence presented within the narrative that may connect with the physical locations experienced as part of the tour. Next, consistency is “the perception that the facts of a story are not at odds internally or with other information believed…to be true” (Yale, 2013, p. 580). Plausibility, in turn, signifies “the perception that a story is similar to what typically happens in the world” (p. 580), while completeness describes “the extent to which a story conforms to expectations about story structure” (p. 580).

Pennington and Hastie (1991) also described uniqueness as a key element related to juror confidence, as a story that is wildly different from others presented in a jury trial is less likely to be believed, but this does not necessarily describe the believability of a narrative in and of itself—and, as Yale (2013) pointed out, would limit the narrative believability construct to trial contexts alone—so it is excluded from the explication of narrative believability, which instead encompasses narrative coverage, consistency, plausibility, and completeness. Moreover, although all four of these elements are essential for jury trials in which evaluating factuality is essential, this may not be the case for mobile tours and other contexts in which a narrative does not have to be true to be useful. It is possible, for instance, that users may only require the narrative to reach a minimal threshold of believability, or to address a subset of these elements, in order for them to suspend their disbelief and allow the narrative to augment the wayfinding process.

Considering the prevalence of narratives within mobile tours as well as the potential to strategically craft such narratives to benefit users, it is important to consider the possible relationship between narrative believability and perceived ease of navigation. This is addressed in the following research question:

RQ1. How does the believability of a narrative provided via a mobile device affect a person’s perceived ease of navigating a tour in an unfamiliar territory?

Media Ecology

Similarly, if the narrative expressed through a mobile device may affect perceived ease of navigation, it stands to reason that the specific mobile device through which the narrative is communicated may also have an effect, with some devices facilitating navigation more effectively than others. As the core tenets of media ecology theory (Strate, 2004) indicate, the media with which individuals engage provide a conceptual grounding for their experiences across dedicated tasks and, indeed, throughout their day-to-day lives. Other studies demonstrate the importance of navigation aids for users to construct mental maps of their environment—as well as the potential differences between navigation aids using different media—such as Ishikawa, Fujiwara, Imai, and Okabe’s (2008) landmark finding that an electronic device “affects the user’s wayfinding behavior and spatial understanding differently than do the maps and direct experience” (p. 80).

McLuhan’s (1964) classic adage, “the medium is the message” (p. 9), is especially salient in this study, as the particular media used to convey navigational information affect how users perceive, understand, and ultimately apply that information, even if the content itself does not change. More specifically, just as the elements of the narrative itself might influence users’ perceived ease of navigation, the media through which the narrative is communicated may exert a similar effect, helping to shape perceptions of users’ own navigational experiences. After all, “you can do some things on some media that you cannot do on others” (McLuhan, 2003, p. 271) based on their distinct affordances and constraints—or as Strate (2008) more generally argued, “It is the symbolic form [of a message] that is most significant, not the content” (p. 130)—which implies that the same content delivered via different media may affect users in different ways. In particular, as Ong (1967) might suggest based upon the contrast he drew between alphabetic documents and the “sensorium” of electronic communication, media that feature only visual information may be perceived and used differently than multimedia channels providing visual and aural information alike, irrespective of their content.

With that in mind, users of electronic devices with multimedia capabilities may be more readily able to apply navigational directions; alternatively, those relying on a traditional printed document may perceive greater ease of navigation due to the ability to rapidly reference content without grappling with video progress bars and other media elements. Likewise, tour participants using multiple navigation aids may be able to leverage them to compensate for one another’s shortcomings such that the users effectively “buttress one medium with another” as McLuhan (2003, p. 271) suggested, or they may instead find that juggling multiple navigation aids is unduly difficult. In short, while it is likely that the mobile devices on which tour participants rely affect their ease of navigation, the specific manifestation of that effect is uncertain. This leads to the following research question:

RQ2. How do different mobile devices used to navigate a tour in an unfamiliar territory affect perceived ease of navigation?

Additionally, narratives are an important resource that can help to satisfy individuals’ NFC, with those narratives in turn shaping users’ subsequent thoughts and actions. For instance, Owen and Riggs (2012) found that NFC influences narrative transportation, which in turn affects enjoyment of the narrative; Rosenbaum and Johnson (2016) concluded that individuals with higher NFC derived greater enjoyment from narratives whose conclusions had not been “spoiled”; and Zwarun and Hall (2012) showed that, when viewing a narrative, individuals with higher NFC experienced a greater effect on their beliefs and behavioral intentions, with those beliefs and intentions increasingly aligning with those of the narrative.

Given the growing role of multimedia communication today, the question of how individuals immerse themselves in a narrative is critical. In exploring an unfamiliar physical setting, for instance, some individuals will naturally engage with the experience of a guided mobile tour to a different degree than others. In short, NFC is directly related to some of the underlying cognitive antecedents of successful navigation.

In the current study, participants used a mobile device to navigate from the beginning to the end of a guided tour. As such, a central concern is whether individuals’ perceptions of a narrative—in short, narrative believability—is influenced by their NFC, a factor that we would expect to directly impact their information-seeking behaviors. We therefore propose the third research question:

RQ3. How does need for cognition affect perceptions of narrative believability?

In a similar fashion as RQ2, the specific medium through which a narrative is communicated—in other words, the mobile device that an individual is given to assist with navigation—may influence perceptions of the narrative. This prompts the fourth and final research question:

RQ4. How do different mobile devices used to navigate a tour in an unfamiliar territory affect perceptions of narrative believability?

METHODS

Research Design

To properly address how NFC and narrative believability are related to navigation in the context of guided mobile tours, a new research tour was used as a site for study.

The Discovery Park Ubitour was designed to educate visitors about the site’s facilities, using a “scavenger hunt” format to guide visitors at the research park, which is open to the public. For instance, throughout the research facilities, there is a diverse array of landmarks that are of interest to both researchers and the general public, including prominent fountains, glass barriers through which visitors can observe lab experiments, paintings, a Lego sculpture, and a café, among other features. The research infrastructure itself is primarily geared toward healthcare delivery, nanotechnology, and biosciences.

Visitors can take the tour by following printed signs posted throughout each building, which are numbered and marked with QR codes. Those who scan the QR codes with a mobile device can have a pre-recorded narrator provide audiovisual guidance. Alternatively, physical booklets provide the same information.

Materials

One set of materials was created for the tour, which participants were able to view via a mobile device or printed brochure. On the smartphone, the narrative was delivered via a recording of the tour guide. In the brochure, the narrative was delivered as a written transcript. The content shown on the two devices was identical, including the same narrative script and navigational instructions, with the only difference being the presentation format. The materials were created by a research team unaffiliated with the authors for the purposes of providing learning experiences for visitors about the research facilities. The guided tour itself was driven by a simple narrative that was described in the materials as a scavenger hunt, as detailed below. Notably, as suggested by Frith (2015), GPS-based mobile maps were not provided to participants in any of the study conditions, as prior research indicates that such devices are “too usable, such that navigators are depending on them to the detriment of their geographic knowledge and orientation skills” (Waters & Winter, 2011, p. 103; see also Ishikawa et al., 2008).

Narrative within the Materials

The narrative within the tour materials was designed to align with the overarching mission of introducing the public to the facilities and educating those visitors about the site, maintaining an appropriate level of sophistication for the laypersons completing the tour. This narrative aligns with and gives meaning to the physical space that tour participants seek to navigate. As a representative example, the fictional narrative was introduced using the following (with identifying information redacted):

Here’s what happened: Back in the second week of my job as a holographic tour guide, I was floating by one of these tables here at the Burton Morgan coffee shop, trying to brainstorm ideas for a memorable tour, when out of the corner of my eye I saw a piece of paper glide under my table. I picked it up, and immediately asked around to find out who might have dropped it. This person was apparently moving fast, because no one around me could tell me much. I hadn’t been at Discovery Park long, but I knew enough to realize this insignificant-seeming paper could be a vital link in the chain toward solving an important social problem, such as finding a cure for cancer. So I put the tour brainstorming on hold for the day and decided I needed to play Sherlock Holmes instead. I hadn’t been at Discovery Park long, but I knew that important projects went on here. What if this person was working on things that were confidential? So I decided to keep my real mission on the down-low, which meant going undercover. Thankfully my role as a tour guide gave me the perfect excuse to ask lots of questions about projects happening here at Discovery Park. I knew it would be a challenge to come up with the right questions that wouldn’t give away my real goal, but I figured I could handle it.

The narrative presented here served two purposes. First, it provided a story to, as Lim and Aylett (2007) put it, “encourage learning so as to create a meaningful tour experience” (p. 1). This introduction described the tour guide’s discovery of a lost piece of paper, which he believed to be important to the research facilities. He indicated that he saw somebody drop the piece of paper and decided to “play detective,” then invited the tour participant to join him in returning the lost paper to its owner—who might have been engaged with a research project as significant as a cure for cancer, suggesting that returning the piece of paper to its owner could have important implications to which the tour guide (and, vicariously, the tour participant) would have thus contributed.

The playful nature of this introduction meant that it avoided “taking itself too seriously,” so to speak, using phrases like “holographic tour guide” to implicitly acknowledge and demonstrate to the viewer that the scenario was fictional. Reducing the apparent gravity of the narrative by clearly portraying it as fictional may have reduced participant anxiety and frustration with any navigational errors made during the tour. Likewise, in the context of the present study, since the fictional nature of the narrative was demonstrated from the beginning, perceptions of its believability could freely vary, as opposed to a nonfiction narrative whose veracity would have been assumed by definition.

The tour also required the visitor to stop at physical locations by following the tour guide’s directions in conjunction with the story. As such, the second purpose of the narrative was to guide the visitor to each stop in the tour. Below is an example of how participants were directed to navigate from one location to the next:

Head out the doors behind you and to your right (my left) and take the first sidewalk right to the MANN building. There, you’ll find marker #4 in front of the paintings of the building’s sponsors, and I’ll tell you if my investigations bore fruit.

While the narrative was offered in extensive detail to allow participants to immerse themselves within it, the navigational directions were provided in a straightforward fashion to maximize their clarity. In addition, details such as “your right (my left),” which are common in real-world tours to contrast tour participants’ perspective with that of the tour guide, tacitly reinforced the believability of the virtual tour guide.

Notably, near the conclusion of the tour, the tour guide recounted returning the lost piece of paper:

As it turned out, the paper didn’t belong to someone who even had an office in Discovery Park, though he had lots of ties with it and was blessedly quite nearby. He was a postdoctoral researcher residing in the biomedical sciences building that you can see to my left, right across from Discovery Park but not in it. He was thrilled to get his task list back, and was kind enough to explain a bit more about his connections to Discovery Park. While he was working on collaborations with researchers in both Bindley and Birck, using, yes, fructose and sucrose. His primary connection had been in the previous two years, when he’d been funded through the Discovery Learning Research Center’s fellowships, first to work with local middle-schoolers and then to take a three-week trip to China the next year.

This conclusion appeared to wrap up the overarching story arc, as the tour guide’s aim was completed: the piece of paper was returned to its rightful owner. However, the tour participant never gained in-depth information about how the “task list” would be used or what tangible benefits stemmed from the tour guide (and, vicariously, the tour participant) returning it. Thus, some tour participants may have perceived this as a perfectly suitable conclusion, while others may have found it to be an unsatisfying partial explanation of the outcome, yielding divergent perceptions of the narrative’s coverage and completeness. Likewise, while the facts presented within the narrative did not explicitly conflict, the owner of the piece of paper was ultimately found to be a postdoctoral researcher studying nutritional content rather than a scholar seeking a cure for cancer, working with confidential materials, or otherwise engaging in dramatic research whose notoriety would be obvious to lay audiences. Some users may have therefore perceived the conclusion to be inconsistent with the initial assumptions about the owner, so like the other elements of narrative believability, the design of the narrative was such that consistency also could have varied between tour participants.

All told, the narrative elements demonstrated above facilitated sufficient variance in the components of narrative believability to serve the present study while still maintaining a reasonable degree of realism.

Participant Selection

To control for the influences of age, education, and ability to use a mobile device, this study used an undergraduate student sample. Teenagers and young adults are among the biggest groups of users of mobile devices (Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2010) and consequently represent a relatively large portion of overall activity on such devices—hence the targeting of this particular demographic group. Notably, although guided mobile tours have been designed to serve a variety of contexts and demographics (e.g., OnCell, 2020; PocketSights, 2019; Uncubed, 2020), an increasing number are tailored toward undergraduate students as part of class activities and initiatives to familiarize them with college campuses (e.g., GooseChase, 2019, which offers tailored scavenger hunt-based activities and associated licenses for universities and colleges), making this a salient population for an initial examination of these constructs. Thus, upon IRB approval, participants at a large, Midwestern university signed up to be in the study via a university recruitment system, which awarded extra credit towards a course assignment.

Study Conditions

Participants arrived at a lab located on-site at one of the research facilities at the university and were required to read and complete an IRB-approved consent form. Afterward, they toured the research facilities, guided by one or more mobile devices (smartphone, brochure, or smartphone and brochure) that were randomly assigned to them.

The first two conditions were designed to simulate scenarios in which tour participants are given a single navigation aid. The last condition, in turn, represented cases in which multiple redundant forms of the same content are provided. This does not provide tour participants with additional information, but it may be done in practice to allow participants to triangulate different perspectives on the same information, to select the medium that best fits their personal learning style (e.g., some participants might gravitate toward multimedia content that creates a pseudo-interpersonal connection with the virtual tour guide and facilitates greater personal investment in the narrative, while others might prefer a brochure’s affordances that make it easier to rapidly return to key information), or to guard against potential technical difficulties (e.g., if the smartphone fails, the brochure is still usable). As Hirtle (2000) said regarding navigation aids, “redundancy is a positive characteristic, in contrast to other forms of communication where concise, non-redundant communication might be preferred” (p. 34). While such redundancy is generally integrated into a single navigation aid, multiple distinct navigation aids presenting the same information in different ways could potentially achieve the same goal.

Each participant was given the assigned mobile device(s) and directed to complete the tour before returning to the starting point and completing a paper-and-pencil survey.

Demographic data

141 participants completed the tour and associated survey (male = 48.1%, female = 51.2%, declined to disclose = 0.6%). Most participants who self-identified their ethnicities indicated that they were Caucasian (63.6%), with the remainder Asian/Pacific Islander (23.5%), Hispanic/Latino (5.6%), African American (4.9%), or Native American (0.6%). There was a relatively even split among freshman (30.2%), juniors (26.5%), and seniors (27.2%), with sophomores (15.4%) and one graduate student (0.6%) comprising the remainder of the sample.

Measures

Perceived ease of navigation

The extent to which individuals felt that they were able to easily navigate the physical space in accordance with the tour directions was assessed using a single-item ordinal-level measure, “Overall, how much trouble did you have finding your way from stop to stop?” with response options of “A lot of trouble,” “Some trouble,” “No trouble,” and “I do not know.”

Need for cognition: NFC

The need for cognition (NFC) scale, which has previously been observed to be valid (Cacioppo, Petty & Kao, 1984), assesses the tendency to engage and enjoy in cognitive efforts. All 18 items from the original scale were included in the present study and are provided in the Appendix.

Narrative believability: NBS-12

Yale (2013) developed the 12-item Narrative Believability Scale (NBS-12; see Appendix) to measure the extent to which one perceives a narrative to be believable based upon four attributes: its plausibility, completeness, consistency and coverage. In describing the NBS-12, Yale (2013) states that, “It is important to recognize the goal of the instrument is not to measure perceived truth, but rather to measure the various qualities that a seemingly true story has (i.e., its believability)” (p. 4). In other words, the NBS-12 focuses on attitudes about various aspects of a given narrative rather than the simple binary belief about whether or not the narrative is true. Crucially, although the scale was originally developed for the evaluation of legal narratives in court cases, its grounding in attitudes allows it to be used even on narratives that are obviously fictional—such as that of the mobile tour in this study—as this measure effectively assesses whether the narrative is believable enough for an individual to willingly suspend disbelief and treat the story as truthful rather than whether or not the person is merely aware of its inherent truth or falsehood.

Analytic Procedure

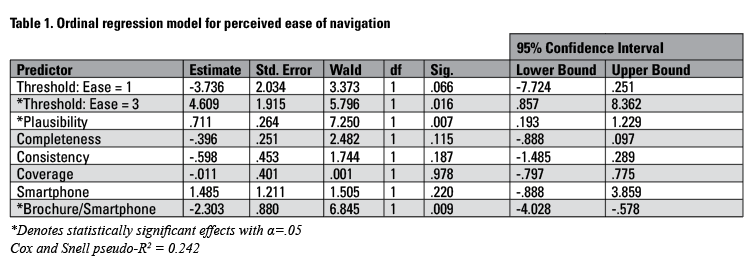

To evaluate RQ1-2, an ordinal regression analysis was conducted on the effect of plausibility, completeness, consistency, and coverage, as well as the effect of using a smartphone alone or a brochure and smartphone together rather than a brochure alone, on an individual’s perceived ease of navigating the tour. Ordinal regression was employed in this case since the dependent variable, perceived ease of navigation, was measured on the ordinal level.

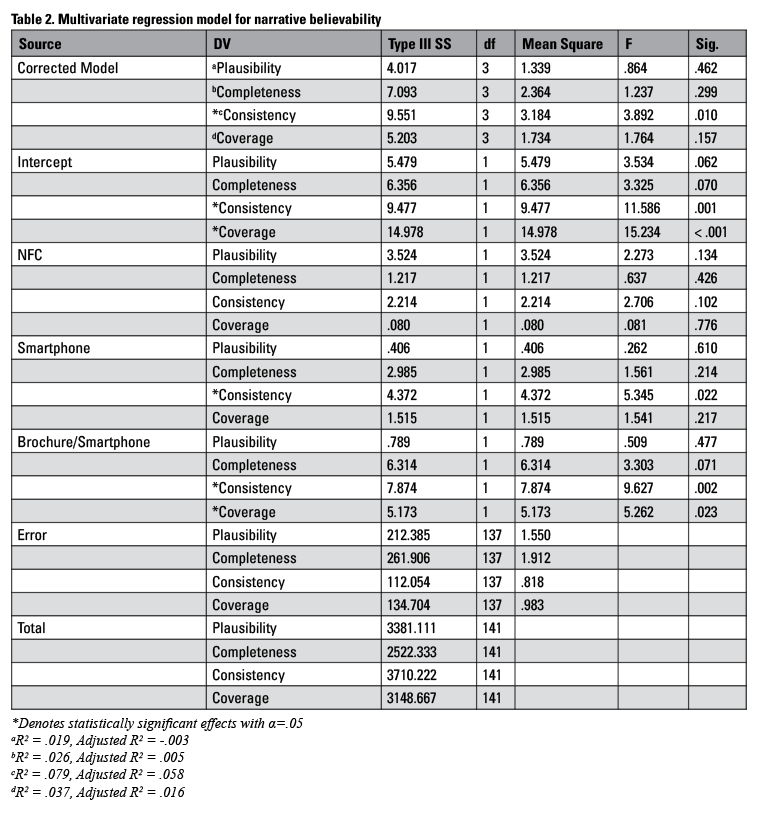

RQ3-4 were assessed using a multivariate regression analysis to determine the effect of an individual’s NFC, and whether they used a smartphone or a brochure and smartphone rather than a brochure alone, on the perceived plausibility, completeness, consistency, and coverage of the tour narrative based upon responses to the NBS-12.

All research questions were evaluated using α = .05. Due to the exploratory nature of the two analyses, further steps to control the experimentwise Type I error rate (e.g., Bonferroni correction) would have been inappropriate (see Armstrong, 2014, p. 505; Bender & Lange, 2001, p. 344).

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics NFC

The mean and standard deviation for the overall NFC scale in the current study were M = 3.29 and SD = .511, respectively, with a Cronbach’s alpha value of α = .698, suggesting borderline reliability for the scale in the present study.

NBS-12

Because the NBS-12 has been largely untested since its initial validation, Cronbach’s alpha scores were used to assess the reliability for each of its four subscales within the current context. The plausibility subscale held α = 0.803 (M = 4.758, SD = 1.236), completeness yielded α = 0.812 (M = 4.002, SD = 1.380), consistency had α = 0.721 (M = 5.009, SD = 0.937), and coverage gave α = 0.777 (M = 4.620, SD = 1.002). All Cronbach’s alpha values adhered to the commonly accepted reliability threshold of α ≥ 0.700 (Nunnally, 1978), indicating that the NBS-12 and its subscales were reliable in the present study.

Research Questions

For RQ1, plausibility (p = 0.007, β = 0.711) was found to play a statistically significant role in the ordinal regression analysis (Table 1), yielding a positive effect on perceived ease of navigation. Completeness (p = 0.115), consistency (p = 0.187), and coverage (p = 0.978) were not statistically significant predictors of perceived ease of navigation.

For RQ2, using a brochure and smartphone in tandem (p = 0.009, β = -2.303) had a negative effect on perceived ease of navigation. On the other hand, no statistically significant difference was found between using a smartphone alone and using another device as a navigation aid (p = 0.220).

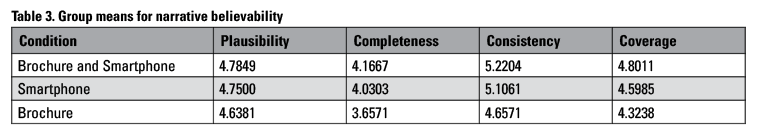

For RQ3, NFC was not a statistically significant predictor of any of the four narrative believability components in the multivariate regression analysis (p = 0.102 to 0.776; see Table 2). In addressing RQ4, use of a smartphone alone resulted in heightened perceptions of the tour narrative as being consistent (p = 0.022, SS = 4.372), while participants who used a brochure and smartphone together tended to perceive the tour narrative to have stronger consistency (p = 0.002, SS = 7.874) and coverage (p = 0.023, SS = 5.173) alike. As shown in Table 3, subjects in the brochure and smartphone condition had the highest group mean for all four narrative believability components (plausibility: brochure and smartphone condition = 4.7849, other conditions = 4.6381 to 4.7500; completeness: brochure and smartphone condition = 4.1667, other conditions = 3.6571 to 4.0303; consistency: brochure and smartphone condition = 5.2204, other conditions = 4.6571 to 5.1061; coverage: brochure and smartphone condition = 4.8011, other conditions = 4.3238 to 4.5985), while the smartphone-only condition exhibited a mean consistency rating (5.1061) that was far closer to that for the brochure and smartphone condition (5.2204) than the brochure-only condition (4.6571).

For RQ3, NFC was not a statistically significant predictor of any of the four narrative believability components in the multivariate regression analysis (p = 0.102 to 0.776; see Table 2). In addressing RQ4, use of a smartphone alone resulted in heightened perceptions of the tour narrative as being consistent (p = 0.022, SS = 4.372), while participants who used a brochure and smartphone together tended to perceive the tour narrative to have stronger consistency (p = 0.002, SS = 7.874) and coverage (p = 0.023, SS = 5.173) alike. As shown in Table 3, subjects in the brochure and smartphone condition had the highest group mean for all four narrative believability components (plausibility: brochure and smartphone condition = 4.7849, other conditions = 4.6381 to 4.7500; completeness: brochure and smartphone condition = 4.1667, other conditions = 3.6571 to 4.0303; consistency: brochure and smartphone condition = 5.2204, other conditions = 4.6571 to 5.1061; coverage: brochure and smartphone condition = 4.8011, other conditions = 4.3238 to 4.5985), while the smartphone-only condition exhibited a mean consistency rating (5.1061) that was far closer to that for the brochure and smartphone condition (5.2204) than the brochure-only condition (4.6571).

DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

This study served the key purpose of examining the role of narrative believability and NFC in the context of a guided mobile tour. The NBS-12 was used to assess narrative believability for purposes outside the context for which it was originally developed, which included implications for persuasion and juror decision making processes (Yale, 2013). This was an ideal scale for the current study due to its subscales that assessed plausibility, completeness, consistency, and coverage. These factors are crucial to assessing the believability or persuasiveness of a narrative, which, in the context of a guided mobile tour, shared important theoretical linkages with perceived ease of navigation, particularly since narratives have been found to be important resources for individuals who tend to be stimulated by deeper thought processes (e.g., Rosenbaum & Johnson, 2016; Zwarun & Hall, 2012).

With that in mind, the present manuscript replicated the moderate reliability for the subscales of the NBS-12 despite its use with an entirely different population within a new set of circumstances. It is useful to observe the effectiveness of this measure beyond merely predicting the outcomes of legal proceedings, as this helps to indicate its broader utility as a scale for the construct of interest: narrative believability.

While the plausibility of the narrative was significantly related to perceived ease of navigation as assessed via RQ1, the other NBS-12 subscales of completeness, consistency, and coverage were not significant predictors. This indicates, rather curiously, that the extent to which the story in the narrative was perceived as being complete in its own right, its apparent internal consistency, and the degree to which it fully covered the topic at hand had no discernible effect on perceived ease of navigation. This defies conventional wisdom that “more information is better,” suggesting that navigation aids may be better used to highlight key points and allowing users to fill in the gaps between them rather than to paint an absolutely comprehensive or even internally consistent story related to their surroundings.

It should be noted that the detective-like narrative framework used in this study was not particularly novel in nature, with little aside from the “holographic” nature of the tour guide setting this narrative apart from other scavenger hunt scenarios. One might even argue that this narrative was childish, featuring a simplistic narrative thread without significant plot twists to captivate the user. Yet as this study demonstrates, even a generic narrative can motivate people to learn. This is especially true if the narrative, regardless of its sophistication or lack thereof, is deemed plausible—after all, innovative narrative constructs and compelling plot twists are not essential for users to conclude that “this could happen”—as a plausible narrative provides a meaningful cognitive foundation around which users’ engagement with navigational directions may be structured. In short, although this study did not demonstrate that narrative completeness, consistency, or coverage influenced ease of navigation, the effect of plausibility was statistically significant; as such, technical communicators developing navigation aids should prioritize the plausibility of those narratives, even if the storylines they convey are otherwise simplistic.

Different mobile devices resulted in statistically significant effects on perceived ease of navigation and narrative believability, as assessed via RQ2 and RQ4. Specifically, users engaging with the tour narrative via a smartphone alone perceived it to have greater consistency than participants using other navigation aids did. On the other hand, those who were given both a brochure and smartphone reported more difficulty with navigation than their peers, yet they perceived the combination of aids to offer even greater consistency and coverage relative than a single navigation aid.

This latter result is especially interesting, as it demonstrates that allowing users to employ multiple navigation aids that compensate for one another’s weaknesses or can otherwise be triangulated may enhance their appreciation of the narrative, but they suffered greater perceived navigational difficulties as a consequence, so this is not necessarily a viable strategy for improving guided mobile tours. On the contrary, participants who sought to juggle multiple navigation aids tended to struggle as a result, suggesting that more is not necessarily better.

These two consequences of a multiplicity of media ought to be carefully considered. There are significant benefits therein, particularly to enhance narrative engagement on the part of users. In other words, the medium used to communicate a narrative matters, and seemingly redundant media conveying exactly the same information may improve perceptions that the narrative is stable. Yet when those media are meant to be used as aids to perform an external task, compelling users to employ multiple media in tandem may do more harm than good. As for the design of self-directed tours themselves, the lesson is, simply put, that they should employ a single, well-designed navigation aid rather than multiple devices that only compete with one another for participants’ attention.

Earlier research in medium studies suggested that the affordances and constraints of text-oriented, asynchronous attributes in technologies are central attributes (Sproull & Kiesler, 1991); likewise, more recent studies of new media have continued to emphasize the importance of affordances and constraints in communicating information (de Graaf & Meijer, 2019; Meijer, 2008). As this discipline has increasingly highlighted the roles of affordances and constraints, the physical attributes of the brochure and mobile device should be considered in this context. For instance, regarding narrative believability, users employing the brochure and mobile device in tandem deemed the narrative to have greater consistency and coverage than other users engaging with only a single device, yet they reported comparatively worse ease of navigation. The fact that the narrative was available in an asynchronous format in both the brochure and mobile device in a handheld, tangible format may have allowed users to easily cross-reference the two sources and verify that the content was replicated across both sources, increasing perceptions of its reliability and suggesting that the narrative held greater consistency and coverage as a result. In other words, although the content across the two media was wholly redundant, the replication may have lent greater weight to the content in the minds of users.

Finally, as discussed in conjunction with RQ3, the NFC exhibited by tour participants did not have a statistically significant effect on their evaluations of the narrative. This suggests that attempts to satisfy tour participants’ NFC within a guided mobile tour narrative may ultimately be inconsequential, yielding minimal effect on the overall tour experience.

More broadly, it is noteworthy that the ordinal regression model of perceived ease of navigation yielded pseudo-R2 = 0.242, so the predictors explored in this study explained roughly a quarter of the variance in perceived ease of navigation. A great deal of the variance remains unexplained, implying the need for further research into perceived ease of navigation.

These results suggest possible limitations in current multimedia tools used to deliver mobile tours. They also further beg the question: how can we make video tours more engaging without relying on multiple navigation aids and potentially sacrificing navigational efficacy? Future studies and interventions should consider how to use theory to drive the design of and fully engage in the use of mobile technologies to their fullest potential, with a deeper consideration of the role that narratives may play.

Future Directions

Prior research indicates that individuals tend to overestimate their own navigational abilities, although this effect is less pronounced for college-aged individuals than older adults (van der Ham, van der Kuil, & Claessen, 2020). With that said, although perceived ease of navigation is an important construct in its own right with significant psychological ramifications, the observed effects related to perceived ease of navigation do not necessarily imply the same for an individual’s actual ease of navigation. Consequently, it would be valuable for future research to assess actual navigational ease alongside self-perceptions in order to discern whether the effects observed upon perceived ease of navigation also apply to individuals’ tangible experiences therein.

Beyond that, mobile devices used in guided tours often result in different interpretations of the same materials when presented to the user, resulting in differences in the ability to successfully navigate the tour. In this study, the perceived plausibility of the narrative and the device used to deliver that narrative had a significant effect on perceived ease of navigation. As such, future researchers may wish to develop best practices for developing guided mobile tours that make use of plausible narratives.

Relatedly, the present study focused on an educational experience, in which users might expect a degree of narrative realism. In other contexts in which the acquisition of knowledge is less important, plausibility may not be as essential. Researchers should therefore examine a variety of tour contexts, as the nature and purpose of any given tour may moderate the relationships identified in this study.

Moreover, guided tours in general increasingly make use of technologies, and the principles guiding the delivery of tours are interpretive in nature, so it stands to reason that critically examining long held beliefs (e.g., Ham, 2010) about the efficacy of interpretation and the potential long-term effects of narrative engagement would benefit scholarship on mobile media and psychology as well as the development of multimedia applications, among other areas. Therefore, scholarship should continue to explore the role of communication delivered via narratives within a guided tour, recognizing that, as humans are natural storytellers, the optimal method of delivering narratives will likely be specific to the type of tour and goal (Skibins, Powell, & Stern, 2012). Regardless, exploring the role of narrative believability in guided mobile tours and the theoretical frameworks that guide them is crucial to deliver optimal experiences for users today.

Implications

As this study demonstrated, when a narrative is integrated into a guided mobile tour, the plausibility of that narrative is an important determinant of its usefulness. This makes a degree of sense: if a user does not find a narrative to be remotely plausible and thus does not accept its overall storyline, then that story will likely do little to augment the user’s navigational success. Thus, it is important to ensure that the activities of characters and the events that transpire within the narrative are reasonably similar to what one would expect to happen in the real world. This does not necessitate that the narrative be nonfiction; on the contrary, the use of obviously fictional constructs like the “holographic tour guide” in this study are perfectly acceptable, as long as the tour guide behaves in a manner that is otherwise relatively familiar (i.e., what one would expect from a “non-holographic” tour guide). This affords technical communicators significant creative license in developing engaging stories in which their respective audiences may immerse themselves.

On the other hand, the manner in which the narrative handles factual information does not appear to be as essential. In this study, the perception that the narrative had “loose ends” or was otherwise missing important information (coverage) did not have a statistically significant effect on users’ perceived ease of navigation. Likewise, internal inconsistencies and disagreements with other information that the users knew to be true (consistency) did not have a discernible effect, nor did the narrative’s conformity to expectations about story structure (completeness) play a role. Such factors might affect a user’s enjoyment of the narrative, and perhaps of the tour itself, but they did not influence the individual’s perceptions of his or her ease of navigation. This is especially important given that the use of multiple navigation aids does appear to improve perceptions of narrative consistency and coverage but worsens perceptions of the actual navigation process. In short, using multiple media may improve users’ enjoyment of the narrative, but in the context of a guided mobile tour, this is likely not worth the loss of effective navigation (or the perception therein). Thus, in this context, technical communicators should plan for each user to employ a single navigation aid with a sufficiently plausible narrative to augment the wayfinding process. However, in other contexts for which engagement with the environment is not a primary goal, it may be beneficial to provide the same narrative via multiple media, as doing so may enrich the user’s evaluations of the narrative without the downside of harming navigational efficacy.

REFERENCES

Armstrong, R. A. (2014). When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics, 34, 502-508.

Bal, P. M., & Veltkamp, M. (2013). How does fiction reading influence empathy? An experimental investigation on the role of emotional transportation. PLOS One, 8, e55341.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Bandura, A. (2009). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In J. Bryant & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (3rd ed.) (pp. 94-489). New York: Routledge.

Barton, B. F., & Barton, M. S. (1988). Narration in technical communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 2(1), 36-48.

Bender, R., & Lange, S. (2001). Adjusting for multiple testing—when and how? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54, 343-349.

Blyler, N. R. (1996). Narrative and research in professional communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 10(3), 330-351.

Britt, R. K., & Hatten, K. N. (2016). The development and validation of the eHealth competency scale: A measurement of self-efficacy, knowledge, usage, and motivation. Technical Communication Quarterly, 25(2), 137-150.

Bruni, L. E., & Baceviciute, S. (2014). On the embedded cognition of non-verbal narratives. Sign Systems Studies, 42(2/3), 359-375.

Burdelski, M., Kawashima, M., & Yamazaki, K. (2014). Storytelling in guided tours: Practices, engagement, and identity at a Japanese American museum. Narrative Inquiry, 24(2), 328-346.

Burles, F., Liu, I., Hart, C., Murias, K., Graham, S. A., & Iaria, G. (2020). The emergence of cognitive maps for spatial navigation in 7- to 10-year-old children. Child Development, 91(3), e733-e744.

Busselle, R., & Bilandzic, H. (2008). Fictionality and perceived realism in experiencing stories: A model of narrative comprehension and engagement. Communication Theory 18(2), 255-280.

Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., & Kao, C. F. (1984). The efficient assessment of need for cognition. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48, 306-307.

Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., & Morris, K. J. (1983). Effects of need for cognition on message evaluation, recall, and persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 805-818.

Carr, T. C. (2020). CMC is dead, long live CMC!: Situating computer-mediated communication scholarship beyond the digital age. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 25(1), 9-22.

Chen, C. (2012). Context-aware camera planning for interactive storytelling. In E. Banissi & M. Sarfraz (Eds.), Computer Graphics, Imaging and Visualization, Ninth Annual Conference (pp. 43-48). Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE.

Cho, H., & Park, B. (2014). Testing the moderating role of need for cognition in smartphone adoption. Behaviour & Information Technology, 33(7), 704-715.

Christy, K. R., Jensen, J. D., Sarapin, S. H., Yale, R. N., Weaver, J., & Pokharel, M. (2017). Theorizing the impact of targeted narratives: Model admiration and narrative memorability. Journal of Health Communication, 22(5), 433-441.

Cohen, A. R., Stotland, E., & Wolfe, D. M. (1955). An experimental investigation of need for cognition. Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology, 51, 291-294.

Conway, M., Oppegaard, B., & Hayes, T., 2020. Audio description: Making useful maps for blind and visually impaired people. Technical Communication, 67(2), 68-86.

Cormier, K. (2009). Art of audio narrative: Spring 2009. Retrieved from http://www.kencormier.com/artofaudionarrative.htm

Crider, J., & Anderson, K. (2019). Disney death tour. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 23(2). Retrieved from

http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/23.2/topoi/crider-anderson/index.html

Cuddihy, E., & Spryidakis, J. H. (2012). The effect of visual design and placement of intra-article navigation schemes on reading comprehension and website user perceptions. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 1399-1409.

Damala, A., Cubaud, P., Bationo, A., Houlier, P., & Marchal, I. (2008). Bridging the gap between the digital and the physical: Design and evaluation of a mobile augmented reality guide for the museum visit. Proceedings of the Digital Interactive Media in Entertainment and Arts, ACM, NY: 120-127.

de Graaf, G., & Meijer, A. (2019). Social media and value conflicts: An explorative study of the Dutch police. Public Administration Review, 79(1), 82-92. doi: 10.1111/puar.12914

Dow, S., Lee, J., Oezbek, C., MacIntyre, B., Bolter, J. D., & Gandy, M. (2005). Exploring spatial narratives and mixed reality experiences in Oakland cemetery. In Proceedings of the Advances in Computer Entertainment Conference (ACE 2005) (pp. 51-60). New York: ACM.

Drucker, J. (2008). Graphic devices: Narration and navigation. Narrative, 16, 121-139.

Elias, S. M., & Loomis, R. J. (2002). Utilizing need for cognition and perceived self-efficacy to predict academic performance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32, 1687-1702.

Forsberg, M., Höök, K., & Svensson, M. (1998). Design principles for social navigation tools. In Proceedings of the 4th ERCIM Workshop on User Interfaces for All. ERCIM. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.34.9536&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Frith, J. (2015). Smartphones as locative media. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Garau, C. (2014). From territory to smartphone: Smart fruition of cultural heritage for dynamic tourism development. Planning Practice & Research, 29(3), 238-255.

Goodson, I. F., & Gill, S. R. (2011). Narrative Pedagogy: Life History and Learning. New York: Peter Lang.

GooseChase. (2019). University & college scavenger hunts. Retrieved September 4, 2020 from https://www.goosechase.com/solutions/university-college/

Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 701-721.

Häkkilä, J., Rantakari, J., Virtanen, L., Colley, A., Cheverst, K. (2016). Projected fiducial markers for dynamic content display on guided tours. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2490-2496. New York: ACM.

Ham, S. H. (2010). From interpretation to protection: Is there a theoretical basis? Journal of Interpretation Research, 14(2), 49-57.

Hirtle, S. C. (2000). The use of maps, images and “gestures” for navigation. In C. Freksa, C. Habel, W. Brauer, & K. F. Wender (Eds.), Spatial Cognition II (pp. 31-40). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

Humphreys, L., & Liao, T. (2011). Mobile geotagging: Reexamining our interactions with urban space. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication,

16, 407-423.

Hunter, J. E. (2016). Sharing experiences, constructing memories: An ethnographic report of naturalists in the field. Journal of Interpretation Research, 21(1), 37-40.

Ishikawa, T., Fujiwara, H., Imai, O., & Okabe, A. (2008). Wayfinding with a GPS-based mobile navigation system: A comparison with maps and direct experience. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(1), 74-82.

Kamarainen, A., Reilly, J., Metcalf, S., Grotzer, T., & Dede, C. (2018). Using mobile location-based augmented reality to support outdoor learning in undergraduate ecology and environmental science courses. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America, 99(2), 259-276.

Kawai, R., & Kashihara, A. (2010). A cognitive tool for navigational learning and its meta-cognition in hyperspace. In V. Aleven, J. Kay, & J. Mostow (Eds.), Intelligent Tutoring Systems (pp. 389-400). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

Kim, D., Seo, D., Yoo, B., & Ko, H. (2016). Development and evaluation of mobile tour guide using wearable and hand-held devices. In M. Kurosu (Ed.), Human-computer interaction: Novel user experiences (pp. 285-296). Switzerland: Springer.

Kim, J., Ahn, K., & Chung, N. (2013). Examining the factors affecting perceived enjoyment and usage intention of ubiquitous tour information services: A service quality perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 18(6), 598-617.

Kountouris, A., & Sakkopoulos, E. (2018). Survey on intelligent personalized mobile tour guides and a use case walking tour app. In 2018 IEEE 30th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (pp. 663-666). Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE.

Laxman, K. (2011). Dynamic and spatial representations of web movements and navigational patterns through the use of navigational paths as data. Instructional Science, 39, 881-900.

Lemanski, S. (2014, June). Technical storytelling: The power of narrative in digital communication. Intercom, 7-12. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/33352032/Technical_Storytelling_The_Power_of_ Narrative_in_Digital_Communication

Lim, M. Y., & Aylett, R. (2007). Narrative construction in a mobile tour guide. In M. Cavazza & S. Donikian (Eds.), Virtual storytelling: Using virtual reality technologies for storytelling (pp. 1-10). Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Mandelbaum, J. (2012). Storytelling in conversation. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 492-510). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

McLuhan, M. (2003). Understanding Me: Lectures and Interviews (S. McLuhan & D. Staines, Eds.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Meijer, A. J. (2008). E-mail in government: Not post-bureaucratic but late-bureaucratic organizations. Government Information Quarterly, 25(3), 429-447. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2007.05.004

Mirel, B., & Olsen, L. A. (1998). Social and cognitive effects of professional communication on software usability, Technical Communication Quarterly, 7(2), 197-221.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

OnCell. (2020). Clients and mobile tour app examples. Retrieved from https://www.oncell.com/clients/

Ong, W. J. (1967). The presence of the word. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Oppegaard, B., & Grigar, D. (2014). The interrelationships of mobile storytelling: Merging the physical and the digital at a national historic site. In J. Farman (Ed.), The mobile story: Narrative practices with locative technologies (pp. 17-33). New York, NY: Routledge.

Owen, B., & Riggs, M. (2012). Transportation, need for cognition, and affective disposition as factors in enjoyment of film narratives. Scientific Study of Literature, 2(1), 128-149.

Pennington, N., & Hastie, R. (1991). A cognitive theory of juror decision making: The story model. Cardozo Law Review, 13, 519-557.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1981). Attitudes and persuasion: Classic and contemporary approaches. New York: Routledge.

Perkins, J. M., & Blyler, N. (Eds.) (1999). Narrative and professional communication. Stamford, CT: Ablex Publishing.

Pew Internet and American Life Project. (2010). Who uses cell phones? Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Teens-and-Mobile-Phones/Chapter-1/Who-uses-cell-phones.aspx

PocketSights. (2019). Tour builder | Build mobile walking tours. Retrieved from https://pocketsights.com/

Rizvic, S. (2011). Multimedia techniques in virtual museum applications in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In Systems, Signals, and Image Processing (IWSSIP), 18th international conference (pp. 1-4). Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE.

Rosenbaum, J. E., & Johnson, B. K. (2016). Who’s afraid of spoilers? Need for cognition, need for affect, and narrative selection and enjoyment. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5(3), 273-289.

Sanz-Blas, S., & Buzova, D. (2016). Guided tour influence on cruise tourist experience in a port of call: An eWOM and questionnaire-based approach. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18, 558-566.

Skibins, J. C., Powell, R. B., & Stern, M. J. (2012). Exploring empirical support for interpretation’s best practices. Journal of Interpretation Research, 17(1), 25-44.

Sproull, L., & Kiesler, S. (1991). Connections: New Ways of Working in the Networked Organization. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Stephens, S. H. (2018). Using rhetoric to understand audience agency in natural history apps. Technical Communication, 65(3), 280-292.

Strate, L. (2004). A media ecology review. Communication Research Trends, 23(2), 3-48.

Strate, L. (2008). Studying media as media: McLuhan and the media ecology approach. Media Tropes, 1, 127-142.

Sun, F., Tang, X., Ye, T., & Zhu, F. (2015). Thematic atlas information expansion design: A storytelling concept under web environment. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Geoinformatics. IEEE, Los Alamitos, CA.

Sung, E., & Mayer, R. E. (2012). Affective impact of navigational and signaling aids to e-learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 473-483.

Thompson, R. & Haddock, G. (2012). Sometimes stories sell: When are narrative appeals most likely to work? European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 92-102.

Towner, E. B. (2019). Expository warnings in public recreation and tourism spaces. Technical Communication, 66(4), 347-362.

Uncubed. (2020). 9 awesome walking tour apps. Retrieved from https://uncubed.com/daily/9-awesome-walking-tour-apps/

van der Ham, I. J. M., van der Kuil, M. N. A., & Claessen, M. H. G. (2020). Quality of self-reported cognition: Effects of age and gender on spatial navigation self-reports. Aging & Mental Health. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13607863.2020.1742658

Van Winkle, C. M., & Lagay, K. (2012). Learning during tourism: The experience of learning from the tourist’s perspective. Studies in Continuing Education, 34(3), 339-355.

Walwema, J. (2020). A values-driven approach to technical communication. Technical Communication, 67(1), 7-37.

Waters, W., & Winter, S. (2011). A wayfinding aid to increase navigator independence. Journal of Spatial Information Science, 3, 103-122.

Williams-Piehota, P., Pizarro, J., Silvera, S. A., Mowad, L., & Salovey, P. (2006). Need for cognition and message complexity in motivating fruit and vegetable intake among callers to the cancer information service. Health Communication, 19, 75-84.

Yale, R. N. (2013). Measuring narrative believability: Development and validation of the narrative believability scale (NBS-12). Journal of Communication, 63(3), 578-599.

Zwarun, L., & Hall, A. (2012). Narrative persuasion, transportation, and the role of need for cognition in online viewing of fantastical films. Media Psychology, 15, 327-355.

NOTE: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Brian C. Britt (ORCID: 0000-0002-1521-3258) received his PhD from Purdue University in 2013. He is currently an assistant professor in the Department of Advertising and Public Relations and the Associate Director of Data Analytics in the Public Opinion Lab at the University of Alabama. His research interests include the study of large-scale online organizations and the development of computational social scientific research methods. He is available at bcbritt@ua.edu.

Rebecca K. Britt (ORCID: 0000-0002-4595-4604) received her Ph.D. from Purdue University in 2012. She is currently an associate professor in the Department of Journalism and Creative Media at the University of Alabama. Her research interests include health communication campaigns, media effects, data scraping, online communities and subcultures, and games and their health uses. She is available at rkbritt@ua.edu.

Manuscript received 30 September 2020, revised 16 November 2020; accepted 20 November 2020.

APPENDIX A

Narrative Believability Scale (NBS-12)

Plausibility

- I believe this story could be true.

- This story was plausible.

- This story seems to be true.

Completeness

- It was easy to follow the story from beginning to end.

- It was hard to follow this story. (R)

- If I were writing this story, I would have organized it differently. (R)

Consistency